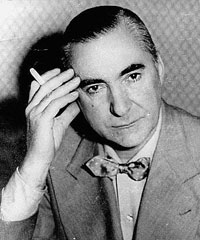

Curzio Malaparte

Curzio Malaparte (born June 9, 1898 in Prato , Tuscany , † July 19, 1957 in Rome ; actually Curt Erich Suckert - the pseudonym Malaparte used from 1925 literally means the bad part and is an allusion to Bonaparte , the good part ) was an Italian writer, journalist and diplomat.

Life

Malaparte was the son of the textile engineer Erwin Suckert from Zittau in Saxony and Edda Perelli from Milan . He attended the Cigognini high school in Prato and in 1911 became a member of the Partito Repubblicano Italiano . In 1912 his first poems appeared in print. In 1913 he became the editor of a satirical magazine. During the First World War he volunteered in the French Foreign Legion in 1914 and fought in the Italian army after Italy entered the war in 1915. In 1918 he was awarded the Italian bronze medal for bravery and the French war cross with palm. As a result of a gas attack, he suffered from lung damage until the end of his life.

After the war he entered the diplomatic service and in 1919 became attaché to the Italian embassy in Warsaw . He initially sympathized with fascism , became a member of the Partito Nazionale Fascista in 1921 and took part in the March on Rome in 1922 . In 1926 he was one of the founding members of the magazine 1900 - Novecento , which had set itself the task of renewing and de-provincialization of Italian culture. 1900 was intended to enable an examination of the international cultural avant-garde and to contribute to the development of future-oriented forms of literature. Fascism was included as a possible future perspective. In 1927, Malaparte left the Novecento editorial team and switched to the Strapaese movement, which pursued the opposite agenda and understood the provincial folk to be the origin and center of Italian culture.

With his book Viva Caporetto! later published under the title La rivolta dei santi maledetti ( The Revolt of the Damned Saints ), it sparked protests among the fascists; in it he described his war experiences. As a result, he was recalled from the diplomatic service.

1928–31 he was editor-in-chief of the large daily La Stampa and the smaller magazine Fiera Letteraria . In 1933 he was arrested on the basis of critical statements, expelled from the party and then sentenced to five years' exile in Lipari . In the following year, however, after influential friends (including Count Galeazzo Ciano , son-in-law of Benito Mussolini ) had stood up for him, he was allowed to leave Lipari again. He subsequently lived under house arrest in Tuscany and Ischia and was able to continue working as a journalist, albeit initially only under a pseudonym .

In 1937 he founded the literary magazine Prospettive . In 1938 he went to Ethiopia, which had been annexed by Italy two years earlier, as a correspondent . During World War II , Malaparte wrote as a war correspondent for the Milanese newspaper Corriere della Sera in North Africa, France, Germany and 1940–45 in the Balkans, Finland and Russia. This is where the Volga rises in Europe , eyewitness reports from the Ukraine front and the Leningrad blockade published in 1943. In 1943 he became a liaison officer for the Americans. In the post-war period, Malaparte turned to communism and maintained a personal friendship with Palmiro Togliatti , but did not want to commit himself ideologically and was at the same time a member of the Partito Comunista Italiano and the Partito Repubblicano Italiano . He was diagnosed with lung cancer while on a trip abroad to China. Shortly before his death, he converted to Catholicism .

plant

During and after the Second World War, Malaparte caused a sensation with his novels Kaputt (1944) and Die Haut (1949), in which he described the brutality and violence of the war in a drastic and realistic manner (negative voices say lurid), at the same time distant. In Kaputt , Malaparte et al. a. an earlier report on the Iași pogrom at the end of June 1941. Thanks to the commitment of Gerhard Heller and Hellmut Ludwig, who translated them into German, Malaparte's works were published in German by Stahlberg Verlag , Karlsruhe. Since the former German diplomat Gustaf Braun von Stumm felt his personal rights had been violated by the portrayal of the protagonists "Ministerialrat R." and his wife "Margherita", presented in Kaputt in 1951 , he tried to stop the distribution of the novel before the Karlsruhe district court. The legal dispute ended in a settlement and a declaration of honor in favor of Braun von Stumms by the publisher. Since the court was unable to impose punishment on foreigners in absentia, the proceedings against Malaparte were temporarily suspended.

