Donets Basin operation

The operation Donets Basin or Donbas operation ( Russian Донбасская операция , Donbasskaja operazija ') was a battle during the Second World War on the Soviet-German front from 16 August to 22 September 1943. The Soviet broke through southwestern and southern front first the German lines on the Donets and the Mius in the southern border area of Russia and Ukraine . Essentially, this was a successful resumption of the Donets-Mius offensive that had taken place shortly before and had largely failed in its objectives . Subsequently, the Red Army recaptured large parts of the economically important Donets Basin , including the cities of Mariupol , Taganrog and Stalino . Large parts of the German Army Group South had to withdraw behind the Dnepr .

background

The Donets Basin was particularly important as a coal mining area . Before the outbreak of war it provided about 60% of hard coal and 75% of coking coal the USSR. Furthermore, around half of all metallurgical companies, two thirds of the chemical industry and three quarters of the thermal power plants were located there. This industrial area accounted for 30% of iron production and 20% of steel production. In the summer / autumn of 1941 the industry was almost completely evacuated or destroyed. Under the management of the Berg- und Hüttenwerkgesellschaft Ost (BHO), the German occupying power produced 15,000 tons a day (July 1943), around 5% of the pre-war coal production.

From spring to summer 1943 there was hardly any significant fighting on the German-Soviet front. Only the German offensive against the Kursk Arch (→ Operation Citadel ) expected by the Soviet leadership , which began on July 5, 1943, triggered a further series of operations along the entire length of the front. In order to reduce the pressure of the German attacks in the Kursk area , the Red Army began three counter offensives as early as July 1943 near Leningrad (→ Third Ladoga Battle ), against the front arch at Oryol (→ Oryol Operation ) and on the southern wing of the front (→ Donets -Mius Offensive ). The latter operation was supposed to lead to the reconquest of the economically important Donez Basin , but failed after minor initial successes.

Although none of these offensives ultimately achieved their far-reaching goals, they tied up the few German reserves. Therefore, when further Soviet offensives were launched in the central section of the front in early August 1943 (→ Belgorod-Charkow Operation ; → Smolensk Operation ), the Wehrmacht leadership hardly had any reserve units worth mentioning to be able to stop them. The advance of the Red Army gained ground on several sectors of the front. To take advantage of this favorable moment, the Soviet leadership decided to make another attempt to recapture the Donets Basin. In early August 1943, the Soviet High Command instructed the South and Southwest Fronts to prepare new offensive operations, which were scheduled for the middle of the month.

German location

In the southern part of the Eastern Front, the German 6th Army was under General of the Infantry Karl-Adolf Hollidt on the Mius and the 1st Panzer Army under Colonel General Eberhard von Mackensen on the Donets . Both belonged to the Association of Army Group South of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein . However, these armies had been weakened and thinned out in favor of the Kursk Offensive. The term “Panzer Army” was misleading because it had no armored troops. Instead, it had the XXX in its inventory. Army Corps (three Inf. Div.), The XXXX. Panzer Corps (three Inf. Div.) And the LVII. Army Corps (three Inf. Div.). The 6th Army consisted of the XXIX. Army Corps (three Inf. Div., One combat group), the XVII. Army Corps (three Inf. Div.) And the Mieth (IV.) Corps (one Geb.Div., Two Inf.Div.). As a result of the previous fighting in the second half of July, the German troops had already suffered high losses in these sections that had not yet been replaced. The 6th Army alone had 3,298 dead, 15,817 wounded and 2,254 missing. The 384th Infantry Division, for example, was so thinned out that it had to be detached from the front. For a certain compensation, only the 17th Infantry Division and the 15th Air Force Field Division could be brought in.

During the fighting, the Soviet southern front managed to build a bridgehead on the western bank of the Mius. Only through the counterattack of several German tank divisions that had been withdrawn from the Kursk area could this be eliminated again. Thus the defense could again rely on the course of the river. The situation on the Donets was different: Here the Soviet south-western front had also captured a bridgehead that the Germans could not remove due to insufficient forces. The bridgehead therefore remained, as General Field Marshal von Manstein put it, a "festering wound in the front of the 1st Panzer Army." Since the German leadership expected a continuation of the Soviet offensive from this bridgehead, they concentrated here with the 16th Panzer Army. Grenadier Division and the 23rd Panzer Division were the only weak reserves of Army Group South behind the front.

