Lucius Vitellius (father)

Lucius Vitellius (* not later than 10 BC; † after 51 AD) was a Roman consul and censor . As governor of Syria, he was the coordinator of Roman policy on the Orient and one of the most influential senators under the emperors Caligula and Claudius , who honored him with the extraordinary honor of three consulates. He was valued by his contemporaries as a capable governor and despised as an eloquent courtier. His son Aulus Vitellius was in the Year of the Four Emperors 69 n. Chr. Roman Emperor .

Life

Origin and family

Lucius Vitellius came from the Vitellier family , who probably came from Luceria in Apulia . His father Publius is the first historically tangible member of this family, for whose origin the biographer Suetonius offers two possibilities: According to a Quintus Elogius, the Vitellians are descendants of the god Faunus and a Vitellia and were recognized as patricians in Rome . Cassius Severus , on the other hand, attribute the Vitellier to a freedman who earned his living as a shoe repairer. Both messages, however, must be considered speculative.

Publius Vitellius, Lucius 'father, worked as Augustus' caretaker and had a total of four sons: Aulus held the consulate together with Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus in 32 and was known as a bon vivant. Quintus reached the bursary under Augustus , but was expelled from the Senate under his successor Tiberius . The younger Publius had accompanied Germanicus on his journey to the Orient and in 20 was decisively involved as a prosecutor in the trial of the governor of the province of Syria , Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso , who committed suicide before the outcome. He later became a praetor . As a supporter of the scheming Praetorian prefect Sejan , he was arrested after his execution and attempted suicide, but eventually succumbed to illness.

The fourth son, Lucius, achieved the greatest political importance. Presumably through his admiration for the younger Antonia , Augustus ' granddaughter , he gained early access to the imperial family. With his wife Sextilia he had two sons, of whom Aulus , the future emperor, belonged to the youthful staff of the aging Tiberius on Capri . He was accused of promoting his father's career by allowing Tiberius to abuse him. His senatorial career must have been rather slow, however, as he was 34, the year of his first consulate, at least 44 years old and thus had already exceeded the traditional minimum age of 42 years.

Vitellius and the Parthians

Vitellius held the consulate of the year 34 together with Paullus Fabius , not as a suffect consul , but as a full consul at the beginning of the year, and in this function he was able to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Tiberius' reign on June 26th. A year later, when Parthian nobles complained to Tiberius about their King Artabanos II , the Emperor sent Phraates to Parthia as heir to the throne. However, Phraates, who was a son of King Phraates IV and had lived in Rome for many years, died on the trip. At the same time, Artabanos II brought his own candidate to the throne of Armenia after the death of the Roman vassal king Zenon , which was decidedly contrary to the interests of Rome in long-contested Armenia. In response, Tiberius sent Vitellius as imperial legate (legatus Augusti pro praetore) and Tiridates , another Parthian prince, to Syria in the role of aspirant to the throne. Whether Vitellius was also given extraordinary command over the east of the empire, as it appears with Tacitus, is debatable.

As governor of the important border province of Syria, Vitellius commanded four Roman legions , so he had more than 20,000 soldiers under his command. When he mobilized his troops and threatened to invade the Parthian Empire, Artabanos and his army, which had fought in Armenia against the Iberians under Mithridates, withdrew to the Parthian heartland. After this military failure, it was easy for Vitellius and his Parthian allies to turn the Parthian nobility against his king, who ultimately sought his salvation in flight. Now the way to the throne seemed clear for Tiridates. Vitellius accompanied him with his soldiers to the Euphrates , where the two tried to favor their gods by making a sacrifice . After another show of force - the Roman troops crossed the river on a ship bridge - Vitellius returned to Roman territory.

In the meantime, a Cilician tribe that refused to accept the Roman census and the associated tax payments had holed up in the Taurus Mountains . Vitellius commissioned Marcus Trebellius to put down the revolt. Trebellius marched with 4,000 legionnaires to Asia Minor, where he locked the rebels on two hills and forced them to surrender. Tiridates meanwhile received the recognition of the nobility and the cities of Parthia. He solemnly moved into the Parthian capital Seleukia-Ctesiphon , where he was crowned king with the diadem . His predecessor's treasure and harem also fell into his hands. However, he had not been able to win over some influential nobles to his side. They sought and found the deposed King Artabanos, who had retired to Hyrkania on the Caspian Sea , and tried to persuade him to return to the throne.

