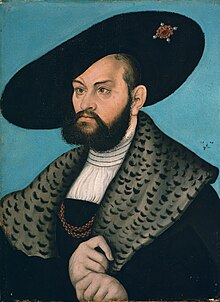

Albrecht (Prussia)

Albrecht von Prussia (born May 17, 1490 in Ansbach ; † March 20, 1568 at Tapiau Castle ) was a Prince of Ansbach from the Franconian line of the Hohenzollern and from 1511 the last Grand Master of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. He converted to the Reformation in 1525 , secularized the Teutonic Order in Prussia in its capacity as a religious community and, as the first Duke of Prussia, transformed the Catholic- dominated secular rule of the Teutonic Order State in Prussia into the hereditary Lutheran Duchy of Prussia , which he held as Duke until his death ruled.

origin

Albrecht was born on May 17th, 1490 in Ansbach. His father was Friedrich V , Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach . His mother Sofia Jagiellonka was a daughter of the Polish king Casimir IV Jagiello and Elisabeth von Habsburg , a daughter of the German king Albrecht II and granddaughter of Emperor Sigismund . His parents determined Albrecht to pursue a spiritual career in accordance with the Dispositio Achillea .

Life

At the age of 21, the Teutonic Order elected him 37th Grand Master in 1511. The order intended to shake off the army succession entered into against the King of Poland in the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466 . The prerequisite was that the newly elected Grand Master refused to take the feudal oath against King Sigismund I. Therefore, Albrecht, the son of a ruling prince of the Holy Roman Empire and nephew of Sigismund, appeared to the chapter of the order to be particularly suitable for the office of Grand Master. Trusting in the assistance of the German master and the land master of Livonia , Albrecht refused the Polish king the oath of feud. However, Sigismund received a warning from the Pope to Albrecht in 1513 and in 1515 Emperor Maximilian recognized the peace of 1466, for which he supported his kingship in Bohemia and Hungary in return.

After Maximilian's successor Charles V had asked Albrecht to take the oath of feud when he ascended the throne in 1519 and it had become clear that Albrecht was not to be expected to support Albrecht either from the Reich or from Livonia, Polish troops fell into the Order of the Order in the course of the equestrian war in the winter of 1519/1520 one to subdue the order. Contrary to expectations, no decision was made. Danish support, a mercenary army from the empire and above all fear of Russia , which was allied with Albrecht, prompted Sigismund to conclude a four-year armistice with Albrecht, whose mercenaries became increasingly rebellious, in April 1521 through the mediation of the Pope and the Emperor .

Over the next two years, Albrecht's search for support in the Reich was unfortunate, while Sigismund came to terms with Moscow. In 1522, Albrecht was won over to the Reformation by Andreas Osiander during the religious wars in Nuremberg . On Luther's advice, he decided in November 1523, confirmed by Sigismund's envoy Achatius von Zehmen , to resign from the office of Grand Master, to convert the Teutonic Order into a secular duchy and there, after Reformation ideas had already come into the country and Bishop Georg von Polentz at Christmas 1523 held the first Protestant sermon in Königsberg Cathedral to officially introduce the Reformation. On April 8, 1525, Albrecht subordinated himself to the Polish King Sigismund on a feudal basis in the Treaty of Krakow and took the oath of homage to Sigismund in Krakow , in which he took Prussia as a duchy inheriting in a straight male line. His brothers Kasimir and Georg were also enfeoffed . At the state parliament, which was held shortly afterwards in Königsberg , all the estates, headed by the Bishop of Samland , Georg von Polenz , declared themselves in favor of recognizing the duchy and accepting the Reformation.

Albrecht put all his energy into carrying out his work. Immediately appeared a new church order , and to repress the attempts of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht again, and the Imperial Court procured against the Duke in Germany in 1531 and imposed on 18 January 1532 outlawry had no other effect than that of the introduction of the evangelical doctrine and was all the more eager to consolidate his rule. That meant the end of the religious order in Prussia.

