trinity

Trinity , Trinity or Trinity ( Latin trinitas ; ancient Greek τριάς triad 'three number', 'trinity') in Christian theology denotes the essential unity of God in three persons or hypostases , not three substances . These are called “Father” ( God the Father , God the Father or God the Father ), “Son” ( Jesus Christ , Son of God or God the Son ) and “ Holy Spirit ” ( Spirit of God ). This expresses their distinction and their indissoluble unity at the same time.

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity has been developed since Tertullian by various theologians, especially Basil the Great , and synods between 325 ( First Council of Nicaea ) and 675 (Synod of Toledo). The two main opposing directions were the one- hypostasis view and the three-hypostasis view. At the beginning of the Arian dispute in 318, the presbyter Arius from Alexandria represented the view of the three hypostases God, Logos and Holy Spirit, Logos and Holy Spirit in subordination , the Logos son was to him as created and with a beginning and therefore not as true God. The bishops Alexander and later Athanasius, who also came from Alexandria, represented the view of a hypostasis with God, Logos and Holy Spirit (with equality of father and son), so that the Logos son or Christ counted as true God at the same time could redeem humanity through his work. Later it was also about the position of the Holy Spirit. After the three-hypostasis position temporarily dominated in Christianity in the eastern part of the Roman Empire during the 4th century , while the one-hypostasis position in the western part, a new compromise formula developed up to the first Council of Constantinople or Council of Chalcedon in the creed with three equal hypostases God-Father, God-Son Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit from the common divine essence. Today, anti-Trinitarians and Unitarians are in the minority.

In the church year , Trinity , the first Sunday after Pentecost , is dedicated to the commemoration of the Trinity of God.

The idea of a divine trinity ( triad ) also exists in other religions, such as the ancient Egyptian with Osiris , Isis and Horus . Also, the Hindu knows a trinity: the trimurti consisting of the gods Brahma , Vishnu and Shiva . The extent to which pre-Christian ancient concepts have analogies to the doctrine of the Trinity or even influenced their development is controversial. In Judaism and Islam, the concept of the Trinity is rejected.

Biblical motifs

According to Christian interpretation, the Old and New Testaments contain references to a doctrine of the Trinity, but without developing such a doctrine. In addition to formulas that were directly related to the Trinity, statements about the divinity of the Son and Spirit are also significant for the history of reception.

Divine Trinity

Old Testament motifs

The New Testament talk of the Holy Spirit has precursors in formulations of the Old Testament, for example Gen 2.7 EU ; Isa 32.15-20 EU ; Ez 11.19 EU or 36.26 f. EU and contemporary theology, in which there are also certain parallels for ideas that are associated with Jesus Christ in the New Testament. Any further references are later reinterpretations. For example, early Christian theologians generally refer to passages where the angel, word (davar), spirit (ruah) or wisdom (hokhmah) or presence (shekhinah) of God are mentioned, as well as passages where God speaks of himself in the plural speaks ( Gen 1.26 EU , Gen 11.7 EU ) and especially the threefold “Holy!” of the Seraphim in Isa 6,3 EU , which was included in the liturgy in Trisagion . Again and again the appearance of three men in Gen 18: 1-3 EU was related to the Trinity. In the Jewish religion, however, the idea of the Trinity is rejected.

New Testament motifs

The specification of an “immanent will” of God, which was already manifest in the Old Testament, as well as a speech in “non-interchangeable” names of spirit, son and father has been diagnosed.

In any case, Paul shaped the earliest formulations relevant to the history of action . It uses in 2 Cor 13,13 EU probably a blessing greeting the early Christian liturgy: "The grace of Jesus Christ, the Lord, the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you!" In 1 Corinthians 12.3 to 6 EU are Gifts of grace “in a targeted increase” traced back to Spirit, Lord and God. Also Eph 1.3 to 14 EU allocates Father, Son and Spirit side by side and each other out.

The baptismal formula in Mt 28:19 EU is particularly influential in terms of history, even if it is not the “prototype of Christian baptism” . “In the name” (εἰς τὸ ὄνομα, literally “in the name”) denotes a transfer of ownership. The story of the baptism of Christ in the Jordan by John the Baptist has been seen as a "counterpart" , because there, through the floating down of the spirit and the heavenly voice of the father, father, son and spirit are also united. Presumably this baptismal formula is the extension of a baptism “in the name of Christ”. The Didache (the early “catechism with instructions on liturgical practices”), which was created after AD 100 , already knows such an extended baptismal formula: “Baptize in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit”.

Divinity of the Father

The term "God" in the New Testament mostly refers to the Father . God and the Son of God appear to be different from one another when it says, for example: "God sent his Son" ( Jn 3:17 EU ). Or when Jesus “stands at the right hand of God” ( Acts 7.56 EU ). God, that is (e.g. in 1 Petr 1,3 EU ) the "Father of our Lord Jesus Christ". This idea also applies to the future; in the end “the Son too will submit” and be “God all in all” or “in all” ( 1 Cor 15:28 EU ).

Divinity of Jesus Christ

Even the oldest texts of the New Testament show a close connection between God and Jesus : He works with divine authority - so much that God himself accomplishes his creation, judgment, redemption and revelation in Jesus and through him. Among the Christological particularly meaningful texts has about the hymn in Colossians 1.15 EU et seq., The u. a., as Joh 1 EU states , a pre-existence and a creation of the cosmos in Christ. The relationship between Christ as Son of God and God the Father is important to several New Testament authors. A special familiarity is emphasized in the Abba address and the “recognition” of the father by the son; Above all, the Gospel of John ( Joh 17.21–23 EU ) speaks of a relation of unity and mutual immanence between father and son in love.

Joh 20,28 EU is often interpreted to the effect that the disciple Thomas directly referred to Jesus as "God". Thomas says there: "My Lord and my God!" Likewise, the designation “God” is applied to Jesus in some New Testament letters, most clearly 1 Jn 5:20 EU in the phrase “true God”. But there is also an indirect equation of God and Jesus, in that statements such as “I am the Alpha and the Omega” appear both in the mouth of God and in the mouth of Jesus ( Rev 1,8 EU , Rev 22,13 EU ).

Divinity of the Holy Spirit

According to Matthew and Luke, the spirit is already active at the conception of Jesus. The earthly Jesus is then, according to the evangelists, the carrier (“full”) of the Holy Spirit , especially according to Paul the risen Christ, then its mediator. In the Gospel of John the Spirit reveals the unity between Father and Son, even more, Jesus even confesses: “God is Spirit” ( Jn 4,24 EU ), with which the presence and work of God as Spirit becomes believable ( Jn 15,26 EU ; Acts 2,4 EU ).

Development of the theology of the Trinity

Early Trinitarian Formulas

The biblical discourse of the Father, Son and Spirit can only be seen as setting the course for later receptions when working out a doctrine of the Trinity. The ritual practice and prayer practice of the early Christians are particularly influential.

The earliest formulas, clearly structured in three ways, are found as baptismal formulas and in baptismal confessions, which prepare and then carry out the transfer of ownership to the Father, Son and Spirit with three questions and answers.

Trinitarian formulas can also be found in the celebration of the Eucharist : the Father is thanked by the Son, and then asked to send the Spirit down. The final doxology glorifies the Father through the Son and with the Spirit (or: with the Son through the Spirit).

The regula fidei in Irenaeus , which u. a. was used in baptismal catechesis is structured in a trinitarian way.

Theological development in the 2nd and 3rd centuries

Christian theology was not clearly defined in the first few centuries. Soon there were numerous disputes with the variants of Christology and Trinity, such as adoptianism (the person Jesus was adopted by God via the Holy Spirit at baptism) or docetism (Jesus was purely divine and only appeared as a person). Various attempts to differentiate it from Gnosis and Manichaeism with its effects on Christianity included some - such as modalist monarchism (the father and son are different forms of being of the one God in the 'economic history of salvation', so that, to put it bluntly, God himself died on the cross) - who were later condemned as heresy .

