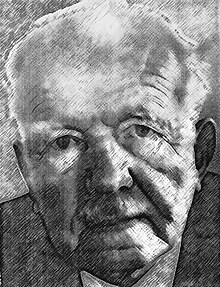

Eduard Spranger

Eduard Spranger (born June 27, 1882 as Franz Ernst Eduard Schönenbeck in Lichterfelde , Berlin ; † September 17, 1963 in Tübingen ) was a German philosopher , educator and psychologist who is counted among the modern classics of education. He played a key role in establishing pedagogy as an independent academic discipline and influenced teacher training in Germany after the two world wars. He is also considered to be one of the most prominent representatives of humanities education and had a lasting impact on the educational discussion in the first half of the 20th century. Spranger received numerous honors for his scientific achievements. Spranger campaigned for the humanistic grammar school and coined the term third humanism . The goal of education is the inner formation of the human being.

Live and act

Imperial times

Origin and education

Spranger was born out of wedlock as the only son of the Berlin toy store owner Carl Franz Adalbert Spranger (1839–1922) and his later wife Henriette Bertha Schönenbeck (1847–1909), saleswoman in this shop. Spranger's parents married in 1884, Franz Spranger officially declared himself the biological father, and Eduard was allowed to use the family name Spranger .

From the age of six Spranger attended the Dorotheenstädtische Realgymnasium in Berlin. Due to outstanding achievements and the support of one of his teachers, he switched to the renowned grammar school “ Zum Grauen Kloster ” at the age of twelve and left it at Easter 1900 with a very good Abitur.

Spranger considered studying music, but decided to study philosophy as the main subject and psychology, pedagogy, history, economics, law, theology, German studies and music theory at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin . His teachers were Friedrich Paulsen , Wilhelm Dilthey , Erich Schmidt and Otto Hintze . A first attempt at a doctorate by the 19-year-old with Wilhelm Dilthey on the topic “The History of Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi ” proposed by him failed. With a thesis on the self-chosen topic “The epistemological and psychological foundations of historical science” Spranger received his doctorate in 1905 under Friedrich Paulsen and Carl Stumpf .

During this time Spranger met Catharina "Käthe" Hadlich and remained closely connected to her as a pen friend for life.

Higher daughter schools

After completing his doctorate , while looking for a post-doctoral thesis, Spranger became a temporary teacher at the private secondary school for girls “St. Georg ”in Berlin, which he left again in 1908. He began to work as a teacher at a private secondary school for girls with an attached teacher seminar run by Willy Böhm. In the same year his mother fell ill with tuberculosis , to which she succumbed after a year of suffering, during which Spranger cared for her devotedly and without regard for her own health. The death of his beloved mother, with whom he always had a particularly close relationship, shook Spranger deeply.

“For five years I gave a few hours of German lessons at what were then known as higher daughter schools. Growing up very lonely as the only child, I only got to know a figure of humanity who met the others in my own sisters at an early age. The eternally feminine in its most mature as well as its still naive form has supported me deeply inside, and although I lost my beloved mother at the time, I do not hesitate to say: this time at school was actually my happiest time. "

University professor

In 1909 Spranger completed his habilitation at Berlin University. His habilitation thesis was entitled Wilhelm von Humboldt and the Idea of Humanity . He held his inaugural lecture in 1909 and taught as a private lecturer at the University of Berlin until he was appointed to the University of Leipzig . There he received an extraordinary professorship for philosophy and education in 1911, which was followed by a full professorship in August 1912. Also in 1912 he was elected to the board of trustees of the Leipzig University for Women , where young women were trained to become kindergarten teachers , carers and nurses at an academic level; However, Spranger left the Board of Trustees in 1915 after heated arguments with the elderly director Henriette Goldschmidt about how the university was run. In solidarity exmatrikulierten seven of his students, whom he was now on private lessons. Spranger first met Anna Jenny Susanne Emilie Conrad in 1913 , whom he was to marry 21 years later.

Spranger was drafted as an untrained member of the Landsturm in 1914 after the outbreak of the First World War , but was never drafted. He felt torn inside, because he believed, like his peers, to have to do his duty with the weapon. At the same time, however, he was aware that he did not have the necessary psychological and physical qualifications for military service. The psychological stress and severe overwork meant that Spranger fell seriously ill in 1916 and had to take a year off from the university. He suffered from severe emaciation and pleurisy and was suspected of tuberculosis.

After his recovery Spranger was appointed advisor to the Prussian Ministry of Education in 1917. A year later he was elected to the board of the Society for German School and Educational History. In 1919 Spranger accepted an offer at the University of Berlin, having previously rejected calls at the Universities of Hamburg and Vienna . In 1922, Spranger's father died of stomach cancer at the age of 83 . The father-son relationship was tense throughout life. A year later Spranger was appointed dean of the Faculty of Philosophy and Natural Sciences at the University of Berlin. In what was now the most glamorous period that followed, Spranger published his two main works, Lebensformen (1921) and Psychology of Adolescence (1924), in quick succession . He gained considerable influence on Prussian and German school policy, especially with regard to teacher training. Between 1925 and 1943, the journal Die Erziehungs co-founded by him in 1925 determined the pedagogical discussion in Germany: Spranger wanted to limit higher teacher training at the university to pedagogical philosophy and specialist training, but to allow practical school pedagogy and empirical-experimental parts to take place at other institutions because, according to his vision, the university should be a place for scholarly training in personal contact and not a mass enterprise. In 1925 he was accepted into the Prussian Academy of Sciences . Spranger gave his very popular lectures to up to 1,300 students (1929) for a total of about 14,000 enrolled students. As a sought-after and respected speaker on public occasions, he spoke about welfare ethics and victim ethics at the establishment of the Reich at Berlin University in 1930, and in 1932 at the request of Chancellor Brüning on the radio about German hardship, German hope. In 1934 Eduard Spranger married Susanne Conrad after having been acquainted for over twenty years in Berlin.

Spranger and the women

Spranger thought in terms of gender polarities. In his opinion, women stand for feeling, for a holistic feeling, for life. It is a healing addition to the man. The cultural responsibility of women is different from that of men. Contemporary women valued Spranger for the fact that he did not reduce them to family work, but instead gave them selected cultural areas as a field of activity. At the turn of the year 1915/1916 Spranger had written a brochure entitled “The idea of a university for women and the women's movement”, which was enthusiastically received by Gertrud Bäumer , among others . The font is a sign of Spranger's intense engagement with the topic of women's studies, which he initially disapproved of. In 1908 he wrote to Käthe Hadlich:

“Dear friend, studying women is a lot of nonsense; they all do nothing. "

A few years later, he was impressed by the intellectual achievements of individual women, while at the same time he complained irritably about the lack of seriousness on the part of his female and male students. His now disparate attitude towards women’s studies was further shown in letters to Käthe Hadlich, in which he wrote that his colleges were only called “Knitting School” internally and that it was

"[...] a misery that the women have now all got the study fever."