Albrecht promoted the school system in particular: he set up Latin schools in the cities , founded the grammar school in Königsberg in 1540 and the Albertus University in Königsberg in 1544 , and appointed Andreas Osiander as professor of theology in 1549 . He had German school books ( catechisms etc.) printed at his own expense, and he gave freedom to serfs who wanted to devote themselves to teaching. The text of the first three stanzas of the hymn, What my God wills, always happens from him ( Evangelical Hymnal No. 364). Albrecht also laid the foundation for the royal library , the 20 most magnificent volumes of which he had covered in pure silver for his second wife, Anna Maria von Braunschweig . It was therefore given the name Silver Library .

The last years of his reign were often made bitter by ecclesiastical and political rifts. The dispute between the Königsberg professor Andreas Osiander, who was violently hostile to Melanchthon , with his colleagues, namely Joachim Mörlin , gave rise to serious complications. The duke stood on the side of Osiander, the majority of the clergy, supported by the people, and so did the cities and the aristocracy , who had been expelled from the country , because the former recognized their former privileges, the latter the restriction of the ducal power hoped to achieve the relationship of the former Grand Master to his order. Almost the whole country was hostile to the prince, who was accused of favoring foreigners too much, in fact had allowed himself to be ruled by the Croatian adventurer and polymath Stanislav Pavao Skalić for many years and was also very much in debt. The estates sought help in Poland. Thereupon Poland sent a commission to Königsberg in 1566, which decided against the duke. The Duke's confessor Johann Funck , Osiander's son-in-law, and two allies were sentenced to death as high traitors , Mörlin was recalled and appointed Bishop of Samland. As such, he wrote the symbolic book of Prussia to condemn Osiander's teachings: Repetitio corporis doctrinae Prutenicae . New councils were imposed on the duke by the Polish commission and the estates. Dependent on them, Albrecht spent his last days in deep grief.

Albrecht died of the plague on March 20, 1568 at Tapiau Castle , 16 hours after him his second wife Anna Maria.

Duke Albrecht as an Osian Christian and lay theologian

If Walther Hubatsch emphasizes in his biography that Albrecht was a prince "who was far superior to his peers in theological knowledge and insights", then this judgment, which requires an overview of the princely society of that time, will be well founded. If one follows his life from the point of view of his theological interests, then it is confirmed that the duke showed a sustained interest not only in the religious, especially theological questions of his time - until his death in 1568. His professional knowledge increased over the years Depth and breadth. "A history of Osiandrism after Osiander's death (1552) would not have existed to such an extent without Duke Albrecht." ... "The Duke was the motor and backbone of this theological trend."

The young Albrecht received the minor orders early and received a "cosmopolitan and religious education" in Cologne. It was there that he probably also acquired scholastic ideas from the Dominicans himself - even before his meeting with the Nuremberg reformer Andreas Osiander - which was later reflected in his thinking. He was elected the youngest Grand Master of the Teutonic Order in 1511 and was involved in this office with secular, political and spiritual matters and remained so from 1525 as Duke and sovereign of his Protestant Prussian regional church.

In addition, he met Andreas Osiander in Nuremberg around 1522, whose Reformation sermon impressed him. Luther's writings and ultimately his meeting with the reformer and Melanchthon in Wittenberg in 1523 won him over to the Reformation, which then resulted in the conversion of the religious order in Prussia into a secular duchy. Concerning the Reformation ideas, not least in the form of Osiander, the Duke acquired knowledge from the church father Augustine and other ancient theologians. Of these he was later familiar with a long list of names well into old age. The theology of these church fathers was probably conveyed to him through so-called florilegia , collections of quotations and excerpts from texts that his court theologians prepared for him. He penetrated these theological models of thought so deeply that he could argue with them and also introduce others to these ideas. Ultimately, after Osiander's death in 1552, he was able to represent his theology (including important sources) in detail, so that Osiandrism in the duchy continued to exist until around 1566, until it finally failed with the Repetitio corporis doctrinae , 1567, while Albrecht personally held fast to his views.