Justin

Justin Martyr uses numerous Trinitarian formulas.

Irenaeus

Irenaeus of Lyon developed a logos theology based on the prologue of the Gospel of John (1,1-18 ELB ), among other things. Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is equated with the pre-existing Logos as an essential actor in creation and God's revelation. Irenäus is also working out an independent pneumatology . The Holy Spirit is God's wisdom. Spirit and Son do not emerge through an emanation , which would place them on a different ontological level from the Father, but through “spiritual emanation”.

Tatian

Tatian tries an independent special path, whereby the spirit also appears as a servant of Christ, the Logos, and is subordinate to a God who is unchangeable beyond the world.

Athenagoras

The Greek word trias for God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, which is the common word for the Christian trinity in the Eastern Churches to this day, was first mentioned in the second half of the 2nd century by the apologist Athenagoras of Athens :

“They [Christians] know God and his Logos , what is the unity of the Son with the Father, what is the communion of the Son with the Father, what is the Spirit, what is the unity of this triad, the Spirit, the Son , and the Father, is, and what their distinction is in unity. "

Tertullian

In the Western Church, a few decades after Athenagoras spoke of “trias”, the corresponding Latin word trinitas was probably introduced by Tertullian , at least it is first documented with him. It is a specially created new formation from trinus - threefold - to the abstraction Trinitas - trinity. A lawyer by training, he explained the essence of God in the language of Roman law. He introduces the term personae (plural of persona - party in the legal sense) for Father, Son and Holy Spirit. For the entirety of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit he used the term substantia , which denotes the legal status in the community. According to his presentation, God is one in the substantia , but in the monarchia - the rule of the one God - three personae are at work , the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. According to another version, Tertullian borrowed the metaphor "persona" from the theater of Carthage , where the actors put masks (personae) in front of their faces, depending on the role they were assigned.

Theological development in the 4th to 7th centuries

Doctrines of the Trinity - Council of Nicaea (325)

The contrasts in the ideas of the Trinity in the Roman Church from the late 2nd century onwards can be summarized under the currents of monarchianism , subordinatianism and tritheism . Under the influential but blanket battle term Arianism , a variety of subordinatianism appeared in Arius , which postulates the three hypostases God, Logos-Son and Holy Spirit, but subordinates Logos and Holy Spirit to God, to the Logos-Son as created and with the beginning but the denies true deity - Jesus comes in a middle position between divine and human. This teaching was rejected as heresy by the first Council of Nicaea (325). The hoped-for agreement did not materialize. After the Council of Nicea, there followed decades of theologically and politically motivated dispute between supporters and opponents of the Nicaea Confession. In the years after Nicaea, the 'anti-Nicene' current won many supporters, especially among the higher clergy and the Hellenistic educated people in the eastern part of the Roman Empire at court and in the imperial family, so that in 360 the majority of the bishops voluntarily or forcibly joined the new ' Homoic ' confession compromise formula (see under Arian dispute ). Various 'anti-Nicene' synods met, which formulated between 340 and 360 different 'non-Nicene', Trinitarian creeds.

Pneumatology - Nicäno-Konstantinopolitanum (381)

In addition to the question of the Trinity, which had been in the foreground at the Council of Nicaea, the question of the position of the Holy Spirit was added in the middle of the fourth century . Is the Spirit of God a person of the divine Trinity, an impersonal power of God, another name for Jesus Christ, or a creature?

The Macedonians (after one of their leaders, the Patriarch Macedonios I of Constantinople) or Pneumatomachen (spirit fighters) took the view that God-Son was begotten of God, thus also being in harmony with God, while the Holy Spirit was created.

From 360 the question was taken up by 'Old Nicene' and 'New Nicene'. Athanasius wrote his Four Letters to Serapion . The Tomus ad Antiochenos , written by Athanasius after the regional synod in Alexandria in 362, expressly rejected the creatureliness of the Holy Spirit, as well as the essential separation of the Holy Spirit from Christ, and emphasized its membership of the 'holy trinity'. Shortly afterwards, Gregory of Nyssa gave a sermon on the Holy Spirit , and a few years later his brother Basilius gave a treatise on the Holy Spirit ; His friend Gregory of Nazianzen gave the fifth theological discourse on the Holy Spirit as God in 380. Almost at the same time Didymus the Blind was writing a treatise on the Holy Spirit. The Greek theology of the fourth century uses the Greek word hypostasis (reality, essence, nature) instead of person , which is also often preferred in theology today, since the modern term person is often incorrectly equated with the ancient term persona .

Hilary of Poitiers wrote in Latin on the Trinity and Ambrose of Milan published his treatise De Spiritu Sancto in 381 .

In 381 the first council of Constantinople was convened to settle the hypostasis dispute. There, the Nicano-Constantinopolitanum , which is related to the Nicene Creed, was decided, which in particular expanded the part relating to the Holy Spirit and thus emphasized the Trinity of equal rank more than all previous creeds.

|

The Nicano-Constantinopolitanum formulated the Trinitarian doctrine, which is recognized to this day by both the Western and all Orthodox churches and was adopted in all Christological disputes over the next centuries.

Council of Chalcedony

In the Council of Chalcedony the Christological questions connected with the doctrine of the Trinity were specified.

Augustine

While both the Eastern and Western traditions of the Church have seen the Trinity as an integral part of their teaching since the Council of Constantinople, there are nuances: In the Eastern tradition, based on the theology of Athanasius and the Three Cappadocians , there is a little more value placed on the three hypostases, the Western tradition emphasizes, based on Augustine von Hippo's interpretation of the Trinity a few decades later in three volumes, rather the unity.

Augustine of Hippo argues that it is only through the Trinity that love can be an eternal trait of God. Love always needs a counterpart: a non-trinitarian God could only love after he has created a counterpart that he can love. The triune God, however, has the opposite of love in himself from eternity, as Jesus describes it in John 17:24 ESV .

Filioque dispute

Differing views on the relationship between father, son and spirit ultimately led to the Filioque dispute, which was one of the causes of the Oriental Schism and has not yet been resolved.

Athanasian Creed

In the 6th century the Athanasian Creed, named after Athanasius of Alexandria , but not written by him, arose in the west . The theology of this creed is based heavily on the theology of the western church fathers Ambrosius († 397) and Augustine († 430) and was further developed by Bonaventure von Bagnoregio († 1274) and Nikolaus Cusanus († 1464).

|

Today, most church historians see the Nicano-Constantinopolitanum of 381 as the first and essential binding commitment to the Trinity. The Athanasian Creed, about two hundred years younger and only widespread in the West, never had the theological or liturgical status of the Nicene Constantinople in the Western Church either.

Synod of Toledo (675)

The Catholic Church formulated the doctrine of the Trinity in the 11th Synod of Toledo in 675 as a dogma, confirmed it in the 4th Lateran Council in 1215 and never questioned it afterwards.

Reception history

Exegetical accents of the church fathers

To Christology

Athanasius thinks that the Redeemer Jesus Christ himself must be God, since according to Col 1,19-20 ELB God will reconcile the world with himself .

Athanasius, Gregor von Nazianz and Ambrosius von Milano refer in the 4th century to passages in which Jesus is the only one equated with the Creator in their view, for example Joh 1,1-18 ELB or Phil 2,5-7 ELB and to that Word kyrios (Lord) used in the Greek Septuagint for the Hebrew YHWH (as well as for Adonai , "Lord"), and in the New Testament for both God and Jesus, with kyrios (Jesus) being common in the New Testament stands in the same context as kyrios (YHWH) in the Old Testament (cf. Isa 45.23-24 ELB and Phil 2.10 ELB , Joel 3.5 ELB and Rom 10.13 ELB , Isa 8.13 ELB and 1 Petr 3 , 15 ELB ).