Nevertheless, he felt called to lead women up to their higher, "true selves". The background was an idea that he had adopted from his role model Wilhelm von Humboldt : the model of an ideal complement to the sexes. Spranger's most important advisors were always women, first his mother, later especially his wife Susanne Conrad and Käthe Hadlich. Spranger had found a confidante in Käthe Hadlich over a period of 60 years who, with her understanding and reactions, gave essential stimuli to his striving for male self-realization as a scholar. A doctoral student and a devoted student of Spranger was the pedagogue Mathilde Mayer .

time of the nationalsocialism

Steel helmet

Having grown up in the national-conservative tradition of the Prussian virtues , Spranger met the Weimar Republic with skepticism. Spranger was politically close to the German National People's Party , whose armed arm, the Stahlhelm , he joined in 1933. He took part in meetings of the university group of the Stahlhelm as well as in roll calls in uniform and was intended for a "cultural management function". From 1933 he also took part regularly in events organized by the German Society for Defense Policy and Science .

As one of several board members of the Association of German Universities, Eduard Spranger drafted and signed the so-called "Würzburg Declaration" on April 22nd, 1933, which was supposed to formulate the quasi-official attitude of the universities to National Socialism. In an ambivalent way, this declaration was generally positive about the National Socialist revolution of the state and the politicization of the university. On the other hand, however, such a politicization of the university was rejected, which meant a "narrowing down to special views" and the "self-administration by the rector, senate and faculties" and the "self-completion of the teaching staff" were expressly defended.

“The rebirth of the German people and the rise of the new German Empire mean for the universities of our fatherland the fulfillment of their longing and the confirmation of their ever-fervent hopes. [...] After the unfortunate class contradictions have ceased , the hour has come again for the universities to develop their spirit from the deep unity of the German people's soul and to consciously direct the multifarious struggle of this soul, suppressed by hardship and foreign dictation , to the tasks of the present. ] Out of the inner forces of our ties to the people, for the sake of our people and empire we will take up the fight not only against oppression from outside, but also against damage to the people through lies, conscience pressure and unspirituality. "

The last sentence of this declaration was understood by the regime as an attack. Thereupon the association management moved away from Spranger and declared the declaration to be a private expression of Spranger's opinion.

In March of the same year Spranger declared, referring to a Platonic form of pedagogy, that the "positive core of the National Socialist movement" was to be seen in the emphasis on the "sense for the nobility of blood and for common blood" and "down-to-earth loyalty to one's home "As well as the" care for a physically and morally high quality offspring "is required. At the end of 1932 Spranger had expressed himself critically about National Socialism in letters to his friend Käthe Hadlich: “[...] It is now high time, my dear, that you gave the National Socialists valet. They have not only gotten stuck, but have become a society that is dangerous to the state. It's a shame about the originally pure wanting. But it just doesn't work without intelligence. "

Resignation petition 1933

At the university, Spranger turned against actions by the National Socialist Berlin student body in 1933. In particular, he protested against an anti-Semitic, inflammatory poster of the NS student union , the “12 theses against the un-German spirit” and against the “espionage decree”, in which students were asked to use denunciations to help bring the “law to restore the professional civil service” into reality. This appeared to him, as he later wrote, as "a degradation of the scientific spirit for which the university has to stand up". Shortly afterwards, when a new chair and an institute for political education next to the Spranger chair were set up for the Nazi educator Alfred Baeumler , without Spranger being informed, Spranger perceived these two measures as an “offense in office” and as the beginning of one "Stenciled (alias politicized) university". Because Spranger claimed for himself that he had devoted considerable academic attention to the “connection between state and education” in his writings and lectures and he was convinced that he had advocated a “German attitude, that is, for the national in the sense of a healthy nationalism” , he came to the conclusion that the responsible Minister Rust had not taken notice of his efforts at all. For him a "limit" had been reached and on April 25, 1933 he spontaneously submitted a resignation. The above-mentioned undisciplined actions of the National Socialist students directed against the authority of the professors as well as his "inner impossibility to submit to this censorship" were the main motive according to him. Spranger's resignation was commented on in many domestic and foreign newspapers. The ministry was considering his dismissal under Section 4 of the Restoration of Civil Service Act , which would have resulted in the loss of his pension. After the intervention by Vice Chancellor von Papen , Spranger was initially only given leave of absence on May 17. Spranger withdrew the resignation on the advice of his friends in a conversation with Minister Rust on June 9th, after he had already resumed his official business.

He kept his chair as well as the management of the educational seminar next to the Baeumler Institute, undisturbed by the National Socialists, without ever having joined the NSDAP , and lectured until 1945. Between 1933 and 1934 Spranger negotiated unsuccessfully for a professorship in Zurich. Later he wrote about this period: “My influence in the university and faculty was of course at an end; I myself also withdrew from business that went beyond my teaching activities for the duration of the entire epoch ”. "[..] I was able to continue my teaching activity, although I had to permanently switch off some of my main areas". The episode seems to have intimidated Spranger. On June 18, 1933, with a covert reference to the Dachau concentration camp , he asked : "Who knows whether you might not be detained in a recently popular resort near Munich!" In April 1938 Spranger, now chairman of the Berlin branch of the Goethe Society , initiated the exclusion of Jewish members of the local group.

Of the 605 lectures that Spranger gave throughout his life, 211 relate to the Nazi era .

In a then unpublished lecture in front of the Stahlhelm (October 21, 1933), Spranger developed a five-point program of constructive criticism of National Socialism. He criticized the disregard for religion, person, legal thought, folk thought, and science. In summary, he warned of the "danger of a Caesar cult". In a similar way in 1935 in a lecture entitled “Is there a liberal science?” To the Wednesday Society , he differentiated his understanding of science from that of National Socialism by emphasizing the orientation towards the “will to truth” instead of the “will to power”.