If you want to penetrate Albrecht's world of thought, since there is hardly any (modern) printed matter in contrast to the completed Osiander edition, you have to go to the archives of the former state archive in Königsberg , today in Berlin (Dahlem), especially the Ducal letter archive. These sources include song texts from Albrecht's pen, prayers, confessions, essays and many detailed discussions in his correspondence. - In more recent research, Henning P. Jürgens points out that Timothy J. Wengert's book is based only on printed sources and evaluates Osiander's teaching almost exclusively with regard to the formation of Protestant-Orthodox denominations, essentially according to Melanchthon's position. The extensive contemporary pamphlet literature of the opponents of Osiander is also brought into the field in this way. The earlier works of Martin Stupperich and Jörg Rainer Fligge should also be used, which were based on the archival sources. The role of Duke Albrecht is underestimated. It is not clear why there were so many supporters of Osiander's concerns in Prussia and Nuremberg.

The discussion at that time is hardly understandable for today. But if one wants to roughly understand the historical phenomenon of the " Osiandrian dispute ", one must - here from Duke Albrecht's point of view - bring to mind some central theological key points. Since Augustine God has been regarded as the highest being, being itself. God is the highest good and, according to the Osiandrists, also essentially the highest justice. The mediator Christ brings this essential righteousness and has "taken for himself" his humanity. Although of divine origin (within the framework of the doctrine of the Trinity ) it is now about the Savior and at the same time the historical man Jesus, who was crucified at Golgotha. The death on the cross was done for sinful people for their redemption. Through his act, the vicarious punishment on the cross, his blood, which was shed “for all of us”, Jesus Christ made it possible for sinners to speak righteously. This is called the “forensic justification” (doctrine), in which one is figuratively before God's judgment. Melanchthon's followers then spoke of “imputation”, the crediting of Christ's suffering in order to be justified. For Luther, the dialectical formulation “just and sinner at the same time” played a role, because the justified sinner (the believer) does not walk through life like a saint for the rest of his life. Luther, based on Paul, wanted to make it clear that man cannot work out eternal life (being righteous) through good works (alone), but that it is graciously given to believers (through grace) through the entry of Christ. The Osiandrists, including the Duke, viewed this salvation event from the perspective of the “essential righteousness” that resides in God and that “dwells” the believer when they “grasp” Christ in faith. Ultimately, an intended mystical substance unity between the believer and the deity plays a role and takes precedence over imputation.

If Johannes Brenz (1499–1570), the respected Württemberg reformer who was so often mediating, prevented Osiander from being convicted at the Worms Religious Discussion in 1557, one has to ask: "Why?" What spoke to him in Osiander's theology and was it an indispensable part of the Protestant conception of doctrine for him? The bridge forms - and the Duke also keeps pointing out - the doctrine of the sacraments. As is well known, Luther stubbornly fought for his conception that Christ was present in the Lord's Supper and that the believer received the blood and body of Christ into himself. This oneness with Christ belongs to the evangelical conception of the Lord's Supper (not a mere remembrance meal, no transubstantiation as with the Catholic sacrifice of the Mass), and the Osiandrists found their belief that Christ indwells the believer confirmed here. Similar things take place in baptism, and the connection to the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ was always present to them in this context. Perhaps it was the understanding of a certain piety that one believed that one felt that something was changing in the believer. The brittle forensic and legal affirmation of a merciful judgment (before God's court) was not enough. The Osiandrists aimed for a renewed, joyful awareness of Christianity and spoke of a tangible unity with their Savior. Church ordinances, revocations, and teaching confirmations could not close this gap. In reality, Orthodoxy, with its righteousness, had moved a bit away from Luther, not in the letter, but in the spirit, even if the tradition-saturated speculation of substance of the Osiandrists was more suitable for academic discussions, but not as a foundation for a regional church.

Works (selection)

- Trust God alone. Prayers Duke Albrechts of Prussia. Edited by Erich Roth. Würzburg: Holzner, 1956.

- "Whatever my God wants, happen always." Hymn No. 364 in the Evangelical Hymnal , verses 1–3 by Duke Albrecht, 1547 and around 1554; Verse 4: Nuremberg around 1555.

