Double battle near Vyazma and Bryansk

| date | September 30th to October 30th, 1941 |

|---|---|

| place | Vyazma and Bryansk , Soviet Union near Moscow |

| output | German victory |

| consequences | Slowdown of the German advance |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| 46 infantry divisions 1 cavalry division 14 armored divisions 8 motorized infantry divisions 6 security divisions 1 SS cavalry brigade Total: 1,929,406 soldiers * |

84 rifle divisions 1 rifle brigade 9 cavalry divisions 3 motorized divisions 13 tank brigades Total: 1,250,000 soldiers |

| losses | |

|

unknown |

67 rifle divisions |

1941: Białystok-Minsk - Dubno-Lutsk-Rivne - Smolensk - Uman - Kiev - Odessa - Leningrad blockade - Vyazma-Bryansk - Kharkov - Rostov - Moscow - Tula

1942: Rzhev - Kharkiv - Company Blue - companies Braunschweig - company Edelweiss - Stalingrad - Operation Mars

1943: Voronezh-Kharkov - Operation Iskra - North Caucasus - Kharkov - Citadel Company - Oryol - Donets-Mius - Donbass - Belgorod-Kharkov - Smolensk - Dnepr

1944: Dnepr-Carpathians - Leningrad-Novgorod - Crimea - Vyborg-Petrozavodsk - Operation Bagration - Lviv-Sandomierz - Jassy-Kishinew - Belgrade - Petsamo-Kirkenes - Baltic States - Carpathians - Hungary

1945: Courland - Vistula-Oder - East Prussia - West Carpathians - Lower Silesia - East Pomerania - Lake Balaton - Upper Silesia - Vienna - Oder - Berlin - Prague

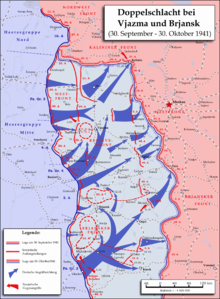

The double battle of Vyazma and Bryansk was a military conflict on the German-Soviet front during World War II . It began under the code name company Taifun on September 30, 1941 with the attack of the German Army Group Center against the Soviet West , Reserve and Brjansk Front . The aim of the German offensive was smashing the organizations of the Red Army before Moscow and then the conquest of the city itself. Despite initial successes of the Wehrmacht , which at Vyazma and Bryansk large parts of the Soviet defenders encircle could, and consume, the advance ran until 30 October 1941 stuck in the autumnal mud and the increasing Soviet resistance. Only after more than two weeks was it able to go back to the offensive with the onset of frosty weather and thus open the battle for Moscow .

background

Since the start of the attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the three German army groups had broken through the defense of the Red Army and wiped out numerous Soviet units in several kettle battles . The Army Group Center was in the general direction Moscow recognized. They had won the battles of Minsk and Smolensk , but on July 30, 1941, they received the order to temporarily stop the advance.

In the days before, there had been a crisis in the German leadership over the question of how the further operations should be designed. Hitler was of the opinion that the conquest of Moscow was not a priority. In his opinion, the economically important areas of Ukraine had to be occupied first and Leningrad had to be conquered. That is why Army Group Center was to hand over its armored forces to the neighboring Army Groups North and South , in whose area of operations these objectives were located. For the advance on Moscow, however, only the weakened infantry armies would have been left, which were not up to the task in view of the ongoing Soviet counter-attacks. The military leadership in the High Command of the Army (OKH) considered this decision to be wrong and tried to dissuade Hitler from it. The Chief of the General Staff of the Army, Colonel-General Franz Halder , pointed to the danger that if the enemy were not to proceed to Moscow, the enemy would gain time and a later German offensive could stop at the onset of winter, which would not achieve the military goal of Operation Barbarossa . Nevertheless, on July 28, Hitler got his ideas through by having the 2nd Army and Panzer Group 2 turn south into the Ukraine, where they took part in the Battle of Kiev . The 3rd Panzer Group was moved to the north to take part in the conquest of Leningrad.

It was only after some “persuasion” that the OKH and the Wehrmacht command staff were able to prevail in mid-August. In Directive No. 34 on August 12, Hitler stipulated that the “State, Armaments and Transport Center” Moscow should be occupied before winter set in. However, the goals of Leningrad and Ukraine still had priority, so that the fighting there should first be concluded before an offensive on Moscow could be prepared. The fighting in the Ukraine and in front of Leningrad dragged on until September. Even before its final conclusion, however, Hitler issued directive No. 35 on September 6, 1941, which formed the basis of the future offensive:

“The initial successes against the enemy forces located between the inner wings of Army Groups South and Central [...] created the basis for an operation seeking a decision against the Army Group Tymoshenko, which was in offensive fighting in front of the Army Group. It must be crushed in the limited time available until the onset of winter weather. It is important to summarize all forces of the army and the air force that are dispensable on the wings and can be brought in on time. "

The company's aim was to “destroy the enemy located in the east of Smolensk with a double embrace in the general direction of Vyazma [...]. […] Only then […] will Army Group Center set up pursuit in the direction of Moscow - leaning against the Oka on the right, leaning against the Upper Volga on the left. ” With that Hitler was back on the rough lines of OKH and the High Command of Army Group Center swiveled in.

German preparations for attack

Even before the decision to turn off the tank units against Kiev on August 18, 1941, the German General Staff had submitted an operation plan that provided for the Soviet units in front of Army Group Center . In this planning it was initially left open whether after a successful advance the encirclement of Moscow should be carried out directly or whether the Soviet units should first be enclosed and wiped out in front of the capital. In a discussion between Hitler and the Army Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch on August 30, 1941, they had already agreed on a new advance towards Moscow. The commanders of the armies concerned were informed of this even before Hitler's official instructions. A few days later, directive No. 35 was issued from Hitler's headquarters.

The Army High Command (OKH) issued on 10 September 1941, a referral for future operations , the Chief of Staff Franz Halder instructed Hitler clarified and partly reinterpreted. Hitler's plan provided for Moscow to be captured only after the Soviet armed forces had been annihilated, while Halder ordered units to advance to the capital at the same time . He also included the 2nd Army and Panzer Group 2 , which at that time were still bound in front of Kiev, in the planning. These should compete against Oryol from the Romny area . With this, Halder had also created a third strike group for the attack to the east. The instruction also provided for the surrender of troops from the other army groups. The Army Group South had two General Command, give four infantry divisions, two armored divisions and two motorized infantry divisions, while in the Army Group North with the Panzer Group 4 were three General Command, five armored divisions and two motorized infantry divisions.

