3rd Mountain Division (Wehrmacht)

|

3rd Mountain Division |

|

|---|---|

Troop Identification: The Narvik Shield |

|

| active | April 1, 1938 to May 8, 1945 |

| Country |

|

| Armed forces | Wehrmacht |

| Armed forces | army |

| Branch of service | Mountain troop |

| Type | Mountain Division |

| garrison | Graz |

| Second World War | Weser exercise company |

| Commanders | |

| list of | Commanders |

The 3rd Mountain Division was a large unit of the mountain troops of the Wehrmacht in World War II . The division was formed in April 1938 after the "Anschluss" of Austria to the German Reich from units of the Austrian Armed Forces .

After a brief deployment in the attack on Poland in 1940, he took part in the Weser Exercise Company , with a regiment from the division taking part in the Battle of Narvik .

During Operation Barbarossa , the division was involved in the advance on Murmansk . The losses suffered were so great, however, that the remnants had to be withdrawn from the front in 1941. After a later reorganization, the 3rd Mountain Division was transferred to Army Group North , then in the course of the Battle of Stalingrad to Army Group South with subsequent retreat to Romania until mid-1944. In the last months of the war the division fought in Hungary and Czechoslovakia , where it was on May 8 he capitulated to the Red Army at Deutsch Brod .

history

Lineup

The 3rd Mountain Division was one of five divisions that were formed from units of the Federal Army shortly after the "Anschluss" of Austria in March 1938. The 2nd Mountain Division , the 44th and 45th Infantry Division and the 4th Light Division were also set up from the former army units .

The 3rd Mountain Division emerged from the 5th and 7th Divisions of the Austrian Armed Forces and was set up on April 1, 1938 in Graz by Military District XVIII.

Structure of the division on April 1, 1938:

- Gebirgs-Jäger-Regiment 138, regimental staff, I. Batl. and 16. (Pz. Abw.) Kp. Leoben , II. Batl. Graz, III. Batl. Admont , remaining regimental units in Pinkafeld and Bad Radkersburg

- Gebirgs-Jäger-Regiment 139, Regimental Staff, I. Batl. and 16. (Pz. Abw.) Kp. Klagenfurt , II. Batl. Villach , III. Batl. Wolfsberg

- Mountain Artillery Regiment 112 in Graz, Leoben and Villach

- Gebirgs-Panzerjäger-Department 48 in Graz

- Mountain Pioneer Battalion 83 in Graz

- Mountain News Department 68 in Graz

- Mountain Reconnaissance Division 112

- Divisional Resupply Force 68

The division was mostly composed of Styrians and Carinthians , the 2nd Mountain Division, which was set up at the same time, was again mainly formed from Tyroleans , Vorarlbergers and Salzburgers . While in the other "Austrian" divisions the proportion of Austrians fell more and more in the course of the war due to the high losses in the war against the Soviet Union, this remained at a high level in the mountain divisions due to their special character until the end of the war.

Since only around 75 percent of the Austrian officers were taken over into the Wehrmacht and many of them could only be employed as so-called supplementary officers for reasons of age , there was a massive transfer of officers from the Wehrmacht (mainly from Bavaria , Württemberg and Silesia ) to the new ones Wehrmacht units deployed on Austrian soil. In some units the proportion of officers from the Old Reich was up to 50 percent. An Austrian chief of staff was also assigned to a German commander in many leading positions, or vice versa. This also applied to the 3rd Mountain Division, where the new commander, the Bavarian Eduard Dietl , was assigned to the Carinthian Julius Ringel as chief of staff .

The troop identification of the division, which it carried from 1940, was reminiscent of the battles for Narvik, which were waged by the mountain troops and members of the navy and the air force . It is very similar to the Narvik Shield donated for this fighting .

Calls

Sudeten crisis in 1938

At the beginning of September 1938 the division was mobilized . As with the other Wehrmacht divisions set up in the area of what is now the Ostmark , the mobilization concept of the army was used for this. A large part of the equipment used in most of these divisions was still of Austrian origin.

The units of the 3rd Mountain Division then moved to the Wiener Neustadt - Semmering area , where exercises were carried out in the battalion or regimental framework. In the course of the Sudeten crisis , the 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions were placed under the XVIII. Mountain Corps . On October 1, 1938, the German troops marched into Czechoslovakia , with the 3rd Mountain Division being assigned the Znojmo area as a target. There was no fighting with this occupation. In the course of October, the division's units returned to their locations, where the first recruits were drafted from the beginning of November .

When the rest of the Czech Republic was broken up from March 15 , the 3rd Mountain Division was not used.

attack on Poland

- Use from September 1st to 13th

The division was mobilized on August 26th and from August 28th it was moved by rail to the Rosenberg area in Silesia , where it was ready to take part in the attack on Poland . The 3rd Mountain Division, along with the 2nd Panzer Division and the 4th Light Division, belonged to the XVIII. Mountain Corps that was part of the 14th Army . For a short time it formed the extreme right wing of Army Group South , to which the 14th Army belonged, before the 2nd and 1st Mountain Divisions were deployed east of it over the next few days .

While the units of the 3rd Mountain Division crossed the Tatra Mountains over the Huty Pass on September 1st and marched into Poland, Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 was assigned to the 4th light division . It was supposed to assist this division in their advance on Cracow . Since the mountain fighters marching on foot could not keep up with the speed of the faster motorized units for long, the regiment was returned to the division on September 5th in the area of Myślenice .

After a brief firefight with border troops, the division marched in the next few days without the Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139, largely unmolested by the Polish army via Habovka , Chocholow to Rabka . At Nowy Targ and at Mszana Dolna the reconnaissance department 112 and the Jg.Rgt. 138 involved in fighting that resulted in casualties on September 3rd. More battles took place a day later at Kasina Wielka. After that, the Polish units mostly withdrew from the mountain troops so that major fighting did not take place. On September 6th the Dunajec was crossed. Further rivers on the way were the Biala , Wisloka and the Wislok . Finally, on September 12, the San was crossed at Sanok and the area around Olszanica was reached. There parts of the division were loaded onto trucks to be transported to the 2nd Mountain Division to support them in their advance on Przemysl . A day later the division was stopped and ordered back to the Prešov area .

For the 3rd Mountain Division, the attack on Poland was over, after arriving in the assembly room in Prešov, starting on September 18, they were transported to the west.

- Self-fire, riot frenzy and looting

While in the division history (Paul Klatt: Die 3. Gebirgs-Division, 1939-1945 ) the time of the first days of the campaign was described as "calm, apart from skirmishes and weaker enemy resistance", the evaluation of field post letters and reports of experiences from division members was characterized and members of the corps troops of superior XVIII. Mountain Corps a differentiated picture.

In the first days of the war there was extreme nervousness among the inexperienced German soldiers, which resulted in shootings without any specific reason.

This mood was exacerbated by the fact that the Polish army in the area of the XVIII. Mountain Corps did not face an open field battle, but quickly withdrew to the east. Only occasionally did the rear guards or individual groups of Polish soldiers fire at the advancing German units. This form of warfare was nerve-wracking for the German soldiers and their fears were often projected onto the Polish civilians, who were presumed to have been ambushed fighters against the German troops. The German soldiers then often reacted spontaneously and liquidated the alleged riflemen among the civilian population without first investigating the case carefully or forwarding it to the superior departments for investigation. According to Polish research after the war, the number of civilians killed was in the thousands.

An officer of the Corps News Department 70, who was part of the corps troops of the XVIII. Mountain Corps, made the following observations on September 2, when the corps staff changed position from Jabłonka to Rabka and got into the advance area of the 3rd Mountain Division:

“The division's advance routes are clearly visible. We drive past endless columns and burning houses towards the front ..... Dead Polish civilians lie in the most bizarre contortions in the field next to the road. Spies and snipers. Everyone is looking, I notice, but hardly anyone grimaces. 'War', everyone thinks. "

Polish investigations after the war showed that in the villages of Klikuszowa and Niedźzwiedź , both south of Rabka, several civilians were killed by the German troops and houses were set on fire after German units were bombarded by retreating Polish forces.

Another side effect of the German invasion was that German soldiers increasingly began to plunder the occupied territories. Several members of the division were also sentenced to several years' imprisonment for theft by the court martial of the 3rd Mountain Division.