Soviet planning

On August 6, 1943, just two days after the failed Donets-Mius offensive, the Soviet headquarters issued its directive number 30160. The Southwest Front under Colonel General RJ Malinowski and the South Front under Colonel General FI Tolbuchin received the order to prepare new operations. As in July, a concentric approach to Stalino was planned, which was to begin between August 13 and 14. To coordinate the action on both fronts, but also to improve cooperation with the neighboring fronts, the Chief of the Soviet General Staff, Marshal of the Soviet Union A.M. Wassilewski assigned to the southern theater of war as representative of the headquarters.

On August 7, 1943, Wassilewski arrived at the headquarters of the Southwest Front and worked out an operational plan with Colonel General Malinowski and the front staff. This envisaged a main thrust south of Isjum from the bridgehead on the other side of the Donets in the direction of Barvenkowo and Losowaja , Pavlograd and Sinelnikowo . The 6th Army (Gen. Lt. IT Schljomin ), the 12th Army (Gen. Maj . AI Danilow ) and the 8th Guard Army (Gen. Lt. VI Tschuikow ) were scheduled for the operation. The 23rd Panzer Corps (Gen. JG Pushkin ), the 1st Mechanized Guard Corps (Gen. IN Russijanow) and the 1st Guard Cavalry Corps were available as particularly mobile forces and were to be supported by the forces of the 17th Air Army .

On August 9, Wassilewski stayed at the headquarters of the southern front , where he and Colonel General Tolbuchin and his staff drafted the plans for the operations on the Mius. The efforts should therefore concentrate on a section only ten to twelve kilometers wide near Kuibyshevo . The 5th shock army (Gen. Lt. WD Zwetajew ) and the 2nd Guards Army (Gen. Lt. GF Sakharov ), supported by parts of the 28th Army (Gen. Lt. WF Gerasimenko ), were supposed to cross the Mius and force a breakthrough through the German defense. For this purpose, 120 guns were deployed per front kilometer, while the 51st Army (Gen. Lt. JG Kreiser ) was to conduct a support attack near Snezhnoye . After a successful breakthrough, the 2nd and 4th Mechanized Guards Corps and the 4th Guards Cavalry Corps were available to advance towards Stalino via Amwrossijewka and Starobeschewo . The 8th Air Army (General TT Chrjukin ) had to support this approach.

On August 10, 1943, Stalin as Supreme Commander and his headquarters confirmed the operational plans, which were practically nothing more than a foreseeable resumption of the offensives of July 1943. However, the problem still remained that the southern front had been weakened by the previous fighting. To compensate for this disadvantage, Wassilewski was given permission to attack this front two days later than the southwest front . When the preparations for the new offensives were completed, the two Soviet fronts finally had 1,053,000 soldiers, 21,000 artillery pieces and grenade launchers, as well as 1,257 tanks and self-propelled guns , supported by 1,400 aircraft.

course

The attack on the southwest front until the end of August 1943

On August 13, 1943, the troops on the southwest front began an attack over the Donets south of Kharkov . There they deployed three armies to support the steppe front advancing to the north in taking the city. Although this operation had no connection with the fighting in the Donets Basin, hundreds of kilometers away, the date in Soviet historiography marks the official start of the "Donets Basin Operation".

In fact, it was not until August 16, 1943 that the Soviet 6th and 12th Army and the 8th Guard Army took to attack from the bridgehead near Isjum. According to German information, eleven rifle divisions and 130 batteries are said to have been deployed on the Soviet side on the first day. The focus of the attack was in the area of the Soviet 12th Army south of Isjum. In the first hours of the offensive, the attack formations broke into the positions of the German 46th Infantry Division . However, a counterattack by the German 23rd Panzer Division blocked it in the afternoon and recaptured the lost terrain by evening. In the days that followed, the fighting was concentrated in Dolgenkaya . From August 16 to 27, 1943 , the southwest front deployed a total of nine rifle divisions, nine tank brigades, a guard tank regiment and a motorized rifle brigade. Although the Red Army repeatedly broke deep into the German positions, counterattacks by the German 23rd Panzer Division, 16th Panzer Grenadier Division and 17th Panzer Division immediately afterwards inflicted heavy losses and threw them back.

