New department of the National Gallery Berlin in the Kronprinzenpalais

The New Department of the Nationalgalerie Berlin in the Kronprinzenpalais was the world's first public collection of contemporary modern art of the 20th century. It was founded in 1919 by the director of the Berlin National Gallery Ludwig Justi and existed until the National Socialists came to power . With limited operation, it remained in existence until the Degenerate Art exhibition in 1937. The gallery in the Kronprinzenpalais was best known as the most comprehensive collection of expressionist art .

Modern art in the Nationalgalerie Berlin until 1919

At the end of the 19th century, the then director Hugo von Tschudi opened the National Gallery of Modern and European Art and acquired paintings by French Impressionists . With this courageous arbitrariness he came into conflict with Wilhelm II , who issued a cabinet order in 1898, according to which all new purchases and gifts had to be presented to the emperor and agreed with a conservative art commission headed by Anton von Werner . The dispute over the direction of the Nationalgalerie smoldered for a whole decade until Tschudi was finally dismissed.

His successor was Ludwig Justi, who immediately after his appointment in 1909 postulated in the memorandum Die Zukunft der Nationalgalerie the need to divide the holdings into the main building, a museum of 20th century art and a portrait gallery. In 1911 he succeeded in dissolving the state art commission and set up a small purchasing commission according to his ideas. The first steps to modernize the Nationalgalerie began before the First World War : the battle paintings were given to the armory , the naval paintings to the new museum in Wilhelmshaven . During the war, Justi managed to put together an appropriate collection of the long-established German impressionists with works by Max Liebermann , Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt .

The gallery in the Kronprinzenpalais 1919–1933

The exhibition concept of the Gallery of the Living

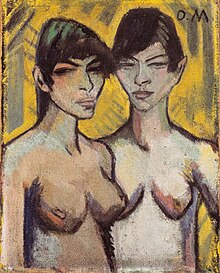

When the emperor's right of veto expired after the First World War, Justi had a free hand for the contemplated collection of contemporary art. The financial hardship paradoxically favored the programmatic focus on contemporary art, because the already established impressionist paintings were no longer affordable. As a result, the buying policy concentrated on the emerging expressionism, for which there were still few interested parties on the art market. Immediately after the end of the war, in December 1918, Justi acquired works by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff , Otto Mueller , Max Pechstein , Erich Heckel , Ernst Barlach , Oskar Kokoschka , Franz Marc and Wilhelm Lehmbruck . The acquisitions led to a controversy with the official commission for the purchase of new works. The acquisition of Oskar Kokoschka's picture Die Freunde led to a scandal, as a result of which the commission disbanded.

The lack of finance did not allow for the modern new building that Justi wanted, but the vacated Hohenzollern palaces provided the necessary space. The functionally redesigned Kronprinzenpalais Unter den Linden took over the new department of the National Gallery. The unresolved ownership situation in relation to the former Prussian royal family and the usage contracts, which were limited to only one year, initially prevented planned modifications.

It was not until 1927 that the Kronprinzenpalais finally became the property of the National Gallery. The financial possibilities, however, hardly allowed structural changes. The very simple furnishings on the third floor consisted of simple paper wallpapers and rough wooden floorboards. The partitioning of the walls consisted of a 30 cm wide colored base and a simple, functional hanging bar. It was precisely this puristic room design that proved to be beneficial for the exhibition concept, while the rooms on the lower two floors prevented the works of art from developing freely, although here too the extensive wooden fixtures, mirrors and cluttered chimneys had been removed where possible. The fabric wallpapers from the Hohenzollern era could only be suspended after 1927.

The opening of the new gallery took place on August 4, 1919. Most of the rooms on the ground floor were furnished with older holdings - including works by Liebermann, although Justi had a well-known personal enmity with him. One room was dedicated to the French impressionists Édouard Manet , Claude Monet , Paul Cézanne , Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir , another to the Berlin Secession . There were also works by artists such as Vincent van Gogh , Edvard Munch , Ferdinand Hodler , Max Slevogt , Aristide Maillol and others.