Security service in the west 1939/40

The division was first relocated to the Bad Dürkheim area and then used from October 1 to 10, 1939 on the Lauter in the Palatinate Forest in the main battle line. In mid-October 1939, the units moved to the Hunsrück and the area around Bernkastel . At the end of October 1939 another relocation took place in the Voreifel and after a few days further to the Kochem area .

In January 1940 the company relocated to the Karden - Moselkern - Hatzenport area. At the beginning of March 1940, the division was concentrated in the Döberitz area and held ready for the occupation of Norway .

Operation Weser exercise and occupation time in Norway 1940/41

The 3rd Mountain Division was divided into several combat groups for the occupation of Norway as part of the Weser Exercise company . Part of the Jg.Rgt. 139 (approx. 2000 men of the so-called S-Squadron ) was transported by ten destroyers to Narvik and occupied the city in the morning hours of April 9, 1940. After British warships had destroyed all ten German warships on April 10 and 13, the surviving sailors were used infantry against more than 20,000 Allied soldiers from Great Britain , France , Poland and Norway. Narvik was evacuated by the Wehrmacht on April 24th and the fighting then shifted to the hinterland of the city. The strategic turn came with the German offensive against France on May 10th, as a result of which the Allies began on May 24th to re-embark their landing forces located in Northern Norway in order to relocate them to the main theater of war in France. The German mountain troops occupied Narvik again on June 8th.

The Mountain Infantry Regiment 138 had also been divided into several squadrons for the occupation of Norway. The regiment's destination was the city of Trondheim . The heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and four destroyers served as transport units . After the mountain troops occupied the coastal fortifications, the city of Trondheim, the airport and a military training area, British troops also landed here. Together with units of the 2nd Mountain Division, the regiment then took action against the Allied troops and forced them to retreat. Individual companies of the regiment were then relocated to Narvik by air as reinforcements, while other parts of the regiment and larger units of the 2nd Mountain Division were set on the road by land ("Operation Buffalo"). In addition to the British forces, the nature of this project presented enormous problems. After the Allied troops had been withdrawn due to developments in France, a small group of mountain troops of the 2nd Mountain Division symbolically continued the march and reached Narvik on June 13, 1940 by land.

The A-Staffel (hawser and regimental units) of Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 was used for the reorganization of the Jg.Rgt. 141 used. From June 1, 1940, this Mountain Infantry Regiment belonged to the 6th Mountain Division, which was being set up at the Heuberg military training area . As a further unit, the reconnaissance department 112 joined the new mountain division.

The cessation of fighting against the Western Allies began a period of relative calm for the division. The units now took on the task of an occupying force. In the course of 1941, the 3rd Mountain Division and the 2nd GD were relocated to Northern Norway in the Kirkenes area by June , in order to be part of the XIX. Gebirgs-Korps (Mountain Corps "Norway") to be deployed for the war against the Soviet Union .

During this period of calm, the leadership of the division changed twice. Colonel Julius Ringel took over the 3rd Mountain Division on June 14, 1940 from Lieutenant General Eduard Dietl, who was appointed Commanding General of the Mountain Corps Norway. On October 23, Ringel passed the leadership of the division on to Major General Hans Kreysing , who was to lead it for the next three years.

- Consumption by the National Socialist propaganda

The peculiarities of the Narvik operation, such as the exposed location of the theater of war, the military success despite the unfavorable balance of power, but also the cooperation between the mountain troops, the navy and the air force, quickly led to the Nazi propaganda taking over those involved .

The subject of Narvik was covered by many newspapers throughout the Reich in 1940. The "Ostmärkische Gebirgsjäger" played a special role in publications like I am proud of my mountain hunters (in the eye-catcher of November 1, 1940) or mountain hunters crossed the Arctic Circle. Defeated Ostmärker in their element (in Deutsche Zeitung in Norway on June 8, 1940). In this way, the German press was able to refute the argument of enemy propaganda that the Austrians would only fight under duress in the Wehrmacht.

In many representations, such as edelweiss, anchor and propeller - symbolic unity in the defensive battle of Narvik , the cooperation between mountain troops, navy and air force was also referred to and at the same time pointed to the cooperation of the German tribes, whereby the mountain fighters for the alpine population and the navy symbolized the representatives of the north German coastal residents.

In this light, the foundation of the so-called Narvik shield can be seen, which symbolizes the three Wehrmacht parts in the form of an edelweiss, an anchor and a propeller. 2338 members of the 3rd Mountain Division received this award.

Hitler personally handed the Narvik Shield to the commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, Eduard Dietl, on March 21, 1941. Dietl was also awarded the Knight's Cross on July 19, 1940 as the first soldier in the Wehrmacht . The successful Narvik operation, but also his proximity to National Socialism and his biography subsequently made him one of Hitler's favorite generals, although the dictator probably valued less his military ability than his popularity. For the propaganda, from which he was subsequently also appropriated, he was particularly interesting because of his closeness to the people.

- Effects on the integration process of Austrian members of the Wehrmacht

For the historian Thomas Grischany, the Narvik operation represented the most important milestone in the integration process of the former Austrian soldiers into the Wehrmacht. This process, which began in the course of the annexation of Austria in March 1938, suffered at the beginning from different perspectives, traditions and mentalities of Germans and Austrians. When the retraining of Austrian soldiers on German training principles and drill regulations began in June 1938 , prejudices such as sloppiness, unreliability and inefficiency that the German instructors who had been transferred to their new subordinates harbored against their new subordinates came to light. On the other hand, the German training, which often relied on physical exhaustion, was unfamiliar to many Austrians, while it was more likely to be accepted by German recruits. In addition, there were a number of integrative factors, such as getting to know each other through stationing, exercises or training, the belief in a common future in a Greater German Reich, and a common revisionism towards the decisions of the victorious powers of the First World War .

With the beginning of the fighting in 1939, a further important factor was the shared experience of exceptional situations, which in the first years of the war were favored by the successes achieved with relatively minor losses. The Narvik operation represented the absolute climax here because it led to an enormous increase in the self-confidence of Austrian soldiers in the Wehrmacht, also due to the propaganda presence of this topic.

Even Austrian veterans of the First World War found this military operation to be a belated satisfaction, as their self-worth often suffered during their own service from the disdain for Austrian soldiers by the German army, which was expressed by the designation Comrade Schnürschuh .

The attack on Murmansk in 1941

- Framework conditions and planning

The XIX, which consists of the 2nd and 3rd Mountain Division. Mountain Corps was supposed to occupy the Soviet supply port of Murmansk in the course of the attack on the Soviet Union . This attack operation was part of the Silberfuchs company, which also planned that two further German divisions about 250 kilometers further south near Salla should try the railway line ( Murmanbahn ) leading from Murmansk to the south , via which part of the supplies of the northern sea convoys transported into the interior were to interrupt.

The units of the 3rd Mountain Division were relocated to Northern Norway on the Finnish border under the code name Pilgrimage from April 1941 . Subsequently, they had the order to occupy the Finnish area south of Petsamo , in which nickel deposits were important for the German war economy . Only seven days later, according to the plans, the Finnish-Soviet border was to be crossed.

Thus, for the XIX. Gebirgs-Korps, in contrast to the other German divisions on the main front, was the element of surprise. The Red Army should know how to use this in the future and be able to move additional troop reserves from Murmansk to the endangered border region.

Another problem was the complete lack of roads in the future operational area. In the first days of the attack, numerous combat troops, for example the entire Mountain Jäger Regiment 139 of the 3rd Mountain Jäger Division, had to be deployed to build roads become.

Subsequently, in front hinterland for creating replenishment and withdrawal streets were also so-called bog soldiers from the Emsland camps used, as well as work slaves from field labor camps of the Wehrmacht. Police investigations after the Second World War showed that in 1942, when most units of the 3rd Mountain Division were already in Germany, sadistic treatment of prisoners by soldiers of the Wehrmacht and arbitrary shootings were on the agenda. Responsible for these camps was the former commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, Eduard Dietl, whose military area of responsibility included these facilities, which military lawyers also rated as Wehrmacht concentration camps . As testimony of a survivor after the war brought to light, Dietl announced prisoners of a death march that less than 10 percent of those affected would survive with the words "Gentlemen, whoever does not come with us" will have appropriate consequences.