These attacks and counter-attacks turned out to be costly for both sides. Since there is no precise information on the total losses, only a few figures can be given as examples. The 23rd Panzer Division alone, which was the focus of the fighting, reported the shooting down of 302 enemy tanks. However, she herself had lost 71 officers and 1746 NCOs and men. After twelve days of fighting, the division therefore had hardly any infantry forces. On the Soviet side, the loss-making and fruitless attacks led to a rethink. Marshal Wassilewski and Colonel-General Malinowski decided to "stop the pointless running up" and instead try a breakthrough elsewhere. To this end, Lieutenant General Chuikov's 8th Guard Army was to be moved further east. Several days were planned for the regrouping of the troops. The German 1st Panzer Army had thus repulsed the offensive on the Soviet Southwest Front for the time being.

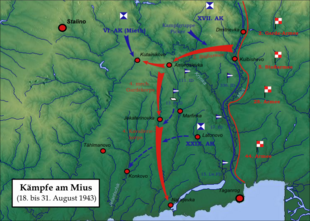

The attack on the southern front until the end of August 1943

“The earth trembled, and a roar like an endless rolling clap of thunder began. This rumbling lasted for more than an hour, interrupted from time to time by 'Katyusha' volleys that thundered like avalanches [...] A black, impenetrable wall of smoke and dust stood over the opposing position. The artillery did its work of destruction. "

SS Biryusov (Chief of Staff of the Southern Front )

On August 18, 1943, Colonel General Tolbuchin's southern front finally attacked across the Mius. In the previous days, smaller regimental advances were intended to improve the Soviet base. On the morning of the day that made the main attack southern front the 5 o'clock barrage fall on the German lines of 5000 guns and mortars. Of these, 2000 were combined in the attack strips of the 5th Shock Army and 2nd Guard Army, which were just a few kilometers wide, where 120-200 guns (the information varies) came to a front kilometer. Shortly afterwards, 17 Soviet divisions and four tank brigades advanced against the defensive positions of three German divisions. While the 306th and 336th Infantry Divisions were able to hold their positions, the position of the 294th Infantry Division of the XVII. Army corps literally overrun. On the first day of the attack, the Soviet troops broke in here ten kilometers deep. Even quickly brought in blocking formations of the 111th Infantry Division could not block the breakthrough, so that the Soviet 5th Shock Army advanced another twelve kilometers to the west by the evening of August 19, reached the Krynka and was able to build a bridgehead on the other bank. That same evening, Colonel-General Tolbuchin had Lieutenant General Tanashchishin's 4th Mechanized Guard Corps introduced through the gap in the German defense and expanded the breakthrough.

The few reserves of Army Group South were already tied up in the fighting on the Donets, so that the 6th Army had to make do with its small units, which, however, were already in the front. It could hardly do anything to counter the approximately 800 tanks and self-propelled guns on the southern front , but Colonel-General Hollidt saw an opportunity to rectify the situation by launching counterattacks against the base of the Soviet breakthrough. This was only three kilometers wide south of Kalinowka, which led to the hope that the 5th Shock Army could be cut off here. Under the orders of the commander of the 3rd Mountain Division , Major General Egbert Picker , only five battalions, six batteries, one assault gun battery and two tank destroyer companies could be brought together from the area of the IV Army Corps attacked the Soviet northern flank. The attack made good progress at first, but then Tolbuchin had the 4th Mechanized Guard Corps turn around and counterattack. Although it was possible to shoot down 84 Soviet tanks, the "Kampfgruppe Picker" was pushed back on August 21. In the next two days, the Soviet units succeeded in widening the gap in the German front to nine kilometers. From the Krynka, the mechanized units of the Red Army started a further advance and captured the important traffic junction Amvrosievka on 23 August. After the failure of the counterattacks, the defense of the Germans now relied on the course of the Krynka southeast of Kolpakowka, although the Soviet troops had already overcome this river further north.