Further biblical passages are: "Before Abraham became, I am." ( Jn 8:58 ELB ) with a reference to the "I am" from 2 Mos 3:14 ELB understood by the audience , and "I and the Father are one" ( Joh 10,30 ELB ), which was understood by the listeners in Joh 10,33 ELB to mean that Jesus made himself God, whereupon they tried to stone him for blasphemy. Thomas calls him "My Lord and my God" in John 20.28 ELB , and in 1 John 5.20 ELB he is called the "true God". Heb 13: 8 ELB ascribes the divine attribute immutability to Jesus: "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today and forever"; in Hebrews 1: 8-10 it says of the Son: "Your throne, O God, endures forever and ever." (Son is called God).

Mt 27.46 ELB is often used as a counter-evidence : “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me”, a literal quotation from the beginning of Ps 22 ELB . Augustine sees the submission of Jesus to the Father as voluntary submission ( Phil 2: 6–8 ELB ), not as a qualitative difference. As a result, he can understand orders that Jesus receives from the Father and carries out as an indication of a different function, not a different rank.

Like many church fathers, Arius interpreted wisdom as an Old Testament expression of Jesus Christ. As a biblical argument against the equality of Christ with God, he mainly referred to the statement of " wisdom " in the book of Proverbs , which says of itself that it was created by God "before the works of primeval times" ( Prov 8:22 ELB ) .

To pneumatology

Basil of Caesarea , Gregory of Nazianzen and Athanasius cite passages in the Bible where the spirit acts as a person and relates to other persons. You can see the z. B. in Joh 16,13-14 ELB , where a masculine pronoun refers to the neutral Greek word πνεῦμα pneuma (spirit). In Rom 8,26 ELB the spirit intervenes for us, in Acts 8,39 ELB he works miracles, in Joh 16,8 ELB he exposes sin, righteousness and judgment. He can be lied to ( Acts 5.3 ELB ), be grieved ( Eph 4.30 ELB ), be blasphemed Mt 12.31 ELB . The apostles use him in Acts 15.28 ELB together with themselves as the subject of the sentence ("The Holy Spirit and we have decided ..."). Basil gives examples of typologies and personifications of abstractions in the Bible, but clearly distinguishes them from the description of the Holy Spirit in the New Testament.

middle Ages

After the development of the dogma itself was completed, it was speculatively thought out and systematically classified in scholasticism .

Thomas Aquinas saw in the second and third person of God the eternal self-knowledge and self-affirmation of the first person, ie God the Father. Because with God knowledge or will and (his) being coincide with his being, his perfect self-knowledge and self-love is of his nature, thus divine.

Johannes Duns Scotus pointed out that only the existence of God can be recognized through reason, as a clear ( univokin ) core of concepts that cannot say anything about his essence. Faithful truths like the Trinity presuppose revelation and belong in the realm of theology. They can only be understood in retrospect through analogies.

Meister Eckhart developed a consequent negative theology . The knowledge of God becomes a momentary event, a mere “sparkle” in which the knower and the known merge again and again into one in the Holy Spirit. The Trinity as a continuous birth of God is a dynamic event of recognition or giving birth and passing away on the border of the world. Eckhart's doctrine of redemption focuses on the incarnation of God , which is a work of the Trinity. The human nature of Christ is none other than that of any other person: "We all have human nature in common with Christ, in the same way and in the same sense (univoce)". Because of the hypostatic union with God, the individual as a participant in the general human nature can be one like Christ. "Man can become God because God became man and thereby deified human nature."

Baroque

In the baroque interpretation of the Trinity there are references to the Pythagorean-Platonic doctrine of ideas, according to which the musical triad, which arises from a harmonic and arithmetic division of the fifth, is a symbolic representation of the Trinity. Although the triad consists of three sounds, it unites into one sound.

present

Social doctrine of the Trinity

In the theology of the 20th century, such trinity theological approaches were particularly important, which start from three divine persons thought to be of the same origin and which emphasize the relationship, the togetherness, for- and in one another of the three that constitute the unity of God. They refer to early church models such as Tertullian's doctrine of the Trinity , the Eastern Church idea of perichoresis and the dictum of Athanasius that the father is only a father because he has a son with whom he opposes the subordination of the son.

Social doctrines of the Trinity are represented by Protestant theologians such as Jürgen Moltmann and Wolfhart Pannenberg , but also by Roman Catholic theologians such as Gisbert Greshake and the liberation theologian Leonardo Boff . Central to these approaches is that they understand the inner-trinitarian community as the Godhead originally and as a model for society and the church. Leonardo Boff in particular understands the triune communion in God as a criticism and inspiration of human society and justifies the liberation-theological option for the poor from a trinity- theological perspective.

Catholic theology

Joseph Ratzinger does not see the motivation for the emergence of the doctrine of the Trinity in speculation about God - that is, in an attempt by philosophical thought to determine the nature of the origin of all being - but rather it resulted from the effort to process historical experience . The interpretation of biblical texts is therefore central. The tradition of interpretation established by the Church Fathers is recognized by all three great Christian traditions. The Fathers of the Church were aware of the historical difference between the biblical language and an interpretation based on a philosophical pre-understanding that can be measured against it and is widely recognized today. The New Catholic Encyclopedia wrote in 1967: “Exegetes and Bible theologians, including an increasing number of Catholics, recognize that one should not speak of a doctrine of the Trinity in the New Testament without significant restrictions.” The second edition of 2003 repeats from Old Testament passages interpreted by the Church Fathers as premonitions could not be understood as explicit revelations of the Trinity. However, 1 Cor 12.4–6 ELB , 2 Cor 13.13 ELB and Mt 28.19 ELB would testify to the faith of the apostolic church “in a doctrine of three persons in one God”, even without using the terminology introduced later.

- Karl Rahner

Karl Rahner understood God to be self-communicating. He refers (indirectly) to the old church and especially Thomas Aquinas . Rahner justifies the belief in God as triune with the experience of God that people have through their encounter with Jesus Christ - and does not derive Christology from the doctrine of the Trinity; Christ can only be understood from the point of view of salvation history ( economics ): "The 'economic' trinity is the 'immanent' trinity and vice versa." For Rahner, this meant neither reductionism nor the possibility of deriving God's inner being from his actions. He wanted to make it clear that in the historical Jesus God himself is as present in the world as in his inner divine reality; the immanent Trinity is completely present in the economy and not behind it , even if it is inexhaustible for the human understanding .

In his writings on the doctrine of the Trinity, Rahner regularly deals with the question of the validity and meaning of the so-called psychological doctrine of the Trinity of Augustine of Hippo , the axiom of the opposing identity of the economic and immanent Trinity and the problem of the term "person" (according to Rahner, in the Trinity doctrine only the meaning of a mode of existence of a spiritual being, but not the meaning of an individual, self-conscious subject).

- Peter Knauer

Even Peter Knauer suggests the Trinity of God in the context of salvation history, namely, as the condition of the possibility of self-communication of God to the world. In view of the one-sidedness of the relation of the world to God and the thus indicative absoluteness and transcendence of God, only the doctrine of the Trinity explains how one can meaningfully speak of a real relationship between God and the world and thus of communion with God. God turns to the world with a love that is not based on the world itself, but is constituted from eternity as inner divine love. The world is taken up from the start in this love of God for God, that of the Father for the Son, which as the Holy Spirit is himself God. Only in this way is “fellowship with God” possible. And this means a last feeling of security for all people, against which no power in the world can compete, not even death. The incarnation of the Son in Jesus of Nazareth reveals this fundamental secret of faith which, because it is not proportionate to the world, cannot be recognized with mere reason. It has to be told to one through the "word of God" from Jesus and can only be recognized as true by believing in this word. But even in faith one can only speak about the Trinity of God in an indicative or “analogous way”, namely based on our own reality.