The second floor formed the real centerpiece with the Expressionists : the Dresdner Brücke artists Erich Heckel , Ernst Ludwig Kirchner , Otto Mueller , Max Pechstein , Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff , the painters Franz Marc and Christian Rohlfs , the Bauhaus artist Lyonel Feininger and sculptures by Ernst Barlach and Wilhelm Lehmbruck . But also Vincent van Gogh , Paul Gauguin and Oskar Kokoschka , French pointillists and James Ensor , later works by Edvard Munch , Ferdinand Hodler and Aristide Maillol were added.

One of the innovations in the exhibition concept was to dedicate individual rooms to the oeuvre of an artist or a group of artists, such as the Blauer Reiter or Die Brücke . Franz Marc (together with sculptures and graphic works by Lehmbruck), Emil Nolde , Erich Heckel and, in 1933, Max Beckmann were given such a monographic room . Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff shared a hall. If possible, a self-portrait or a portrait by another artist of the same group of works was also taken. Otherwise there was no chronological or systematic breakdown.

The rooms themselves were simply furnished, a wide colored base and a functional hanging rail were the only architectural elements. The works were grouped freely under a simple strip of paper with the artist's name on it. Erich Heckel's “Ostend Madonna”, painted on two sheets of canvas for a Christmas party for the wounded in 1915, was specially positioned in front of a curtained window so that it could be seen through the doorways of all five rooms on the upper floor (the altar was destroyed by fire in 1945). Individual works by Kandinsky , Paul Klee , Lyonel Feininger , August Macke , Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and Ernst Barlach completed the exhibition.

Overall, the gallery in the Kronprinzenpalais had the best and most comprehensive collection of contemporary, especially expressionist art. With this permanent exhibition space for modern art, which is unique worldwide, Ludwig Justi created the type of museum for contemporary art that is still current today and served as a model for other museums.

Another novelty, half for conceptual, half for financial reasons, was the use of numerous loans and the organization of temporary exhibitions. As a result, the museum staging was in constant motion. Critics therefore disparagingly referred to the Gallery of the Living as an experimental gallery .

The charisma of the Kronprinzenpalais

Despite or because of all these innovations, the concept of the Kronprinzenpalais had a worldwide appeal. The forty or so German museums that collected modern art were based on his concept and in 1929 it served as a model for the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art in New York , while there was no comparable institution in other European countries. In 1927, Alfred Barr , the legendary founding director of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, visited the Kronprinzen-Palais and was enthusiastic about the concept of setting up a museum exclusively for modern art.

From the start, Justi received criticism from many sides for his pioneering work. This was based partly on art theory, partly on political grounds: On the one hand, the impressionist painter Max Liebermann , President of the Academy of the Arts , rejected expressionist painting and was supported by the academy and influential magazines and newspapers. Liebermann was reserved, even before the Nazis , the painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde , Erich Heckel , Edvard Munch , Lyonel Feininger and Vincent van Gogh to be called "existences beyond civilization".

On the other hand, Justi was exposed to hostility from conservative and increasingly völkisch National Socialist opponents. But criticism also came from the political left, because Justi had a national-conservative idea of a leading role in German culture despite his progressiveness and inclusion of other European countries. Despite all the programmatic opening, Justi continued to see the National Gallery, and thus also the Kronprinzenpalais, as a self-portrayal of Germany as a cultural nation .

The museum and Justi also played a pioneering role in the public discussion of modern art. From 1930 to 1933 the magazine Museum der Gegenwart claimed to be the mouthpiece for everyone interested in modern museum concepts, acquisitions, museum architecture and modern art in general. Alfred Barr was also a corresponding member. In 1929 the “Association of Friends of the National Gallery” was founded, which subsequently enabled the purchase of numerous paintings, including works by Picasso , Braque and Juan Gris .