- 16 contemporary ecclesiastical prints by Duke Albrecht (hereinafter with simplified short titles. Evidenced with line breaks, abbreviations, in the spelling of the time, including print versions from: Jörg Rainer Fligge: Herzog Albrecht und der Osiandrismus 1522–1568. Diss. Phi. Bonn 1972. p. 858-864).

- Christian responsibility of ... Herr Albrechte ... outings in our Stat Koenigsberg in Prussia ... (Printed: J. Gutknecht, Nuremberg, 1526. No. 1.a).

- Illustris. Principis… Alberti… responsio contra insimulationem… Theoderici de Clee… (Printed: H. Weinreich, Königsberg, 1526. No. 2).

- Vermanung to the Christian community ... (Printed: o. O. and o. J., single-sheet print, folio format. No. 3).

- Confession: a Christian person… (Printed: Königsberg in Preussen, 1551. No. 4.a).

- BY God's grace Vnser Albrechte… Write out… (Printed: Hans Lufft, Königsberg, 1553. No. 5a).

- Farewell to the ... Mr. Albrechte of the parents ... according to which all ... should keep. (Printed: Johann Daubmann, Königsberg, 1554. No. 6a).

- The most transparent… Mr. Albrechte of the parents… mandate… (Printed: Johann Daubmann, Königsberg, 1554. No. 7).

- The 71st psalm put in a prayer by a high person in charge of the office… (reprinted by Friedrich Spitta in: Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 6. 1908/09. Pp. 140–146. No. 8).

- Preface to: Enchiridion. The little catechism of Doctor Martini Luther… (Printed: Johann Daubmann, Königsberg, 1561. No. 9).

- Vermanung At penance. Of ... Mr. Albrechte of the parents ... (in the presence of the prince and his wife, councilors etc.) ... publicly in the Thumkirchen there on December 23rd. Anno 63. Read by M. Johann Funck… (Printed: Johann Daubmann, Königsberg, 1564. No. 10).

- Church prayer in the Duchy of Prussia (1563) (single-sheet print. Reprinted by: Walther Hubatsch, Geschichte der Evangelische Kirche Ostpreussens. Vol. 3, p. 32f. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968. - No. 11).

- Illustrissimi Principis ac domini, domini Alberti… Ducis Prussiae etc.… Responsio & Confessio . (Printed: only with the year: 1564. No. 12).

- From God's Genaden Albrecht des Eltern… Briefze and unequivocal answer and confession… (Printed: Johann Daubmann, Königsberg, 1564. No. 13).

- (Scalich.Mandat: regarding Stanislav Pavao Skalić) From God's approval We Albrecht the Parents… Given in our castle Königsperg on Sunday June 2nd Anno 65. (single-sheet print in Folio. No. 14).

- Princely transparency Marggraff Albrechte deß first drawn in Prussia etc.… Public written notice due to clouded university through the whole of Herzogthumb in 1558. (Renewed published: December 11, 1618. No. 15).

- Fürsten Spiegel That is: Writings and letters of the ... Mr. Albrecht ... first hired in Prussia etc. ... (Ed. By Holger Rosenkrantz. Printed: Hans Hanssen, Aarhus, 1636. No. 16).

The Croatian humanist, priest, polymath and author of the first work, in the title of which the word “ encyclopedia ” occurs in today's meaning, Pavao Skalić , was Albrecht's advisor.

Marriages and offspring

Duke Albrecht married Dorothea , daughter of Frederick I (Denmark and Norway), on July 1, 1526 in Königsberg . There were six children from this marriage:

- Anna Sophie (June 11, 1527 - February 6, 1591)

- ⚭ 1555 Duke Johann Albrecht I of Mecklenburg (1525–1576)

- Katharina (* / † February 24, 1528)

- Friedrich Albrecht (December 5, 1529 - January 1, 1530)

- Lucia Dorothea (April 8, 1531 - February 1, 1532)

- Lucia (February 1537 - May 1539)

- Albrecht (* / † March 1539)

In his second marriage he married Anna Maria von Braunschweig , daughter of Duke Erich I (Braunschweig-Calenberg-Göttingen) in Königsberg on February 16, 1550 . There were two children from this marriage:

- Elisabeth (20 May 1551 - 19 February 1596)

- Albrecht Friedrich (April 29, 1553 - August 27, 1618), 2nd Duke in Prussia

- ⚭ 1573 Princess Marie Eleonore von Jülich-Kleve-Berg (1550–1608)

Commemoration

A portrait relief of Duke Albrecht had been at the Collegium Albertinum (Königsberg) since 1553 .