Trinity of God means that the one reality (“nature”) of God exists in three persons. Knauer understands the three divine persons as three mutually differently mediated self-presences of the one and undivided reality of God (“self-presence” means the relation of a reality to itself, as is the case with being a human being). The “father” is a first, unsanitary self-presence of God; the “Son” is a second self-presence of God, which presupposes the first and is mediated through it; the “Holy Spirit” is also God's self-presence, which presupposes the first and second self-presence and is mediated through them; he is the mutual love between father and son. One could also say that the “Father” is the “I of God”, the “Son” is the “You of God” and the “Holy Spirit” is the “We of God”. This model claims to be an alternative to tritheism and modalism , to serve ecumenical understanding and to be able to express the Trinity without logical problems. However, according to Knauer, the confession of the Triune God is only correctly understood if one realizes that it is also about our relationship with God: God has no other love than the infinite love between Father and Son, and in this love is the world of "brought in" from the start. In this view, the following applies: God's love for the finite human being is infinite and absolutely unconditional because it is identical with God himself.

Protestantism

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer

In his entire theology, Dietrich Bonhoeffer emphasized the aspect of Christian this-sidedness , justified it through the incarnation of God and the cross of Christ and radicalized this approach in the question of a religion-less Christianity beyond classical metaphysics . The “penultimate” is the “shell of the last”, only through the world does the believer come to God. In Karl Barth he criticizes a “revelatory positivism” that knows no “levels of knowledge and levels of significance”, “where it then says: 'eat, bird, or die'; Whether it is a virgin birth, the Trinity or whatever, each is an equally important and necessary piece of the whole, which must be swallowed as a whole or not at all. "On the other hand, Bonhoeffer wants to restore an arcane discipline that does not equate ultimate things with profane facts, but keeps its secret, which can only be revealed in the practice of faith in the person of Jesus. Its essence is “being-there-for-others”, and the idea of inner-divine love is bound to this central insight. In “taking part in this being of Jesus”, transcendence can be experienced in the here and now: “The transcendent is not the infinite, unattainable tasks, but the attainable neighbor that is given in each case.”

- Karl Barth

In his Church Dogmatics , Karl Barth took over from Bonhoeffer the idea of an analogia relationalis between the inner-trinitarian relationship between God, his relationship as the one God to man and the gender-specific relationship between women and men. Similar to Rahner, Barth understood God as an event of revelation, the structure of which is trinitarian: God is the subject (father), content (son) and event (spirit) of revelation. Thus the immanent (invisible) aspect is related to the economic (visible) aspect, which is also classified as neo-modalism.

Democratic secularism

The motto of the French Revolution "Freedom (son), equality (father) and fraternity (Holy Spirit)", explain representatives of the legal philosophy from the Christian tradition of the divine trinity . This political credo forms the basis of Western democracies. The preamble to the European Charter of Fundamental Rights also takes up this trinity in conjunction with the monistic idea of human dignity .

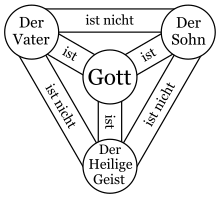

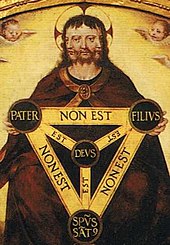

Symbolic and pictorial representations

symbolism

Analogies

The church fathers already used analogies to illustrate the Trinity, mostly with the explicit reference that they were only very imperfect images or fundamentally wrong.

- Tertullian used the images of a tree for the Trinity: roots, trunk and branches and the water that flows from the source to the stream and then to the river.

- Gregory Thaumatourgos and Augustine von Hippo compared the Trinity with the threefold gradation of the nature of man in body, soul and spirit.

- Basil of Caesarea compared the concept of the Trinity to the rainbow : sun, sunlight and colors.

- The image of three candles or torches, placed close together and burning with a single flame, can also be found with the church fathers.

- The Holy Patrick to the legend, the Irish with a shamrock have informed about the Trinity.

- More recently there is the analogy of CS Lewis , who compared the Trinity with a cube in its three dimensions.

triangle

The most famous sign of the Trinity is the triangle . It was already a symbol of the Manicheans . Nevertheless it was used further and its new Christian meaning is now to be emphasized by the insertion of the eye of God ; for many peoples the eye is a symbol of the sun god. Combinations of the Christ monogram , alpha and omega and the cross with the triangle are also known.

A further development of the triangle is the shield of the trinity .

Circles, three passport and trefoil

A geometric arrangement of three intersecting circles is often found as tracery (decorative ornamental forms) in Gothic and Neo-Gothic architecture (see graphic on the right). Both forms of tracery explained in the following can be found in many differently decorated and rotated orientations.

- In the triangle (shown in turquoise) the points of contact of the three circles with the common perimeter form an equilateral triangle - a symbol for the trinity.

- The three-leaf (shown in blue) is modeled on a leafy plant and is intended to represent the three-part unfolding of the aspects of God, i.e. the Trinity. The leaf pointing downwards symbolizes, according to isolated sources, for example Jesus as an "unfolding" from the essence of God, thus as an "expression of God" on earth. This idea can be found discussed in more detail in Cusanus .

To put it simply, one can say: The three-pass emphasizes more the unity of the three people ("trinity"), the three-leaf more their distinctiveness ("trinity"). In today's linguistic usage, however, there is usually no distinction between Trinity and Trinity.

The interpretation of three hares as symbols of the Trinity in church art is controversial.

Color mappings

The flag of Ethiopia also has a religious meaning: the colors refer to the Christian trinity. According to this, green stands for the Holy Spirit, yellow for God the Father, red for the Son. At the same time, the colors symbolize the Christian virtues hope (green), charity (yellow) and faith (red).

With Hildegard von Bingen ( Scivias ) there are mystical color assignments: The "moist green force" ( viriditas ) stands for God the Father, the son is characterized by a "purple (green) force" ( purpureus viror ).

Pictorial representations

The oldest pictorial representation is based on the typologically interpreted visit of the three men to Abraham in Mamre ( Gen 18.1–16 EU ). Three young men who look the same are shown next to each other. The earliest surviving example can be found in the catacomb on Via Latina and dates from the 4th century. Later depictions show the three men sitting at a table and add features of the angels to them. The icon of Andrei Rublev from the 15th century can be seen as the highlight of this type of image .

Another figurative representation is the depiction of the baptism of Jesus. The Father is represented by a hand and the Holy Spirit by a dove.

In the Middle Ages it is common to depict the figures of the aged father and the young son enthroned together. The Holy Spirit is represented as a dove again.

With the emerging mysticism of the Passion, the type of image of the mercy seat developed . The enthroned Father holds the cross with the crucified Son, while the Holy Spirit is represented as a dove again. The earliest surviving examples are prayer illustrations in missals, the oldest of which is in the Cambrai Missal from the 12th century. In a further development of the picture type, the father holds the dead son removed from the cross in his arms.

In addition to the passion, the birth of Jesus is also used to depict the Trinity. The aged father and the holy spirit as a dove are happy about the son shown as an infant. An example of this is the depiction of the Nativity in the church of Laverna from the 15th century.

In folk art, representations of the Trinity also develop as a figure with three heads or with a three-faced head (tricephalus) . This representation is rejected by the ecclesiastical authority as incompatible with the faith. B. by the prohibition of the representation of the Tricephalus by Pope Urban VIII in the year 1628.

A special variant is the depiction of the Holy Spirit as a feminine youth, for example on a ceiling fresco in the St. Jakobuskirche in Urschalling near Prien am Chiemsee from the 14th century. or in the pilgrimage church Weihenlinden in the 18th century, based on vision reports by Maria Crescentia Höss from Kaufbeuren. Such a representation was then forbidden by Benedict XIV with the decree Sollicitudine Nostrae of 1745.

