Horst Wessel Lied

The Horst-Wessel-Lied is a political song that was initially (from around 1929) a battle song of the SA and a little later became the party anthem of the NSDAP . It bears the name of the SA man Horst Wessel , who wrote the text between 1927 and 1929 on a melody presumably from the 19th century.

After the takeover of the Nazi party, the song served, along the lines of Giovinezza in Fascist Italy, de facto as a second German national anthem . The song was banned by the Allied Control Council in 1945 after Germany's defeat in World War II . This prohibition is still in force in Germany today due to Section 86a of the Criminal Code . In Austria , similar provisions apply due to Section 3 of the Prohibition Act 1947 .

history

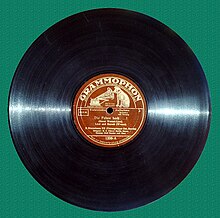

The Horst-Wessel-Lied was published in August 1929 by the NSDAP organ The Attack with the title Die Fahne hoch! printed as a poem. As George Broderick credibly conveyed, Wessel had used the Königsberg song sung to the same melody by the reservists of the German warship “ Königsberg ” as a text template . This was widespread in volunteer corps such as the Bund Wiking or the Ehrhardt Marine Brigade , in which Wessel was a member. It began with the verse “Gone, all the beautiful hours are over” and contains phrases like this: “The team is ready to leave” (changed from Wessel to “We are all ready to fight”). Some of the formulas that Wessel used are reminiscent of models from socialist and communist workers' songs , such as the “last stand” of the International . The musicologist and National Socialist cultural functionary Joseph Müller-Blattau wrote in a musicological magazine in 1934: "Here was the melody that could juxtapose the dashing swing of the 'Internationale' with primordial German."

Shortly after Wessel died on February 23, 1930 as a result of a gunshot wound inflicted on him by Albrecht Höhler , a member of the Red Front Fighter League, the lyrics were again published on March 1 in the Völkischer Beobachter under the heading “Horst Wessel's greeting to the coming Germany ”. The song soon became the official party anthem of the NSDAP and the "Gospel of the Movement" (according to Wessel's sister Ingeborg ). After the National Socialists came to power, it was sung as a quasi-official national anthem by order of Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick on July 12, 1933, immediately following the first stanza of the Deutschlandlied . Adolf Hitler rejected the formal promotion of the song to the national anthem .

melody

According to Section 86a of the Criminal Code, the song in Germany now falls under the mark of unconstitutional organizations , so distribution is prohibited. This is especially true of the melody of the song. This means that the interpretation of the melody with changed text, but not the identical song by Wildschütz Jennerwein in the opening bars , is illegal.

Acts which serve to educate citizens, to ward off unconstitutional efforts, art, science, research, teaching or reporting on contemporary events or history or similar purposes are included in the so-called social adequacy clause ( Section 86 (3) StGB) except. It depends on the overall assessment of the meaning and purpose of the illustration in the context of the overall presentation.

In the "official" version in the songbook of the National Socialist German Workers' Party of the central publishing house of the NSDAP , only the melody is notated without harmonization.

Origin of the melody

There are many speculations about the original origin of the melody, none of which have been conclusively proven to this day. It was evidently associated with sailor and soldier songs for a long time before the Königsberg song mentioned above and thus found some distribution, at least in northern Germany.

In the Empire , the melody was also sung to the bench song I once lived in the German fatherland . The legend persists that the latter comes from the opera Joseph et ses frères (1807) by the French composer Étienne-Nicolas Méhul . This claim can not be substantiated on the basis of the score , but is used, among other things, to circumvent the above-mentioned prohibition of the melody. After a (given the time of origin critically questioning) theory of music writer Alfred Weidemann from 1936 to one of the most important "Urmelodien" one of the song by Peter Cornelius in 1865 in Berlin belonged and recorded barrel organ melody have been.

In his book Hitler - The Missing Years , the former close Hitler employee Ernst Hanfstaengl claims that the song is based on a Viennese cabaret song from the turn of the century. The beginning of the song has similarities with the Upper Bavarian folk song Der Wildschütz Jennerwein ( ) from the 19th century. A similarity with the melody of the English hymn How Great Thou Art (also known as O store Gud in Sweden ), which has been documented since around 1890, can also be determined.

However, it remains controversial in research how sound and meaningful such melodic "lineages" are. In their restriction to simple, catchy stylistic devices of European music of the 19th century, the above-mentioned melodies are similar, but similarities can also be explained by the fact that the use of always the same expressive possibilities allows such parallels to be expected.

Musical characteristics

Due to its technical characteristics, the melody proves to be particularly well suited for the purpose it was supposed to fulfill in the context of Nazi propaganda . Its pitch range is a ninth , it is purely diatonic (does not require any tones that are not part of the ladder ) and can only be accompanied by the three functional basic chords (i.e. tonic , subdominant and dominant ). In practice, all this means that the Horst Wessel song can also be performed by less experienced musicians. Arrangements and performances such as the amateur brass bands used in the context of SA rallies can thus be easily realized.

A remarkable number of musical possibilities are exploited within this narrow framework. The end of the second line in the example above is particularly effective, where the inversion of the tonic triad covers almost the entire circumference of the piece. In contrast to the text, which poses problems even from a purely technical point of view, the melody is characterized by a comparatively skilful use of traditional means of expression (such as the rhythm or the melody).

In order to achieve a martial-military effect (which is not necessarily inherent in the melody at first), fanfare - like horn interjections, characterized by triplets , were often used in triad notes during the pauses in the melody or at the beginning of the song.

The repeated use of dots , which is intended to give momentum and cheer listeners or singers, has the song in common with other political battle songs . Another characteristic often encountered in this and similar songs is the fact that the melody reaches the top note, which can be interpreted as a melodic expression of the "impending victory", only after a slow rise in the second half, around to the end of the song to descend. The last two features can be shown particularly clearly using the example of Brüder, zum Sonne, zur Freiheit - a well-known battle song of the labor movement - which has eight dots. The top note F is only reached after a long run-up over the C (measure 4) and the E (measure 6) in the penultimate measure. ( )

The text of the Horst-Wessel-Lied combines - in contrast to Brüder, zur Sonne - the musical effect of "victoriously reaching the top note" with appropriate words only very late. In the second (“Es schau'n auf swastika”) and especially in the third stanza (“Soon Hitler flags flutter”) the correspondence between the text and the melody in the sense described is clear.

Takeover by National Socialism

For the popularization of the Horst Wessel song by the National Socialists, the fact that the melody already enjoyed a certain popularity without being too tightly tied to any of the various earlier texts proved to be advantageous . The earlier versions had also proven their suitability for a relatively wide range of musical arrangements - for example in terms of tempo or instrumentation . The solidarity with the common people, which played an important role in the party's self-portrayal, was also subliminally confirmed by the popular character of the melody.

How much attention was paid to such insignificant details by Nazi propaganda , even after the battle song of the SA (as well as the SA itself) had long since lost its original function, is shown by an instruction from the official communications of the Reichsmusikkammer dated February 15, 1939 : "The Führer has decided that the Deutschlandlied should be played as a consecration song in the time measure ¼ = M 80, while the Horst Wessel song should be played faster as a revolutionary battle song."