Berlin Museum War

Justi and the art critic Karl Scheffler had the bitterest dispute . This public debate has become known as the Berlin Museum War. Under this title, Scheffler published a book in 1921 in which he tackled Justi, whom he had initially supported, harshly and polemically. While Scheffler had more modern ideas about the autonomy of images in the museum in the museum concept (he pleaded for white walls as a neutral background, for example), he represented the older impressionists over the expressionists, who were Justi's main focus. Justi paid Scheffler with the same coin in the font Habemus papam! back, and both subsequently used their respective magazines Museum der Gegenwart and the high-circulation art and artists that Scheffler published at Cassirer to fight their war.

Since this guerrilla war lasted until 1933 and polarized the public interested in modernity , both sides failed to form themselves against the simultaneously increasing criticism of nationalist propaganda. In April 1932 Scheffler had still written: Time will hold a terrible scrutiny there [in the Kronprinzenpalais] anyway. This meant a future quality judgment that not many Expressionists would withstand - tragically, his prophecy was supposed to be right in a much more concrete way. In 1933 the Museum of the Present and Art and Artists were banned at the same time .

The time of National Socialism

Justis dismissed

Liebermann and the French Impressionists returned to the main building of the Nationalgalerie in January 1933 and were thus programmatically removed from the contemporary art series. For this purpose, paintings from the Novecento Italiano , i.e. from the area of the pro-avant-garde art policy of fascist Italy , were added to the collection (including pictures by Modigliani and Chirico ). Both measures resulted in fierce criticism from the political left, which Justi accused of reinterpreting Expressionism in the folkish sense as the epitome of German art and thus serving National Socialist positions. This perception can be proven by Justi's statements. To what extent the rapprochement resulted from tactical considerations is difficult to assess. After all, the Kronprinzenpalais was at the center of the cultural-political discussion and was dependent on politics. At the same time, the Völkischer Beobachter , the Deutsche Kulturwacht and other National Socialist publications attacked the gallery as the epitome of "Jewish cultural Bolshevism" with ever increasing intensity. When the restructured gallery reopened, the Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring visited the Kronprinzenpalais for the first time together with the Italian Ambassador Cerruti , who hardly tried to hide his displeasure with the Expressionists on display.

On February 15, 1933, the redesigned collection was opened to great public interest. The Kronprinzenpalais was one of the most visited museums in Berlin.

After the takeover, the attacks of the concentrated conformist press then immediately to the Crown Prince's Palace. In March 1933, museum officials formulated a letter of protest to the German minister of education, in which they stood up for director Ludwig Justi, who was accused by the National Socialists of promoting “Jewish art” and “Marxist business”. At first, however, there was also an attempt to establish expressionism, especially that of the bridge, as statecraft , something that ministers of culture Rust and Goebbels kept open. Justi also took part in the rally against the art reaction of the National Socialist Student Union on June 29, 1933 and believed that an alliance with the Nazis in favor of avant-garde art was possible. Only two days later, however, on July 1, 1933, he was released from his position without giving any reason and was forcibly transferred to the art library .

The short era of Schardt

Alois Schardt initially appeared to be suitable as a provisional successor to the responsible bodies in the Prussian Ministry of Culture , who on the one hand had built up one of the most important collections of modern art in the Moritzburg Municipal Museum in Halle (Saale) (as the successor to Max Sauerlandt ) and on the other was a leading member of the National Socialist League for German culture was. He had dealt early on with alleged racial peculiarities in art and tried to defend “Nordic” expressionism in the folkish sense as a continuation of Gothic and Romantic German art. Schardt was close to the ideologies of the National Socialists, but appeared essentially apolitical and naively convinced.