While Hitler wanted to set the armored arm of the armored troops directly on Vyazma, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock , the commander in chief of Army Group Center , wanted to encircle the enemy far beyond Vyazma near Gschatsk . Colonel-General Halder agreed and assured von Bock of his support. On September 17, 1941, the two of them discussed the specific operational plans drawn up by Bock. On September 24th, the commanders-in-chief of the armies, tank groups and Luftflotte 2 met with von Bock and Halder in Smolensk for a final meeting of the enterprise, which on September 19th had been named Operation Taifun . It stipulated that Panzer Group 2 should start the attack on September 30, two days before the other units. Colonel-General Heinz Guderian had achieved this; Since there were hardly any solid roads in his attack area, he was of the opinion that solid roads at Oryol and from there cross connections to Bryansk should be gained as quickly as possible.

The final orders to the individual armies were given on September 26th. To ensure close cooperation between tank groups and infantry armies, Panzer Group 4 was operationally subordinate to the 4th Army . It was supposed to attack along the Roslavl – Moscow road and, after a successful breakthrough on both sides of Vyazma, swivel towards the Smolensk – Moscow motorway. To the north of this, Panzer Group 3 , which was subordinate to the 9th Army , had to break through the Soviet lines south of Bely and win the Vyazma – Rzhev road before turning west of Vyazma. The inner wings of both groups should meanwhile bind the enemy before them. The 2nd Army was given the task of advancing against Sukhinichi and Meshchovsk to protect the flank of the 9th Army . Finally, Panzer Group 2, which was directly under the command of Army Group Center , was supposed to roll up the Soviet positions from the south. In cooperation with the 2nd Army, the enemy in the Bryansk area was to be wiped out. The start of the attack (except for Panzer Group 2) was to be on October 2, 1941 at 5:30 a.m.

On September 6, Hitler had asked Halder that the operation should begin within eight to ten days, which Halder described as impossible given the condition of the troops. Panzer Group 2 and the 2nd Army first had to be detached from the containment ring of the Kiev pocket, and the units had lost their offensive power in the long defensive battles off Smolensk. The relocation of units from the other army groups over a distance of more than 600 km and the approach of the 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions from Germany took a lot of time. In addition, it was no longer possible to compensate for the personnel losses of the previous months. Nevertheless, on October 2, 1941, Army Group Center was able to manage a total of 1,929,406 soldiers in 78 divisions (46 Infantry Division, 1 Cavalry Division, 14 Pz.Div., 8 Infantry Division (motorized), 6 Sich. Div., 1 SS-Kav.Brig.), Which, however, did not all take part in the planned offensive. However, these formations had lost a considerable amount of their combat strength, as both the soldiers and the material had been in action without interruption for months.

In addition, Hitler held back large quantities of tanks that he had earmarked for use after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since the permanent failures were therefore not replaced, the tank population of Panzer Group 2 was only 50 percent at the start of operations, that of Panzer Group 3 was 70 to 80 percent and only that of Panzer Group 4 was slightly below 100 percent. Of these stocks, however, hardly all vehicles were operational. There was also a deficit of 22 percent in motor vehicles and 30 percent in tractors. Only 125 tanks were promised as replacements, although Colonel General Halder asked in vain for another 181 tanks to be released. But even if they had been added, the operational readiness of the particularly weakened tank divisions would only have increased by 10 percent. The assertion in Soviet historiography that the German attack formations were fully replenished and equipped with 1700 tanks at their disposal does not correspond to the facts. The historian Klaus Reinhardt determined the actual number of 1220 tanks.

In Gomel , Roslavl, Smolensk and Vitebsk , storage warehouses were set up to supply the troops during the planned offensive. However, 27 supply trains per day would have been necessary to replenish the camps in September, and even 29 in October. However, the actual output only amounted to these numbers in the first 13 days. At the end of September and October, only 22 trains a day were arriving before the number dropped further to 20 in November. The supply was therefore only considered “satisfactory” .

Soviet situation

Shortly after the fighting for Smolensk, the Soviet State Defense Committee (GKO) ordered the expansion of defense positions in front of Moscow. Since July 16, 1941, a fortified defense line has been built in the Moshaisk area with the help of civilians. Around 85,000–100,000 Muscovites, mostly women, are said to have participated in the work. By the beginning of the German offensive, the various defensive structures ( bunkers , anti-tank trenches, trenches) were only 40 to 80 percent complete.

On September 12, 1941, Colonel General IS Konev took command of the Western Front . At that time, this comprised the 22nd, 29th, 30th, 19th, 16th and 20th armies, which stood side by side from Lake Selig in the north to Jelnja in the south. In addition, there was still the reserve front of Marshal of the Soviet Union S. M. Budjonny , whose 24th and 43rd armies stood along the Desna and thus connected to the left of the western front , but which with their main mass (31st, 49th, 32nd and 33rd Army) also formed a second line of defense in the Vyazma area 35 km behind the front. Farther to the south, the 50th , 3rd and 13th Armies of the Brjansk Front under Colonel-General AI Jerjomenko stood in the area between Zhukovka and Vorozhba . These fronts comprised about 40 percent of the personnel and artillery and 35 percent of the tanks and planes of all Soviet armed forces.

After the huge losses that the Red Army suffered in the summer of 1941, it now lacked trained staff officers . In addition, there was no telecommunication device , so that the connection between the individual bars was poor and prone to interference. Sometimes the front line was too thin. The six armies of the Western Front defended a stretch of 340 km, with each army having 5-6 rifle divisions in the first line and only one in reserve. The associations only partly consisted of trained veterans, who had been supplemented with practically untrained volunteers. Because of their hasty mobilization, they lacked machine guns and other infantry weapons . Allegedly only 6 to 9 guns were available per kilometer at the front. The Red Army was also unable to compensate for the losses of tanks in the numerous battles of the previous months. Colonel-General Konew had 479 tanks, but only 45 of these were of a modern type. In the official Soviet representation the number of 770 tanks on the entire western section of the front was later given. However, there is no reliable information about the size of the Soviet armed forces on the three fronts . In various Soviet publications they range from 800,000 soldiers, 6,800 guns, 780 tanks and 360-527 aircraft to a maximum of 1,250,000 soldiers, 10,598 guns, 990 tanks and 930 aircraft. According to the information from the Russian historian GF Kriwoschejew from 2001, based on archive material, the higher numbers can be assumed.

| front | Rifle divisions | Rifle brigades | Cavalry divisions | Motorized divisions | Tank brigades | Workforce |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colonel-General Konew pointed out to the Stawka on September 26th that the Germans were preparing to attack, which suggested an offensive for October 1st. However, he expected only a relatively limited advance in the area of the 19th, 16th and 20th Armies. In its directive of September 27th, the Stawka only reacted with general instructions. They ordered the expansion of the defensive positions to be accelerated. The commanders at the front were instructed to relieve weakened divisions and relocate them behind the front to freshen up. In this way reserves should be created. The front troops themselves were placed on heightened alert. However, the individual army commanders were not adequately informed. Gen. Lt. KK Rokossowski , at that time in command of the 16th Army, later wrote in his memoir: “The information provided by the army commanders in chief was generally poorly organized at that time. Practically we knew nothing of what was happening inside, let alone outside the front, which severely hindered our work. ” It was not until September 28 that the Brjansk Front was also warned of imminent attacks. Colonel-General Yeryomenko proposed a regrouping of the troops because of this. However, this did not happen because the German attack began two days later. In the area of the western front , Lieutenant General Konev forbade any form of evasion. The troops were supposed to defend every meter of the ground. In order to be prepared for possible breakthroughs by the enemy, he assembled an operational reserve near Wadino north of Dorogobusch under his deputy Lieutenant General IW Boldin .