Japan

In 1936, the Spranger couple visited Japan , where Spranger was almost the first German exchange professor to give lectures. Spranger had taken over the scientific management of the Japanese-German Cultural Institute there for one year on behalf of the German government. After his return to the University of Berlin in 1939 he was drafted into the army psychological service in the Reichswehr , in connection with which he held psychological exams for airmen. Benjamin Ortmeyer is critical of Spranger's attitude during the Nazi era:

“The summary of his politically reactionary positions before 1933 in the anthology“ People, State, Education ”shows the theoretical difficulties of distinguishing“ German ideology ”from Nazi ideology. […] Spranger's political options before and after 1933 include approval of the alliance of the NSDAP with the German Nationalists, Hitler and Hindenburg, whereby Spranger's accentuation within the framework of this alliance and within the framework of supporting the “great positive core” of the National Socialist movement on the line Hindenburgs lay. With or without conviction: Spranger supported [...] terminologically the National Socialism [...] "

Wednesday company

Eduard Spranger always defended the freedom of science and opposed the leadership claim of politics: “Work on science can be placed more at the service of the state and national education; but the truth cannot be politicized. There are still many ambiguities and misunderstandings about these things. ”Due to the negative experiences with the increasing radicalization of the National Socialist dictatorship and as a member of the Berlin Wednesday Society since 1934, Spranger changed“ late, but with insight ”into a convinced democrat. A case from 1941 is documented that Spranger wanted to intervene to help against the deportation of Jews. He was also one of the founders and editors of the journal Die Erbildung , which appeared from 1925 to 1943, and together with the publishing house in 1943 refused to merge it with the journals National Socialist Education and Weltanschauung and Schule . Thereupon the education was stopped, officially for reasons necessary for the war. After the assassination attempt on Hitler, Spranger was imprisoned as a co-suspect in the Moabit remand prison in Berlin. Both his membership of the Wednesday Society and a statement by Ludwig Beck that Spranger agreed with him in the assessment of the current government were bothersome. However, Beck had not informed Spranger of the impending coup attempt. At the intervention of the Japanese ambassador, Spranger was released from custody after ten weeks. Spranger claimed "that the legal counsel of the University [Berlin] should be instructed to spread that there was no shadow of suspicion left on me," and he threatened to appeal against an alleged order that his journalistic possibilities would be restricted should.

Post-war years

After the Second World War , Spranger became the first post-war rector to temporarily head the Humboldt University in Berlin for a short time . This task was offered to him at the end of May 1945 by the last prorector of the Berlin University Grapow and by the new city councilor for popular education at the magistrate for Greater Berlin, Otto Winzer . On May 20, 1945, fourteen professors and lecturers met for the first time. Spranger tackled the central tasks with them: finding a replacement for the destroyed university premises, drawing up a budget, and a provisional curriculum. In addition, questionnaires for teachers and students to find those who were at least not actively involved in National Socialist organizations, as the Allies demanded in their denazification regulations. Spranger assumed that the university in the Soviet- occupied part of Berlin was of course under four-power administration . However, this was questioned by the Russian side from September 1945 at the latest, which wanted sole control over the university. On July 20, 1945, he was first placed under house arrest by the United States military authorities and then detained for a week and interrogated by an American professor: “I was detained in a barbed wire compound in Wannsee for seven days. There I met the last rector of the university, the famous orthopedic surgeon Kreuz , and it was otherwise a very enjoyable time. ”The reason for the arrest was possibly the cars with Soviet license plates that were often parked in front of his house because of Spranger's organizational work Military authorities were suspicious. Nor did the Americans seem to have known about his role as acting rector . The Americans confiscated his house in Berlin-Dahlem for their own purposes, but he and his wife were still allowed to live in a room in the basement of the house. On the one hand Spranger did not succeed in establishing a productive relationship with the western occupation authorities, which he later even accused of indifference, on the other hand he came to the administration because of his attempts to find buildings for the university in the western part of Berlin and the question of submitting precise curricula , in conflict with the Russian side. He later wrote: “There was no other way of preserving something of the well-founded, genuine essence of the German university than the effort to bring it under four-power control.” “At that time I found neither the American nor the English Occupation positions understanding and support. "

In October 1945 Spranger was removed from his position as rector, but remained a professor at Berlin University until 1946. He received offers at the universities of Göttingen , Hamburg , Cologne , Munich and Tübingen and at the Mainz University of Education . He could not accept the call to the University of Hamburg because he was not allowed to move. Finally, he accepted the call, supported by Theodor Heuss , at the University of Tübingen, where he was appointed full professor of philosophy in 1946. In 1950 Spranger officially retired , but held lectures and seminars until 1958. In 1951 Spranger was allowed to deliver the speech on the second anniversary of the Federal Republic of Germany in the house of the German Bundestag:

“Nobody should be ashamed of honest relearning. Everything in the world has changed. Should we not need transformation alone? -. Die and become! When I look back on my life, I have had to dismiss a lot of things that were close to my heart in not easy self-conquest. 'The dearest is scolded away from the heart'. "

In 1960 the lifelong friend Käthe Hadlich died and in 1963 his wife Susanne. Spranger also died only about five months later. He was buried next to his wife in the Tübingen city cemetery. A year after his death, a comprehensive reminiscence appeared in which well-known personalities such as Otto Friedrich Bollnow , Andreas Flitner , Kurt Georg Kiesinger and Theodor Heuss paid tribute to Spranger's life and work.

Psychology and Philosophy of Education

The goal of education

Spranger stood in the tradition of hermeneutics of his teacher Wilhelm Dilthey and took Pestalozzi's and Goethe's ways of thinking as models. For Spranger, education was the uniform, structured, developable form of the individual acquired through cultural influences , which enables them to achieve objectively valuable cultural achievements and makes them capable of experiencing and understanding cultural values. He recognized the indispensable goal of education in the inner formation of the human being, in which the diversity of interests and the strength of character of morality are combined and who should thus find a consistent harmony with himself. The human individuality must be “purified” “from a naturally born disposition to an artistic spiritual constitution” , which must not be exhausted either in mere knowledge or in mere ability to do certain work or in mere warmth of feeling. The educational ideal is "[...] the vivid imagination of a person in whom the general human characteristics are realized in such a way that not only the normal, but also the teleologically valuable of the same is expressed in the highest conceivable form."

The truth of superficial knowledge is to be distinguished from the "center truth" of the closest relationships, according to which that circle of knowledge is determined through which the person is blessed in his situation . Not just abstract contexts of knowledge, but only the reference to the individual situation , to the near and distant real connections , causes knowledge to be formed. For Spranger, the principle of education in the organically concentric circles of life was synonymous with the home principle . In this way the individual world emerges as a concentric system of circles of life: family, job, nation and state. The focus is on God as love. For Spranger, religion was the highest value experience. Its content is the totality of values, namely God. Man owes him what neither science nor philosophy can offer: the total sense of the world.

Humanistic position

Spranger dedicated the 1921 lecture “The current state of the humanities and schools” to his friend Werner Jaeger . Both advocate ancient languages and a philosophy of education . Jaeger visited Spranger in Tübingen after the war and exchanged letters with him. Spranger coined the term Third Humanism . Philology leads man down into those depths of his inner being, where his limited existence finds redemption in a total sense. According to Spranger, humanism is " the historically in-depth research on the problem of what man is in the total structure of his powers, the question of his possibilities, his realities and the peaks he has ever reached." The past should be represented in the intellectual history in such a way that it can be understood can and have a meaningful effect on the present. Spirit is to be understood as the totality of human community and its determinations. Spiritual phenomena would result from the interweaving of the subjective mind with the objective mind.