Music aesthetic problems

The ban on the melody in Germany is still controversial today. The discussion is sparked by the question of the extent to which a sequence of notes can express the content that a text that was written much later independently formulates or implies.

In the context from which the melody originates (namely the musical language of the early 19th century), it offers a technically satisfactory solution with regard to the demand for simplicity and folklore. An aesthetic contradiction arose when the National Socialists ideologically claimed this melody for themselves and coupled it with a text that was very combative, revolutionary and forward-looking. The artistic achievements of modern times were largely rejected as " degenerate " by the cultural policy of the NSDAP , which is why there was never a collaboration between lyricists and composers based on contemporary standards, as was the case with poets and musicians such as Bertolt Brecht in the politically left-wing spectrum , Johannes R. Becher , Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler was the case.

The latter examples in particular also show how suspicious the authoritarian regimes of this time - regardless of ideological influences - were of contemporary art: In the Soviet Union , too , from the 1930s under Josef Stalin, there was a state-decreed departure from modernism towards classicism and that Traditional styles such as Romanticism and Realism, integrating Socialist Realism , whose musical products are often difficult to distinguish from those of the Nazi cultural scene.

Reception in musicology

National Socialist music researchers soon began to ideologically exaggerate the importance of the simple song. Joseph Müller-Blattau , editor of the Riemann music lexicon from 1939, established "old, typically Germanic melody types" as early as 1933 and came to the conclusion that the new folk song was the "real-root type, which was dignified in the Horst-Wessel song finds shaped ". Ernst Bücken saw in him the "new community song that functions as an echo of a community united in battle and united by him". Werner Korte right away programmatically renounced analytical efforts: “The one who z. B. would subject the Horst Wessel song to a purely musical criticism, d. H. If you wanted to evaluate this melody from the standpoint of the absolute musician, you would come to a judgment formulated in one way or another, which can be just as justified as it is necessary for the song to be irrelevant. All tried and tested methods of critical analysis fail here, as music is not performed as an end in itself, but in the service of a political commitment. ”The neglect of musical analysis was compensated for by unclear and untenable terms such as“ Nordic ”or“ Germanic music ”.

After 1945, the song was hardly mentioned in music and literature for years. It was also no longer included in new editions of song books. In Paul Fechter's History of German Literature , published in 1960, Wessel is no longer mentioned, although the author wrote in 1941 that “Horst Wessel created the defining song of the new era”. The musicologists who were still active at universities could not see an exaggerated, objectively unjustified appraisal of allegedly ethnic elements in music in their pre-war publications. For example, Friedrich Blume , who published an essay on Music and Race in 1938 , shifted all responsibility ten years later to "unqualified, intrusive characters who suddenly appeared". He made the claim that "the serious scientists from Besseler to Blume, Fellerer , Osthoff , Vetter to Zenck were not loyal to their leader, but remained true to their convictions."

It was not until the 1980s that musicology, as can also be seen from the list of literature below, increasingly embraced music under National Socialism .

Lyrics of the song

Battle song of the SA

The text Wessels glorifies the paramilitary sub-organization of the NSDAP, the SA. The SA and the terror it wielded played an important role in the establishment of the National Socialist dictatorship. In the lyrics, however, it is exclusively portrayed as a mass movement in the struggle for freedom and social justice, while the aggressive character of the organization and its pronounced anti-Semitism are not explicitly named.

Raise the flag!

The rows firmly (tightly / are) closed!

SA marches

with a calm (courageous) firm step

|: Kam'raden, shot the

red front and reaction,

marching in spirit

In our ranks with: |

Clear the road for

the brown battalions Clear

the road for

the storm division man!

|: Millions are already looking at the swastika full of hope

The day for freedom

and bread is dawning : |

Storm alarm (/ roll call) is blown

for the last time

!

We are all ready

to fight

!

|: Hitler flags are already (soon) fluttering over the streets (over barricades)

The bondage will

only last a short time! : |

At the end the first stanza was repeated.

Historical background

The lyrics of the song are difficult to understand without a relatively detailed knowledge of the political situation in Germany around 1930, to which Wessel refers. This is not only due to the passages that relate in terms of word choice or intention to circumstances typical of the later years of the Weimar Republic , but also to certain linguistic and “technical” incoherences, which are discussed in more detail below.

The term Red Front called in the former parlance the communists than the fiercest opponents of the Nazis or the SA in the street fighting, especially the fighting organization of the Communist Party , the Red American Legion . The Red Front fighters greeted with raised fists and the exclamation “Red Front” (the association newspaper was also called Die Rote Front ). The expression is z. B. also used in the famous song of the Red Wedding by Erich Weinert and Hanns Eisler .

For today's reader, for whom the equation of National Socialism and right - wing extremism seems natural, it may seem surprising that Wessel's text also defines the NSDAP as “to the right” with the catchphrase reaction . However, this corresponded to the self-image of very many NSDAP supporters and in particular the SA, who saw themselves as members of a social revolutionary movement in just as sharp contrast to the conservative and monarchist forces of the bourgeoisie , such as the German National People's Party (DNVP). It is true that the National Socialists came to power in 1933 in a coalition with these "reactionary" forces (see seizure of power ), and those parts of the party and the SA that understood themselves as social revolutionary were eliminated in the so-called Röhm Putsch in 1934 . This did not prevent the NSDAP from making the Horst-Wessel-Lied the party and second national anthem, which was to be sung on all official occasions.

Sometimes romanticizing, sometimes heroic images with echoes of the military and the revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries make up a large part of the text and idealize to a considerable extent the everyday political life of the time, which was characterized by an extraordinary propensity for violence. Political meetings often ended in street fights or battles, especially between the “fighting organizations” of the radical parties, but also with the police, which could well result in injuries and deaths. The Hitler putsch of 1923 echoes in the formulation of the comrades shot by the “reaction” . The allusion to barricades , as they were erected by the rebels against the governmental order, especially during the July Revolution of 1830 and the March Revolution of 1848, hardly corresponds to reality.

Likewise, the phrase “brown battalions ” suggests that the SA, in their brown uniforms, generally proceeded in large numbers and with military drill. In fact, its members penetrated as often with small, camouflaged thugs as provocateurs in meetings of political opponents - a practice that in the polarized situation during the Great Depression was practiced by many radical groups.

The references to the “Day of Freedom” or the “End of Servitude” express a diffuse feeling that was widespread in the Weimar Republic of being a victim of unjust conditions. This is surprising insofar as the republic had the most liberal constitution that Germany had before then. The enormous social, economic and foreign policy problems that arose primarily as a result of Germany's defeat in World War I and the Treaty of Versailles ( reparations , inflation , occupation of the Ruhr in 1923, etc.) led to conspiracy theories of all kinds and a perception of oppression shared by broad sections of the population Germany through “abroad”, “the system”, “capitalism”, “Judaism” and so on.