- Execution and failure

After the last units of the 3rd Mountain Division had only reached their meeting room around the Norwegian town of Kirkenes on June 17, the troops of the XIX. Mountain Corps crossed the Norwegian-Finnish border on June 22nd. While the 2nd Mountain Division occupied the Finnish Petsamo area, the 3rd Mountain Division stood ready for the attack on June 24 in the area further south around Luostari (Operation Reindeer).

On June 29, one week after the start of the fighting against the Soviet Union, the first parts of the Mountain Infantry Regiment 138 crossed the Titowka , while the Mountain Pioneer Battalion 83 and the Mountain Infantry Regiment 139 were used to build roads in the hinterland. After a few hours it became apparent that a street supposedly drawn on the map did not exist. The 3rd Mountain Division was stopped and now pulled behind the right wing of the 2nd Mountain Division in the direction of the Liza River .

The Soviet 14th and 52nd Rifle Divisions, reinforced by artillery units, had meanwhile set up defense along the Liza. On the German side, the supply difficulties due to the difficult terrain meant that individual companies of the 138 Mountain Infantry Regiment could only cross the Liza on July 6th. The Red Army responded with violent local counter-attacks and landings of troops in the deep flank of the XIX. Mountain Army Corps. As a result, on the German side, the overpassed troops were ordered back to the west bank of the Liza.

On July 13th and 14th, the 2nd Mountain Division was supposed to restart the offensive, in whose formation the Mountain Infantry Regiment 139 fought temporarily. But this attempt also failed because of the violent counter-attacks by the Soviet defenders. Only a small bridgehead remained east of the Liza after the withdrawal of the German units on July 18.

After an infantry regiment and a regiment of the Waffen-SS reached the combat area as reinforcement in August, the XIX. Mountain Corps on September 7th made the last attempt to break through the Soviet positions before the start of the Arctic winter. After a few initial successes, the new reinforcement troops in particular suffered great losses, so that after renewed violent counter-attacks by the Red Army, all attack operations had to be stopped.

Thereupon Hitler personally decided that the offensive operation on Murmansk was to be stopped for this year and that the mountain troops would have to defend the area conquered so far. The 6th Mountain Division , which was approaching from Greece , was assigned this task, while the other two divisions were newly equipped.

- Consequences and evaluation

For most of the 3rd Mountain Division, the relocation meant the end of fighting in this theater of war, because the division returned to Germany, where it was partially reorganized. Previously, the units marched 700 kilometers through the arctic winter to be embarked for transport to Germany in mid-December.

The 3rd Mountain Division lost around 1,000 dead and 2,600 wounded in this attack operation, which practically failed after just a few days. The XIX. Mountain Corps was the first major German unit in the German-Soviet War that was unable to achieve its strategic goals due to the resistance of the Red Army. The reasons for this were, in addition to the defensive success of the Soviet Army, the extreme terrain conditions, the exposed location of the theater of war and the resulting supply problems.

During the fighting on the Liza front, there was some resentment among the German troops towards the higher German leadership and also towards the commanding general of the mountain corps, Eduard Dietl. The commander of the Mountain Jäger Battalion 139, Colonel Alois Windisch , even refused an order to attack as pointless and was then removed from his post by the commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, Lieutenant General Hans Kreysing .

Since the fighting took place in an area that was largely deserted, there were no excesses against the civilian population in this theater of war, as was very common on the main front of this war.

The whereabouts of the Mountain Jäger Regiment 139

The only units of the 3rd Mountain Division were the Mountain Jäger Regiment 139 and the I./Geb.Art.Reg. 112 in the theater of war. Initially subordinated to the 6th Mountain Division, both units became army troops on January 15, 1942. The artillery department was renamed Mountain Artillery Department 124 and remained with the regiment. On June 5, 1944, the name was changed to Gebirgsjäger-Brigade 139; The brigade was named Generaloberst Dietl in 1945.

The troops were subordinate to the division group "Kräutler", which was also called the 9th Mountain Division (North) .

Restructuring - winter 1942

On the Grafenwoehr Training Area refreshing or reclassified Division from January 1942nd

- Mountain Hunter Regiment 138

- Mountain Hunter Regiment 144

- Mountain Artillery Regiment 112

- Mountain tank destroyer division 95

- Mountain Engineer Battalion 83

- Mountain News Division 68

- Reconnaissance Squadron 83

- Divisional Resupply Force 68

The building Jg.Rgt. 144 arose out of levies from the two mountain infantry regiments of the 5th Mountain Division . In the case of reconnaissance squadron 83, which was expanded to form reconnaissance department 83 in 1944, there are different information in the literature as to when it was assigned to the division. In February, the 3rd Mountain Division and the 5th Mountain Division exchanged their tank destroyer divisions.

In the literature, the cycling battalion 68 is mentioned, which was set up as a replacement for the delivery of the reconnaissance department 122 to the 6th Mountain Division in Norway in 1940. It was assigned to the 3rd Mountain Division, but always remained independent. The battalion was later to join the 5th Mountain Division, but it remained in Lapland and was ultimately subordinated to the 6th Mountain Division.

As a replacement for the cycling battalion 68, the division received the cycling department 95 from the 5th Mountain Division, but this also remained in Norway and thus did not represent a reinforcement for the 3rd Mountain Division.

Another occupation force in Norway - summer 1942

After refreshment, the division was shipped to Kristiansand in April 1942 . The units moved to the Lillehammer - Hamar - Elverum area , where they remained as an occupation force until August 1942.

Operations with Army Group North - autumn 1942

In August 1942 the division was relocated by sea to the area of Army Group North in Hangö , the Finnish port that had to be leased to the Soviet Union after the winter war of 1939/40 . The units of the 3rd Mountain Division marched from there to the area of Mga near Leningrad in order to be subordinate to the 11th Army transported by Army Group South .

This German army was under its Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, after the victorious battle for Sevastopol, together with two of its army corps ( XXX. And LIV. ) And four of its infantry divisions ( 24th , 28th , 132nd and 170th , which in addition 72nd still planned was diverted on the transport to Army Group Center ) was transferred to Army Group North. There Manstein's army in Operation Northern Lights was supposed to make a decisive contribution to the final conquest of Leningrad. However, this plan was thwarted by a major Soviet offensive that began on August 19th and intensified on August 27th, from which the 1st Ladoga Battle developed.

From September 5th the division reached the front line of the 11th Army in the forests of Osnakovno and it was not until September 28th that the units of the 3rd Mountain Division were involved in the fighting. In the course of the fighting, the two mountain infantry regiments carried out the main strike against broken through and trapped Soviet units near Gaitolowo. In heavy fighting, these opposing formations were destroyed by October 1, 1942 and 2,500 prisoners were brought in. The Red Army also had about 4,000 fallen Red Army soldiers. After that, the division met again in the Mga room to be briefly refreshed there.

Use of Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 at Velikiye Luki

The 3rd Mountain Division was transported to the Velikije Luki area in mid-October , at the interface between the Army Groups North and Central. When the division began to be loaded onto transport trains a month later in order to move it to the Caucasus , the battle for Velikiye Luki developed on November 24th . In doing so, the Soviet troops succeeded in locking in about 7,000 men in the city, who in bulk belonged to Grenadier Regiment 277 of the 83rd Infantry Division . The Soviet armies advanced far into the hinterland before countermeasures could be initiated on the German side.

While more than half of the 3rd Mountain Division was already on its way south, the loading of the remaining units (Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 as well as the mass of the Artillery Regiment and the Engineer Battalion) was stopped due to the development of the situation and supplied to the German troops, which were supposed to clean up the Soviet invasion. First, the mountain troops were deployed in the Novosokolniki area against the Soviet units that had broken through. At Chernosjem, the 138ers managed to contain the break-in area and from there to advance on Jeschwitzy into the break-through area and on November 26th to take the villages of Mishutkinio and Waraksino. In the ensuing fighting, the regiment was in turn enclosed by Soviet troops and almost wiped out. Only remnants could fight back to the new German lines at the end of November. The regiment and its subordinate divisional units had suffered terrible losses in these battles with more than 826 killed, 2,436 wounded and 105 missing.