Holy Trinity and Patronage

The feast of the Holy Trinity ( Sollemnitas Sanctissimae Trinitatis ) is celebrated in the Western Church on the Sunday after Pentecost , the Sunday Trinity . In the Eastern Church, the feast of Pentecost is itself the feast of the Trinity. The Sundays from the Holy Trinity to the end of the church year - the longest period in the church year - are referred to in the Protestant Church as Sundays after Trinity .

Numerous churches and monasteries are consecrated or dedicated to the Trinity.

distribution

Most of the religious communities referring to the Christian Bible follow the Trinitarian dogma. Both the Western (Roman Catholic and Protestant) and Eastern (Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox) churches have consistently represented the doctrine of the Trinity since the end of the 4th century.

At the present time the Trinity is listed in the constitution of the Ecumenical Council of Churches and is thus recognized by all affiliated churches (Orthodox, Anglican, larger Protestant) and also by the Roman Catholic Church. The confession of the Trinity is also one of the foundations of faith in the evangelical movement.

For non-Trinitarian Christian movements, see Non-Trinitarian .

Opposite position in Judaism and Islam

Jewish belief

The Jewish faith has no trinity. It contradicts the central Jewish idea of the Shema Yisrael , the Toraver of a single God in a "form" elementary. The spirit (in Hebrew ruach ) is understood as God's breath of life. In this belief, the expected Meschiah ( German Messiah) is also a person, possibly with special gifts or charisms . In the person of Jesus of Nazareth , the Jewish faith does not see a person of the Trinity, but only a Jewish traveling preacher (as there were many during Jesus' lifetime) who spread Jewish ideas and was executed by the Roman occupying power for rebellion. According to the Talmud , Jesus ends up in hell .

Islam

Classical Islamic theology ( Ilm al-Kalam ) understands the Christian doctrine of the Trinity as incompatible with the oneness of God ( Tawheed ) and as a special case in which one god is "added" to another ( Shirk ).

“God does not forgive that one associates (other gods) with him. What lies below (that is, the less grave sins) he forgives, if he wills (forgive). If one (one) associates (other gods) with God, he has hatched a huge sin. "

Today's Islamic intellectuals only occasionally deviate from this assessment, for example to argue that the Koran only rejects a misunderstanding of the Christian trinity, namely a belief in the three gods ( tritheism ). In the Koran , the Christian idea of the Trinity is understood as the trinity of God, Jesus and Mary . Mary is therefore part of the Trinity and is worshiped as God by Christians. In more recent Islam research, however, a different approach has been taken. So David Thomas describes those verses in the direction that here less a literal creed that Mary is part of the Trinity is discussed, rather this verse is about a reminder to humanity to venerate Jesus or Mary excessively. Gabriel Said Reynolds, Sidney Griffith, Angelika Neuwirth and Mun'im Sirry argue similarly; According to Sirry & Neuwirth, this is primarily about making a rhetorical statement in the language of the Koran. In addition, there are references in the sources to an early Christian sect in which Mary was deified.

“And when God said: 'O Jesus, Son of Mary, was it you who said to the people:' Take me and my mother as gods next to God '?"

According to Ayatollah Dastghaib Shirazi, Christians belong, from an "Islamic point of view [...] in a certain way to the polytheists " ( Muschrik ), because they believe in the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The father is identified today with Allah / God , the son with Isa / Jesus and the Holy Spirit with Jibril / angel Gabriel . The Koran says in relation to these people:

“Those who say: 'God is one of three' are unbelievers. There is no god but one god. And if they don't stop what they say (there) (they have nothing good to expect). Those of them who disbelieve will (one day) face a painful punishment. "

Isa / Jesus is by no means God's Son for Muslims - except in the context that all believers are non-bodily children of God - since God is the creator of all being anyway. For Muslims this is blasphemy , because putting someone next to God is the worst crime for Muslims for which there is no forgiveness ( shirk ). However, Mary is not counted as a Trinity in any Christian church or special community. The reason for the differing understanding of Islam could have been a misunderstanding of Christian devotion to Mary or the acquaintance of Muhammad with triadic ideas of neighboring peoples in the east. The explanation seems more likely that the Semitic word for “spirit” is feminine (Hebrew / Aramaic: רוח, ruach). This could lead to the misconception that we are talking about God the Father, God Mother and God the Son. However, as noted above, recent Islamic research advocates the thesis that understanding is not based on a misunderstanding, but rather is used specifically as a stylistic means to use rhetoric to warn of the dangers of deifying Jesus. According to Angelika Neuwirth & Mun'in Sirry, this “Koranic passage can be understood as a rhetorical statement”, since in recent Islam research the “focus is on the rhetorical language of the Koran”. The trinity is explicitly rejected in the Quran in the following places, among others:

“Christ Jesus, the Son of Mary, is only the Messenger of God and his Word, which He brought over to Mary, and a spirit from him. So believe in God and His Messengers. And don't say: three. "

"He [God] did not create, and He was not created."

Christian theologians counter, on the one hand, that this “very physical” conception of the Trinity does not correspond to the Trinity as it is understood by Christianity, which emphasizes the absolute spirituality of God: The Son is begotten by the Father not in a physical but in a spiritual way. In the same way, the Holy Spirit emerges in a spiritual way - according to the western church view from the love of father and son (acceptance of the Filioque ), according to the eastern church view from the father (rejection of the Filioque). Islamic theologians, on the other hand, point out that this question is of subordinate importance, since, according to Islamic understanding, even the invocation of Jesus, for example, falls into the category of shirk (often translated as polytheism in German ).

Extra-Christian triadic ideas

Divine triads (triads, i.e. three different deities belonging together), often consisting of father, mother and child, are known from most mythologies , for example in Roman mythology Jupiter , Juno and Minerva or Osiris , Isis , and Horus in Egyptian mythology .

Even vague "beginnings of ... Trinity" have been traced back to Egyptian theological tradition.

There are also triads with the concept of modalism : a deity appears in different (often three) forms: For example, pre-Christian goddesses in Asia, Asia Minor and Europe (such as the Celtic Morrígan or the matrons ) were often three different people depicted: as a virgin ("goddess of love"), as a mother ("fertility goddess") and as an old woman ("death goddess") - each responsible for spring, summer and winter - all manifestations of the same goddess. In Neopaganism it became a triune goddess .

Hinduism

In Hinduism, a Trimurti (“three figure”, “three-part idol”) is the unity of the three aspects of God in his forms as creator Brahma , as sustainer Vishnu and destroyer Shiva . This trinity in the unity ( trimurti ) represents the formless Brahman and expresses the creating, sustaining and destroying aspects of the highest being, which condition and complement one another. Whether these are "persons" in the Christian sense depends on the conception of the respective theological tendency of "person": In the case of pantheistic tendencies such as the Shankaras , the question is superfluous; Directions that emphasize personality like the Ramanujas or Madhvas tend to subordinate the three aspects as a kind of "archangel" to a transcendent deity like Vishnu or Shiva. Especially in Tamil Shaivism , Shiva is seen as a transcendent God and his destructive function is called Rudra . Sometimes one also counts delusion and redemption to the (now five) main aspects of Shiva, which are then symbolically represented in the image of the dancing Shiva .

However, the Trimurti is not a central concept of Hinduism, because there are also "two-form" images, above all the widespread representation of Shiva as half man and half woman ( Ardhanarishvara ), the also very common Harihara image, the half Vishnu and is half Shiva, and in which the now little revered Brahma is missing. Another group of gods, which can also be understood as a higher unit, is Shiva and Parvati with their children Ganesh and / or Skanda as a family of gods.