Linguistic and stylistic means

It has already been pointed out that the text of the Horst Wessel song emulates the tone of older battle songs of various political origins. Whole text fragments can already be found in pieces from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, although it is still controversial in research to what extent Wessel can actually be accused of plagiarism . In his biography of the writer Hanns Heinz Ewers , who apparently knew Wessel from his studies (he wrote a novel about the life of Horst Wessel in 1932), Wilfried Kugel speculates about the possibility that Ewers could have been the ghostwriter for the lyrics of the song.

The importance of the Horst Wessel song since 1933 was viewed critically or at least occasionally mocked by many Germans - including those who were otherwise no opponents of the Nazi regime. This was partly due to the text itself, where various linguistic weaknesses were criticized: For example, in the verse “Kam'raden, die red front and reaction shot”, it remains unclear who the acting subject is.

The aware of Wessel or unconsciously used archaic style elements, such as the "R" - Stabreim the first verse (in rows , quiet , Comrades , Rotfront , reaction and, in turn, rows ), were, in particular in combination with an abbreviation of modern usage (SA) , perceived as a breach of style .

The second stanza clears the road with the repetition of the command ! a very strong stylistic device. Since the context of the text mentions three groups of people, in order to intensify the overall statement, it would also be expected that the number of these people would increase in the familiar three-step process, i.e. the individual (Sturmabteilungsmann) , the group of champions (brown battalions) and finally the entire German people ( Millions) . Wessel renounces this well-known stylistic device in order not to have to break the rhyme scheme , but thereby risks an involuntarily comical anticlimax .

The style of the Horst Wessel song was criticized, among other things, because it brings together such set pieces in a not always convincing way. The demand for freedom and bread is a typical formula of social revolutionary movements. The bread stands here as pars pro toto for the desire to alleviate material need, whereby the rhetorical figure serves to compensate for the value-theoretical difference between such very concrete claims and the abstract-philosophical concept of freedom. Likewise, texts that address political visions like to use the motif ( topos ) of the dawning day of freedom . Wessel's words combine these two already established expressions in a way that is supposed to arouse well-known associations and emotions, but stylistically unconvincing, especially since the preposition for was inserted twice for metrical reasons .

The glorification of one's own symbols, performed with quasi-religious fervor, is also part of the typical repertoire of political battle songs. In the Horst Wessel song , it is particularly noticeable in the second stanza that the swastika is assigned a role as an expression of the “hope of millions”, as traditionally only given the Christian cross symbol in Europe .

For Wessel, who came from a religious family environment and whose father was a Protestant clergyman, the use of such linguistic images may have been obvious.

Victor Klemperer formulates his "Notes of a Philologist " on the language and style of the song in his work LTI - Notebook eines Philologen , published in 1947 :

“It was all so raw, so poor, equidistant from art and folk tone - 'Comrades who shot the red front and reaction, / marching in our ranks with': that is the poetry of the Horst Wessel song. You have to break your tongue and guess riddles. Perhaps the red front and reaction are nominatives , and the comrades who have been shot are present in the spirit of the 'brown battalions' that have just marched; perhaps also - the 'new German consecration song', as it is called in the official school song book, was rhymed by Wessel as early as 1927 - perhaps, and that would come closer to the objective truth, the comrades are caught because of some committed shootings and march in their own wistful spirit with their SA friends ... Who among the marchers, who in the audience would think of such grammatical and aesthetic things, who would give themselves a headache at all because of the content? The melody and the march, a couple of individual expressions and phrases that address the “heroic instincts”: “Raise the flag! ... Clear the street for the Sturmabteilungsmann ... Hitler flags are soon fluttering ... ': Wasn't that enough to evoke the intended mood? "

Latin translations

As Klemperer shows, a philological dissection of the text can also amount to a political criticism. Walter Jens remembers one such criticism: The teacher Ernst Fritz at the Johanneum in Hamburg had his eleven-year-old students, including Jens, translate the Horst Wessel song into Latin in 1934 . He aimed at the mentioned ambiguity of the construction "shot the red front and reaction". In Latin, this has to be resolved according to one direction, i.e. as nominative or accusative. Fritz let his students try both options, which resulted in two completely different political statements. There were also allusions to the ambiguous tense of "shot":

“So, I will never forget that, he took the Horst Wessel song in Latin class: 'Comrades, the red front and reaction shot, marching in spirit in our ranks' - who is shooting whom here? The comrades on the red front - that's not what Horst Wessel could have meant. The other way around, it sounds extremely unsuccessful. Be that as it may, we want to translate the song into Latin: Sodales qui necaverunt or: Sodales qui necati sunt or maybe even: Sodales qui necabant - lasting past, that is: the comrades from the SA are still killing. That was political grammar. "

A complete Latin translation of the Horst Wessel song , which appeared in the 1933 year of the magazine Das humanistische Gymnasium , resolved the ambiguities mentioned above in the direction intended by Wessel. The author, a certain Arthur Preuss, presumably a teacher of ancient languages at the König-Albert-Gymnasium in Leipzig , rendered the text in a straightforward, metrically bound version, but not singable to the usual melody. The two verses that Ernst Fritz used for his criticism are as follows:

“Et quos rubra acies adversaque turba cecidit,

Horum animae comites agmina nostra tenent.”

In addition to this “neo-Latin” version of the Horst Wessel song , which came up with neologisms such as “rubra acies” ('red battle row' = red front) and 'adversa turba' ('adverse crowd' = reaction), the year also contained other translations of German poems into Latin, for example by Goethe , Eichendorff and Hölderlin . This Latinization of the NSDAP anthem was not an isolated case: Another Latin translation of the song, suggested by Latin students from Amöneburg , appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter ; both works were reprinted in 1934 in the journal Societas Latina , which had dedicated itself to promoting Latin as a living language.

The New Right theory Organ stage printed in 2001, the above-mentioned Latin version of the Horst Wessel Song under the heading Culturcuriosa, Episode 1 from. In the course of a controversy about the planned appointment of the CDU politician Peter D. Krause as Thuringian Minister of Education , this was taken up because Krause was also publishing in the stage at the time.

Relationship between text and melody

Not only Wessel's text itself, but also its connection with the previously known melody led to faults that were smiled at as blooms of style . It is particularly often pointed out that the text “Raise the flag!” In the opening line is used against a downward- facing melody. Since the meter is not kept as consistently as is usually the case with hymns and marching songs , the context of the musical progression results in sometimes nonsensical stresses on syllables that are subordinate to meaning. This is most evident with the word "lasts" in the last stanza.

Since the propaganda of the NSDAP under the leadership of Joseph Goebbels had decided to stylize Wessel as a “ martyr of the movement” and a figure of identification for the “common man from the people”, it deliberately opposed criticism that was devalued as “ educated bourgeoisie ” away.

Dissemination and propaganda use

Joseph Goebbels' role

Joseph Goebbels made a particular contribution to the spread of the Horst Wessel song. An important means was the transfiguration of the author as a martyr and his portrayal as an icon of the National Socialist movement.

In an obituary, Goebbels referred to Wessel as “Christ Socialists” and transferred attributes of the Christ figure to him , from the Last Supper to Ecce homo : He “drank the cup of pain to the end [...] I drink this suffering to my fatherland! […] See what a person! ”This mixture of passion and patriotic struggle could not only be based on the family history, but also on the religious elements mentioned above in the text of the song itself. It had consequences especially for the worship of Horst Wessel among the German Christians : The Horst Wessel song was not only sung as a battle song of the SA and at mass events of the NSDAP, but was also sung in 1933, for example, at a funeral for a dead SA leader from the glockenspiel of the Parochialkirche in Berlin .