Life forms

Spranger's cultural pedagogy combines general with practical vocational training and is determined by the category of spiritual awakening . Eduard Spranger's most important work was published in 1921 with the title Lebensformen . It was not only important for psychology, but also for the humanities and cultural philosophy. In addition to the psychic and the physical as the known realms of being, there is, according to Spranger, a more original, different ontic reality. Its peculiar functional laws are the spiritual or the spiritual life. Therefore, psychology should not be satisfied with the meaningless and neutral mental functions, which include feeling, desire and remembering. Rather, it should devote itself to the analysis of the meaningful structures of mental life. The soul must be seen as embedded in the great structures of the spiritual life. These are subject to their own laws and extend beyond what is only naturally conditioned. They are not only of a spiritual nature. Particular attention should be paid to the area where the objective cultural world and the subject meet and permeate. The structural laws of culture are to be worked out. Spranger called the mind fixed in the structures and subject areas of culture the objectified mind . He described the supra-individual group spirit that manifests itself in the organizational forms of society as objective spirit . He named the normative, supra-individual orders of law and morality as the normative spirit . The thinking and acting of the individual can only be understood from this overall context. Spranger constructed the so-called ideal types of individuality as a mere aid to knowledge, but not as true images of reality . These include the religious, the aesthetic, the social, the political, the theoretical and the economic person.

Psychology of Adolescence

In his work Psychologie des Jugendalters , published in 1924 , Spranger explained how young people gain a share in the meaning of the various cultural areas. Only that which is classified as a constituent element in a whole of values makes sense:

“Accordingly, it makes sense to have an order or a connection of members that form a whole of value, are related to a whole of value or help bring about a whole of value. The parts that can be distinguished in a whole only make sense if 1. this whole can be put under a value point of view, 2. the connection of the parts to the whole is determined by this value point of view, i.e. if they also make the value possible and are regarded as essential, orderly, not freely replaceable parts. [...] But whether life as a whole (e.g. an individual human life) has meaning depends on whether this human life can be thought of as a part of some larger value context. "

The soul of man grows gradually into the objective and normative spirit of the respective time. When considering them, Spranger also took a holistic approach:

“[One must] see the so-called soul itself as a life structure that is aimed at value realization. We call such an entity in the broadest sense a structure. A structure of reality has an articulated building or structure if it is a whole, in which each part and each partial function performs an achievement that is significant for the whole, namely in such a way that the construction and achievement of each part is conditioned by the whole and consequently only by the All in all understandable. [...] Just as in the physical organism every organ is conditioned by the form of the whole and the whole lives only through the interaction of all partial services, so the soul is also a teleological context in which each individual side can be understood solely from the whole Unity of the whole is based on the structured partial services and individual functions. "

In particular, the training of young sports teachers found a special hold in Spranger's psychology of adolescence , as he gave physical education a special value, but moved this closer to training as an officer . After the World War, there was a lively correspondence with Carl Diem , who was looking for a suitable philosophical underbelly for the young German Sport University in Cologne .

This work served - together with the Lebensformen - many generations of teachers, parents and young people as an orientation for education and established Spranger's reputation as a humanistic interpreter of the spiritual world.

Love and vitality

According to Spranger, upbringing always involves mutual psychological interpretation and understanding. In Spranger, the individual becomes “an object of love as a vessel of values.” In a relationship of love, mutual understanding should develop. On this basis, the love for the inner creation of cultural goods can then be awakened and the person can become "sculptural":

“[…] The relevant act that he wants to create must be alive in the educator, and he must finally bring it to such an isolated representation that it comes out pure in the replica and is felt with relish in its specific meaning. We call this adding value, that is, directing the feeling towards basic spiritual acts through which the ego becomes aware of its strength and its constructive work. "

Vocational and general education

Spranger is one of the classics of professional education and has made significant contributions to its theory. In particular, as a representative of Wilhelm von Humboldt's position, he dealt with the question of the relationship between general and vocational education . In place of the idea of a uniform general education, Spranger adopted the concept of a school structure differentiated according to career paths. His “three-step theory” falls into this area, according to which a person first acquires a basic education in the so-called general school system. On the second level, he then specializes these in relation to his own interests and talents. Here one could already speak of vocational training. On the third level, the person then strives from the set or found educational center again into the distance:

“He now follows the rays emanating from his central area and takes control of all of life on these lines, as far as we can speak of them in humans. In this way he gradually arrives at a kind of general education that contains more than the training of basic forces and the intellectual outlines of a worldview. It extends more and more to the content of the cultural goods and thus fills the subject with a cultural content that corresponds to the time and enables participation in cultural life according to the individual educational capacity. "

The respective phase can begin before the previous one is completed.

Memberships and honors

Memberships

Spranger had been a member since 1934 and, after 1945, partly the initiator of the reactivated Berlin Wednesday Society , the Goethe Society Weimar, since 1941 a member of Meineckes Dahlemer Society, a member of the German Research Foundation , from 1951 to 1954 also its Vice President, and the German Society for Psychology . He was a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences and its successor, the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin , honorary member of the German Academy for Language and Poetry , Darmstadt, corresponding member of the Saxon Academy of Sciences in Leipzig, the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and the Austrian Academy of Sciences , Vienna. In 1962 he became an honorary member of the Association for Patriotic Natural History in Württemberg . From 1959 to 1963 he was a member of the Advisory Board of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation .

Awards

In the course of his life Spranger received a large number of high civil merit orders and awards, including the Imperial Japanese Order of the Sacred Treasure 2nd Class, the Greek Order of the Redeemer and the Great Federal Cross of Merit with Star and Shoulder Ribbon . He was knighted in 1952 as a knight of the order Pour le Mérite (peace class) - one of the highest honors that can be bestowed on a scientist or artist. He received the constitutional medal in gold of the state of Baden-Württemberg, presented by Kurt Georg Kiesinger , the golden medal of the city of Tübingen and the golden medal of the Goethe Society , presented by Max Planck .

Honorary doctorates

Spranger was awarded honorary doctorates from the Universities of Athens , FU Berlin (1952), Budapest , Cologne , Padua , Tokyo and the Mannheim University of Applied Sciences .

Naming and renaming

In West Germany the post-war period he enjoyed such a good reputation that eight schools were named in the former Federal Republic of Eduard Spranger.

