Trinity (Masaccio)

|

| Trinity |

|---|

| Masaccio , 1425 to 1428 |

| fresco |

| 667 × 317 cm |

| Santa Maria Novella |

The Trinity is a fresco in the Santa Maria Novella church in Florence . It was created by Masaccio between 1425 and 1428 . It is considered to be groundbreaking for European art, as it was the first time in painting that an artist correctly applied the laws of perspective .

History of origin

The fresco was donated by two people also depicted on the fresco, a man and a woman. Possibly the donors were among the recognized Florentine personalities in the first quarter of the 15th century. The picture was created in the period from 1425 to 1428, different years are mentioned within this range. Masaccio had previously learned how to represent perspective from Brunelleschi , the real discoverer of the central perspective .

technology

Masaccio first laid down the rough outlines and contours of the fresco with a preliminary drawing on the rough plaster. In the chosen vanishing point of perspective, which is at eye level with a standing adult, he hammered in a nail and fastened cords to it, which he stretched in the desired direction of perspective. He pressed the resulting lines into the fresh, fine lime plaster that was applied or scratched them with a stylus. These traces can still be seen in the fresco today. Only then could he begin the actual painting. As with most fresco work, the entire picture could not be created in one day, he worked it off in so-called day works ( giornata ). The fresco technique requires precise planning, precisely because the paint can only be applied to damp plaster. It took him about a month to complete the entire fresco.

presentation

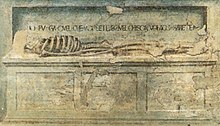

The fresco consists of two parts that are related to each other. The upper part includes the crucified Jesus , the lower shows the image of a skeleton on a sarcophagus and a motto. While the upper part remained visible over the centuries, the lower part was covered by an altar added in the 16th century. This was only removed after the Second World War, and this part of the fresco was rediscovered.

The architectural representation

Masaccio chose a coffered barrel vault supported by four columns with Ionic capitals as the background depicted in point perspective . The outer frame of the fresco is made up of two huge, fluted pilasters with composite capitals that support a detailed architrave . The two front columns with the round arch and the pilasters, the architrave and the rosettes in between have the appearance of an ancient Roman triumphal arch , which is seen as an indication of the triumph of Christ over death.

The people pictured

The upper half of the fresco initially contains a representation of the Trinity . Christ is depicted as crucified, behind him God holds the crucifix. Masaccio depicts him floating freely in space from below, which is seen as a “bold attempt”. The dove, the symbol of the Holy Spirit, hovers above the head of the crucified . Masaccio placed Mary next to the crucifixion scene on the left . She is the only person in the picture who makes a movement, her right hand points to the son, while her gaze is directed out of the picture, but not directly at the viewer. This is seen as an indication of the connection between the divine and human world. The evangelist John is depicted on the right . One step below, in front of the pilasters, the donor figures kneel, a man around 50 years old in a red cloak and a woman with a black hood and a blue robe. You're looking directly at each other, so it's probably a married couple. They were deliberately shown separated from the sacred space of the crucifixion scene. All figures are represented "harshly realistic" because Masaccio had detailed anatomical knowledge. He had acquired this from his contemporary Donatello .

The lower part contains the representation of a skeleton on a sarcophagus . Above the skeleton is the saying: “ Io fu già quel che voi siete, e quel chi son voi anchor sarete ” (“I was what you are, and what I am, you will be”) to read, one at a time frequently encountered memento mori . It is Adam's skeleton on the Crucifixion Mount Golgotha . Ultimately, the entire iconography of the picture revolves around the implementation of the Golgotha chapel in Jerusalem . This was not uncommon at that time, efforts were made to bring the holiness of the holy places into their own city by depicting the holy places.

The illustration repeats and deepens the message of the entire picture: Only those who pray to God and receive the intercession of Mary and the saints will experience salvation.