At the express orders of Stalin, the commanders at the front continued to undertake limited offensive operations, which weakened the defenses of the troops and cost them great losses even before the German attack began. For example, the 43rd Army under Major General PP Sobennikov carried out an advance near Roslavl , while on September 29th Major General AN Yermakov received the order to retake the city of Glukhov with his operational group . In both cases the Soviets pushed straight into the deployment zones of the German troops and suffered heavy losses. In the days that followed, this made it easier for German troops to break through the Soviet lines.

course

Bryansk Cauldron

On September 30th, under the best weather conditions, Panzer Group 2 under Colonel General Guderian began its attack east of Gluchow against the Brjansk Front . By around 1 p.m. on October 1, the XXIV Motorized Army Corps (AK (mot.)) Had broken through the left wing of the Yermakov group and advanced on Sevsk , while the XXXXVII. AK (motorized) advanced on Karachev . That night, Stalin and Chief of Staff BM Shaposhnikov ordered the broken-in German units to be cut off by flank attacks by the 13th Army (Gen. Maj. Gorodnyansky) and the Yermakov group . These isolated counter-attacks by individual tank brigades hit the German XXXXVIII deployed in the flank . motorized army corps , the advance of which was also slowed down, but the situation was quickly restored through the deployment of the 9th Panzer Division . On October 3rd, German advance formations of the 4th Panzer Division were able to manage the strategically important, but due to failures of the local commander Gen.Lt. AA Tyurin taking undefended Oryol.

The German 2nd Army under Colonel-General Maximilian von Weichs took up action against the right wing of the Brjansker Front on October 2nd , where it encountered bitter resistance from the Soviet 3rd (Gen. Maj. JG Kreiser ) and 50th Armies (Gen. Maj . MP Petrov ). It was only with the breakthrough of Panzer Group 4 through the positions of the Soviet 43rd Army (Gen. Lt. Stepan Akimow) further to the north that the 2nd Army managed to bypass the Soviet front through the gap. By October 5, she finally took Shisdra . Almost simultaneously, the advance of XXXXVII took place from the south. AK (motorized) via Karachev on Brjansk, which was captured on October 6th with its important Desna bridges. This cut off the supply and communication lines of the Brjansk Front .

There was great confusion on the Soviet side these days. The first German air raids interrupted the connection between the front staff and the subordinate armies. The operational reserve group at Bryansk could not be used because it was soon attacked by German troops itself. Gen. Lt. Yeryomenko soon realized the danger that threatened his troops. He therefore asked Chief of Staff Shaposhnikov in Moscow for permission to switch to a flexible defense with alternative options. This was refused and Yeryomenko was ordered to defend every meter of the ground. On October 5, the commander of the Brjansk Front reported that he was forced to evade eastwards immediately. However, by the morning of October 6th, he received no response. At noon, German tanks appeared near his command post, so that he had to flee with three tanks and a few infantrymen. This meant that there was no longer any uniform leadership on the Soviet side. The Stawka was later unable to transmit the order to withdraw. Assuming that Yeryomenko had fallen, she instructed the commander of the 50th Army, Gen. Maj. MP Petrov with the leadership of the front.

By October 9, another advance by the 167th Inf. Div. (2nd Army) to a union with the 17th Pz.Div. (2nd Panzer Army) near Brjansk, which closed the ring around the Soviet 3rd and 13th Army , which was located southwest of Trubchevsk . On the same day Gfm ordered. von Bock that the removal of this cauldron would be entrusted to the 2nd Panzer Army. The 2nd Army should take care of the destruction of the enemy to the north. In fact, they advanced further, and on October 12, another pocket around the Soviet 50th Army was closed at Bujanowitschi . However, since both the 2nd Panzer and 2nd Armies, on the orders of the OKH and the Commander-in-Chief of Army Group Center, had to advance with large parts to the east without having "cleared" the cauldrons beforehand, only a few stood to enclose the enemy Forces available.

On October 12, 13 and 14, the Soviet armies broke out. The 3rd Army managed to break out on the Navlja, the 13th Army at Khomutowka . The 50th Army, however, failed with heavy losses at the Resseta. The last Soviet groups only succeeded on 22/23. October an outbreak in the direction of Belyov . In line Beljow- Fatezh Eremenko collected the re between 17 and 24 October Bryansk Front . However, the troops had suffered enormous losses. The 13th Army had lost all of its artillery and rear service when it breached. In addition, the combat strength of their seven rifle divisions was only 1,500-2,000 men. The five rifle divisions of 3rd Army had an average combat strength of only 2,000 men. The 50th Army, however, was still able to save some material. Gen. Lt. Yeryomenko was wounded on October 12 and then flown out. Gen. Maj. Petrov died of gangrene during the fighting . German reports speak of 108,000 Soviet prisoners alone, along with 257 tanks and 763 guns that had been destroyed or captured. On the other hand, Gen. Lt. Jerjomenko later in his memoirs that the 3rd Soviet Army alone suffered losses of 5,500 dead and wounded, as well as 100 prisoners and 250 motor vehicles. and taught 50 tanks.