From around 2010 these honors were increasingly critically questioned because of Eduard Spranger's role in the Nazi era . For Benjamin Ortmeyer , Spranger from the National Socialist Education Research Center at the Goethe University in Frankfurt is one of the educational “gray area collaborators” and should not be honored by school names. As a conservative nationalist who welcomed large parts of the National Socialist ideology and attracted attention with anti-Semitic convictions, many critics of the use of the name believe that he was involved in making the Nazis acceptable in bourgeois circles. In Frankfurt am Main , this debate led to an initial consequence in the summer of 2017 when the former Eduard Spranger School in Frankfurt-Sossenheim decided to rename itself the Edith Stein School at the start of the 2018 school year . In Mannheim , a special school in the north of the city previously named after Spranger took on the new name Gretje-Ahlrichs-Schule . In Filderstadt, the local council decided unanimously in April 2019 to follow the proposal of the school community to rename the school after Elisabeth Selbert . This not only honored one of the mothers of the Basic Law , but cleverly also received the initials of the ESG. In Gelsenkirchen , the previous Eduard-Spranger-Berufskolleg, a business high school in Gelsenkirchen-Buer , changed its name to Berufskolleg am Goldberg with effect from the beginning of the 2019/20 school year . For similar reasons, the renaming of the Eduard-Spranger-Gymnasium in Landau in the Palatinate has been discussed since 2017 , but met with disinterest among the students and was rejected by a majority of school and teacher representatives in May 2018.

Fonts (selection)

- The basics of history. An epistemological and psychological investigation. Reuther & Reichard, Berlin 1905.

- Wilhelm von Humboldt and the idea of humanity. Reuther & Reichard, Berlin 1909.

- Life forms. A blueprint. In: Festschrift for Alois Riehl. Offered by friends and students on his 70th birthday. Niemeyer, Halle (Saale) 1914, pp. 416–522 (also reprint. Later: Lebensformen. Spiritual psychology and ethics of personality. 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Niemeyer, Halle (Saale) 1921).

- The idea of a college for women and the women's movement. Dürr, Leipzig 1916.

- Culture and education. Collected educational essays. Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1919.

- Psychology of Adolescence. Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1924.

- About the endangerment and renewal of the German university. In: Education. Vol. 5, 1929/1930, pp. 513-526. (Also special print)

- with Michael Doeberl , Otto Scheel , Wilhelm Schlink , Hans Sperl , Hans Bitter and Paul Frank (eds.): Das Akademische Deutschland . 4 volumes, 1 register volume by Alfred Bienengräber. CA Weller Verlag, Berlin 1931.

- People, state, education. Collected speeches and essays. Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1932.

- Goethe's Weltanschauung (= Insel-Bücherei. Vol. 446). Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1933.

- From Friedrich Froebel's world of thoughts (= treatises of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class. Born 1939, No. 7, ZDB -ID 210015-0 ). de Gruyter et al., Berlin 1939.

- Schiller's mindset. Reflected in his philosophical writings and poems (= treatises of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class. Born 1941, No. 13). de Gruyter et al., Berlin 1941.

- The philosopher von Sanssouci (= treatises of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. Philosophical-Historical Class. Born 1942, No. 5). Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1942 (2nd, expanded edition. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1962).

- Goethe's worldview. Speeches and essays. Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1943.

- The magic of the soul. Religious and philosophical preludes. Evangelische Verlags Anstalt, Berlin 1947.

- Pestalozzi's ways of thinking. Hirzel, Stuttgart 1947.

- On the history of the German elementary school. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1949.

- Pedagogical Perspectives. Contributions to current educational issues. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1951.

- Foreword. In: Günther Just †: Four lectures. Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1951, pp. 5-7.

- Cultural issues of the present. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1953.

- Thoughts on shaping existence. From lectures, papers and writings. Selected by Hans Walter Bähr. Piper, Munich 1954.

- My conflict with the Hitler government in 1933. Printed as a manuscript in March 1955. Laupp, Tübingen 1955 (already written in 1945).

- The born educator. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1958.

- The Law of Unwanted Side Effects in Education. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1962.

- Human life and human issues. Collected radio speeches (= Das Heidelberger Studio. Vol. 30, ZDB -ID 382678-8 ). Piper, Munich 1963.

literature

- Kurt Aurin: Spranger, Eduard , in: Baden-Württembergische Biographien . Volume 4. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-17-019951-4 , pp. 351–354 ( online )

- Hans Walter Bähr, Theodor Litt , Nikolaus Louvaris , Hans Wenke (eds.): Education for humanity. Education in the upheaval of times. Festschrift for Eduard Spranger on his 75th birthday, June 27, 1957. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1957.

- Hans Walter Bähr, Hans Wenke (Ed.): Eduard Spranger. His work and his life. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1964.

- Rüdiger vom Bruch , Christoph Jahr (ed.): The Berlin University in the Nazi era. Volume 2: Departments and Faculties. Steiner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-515-08658-7 .

- Peter Drewek: Eduard Spranger (1882–1963). In: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (ed.): Classics of Pedagogy. Volume 2: From John Dewey to Paulo Freire (= Beck series. 1522). CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49441-2 , pp. 137-151.

- Walter Eisermann, Hermann J. Meyer, Hermann Röhrs (Ed.): Measure. Perspectives on thought by Eduard Spranger. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1983, ISBN 3-590-14256-1 .

- Michael Fontana: "... that pedagogical thrust into the heart." Educational and biographical-political continuities and discontinuities in the life and work of Eduard Spranger (= European university publications. Series 11: Pedagogy. Vol. 993). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2010, ISBN 978-3-631-59021-8 .

- Ulrich Herrmann : Spranger, Eduard. In: Walter Killy (Ed.): Literaturlexikon. Authors and works of German language. Volume 11: Sem - Var. Bertelsmann-Lexikon-Verlag, Gütersloh et al. 1989, ISBN 3-570-04681-8 , pp. 118-119.

- Dieter Hoffmann: Spranger, Eduard . In: Who was who in the GDR? 5th edition. Volume 2. Ch. Links, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86153-561-4 .

- Joachim S. Hohmann (Ed.): Contributions to the philosophy of Eduard Spranger (= Philosophical writings. Vol. 17). Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-428-08540-X .

- Leonhard Jost et al. (Ed.): Eduard Spranger. On the philosophy of education and educational practice (= Schweizerische Lehrerzeitung. Taschenbuch. Vol. 7, ZDB -ID 796346-4 ). Verlag Schweizerischer Lehrerverein, Zurich 1983.

- Rita Klussmann: The idea of the educator in Eduard Spranger against the background of his educational and cultural conception (= European university publications. Series 11: Pedagogy. Vol. 217). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-5582-5 (also: Munich, University, dissertation, 1983).

- Roland Kollmann : Education - Educational ideal - Weltanschauung. Studies on the educational theory of Eduard Spranger and Max Fresisen-Koehler . Henn, Kastellaun et al. 1972 (at the same time: Münster, Universität, Dissertation, 1972).

- Gerhard Meyer-Willner (Ed.): Eduard Spranger. Aspects of his work from today's perspective. With a previously unpublished autobiographical sketch by Eduard Spranger. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2001, ISBN 3-7815-1163-4 .