Shakti worshipers, the followers of the female form of God, also know a female Trimurti with Sarasvati - the creator, Lakshmi - the sustaining and Kali - the destroyer.

Buddhism

The Zen Buddhism distinguishes a triple Buddha body ( Trikaya ):

- Dharma-kāya, which represents the essence of the Buddha and exists forever;

- Saṃbhoga-kāya, who represents the aspect of possibility and wants to lead all people to salvation through the connection of compassion and wisdom;

- Nirmāna-kāya, which means the appearance of the Buddha in the world.

The central figure in Mahayana Buddhism is the Saṃbhoga-kāya. It corresponds to the idea of the Bodhisattva , which is possible not only for Buddha himself, but for all people.

For the world this means:

- Viewed in the light of the Dharma-kāya Buddha, the world (viewed with the eye of enlightenment) is identical to this: "Whoever knows the four noble truths perceives Dharma-kāya Buddha in every corner of the world."

- Viewed in the light of the Nirmāna-kāya Buddha, the world is the object of salvation. Buddha appears in the world of suffering because he cannot forsake those who suffer. The appearance or non-appearance of the Buddha depends on the current state of the world.

- Contemplated in the light of the Saṃbhoga-kāya Buddha, the world is the place of probation on the Buddha's Middle Path . The Bodhisattva walks both the path of salvation (the path down) and the path of enlightenment (the path up).

Living in this world means being in between between the banks of suffering and the banks of redemption. The bodhisattva loves to live in this world of sunyata . Sunyata does not simply mean emptiness, but also abundance, co-existence without any rejection or avoidance. The Saṃbhoga-kāya Buddha understands that the world of suffering is nothing but the world of enlightenment.

Man's relationship to truth (love) becomes clear in the picture story of the ox and his shepherd . In ten pictures, a story of searching, finding, taming, forgetting, losing oneself and finding new ones is told, which makes it clear how much Buddhism is a spiritual exercise, a way of (self) knowledge.

Gnosis

Triadic or trinitarian formulations can also be found in the Gnostic texts of Nag Hammadi .

Neoplatonism

The philosophy historian Jens Halfwassen considers it one of the strangest ironies in history that “of all people Porphyry, the declared enemy of Christians, with his Trinitarian concept of God, which he developed from the interpretation of the Chaldean oracles , became the most important stimulus for the formation of the church dogma of the Trinity in the 4th century ... It was Porphyry of all people who had taught the orthodox church fathers how one can think of the mutual implication and thus the equality of three different moments in God with the unity of God, which made the divinity of Christ compatible with biblical monotheism. " However, the Incarnation of one of the Persons of the Trinity was unacceptable to a Neoplatonist like Porphyry.

literature

Dogma and Church History

- Leonardo Boff : Small doctrine of the Trinity. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-491-69435-4 .

- Christoph Bruns: Trinity and Cosmos. To Origen's doctrine of God. Adamantiana Vol. 3, Aschendorff, Münster 2013, ISBN 978-3-402-13713-0 .

-

Franz Courth : Trinity (= handbook of the history of dogma , vol. 2: The trinitarian God - the creation - the sin , fascicle 1). Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau

- Fascicle 1a: In der Schrift und Patristik , 1988, ISBN 3-451-00745-2 .

- Fascicle 1b: In der Scholastik , 1985, ISBN 3-451-00744-4 .

- Fascicle 1c: From the Reformation to the Present , 1996, ISBN 3-451-00741-X .

- Franz Dünzl: Small history of the Trinitarian dogma in the old church. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2006, ISBN 3-451-28946-6 .

- Peter Gemeinhardt : The Filioque Controversy between Eastern and Western Churches in the Early Middle Ages. Dissertation University of Marburg 2001. Works on Church History Vol. 82, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-11-017491-X .

- Jan Rohls : God, Trinity and Spirit. The history of ideas of Christianity vol. 3, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-16-152789-0 .

Systematic theology

- Gisbert Greshake : The Triune God. A trinitarian theology. Special edition, 5th, further expanded edition of the first edition. Herder, Freiburg (Breisgau) a. a. 2007, ISBN 978-3-451-29667-3 .

- Gisbert Greshake: Believe in the three-one god. A key to understanding. Herder, Freiburg (Breisgau) a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-451-26669-5 .

- Matthias Haudel: Doctrine of God. The meaning of the doctrine of the Trinity for theology, church and world. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht / UTB, Göttingen 2015, 2nd edition 2018, ISBN 978-3-8252-4970-0 .

- Matthias Haudel: The self- disclosure of the Triune God. Basis of an ecumenical understanding of revelation, God and the church. (= Research on systematic and ecumenical theology 110) Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, double edition, ISBN 978-3-525-56338-0 .

- Klaus Hemmerle : Theses on a Trinitarian Ontology. Johannes-Verlag, Einsiedeln 1976, ISBN 3-265-10171-1 .

- Jürgen Moltmann : Trinity and Kingdom of God. To the doctrine of God. 3. Edition. Kaiser, Gütersloh 1994, ISBN 3-579-01930-9 .

- Daniel Munteanu: The comforting spirit of love. On an ecumenical teaching of the Holy Spirit on the Trinitarian theologies of Jürgen Moltmann and Dumitru Staniloaes. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2003, ISBN 3-7887-1982-6 (also: Heidelberg, Univ., Diss., 2002).

- Bernhard Nitsche : God and Freedom. Sketches for the Trinitarian doctrine of God (ratio fidei 34). (Blow) Regensburg 2008

- Karl Rahner (Ed.): The one God and the three God. The understanding of God among Christians, Jews and Muslims. Schnell and Steiner, Munich a. a. 1983, ISBN 3-7954-0126-7 .

- Joseph Ratzinger : Belief in the Triune God. In: Joseph Ratzinger: Introduction to Christianity. Lectures on the Apostles' Creed. With a new introductory essay. Completely unchanged, new edition with a new introduction. Kösel, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-466-20455-0 , chapter 5.

- Hartmut von Sass: Post-metaphysical Trinity - Barth, Jüngel and the transformation of the doctrine of the Trinity. In: ZThK , Heft 3, 2014, ISSN 0044-3549 , pp. 307–331.

- Bertram Stubenrauch : Dreifaltigkeit (= Topos-plus-Taschenbücher vol. 434 positions ). Matthias Grünewald Verlag, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-7867-8434-5 .

- Heinz-Jürgen Vogels : Rahner cross-examined. Karl Rahner's system thought through. Borengässer, Bonn 2002, ISBN 3-923946-57-0 .

- Herbert Vorgrimler : God - Father, Son and Holy Spirit. 2nd Edition. Aschendorff, Münster 2003, ISBN 3-402-03431-X .

- Michael Welker , Miroslav Volf (ed.): The living God as a trinity. Jürgen Moltmann on his 80th birthday. Gütersloher Publishing House, Gütersloh 2006, ISBN 3-579-05229-2 .

- Rudolf Weth (Ed.): The living God. On the trail of more recent Trinitarian thinking. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2005, ISBN 3-7887-2123-5 .

Web links

Current introductory presentations

- Dale Tuggy: Trinity. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- HE Baber: Trinity. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Anne Hunt: The Development of Trinitarian Theology in the Patristic and Medieval Periods (PDF; 202 kB); in: Anne Hunt: Trinity ; Orbis, New York 2005, pp. 5-34.

Older introductory presentations

- George Joyce: The Blessed Trinity . In: Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company, New York 1913.

- Otto Kirn : Doctrine of the Trinity , in: SM Jackson, GW Gilmore (Eds.): The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge , Vol. 12, Baker House, Grand Rapids, Michigan 1950, pp. 18-23.

- Joseph Pohle : The divine Trinity , Herder, Freiburg-London 1912.

- BB Warfield : Trinity , in: International Standard Bible Encyclopedia 1915.