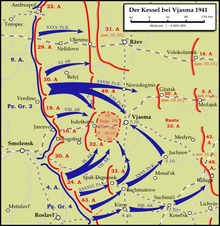

Vyazma Cauldron

On October 2, Panzer Groups 3 and 4 and the 4th and 9th Armies also went on the offensive. The attack by Panzer Group 4 of Colonel General Erich Hoepner broke through the Soviet defense lines of the 43rd Army ( Gen. Maj . PP Sobennikow ) on the Desna at 5.30 a.m. The XXXX. AK (motorized) pushed into the rear area and was able to take Kirov and Mosalsk with the 10th Panzer Division on October 4th , which was 110 km from the starting position. Juchnow fell the next day . In Moscow the Stavka initially remained without news from the front. When the aviation forces of the 120th Fighter Regiment reported the action of motorized columns on Juchnow, their news was not believed. The head of the Moscow Aviation Forces, Colonel Sbytov, was even accused by the head of the NKVD Lavrenti Beria of "spreading fear-mongering ". The break-in of Panzer Group 4 was in the area of Marshal Budjonny's Soviet reserve front. After using his few reserves early on, he reported to the Stawka on October 5th: “The situation on the left wing of the reserve front is extremely serious. There are no forces available to block the […] resulting break-in. [...] The forces of the front are not sufficient to stop the attack of the enemy [...]. " Gen.Ost. Hoepner was therefore able to operate relatively freely and initially shot the XXXX. Motorized AK (motorized) headed northwest towards Vyazma to meet the troops of Panzer Group 3 here. On the left wing of it went the XXXXVI. AK (mot.) Against stronger Soviet resistance. It took Spas-Demensk on October 4th and was ordered by the Commander of the 4th Army, Gfm. Günther von Kluge , then turned to the north to form the southern part of the planned boiler. The LVI was responsible for securing operations to the east. AK (motorized).

The advance of Panzer Group 3 under Colonel General Hermann Hoth turned out to be more difficult. Although it broke through the Soviet positions at the seam of the 19th (Gen. Lt. Lukin ) and 30th Armies (Gen. Maj. Chomenko) and on October 3rd built a bridgehead over the Dnieper , Colonel General Konev then brought his operational here Group under IW Boldin (3 Pz.Brig .; 1 Rifle Division (motorized); 1 Rifle Division) deployed to seal off the German breakthrough. On the 3rd / 4th In October she attacked Cholm-Zhirkovsky. The place changed hands several times, but in the end Gen.Lt. Boldin's troops withdraw. According to Soviet information, 59 German tanks are said to have been destroyed. Now, however, there were supply bottlenecks in the fuel supply for Panzer Group 3, which brought the advance of the Panzer divisions to a standstill. Operational readiness was only restored on the afternoon of October 5th after the aircraft had been brought in by Air Fleet 2 . Meanwhile, the 4th and 9th Armies advanced behind the armored groups in order to relieve them later on the boiler front. At the same time, however, they also attacked the Soviet positions head-on from the west in order to narrow the cavity that was forming.

After the counterattacks had failed, Colonel General Konev applied on October 4th to withdraw his front into the Gschatsk- Vyazma line. But it was not until the afternoon of October 5th that the Stawka made a decision. Konev was allowed to go back to the Rzhev- Vyazma line . At the same time she placed the 31st and 32nd Armies of the Reserve Front under him in order to unify the command in the Vyazma area. But even these two formations, which had been set back a long way, were already involved in combat, so that they turned out to be a real reinforcement of the western front . A similar withdrawal order also reached the reserve front . A slow and disorderly retreat of the Soviet units began. The cover of the retreat was given to the Boldin group and the 31st Army, while the 22nd and 29th Armies fell to Rzhev and Staritsa , and the 49th and 43rd Armies to Kaluga and Medyn . As the connection to the Boldin group and the 31st Army was soon lost, the command of the retreat and its cover was given to the 32nd Army of Gen. Maj. Wischnewski transferred. By October 7, at 10:30 a.m., Vyazma fell into the hands of XXXX. AK (motorized) of Panzer Group 4 and the LVI met there in the course of the morning . AK (motorized) of Panzer Group 3. That closed the kettle.

In addition to the Boldin group, the Soviet 19th Army (Gen. Lt. Lukin ), 24th Army ( Gen. Maj . Rakutin ), 32nd Army ( Gen. Maj . Wischnewski) and the 20th Army (Gen .Lt. Yershakov). However, the troops of the 16th Army (Gen. Lt. Rokossowski ) had also been transferred to the last one , so that a total of more than five armies were encircled. Gen. Lt. MF Lukin took over the supreme command of the enclosed units. He only received instructions from the new commander of the Western Front Army General G.K. on October 10 and 12. Zhukov with orders to break through to the east. However, these radio messages went unanswered. In the first few days, attempts to break out were directed against XXXX, which is in front of Vyasma. and XXXXVI. AK (motorized). When this was unsuccessful, Gen. Lt. Lukin launched the attacks in the more confusing area in the south, where the heaviest attack occurred on the night of 10/11. October against the German 11th Panzer Division took place. At least two divisions managed to break out of the encirclement. From October 12th these attempts to escape subsided and in the following days only small groups managed to make their way to the Soviet lines. On October 14, before the boiler was “cleared out”, Panzer Group 4 alone reported 140,000 prisoners as well as 154 tanks and 933 artillery pieces in their area that could be captured or destroyed. Gen. Lt. Lukin had the guns and vehicles blown up in the days that followed before the bulk of his troops went into German captivity by October 20, 1941.

Reorganization of the Soviet defense

On October 6th, the State Defense Commission (GKO) met for an emergency meeting in view of the looming disruption of three fronts and the threat to the capital. The commission determined the at least partially developed position at Moshaisk to be the new line of defense and instructed the Stawka to bring it into a state of defense as soon as possible. First, four rifle divisions of the Western Front were ordered there to organize a makeshift defense. At the same time all receding units and all available reserves were thrown into this position. On October 10th, in addition to the four rifle divisions, three rifle regiments, five machine gun battalions and the years from different military schools had gathered there. Further newly established five machine-gun battalions, five tank brigades and ten anti-tank regiments (each of which had only battalion strength) were on the march. By mid-October, 11 rifle divisions, 16 tank brigades, 40 artillery regiments, all in all around 90,000 men, had gathered near Moshaisk. Gradually, further reinforcements from other sections of the front as well as Siberian rifle divisions arrived in the Moscow area. The Stawka organized two new armies from these associations. In the Wolokolamsk area , a 16th Army was again formed under Gen. Lt. Rokossovsky and at Moshaisk took over Gen. Maj. DD Lelyushenko in command of the 5th Army. However, after Leljuschenko was wounded, Gen. Maj. LA Goworow Army Commander. The troops of the 1st Guards Rifle Corps standing near Mtsensk formed the basis for the formation of the 26th Army under General AW Kurkin . Parts of the 33rd Army (Gen. Lt. MG Yefremov ) and parts of the 43rd Army (Gen. Golubew) at Malojaroslavz and parts of the 49th Army (Gen. IG Sacharkin .) At Kaluga were also able to join the new line of defense at Naro-Fominsk ) withdraw. After their outbreak, the remnants of the 3rd, 13th and 50th Armies (commanded by Gen. Maj. Ermakov after Petrov's death) of the Brjansk Front were reintegrated into the front line.