- Benjamin Ortmeyer : Myth and Pathos instead of Logos and Ethos. On the publications of leading educationalists during the Nazi era: Eduard Spranger, Herman Nohl, Erich Less and Peter Petersen. Beltz, Weinheim et al. 2009, ISBN 978-3-407-85798-9 (also: Frankfurt am Main, University, habilitation paper, 2008).

- Benjamin Ortmeyer (ed.): Eduard Spranger's writings and articles in the Nazi era. Documents 1933–1945 (= documentation ad fontes. Vol. 1, ZDB -ID 2449560-8 ). University of Frankfurt, Faculty of Education, Frankfurt am Main 2008.

- F. Hartmut Paffrath: Eduard Spranger and the elementary school. A historical-systematic investigation. With an appendix of unpublished writings by Eduard Spranger. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 1971, ISBN 3-7815-0130-2 .

- Karin Priem: Education in Dialog. Eduard Spranger's correspondence with women and his profile as a scientist (1903–1924) (= contributions to historical educational research. Vol. 24). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2000, ISBN 3-412-06999-X (also: Tübingen, University, habilitation paper, 1998).

- Joachim Ritter among others (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Completely revised edition of Rudolf Eisler's Dictionary of Philosophical Terms. Schwabe, Basel 1971–2007, ISBN 3-7965-0115-X .

- Werner Sacher: Eduard Spranger 1902–1933. An educational philosopher between Dilthey and the Neo-Kantians (= European university publications. Series 11: Pedagogy. Vol. 347). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1988, ISBN 3-8204-1284-0 (also: Bamberg, University, habilitation paper, 1987).

- Werner Sacher, Alban Schraut (ed.): People's educator in poor time. Studies on the life and work of Eduard Spranger (= educational concepts and practice. Vol. 59). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2004, ISBN 3-631-52586-9 .

- Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2007, ISBN 978-3-7815-1504-8 (also: Erlangen-Nürnberg, University, dissertation, 2006).

- Alban Schraut, Werner Sacher: Spranger, Franz Ernst Eduard. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , pp. 743-745 ( digitized version ).

- Sun-Jae Song: The concept of awakening in Eduard Spranger's pedagogy. Tübingen 1991 (Tübingen, University, dissertation, 1991).

- Ute Waschulewski: The value psychology of Eduard Spranger. An investigation into the topicality of the "forms of life" (= texts on social psychology. Vol. 8). Waxmann, Münster et al. 2002, ISBN 3-8309-1131-9 (also: Hamburg, University, dissertation, 2001).

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-32264-6 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Eduard Spranger in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Eduard Spranger in the German Digital Library

- Overview of Eduard Spranger's courses at the University of Leipzig (summer semester 1912 to summer semester 1914)

- Eduard Spranger Society

- Eduard Spranger in the professorial catalog of the University of Leipzig

- Newspaper article about Eduard Spranger in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Digital edition: Correspondence (1903-1960) between Eduard Spranger and Käthe Hadlich

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, p. 352.

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, pp. 139, 352.

- ^ Eduard Spranger: Brief Self-Representations I (1961). In: Hans Walter Bähr, Hans Wenke : Eduard Spranger. His work and his life. 1964, pp. 13-21.

- ↑ Spranger in a biographical review from 1953, Karin Priem: Bildung im Dialog. 2000, p. 71 f.

- ↑ Karin Wittneben and Maria Mischo-Kelling: Nursing education and nursing theories , Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich, Vienna, Baltimore 1995, pp. 259 + 260.

- ↑ Christine Auer: History of the nursing professions as a subject: the curriculum development in nursing education and training , dissertation Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg , academic supervisor Wolfgang U. Eckart , self-published Heidelberg 2008, p. 146–150.

- ↑ Sylvia Martinsen, Werner Sacher (Ed.): Eduard Spranger and Käthe Hadlich. A selection from the letters from 1903 to 1960. Julius Klinkhardt Verlag, Bad Heilbrunn 2002, ISBN 3-7815-1116-2 , p. 392; Gerhard Meyer-Willner: Eduard Spranger and teacher training. Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 1986, ISBN 3-7815-0592-8 , pp. 91-94.

- ^ Michael Grüttner : The student body in democracy and dictatorship. In: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (Hrsg.): History of the University under the Linden 1810-2010. Volume 2. The Berlin University between the World Wars 1918-1945. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-004667-9 , p. 188.

- ↑ Sylvia Martinsen, Werner Sacher (Ed.): Eduard Spranger and Käthe Hadlich. A selection from the letters from 1903 to 1960. Julius Klinkhardt Verlag, Bad Heilbrunn 2002, ISBN 3-7815-1116-2 , p. 392; University professor Dr. Eduard Spranger: Speech given on January 25, 1932. In: Uwe Henning, Achim Leschinsky (Ed.): Disappointment and contradiction. Deutscher Studien Verlag, Weinheim 1991, ISBN 3-89271-247-6 , S: 77-82

- ↑ Annelise Fechner-Mahn: Cultural responsibility of women with Eduard Spranger then and now. In: Gerhard Meyer-Willner (Ed.): Eduard Spranger. Aspects of his work from today's perspective. 2001, pp. 110-120, here p. 112 f.

- ^ Eduard Spranger to Käthe Hadlich 1908, Karin Priem: Education in dialogue. 2000, p. 97.

- ^ Eduard Spranger to Käthe Hadlich 1915, Karin Priem: Education in dialogue. 2000, p. 138.

- ↑ Annelise Fechner-Mahn: Cultural responsibility of women with Eduard Spranger then and now. In: Gerhard Meyer-Willner (Ed.): Eduard Spranger. Aspects of his work from today's perspective. 2001, pp. 110-120, here p. 116 f.

- ↑ See Spranger: The Philosopher von Sanssouci. 1942.

- ^ Klaus Himmelstein: Eduard Spranger in National Socialism. In: Werner Sacher, Alban Schraut (ed.): People's educators in poor time. 2004, pp. 105-120.

- ↑ Sylvia Martinsen, Werner Sacher (Ed.): Eduard Spranger and Käthe Hadlich. A selection from the letters from 1903–1960. Verlag Julius Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 2002, ISBN 3-7815-1116-2 , pp. 300, 303.

- ^ Klaus Himmelstein: Eduard Spranger in National Socialism. In: Werner Sacher, Alban Schraut (ed.): People's educators in poor time. 2004, pp. 105–120, here 112.

- ↑ Christoph Jahr: The National Socialist Takeover and Its Consequences. In: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (Hrsg.): History of the University under the Linden 1810-2010. Volume 2. The Berlin University between the World Wars 1918-1945. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-004667-9 , pp. 312-313.

- ↑ Quoted from Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Deutsche Gesellschaftgeschichte. Volume 4. 2003, p. 823; Eduard Spranger: My conflict with the Hitler government in 1933 (printed as a manuscript in March 1955, but written in 1945). In: Léon Poliakov , Joseph Wulf : The Third Reich and its thinkers. Fourier, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-925037-46-2 , pp. 89-94, here p. 91.