In addition to realistic prose reports such as the novels mentioned, he wrote lyrical and essayistic texts and also some plays, including Du coté de chez Proust , Das Kapital (both 1951) and Anche le donne hanno perso la guerra (1954).

Villa Malaparte

Malaparte is also worth mentioning as the builder of Villa Malaparte , a villa on Capo Massullo on Capri famous for its architectural design language , which he had built by the prominent architect Adalberto Libera at the end of the 1930s . He described the house as "una casa come me: dreary, dura, severa" ("a house like me: sad, hard, strict"). The house was bequeathed by Malaparte to the Communist youth of Red China. After a long-standing legal dispute, however, an Italian court ruled that the will was not enforceable. The property is currently privately owned again. It is still one of the most famous and impressive buildings on the island of Capri. The house can be seen in detail in the Godard film The Contempt .

Publications

- The revolt of the damned saints. 1921.

- The technique of the coup . Political essays. 1931

- Blood . Stories. 1937.

- The Volga rises in Europe. Reports. 1943.

- Broken . Novel. Translated by Hellmut Ludwig. Stahlberg, Karlsruhe 1951

- The capital. A play . Karin Kramer Verlag, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-87956-145-1 . (First edition 1947; original title: Das Kapital. Pièce en trois actes )

- The skin. Novel. (= Fischer-Taschenbuch 17411). Translated into German by Hellmut Ludwig. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-596-17411-9 . (Original title: La pelle). German first edition Karlsruhe (Stahlberg Verlag) 1950.

- Damn Italians . 1961. (posthumous)

- Between earthquakes. Forays of a European eccentric. Eichborn, Frankfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-8218-4582-1 , series Die Other Bibliothek 267, (posthumous)

Filmography

Literary template

- 1980: The skin ( La pelle )

Direction, book, music

- 1951: The Forbidden Christ ( Il Christo proibito )

literature

- Astrid Arndt: Tremendous sizes. Malaparte, Celine , Benn . Valuation problems in German, French and Italian literary criticism (= studies on German literature. Volume 177). Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-484-18177-X .

- Manfred Hardt : History of Italian Literature. From the beginning to the present . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-39961-6 , pp. 714 and 736.

- William Hope: Curzio Malaparte. The narrative contract strained . University Press, Hull 2000, ISBN 1-899293-22-1 .

- Torsten Liesegang (Ed.): Curzio Malaparte. A political writer . Publishing house Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8260-4639-1 .

- Sabine Witt: Curzio Malaparte (1898–1957). Autobiographical narration between reality and fiction (= Basics of Italian Studies. Volume 8). Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57894-0 .

Web links

- Curzio Malaparte in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Curzio Malaparte in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Curzio Malaparte in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- “The political juggler. Curzio Malaparte - journalist, writer, dandy ” , SWR2 - radio feature , March 20, 2008, with downloadable manuscript , (40.1 kB; RTF ) and audio file (26:22 min.)

- “The soul could no longer be saved” , Frankfurter Rundschau , July 3, 2006

- "The Man from Prato" , private website

Individual evidence

- ↑ Malaparte's visions. In: Der Spiegel . Issue 5, January 28, 1953, p. 32 online (accessed January 30, 2015)

- ↑ The Spiegel reported. In: Der Spiegel. Issue 1, January 1, 1954, p. 33 online ( Memento from January 30, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed January 30, 2015)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Malaparte, Curzio |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Suckert, Kurt Erich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian writer and journalist of German descent |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 9, 1898 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prato (Tuscany) |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 19, 1957 |

| Place of death | Rome |