In the meantime, reinforcements from Army Group A arrived, including the 13th Panzer Division . However, this “division” only had the strength of a Panzergrenadier regiment with seven tanks. This association was initially used unsuccessfully on 23 August by the “Kampfgruppe Picker”. Then she was in forced marches to the area of the XXIX. Army corps moved south of the Soviet breakthrough to strengthen the defense on the Krynka.

The 25th and 26th of August passed with regroupings and the replenishment of ammunition stocks on the part of the Red Army. On the morning of August 27, 1943, another phase of the Soviet offensive began, which included the encirclement of part of the German 6th Army. The 4th Mechanized Guard Corps and the 4th Cavalry Corps attacked southwards from the Amvrosievka area. The cavalry should the German XXIX. Include Army Corps, while the 4th Mechanized Guard Corps was to shield this operation to the west. On August 28, the most important German routes of retreat were cut off. The next day the cavalrymen reached the Mius- Liman near Nataljewka via Ekaterinovka . The counterattacks of the 13th Panzer Divisions against the containment movement were unsuccessful. In the war diary of the 6th Army was the situation of XXIX. Army corps of the General of the Armored Troops Erich Brandenberger noted:

“The telephone connection with the corps was interrupted. It had to be expected every hour that the units would split up and the corps would break up into individual groups. "

Indeed, Soviet pressure increased from all sides. The 2nd Guards Army and 28th Army attacked from the north, while the 44th Army advanced directly on Taganrog . The sea route was also blocked by the Soviet Azov flotilla under Rear Admiral SG Gorschkow , which also landed troops. On August 30th, Taganrog was finally captured.

When on August 27, 1943 the enclosure of the XXIX. Army Corps emerged, the 6th Army High Command took hasty action. It ordered the corps to deport its rear services to Mariupol and, under the command of the commanding general of the IV Army Corps, General of the Infantry Friedrich Mieth , assembled troops for a counterattack. These included the bulk of the 3rd Mountain Division and the 17th Panzer Division, which had been brought in from the Donets. With these troops General Mieth attacked repeatedly to prevent further advance of the Red Army and reached the area north of Kuteinikowo on August 30th. At this time, the infantry divisions of the XXIX. Army Corps from their previous positions. The 13th Panzer Division under the corps led the breakthrough attempt from August 30th. The following day - the four divisions of the XXIX. Army corps were concentrated on an area of about 25 km², which was under Soviet artillery fire - the troops of General Brandenberger managed to break out south of Konkowo. During the night, both corps moved west on the Jelantschik. However, the enclosed divisions had suffered heavy losses. For example, the Air Force Jäger Regiment 30 of the 15th Air Force Field Division numbered only 400 of the original 2,400 soldiers.

The struggle to withdraw

Since all efforts of the 6th Army had failed to stop the Soviet advance, Field Marshal von Manstein came to the conclusion that the south wing of his Army Group Front could no longer be held. Even before the Soviet breakthrough, he had given the eleven divisions of the 6th Army only a combat value of four divisions. He therefore demanded from Hitler either freedom of movement or the delivery of considerable reinforcements. In a meeting in Vinnitsa on August 27, Hitler promised further units, but in the following days it became apparent that divisions could not be dispensed with anywhere in order to add them to Army Group South . He forbade a complete evacuation of the Donets Basin, however. After the temporary enclosure of the XXIX. Army Corps, however, arbitrarily gave the 6th Army the order to avoid the prepared "turtle position", a line of defense along the Kalmius east of Stalino. Not until the following day did Hitler subsequently approve this step.

The disputes about the evacuation of the Donets Basin, but also about a larger retreat, took place under the impression of the setbacks along the entire front since the breakup of the battle in the Kursk Arc. As early as the spring, the General Staff had demanded the construction of a rear line of defense, which Hitler categorically rejected. It was not until August 12, 1943, that Hitler finally gave in and approved the construction along the Dnepr (→ Panther position ). However, he initially prohibited all evasive movements. He declared that without the coal from the Donets Basin the war would be lost. When the Chief of Staff General of the Infantry Kurt Zeitzler checked this claim in the Ministry of Armaments, the Minister of Armaments Albert Speer informed him that this was not the case and that the coal from this area had not been included in the economic calculations at all. Thereupon Hitler also forbade the Chief of Staff from making contact with other ministries.