Use of Geb.Jg.Rgt. 144 at Millerowo

While the Jg.Rgt. 138 fought at the interface between Army Groups North and Center, the remaining units of the 3rd Mountain Division were around the Mountain Jäger Regiment 144 on the rail transport to Army Group A in the direction of the Caucasus, until finally all transport trains on December 21 were stopped and diverted towards Millerowo .

The reason for the interruption of this transport movement was the operation Saturn of the Red Army , started on December 16, against the Italian 8th Army and the Hollidt Army Detachment . With this offensive, the Soviet Army wanted to bring the entire southern wing ( 1st Panzer Army , 4th Panzer Army and 17th Army ) of the German Eastern Front to the collapse after it had encircled the German 6th Army near Stalingrad on November 22 as part of Operation Uranus . On the German side, as a direct consequence of the formation of the cauldron near Stalingrad, the 11th Army staff under General Field Marshal Manstein had been converted to Army Group Staff Don and moved to the hinterland of Stalingrad.

With Operation Saturn, the Red Army intended to conquer the vast hinterland of the German southern front in order to make all relief efforts for the Stalingrad pocket impossible. The Italian 8th Army, which in the summer of 1942 had been inserted as a security force into the increasingly lengthened front of Army Group South due to the offensive in the direction of Stalingrad and the Caucasus , was completely destroyed. In the hinterland of the Italian army was the city of Millerowo, which at that time housed large supply and fuel stores for the Wehrmacht and an airfield for the air force.

The city was captured on July 16 by units of the 23rd Panzer Division and the 71st Infantry Division as they marched towards Stalingrad and the Caucasus and then became not only an important logistics center, but also the location for the POW camp Dulag 125 has been expanded. In this transit camp, which was located in a depression ("Millerovskaya pit") outside the city during the summer months, tens of thousands of Soviet prisoners of war were housed under the most primitive conditions.

The first units of the 3rd Mountain Division reached Millerowo on December 18 and set up for all-round defense. On December 23, there were first skirmishes with the advancing armored spearheads of the Red Army. On December 24th, the attempt of the Soviet Army to penetrate the city from the northeast with tanks failed. In the next three weeks the building Jg.Rgt. 144 as well as splinter groups of other Wehrmacht units of units of the Soviet XVII. and XVIII. Panzer Corps as well as the 38th, 44th and 58th Guards Rifle Divisions included in the city. Despite material superiority, the elite Red Army associations did not succeed in taking the city. To the surprise of the enclosed German units, on January 14th they received the order to break out of the pocket in the direction of Donets . This began on the evening of the next day and after large parts of the city had already been destroyed by the previous fighting, further objects were blown up by the German troops in the course of the outbreak according to the scorched earth war statics .

In the next three days the regiment and its subordinate units fought their way back about 100 kilometers in a south-westerly direction to the Donets in the Voroshilovgrad area. The Red Army tries to prevent the German retreat through flank attacks and barriers, but the German troops managed to break through the Soviet army's barriers twice and after three days of losses they reached the improvised front on the Donets.

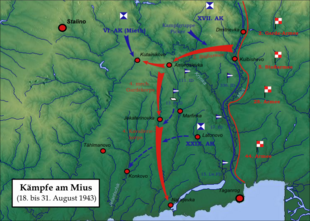

Fight in the Mius position

- Consolidation of the German southern front on the Mius

After the 3rd Mountain Division broke out of the Millerowo pocket and fought its way towards Voroshilovgrad, it defended its position here until the end of January without having any connection to a front in the west. In the south-east, however, it was connected to the severely battered 304th Infantry Division . This division was one of several units hastily thrown onto the eastern front that had previously served as occupation forces in the west. Due to the lack of experience with the conditions in Russia, these infantry divisions were completely overwhelmed and often suffered heavy losses in the first battles against the Red Army.

Between Slovyansk , about 150 kilometers from Voroshilovgrad, and Kharkov there was a 200-kilometer hole in the German front that had been created by the successes of the Red Army against the Hungarian 2nd Army and the Italian 8th Army. The Soviet Army tried to take advantage of this fact and sent mobile units, such as General Markian Popow's tank group , to the rear of the German units in order to try again to encircle the exposed German units far to the east. But just as Hitler overstrained and overestimated the forces of Army Group South in 1942, this also happened on the Soviet side. Without a sufficient supply of fuel and ammunition, parts of these pre-chased units stranded in the German hinterland. In the course of February they were gradually crushed by the SS Panzer Corps assembled near Kharkov and the 1st Panzer Army , which had been ordered back from the Caucasus . Through these and other operations , the Wehrmacht again succeeded in forming a closed front west of the 3rd Mountain Division, which in its course was based on the Donets .

Southeast of the 3rd Mountain Division, the units deployed there had been combined to form the Hollidt Army Division . After persistent negotiations, on February 6, Hitler finally allowed the withdrawal of these units to the Mius, which had already served as a German defensive position in the winter of 1941/42 after the battle for Rostov . The withdrawal of the Hollidt Army Division began on February 8 and was completed on February 17. The Red Army immediately followed suit with motorized units and the IV. Guard Mech Corps managed to cross the river on February 18 at Matveev Kurgan , about 110 kilometers southwest of Voroshilovgrad, and advance about 30 kilometers into the German hinterland. The lack of supplies but also the bad weather favored the German counter-attack, which was led by the only two German motorized divisions available in this area of the Eastern Front, the 23rd Panzer Division and the 16th Panzer Grenadier Division . By breaking up the Soviet units, the German Wehrmacht succeeded in stabilizing the Mius front in this section.

South of the 3rd Mountain Division, too, the VII Guards Cavalry Corps, a larger Soviet unit, had managed to break through to the west. After the corps was isolated, it attempted on February 24th to push through to the Soviet lines in the east. It was smashed by a paratrooper battalion subordinate to the mountain division.

After the front along the Mius had stabilized , also helped by the onset of the Rasputitsa , a period of relative calm began for both the German and the Soviet units. This was used on both sides to put the associations in order and fill gaps with replacement teams. While the Red Army was massively strengthened with fresh troop contingents, the 3rd Mountain Division received a significant increase in combat power by adding the units deployed at Velikiye Luki. Between March 15 and 28, the Gebirgs-Jäger-Regiment 138, the Gebirgs-Pionier-Battalion 83, the Panzer-Jäger-Department 48 and large parts of the Gebirgs-Jäger-Artillery-Regiment 112 were transported from the central section of the Eastern Front more than 40 transport trains.

The 3rd Mountain Division belonged to the IV Army Corps during the fighting in spring 1943 . It was considered the most powerful division of the Hollidt Army Division, which was renamed the new 6th Army on March 6, 1943, while its neighbors, the 335th Infantry Division to the west and the 304th Infantry Division to the southeast , suffered heavy losses in the winter fighting due to their inexperience the Soviet theater of war had to accept. In the south the XVII. Army Corps with infantry divisions 302 , 306 and 294 . The XXIX followed farthest south . Army Corps with the 336th , 17th and 111th Infantry Divisions and the 15th Air Force Field Division . The only reserve was the 16th Panzer Grenadier Division, which was the only unit of the 6th Army to have tanks. The opponent of these German units was the southern front under the command of Fyodor Tolbuchin .

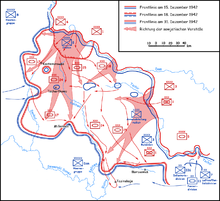

- Donets-Mius offensive

On July 5, the last major German offensive campaign in the German-Soviet war began with the Citadel company near Kursk . In order to relieve the Soviet units in the Kursk Bogen and to lure the German intervention reserves away from this section of the front, the Soviet high command ordered the implementation of the Donets-Mius offensive . Contrary to the usual Soviet military doctrine, the preparations for this offensive were not camouflaged, but carried out as conspicuously as possible in order to provoke German countermeasures such as moving the mobile reserves. So it was the German radio reconnaissance soon succeeded in the focus of the deployment of the Soviet troops before the 17th. Identify Army Corps.

In order to fragment the German defense, the Soviet southern front carried out a series of diversionary attacks, whereby it was careful to always carry out attacks at the seams between two divisions or two army corps. In addition, there were regimental attacks in several places on the front to confuse the German defenders.