- ↑ Christoph Jahr: The National Socialist Takeover and Its Consequences. In: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (Hrsg.): History of the University under the Linden 1810-2010. Volume 2. The Berlin University between the World Wars 1918-1945. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-004667-9 , p. 313.

- ↑ Spranger: March 1933. In: Education. Vol. 8, No. 7, 1932/1933 (April 1933), pp. 401-408, here p. 403.

- ↑ Sylvia Martinsen, Werner Sacher (Ed.): Eduard Spranger and Käthe Hadlich. A selection from the letters from 1903 - 1960. Julius Klinkhardt Verlag, Bad Heilbrunn 2002, ISBN 3-7815-1116-2 , p. 285; Alban Schraut: Biographical studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, p. 289 f.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Horn : Educational sciences at the Berlin Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in the time of National Socialism. In: Rüdiger vom Bruch, Christoph Jahr (ed.): The Berlin University in the Nazi era. Volume 2: Departments and Faculties. 2005, pp. 215–228, here p. 219., Heinz-Elmar Tenorth: Eduard Spranger's university-political conflict 1933. Political action of a Prussian scholar. In: Journal for Pedagogy. Vol. 36, No. 4, 1990, ISSN 0044-3247 , pp. 573-596.

- ^ Eduard Spranger: My conflict with the Hitler government in 1933 (printed as a manuscript in March 1955, but written in 1945). In: Léon Poliakov , Joseph Wulf : The Third Reich and its thinkers. Fourier, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-925037-46-2 , pp. 89-94, here p. 91.

- ^ Heinz-Elmar Tenorth: Eduard Spranger's university-political conflict 1933. Political action by a Prussian scholar. In: Journal for Pedagogy. Vol. 36, No. 4, 1990, ISSN 0044-3247 , pp. 573-596, here pp. 575, 592.

- ^ Eduard Spranger: Spranger's memorandum for three days (typewritten copy). In: Uwe Henning, Achim Leschinsky (Ed.): Disappointment and contradiction. Deutscher Studien Verlag, Weinheim 1991, ISBN 3-89271-247-6 , S: 127-131, here p. 128 .; Eduard Spranger: My conflict with the Hitler government in 1933 (printed as a manuscript in March 1955, but written in 1945). In: Léon Poliakov, Joseph Wulf: The Third Reich and its thinkers. Fourier, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-925037-46-2 , pp. 89-94, here pp. 91-94.

- ↑ Uwe Henning, Achim Leschinsky: Support, Adaptation, Protest, Resistance. Analysis of contemporary press reactions to Eduard Spranger's resignation from the early summer of 1933. In: Uwe Henning, Achim Leschinsky (Ed.): Disappointment and contradiction. Eduard Spranger's Conservative Position in National Socialism. , Deutscher Studien Verlag, Weinheim 1991, ISBN 3-89271-247-6 , pp. 3-48.

- ^ Heinz-Elmar Tenorth: Eduard Spranger's university-political conflict 1933. Political action by a Prussian scholar. In: Journal for Pedagogy. Vol. 36, No. 4, 1990, ISSN 0044-3247 , pp. 573-596, here pp. 575, 579.

- ^ Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Berlin: Personnel and course directory. ZDB -ID 2391685-0 , online.

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, pp. 297-298.

- ^ Eduard Spranger: My conflict with the Hitler government in 1933 (printed as a manuscript in March 1955, but written in 1945). In: Léon Poliakov, Joseph Wulf: The Third Reich and its thinkers. Fourier, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-925037-46-2 , pp. 89-94, here p. 94.

- ^ A b c W. Daniel Wilson: The Faustian Pact. Goethe and the Goethe Society in the Third Reich . DTV, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-423-28166-9 , pp. 36-37, 187-188, 234 .

- ^ Klaus Himmelstein: Eduard Spranger in National Socialism. In: Werner Sacher, Alban Schraut (ed.): People's educators in poor time. 2004, pp. 105–120, here p. 110.

- ↑ Benjamin Ortmeyer: Myth and Pathos instead of Logos and Ethos. 2009, p. 81.

- ↑ Benjamin Ortmeyer: Myth and Pathos instead of Logos and Ethos. 2009, p. 182 f.

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, p. 301.

- ^ Klaus Himmelstein: Eduard Spranger in National Socialism. In: Werner Sacher, Alban Schraut (ed.): People's educators in poor time. 2004, pp. 105–120, here 111.

- ↑ Benjamin Ortmeyer: Myth and Pathos instead of Logos and Ethos. 2009, p. 303 f.

- ↑ Spranger: Cultural Problems in Contemporary Japan and Germany. Speech given in Tokyo on October 9, 1937. In: Education. Vol. 16, No. 6/7, 1940/1941 (March / April 1941), pp. 121–132, here p. 128, Christoph Jahr: The National Socialist Takeover and Its Consequences. In: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (Hrsg.): History of the University under the Linden 1810-2010. Volume 2. The Berlin University between the World Wars 1918-1945. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-05-004667-9 , pp. 312-313.

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, p. 359.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger: Review (without year). In: Eduard Spranger: Collected writings. Volume 10: University and Society. Niemeyer et al., Tübingen et al. 1973, ISBN 3-494-00594-X , pp. 428–430, here p. 430.

- ↑ Benjamin Ortmeyer: Myth and Pathos instead of Logos and Ethos. 2009, p. 395.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger: Berliner Geist. Essays, speeches and notes. Wunderlich, Tübingen 1966, p. 127.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger: Berliner Geist. Essays, speeches and notes. Wunderlich, Tübingen 1966, pp. 121-124.

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, p. 303.

- ^ Siegward Lönnendonker : Free University of Berlin. Foundation of a political university. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-428-06490-9 , pp. 51-78.

- ↑ James F. Tent : The Free University of Berlin. A Political History. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 1988, ISBN 0-253-32666-4 , p. 19.

- ↑ James F. Tent: The Free University of Berlin. A Political History. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 1988, ISBN 0-253-32666-4 , p. 20.

- ↑ Wolfgang U. Eckart : Ferdinand Sauerbruch - Master Surgeon in the Political Storm , Springer Verlag Wiesbaden 2016, On Eduard Spranger and Ferdinand Sauerbruch P. 44, ISBN 978-3-658-12547-9 , Ferdinand Sauerbruch Online Resource 2016

- ↑ a b c James F. Tent: The Free University of Berlin. A Political History. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 1988, ISBN 0-253-32666-4 , p. 22.