More specific secondary literature

- Karl-Heinz Ohlig : One or three? From “Father Jesus” to the Trinity (X). Imprimatur, 1998/2 ( Memento from June 12, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

Bibliographies

- Information Philosophy (Ed.): Selected Bibliography Part 1 , Part 2

- Herbert Frohnhofen : Selected Bibliography

- Peter Godzik : From God. A Reader on the Trinity , 2015 (online at pkgodzik.de)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Helmuth von Glasenapp : The five world religions Munich 2001 (Diederichs Yellow Row 170) p. 232.

- ↑ According to Thomas Söding , Art. Trinity, I. Biblical-theological, in: LThK 3 Volume 10, Sp. 239–242, here Sp. 241

- ↑ See introductory James H. Charlesworth : The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon 2008, ISBN 0-687-02167-7 .

- ↑ Jürgen Werbick , for example, offers a contemporary methodological orientation in this regard : Trinity doctrine. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik , Volume 2. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2000, pp. 481–574, here pp. 484–486.

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600), Volume 1: The Christian Tradition. A History of the Development of Doctrine , chapter The Mystery of the Trinity ; 1971

- ↑ Friedrich-Wilhelm Marquardt : How does the Christian doctrine of the Triune God relate to the Jewish emphasis on the unity of God? In: Frank Crüsemann, Udo Theissmann (ed.): I believe in the God of Israel . Gütersloh 2001; Moses Maimonides, A cross-section through his work, Cologne 1966, p. 97.

- ↑ So at least F. Courth: Trinity, 2. Christian. In: Adel Theodor Khoury (ed.): Lexicon of basic religious terms. Graz u. a. 1996; Sp. 1075-1079, here Sp. 1076.1078.

- ↑ Söding, lc, column 241.

- ↑ Werbick 2000, lc, 488

- ↑ Cf. Joachim Gnilka : Das Matthäusevangelium, Herder's theological commentary on the New Testament, Vol. 1/1, 78 and 1/2, 509

- ↑ Cf. Joachim Gnilka : The Gospel of Matthew (Herder's theological commentary on the New Testament, Vol. 1/2). P. 509.

- ↑ in Mt 3,13–17 EU (cf. also Mk 1,9–11 EU , Lk 3,21–22 EU , Joh 1,32–34 EU )

- ↑ Cf. Gnilka, lc Careless, for example Michael Schmaus : Trinity. In: Heinrich Fries (ed.): Handbook of theological basic concepts. Kösel, Munich 1962, pp. 264–282, here p. 267.

- ^ Söding, lc; Werbick 2000, lc, p. 490.

- ↑ As in Acts 2.38 EU , Acts 8.16 EU , Acts 10.48 EU , Acts 19.5 EU .

- ↑ Even earlier, dated to around AD 60–65 by Klaus Berger : The New Testament and early Christian writings . Insel, Frankfurt / M., Leipzig 1999, p. 302.

- ↑ Didache 7.

- ^ Franz Graf-Stuhlhofer : Jesus Christ - God's Son . Leun 3 2012, pp. 18-20.

- ↑ See Söding: Trinity , Col. 240.

- ↑ Cf. Mt 11.27 EU , Lk 10.22 EU

- ^ Horst Georg Pöhlmann : Abriß der Dogmatik. Gütersloh, 4th edition 1973, p. 236: "The NT designates Jesus as God (Joh 1,1; 20,28; Heb 1,8-10; Kol 2,2) and godlike being (Phil 2,6), he is worshiped like a god (1 Cor 8: 6), ... "

- ↑ Further passages are mentioned in Graf-Stuhlhofer: Jesus Christ - God's Son , 2012, pp. 39–41, namely Joh 1,1 EU , Röm 9,5 EU , Hebr 1,8-10 EU , 2 Petr 1,1 EU .

- ↑ That Jesus speaks here can be seen from Rev 22: 12 and 20 . Further equations discussed at Graf-Stuhlhofer: Jesus Christ - God's Son , pp. 24–31.

- ↑ Lk 1.35 EU and Mt 1.20 EU

- ↑ cf. Mk 1.9 EU ff; Lk 4,14.16-21 EU , Acts 10,38 EU

- ↑ cf. 1 Cor 15.45 EU , 2 Cor 3.17 EU , Rom 5.8 EU

- ↑ Joh 14,16,26 EU ; 15.26 EU ; 16.7 EU ; see. again z. B. Söding, lc and Werbick 2000, lc, pp. 487-490.

- ↑ For Basilius this statement becomes the core part of his theology of the divinity of the Holy Spirit ( On the Holy Spirit , Chapter IX).

- ↑ Did 7.1 (see above); Justin 1 Apol 61,3, Irenäus Adv. Haer. 3,17,1, Tertullian Adv. Prax. 26.9.

- ↑ For example in Hippolytus, DH 10; see. Werbick 2000, lc, 491

- ↑ Cf. Justin, 1 Apol 65,3, Hippolyt, Apost. Trad. 4th

- ↑ Justin, 1 Apol. 65.67; Basil. De Spir. 2-6; Apost. Trad. 4th

- ^ Irenaeus, Adv. Haer. 1.10 / 22.1

- ↑ 1 Apol. 6.2; 13.3; 61,3.10; 65.3; 67.2.

- ↑ Cf. u. a. Adv. Haer. 4.20.1.

- ↑ See Werbick 2000, 493.

- ↑ Or. 13, 6; see. Werbick 2000, 493

- ^ Wolf-Dieter Hauschild , Volker Henning Drecoll : Textbook of Church and Dogma History. Volume 1. Old Church and Middle Ages . Gütersloher Verlagshaus , Gütersloh 2016, p. 62. 5., completely revised new edition.

- ↑ Richard Weihe: The paradox of the mask: history of a form . Fink, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3770539147 , p. 192.

- ^ Hanns Christof Brennecke , Annette von Stockhausen, Christian Müller, Uta Heil, Angelika Wintjes (eds.): Athanasius works. Third volume, first part. Documents on the history of the Arian dispute. 4th delivery: Up to the Synod of Alexandria 362 . Walter de Gruyter , Berlin / Bosten 2014, p. 594ff.

- ↑ after Jaroslav Pelikan, lc

- ^ Giuseppe Alberigo (ed.): History of the Councils. From the Nicaenum to Vatican II . Fourier, Wiesbaden 1998, p. 29-31 .

- ^ Andreas Werckmeister: Musical Paradoxal Discourse. Calvisius, Quedlinburg 1707 pp. 91-97 [1] ; Plüss, David; Jäger, Kirsten Andrea Susanne; Kusmierz, Katrin (Ed.): How does reform sound? Works on liturgy and music. Collected essays by Andreas Marti. Practical theology in the Reformed context: Vol. 11. Zurich: Theologischer Verlag Zurich 2014, p. 94f.

- ↑ Leonardo Boff: The Triune God . Patmos, Düsseldorf 1987, v. a. Pp. 173-179.

- ^ Joseph Ratzinger: Introduction to Christianity ; Munich 1968. ISBN 3-466-20455-0 .

- ^ William McDonald (Ed.): New Catholic Encyclopedia , Article Trinity ; New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967; P. 295

- ^ Trinity, Holy (In the Bible) , in: New Catholic Encyclopedia , New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967.

- ↑ See Summa Theologiae I, q. 43 a. 4 ad 1: “pater dat seipsum, inquantum se liberaliter communicat creaturae ad fruendum”; Summa Theologiae I, q. 106 a. 4 c .: "omnes creaturae ex divina bonitate participant ut bonum quod habent, in alia diffundant, nam de ratione boni est quod se aliis communicet" u. ö.

- ↑ Karl Rahner: The triune God as the transcendent source of salvation history . In: Mysterium Salutis II (1967), p. 328.