However, since the Soviet units made further progress and Hitler refused to give in during a meeting at his headquarters in East Prussia on September 4, Manstein felt compelled to ask him for another meeting at the headquarters of Army Group South in Zaporozhye . There he once again explained the hopeless situation to Hitler on September 8th. Hitler finally agreed to a retreat to the Dnieper, but ordered that this should only be done gradually and slowly. On the same evening, General Field Marshal von Manstein ordered the 6th Army and the 1st Panzer Army to switch to mobile defensive combat.

The retreat to the Dnepr

After the 6th Army had been ordered to withdraw into the “turtle position” on August 31, 1943, it gradually began to move westward. On September 4th, their units reached the new line of defense. The troops of the Soviet southern front pushed in after the Germans. In order to increase their effectiveness, the Soviet High Command added the 20th Panzer Corps (Lieutenant General IG Lasarew) and the 11th Panzer Corps (Major General NN Radkewitsch) to this front on September 2, 1943.

Due to the withdrawal of the 6th Army, the 1st Panzer Army had to withdraw its right wing. The Soviet southwest front tried to take advantage of this and attacked Isjum on 3rd / 4th. September again. Again, the attack by the 6th and 8th Guard Army remained in the German defensive fire. But on the eastern wing, where the units of the 1st Panzer Army followed the evasive movement of the 6th Army, the 3rd Guard Army under General Lelyuschenko was able to gain more space. Proletarsk, Popasnaya and Artyomovsk fell in quick succession. Colonel-General Malinovsky and Marshal Wassilewski decided to pull the 1st Mechanized Guard Corps and the 23rd Panzer Corps out of the rest of the front, thereby strengthening Leljuschenko's troops. With the help of these reinforcements, the Soviet troops broke through the right wing of the 1st Panzer Army at Konstantinovka on September 6, 1943 . This opened a gap between the 6th Army and the 1st Panzer Army, which soon widened to 60 kilometers. Only remnants of two German divisions fought in this gap. So parts of the 5th shock army and 2nd guard army in street fighting on 7/8. September 1943 capture Stalino. Two days later, Mariupol and Barvenkowo also fell.

General Lelyuschenko's 3rd Guard Army, subordinated to the 1st Mechanized Guard Corps and 23rd Panzer Corps, had advanced far to the west after their breakthrough at Konstantinovka and were already near Pavlograd in the rear of Army Group South . The Army Group reacted with hasty improvisations. It contained the remnants of the 23rd Panzer Division, 16th Panzer Grenadier Division and the newly arrived 9th Panzer Division under the command of the XXXX. Panzer Corps, which was commanded by General of the Panzer Force Sigfrid Henrici . This put the three divisions on September 9 from the north and south against the flanks of the Soviet advance, which were held by rifle divisions. In heavy fighting they managed to close the gap between the 1st Panzer Army and the 6th Army at Slavyanka by September 12, thereby cutting off the bulk of the two Soviet corps.

Finishing off the operations

After the greatest threat to Army Group South had been averted for the moment , Field Marshal von Manstein decided to take a bold step. Since the north wing of his army group was also under steadily increasing Soviet pressure, he reported to the Army High Command on September 14, 1943 that he would arbitrarily order parts of his army group to set down on the Dnepr the following day. Thereupon there was another meeting with Hitler at his headquarters the following day. Since Hitler could no longer oppose Manstein's arguments, he finally agreed to the general withdrawal. On September 16, 1943, Army Group South and Army Group Center were allowed to retreat to the "panther position".