In a second step, the GKO tried to create order in the chaos of the military leadership. First, the troops gathered at Moshaisk were on October 9th as the front of the Moshaisk Defense Line under Gen. Lt. PA Artemjew (Chief of the Moscow Defense District) summarized. At the same time, a commission from the GKO, consisting of Molotov , Mikoyan , Malenkov , Voroshilov and Vasilevsky , went to the front to act on behalf of the headquarters. Independently of this, Stalin also summoned the former chief of staff and previous commander of the Leningrad Front , Army General GK Zhukov , to Moscow to inspect and assess the critical areas of the front for him. These representatives found chaos at the front. So nobody on the staff of the reserve front knew where their commander was. In Medyn , an access point to Moscow, no defense was organized except for three soldiers. The three fronts had no contact with one another and often lost contact with their armies. The Stawka responded by reorganizing the top leadership. On October 9, Army General Zhukov took command of the Western Front . On the following day the troops of the reserve front and on October 12 the units of the front of the Moshaisk defense line were subordinated to this. This meant that the defense troops were under a single command. On October 17, there was another change in that the Soviet 22nd, 29th and 30th Army in the Kalinin area were combined to form a new Kalinin Front and placed under Colonel General Konev in order to unify the leadership in this sector.

Since his troops were numerically weak and battered, Army General Zhukov tried to stabilize the front by all means. In his order no. 0345 of October 13, 1941, he demanded the full commitment of all soldiers and announced: “Cowards and alarmists who leave the battlefield, who abandon the positions they have taken without authorization, who throw away their weapons and equipment to shoot on the spot. ” In order to make up for the loss of motor vehicles, he also had all available vehicles in the Moscow area requisitioned. The beginning of the mud period also favored the Soviet defense. Zhukov quickly realized that the Wehrmacht units could only proceed on the solid roads. He therefore concentrated the few available units on the few fixed access roads to Moscow near Volokolamsk, Istra , Moshaisk, Maloyaroslavz, Podolsk and Kaluga . The severely decimated units of the Brjansk Front did the same, mainly defending the Oryol- Tula road . At the same time, the Commander of the Rear Services of the Red Army, General AW Chrulew, ordered supply units to be set up with Panjewagen , as the mud also brought the Soviet supplies to a standstill and supply aircraft were not available in sufficient numbers. This measure helped to overcome the supply crises on the Soviet side.

German pursuit operations

While the fighting over the Kessel was still in progress, the German troops began to exploit the loopholes they had cut in the Soviet lines. This corresponded to the plans of the OKH and the Commander in Chief of Army Group Center . So had Gfm. Bock of Panzer Group 2 immediately after taking Orjols on October 4, the command "in the possession of the Mtsensk District ... to put" and proceed as far as possible in the direction of Tula. However, the Stawka had meanwhile taken measures to prevent a German breakthrough via Tula in the direction of Moscow. They moved 5,500 soldiers to Mtsensk by air. Other reserves also arrived there. When the 5th and 6th Guards Rifle Divisions, the 4th and 11th Panzer Brigades, the 5th Airborne Corps, the 36th Motorcyclist Regiment and a workers' regiment from Tula were gathered around Mtsensk, these units were grouped under the 1st Guards Rifle Corps the order of Gen.Lt. DD Leljuschenko (who a few days later took over the 5th Army) together. When the 4th Panzer Division arrived in front of Mtsensk on October 6, it was ambushed by the 4th Panzer Brigade (Colonel Michail Katukow ), which was equipped with superior T-34s . The 4th Panzer Division suffered heavy losses and had to retreat. It was not until October 12 that she was finally able to take Mtsensk, but without being able to proceed. The boiler fighting itself also held up the German advance. According to an army group order of October 4th, the pockets were only to be cleared by part of Panzer Group 2, but it soon became apparent that the 2nd Army was also necessary for this. Attempts to break out by the Brjansk Front initially prevented the German persecution forces from being strengthened in the days that followed.

At Vyazma it was a matter of releasing Panzer Groups 3 and 4, which had closed the pocket on October 7, by the infantry forces of the 4th and 9th Armies, thus freeing them for a further advance towards Moscow. But these armies made slow progress due to stubborn Soviet resistance. After the cauldron was closed, OKH and the High Command of Army Group Center were of the opinion that the enemy no longer had any essential forces to defend Moscow. Colonel General Halder and Gfm met on October 7th. von Bock at the headquarters of the Army Group. It was decided immediately to take advantage of the hour. Gfm. von Bock was convinced that he was strong enough to clear out the cauldrons and to advance to Moscow at the same time . The only difference was the direction of the persecution. The OKH was convinced that the enemy was so weak that it was sufficient to pursue him with only part of the forces in the direction of Moscow. Hitler demanded the capture of Kursk by the 2nd Panzer Army. In addition, Panzer Group 3 and parts of the 9th Army were to be branched off to the north in order to smash the Soviet forces in the Ostashkov area in cooperation with Army Group North . Gfm. von Bock did not agree to this fragmentation of his forces, but the following day a Fuehrer order determined that Panzer Group 3 should be turned off as soon as the tank battles allowed. The XXXXI. AK (mot.) Therefore attacked Kalinin a short time later. Panzer Group 4 stayed with its XXXVI. and XXXX. AK (mot.) Tied to the front of the Vyazma pocket until mid-October. So in the end only the LVII was left. AK (motorized) (19th and 20th Panzer Division, 3rd Inf.Div. (Motorized)) and the XII. and XIII. AK available for tracking to Moscow.

On October 11th, the German persecuting forces were able to take Medyn and the following day Kaluga, with which they had already broken into the line of defense at Moshaisk. They were able to use these successes to take Tarussa and bypass Malojaroslavets. After that there was heavy fighting between the LVII in the Borovsk area . AK (motorized) and the Soviet 110th Motorized Rifle Division and 151st Motorized Rifle Brigade, which lasted until October 16. The Germans are said to have lost 20 tanks in the process alone before the Soviets had to resort to Naro-Fominsk. After Malojaroslawez had also fallen, the 43rd Soviet Army had to retreat behind the Nara on October 18. To the north of it, after six days of fighting and the loss of allegedly 60 tanks, Moshaisk himself fell to the German troops.

Although Kalinin had also fallen on October 14th, the German forces hardly managed to counter the stiffening resistance of the Soviet units, as not enough persecution forces could yet be freed on the German side due to the ongoing tank fighting. These could only start the persecution in bulk from October 15th. But by then, the armored units in particular had suffered severe losses. The 6th Pz.Div. had only 60 tanks left, the 20th Pz.Div. had lost 43 of their 283 tanks. The 4th Pz.Div. After the heavy fighting against the 1st Guards Rifle Corps off Mtsensk, it only had 38 tanks. The Army Group Center had lost during the period from the start of operations until 17 October 47,430 soldiers and 1,791 officers. In their pursuit, the weakened associations also encountered a motivated opponent in expanded positions. Quite a few units reported the "hardest fighting since the beginning of the Eastern campaign" (war diary of the LVII. AK (mot.)). Soon the bad weather conditions should also hamper German operations.