Canonization and ritualization

Due to Goebbels' propaganda efforts, the song was able to spread rapidly in National Socialist circles. A clear indication of this are the numerous text variants and additional stanzas that Broderick proves in his extensive source research.

After the National Socialists came to power, this first “wild” phase of expansion ended. Now the work was very quickly included in the official canon of the party and the state and its performance was regulated and ritualized to a high degree . As early as August 1933, as part of further instructions for carrying out the Hitler salute, an order was issued that the Hitler salute should be given when singing the song of the Germans and the Horst Wessel song , regardless of whether the person greeting is a member of the NSDAP or not. An instruction from 1934 also requires a connection with the Hitler salute: "The 1st and 4th stanzas of this new German consecration song are sung with the right arm raised". At all party and state celebrations, the Horst-Wessel-Lied accompanied the first verse of the Deutschlandlied in the form described . Anyone who did not take part in the singing, did not stand up, did not show the Hitler salute or otherwise violated the instructions, for example using the melody as dance music, was threatened with massive sanctions such as denunciation, beatings or arrest. In schools in particular, the song had to be sung regularly, immediately after the first stanza of the Deutschlandlied . A decree of the Reich Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick from 1934 demanded: “At the beginning of school after all holidays and at the end of school before all holidays, a flag is honored in front of the entire student body by raising or lowering the Reich flags while singing a stanza of Germany and Horst-Wessel -The song takes place. ”Numerous biographies of contemporaries attest to the after-effects of such mandatory performances.

The use in schools did not only apply to the ritual singing of the song at festivities. The pupils were taught myths about the time and impact of the work and its author. In a history book from 1942, the role of Wessel and the song in the time of the street fighting with the Red Front is described as follows:

“Police appeared. Horst Wessel had to stop; but fearlessly he closed the rally with a victory salvation on his leader, and on leaving a song roared through the hall, which penetrated everyone's soul like fire: - Raise the flag! The ranks tightly closed! - Horst Wessel wrote it. - Over the next few days, half of his workmates accepted into the National Socialist Party. Richard was there too. But among the communists the leaders raged. Again 15 members renounced them. The words of Horst Wessel had converted them. "

The conflict over copyright

The history of the song under National Socialism was not free of conflict. So the bereaved Wessels, especially his sister Ingeborg, made considerable efforts to benefit from the Wessels factory and his rapid career. She was able to publish numerous editions of a hagiographic illustrated book about Horst Wessel as well as other biographical writings in the party publisher of the NSDAP, but her "attempt to bring an Organino music box with the melody of the song on the market in 1933 was prohibited by higher party officials".

In addition, a copyright dispute broke out over the tune through three judicial authorities between two publishers. A "limited partnership" had published an arrangement of the work without text, but under the title Horst-Wessel-Lied ; Sonnwend-Verlag, which claims to have acquired the exploitation rights from Wessel's survivors, sued the limited partnership for a copyright infringement . In the matter it had to be clarified whether Horst Wessel was to be regarded as the author not only of the text but also of the melody. The highest authority, the Reichsgericht in Leipzig, finally decided on December 2, 1936 that Wessel was not the composer of the song. You can already tell from the discrepancies between text and melody:

"Above all, an artist with a strong musical feeling will adapt to the setting of the words far more than the set-up of the song 'Die Fahne hoch' did. Already the beginning shows a noticeable divergence of word and tone: The text 'Raise the flag' indicates a movement upwards, but the melody moves downwards (without any obvious necessity). "

On the other hand, the court said that the copyright assessment should also take into account the “effect on the people in general, the echo that the creation of sound finds, the mood it creates”. Therefore, if not the protection of the author of the melody, then at least the protection of the musical arranger of a folk tune must be granted to Wessel . With this information, the Reichsgericht referred the case back to the lower court. In his dual state, Ernst Fraenkel cited this court decision as an example of the fact that where the protection of private property was concerned, the “normative state” continued to exist in the Nazi regime.

The research and publications in the course of the trials appeared disruptive to the Reich Propaganda Ministry. Goebbels decided to put an end to further quarrels: “I will stop the processes” (diary entry, June 30, 1937).

In 1940 the Ministry of Propaganda finally banned all performances of this song, which was "sacred by tradition and content" outside of official events, for example in restaurants, by street musicians or in "so-called national potpourris ", which also applied to the melody with or without a text.

Coupling with forms of recognized art music

Nazi propaganda preferred in the time of the LV state ceremonial, monumentalizing uses of the song, as exemplified in the input sequence of Riefenstahl known propaganda film Triumph of the will implemented: the soundtrack of Herbert Windt begins with the sounds of a symphony orchestra , the first one of Windt martial motif from its own intonation. With the appearance of an airplane over medieval Nuremberg, it turns into variations of a not immediately recognizable theme, which soon turns out to be the Horst Wessel song . The music already announces what is shown later in the picture: It is Hitler who is sitting in the plane. Such a symphonic realization coupled the song with the patterns of recognized art music , ennobled it and withdrew it from profane use. A late testimony to such attempts is a four-movement symphony by Friedrich Jung based on classical-romantic patterns, which was premiered in 1942 at the Munich Odeon : It quotes the Horst Wessel song in a string set.

However, purely “external” couplings were more frequent and easier to implement. Performances of classical and romantic musical works, which played no small role in the cultural policy of the National Socialists, were often introduced by Deutschlandlied and Horst-Wessel-Lied . A well-known example of this is a performance of Anton Bruckner's Eighth Symphony a few days after the Wehrmacht invaded Austria by Hans Knappertsbusch .

Goebbels used a very special form of coupling for the special radio reports from the Russian campaign . As he confided in his diary on the day of the attack on the Soviet Union, June 22, 1941, during the night he had experiments with different musical motifs for the signature melody, including those from the Horst Wessel song . The result was that one stayed with the fanfare from Franz Liszt's Preludes ( Russia Fanfare ) , but "plus a short motif from the Horst Wessel song".

Preservation of a historical moment as a state symbol

Details of the text (in particular the line on “Red Front and Reaction” mentioned above) were no longer readily understandable for many younger Germans after a few years of National Socialist rule and were not politically opportune in all cases. In this context, Goebbels thought about a new version in 1937, but ultimately decided not to do so because of the widespread use of the song. The text parts related to the late 1920s now had an effect, since the song no longer had a direct advertising function, more as a time color: the work conjured up memories of the community of the " fighting time " including the victory of the at the end with details suggesting authenticity National Socialism. The combat situation described could later also be applied to the war . During this time the song could be used for new propaganda requirements.

The propagandistic stylization of the Horst Wessel song about the sanctuary can be classified in a number of other similar symbols, such as the blood flag , which allegedly had blood splatters from a National Socialist killed in the Hitler coup . In all of these cases, historical moments of the struggle were preserved and upgraded to quasi-religious symbols of the Nazi state. This procedure is, without prejudice to the considerable differences in content and form, not unusual (the French Marseillaise also preserves a historical moment of the struggle for the state symbol, although of a very different nature). What is striking, however, are the strong religious accents and the considerable proportion of deliberate propaganda staging.