The main strike should be the 5th shock army and the 2nd guard army at Kuibyshevo in the area of the XVII. Army Corps on the border between the 302nd and 294th Infantry Divisions. In addition to the various strong regimental attacks, two larger diversionary attacks on the borders of the XVII. Army Corps. In the north, at the interface with the IV Army Corps, three rifle divisions and a tank brigade attacked. In the south at the interface to the XXIX. Army Corps even had seven rifle divisions on the southern front. While the heavy regimental attacks were not a big problem for the German defense, the Soviet units at the borders of the XVII. Army Corps deep break-ins. The 6th Army was prepared for this situation and was able to solve these crises within the corps borders with the use of local reserves.

The defensive position of the 3rd Mountain Division was attacked on July 17th by parts of the Soviet 91st Rifle Division and four companies of prisoners. These were forced by NKVD blocking troops to storm the German positions and to repeat the attack until none of them lived. After repelling the attack, the German units counted at least 800 dead Soviet soldiers in front of their own positions, only 25 soldiers were taken prisoners of war. During the course of the day, the division received the order to march south to the 304th Infantry Division, where the Red Army was on the border with the XVII. Army Corps had managed to break deeply into the German front. One battalion each from the two mountain hunter regiments, the reconnaissance division, a division of the mountain artillery regiment and other support troops participated in the cleaning up of the Soviet intrusion into the so-called Redkina Gorge over the next five days. In very loss-making battles, in which the Red Army lost around 2,000 dead in the area of the mountain hunter units deployed, the losses of the mountain hunters with 650 men were as much as the losses of the entire division in the last four months.

Since the German radio reconnaissance had clearly identified the focus of the Soviet deployment near Kuibyshevo, the 23rd Panzer Division was brought in from the area of the 1st Panzer Army as a precaution. The Red Army led this main strike with far superior forces, so that neither the 23rd Panzer Division nor the 16th Panzer Grenadier Division were able to clear the deep incursion into the German front that had formed soon after the start of the attack. The German troops therefore had to wait for the arrival of the II SS Panzer Corps before they could go back on the offensive at the end of July. By August 2, the units of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS succeeded in pushing the Red Army back over the Mius or smashing larger troop contingents on the west side of the river after fighting with very heavy losses for both sides. The 3rd Mountain Division also had to deploy two units. The field replacement battalion fought as part of an association of alarm units of the XVII. Army corps in the northern area of the burglary area. The III. Battalion of the 138 Mountain Jäger Regiment, which had previously suffered great losses in the Redkina Gorge, was then also deployed in the Kuibyshevo combat area as part of the 16th Panzer Grenadier Division. When he returned to the main division on August 17, only a sixth of the men who had been alerted on July 17 were still alive or still uninjured.

In the two-week battle, the 6th Army was able to bring in 18,000 prisoners of war and cause the units of the Red Army to lose several times that number. Strategically, however, the southern front had achieved its goals. It was not only able to lure the II SS Panzer Corps away from the area around Kharkov , where it was then missing in the initial phase of the Belgorod-Kharkov operation , but also inflict losses of over 2,500 men. The 6th Army itself lost about 21,000 men, the loss of which was all the more serious because the German infantry divisions in this section of the Eastern Front were already very weak.

- Start of the Donets Basin operation

After the completion of the Donets-Mius operation, the 6th Army was immediately withdrawn not only from the II SS Panzer Corps, which was urgently needed in the Kharkov area, but also the other two motorized units, the 23rd Panzer Division and the 16th Panzer Grenadier Division, had to be handed over to the adjoining 1st Panzer Army to the west in order to repel the Donets Basin operation begun on August 13 from the south-western front.

While the losses of the 6th Army were not compensated with a few exceptions and all motorized units were taken away from it, the Soviet side largely replenished the decimated units of the southern front within just two weeks. Unlike in mid-July, this time everything was done to disguise the deployment of these new forces. The 6th Army was largely in the dark when, on August 18, the southern front again went on the offensive with superior forces in the area of the 294th Infantry Division, which had been weakened in the previous battles and made a ten-kilometer break in the first attempt.

The army command tried to mobilize the last reserves in order to use them under the leadership of the new commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, Major General Egbert Picker , from the north against the Soviet break-in point. The forces at his disposal were inadequate with five battalions, six batteries, an assault gun battery and two tank destroyer companies, with 2,000 men from the 3rd Mountain Division. This improvised combat group succeeded in shooting down 43 Soviet tanks on August 20 and almost closed the gap in the front, but the next day the Soviet IV Guard Mech Corps, which had already broken through, turned and attacked the combat group behind them. The Red Army again lost more than 40 tanks, but the German attempt to close the gap in the front had failed. In the days that followed, the Picker combat group fell into the pull of the German retreat and was almost completely wiped out. Fewer than 200 of the mountain fighters who entered on August 18, 2000, returned to the division in September.

After fighting off the counterattack by Kampfgruppe Picker, the Soviet units succeeded in widening the gap in the front up to nine kilometers. The units of the Red Army then turned south to the XXIX, which consisted of four divisions. Army Corps, which covered the right section of the front of the 6th Army, to encircle.

After the heavily weakened 9th Panzer Division and parts of the 13th Panzer Division from the Crimea had been brought in, these divisions had the task of carrying out the XXIX. To terrorize army corps. As an additional support measure, the commanding general of the IV Army Corps, General of the Infantry Friedrich Mieth , was ordered to assemble more troops for a counterattack. These comprised the bulk of the 3rd Mountain Division and the 17th Panzer Division , which had been brought in from Donets by the 1st Panzer Army. With these troops General Mieth attacked from August 28th to the southeast, to the XXIX. Army Corps to facilitate the escape from the pocket. These counter-attacks led to the fact that the Red Army had to loosen the containment ring, so that the units of the XXIX. Army corps managed to make their way west, albeit with great losses.

- Retreat to the Dnieper

At a higher level, General Field Marshal Erich von Manstein had been wrestling with Hitler for days (August 27), who even flew to the headquarters of Army Group South in Vinnitsa to be able to withdraw the permit, the 6th Army and the 1st Panzer Army far to the west . Hitler fought vehemently against this proposal, because he did not want the Donets Basin , which from his point of view was economically warlike, with its rich coal reserves to be lost to the Red Army. Due to the development of the situation at XXIX. Army Corps gave Manstein the withdrawal of the front to a position east of Stalino without authorization . In further discussions with Hitler on September 4 and on September 8, when Hitler visited the front again at the headquarters of Army Group South in Zaporozhye , the dictator finally gave in. Manstein immediately ordered the gradual withdrawal of the front as far as the Dnieper .

For the 3rd Mountain Division, this order now had the effect that it could withdraw to the west in several stages:

- On September 9th, she moved into what is known as the "lizard" position.

- On September 13, the intermediate position in the section Antonovka - Zelenoplje - Ssloadko - Vodnaja was reached.

- On September 14th the division was on the west bank of the Gaitschul.

- On September 16, she stood on the west bank of the Konka.

- In the period from September 20th to October 9th she was in the prepared "Wotan" position. Then the pressure from the Red Army became so great that the front began to move again.

- By November 14, 1943, the division was pushed back into the Nikopol bridgehead on the Dnieper.

During the defense of the Wotan position, the division fought southeast of Zaporozhye in a village with the German name Heidelberg . Its northern neighbor was the 17th Panzer Division, its southern neighbor the 17th Infantry Division . In the fighting from September 26th to 30th, the two weakened mountain hunter regiments of the division faced a total of five Soviet rifle divisions and two tank brigades with around 100 tanks. In the four days that followed, with the help of reserves brought in by other infantry divisions, all attacks by the Red Army, including a mass attack by around 18,000 Soviet infantrymen on September 30, could be repulsed before the final move into the Nikopol bridgehead.

Defense of the Nikopol bridgehead

To the north of the 6th Army, the Soviet units in the area of the 1st Panzer Army had already crossed the Dnepr at the end of October, while the 3rd Mountain Division was defending the Nikopol bridgehead as part of the IV Army Corps. The divisional headquarters were temporarily located in Dnjeprovka, while the mountain troops defense area ran southeast of it. Left neighbor was the 302nd Infantry Division , right neighbor the 17th Infantry Division. The corps command post was in Nikopol to the northwest.