- ↑ James F. Tent: The Free University of Berlin. A Political History. Indiana University Press, Bloomington IN et al. 1988, ISBN 0-253-32666-4 , pp. 25-30; Pyotr I. Nikitin : Supplements: On the history of the establishment of the Free University. In: Manfred Heinemann (Ed.): University officers and the reconstruction of the university system 1945–1949. The Soviet occupation zone (= Education and Science Edition. Vol. 4). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-05-002851-3 , p. 412 ff.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger's letter of July 20, 1945 to the deans, in: UA der HUB, Phil. Fac., Faculty Affairs 1945 to 1946, No. 8, Sheet 3.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger: Berliner Geist. Essays, speeches and notes. Wunderlich, Tübingen 1966, p. 35.

- ^ Siegward Lönnendonker: Free University of Berlin. Foundation of a political university. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-428-06490-9 , p. 68.

- ^ Siegward Lönnendonker: Free University of Berlin. Foundation of a political university. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-428-06490-9 , pp. 75, 67 ff.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger: Berliner Geist. Essays, speeches and notes. Wunderlich, Tübingen 1966, p. 37.

- ^ Eduard Spranger: Brief Self-Representations I (1961). In: Hans Walter Bähr, Hans Wenke: Eduard Spranger. His work and his life. 1964, p. 20.

- ^ Klaus-Peter Horn: Competition and Coexistence. In: Klaus-Peter Horn, Heidemarie Kemnitz (Hrsg.): Pedagogy under the lime trees. Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden 2002, ISBN 3-515-08088-0 , p. 228.

- ↑ Quoted from Hans Wenke: State and education. In: Die Zeit , No. 26, June 27, 1957, article on Spranger's 75th birthday; Eduard Spranger: Celebration of the National Remembrance Day. Bonn September 12, 1951. In: Parliament , supplement of September 19, 1951.

- ↑ Spranger: Pestalozzis forms of thought. 1947.

- ↑ Spranger: Goethe. His spiritual world (= The Books of the Nineteen. Vol. 150, ZDB -ID 1189806-9 ). Wunderlich, Tübingen 1967.

- ↑ See Joachim Ritter et al. (Ed.): Historical dictionary of philosophy. Volume 1: A - C. 1971, p. 932.

- ^ Spranger: Wilhelm von Humboldt and the idea of humanity. 1909, p. 492 f.

- ^ Spranger: Wilhelm von Humboldt and the idea of humanity. 1909, p. 6 f.

- ↑ Spranger: The educational value of local history. Speech for the opening session of the study group for scientific local history on April 21, 1923. Hartmann, Berlin 1923 (7th edition (= Universal Library 7562). Reclam, Stuttgart 1967; reprinted in: Eduard Spranger: Gesammelte Schriften. Volume 2: Philosophical pedagogy . Niemeyer, among others, among others Tübingen 1973, ISBN 3-494-00591-5 313 et seq., pp 294-319, here p, especially pp. 317).

- ↑ Spranger: Life forms. 1921, p. 265.

- ^ Spranger: Appeal to Philology. In: Spranger: The Current State of the Humanities and School. Speech given at the 53rd meeting of German philologists and school men in Jena on September 27, 1921. Teubner, Leipzig et al. 1922, p. 7.

- ↑ See Spranger: Geist und Seele. In: Leaves for German Philosophy. Vol. 10, 1937, ZDB -ID 501558-3 , pp. 358-383, here p. 374 f.

- ↑ Spranger: Psychology of Adolescence. 24th edition. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1955, p. 19.

- ↑ Spranger: Psychology of Adolescence. 24th edition. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1955, p. 23 f.

- ↑ Arnd Krüger : Education through physical education or "Pro patria est dum ludere videmur", in: R. DITHMAR & J. WILLER (eds.): School between Empire and Fascism. Darmstadt: Wiss. Buchgesellschaft 1981, pp. 102-122. ISBN 353408537X

- ^ The correspondence between Carl Diem and Eduard Spranger. Edited by Helmut E. Lück and Dietrich R. Quanz. With the collaboration of Walter Borgers. St. Augustin: Richarz ISBN 3-88345-655-1 . (= Publications of the German Sport University Cologne, vol. 31)

- ↑ See e.g. B. Ulrich Herrmann: Spranger, Eduard. In: Walter Killy (Ed.): Literaturlexikon. Vol. 11, 1989, p. 118.

- ↑ Spranger: Life forms. 1921, p. 172.

- ^ Quote from Peter Drewek: Eduard Spranger. In: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth (ed.): Classics of Pedagogy. Vol. 2. 2003, pp. 144 f.

- ↑ Spranger: Basic education, vocational training, general education (= basics and basic questions of education. Vol. 9/10, ZDB -ID 966229-7 ). Concerned and introduced by Joachim H. Knoll. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1965, p. 34.

- ↑ Alban Schraut: Biographical Studies on Eduard Spranger. 2007, p. 361.

- ^ Yearbook of the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin. 1963, ZDB -ID 2495-8 , p. 60.

- ^ Honorary members of the Association for Patriotic Natural History in Württemberg

- ↑ Isabel Feuchert, Pit Oertel u. a. (Edit): Finding aid. Minutes of the Philosophical Faculty (PDF; 933 kB). University archive of the Free University of Berlin (holdings signature PhilFakProt), Berlin September 2014, p. 17.

- ↑ See the almanac of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Bd. 113, 1964, ISSN 0078-3447 , p. 494, and the yearbook of the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin. 1963, p. 60.

- ↑ a b c Falk Reimer: Landau: School was named after anti-Semite In: Die Rheinpfalz , June 14, 2017, accessed in March 2019.

- ↑ Andreas Jordan: Bäumer and Spranger are not role models for young people. In: Gel Center. Portal for city and contemporary history. Created in March 2012, amended in July 2017, accessed in March 2019.

- ↑ a b c d Sabine Schilling: “Process must not be completed”. In: Die Rheinpfalz , May 19, 2018, accessed March 2019.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Laufs: Vocational college no longer wants to remember Eduard Spranger. In: WAZ , April 24, 2018, accessed March 2019.

- ↑ a b Mayor Martina Rudowitz welcomes the name change for the Buersche Vocational College. Press release of the SPD Gelsenkirchen, June 26, 2018, accessed March 2019.

- ↑ Manfred Becht: Eduard Spranger School can choose a new namesake. In: Frankfurter Neue Presse , June 9, 2017, accessed March 2019.

- ↑ Homepage of the school , accessed in February 2020.

- ↑ Felizitas Eglof: A school has a different name In: Stuttgarter Zeitung , February 27, 2019, accessed in February 2020.

- ↑ Homepage of the school , accessed in March 2019.

- ↑ Paula Janke, Lena Wind: Eduard Spranger - “No idea who that is!” In: Die Rheinpfalz , 23 August 2017, accessed in March 2019.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Spranger, Eduard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German educator, psychologist, philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 27, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lichterfelde , today Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | 17th September 1963 |

| Place of death | Tubingen , Baden-Wuerttemberg |