Political use outside of Germany

The song was also the anthem of the Finnish fascist party Isänmaallinen Kansanliike and the British Union of Fascists in the 1920s and 1930s , there under the title The Marching Song .

The Horst Wessel song after 1945

Immediately after the end of the war, the Horst Wessel song was banned across the entire territory of the defeated German Reich by Law No. 8 of the Allied Control Council. In the American zone there was a general ban on singing or playing "German national or Nazi anthems". It was not until 1949 that the relevant laws were repealed. The Horst Wessel song , however, remained banned in Germany and Austria: in the Federal Republic of Germany on the basis of §§ 86 and 86a StGB, in the GDR on the basis of § 220 of the Criminal Code (initially "defamation of the state", later "public disparagement"), in Austria due to the Prohibition Act of 1947.

Sung

Due to the regular performances in National Socialist Germany, the song had certainly left deep marks in the memory and was by no means forgotten. But there are no statistics on performances of the forbidden song after 1945, only a few individual reports.

The journalist Otto Köhler reports that at a traditional meeting of a paratrooper association in Würzburg in 1955, the first stanza of the Deutschlandlied and the beginning of the Horst Wessel song were sung one after the other - admittedly only the first line, then the band switched to the paratrooper song .

In 1957, the Horst-Wessel-Lied was "shouted" several times by drunk public prosecutors, including the First Public Prosecutor at the Schleswig-Holstein Public Prosecutor's Office Kurt Jaager , in the rooms of the Higher Regional Court in Schleswig, including at lunchtime in the canteen of the Higher Regional Court. Only Jaager, who has meanwhile retired, had to endure the consequences: he had "given his disapproving behavior the right to be welcomed and welcomed at his previous office".

At a singing rehearsal in Lingen in 1986 , the singers, as " bouncers ", started a parody of the Horst Wessel song with an apolitical text, so loud that a stroller heard it and wrote a letter to the editor to the local newspaper. The following legal dispute went as far as the Higher Regional Court and led to the current case law that performing the melody is itself a criminal offense. This was justified with general political considerations, in particular the need to maintain a peaceful and stable political balance.

In connection with neo-Nazi activities there were occasional trials in which singing the Horst Wessel song was one of the allegations. Interestingly, this also applies to the GDR: In the years 1987–1989 there were 11 trials against Rostock juveniles under Section 220 of the GDR Criminal Code, a. a. with this charge. Since the 1980s, the Horst Wessel song has also been processed by right-wing rock bands, and various remixes are also circulating on the Internet.

The most spectacular incident in this context occurred in Halberstadt in 2000 . A 60-year-old pensioner complained to the police that a recording of the Horst Wessel song was being loudly played in the apartment above him . The police officers warned the 28-year-old householder, but only for disturbing the peace . The pensioner threatened him that he would report him if he heard "Nazi music" again. Later the two of them met in the stairwell, where the music listener stabbed the pensioner. He asserted self-defense and was acquitted, as this argument could not be refuted, nor could it be proven that the song was playing.

Germany song and Horst Wessel song

Many people knew the direct succession of the first stanza of the Deutschlandlied and the Horst-Wessel-Lied well from the time of National Socialism, where it was practiced many times, especially in schools. The resulting coupling of the two songs turned out to be problematic in the discussion about a new national anthem in the Federal Republic of Germany. The Federal President Theodor Heuss set Konrad Adenauer's wish to make the third stanza of the Deutschlandlied the national anthem, 1952 a. a. opposed to the following reason:

“You are right: I wanted to avoid that in public events with a patriotic accent, regardless of its size or rank, a discord would be heard, because very, very many people of our people Haydn's great melody only as a prelude to it Have 'poetic' and musically inferior Horst Wessel song in mind, the banal melody of which set the march rhythm into a ruin of the people. "

However, Heuss was unable to assert himself with his criticism.

For GDR citizens who had not seen the Deutschlandlied as a national anthem for a long time, the intellectual connection between the Deutschlandlied and the Horst Wessel Lied could continue for much longer. The book author Heinz Knobloch wrote in 1993:

“So it happens, when I hear, have to hear, the 'Deutschlandlied' today, that as soon as the last note has faded, my head continues seamlessly: 'Raise the flag!' I do not want that! It comes by itself. That's how it is when a new government does not want to consistently part with the old. "

But the Hamburg writer Ralph Giordano also felt the same way in 1994:

"... because after the last note of the national anthem I, inevitably and still, have the notoriously following Die Fahne hoch, the ranks of SA bard Horst Wessel firmly in my ear."

As a cipher, quote, reminiscence

In the German film Der Untertan from 1951, based on the novel of the same name by Heinrich Mann , the Horst Wessel song is quoted in addition to the watch on the Rhine and the fanfare of the newsreel in World War II . Since the song was part of the "musical inventory" of the Nazi era, the practice developed in the post-war period to use it as an acoustic backdrop in films, film scenes and radio plays depicting everyday life in Germany and Austria between 1933/1938 and 1945. The Horst-Wessel-Lied only functions as a musical cipher for (neo) Nazism in corresponding scenes from films such as Ralph Bakshi's Die Welt in 10 Million Jahre (1977) or John Landis ' Blues Brothers .

Not only as a musical cipher, but also as a textual set piece, the Horst Wessel song is used time and again to mark right-wing extremist efforts. The best known realization can be found in 1977 in Konstantin Wecker's very successful and popular ballad Willy . The sung refrain "Gestern hams den Willy derschlong" has no musical references to the Horst Wessel song . The spoken text tells how "Willy" hears a guest singing a song in an inn, "something about Horst Wessel". His reaction “Shut up, fascist!” Leads to a sad end: He is killed by the right-wing radical. Above all, the political and moral pathos of the lecture and the main character established the effect of the piece.

Newer uses of the song are mostly motivated by the advertising and provocation effect of the forbidden. On the 1987 album Brown Book by the group Death in June , for example, the title track is a sound collage containing the Horst Wessel song sung a cappella (presumably by Ian Read ) . And computer games like Wolfenstein 3D and Return to Castle Wolfenstein also use the melody.

The song plays a completely different role in the 1980 novel War and Remembrance by the American Herman Wouk . There the protagonist Aaron Jastrow thinks of the song while being transported to the concentration camp: “Those early feelings flood over him. Ridiculous though he thought the Nazis were [in the mid-thirties], their song did embody a certain German wistfulness… ” (rough translation: 'These early feelings flooded him. As ridiculous as he found the Nazis [mid-1930s], you Lied embodied a certain German melancholy ... ')

Parodies

Before 1933

At the beginning of the 1930s, the melody and text excerpts from the Wessel song were so often adopted by communist and social democratic groups and repositioned in their spirit that this led to the assumption that one or the other of these versions was the actual original. However, Broderick proves in his investigation that none of these theses has been convincingly proven so far. Usually it is a matter of individual words or partial sentences that have been exchanged or reformulated in the desired sense, for example when the “brown battalions” become the corresponding “red battalions”. Beyond this political “change of color”, none of the traditional new textings seem to have pursued an explicit artistic claim.