Artabanos did not take long to ask. He recruited Scythian troops and hastily moved with them to Seleukia-Ctesiphon. He initially kept the simple clothes he wore in exile in order to win the sympathy of the population. Tiridates was undecided whether he should face Artabanos or play for time. When he finally decided on a tactical retreat, the majority of his soldiers defected to his opponent, who now again took power in the Parthian Empire. Tiridates had to return to Vitellius defeated. In the early summer of 37, the Roman governor and Artabanos, who had returned to the throne, finally met on a bridge over the Euphrates. Artabanos recognized the Roman supremacy and granted the Romans sovereignty over Armenia. The Parthian Crisis of 35-37 ended with a Roman success, which for the ancient historian Karl Christ represents “one of the most astonishing foreign policy achievements of Tiberius” (who is known for his foreign policy inaction).

Vitellius in Palestine

As governor of Syria, Vitellius was also in charge of Judea , which, due to the structure of its upper class and the monotheistic faith of the Jews living there, had a tense relationship with Rome. Judea and the surrounding areas were 4 BC. Was divided among the sons of King Herod . The last surviving son of Herodes , the tetrarch Herodes Antipas , had a quarrel with Aretas IV , king of the Nabataeans . Herod had been married to a daughter of Aretas, but then left her for his relative Herodias . Border disputes finally led to a military conflict between the warring princes, in the course of which Herod suffered a crushing defeat. Herod complained in a letter to Emperor Tiberius, who was always favored by him. Thereupon Vitellius received the order from the emperor to carry out a retaliatory strike against Aretas. Because of differences with Herod Antipas, in whose resurgence Vitellius saw no advantage, he followed the imperial order only hesitantly and tried to drag out the preparations.

In addition, Vitellius had to deal with a lawsuit by the Samaritans in the winter of 36/37, accusing Pontius Pilate , the prefect of Judea known from the New Testament , of murdering Samaritan pilgrims. A man who claimed to know the cave in which the temple implements of Moses, which had been lost since the Babylonian exile (including above all the tent of meeting and the ark ) were hidden, had numerous Samaritans, including apparently armed men, march on the Mount Garizim moves. Pilate's soldiers had stopped them and, on his orders, on July 15, 36 caused a bloodbath among the pilgrims. Vitellius sent Pilate back to Italy, where he was to answer before the emperor. He entrusted his friend Marcellus with the administration of Judea .

Finally, at the beginning of March 37, Vitellius set two legions marching through Judea to support Herod Antipas and accompanied him to Jerusalem for the Passover festival to get an idea of the situation there. Whether Vitellius had visited Jerusalem a year earlier is debatable. In any case, in the previous year he had deposed the long-time Jewish high priest Kajaphas and replaced him with his brother-in-law Jonathan for reasons that were not entirely clear and which were obviously connected with the deposition of Pilate . After the residents of the city had received him kindly, he again granted the Jewish temple authorities the right to dispose of the sacred vestments that had been in Roman custody since the death of King Herod, and he also released Jerusalem from the fruit sales tax. In addition, he replaced the high priest Jonathan with his brother Theophilos , both sons of Annas , the head of an influential Jerusalem priestly family with whom the Roman authorities had cooperated for many years. On the fourth day of his stay, he received news of the death of his patron Tiberius and the accession of Caligula . Thereupon Vitellius withdrew his troops again, since he considered the campaign against the Nabataeans to be no longer necessary in this situation.

Return to Italy

After Caligula Publius had appointed Petronius to succeed Vitellius, he returned to Italy and, according to a testimony of the elder Pliny from Syria, introduced special fig varieties and the pistachio there. With the replacement, Caligula probably intended to take a more stringent course towards the Jews, since he commissioned Publius Petronius to transform the temple in Jerusalem into a center of the imperial cult . Vitellius's successes in the East are also likely to have made him suspicious of the suspicious new emperor. According to the later historian Cassius Dio (around 155–235), Caligula even wanted to sentence him to death, but refrained from doing so when Vitellius threw himself at his feet and tearfully promised him divine worship. The anecdotal biographer Suetonius also tells us that he was the first to be prepared to worship Caligula as a god. When the emperor once claimed to him that he was talking to the goddess of the moon , Vitellius is said to have excused his failure to recognize the goddess by saying that only gods could see each other. Caligula is said to have counted him among his closest friends after this exaggerated flattery.