- ↑ On Rahner's doctrine of the Trinity, cf. Michael Hauber: Inexpressibly close. A study on the origin and meaning of Karl Rahner's doctrine of the Trinity. Innsbruck 2011 (ITS 82).

- ↑ Peter Knauer: The one that proceeds from the father and the son. Retrieved August 7, 2018 .

- ^ Letter to Eberhard Bethge of May 5, 1944; in: Resistance and Surrender ; Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1978 10 , p. 137

- ↑ draft of a work; in: Resistance and Surrender ; Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 1978 10 , p. 191f.

- ^ New Catholic Encyclopedia , Vol. 14, Art. Trinity, Holy; Detroit: Thomson / Gale, 2003 2 ; P. 197

- ↑ Hans – Martin Pawlowski: Protection of life. On the relationship between law and morality. In: Kurt Seelmann (Hrsg.): Current questions of legal philosophy . 2000, p. 9 ff., 21; Axel Montenbruck : civil religion. A legal philosophy I. Foundation: Western “democratic preamble humanism” and universal triad “nature, soul and reason” . University Library of the Free University of Berlin, 3rd extended edition, 2011, p. 106 ff, ( open access )

- ^ John Roach, St. Patrick's Day Facts: Snakes, a Slave, and a Saint ; National Geographic News, March 16, 2009.

- ^ I. Schwarz-Winklhofer, H. Biedermann: The book of signs and symbols ; Wiesbaden: fourier, 2006; ISBN 3-932412-61-3 ; P. 110

- ↑ Ute Mauch: Hildegard von Bingen and her treatises on the Triune God in ' Liber Scivias ' (Visio II, 2). A contribution to the transition from speaking pictures to words, writing and pictures. In: Würzburger medical history reports 23, 2004, pp. 146–158; here: pp. 152–157 ( The representation of the Trinity in Visio II, 2 ).

- ↑ Illustration of the fresco by Jürgen Kuhlmann: Christian idea basket for mature stereo thinking . Evamaria Ciolina: The Urschalling fresco cycle. History and iconography ; Miscellanea Bavarica Monacensia 80 / Neue Schriftenreihe des Stadtarchiv München 101; Munich: Commission bookstore R. Wölfle, 1980; ISBN 3-87913-089-2 . Barbara Newman: From virile woman to woman Christ. Studies in medieval religion and literature ; University of Pennsylvania Press 1995; ISBN 0-8122-1545-1 ; P. 198 ff.

- ↑ See François Boespflug: Dieu dans l'art: sollicitudine Nostrae de Benoit XIV et l'affaire Crescence de Kaufbeuren . Les Editions du Cerf, Paris 1984, ISBN 978-2-204-02112-8

- ↑ “Again it is reserved for the Babylonian Talmud to bring a counter-narrative to the message of the New Testament. In fact, it offers the exact opposite of what the New Testament proclaims, namely a highly drastic and bizarre story about Jesus' descent into hell and the punishment that befell him there. " Peter Schäfer: Jesus in the Talmud . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2010, ISBN 978-3161502538 , p. 167 ff.

- ↑ Nils Horn: Islam basic knowledge . BookRix, January 9, 2017, Section 7 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Rudi Paret : The Koran . 12th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-17-026978-1 , pp. 65 .

- ↑ Cf. William Montgomery Watt , AT Welch: Der Islam , Vol. 1; Stuttgart 1980, 126f

- ^ AJ Wensinck, in: sv MARYAM ; in: AJ Wensinck, JH Kramers (ed.): Handwortbuch des Islam , Leiden: Brill 1976, p. 421 f .; Rudi Paret in the commentary on his translation of Sura 5, 116; in: The Koran, Commentary and Concordance ; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart 1971, p. 133; Wilhelm Rudolph: The Koran's dependence on Judaism and Christianity ; Stuttgart 1922, p. 86f .; Adel Theodor Khoury: Islam and the Western World ; Darmstadt 2001, p. 80; William Montgomery Watt: Islam , Vol. 1: Mohammed and the early days. Islamic law, religious life ; The Religions of Mankind 25; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart u. a. 1980; P. 127.

- ↑ David Thomas: Encyclopedia of the Quran, Section: Trinity .

- ^ Qur'ānic Studies Today, by Angelika Neuwirth, Michael A Sells . S. 302 : "It can be argued that it is not at all impossible that the quranic accusations that christians claim Mary as God can be understood as a rhetorical statement."

- ↑ Scriptural Polemics: The Qur'an and Other Religions, by Mun'im Sirry . 2014, p. 47 ff . "In more recent scholarship of the Quran, as represented by the works of Hawting, Sidney Griffith and Gabriel Reynolds, there is a shift from the heretical explanation to the emphasis on the rhetorical language of the Quran. When the Quran states that God is Jesus the son of Mary [...] it should be understood as [...] statements. Griffith states, "the Quran's seeming misstatement, rhetorically speaking, should therefore not thought to be a mistake, but rather [...] a caricature, the purpose of which is to highlight the absurdity and wrongness of christian belief, from in Islamic terms an islamic perspective. "[...] Reynolds persuasively arguments that" in passages involving christianity in the Quran, we should look for the Quran's creative use of rhetoric and not for the influence of christian heretics. ""

- ↑ Angelika Neuwirth: Qur'ānic Studies Today . ISBN 978-1-138-18195-3 , pp. 300-304 .

- ^ Ibid . S. 301 : "The Collyridians, an arabian female sect of the fourth century, offered Mary cakes of bread, as they had done to their great earth mother in pagan times. Epiphanius who opposed this heresy, said that the tri ity must be worshiped but Mary must not be worshiped. "

- ↑ a b c Ayatollah Dastghaib Shirazi - translated by Hessam K .: The first greatest sin in Islam - Shirk. In: al-shia.de. The Shia, accessed March 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Rudi Paret : The Koran . 12th edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-17-026978-1 , pp. 87 .

- ↑ Art. "Jesus [isa] (a.)", Eslam.de.

- ↑ Differentiation of Islam from Christianity and Judaism - The main differences in the religions. In: religion ethik religion-ethik.de. Association for Social Life eV, accessed on March 16, 2019 .

- ^ Qur'ānic Studies Today, by Angelika Neuwirth, Michael A Sells. P. 302: “It can be argued that it is not at all impossible that the quranic accusations that christians claim Mary as God can be understood as a rhetorical statement. In more recent scholarship of the Quran, as represented by the works of Hawting, Sidney Griffith and Gabriel Reynolds, there is a shift from the heretical explanation to the emphasis on the rethorical language of the Quran. "

- ↑ a b c d Dr. Martin Weimer: The Islamic misunderstanding of the Trinity as a belief in the three gods. In: Trinity. Kath. Pfarramt Altdorf, accessed on March 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Nils Horn: Islam basic knowledge . BookRix, January 9, 2017, Section 7 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ E. Hornung: The Beginnings of Monotheism and the Trinity in Egypt ; in: K. Rahner (Ed.): The one God and the three God. The understanding of God among Christians, Jews and Muslims ; Freiburg im Breisgau 1983; Pp. 48-66

- ↑ Peter Godzik : Report on the joint meeting of the LWF working group “On Other Faiths” and the VELKD working group “Religious Communities” from 11-15. April 1988 in Pullach (online at pkgodzik.de)

- ↑ Cf. Alexander Böhlig : Triad and Trinity in the writings of Nag Hammadi . In: Alexander Böhlig: Gnosis and Syncretism. Collected essays on the history of religion in late antiquity. 1st chapter; Tübingen 1989, pp. 289-311; Alexander Böhlig: On the concept of God in the Tractatus Tripartitus. In: Gnosis and Syncretism , pp. 312-340.

- ↑ Jens Halfwassen: Plotinus and Neo-Platonism . Munich 2004, p. 152.