In terms of the structure of the picture, the figures represent a pyramid, which forms the compositional contrast to the inverted triangle of the central perspective behind. The vanishing point is in the middle of the lower edge of the upper fresco. From this vanishing point, another compositional triangle goes into the lower half of the fresco, over the outer edges of the sarcophagus to the corners of the lowest picture strip.

As a further notable innovation, all figures, both the donors and the acting saints, are depicted on the same scale and not graded according to their spiritual significance, as was the case in the Gothic period.

aftermath

The picture has had an after-effect on European art to this day. Immediately afterwards , artists like Paolo Uccello took over perspective; it was further developed a little later by Fra Angelico and also became important for Filippo Lippi's work . The lifelike anatomy of the representation was adopted and expanded by, for example, Castagno or Domenico Veneziano . Giorgio Vasari wrote about the fresco: "In addition to the figures, a barrel vault is very beautiful in this picture, divided into fields and rosettes, which taper in such correct perspective that they seem to recede through the wall into the depths." Wundram writes: "Never before in occidental painting has a space constructed with such precise perspectives been so precisely reproduced."

Individual evidence

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures , p. 20

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 245

- ↑ on this in detail: Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 106

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 245

- ^ Zuffi, Die Renaissance , p. 94

- ^ Zuffi, Die Renaissance , p. 94

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 245

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures . P. 21

- ↑ Grote, Florence - Shape and History of a Community , p. 157

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures , p. 21

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures , p. 21

- ↑ Semrau, The Art of the Renaissance in Italy and in the North , p. 163

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures . P. 21

- ^ Zuffi, Die Renaissance , p. 94

- ^ Woermann, Italian portrait painting of the Renaissance , p. 39

- ^ Woermann, Italian portrait painting of the Renaissance , p. 39

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures , p. 20

- ^ Stützer, Painting of the Italian Renaissance , p. 74

- ↑ quoted from Stützer, Painting of the Italian Renaissance , p. 74

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures , p. 21

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 246

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 246

- ↑ de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures , p. 21

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 247

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 247

- ↑ Wolf / Millen, Birth of the Modern Era , p. 17

- ↑ Toman (Ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance , p. 247

- ^ Cleugh, The Medici , p. 225

- ↑ quoted in Stützer, Painting of the Italian Renaissance , p. 74

- ↑ Manfred Wundram: Renaissance , p. 46.

literature

- Rolf Toman (ed.), The Art of the Italian Renaissance - Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Drawing , Tandem Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8331-4582-7 .

- Max Semrau, The Art of the Renaissance in Italy and in the North , 3rd edition, Vol. III from Wilhelm Lübke, Grundriss der Kunstgeschichte , 14th edition, Paul Neff Verlag, Esslingen 1912.

- Patrick de Rynck, The Art of Reading Pictures - The Old Masters Deciphering and Understanding , Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-86601-695-6 .

- Andreas Grote, Florence - Shape and History of a Community , 5th edition, Prestel Verlag, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-7913-0511-5 .

- Karl Woermann, The Italian Portrait Painting of the Renaissance , Vol. 4 of the series of guides to art , ed. by Hermann Popp, Paul Neff Verlag (Max Schreiber), Esslingen 1906.

- Herbert Alexander Stützer, Painting of the Italian Renaissance , DuMont's Library of Great Painters, DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne 1979, ISBN 3-7701-1118-4 .

- James Cleugh, The Medici - Splendor and Power of a European Family , 2nd edition, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-423-10318-3 .

- Stefano Zuffi, The Renaissance - Art, Architecture, History, Masterpieces , DuMont Buchverlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8321-9113-9 .

- Robert E. Wolf / Ronald Millen, Birth of the Modern Era , Art im Bild series, Naturalis Verlag, Munich, ISBN 3-88703-705-7 .

- Manfred Wundram : Renaissance , Art Epochs Vol. 6, Reclam, 2004, ISBN 3-15-018173-9 .