In the Evangelical Name Calendar , it is remembered on March 20th

The Herzog-Albrecht-Gedächtniskirche , built in 1913 in Königsberg, was demolished in 1972.

Ansbach honors the founder of the first Evangelical Lutheran regional church with a monument by the sculptor Friedrich Schelle.

The Kant University of Kaliningrad (Königsberg), supported by the Russian administration, honored Duke Albrecht as the founder of the university (1544) with an artistically crafted monument. The statue of the Duke is on a lightly tinted base, roughly life-size, black, in the national costume of that time. Two inscriptions, in gold, in Russian and German, say: "Duke Albrecht // Founder // of the Königsberg // University". The monument is not far from the grave of Immanuel Kant (d. 1804) at the cathedral.

See also

literature

- Stephan Herbert Dolezel: The Prussian-Polish feudal relationship under Duke Albrecht of Prussia (1525–1568) (= studies on the history of Prussia. Ed. By Walther Hubatsch . Volume 14). Grote, Cologne and Berlin 1967.

- Erich Joachim: The policy of the last Grand Master in Prussia Albrecht von Brandenburg . 3 parts. Hirzel, Leipzig 1892–1895 ( digitized version )

- European letters in the age of the Reformation. 200 letters to Margrave Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach, Duke in Preusse , ed. by Walther Hubatsch, Kitzingen / Main 1949

- Kurt Forstreuter : On the war studies of Duke Albrecht von Prussia , Altpreußische Forschungen 19 (1942), pp. 234–249; ND in: Ders .: Contributions to Prussian history in the 15th and 16th centuries (= studies on the history of Prussia 7), Heidelberg 1960, pp. 56–72

- Walther Hubatsch : Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach. Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and Duke in Prussia 1490–1568 . Grote, Cologne, Berlin 1965 [new edition]

- Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522–1568. Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. (Rotaprintdruck der Universität) 1078 p., 57 ill., Index.

- Oliver Volckart: The coinage policy in the monastic country and the Duchy of Prussia from 1370 to 1550 , Wiesbaden 1996 ( digitized version )

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Albrecht of Prussia. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 93-94.

- K. Lohmeyer: Albrecht . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1875, pp. 293-310.

- Walther Hubatsch : Albrecht the Elder. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , pp. 171-173 ( digitized version ).

- Almut Bues and Igor Kąkolewski (eds.): The wills of Duke Albrecht of Prussia from the sixties of the 16th century (= German Historical Institute Warsaw. Sources and studies; Vol. 9). Wiesbaden 1999

- Jürgen Manthey : The birth of secular rule (Duke Albrecht) , in ders .: Königsberg. History of a world citizenship republic . Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-423-34318-3 , pp. 37-47.

- The order of war of the Margrave of Brandenburg Ansbach and Duke of Prussia Albrecht the Elder, Königsberg 1555 , 2 volumes. [Facsimile and commentary] on behalf of the MGFA and in cooperation with the DHI Warsaw ed. by Hans-Jürgen Bömelburg, Bernhard Chiari and Michael Thomae, Braunschweig 2006

- Almut Bues (Hrsg.): The Apologies of Duke Albrechts (= German Historical Institute Warsaw. Sources and Studies; Vol. 20). Wiesbaden 2009

- Stefan Hartmann: Duke Albrecht's statements on the military in previously little known sources - war book and correspondence . In: Contributions to the military history of Prussia from the time of the order to the age of the world wars. Dedicated to Sven Ekdahl on the occasion of his 75th birthday on June 4, 2010 , ed. von Bernhart Jähnig (= Publications of the Commission for East and West Prussian State Research 25), Marburg 2010, pp. 191–232

- Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach and the culture of his time. Exhibition catalog of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn . Rheinland Verlag, Düsseldorf 1968

Web links

- Literature by and about Albrecht in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Albrecht in the German Digital Library

- KP Faber: Letters from Luther to Duke Albrecht (1811)

Individual evidence

- ↑ On this and the following Dolezel (literature), pp. 16-19

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach. German Order Master and Duke in Prussia 1490-1568. Cologne, Berlin: Grote; Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1960. pp. 117, 141f. - Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522–1568 . Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 16-22.