Meanwhile, the Soviet units were in the line of Losovaya- Chaplino- Guljai-Pole -Ursuf. But they too had suffered heavy losses. The last reserve of the Southwest Front , the 30th Rifle Corps, had to be added to the 3rd Guard Army to make up for the losses caused by the counterattack by the German XXXX. Panzer Corps had emerged. As a result, they no longer followed the German troops so energetically as they withdrew, although there were still fierce retreat skirmishes locally. After a few days, the Soviet units on the Southwest Front reached the Dnieper on September 22, 1943. The German 1st Panzer Army had been able to retreat to the other bank in time. Only in the Nikopol area did the German XVII. Army Corps had a bridgehead on the eastern side. The other two army corps of the 6th Army settled in an extension of the “Panther Line”, which ran along the Molotschna (east of Melitopol ) and was called the “Wotan position”. She was no longer since the Sept. 16, 1943 Army Group South , but the Army Group A . It was followed by the Soviet southern front until the front came to a standstill at the end of September.

consequences

losses

Official Soviet figures speak for the Donets Basin operation of 273,522 men in total casualties. Of these, 66,166 soldiers were killed or reported missing. In addition, 886 tanks and self-propelled guns, 814 guns and grenade launchers and 327 aircraft were lost. The German losses during this period have not been proven. However, the losses of at least the units that had been at the focus of the fighting were very high. For example, the 3rd Mountain Division, which on August 18th had given a total of 2,000 men to the “Kampfgruppe Picker”: of these, fewer than 200 returned five days later. The 15th Air Force Field Division also had to be disbanded a short time later. The material losses were particularly heavy. The 2nd Division of the 23rd Panzer Regiment (from the 23rd Panzer Division) was only in Germany in the summer with 85 Pz.Kfw tanks. V "Panther" has been equipped. With these, the division only got into retreat fighting at the beginning of September 1943 and lost all but five tanks by September 16, 1943.

It is difficult to estimate the casualties of the civilian population, as it is not possible to determine what the total population was at the time of the fighting and the latter spread over a large area with numerous localities. The German occupation policy in previous years and the deportations in the course of the evacuation of these areas also represent an important but hardly predictable factor. What is certain is that in 1940 Stalino had over 507,000 inhabitants. When the city was recaptured in September 1943, only 175,000 people lived there. Shortly thereafter, however, there were further casualties among the civilian population due to mass arrests carried out by the NKVD . Thousands of Soviet citizens were charged and convicted of collaboration . In the absence of precise figures, it must be taken as a guide that no fewer than 3,364 people were rehabilitated from Stalino alone in the 1990s. Soviet historians also assume that at least as many residents of the city were also convicted but not rehabilitated.

Burned earth

Since Hitler attached great economic value to the Donets Basin, he ordered the destruction of all industrial facilities. On August 31, 1943, he appointed General of the Infantry Otto Stapf to be responsible for this “evacuation” as head of the “Eastern Economic Staff”. However, the rapidly changing situation at the front did not allow for a scheduled evacuation, so that Field Marshal von Manstein now independently ordered the extensive destruction of all economic facilities:

"Everything that cannot be transported away is subject to destruction, pumping stations and energy centers, in general all power plants and transformer stations, shafts, operating facilities, means of production of all kinds, grain that can no longer be transported away, settlements and houses."

A total of 284,000 civilians were killed and 268,000 tons of grain, 280,000 cattle, 209,000 horses, 363,000 sheep, 18,700 pigs, 800 tractors and 820 trucks were taken along on the retreat. Another 941,000 tons of grain, 13,000 head of cattle, 635 trucks and 10,800 tractors were destroyed. Industrial centers such as those in Stalino or Mariupol were also destroyed. The representative of the National Committee for Free Germany Friedrich Wolf was in the Donets Basin these days and reported to his wife on October 2, 1943:

“All of Mariupol burned, blown up. We were there ten hours after the Germans. Mines were laid in all houses, everything systematically blown up, regardless of whether old women and children were still in them. "

However, the destruction turned out to be unsustainable. As early as February 1943, when the first signs of a reconquest of the Ukrainian industrial areas (→ Voronezh-Kharkiv Operation ), the Soviet government had made preparations for the reconstruction of the Donets Basin and issued appropriate directives. After the Soviet success, these proved to be so effective that at the end of 1943 the coal mines of the Donets Basin again covered around 20% of Soviet coal production. By 1945, 7,500 businesses were restored there.

attachment

literature

- С.С. Бирюзов: Когда гремели пушки . Москва 1961 (German SS Birjusow: When cannons thundered ).

- Владимир Дайнес: Советские ударные армии в бою . Москва 2009 (German W. Dajnes: Soviet shock armies in combat ).