During the time of National Socialism

Similar revised texts circulated underground after the seizure of power. What is new about this type of parody is that it denounces the social grievances caused (or at least not remedied) by the National Socialist regime and in many cases ridicule the unloved “ bigwigs ” by name. A typical example is as follows:

The prices are high, the shops are tightly closed.

Need is marching and we are marching with

Frick, Joseph Goebbels, Schirach , Himmler and comrades.

They are also starving - but only in spirit

Another example is inspired by the assassination of the SA leadership :

Com'rades, shot by the Führer himself,

march in spirit

in our ranks

Another parody was circulating in South Tyrol during the option in the late 1930s. A version was created in Bolzano , inspired by the behavior of Adolf Hitler on his trip to Rome. His train drove past the South Tyroleans waiting in the stations with curtained windows. The guide didn't give the South Tyroleans a look:

The flag up, the windows tightly closed, that's

how you drive through German South Tyrol.

You great hope of all German national comrades,

you, Adolf Hitler, go, go well!

With the unleashing of the Second World War by National Socialist Germany, the tenor of such parodies changed again. From 1939, and especially after the beginning of the Russian campaign in mid-1941, the parody texts (such as one written by Erich Weinert ) mainly turned against the “fascist war”.

The dystopian novel A Cool Million by the American author Nathanael West , published in 1934, offered a very early reception of the Horst Wessel Lied in literature outside the German-speaking area : This is about a certain Lemuel Pitkin, an "All-American Boy" who is shot under strange circumstances. He then became a symbol of the fascist movement of President Shagpoke Whipple, which eventually took power in the USA. At the end of the novel, a parade of hundreds of thousands of American youths on Fifth Avenue sings the Lemuel Pitkin song .

The calf march

One of the best-known parodies of the Horst Wessel song is the Calf March , a piece from Bertolt Brechts Schweyk during World War II (1943). Originally, this drama was to be performed on Broadway with music by Kurt Weill . However, Weill did not think this was promising, so Brecht worked with the composer Hanns Eisler , who set all the songs to music. It was first performed in 1957 in the Polish Army Theater in Warsaw.

The song is introduced in the following situation: In the military prison in Prague there are Czech prisoners who are to be drafted into the military by the Germans. Now the Horst Wessel song is quoted twice: first as a march "from outside", about which the prisoners talk ("That is horrible music." - "I think it is pretty because it is sad and with a dash") , then the slightly changed refrain without music as a “translation”. Finally, Schweyk performs the calf march that was always sung in the Zum Kelch inn :

The calves trot behind the drum. They deliver the

skin for the drum

themselves.

The butcher calls. Eyes tightly closed

The calf is marching with a steady, firm step.

The calves whose blood has already flowed in the slaughterhouse.

They spiritually drag along in his ranks.

You raise your hands,

you show them.

They are already bloodied

and are still empty.

(Refrain)

They are preceded by a cross

On blood-red flags

That has

a big catch for the poor man .

(Refrain)

The stanzas get new text and melody, while the chorus relates lyrically and musically to the Horst Wessel song . A Brechtian alienation effect is achieved here by means of instrumentation and setting as well as a rhythm , melody and harmony that has been changed from the original .

The accompaniment by two pianos, performed by specially prepared instruments, should be reminiscent of an old mechanical piano in a tavern (see above). It is placed unusually far in the bass , which gives the sound image an additional peculiar effect. The accompaniment is deliberately kept even more monotonous than in the original. The rhythmic uniformity is reinforced by omitting the dots that originally gave momentum when the G jumped up to the E ( measure 2 in the music example). The usual harmonization in pure triads is broken for the first time in measure two by the excessive triad ( C + ), which is generally perceived as relatively dissonant . The "persistent" adherence to the key note B in measure five is particularly striking . In contrast to the Horst Wessel song , in which it appears three times, here it appears six times, almost penetratingly. It does not, as might be expected, dissolve into a C in measure six, but forms an extended major seventh chord in the first quarter of measure six . Here it is instructive to realize that the possible use of excessive chords or major seventh chords in the context of the anachronistic art ideology prevailing in the Third Reich seems difficult to imagine (see the section on musical aesthetic problems ). The piece ends on the dominant seventh chord C7 , which, according to the "conventional" understanding of music, actually calls for a resolution into the tonic (here in F major ). The chromatic downward figure of the last bar then only triggers additional alienation and open questions. It almost seems as if the music wants to say to the listener with its own modest means: “I will not allow you your beloved sensual soundscape, the driving rhythm, the usual final triumph in pure C major, and unclouded pure chords. The real consequences of this song in reality are by no means harmonious. "

Brecht's text takes up the military images of the Horst Wessel song , but turns their pathos into the grotesque with the image of the slaughterhouse. This impression is reinforced by the jump between metaphor and non-figurative speech: the calves “raise their hands” (an allusion to the Hitler salute) and “carry a cross ahead”. This corresponds to jumping between the calves as willing victims of the butcher and the perpetrators in the slaughterhouse (“blood-stained hands”), both of which are indistinguishably addressed with the pronoun “she”. Two further picture levels are also introduced with reference to the Horst-Wessel-Lied : As in the entire drama, food plays a decisive role (meat instead of pathetically charged bread as in Wessel). The promise of meat is not kept (the hands “are still empty”). The religious aspect, which was already indicated with flesh and goblet and appears again and again in the drama, is addressed with the preceding "cross" and promptly destroyed again with a slang image ("has [...] a big hook").

The heroic gesture of the Horst Wessel Song is at the singer of the calves march not a heroism of resistance, but the kalkulierende materialism of the "little man", be drawn into the absurd by the big words. This corresponds with Eisler's musical realization, which also refuses to allow heroic dissolution to the “other side”.

There is another setting of the calf march by Paul Dessau in 1943, which is known under the title Horst-Dussel-Lied . Dessau also used the melody of the Horst Wessel song for the chorus, but underlaid the C major of the melody with a bass in G flat major, which is as harmonically distant as possible and is spaced from the tritone . Due to the continuing dissonance that arose in this way, Dessau denounced the song as "wrong", according to Albrecht Dümling .

In political joke

Quotes from the Horst Wessel song, which was ubiquitous during the Nazi era, or at least allusions to it, also played an important role in the cabaret of the time ( Weiß Ferdl , Werner Finck ) and in political jokes . For example, when Goebbels issued the slogan cannons instead of butter in connection with the armament of the Third Reich in 1935 (which was intended to say that the production of consumer goods had to take a back seat to the interests of the armaments industry ), joke counters immediately called the “Horst-Wessel -Butter ”(“ marches in spirit on our bread ”, alluding to the last line of the first stanza).

Also alluding to this line, the soldiers of the Wehrmacht spoke in their hearty soldier language of "Horst-Wessel-Soup" when it was once again very thin as part of the field catering.