The bridgehead itself was not attacked until November 20. In the more than ten days of fighting, the 24th Panzer Division, held in readiness, had to intervene. In cooperation with this East Prussian Panzer Division, the 3rd Mountain Division succeeded in repelling all attacks by the Red Army with heavy losses. At the end of the battle, 146 Soviet tanks shot down and 2,000 Red Army soldiers dead were counted in front of the mountain division. Another major attack took place between December 19 and Christmas 1943. Here, too, the deployment of the 24th Panzer Division was necessary, with whose help the hard-pressed mountain troops managed to hold their positions or to recapture them.

A member of the 24th Panzer Division described the situation of the position divisions in the bridgehead in his war memories:

“... we now know how well we are as an alarm unit compared to the position troops. They have been living in the filthy holes of the HKL for weeks and months . Because the frost set in late that year, some of the holes were muddy up to the ankles. And if the Soviets rolled over them with their tanks, they wouldn't even have a chance to get out of the thick mud and save themselves quickly enough. How often have we cursed at them when we had to deploy again because the enemy in the HKL had breached their positions. But when we realized what inadequate weapons and what little support from heavy weapons, especially the infantry, had to hold their positions, we only felt sorry for the poor devils. "

Evacuation of the Nikopol bridgehead and retreat towards Romania

The Red Army resumed its attacks on the Nikopol bridgehead in early February 1944 ( Nikopol-Krywyj Riher operation ). Since the Soviet divisions had crossed the Dnieper both in the north and in the deep south-western flank, the scheduled evacuation of the bridgehead began in the first half of February. The retreat to the west was extremely difficult as days of rain had made the roads impassable. Mud and mud hindered the return of heavy weapons, so that above all the artillery guns had to be blown up.

During this retreat, the 3rd Mountain Division was encircled for the first time, but was able to break out to Krasnyj near Nikolayev by February 12. The OKH's situation map of February 29, 1944 showed the tense situation of Army Group South as a snapshot. The mountain division was then in a room northwest of the former bridgehead area in the center of the defense line of the XXIX. Army Corps to be found. In the period from February 13th to 27th, the units of the mountain division withdrew to the Ingulez , always beset by the Red Army . Leaning against the river, the front was made again and the following Soviet units opposed vigorous resistance until March 7, before the withdrawal had to be commenced due to a renewed outflanking by the Red Army ( Bereznegowatoje-Snigiriov operation ). The breakthrough succeeded again, with the Southern Bug being reached by March 18th.

This was followed by a longer stay in defensive positions on the west bank of the bow in the Dmitrievka area. The mountain hunters had to take part in the period from March 18th to 27th as part of the XXIX. Army Corps to seal off a Red Army bridgehead that it had formed on the western bank of the Bug. Northern neighbor was about the 97th Jäger Division , the southern neighbor to a battle group fused 335th Infantry Division .

On March 28th the front started moving again ( Odessa operation ). The 3rd Mountain Division and its neighboring divisions defending on the Bug withdrew about 10 to 20 kilometers per day to the west for the next few days (Company Alphabet ). In total, the mountain troops had to walk 300 kilometers in combat conditions over the next twelve days. Attempts were made again and again to offer brief resistance in defensive positions. These resistance lines were marked with letters and were defended for a few hours: B line (March 28/29), C line (March 29/30), D line (March 31), E line (March 1st) April), F line (April 2nd). On April 3rd, pant production - also known as the G line - was reached.

On April 4, the Soviet units at Konstantinovka, the 3rd Mountain Division and parts of the 17th Infantry Division , the 258th Infantry Division , the 294th Infantry Division , the 302nd Infantry Division and the 335 succeeded . To encircle Infantry Division. In the next few days, the remaining formations, which were combined to form the "Wittmann Group" under the leadership of the commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, Lieutenant General August Wittmann, managed to reach the front on the Dniester, which had been poorly built up by other German units .

In these retreat battles the division suffered the heaviest losses, so the 138 Mountain Jäger Regiment had a nominal strength of around 3,000 men and only had around 1,000. With the Mountain Artillery Regiment 112, only eight of the former 20 guns reached the rescue front. In some divisions of the 6th Army the officer and non-commissioned officer losses during this retreat amounted to up to 80 percent.

Fighting in Romania in the spring of 1944

After the division's arrival in Romania, the commanding XXIX. Army Corps admitted that they could reorganize in the rear of the front.

However, as early as April 17th, about half of the division's combat troops had to form combat group Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 to be used as a "fire brigade" on various front sections. By the time it was reunified with the rest of the division on May 28, this combat group suffered losses of around 800 men.

At the end of April, the 3rd Mountain Division took over an approximately ten kilometer long section of the front southeast of Slobozia near Talmaz. Since there was only minor, local fighting in this area of the front at that time, the replacement of 2500 men that had arrived could be incorporated into the units of the division.

On May 22nd, the division was withdrawn from its previous position. She had to march towards the Eastern Carpathians and was now deployed in an area for which she had been trained and also equipped.

When the troops were relieved , an incident occurred with the close-knit units of the Romanian army , which escalated to such an extent that a lieutenant of the mountain hunters fired on Romanian soldiers, killing two Romanians. When the division commander, Lieutenant General August Wittmann, opposed the furious Commander in Chief of what was now Army Group South Ukraine , Colonel General Ferdinand Schörner , and defended his men, he was recommended to go on vacation. The division was withdrawn from him and Lieutenant General Paul Klatt was subsequently appointed to lead the division.

Fighting in the Eastern Carpathians summer and autumn 1944

On May 28, the now reunited with the Mountain Jäger Regiment 138 reached the new operational area, where they were the XVII. Army Corps was under. The OKH's location map of August 19, 1944 showed this army corps leaning against the eastern slope of the Carpathian Mountains in the area south of Chernivtsi, approximately at the height of Suceava . The 3rd Mountain Division, together with subordinate Romanian units, had to secure a 40-kilometer section of the front.

The opposing enemy formations were relatively weak, so that the division was able to recover in the trench warfare that followed. Newly arriving march battalions filled the ranks of the units and finally brought the 3rd Mountain Division to full strength.

While it was relatively quiet in its own section, the front length had to be more than doubled from 40 to 95 kilometers from mid-July because the Red Army achieved an operational breakthrough in the course of the Lviv-Sandomierz operation near Brody and the right-hand neighbor, the 8th Jäger Division , was withdrawn to the northwest.

As a sign of the further military development in the south of the Eastern Front, on August 19 the Red Army launched local attacks against the front of the 3rd Mountain Division. The Soviets were able to break into large areas of land defended by Romanian troops. By using the few reserves, the division leadership was able to stop the enemy attacks and restore the old front line by August 24th.

In the meantime the situation in Romania had changed fundamentally. Operation Jassy-Kishinev was launched by the Red Army on August 20, and after a few days it led to the destruction of the 6th Army. The subsequent coup in Romania ultimately led to the Romanian army switching sides.

These developments did not remain without effects on the divisions of the XVII. Army Corps. On the night of August 24th, the 3rd Mountain Division lost about 300 men to Romanian units who suddenly showed themselves hostile. In this chaos it took two days for the division to regain order. In the course of this, there were also further skirmishes with previously befriended Romanian units.

From the end of August the Red Army tried to get offensive in the Carpathian Mountains and to gain access to the mountains. The 3rd Mountain Division, however, was able to stabilize the front along the ridges of the Bistritz Valley and hold it against the advancing Soviets until September 6th. In the meantime the Red Army had managed to outstrip the units of the 3rd Mountain Division further south. The 3rd Mountain Division, which had to surrender numerous units to other superior positions, was now faced with an eleven-day retreat into the Mureș section. While the linear distance to this area is only about 70 kilometers, the units had to torture their way west over mountain passes and valleys almost three times, constantly threatened by Soviet units or dangerous flanking from the south.

In the Mures part there was heavy fighting between September 24th and 30th with two regiments of the Red Army who intended to block the way back for the German units. The 3rd Mountain Division succeeded in encircling and largely smashing the two Soviet regiments. The general development of the situation led to the fact that from October 8th, individual parts of the 3rd Mountain Division from Transylvania began to march westwards, while Adolf Hitler did not issue the final order to clear this area until October 17th . On October 21, the division had to endure heavy fighting 20 kilometers southeast of Satu Mare , before crossing the Hungarian border in the evening and 52 hours later reaching the area south of Nyíregyháza .