- ^ Karl Alfred von Hase: Georg von Polentz . In: Allgemeine deutsche Biographie (ADB) . tape 26 . Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1888, p. 382-385 .

- ^ General Archive for the History of the Prussian State . Volume 5, Issue 1, Berlin Posen Bromberg 1831, pp. 67-73

- ↑ State Archives Ludwigsburg JL 425 Vol. 38 Qu. 126

- ^ Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522–1568 . Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972, pp. 183-316 (deals with the attempts at unification after Osiander's death), pp. 449-525 (describes the decline of Osiandrism up to the victory of Orthodoxy).

- ^ Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522–1568. Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 589, 587.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach. Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and Duke in Prussia 1490-156 8. Cologne, Berlin: Grote; Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1960. pp. 21f., 28f., 30ff. - Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522–1568 . Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 266, 528f., 554, 556, 576, 582f., 585.

- ^ Walther Hubatsch: Albrecht von Brandenburg-Ansbach. Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and Duke in Prussia 1490-1568. Cologne, Berlin: Grote; Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1960. S. 117ff.

- ^ Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522–1568 . Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 528f., 562, 575f., 581ff., 586.

- ^ Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522-1568 . Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 526ff., 537-552.

- ↑ Timothy J. Wengert: Defending Faith. Lutheran responses to Andreas Osianders doctrine of justification, 1551-1559 . (Late Middle Ages, Humanism, Reformation. 65) Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012. ISBN 978-3-16-151798-3 ; 1865-2840. There p. 1f., 460 (index), on Fligge, Herzog Albrecht von Preussen and the Osiandrismus , Diss. Phil., Bonn, 1972: “It has remained, until now (2012), the only full-length study of the Andreas Osiander's proposals reactions for understanding the Lutheran doctrine of justification by faith. ”(p. 1) - On Wengert: Review by Henning P. Jürgens in: The Journal of ecclesiastical history, Cambridge , Vol. 1950 (2), 2014, Pp. 427-429. - Martin Stupperich: Osiander in Prussia. (Works on church history. 44) Berlin: de Gruyter, 1973. ISBN 3-11-004221-5 . - See also: Irene Dingel in: Lutheran ecclesiastical culture , 1550–1675. Ed. by Robert Kolb. (Brill's companions to the Christian Tradition, Vol. 11) Leiden: Brill, 2008. pp. 54f. ISBN 978.90-04-16641-7.

- ↑ Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht and Osiandrism 1522-1568. Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 526-589. - Cf. Fligge: On the interpretation of the Ottoman theology of Duke Albrechts of Prussia. In: Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte 64. 1973. pp. 245–280.

- ^ Jörg Rainer Fligge: Duke Albrecht of Prussia and Osiandrism 1522-1568. Diss. Phil. Bonn 1972. pp. 865–867 (printed statements by Brenz); Pp. 371-448 (on Worms, 1557).

- ↑ a b European Family Tables Volume I.1 1998 ISBN 3-465-02743-4 ; Plate 139

- ^ Robert Albinus: Königsberg Lexicon . Würzburg 2002, p. 37

- ↑ Albrecht of Prussia in the ecumenical dictionary of saints

- ↑ Ansbach: A memorial for the founder of the first regional church. In: ideaSpektrum 22/2016, June 1, 2016, p. 24

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| --- |

Duke in Prussia 1525–1568 |

Albrecht Friedrich |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Albrecht |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Albrecht of Hohenzollern; Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, first Duke of Prussia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 17, 1490 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ansbach |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 20, 1568 |

| Place of death | Tapiau Castle |