- А.Г. Ершов: Освобождение Донбасса . Воениздат, Москва 1973 (Ger. AG Publication: The Liberation of the Donets Basin ).

- Karl-Heinz Frieser (Ed.): The German Reich and the Second World War Volume 8: The Eastern Front 1943/44 - The War in the East and on the Side Fronts . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt , Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-421-06235-2 .

- Erich von Manstein: lost victories . Bernard & Graefe Verlag for Defense, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-7637-5051-7 .

- Norbert Müller (ed.): The fascist occupation policy in the temporarily occupied territories of the Soviet Union (1941-1944) . Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-326-00300-5 .

- PN Pospelow u. a .: History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Volume 2, Berlin (East) 1963.

- PA Shilin (ed.): The main operations of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 . Berlin (East) 1958.

- AM Wassilewski: A matter of whole life . Berlin (East) 1977.

Individual evidence

- ^ PN Pospelow u. a .: History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 263.

- ↑ Christoph Dieckmann : Cooperation and Crime - Forms of "Collaboration" in Eastern Europe 1939-1945 . Göttingen 2003, p. 212.

- ^ PN Pospelow u. a .: History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Vol. 3, Berlin (East) 1964, p. 374.

- ↑ See the schematic structure of the war, as of July 7, 1943 . In: Percy M. Schramm (Ed.): War Diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht . Vol. 3, Bonn 2002, p. 732.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 343.

- ↑ a b S.W. Maljantschikow: The Liberation of the Donets Basin . In: PA Shilin (ed.): The most important operations of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 . Berlin (East) 1958, p. 297.

- ↑ Erich von Manstein: Lost victories . Munich 1976, p. 517.

- ↑ Владимир Дайнес: Советские ударные армии в бою . Москва 2009, p. 605 f.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 314.

- ↑ a b A.M. Wassilewski: A matter of whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 314.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007 p. 357; Г.Ф. Кривошеев: Гриф секретности снят - Потери Вооруженных Сил СССР в войнах, боевых дейаных виях и военаныл . Москва 1993, p. 192.

- ↑ Percy M. Schramm (Ed.): War diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht . Vol. 6, Bonn 2002, p. 960 (entry from August 17, 1943).

- ↑ These were the 25th, 27th, 39th, 47th and 82nd Guards Rifle Divisions, the 263rd, 267th, 350th and 361st Rifle Divisions, the 16th and 9th Guards Tank Brigade, the 11th, 115th, 179th, 212th, 3rd, 39th and 135th Tank Brigades, the 10th Guards Tank Regiment and the 56th Motorized Rifle Brigade. These belonged not only to the 12th Army, but also to the 23rd Panzer Corps and the 1st Mechanized Guard Corps, i.e. forces that were supposed to be used only after a breakthrough. See Ernst Rebentisch: On the Caucasus and the Tauern - The History of the 23rd Panzer Division 1941–1945 . Esslingen 1963, p. 242.

- ↑ A detailed description of the fighting can be found in: Ernst Rebentisch: To the Caucasus and to the Tauern - The history of the 23rd Panzer Division 1941–1945 . Esslingen 1963, pp. 232-243.

- ^ Ernst Rebentisch: On the Caucasus and the Tauern - The History of the 23rd Panzer Division 1941–1945 . Esslingen 1963, p. 242 f.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 322.

- ↑ С.С. Бирюзов: Когда гремели пушки . Москва 1961, p. 180 f.

- ^ Paul Klatt: The 3rd Mountain Division 1939-1945 . Bad Nauheim 1958, p. 166.

- ^ Paul Klatt: The 3rd Mountain Division 1939-1945 . Bad Nauheim 1958, p. 167.

- ^ PN Pospelow u. a .: History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 374 f.

- ^ Paul Klatt: The 3rd Mountain Division 1939-1945 . Bad Nauheim 1958, p. 168 f.

- ↑ SW Maljantschikow: The Liberation of the Donets Basin . In: PA Shilin (ed.): The most important operations of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 . Berlin (East) 1958, p. 301.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 357 f.

- ↑ Friedrich von Hake: That was us! We experienced that! - The fate of the 13th Panzer Division . Hanover 1971, pp. 166-168.