The offensive stalled

On 6./7. October saw the first snow fall in the area of the 2nd Panzer Army, which quickly silted up the roads. The next night, heavy autumn rains fell over the entire area of Army Group Mid . This ushered in the time of the Russian Rasputiza (Russian for "no road"), which in the following period severely hampered German operations. In the headquarters of Army Group Center , it was already recorded on October 9th: “A move of the armored units away from the main roads is due to groundless and bad roads due to the bad weather. Currently not possible. As a result, there were also problems with operating supplies. ” The Rasputiza did not have a noticeable effect on the combat management until October 13th, as the supply of fuel and ammunition could no longer be ensured from this point on.

From the middle of October the 2nd Panzer Army made no progress and the pursuit units of the 2nd Army were also in place. The Panzer Army reported on October 12th that their motorized units were only advancing 1 km an hour. An orderly supply was soon no longer possible. This condition, as noted by the headquarters of the 2nd Army on October 18, would last as long as "as long as the supply is not rebuilt" . The 4th Army made no further progress either, as it was itself harassed by constant Soviet counter-attacks. It suspended its right wing action on October 16. In the area of 9th Army and Panzer Group 3, the units were dependent on the Vyazma-Moscow motorway, but this route in particular was severely damaged by numerous explosions, bomb damage and overcrowding. Finally, on October 19, the entire 5th Infantry Division had to be called in for repair work on the motorway. In addition, Panzer Group 3 was forced into defense by counter-attacks by the Kalininer Front . The units of Luftflotte 2 were also less and less able to intervene in the fighting due to the bad weather. Gfm. von Bock noted after on 19./20. October practically all attack movements had to be stopped, on October 25th in his diary:

“The tearing apart of the Army Group in connection with the terrible weather resulted in us being stuck. This gives the Russian time to replenish his battered divisions and strengthen the defense [...] This is very bad. "

The only land gains could still be made in the area of the Brjansk Front , and this only because its right flank was no longer covered by the German successes against the Western Front . In order to close the almost 60 km wide gap, the Stawka therefore ordered on October 24th to withdraw the armies of the Brjansk Front into the line Dubna-Plawsk-Verkhovye-Livny-Kastornoje. This withdrawal began on October 26 and was largely complete four days later. When the 2nd Panzer Army took up the chase and tried to take the city of Tula on October 29, it encountered strong Soviet resistance from the 50th Army. From this a few more battles developed, especially on the flank of the tank army, which lasted until November 7th, but were unsuccessful.

In view of the hopeless situation, Gfm. von Bock issued the order on November 1, 1941, “that for the time being no further action will be taken, but that everything will be prepared for the attack and supply problems will be resolved as quickly as possible so that if the weather is good (frost) can be started immediately. “ This practically ended the German“ company Taifun ”.

Consequences of the battle

Although Hitler and the Wehrmacht command staff as well as the OKH general staff fell into an optimistic mood after the initial successes in the "Operation Taifun" and were already drafting plans for further operations with far-reaching goals beyond Moscow, the offensive had stalled at the end of October 1941. On October 12, Hitler had also issued orders to treat Moscow, which was to be locked up and then shelled and whose surrender, even if offered, could not be accepted. Instead, the German advance had come to a standstill about 80 km from the Soviet capital. Neither the primary aim of annihilating the bulk of the opposing armed forces nor the secondary aim of taking Moscow had been achieved.

However, the Red Army had suffered great losses. In the absence of precise Soviet information, one has to rely on German sources such as the Wehrmacht report, which, after the end of the fighting around the Kessel, reported the destruction of 67 Soviet rifle, 6 cavalry and 7 tank divisions with 1,242 tanks and 5,412 artillery and the capture of 663,000 Red Army soldiers reported. Since, according to Soviet information, fewer than 100,000 soldiers were available to protect Moscow in mid-October, this representation is plausible.

In Moscow itself, the events led to a crisis. On October 13, the chairman of the Moscow City Committee, AS Shcherbakov, publicly announced that the capital was under threat. In the course of this, thousands of Muscovites were called in to expand the defenses around the city and 25 workers battalions of 12,000 volunteers were set up to occupy these positions from October 17th. Nevertheless, on October 16, Stalin decided to evacuate the city, so that most of the government, party and military organizations began to move to Kuibyshev . Industrial companies were also evacuated. Panic then broke out in the capital, which was not slowed down by the fact that Stalin decided to stay in Moscow. Many residents fled and food, which had become scarce, was looted. Therefore, on October 19, the state of siege was declared and martial law was imposed.

In the first two weeks of November, which were marked by an extensive standstill in operations, both sides replenished their weakened bandages. Neither side was able to completely compensate for their previous losses, especially not the Wehrmacht, with its long supply routes. While a number of German front commanders spoke out in favor of going over to the defense and choosing a favorable position for the winter months, the OKH was of the opinion that only one last "effort" was needed to achieve the goal of the campaign against the Soviet Union still to be achieved. After the onset of the period of frost, in which the roads became more passable, the decision was made to renew the attack during a meeting of the highest military commanders in Orsha on November 13th. On November 17, 1941, the battle for Moscow began with the new German offensive . In this attempt, too, the Wehrmacht should not have a resounding success. On December 5th, the Red Army and its reserves went over to the counteroffensive and by the spring of 1942 was able to regain large parts of the area that had been lost in the autumn.

Evaluation and reception

Measured by the size of the casualties, the battles at Vyazma and Bryansk were one of the greatest military defeats of the Soviet Union during the Second World War. In Russian historiography it is almost always reckoned with the "Battle for Moscow" (Битва за Москву), which ultimately ended with a Soviet success. Occasionally, attempts were made to find the causes of this first setback. In addition to emphasizing the numerical superiority of the Wehrmacht units, some commanders such as IS Konew or KK Rokossowski pointed out in their memoirs that the High Command in Moscow had made serious omissions. Marshal Wassilewski particularly criticized the confused command structure:

“The failure at Vyazma can be explained not only by the superiority of the enemy and the lack of reserves, but also by the fact that the General Staff and Headquarters had wrongly determined the main thrust of the enemy and consequently also wrongly built up the defense. [...] The operational structure was extremely unfavorable for the command of the troops and the interaction of the fronts. "

The official Soviet account of the war did not go into this, claiming that the Stawka or the State Defense Committee found out about the German plans too late and therefore could not have done anything more. Nevertheless, the historian Joachim Hoffmann summarized in 1983: "The errors and omissions of the Soviet leadership are in any case a major reason why Army Group Center was able to break through the defense at the crucial points relatively quickly."