Fighting in Hungary in late autumn and winter 1944

- Historical background

Hungary , on whose territory the fronts moved in 1944, was one of Germany's closest allies in World War II. Driven by the intention to revise the consequences of the Treaty of Trianon , in which the country had lost around 70 percent of its old territory, it formed an early bond with the German Reich and was able to separate some of the 1920s in several stages in the slipstream of German expansion Regaining territories (1938: First Vienna arbitration , 1939: Slovak-Hungarian War , 1940: Second Vienna arbitration , 1941: Balkan campaign ).

In order to keep Hitler's favor, Hungary also took part in the war against the Soviet Union. In 1941 a "fast corps" consisting of 30,000 men was deployed, after the great German losses in the winter of 1941/42, the 2nd Hungarian Army with 200,000 soldiers and a further 50,000 auxiliary troops moved to the Soviet Union in April 1942 to protect the German flank Advance to be used on Stalingrad. In the course of the operations around the Battle of Stalingrad, this Hungarian army was destroyed in a few weeks by the technically superior Soviet troops. Of the 250,000 men in 2nd Army, only about 40,000 returned after the war.

On March 19, 1944, the Wehrmacht occupied Hungary ( "Operation Margarethe" ) because it was expected that the alliance partner would break away due to the development of the military situation on the Eastern Front. In the course of the occupation, the Eichmann Special Task Force was set up, which organized the Holocaust against the Hungarian Jews in the following months . After the Jews in the Hungarian province had been ghettoized , the deportation began on May 15, mainly to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp , until the deportations ceased in July due to international protests. Tens of thousands more people were killed in the Battle of Budapest and the construction of the Southeast Wall . In total, only 260,000 of the 825,000 Jews who lived in Hungary during the Second World War survived.

- Battle of Nyíregyháza (October 21-26, 1944), Soviet war crimes

While the 3rd Mountain Division and with it large parts of the German 8th and the Hungarian 1st and 2nd Armies were still in Transylvania , the Red Army tried to cut off these units about 100 kilometers to the west as part of the Debrecen operation . To this end, north of Debrecen , they deployed three corps (the XXIII Panzer Corps and the IV and V Guard Cavalry Corps ) of the mechanized cavalry group of the 4th Ukrainian Front under the leadership of General Issa Pliyev to advance north . The city of Nyíregyháza was occupied on October 22nd , whereby the connection between the 8th Army in Romania and the 6th Army in Hungary was lost. After this direction of attack by the Red Army had been emerging for a few days, the III. Panzer Corps with the 1st , 13th and 23rd Panzer Divisions pulled out of a less endangered section of the front and relocated to the north.

While the 13th and 1st Panzer Divisions supported the advance of III. Panzer Corps to the south, the 23rd Panzer Division reached Nagykálló, southeast of Nyíregyháza, as early as October 22nd , thus severing the supply lines of the three Soviet corps. These tried to break through the enclosure from the north, while other Soviet units launched attacks from the south to break open the pocket. 36 hours later, in the morning hours of October 24th, the foremost parts of the 3rd Mountain Division approaching from Romania arrived in Nagykálló.

On October 26th, the German troops attacked in turn. The two regiments and the engineer battalion of the 3rd Mountain Division advanced from Nagykálló in a north-westerly direction towards Nyíregyháza, while the 23rd Panzer Division advanced from the south-west towards the city. After heavy fighting, large parts of the three enclosed Soviet corps were broken up. In a report dated October 27, the 3rd Mountain Division reported to a superior agency that six tanks had been destroyed, 852 enemy dead and only 34 prisoners. In the division history of the 23rd Panzer Division there were no exact figures for this event, only for the period from September 28 to October 28 the losses of the Red Army were given as 3,500 dead and 707 prisoners of war. In this light, the information on the losses of the three Soviet corps, which one finds in some books about this battle, with 632 tanks and 25,000 men (6,662 dead) seems to be far too high.

What is undisputed, however, is that the Red Army in and around Nyíregyháza committed a number of war crimes , primarily against the female population. While only one sentence can be found in the division history of the 23rd Panzer Division, more space has been devoted to this topic in the division history of the 3rd Mountain Division. It was made from a daily report to the superior Hungarian IX. Army corps of October 26, 1944, in which some particularly blatant cases of rape, some resulting in death, were reported to the commanding corps. The Hungarian historian Krisztián Ungváry confirmed these occurrences in the course of his research. He went on to explain that members of the Guards Cavalry Corps raped all inmates of a psychiatric clinic in Nagykálló and that German and Hungarian soldiers had to protect Red Army soldiers captured from revenge by resentful residents in the areas that were recaptured at short notice. The American author Samuel W. Mitcham , who referred to statements made by the Commander-in-Chief of Army Group South, Colonel-General Johannes Frießner , when describing further shocking details, further asserted that these war crimes were the will of the Wehrmacht to resist the Red Army, significantly influenced in order to avoid similar scenes in Germany.

From a military point of view, this short-term, local German success enabled the orderly withdrawal of the German-Hungarian units from Romania. The 3rd Mountain Division stayed two days in Nyíregyháza, which was finally occupied by the Red Army on October 30th, and withdrew gradually towards Tisza .

- Fights on the Tisza and Miskolc

At the beginning of November most of the units of the 3rd Mountain Division crossed the Tisza and took over a section of the front about 50 kilometers south-east of the industrial city of Miskolc . This lay, apart from two small bridgeheads at Polgár and Tiszadob , on the west bank of the river.

The industrial city of Miskolc was home to arms factories and arsenals for the Hungarian army. It also represented a railway junction that was attacked several times by the Allied bomber fleets. On June 2, 1944, units of the 304th Bombardment Wing (including the 455th Bombardment Group and 459th Bombardment Group) bombed the station, but many bombs fell into the residential area, killing 206 people and injuring 420. Further attacks by the Royal Air Force and the Fifteenth Air Force took place on the night of August 22nd to 23rd and August 28th, 1944. The city was also a scene of the Holocaust against the Hungarian Jews. In April 1944, a ghetto was created in Miskolc in which Jews from the city and the surrounding area were crammed together. Between June 12 and 15, 1944, 15,464 people were deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp on three transport trains.

In the first week of November an uprising broke out among the approximately 20,000 armaments workers in Miskolc, which a little later, at least in part, was suppressed by Wehrmacht troops. An unknown number of workers continued to fight and fought in the second half of November, when the 3rd Mountain Division had withdrawn to Miskolc, with the Mountain Jäger Regiment 144 which had moved into the industrial area.

During November the Red Army attacked in the section of the 3rd Mountain Division with a total of six rifle divisions, one cavalry division and two mechanized brigades, with the aim of using this operation to secure the encirclement of the capital Budapest from the north. The superiority of the Soviet troops meant that the neighboring units of the mountain division also suffered great losses, which threatened to bypass Miskolc in the north and west. The 3rd Mountain Division was therefore ordered to withdraw from the industrial city in the direction of Slovakia. In the division history is noted with a bitter undertone:

"The ringing of bells and music heralded the arrival of their" liberators "."

Retreat through Slovakia

After Miskolc was surrendered by the German troops, the 3rd Mountain Division slowly withdrew to the north-west of Slovakia , to the headwaters of the Sajó and Rimava rivers, with hesitant resistance . The Red Army tried for its part with eight divisions to gain access to the headwaters of the Sajós. This resulted in heavy fighting between December 10th and 25th, which often resulted in hand-to-hand combat, in extreme terrain.

The withdrawal to Slovakia led to a change in the subordination of the 3rd Mountain Division. While in Hungary at times the XXIX. Army Corps, which belonged to the 8th Army, was placed under the XVII in January. Army Corps, which was part of the 1st Panzer Army .