- ↑ SW Maljantschikow: The Liberation of the Donets Basin . In: PA Shilin (ed.): The most important operations of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 . Berlin (East) 1958, p. 302.

- ↑ Quoted from: PN Pospelow u. a .: History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 376.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 323 f.

- ^ PN Pospelow u. a .: History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union . Vol. 2, Berlin (East) 1963, p. 376; SW Maljantschikow: The Liberation of the Donets Basin . In: PA Shilin (ed.): The most important operations of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 . Berlin (East) 1958, p. 302 f; Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 358; Percy M. Schramm (ed.): War diary of the high command of the Wehrmacht . Vol. 6, Bonn 2002, p. 1036 u. 1040 f (entry from August 31 and September 1, 1943); Friedrich von Hake: That was us! We experienced that! - The fate of the 13th Panzer Division . Hanover 1971, pp. 169-172.

- ↑ Werner Haupt : The German Air Force Field Divisions 1941-1945 . Eggolsheim 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Erich von Manstein: Lost victories . Munich 1976, p. 520 u. 523 f.

- ↑ Bernd Wegener: The aporia of the war . In: Karl-Heinz Frieser (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 269 f.

- ^ Entry on August 12, in: War diary of the OKW . Vol. 3, Augsburg 2002, p. 933.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 361.

- ↑ Erich von Manstein: Lost victories . Munich 1976, p. 526 f.

- ^ A b Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 358.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 325.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 326.

- ↑ SW Maljantschikow: The Liberation of the Donets Basin . In: PA Shilin (ed.): The most important operations of the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945 . Berlin (East) 1958, p. 301.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007 p. 358; in detail: Ernst Rebentisch: On the Caucasus and the Tauern - The History of the 23rd Panzer Division 1941–1945 . Esslingen 1963, pp. 250-256.

- ^ Karl-Heinz Frieser: The retreat operations of Army Group South in Ukraine . In: ders. (Ed.): The Eastern Front 1943/44 . Munich 2007, p. 362.

- ↑ AM Wassilewski: thing of the whole life . Berlin (East) 1977, p. 327 f.

- ↑ Григорий Ф. Кривошеев: Россия и СССР в войнах ХХ века . Олма-Пресс, Москва 2001, p. 192 u. 370 ( online version )

- ^ Paul Klatt: The 3rd Mountain Division 1939-1945 . Bad Nauheim 1958, p. 172.

- ↑ Werner Haupt: The German Air Force Field Divisions 1941-1945 . Eggolsheim 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Ernst Rebentisch: On the Caucasus and the Tauern - The History of the 23rd Panzer Division 1941–1945 . Esslingen 1963, pp. 253-256.

- ^ Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Daniel J. Walkowitz: Workers of the Donbass speak - Survival and identity in the new Ukraine . Albany 1995, p. 11.

- ↑ Christoph Dieckmann: Cooperation and Crime - Forms of "Collaboration" in Eastern Europe 1939-1945 . Hamburg 2005, p. 191.

- ↑ See his instructions, in: Norbert Müller (Ed.): The fascist occupation policy in the temporarily occupied territories of the Soviet Union (1941–1944) . Berlin 1991, pp. 467-470.

- ^ International Military Court, Vol. XXXVI, p. 307 f; see. also: Order of the High Command of the 6th Army for material evacuation in the Donets Basin (September 1, 1943). In: Norbert Müller (ed.): German occupation policy in the USSR 1941–1944 . Cologne 1980, p. 342 f.

- ↑ See report by the South Economic Inspectorate on evacuation, destruction and forced evacuation during the German withdrawal from the Donets region . In: Norbert Müller (ed.): The fascist occupation policy in the temporarily occupied territories of the Soviet Union (1941–1944) . Berlin 1991, p. 519.

- ↑ For a concrete list of the destruction, see: Final report of the 6th Army (October 16, 1943). In: Norbert Müller (ed.): The fascist occupation policy in the temporarily occupied territories of the Soviet Union (1941–1944) . Berlin 1991, pp. 489-492.

- ^ Friedrich Wolf: Letters . Berlin (East) 1958, p. 37.

- ^ Walter Scott Dunn: The Soviet economy and the Red Army 1930-1945 . Westport 1995, p. 45.