After the Minister of Education and Culture Rust had refused the first hanging, Schardt tried to defuse the attacks by compromising the hanging. The basement was left to the romantics like Caspar David Friedrich , Blechen and Runge , the middle floor and the like. a. Marées and Feuerbach , only upstairs, were exhibited as the high point of the “German desire for art” (according to Schardt), the Expressionists: Nolde, Barlach, Marc, Kokoschka, Lehmbruck, the bridge and the Blue Rider. All exhibited artists had to provide proof of Aryan . Van Gogh and Munch, who are considered “Germanic”, were singled out among the non-German artists. The works of the New Objectivity came to the neighboring Prinzessinnenpalais , many Expressionists were removed from the exhibition. Despite the redesign, the collection was not approved by the ministry and Schardt was dismissed on November 20, 1933 after he had previously been banned from speaking or writing in public. In 1939 he finally went into American exile, where he worked at Marymount College in Los Angeles .

Rescue attempts by Eberhard Hanfstaengl

In November 1933 Eberhard Hanfstaengl was appointed director of the National Gallery. The New Department was defused again in order to offer its critics as little open to attack as possible: Expressionist portraits were exchanged for still lifes or landscape pictures by the same artist, and many abstract pictures went straight to the magazine to be on the safe side. The works of the Paris School (Picasso, Braque and others), against which there had been violent polemicism, were removed from the collection. Yet the press reaction continued to be devastating. After all, Hanfstaengl still bought pictures by Nolde, Kirchner and Schmidt-Rottluff.

The first seizures took place in 1935. The collection remained open until the Olympic Games in 1936 and attracted crowds of visitors during the competitions with a special exhibition entitled “Great Germans in Portraits of their Time”, many of whom also visited the upper floor, which was accessible all the time. After the games, however, the "temporary" closure of this department followed on October 30, 1936 and only interested visitors were allowed to enter this part of the collection. Samuel Beckett, for example, visited the rudimentary Kronprinzenpalais on December 19, 1936 and noted in his diary: “Unspeakable Sittenausstellung” and on January 20, 1937: “Ground floor: Chirico, Modigliani girls, Kokoschka, Feininger, up the stairs Sintenis, Kollwitz and Corinth” .

In February 1935, the Gestapo confiscated 64 works of modern art from the Max Perl auction house on Unter den Linden, including paintings by Max Pechstein, Otto Mueller and Karl Hofer. The Gestapo entrusted Hanfstaengl with the task of sorting out a small part as "culturally and historically significant", but destroying the rest. Hanfstaengl saved 5 paintings and 10 drawings, the rest had to be burned under supervision on May 20, 1936 in the boiler room of the Kronprinzen-Palais.

Degenerate art

In keeping with its importance, the Kronprinzenpalais fell victim to the Degenerate Art campaign like no other museum in 1937 . The gallery was completely closed on July 5th, and a Goebbels decree ordered the selection of works of so-called decay art for the purpose of an exhibition. Since Hanfstaengl refused to work with the commission headed by Adolf Ziegler , he was given leave of absence on July 26, 1937. Paul Ortwin Rave , who headed the Schinkel Museum and worked with Justi, succeeded him on a provisional basis .

A total of 164 pictures, 27 sculptures and 326 drawings from the National Gallery were confiscated for the Degenerate Art campaign, which primarily affected the Kronprinzenpalais. The works did not return after the “Degenerate Art” exhibition , but were sold abroad. The auction at the art dealer Fischer in Lucerne brought only low prices for many works due to the quantity on offer and the reservation of many collectors to acquire paintings from Nazi Germany. In this action, the National Gallery lost a total of 435 works. In his private life, for example, Göring had nothing to complain about and had a number of works confiscated for himself, including those by van Gogh, Munch and Marc's Tower of the Blue Horses . Of the unsold “degenerate” works of art, 1004 paintings and 3824 paper works were burned on March 20, 1939 in the courtyard of the Berlin main fire station as part of an “exercise”.

The end of the collection

At the beginning of the war, all the houses in the Nationalgalerie were closed and the pictures were relocated - initially in the basement, later in the Reichsbank and the flak towers , of which the one in Friedrichshain burned out. Finally, when the warfare intensified, the works of art were evacuated to the salt mines of Central Germany. Depending on the occupying power that occupied the depots first, the works of art ended up in Wiesbaden , Braunschweig , Berlin or the Soviet Union after the war . But there were also losses through looting by the population or by soldiers. The current locations of 49 works are known: other museums, German, American and Greek private collections.