Casablanca and Der Fuehrer's Face

In the famous song war scene of the 1942 film Casablanca , the singing German officers are drowned out by the guests in Rick's Café Américain as the latter sing the Marseillaise . The original plan was to have the Germans sing the Horst Wessel song , which in the context would have been an appropriate choice. The producers refrained from this idea due to copyright concerns. In the film, the officers therefore sing Die Wacht am Rhein , a patriotic song from the imperial era, which here functions as a symbol of violence and oppression.

Similar copyright considerations were in the room when the Walt Disney Studios produced the propaganda cartoon Der Fuehrer's Face in 1942 after the USA entered World War II . The film depicts the poor life of Donald Duck in Nutzi Land . A brass band apparently satirizing the SA sings the title song, which was recorded by the parodist and band leader Spike Jones and his City Slickers, which was very popular at the time . Although Der Fuehrer's Face makes no direct reference to the text or the melody of the Wessel song, the song was immediately perceived as a parody, the style of which was all the more blasphemous as it "desecrated" National Socialist icons with childish, frivolous humor.

After 1945

In the immediate post-war period, when the Horst Wessel song was still alive in the consciousness of contemporaries, further parodies were devised. As in previous years, they formulated comments on current problems using melody, meter and text fragments from the former “national sanctuary”. The ban already imposed by the Allied Control Council and the increasing taboo of all individual memories connected with the Nazi era prevented artistic reflection on the song, which was widespread only a short time ago.

Artists, who are granted a certain enfant terrible status in their respective environment, rarely risk a quote from the text or melody of the song, which has been discredited by German history. In his 1967 work Hymnen , the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen processed recordings of national anthems from various countries, including the Horst-Wessel-Lied , as concrete sounds together with electronic sounds .

In his 2003 sonnet about the young America and the old Europeans, Robert Gernhardt severely criticized the foreign policy of the then US government. In the first trio, the poet refers directly to the Horst Wessel song: “Sternbanner hoch! Combat helmets well closed! USA march with a hot young man's kick ”.

Comparable hymns

- Cara al Sol - the hymn of the Spanish fascist Falange movement

- Lied der Jugend (Dollfuß-Lied) - the hymn of the Austrian corporate state

- Maréchal, nous voilà - the hymn of the unoccupied France during the Vichy regime

- Sturmlied (propaganda song of the SA)

Movies

- Ernst-Michael Brandt: "Transfigured, hated, forgotten" - Horst Wessel - dismantling a myth . MDR 1997

CD

- Hymns of the Germans (CD series Voices of the 20th Century ). German Historical Museum , German Broadcasting Archive 1998 dra.de

literature

- Sabine Behrenbeck: The cult around the dead heroes. National Socialist Myths, Rites and Symbols. SH-Verlag, Vierow 1996, ISBN 3-89498-006-0 ; through New edition ibid., Cologne 2011, ISBN 978-3-89498-257-7 .

- George Broderick: The Horst-Wessel-Lied - A Reappraisal First in: International Folklore Review. London 10.1995, pp. 100-127. Text accessible online on George Broderick's site.

- Martin Damus: Socialist Realism and Art under National Socialism . Fischer TB, Frankfurt 1981, ISBN 3-596-21869-1 .

- Peter Diem: "Hakenkreuzler", "Hahnenschwanzler" and their battle songs. (PDF; 455 kB) In: ders .: Die Symbols Österreichs , 1995, pp. 141–144. Text-critical comparison with the Austrian Dollfuss song.

- Manfred Gailus: The song that came from the rectory .. In: Die Zeit , No. 39/2003

- Marion Gillum: Political Music in the Time of National Socialism . Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-932981-74-X .

- Heinz Knobloch : Poor Epstein - How death came to Horst Wessel . Christoph Links, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-86153-048-1 .

- Hermann Kurzke : Hymns and songs of the Germans . Dieterich, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-87162-018-1 .

- Craig W. Nickisch: " Raise the flag!" The Horst Wessel song as the national anthem . In: Selecta. journal of the Pacific Northwest Council on Foreign Languages. Pocatello Id 20.1999, ISSN 0277-0598 , pp. 17-23.

- Thomas Oertel: Horst Wessel - investigation of a legend . Böhlau, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-412-06487-4 .

- Fred K. Prieberg : Music in the Nazi State . Dittrich, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-920862-66-X .

- Dirk Rahe: The social adequacy clause of § 86 Abs. 3 StGB and its meaning for the political communication criminal law. A dogmatic investigation of constitutional law aspects . Dr. Kovac, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-8300-0608-X .

- Neuhardenberg Castle Foundation (ed.): The Third Reich and Music . Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89479-331-7 .

- Joseph Wulf : Music in the Third Reich. A documentation . Ullstein, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-550-07059-4 .

- Joseph Wulf: Literature and Poetry in the Third Reich. A documentation . Ullstein, Frankfurt 1983, ISBN 3-548-33029-0 .

Web links

- Volker Mall: Who actually shot whom? Lesson draft on the topic of Horst Wessel song and calf march . In: Neue Musikzeitung (nmz)

- Texts of different versions in the course of time

- Section 86a and current case law

- Right-wing extremism: symbols, signs and prohibited organizations (PDF) Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. Horst-Wessel-Lied (p. 60) and other songs.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stanislao G. Puliese (ed.): Italian Fascism and Anti-Fascism. A Critical Anthology . Manchester University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-7190-5639-X , here: pp. 18, 54-55.

- ^ Joseph Müller-Blattau : The Horst-Wessel-Lied . In: Die Musik 26, 1934, p. 327.

- ↑ Judgment of the Oldenburg Higher Regional Court of October 5, 1987, file number Ss 481/87, reference: NJW 1988, 351

- ↑ Judgment of the Bavarian Supreme Court of March 15, 1989, file number 3 St 133/88, reference: NJW 1990, 2006

- ↑ EzSt § 86a No. 2; MDR / S 84, 184

- ↑ The "official" version in the songbook of the National Socialist German Workers' Party can be found on the Militaria website usmbooks.com

- ^ Alfred Weidemann: A forerunner of the Horst Wessel song? In: Die Musik 28, 1936, pp. 911f. Quoted in Wulf 1989, p. 270.

- ^ Ernst Hanfstaengl: Hitler - The Missing Years . Arcade, New York 1994, ISBN 1-55970-272-9 .

- ↑ Similarities between the Horst-Wessel-Lied and How Great Thou Art are shown on anesi.com , accessed on February 2, 2010

- ↑ Diether de la Motte: Melodie - A reading and work book . Bärenreiter, Kassel 1993, ISBN 3-423-04611-2 , here: pp. 145ff.

- ↑ Wulf 1989, p. 128.

- ↑ Wolfgang Knies : Limits to artistic freedom as a constitutional problem . Beck, Munich 1967.

- ^ Joseph Müller-Blattau: New ways to care for the German song . In: Die Musik 25, 1933, p. 664.

- ^ Ernst Bücken: The German song. Problems and shapes . Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt, Hamburg undated Here: p. 187.

- ^ Werner Korte: National Music in the New Germany . In: Frankfurter Zeitung of August 11, 1934.

- ^ Fritz Stege : German and Nordic Music . In: Zeitschrift für Musik , 1934, pp. 1269–1271.