In the first Soviet publications after the Second World War, the encirclement and annihilation of a large part of the Red Army was sometimes not mentioned at all. Later, however, it was mainly the resistance of the Soviet units in the Vyazma pocket that was heroized . Both in the official account, as well as in the memoirs of Zhukov or Vasilevsky, one found the statement that the sacrifice of the five encircled armies was necessary to save the capital. The fact that the top German military leadership actually directed a large part of the existing forces (parts of Pz.Gr. 3 and the 9th Army) to the north against Kalinin, instead of advancing with them to Moscow, which was just as distant, was not mentioned. Later Soviet historiography also emphasized that the resistance of the trapped troops would ultimately have tied German divisions for about two weeks and thus prevented them from breaking through to Moscow:

“But the fighting of the encircled troops required the deployment of 28 enemy divisions, which freed up time to organize the defense on the Moshaisk line. The fighting at Vyazma tied the main forces of von Bocks' armored groups and armies at that critical time when his individual corps and divisions pushed into the breaches that had developed near Moscow and when the aggressor had no solid defense for a short time. "

On the German side, there were numerous "inaccuracies" in the later presentation of the operations. Some commanders, such as Heinz Guderian, falsely claimed that the encircled 50th Army had already surrendered on October 17th and the pocket near Bryansk had been cleared by October 20th. He did not mention the successful breakout of parts of the 3rd, 13th and 50th Soviet armies from the pocket. In other representations, the capitulation of the Vyazma Cauldron was dated October 13th. In fact, ended on October 12th. Although the major attempts to escape, the last trapped troops only surrendered seven days later, which in the meantime tied up important German forces. Recent research has attempted to correct these errors, but the incorrect data that has been adopted is found in numerous publications.

In the memoirs of the post-war years, the decision of Hitler and the OKH to turn off Panzer Group 3 and large parts of the 9th Army on Kalinin aroused great criticism. For example, Walter Chales de Beaulieu , former Chief of Staff of Panzer Group 4, wrote after the war:

"The XXXXI. The (northern) corps of this tank group with its fast divisions was not involved in the Vyazma containment ring, was available from October 8 for further action to the east, on Moscow, north of the autobahn, would have been reinforced by the SS division “Reich “ , On this particularly suitable operating line - distance from Vyazma, Moscow only 200 km! - be able to advance further and at that time hardly encountered insurmountable resistance. If one considers that this corps - headed north - reached Kalinin on October 13, which is only 200 km from Vyazma, but where far less favorable roads lead, one can imagine legitimate prospects for success before Moscow . "

In addition, German historiography often contains the thesis that the unusually early change in weather conditions surprised the German troops and that this fact led to the operation failing. In fact, the German leadership believed they could ignore Rasputitsa, which they expected in mid-October, since operations should then be over. Experts from the meteorological department were not involved in the planning. However, the precipitation in October remained below average, so that the autumn of 1941 was relatively dry. In addition, the frost set in earlier than usual, which further shortened the mud period. In view of the fact that the muddy period in 1941 was shorter and drier than usual, the thesis of a sudden change in weather conditions can be seen as an attempt “to ascribe the fault of one's own failure to a force majeure” .

Remarks

- ↑ There was no "Tymoshenko Army Group". What is meant is the "High Command of the Troops of the Western Direction" led by Marshal of the Soviet Union Semjon Konstantinowitsch Timoshenko , which was dissolved a little later. Tymoshenko was then transferred to the southwest front .

- ↑ According to other sources, the idea of a third grouping of collisions should have been based on the plans of Fedor von Bocks; see. Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 50 f.

- ↑ Hitler had these divisions re-equipped and refreshed in order to use them after a victory over the Soviet Union.

- ↑ Regarding operational tanks: 3. Pz.Div. 20%, 17th Pz Div. 17%, 4th Pz.Div. 29%, 18th Pz.Div. 31%, 20th Pz.Div. 34%, 11th Panzer Division 72%, 10th Panzer Division 88%, 2nd Panzer Division 94%, 5th Pz.Div. 100% as well as 1st, 6th and 7th Pz.Div. at about 30%; see. Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 54 f.

- ↑ Tyurin had already been warned on September 30th. In addition to some infantry units, he had four anti-tank regiments and a howitzer regiment at his disposal. Nevertheless, German troops were able to enter the city and occupy it. See AI Yeremenko: Days of Probation , Berlin (East) 1961, p. 125 f.

- ↑ According to a Führer order, the Panzer Group was in “2. Panzer Army ”has been renamed.

- ↑ So the Panzer Groups 3 and 4 were to advance to Vologda and the 2nd Panzer Army should reach Gorky . While the 2nd Army was to be turned off on Voronezh , the 4th Army alone remained for the conquest of Moscow. The furthest of these targets were up to 600 km from the starting position. For these plans and the differences of opinion about them, see: Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende vor Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, pp. 82–86.

literature

swell

- Walter Chales de Beaulieu : Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Scharnhorst Buchkameradschaft , Neckargemünd 1969.

- Heinz Guderian : Memories of a Soldier , Kurt Vowinckel Verlag , Heidelberg 1951.

- AI Yeremenko : Days of Probation , German Military Publishing House , Berlin (East) 1961.

- GK Schukow : Thoughts and Memories , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1969.

- Anton Detlev von Plato : The History of the 5th Panzer Division 1938 to 1945 , Regensburg 1978.

Secondary literature

- John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , Cassell Publ., London 2003. ISBN 978-0-304-36541-8 .

- David M. Glantz, Jonathan House: When Titans clashed - How the Red Army stopped Hitler , Kansas University Press, Kansas 1995. ISBN 978-0-7006-0899-7 .

- Joachim Hoffmann: The warfare from the perspective of the Soviet Union , in: Horst Boog, Jürgen Förster, Joachim Hoffmann , Ernst Klink, Rolf-Dieter Müller , Gerd R. Ueberschär : The attack on the Soviet Union (= Military History Research Office [ed.]: Das German Reich and the Second world war . band 4 ). 2nd Edition. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-421-06098-3 , pp. 713–809 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- AB Исаев ' Котлы 41-го. - История ВОВ, которую мы не знали , Яуза Эксмо, Москва 2005. ISBN 5-699-12899-9 ( online version ).

- Ernst Klink : Die Operationsführung , in: Horst Boog, Jürgen Förster, Joachim Hoffmann , Ernst Klink, Rolf-Dieter Müller , Gerd R. Ueberschär : The attack on the Soviet Union (= Military History Research Office [ed.]: The German Reich and the Second World War . Band 4 ). 2nd Edition. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-421-06098-3 , pp. 451–712 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Д. 3. Муриев: Вяземская операция , in: Советская военная энциклопедия , Vol. 2, Москва 1978 ( online version )

- PN Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Deutscher Militärverlag, Berlin (East) 1963.

- Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1972 (= contributions to military and war history , vol. 13). ISBN 3-421-01606-2 .

- Aleksandr M. Samsonow: The great battle before Moscow , publishing house of the Ministry of National Defense, Berlin (East) 1959.

- David Stahel: Operation Typhoon: Hitler's March on Moscow, October 1941. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2013. ISBN 978-1-107-03512-6 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 57.

- ↑ a b c Григорий Ф. Кривошеев: Россия и СССР в войнах ХХ века , Москва 2001.

- ^ A b c Kurt von Tippelskirch: History of the Second World War , Bonn 1956, p. 206.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , pp. 486–502.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , pp. 503–507.

- ↑ Printed in: Walther Hubatsch (Ed.): Hitler's instructions for warfare 1939–1945 , Munich 1965, pp. 174–177.

- ↑ Walther Hubatsch (ed.): Hitler's instructions for warfare 1939–1945 , Munich 1965, p. 175 f.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 568 f.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 570.

- ↑ Walther Hubatsch (ed.): Hitler's instructions for warfare 1939–1945 , Munich 1965, p. 177.

- ↑ a b Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 574.

- ↑ Heinz Guderian: Memories of a Soldier , Heidelberg 1951, p. 202.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 574 f.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 52 f.

- ↑ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 571.

- ↑ Cf. PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 280.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The failure of the German blitzkrieg concept before Moscow , in: Jürgen Rohwer / Eberhardt Jäckel (eds.): Kriegswende December 1941 , Koblenz 1984, p. 205.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 54 f.

- ↑ PN Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 278 f.

- ↑ AM Samsonow: The great battle before Moscow , Berlin (East) 1959, p. 53.

- ^ PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 281.

- ↑ David M. Glantz / Jonathan House: When Titans clashed - How the Red Arm stopped Hitler , Kansas 1995, p. 78.

- ↑ a b c d P.N. Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 282.

- ^ David M. Glantz / Jonathan House: When Titans clashed - How the Red Army stopped Hitler , Kansas 1995, p. 79.

- ↑ Joachim Hoffmann: The warfare from the perspective of the Soviet Union , p. 760 f.

- ↑ a b c Joachim Hoffmann: The conduct of war from the perspective of the Soviet Union , p. 761.

- ↑ a b K. K. Rokossowski: Soldiers' Duty , Berlin (East) 1968, p. 63.

- ^ John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, p. 214.

- ^ PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 283.

- ^ John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, pp. 214 f.

- ^ Oskar Munzel : Panzer-Taktik - Raids of armored units in the Eastern Campaign 1941/42 , Neckarmünd 1959, p. 103.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turn before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 63.

- ↑ a b c David M. Glantz / Jonathan House: When Titans clashed - How the Red Army stopped Hitler , Kansas 1995, p. 80.

- ^ A b John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, p. 216 f.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 64, fn. 109.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 66.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 66f, fn. 124 and 130.

- ^ John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, p. 219.

- ↑ Oskar Munzel: Panzer-Taktik - Raids of armored units in the Eastern campaign 1941/42 , Neckarmünd 1959, p. 106.

- ^ AI Yeremenko: Days of Probation , Berlin (East) 1961, p. 143 f.

- ^ W. Chales de Beaulieu: Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Neckargemünd 1969, p. 195.

- ↑ Quoted from: PN Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 285.

- ↑ W. Chales de Beaulieu: Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Neckargemünd 1969, pp. 195–197.

- ↑ a b P.N. Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 284.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turn before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 69.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 67.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 69 f.

- ↑ W. Chales de Beaulieu: Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Neckargemünd 1969, p. 196.

- ↑ a b Joachim Hoffmann: The conduct of war from the perspective of the Soviet Union , p. 763.

- ^ GK Schukow: Thoughts and Memories , Stuttgart 1969, p. 323.

- ^ A b W. Chales de Beaulieu: Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Neckargemünd 1969, p. 197 f.

- ^ John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, p. 217.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende vor Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42, Stuttgart 1972, p. 74, fn. 178.

- ^ GK Schukow: Thoughts and Memories , Stuttgart 1969, p. 321.

- ^ John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, p. 217 f.

- ^ A b John Erickson: The Road to Stalingrad , London 2003, p. 218.

- ↑ a b c P.N. Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 289.

- ^ PN Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 294.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turn before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 89; Joachim Hoffmann: The warfare from the perspective of the Soviet Union , p. 763.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The Turnaround Before Moscow - The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in Winter 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 76.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 79.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 80 f.

- ^ A b Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 65 f.

- ^ PN Pospelow (Ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 287.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 66 f.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The Turn Before Moscow - The Failure of Hitler's Strategy in Winter 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 70.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turn before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ On these struggles: PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, pp. 294–296.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 76 f.

- ^ A b W. Chales de Beaulieu: Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Neckargemünd 1969, p. 205.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 77 f.

- ^ Heinz Guderian: Memories of a Soldier , Heidelberg 1951, p. 210.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 73.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 73, fn. 165.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 578 f.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, pp. 79–81.

- ↑ Quoted from: Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende vor Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 81.

- ^ PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 300.

- ^ Heinz Guderian: Recollections of a Soldier , Heidelberg 1951, pp. 220-223.

- ↑ Quoted from: Klaus Reinhardt: Die Wende vor Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 86.

- ^ Ernst Klink: Die Operationsführung , p. 578.

- ^ PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 292.

- ↑ AM Samsonow: The great battle before Moscow, Berlin (East) 1959, p. 70f; Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 87.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life , Berlin (East) 1977, p. 135.

- ↑ For example: PD Korkodinow: The smashing of the German-fascist troops near Moscow , in: PA Schilin (ed.): The most important operations of the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945. Berlin (East) 1958, pp. 131-146.

- ^ PN Pospelow (ed.): History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union , Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 301; GK Schukow: Thoughts and Memories , Stuttgart 1969, p. 323.

- ↑ AM Samsonow: The battle before Moscow , in: Eberhard Jäckel (Ed.): Kriegswende December 1941 , Koblenz 1984, p. 188 f.

- ^ Heinz Guderian: Memories of a Soldier , Heidelberg 1951, p. 218.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turning point before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 65, fn. 118.

- ↑ For example: Janusz Piekalkiewicz: Battle of Moscow , Augsburg 1998.

- ^ W. Chales de Beaulieu: Colonel General Erich Hoepner , Neckargemünd 1969, p. 201 f.

- ↑ Klaus Reinhardt: The turn before Moscow - The failure of Hitler's strategy in the winter of 1941/42 , Stuttgart 1972, p. 78f and. Footnote 211; Quote, p. 78.