The collection that had become world famous in just a few years was completely lost in an even shorter time.

After the war, the Nationalgalerie, whose director was again Ludwig Justi, and the 20th century urban gallery founded in West Berlin tried to close the gaps that had arisen. The Neue Nationalgalerie , which opened in 1968, expressly ties in with the tradition of the collection in the Kronprinzenpalais.

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1921 Ernst Ludwig Kirchner exhibition with 50 works by the artist.

- 1922 Franz Marc exhibition on the entire upper floor.

- 1923 Paul Klee's first retrospective. Exhibition Lovis Corinth on the occasion of his 65th birthday in two complete floors. Corinth describes the Kronprinzen-Palais as "the only one in the world".

- 1924 Otto Dix solo exhibition (watercolors and drawings).

- 1927 Edvard Munch retrospective with 244 exhibits. In 1892 a Munch exhibition in Berlin was so shocking that it had to be closed prematurely. Opposing reactions led to the founding of the Berlin Secession . With the retrospective in the Kronprinzen-Palais, the 64-year-old Munch experiences a late reparation.

- 1928 Van Gogh exhibition with 143 works.

- 1931 Retrospective on the 60th birthday of Lyonel Feininger.

- 1932 Emil Nolde exhibition on the 65th birthday of the artist.

literature

- Sven Kuhrau, Claudia Rückert (ed.): The German art. The Berlin National Gallery and National Identity 1876–1997. 1998, ISBN 90-5705-093-5 .

- Alfred Hentzen: The Berlin National Gallery in the Picture Storm . Cologne, Berlin 1971. ISBN 3-7745-0254 (previously published under the title The End of the New Department of the National Gallery in: Jahrbuch Preußischer Kulturbesitz, VIII / 1970, pp. 24–89)

- Alexis Joachimides: The museum reform movement in Germany and the emergence of the modern museum 1880-1940. Dresden 2001, ISBN 90-5705-171-0 .

- Ludwig Justi : Becoming - Working - Knowing. Life memories from five decades. Edited by Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Kurt Winkler. Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-87584-865-9 .

- Art in Germany 1905–1937. The lost collection of the National Gallery in the former Kronprinzenpalais. Documentation, selected and compiled by Annegret Janda and Jörn Grabowski (picture booklets of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, issue 70/72), Berlin 1992.

- Peter-Klaus Schuster (Ed.): The National Gallery. Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-8321-7004-9 .

- Kurt Winkler: Ludwig Justi - The Conservative Revolutionary. In: Avant-garde and Audience. On the reception of avant-garde art in Germany 1905–1933. Edited by Henrike Junge. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 1992, ISBN 3-412-02792-8 , pp. 173-185.

- Kurt Winkler: The magazine Museum der Gegenwart (1930-1933) and the musealization of the avant-garde. Museum and contemporary art at the end of the Weimar Republic. Phil. Diss. Freie Universität Berlin, 1993, ISBN 3-8100-3504-1 .

- Kurt Winkler: Ludwig Justi's concept of the contemporary museum between avant-garde and national representation. In: The German Art… National Gallery and National Identity 1876–1998. Edited by Claudia Rückert and Sven Kuhrau. Amsterdam 1998, ISBN 90-5705-093-5 , pp. 61-81.

- Kurt Winkler: Museum and Avant-garde. Ludwig Justi's magazine "Museum der Gegenwart" and the musealization of Expressionism. Opladen 2002, ISBN 3-8100-3504-1 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Pictures chronicle. In: Art and Artists. April 1932. Quoted from: Annegret Janda, Jörn Grabowski : Art in Germany 1905–1937 , p. 19.

Coordinates: 52 ° 31 '2 " N , 13 ° 23' 49" E