- ↑ Friedrich Blume: Music and Race - Basic Questions of a Musical Race Research . In: Die Musik 30, 1938, pp. 736ff.

- ↑ Friedrich flower: balance of music research . In: Die Musikforschung 1/1, 1948, p. 3ff.

- ↑ Friedrich flower: balance of music research . In: Die Musikforschung 1/1, 1948, p. 6.

- ↑ Wilfried Kugel: Everything was passed on to him, he was ... the irresponsible one - the life of Hanns Heinz Ewers . Grupelleo, Düsseldorf 1992, ISBN 3-928234-04-8 .

- ^ LTI - notebook of a philologist . Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1947, p. 259 f.

- ↑ And stay what I am: a fucking liberal . In: Die Zeit , No. 10/1993; interview

- ↑ See for example the following entries in the German National Library: DNB 575665823 , DNB 575665831 , DNB 580228177 , DNB 560798385 .

- ↑ Das humanistische Gymnasium , Volume 44, Issue 6, p. 235.

- ↑ See the extract from the table of contents for the year

- ↑ Cf. Uwe Dubielzig: The new queen of elegies. Hermann Wellers poem "Y". , especially footnote 35; see on Arthur Preuss and his translation also: Klaas Johan Popma: Humanisme en “antihumanisme” . In: Philosophia reforma. Orgaan van de vereniging voor calvinistische wisjsbegeerte , Vol. 28 (1963), Issue 1, pp. 19–57, here specifically: pp. 42–44.

- ↑ stage , Issue 16, December 2001 / January 2002 S. 154th

- ^ Controversy about Peter Krause. Mirror online

- ↑ Quoted from Gailus, 2003.

- ↑ See Gailus, 2003.

- ^ Wolfgang Mück: Nazi stronghold in Middle Franconia: The völkisch awakening in Neustadt an der Aisch 1922–1933. Verlag Philipp Schmidt, 2016 (= Streiflichter from home history. Special volume 4); ISBN 978-3-87707-990-4 , p. 184.

- ↑ Quoted from Broderick 1995, p. 39 (online version).

- ↑ Cases of deprivation of custody by German courts, among other things because of not singing the song by the children, Christian Leeck has compiled in an essay entitled Der Kampf der Bibelforscherkinder about children of Jehovah's Witnesses in the Third Reich, see documentation in the Internet Archive ). Knobloch 1993 shows a photo in which a citizen is led through the streets of Neuruppin with a cardboard sign: "I, a shameless person ... dared to sit down while singing the Horst Wessel song and thus mock the victims of the national uprising." a newspaper report according to which a couple was taken into "protective custody" for five days, who had danced a popular dance (" Schieber ") to the melody of the song . See pp. 133 and 138.

- ↑ Quoted from Hilmar Hoffmann : And the flag leads us into eternity . (PDF) Fischer, Frankfurt 1988.

- ↑ They All Built Germany - A History Book for Elementary Schools . Deutscher Schulverlag, Berlin 1942, 2nd edition 1943.

- ↑ Ingeborg Wessel: Horst Wessel - His life path compiled from photographs . Rather, Berlin 1933.

- ^ Gailus, 2003.

- ^ Decisions of the Reichsgericht, December 2, 1936, § 1b; quoted here from Broderick, Chapter 2.2.

- ^ Decisions of the Reichsgericht, December 2, 1936, § 3c; quoted here from Broderick, Chapter 2.2.

- ^ Ernst Fraenkel: The dual state . First published as The Dual State 1941. The 2nd, revised edition, ed. and a. by Alexander von Brünneck. Europäische Verlags-Anstalt, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-434-50504-0 , p. 135.

- ^ David B. Dennis: "The most German of all operas": The Mastersingers through the Lens of the Third Reich. In: Nicholas Vazsonyi (Ed.): Wagner's Meistersinger. Performance, history, representation . The University of Rochester Press, Rochester, pp. 98-119, here: pp. 98f. As Dennis points out, it is not the Mastersingers overture , as is often claimed.

- ↑ Stefan Strötgen: "I compose the party congress ...". On the role of music in Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of Will . In: Annemarie Firme, Ramona Hocker (Ed.): From battle hymns and protest songs. On the cultural history of the relationship between music and war . Transcript, Bielefeld, pp. 139–157, here: pp. 153f.

- ↑ Werner Welzig : Space cooperative. Speech at the opening of the 10th International Germanist Congress . ( Memento from April 29, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) 10. – 16. September 2000, Vienna.

- ↑ Elke Fröhlich (ed.): The diaries of Joseph Goebbels . KG Saur, Munich. Part I. 1993-1996. Volume 9, p. 396.

- ↑ Oertel 1988, p. 110, which also quotes Goebbels' diary entry from June 30, 1937: "But it cannot be abolished."

- ↑ Oertel 1988, p. 169: “During the war, the cult around Wessel served to strengthen the population morally, as ... through its depiction of the“ fighting time ”this period, which ended with the victory of National Socialism over its opponents, was also alive should be. In this way one tried to give the impression that the situation of the war corresponds to the situation before 1933. "

- ↑ Act No. 154 of the American Military Government on “Elimination and Prohibition of Military Training”, Official Gazette of the Military Government of Germany, American Control Area, 1945, p. 52.

- ↑ Otto Köhler: Dresden Press Club desecrates Kästner . In: Ossietzky , 15/2004.

- ↑ a b c Quote from the report of the Schleswig-Holstein Public Prosecutor Eduard Nehm of March 28, 1961 to Bernhard Leverenz , at that time Minister of Justice of the State of Schleswig-Holstein. Jaager personnel file, in: PA Landesarchiv Schleswig-Holstein Department 786, No. 122 and 474; quoted according to: Klaus Godau-Schüttke: I only served the law. The "renazification" of the Schleswig-Holstein judiciary after 1945 , Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 1993, p. 116f.

- ↑ Broderick, p. 36.

- ^ Right-wing extremist subcultures . ( Memento from July 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 2.9 MB) Protection of the Constitution Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Anette Ramelsberger: Neo-Nazi Trial. The worst of all worlds . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , August 30, 2004.

- ↑ Correspondence on the national anthem from 1952 ( memento of August 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the Federal Ministry of the Interior.

- ↑ Ralph McKnight Giordano: ade East Prussia . 5th edition. dtv, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-423-30566-5 , p. 245 (hardcover published by Kiepenheuer and Witsch; Cologne 1994; ISBN = 3-462-02371-3).

- ↑ Article: Death in June Demystified ( Memento from February 22, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Herman Wouk: War and Remembrance . Little, Brown & Co., Boston 1981. Here: p. 981.

- ↑ Jost Müller-Neuhof, Sylvia Vogt: Horst-Wessel-Lied in music lessons. What can school do? In: Der Tagesspiegel , April 16, 2015. Online .

- ↑ Josef Rössler in Heinz Degle: tell Tyrolean witnesses - 1918-1945: Living history . Bolzano 2009, p. 135.

- ↑ Albrecht Dümling: Don't let yourself be seduced! Brecht and the music . Kindler, Munich 1985, p. 503f.

- ↑ Robert Gernhardt: Rhyme and time. Poems. Reclam, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-018619-0 , p. 167.