Another difference to Hungary were the partisans in Slovakia, because the Slovak National Uprising took place there between August 29 and October 28, 1944 . The center of the uprising, which was supported by parts of the Slovak army and the partisan movement, was the city of Banská Bystrica in central Slovakia. The uprising had developed a military clout that was initially underestimated by the German authorities. After a few initial successes, the suppression of the uprising stagnated in September by the German troops that had invaded Slovakia on August 29. The Slovaks managed to stop the German advance into the heartland of the uprising. In a second phase, which began in mid-October, the current German occupiers were able to put down the insurrection movement through massive deployment of various new troops, including SS units such as the notorious SS Brigade Dirlewanger . On October 28, the Slovak general Rudolf Viest accepted the defeat and ordered the surviving soldiers to give up the regular resistance and instead to continue armed struggle as partisans in the mountains. The Slovak partisan movement was heavily dominated by Soviet partisans from mid-1944 onwards, as an agreement in May 1944 between Klement Gottwald , chairman of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia , and Nikita Khrushchev , then general secretary of the Ukrainian communists, agreed that the partisans would join forces in Czechoslovakia subordinated to the Ukrainian partisan movement led from Kiev .

In this light, a report from the 3rd Mountain Division to the superior service dated January 3, 1945 was seen, in which, after a battle with partisans, they were described with Slovak uniforms and Russian leaders. The partisans preferred to cause unrest in the hinterland of the mountain division by ambushing transports or mining supply roads. There was a major battle with partisan units on January 29th when they were able to inflict heavy losses on a battalion of the Mountain Jäger Regiment 138 near Brezno . At this point in time the 3rd Mountain Division was already in the Hron Valley, into which it found its way from January 22nd to 27th, hard pressed by the Soviet 42nd Guards Rifle Division, the 133rd and 240th Rifle Division and a Romanian cavalry division.

On February 10th, the 3rd Mountain Division began their retreat, which led them through the center of the Slovak National Uprising, Banská Bystrica. The destination was the Waag Valley, where she took on a security job in the High Tatras and Low Tatras . Six years earlier, this area had been the division's staging area for the attack on Poland. With the retreat into the Waag Valley, the subordination changed again, the now superior XXXXIX. Mountain Army Corps remained subordinate to the end of the war. During this time, the division received extensive replacement contingents, including a complete mountain hunter regiment.

By the beginning of March, the units of the 3rd Mountain Division gradually left Slovakia by crossing the Beskids towards the north via the Jablunka Pass .

Fight in Katowice Governorate

After crossing the Beskids, the 3rd Mountain Division was in the administrative district of Katowice , an area of around 10,500 km² that had been incorporated into the province of Upper Silesia in violation of international law after the attack on Poland . In 1939, about 2.43 million people lived in this administrative district, of which 930,000 were Poles, 1.08 million Germans and, depending on the source, between 90,000 and 120,000 Jews . The Holocaust , which began for the people here with kidnappings as part of the Nisko Plan , at least 85,000 people were killed by 1945. In addition to the persecution of Jews, there were also "resettlement campaigns" ( Saybusch campaign in December 1940 with 17,000 displaced persons and "Buchenland campaign" in winter 1940/41 with 63,000 people) in which Polish farmers had to vacate their farms and instead 38,000 ethnic Germans from the Bukovina were settled. Despite these evictions, about 85 percent of the population of the administrative district was confirmed by the authorities to belong to groups 1 to 3 of the German People's List , although this was also done under the assumption that the people were enormously important as workers for the war economy in the Upper Silesian industrial area. Any resettlement was therefore postponed until the post-war period.

Against this background, a passage in the history of the division can be seen that was not otherwise detailed:

“The connection with the government in Teschen was close. She strengthened herself with us and gained new confidence. Deficiencies identified by us, which were caused by the SD and came to our knowledge, were dealt with in an objective manner. "

From a military point of view, the 3rd Mountain Division had to occupy a front about 50 kilometers long, which stretched from Jablunkov to Freistadt . Despite the precarious overall situation for the Wehrmacht in this phase of the Second World War, things remained relatively calm at the front of the mountain division. On 10 and 15 March took place in a neighboring division section to an attack of the Red Army, which the provision of self-propelled guns of the tank destroyer - Department necessitated the division.

After the Red Army captured Bratislava in the course of the Bratislava-Brno operation on April 4, this also had an impact on the 3rd Mountain Division, which withdrew its troops behind the Vistula . In the course of April, the division moved further west in stages until it finally left the area of the Katowice administrative district in early May.

Surrender in the Czech Republic

Due to the general situation, the 3rd Mountain Division began a westward shift on April 20, which went into a retreat from May 1, which the division via Frýdek-Místek , Nový Jičín , Lipník nad Bečvou to the Olomouc area . The mountain hunters always had to defend themselves against the attacking Soviet units.

The foremost parts of the division, including the motorized units, reached the Deutsch-Brod area , where they capitulated to the Red Army. Many soldiers tried individually or in small groups to reach the German border or the units of the US Army in order to avoid captivity in the Soviet Union. Most of them didn't succeed. The last commander of the 3rd Mountain Division, Lieutenant General Paul Klatt , was also taken prisoner of war after the end of the war, from which he was only released in 1955.

people

Commanders

- Major General / Lieutenant General Eduard Dietl - April 1, 1938 to June 14, 1940

- Lieutenant General Julius Ringel - June 14 to October 23, 1940

- Major General / Lieutenant General Hans Kreysing - October 23, 1940 to August 8, 1943

- Colonel Hans Mönch - August 8-10, 1943.

- Major General Egbert Picker - August 10-26, 1943

- Colonel i. G. Siegfried Rasp - August 26th to September 10th 1943 (entrusted with the deputy leadership)

- Lieutenant General Egbert Picker - September 10-29, 1943

- Major General / Lieutenant General August Wittmann - October 1, 1943 to May 28, 1944

- Colonel Hans Kreppel - May 28, 1944 to July 3, 1944

- Major General / Lieutenant General Paul Klatt - July 3, 1944 until surrender

Excellent members of the division

Bearer of the oak leaves for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The following members of the division were awarded the Oak Leaves for the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross :

| Rank | Surname | unit | Award number | Award date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant General | Eduard Dietl | Commander 3rd GebDiv | 1 | July 19, 1940 |

| Lieutenant General | Hans Kreysing | Commander 3rd GebDiv | 183 | January 20, 1943 |

| Lieutenant colonel | Albert Graf von der Goltz | Commander Geb.Jg.Rgt. 144 | 316 | November 2, 1943 |

| Lieutenant General | Paul Klatt | Commander 3rd GebDiv | 686 | December 26, 1944 |

Bearer of the Knight's Cross

The following members of the division were awarded the Knight's Cross (order according to the chronological award):

| Rank | Surname | unit | Award date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant General | Eduard Dietl | Commander 3rd GebDiv | May 9, 1940 |

| Colonel | Alois Windisch | Commander Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | June 20, 1940 |

| major | Hans von Schlebrügge | Commander I./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | June 20, 1940 |

| major | Ludwig Stautner | Commander I./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | June 20, 1940 |

| Captain | Viktor Schönbeck (1910–1983) | Company commander 13./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | June 20, 1940 |

| lieutenant | Hans Rohr | Platoon leader 7./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | June 20, 1940 |

| Captain | Wilhelm Renner | Born Jg.Rgt. 138 | 5th August 1940 |

| Lieutenant colonel | Wolf Hagemann | Commander III./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | 4th September 1940 |

| major | Arthuer Haussels | Commander II./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 139 | 4th September 1940 |

| major | Anton Holzinger | Commander I./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 | January 11, 1941 |

| Colonel | Friedrich Friedmann | Commander Geb.Jg.Rgt. 144 | February 12, 1942 |

| First lieutenant | Walter Giehrl | Company commander 7./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 | July 31, 1942 |

| Colonel | Paul Klatt | Commander Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 | January 4, 1943 |

| First lieutenant | Hans May | Btl-Kommandeur Geb.Jg.Rgt. 138 | January 25, 1943 |

| First lieutenant | Wolfhart Wicke | Head of 5th / Birth year Rgt. 144 | February 8, 1943 |

| First lieutenant | Max Boehrent | assumed | February 8, 1943 |

| Captain | Franz List | Commander II./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 144 | March 3, 1943 |

| sergeant | Kurt Trippensee | Platoon leader 7./Geb.Jg.Rgt. 144 | April 2, 1943, posthumously |