After Caligula's murder, Vitellius quickly won the trust of the new emperor Claudius , at whose side he became consul for the second time in 43. When Claudius left Rome to personally preside over the completion of the conquest of Britain , he even left him in charge of government. Vitellius also belonged to the priestly college of the Arval Brothers and probably held the office of magister ("teacher") in this college. In 47 Vitellius was the first Roman since Agrippa , who was not himself emperor, to receive the extraordinary honor of a third consulate. When Claudius organized secular games in the same year - that ancient Etruscan 110th anniversary celebration that Augustus held in 17 BC. BC had revived to mark the beginning of a new era, and the time of which had been recalculated by Claudius - Vitellius is said to have often wished the emperor the opportunity to celebrate this festival.

Claudius is likely to have heard flattery rather than ridicule from this statement, at least the sons of Vitellius Lucius and Aulus, the future emperor, reached the consulate in 48. Vitellius himself held the office of censor together with the emperor in 48–49 , which no one had held for many years. Coins minted under his imperial son mention the triple consulate and the censor's office, some for the second year.

Helpers to two empresses

In the Senate, Vitellius belonged to the faction of the Emperor's wife Messalina . He was involved in the conviction of the two-time consular Valerius Asiaticus , whom Messalina wanted to get out of the way. Her motives were probably her interest in the magnificent gardens of Lucullus , which were in the possession of Asiaticus, and jealousy of his lover Poppaea Sabina , the mother of the later wife of Nero . Asiaticus was brought to justice with the help of Sosibius , the tutor of Messalina's son Britannicus . Asiaticus had to answer to the Emperor and Vitellius in their capacity as censors against the charges of high treason through bribery as well as adultery and sexual devotion.

Messalina, who was also present, left the room, as Asiaticus' defense speech had moved her to tears, but recommended Vitellius to convict the accused. He spoke of the long friendship between the two of them and the numerous merits that Asiaticus had earned. Against this background, it is only fair if he is allowed to choose his own way of death. Asiaticus complained that he would rather have fallen victim to the artistry of Tiberius or the wrath of Caligula than the betrayal of a woman and the shameless mouth of Vitellius, but had to submit to his fate and opened his veins. A little later, at Vitellius' instigation, Sosibius received a million sesterces as a reward for the good service he had rendered to the imperial family.

As a sign of his special admiration for Messalina, Vitellius is said to have even worn one of her shoes under his toga. He also counted Narcissus and Pallas , Claudius' most influential freedmen, among his household gods . Vitellius did not intervene in the execution of Messalina, who had remarried Gaius Silius in the absence of her husband Claudius , although Narcissus, who had informed the emperor, had seen him as a factor of uncertainty.

After her death, Vitellius quickly joined Agrippina , the new power in the imperial family. As the daughter of Germanicus, whose follower his brother Publius had once been, Agrippina was Claudius' niece. When the emperor wanted to marry Agrippina in 49, Vitellius convinced the Senate of the advantages of this union with a clever speech. He was able to persuade the other senators not only to advocate the marriage of Claudius, but also to generally allow the marriage of uncle and niece , which was previously regarded as incest . The possibility of such a connection was only banned again in 342, but apart from Claudius, only two cases in which it was used are documented.

In addition, Vitellius, as censor, deleted the incumbent praetor Lucius Junius Silanus from the Senate list, who was engaged to Claudius' daughter Octavia at the time . He accused him of incest with his sister Iunia Calvina , who was briefly married to the younger Lucius Vitellius. Junius Silanus then committed suicide and his sister was banished. Now Agrippina's son Nero Octavia could marry, which paved his way to emperor. The services Vitellius rendered to the new empress in establishing her position of power finally paid off. When he was accused of high treason by Junius Lupus in 51 , she arranged for Claudius to banish the accuser. Vitellius must have died soon after.

Antique rating

The historians Tacitus and Suetonius judge Vitellius largely in agreement: as provincial governor he was "capable", at least still "innocent" at the court of Caligula, but then fell into shameful servitude out of fear of the emperor, so that overall "his shameful old age forgot the good of his youth ”. Suetonius reports about the aging Vitellius, who “fell into disrepute because of his love for a freedman”, whose saliva he mixed with honey as a remedy on the carotid artery , both daily and in public. However, this procedure did not save him from dying from a stroke.

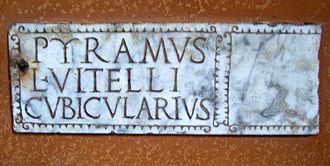

Vitellius was honored with a state funeral (funus censorium) and a statue on the forum bearing the inscription "Of a steadfast sense of duty to the emperor". In the year 69 his reputation with the army in the year of the four emperors contributed decisively to the elevation of his son to emperor by the Germanic troops. His successor as emperor, Vespasian , also seems to have benefited from his sponsorship in the 1940s. At the beginning of the second century, Tacitus said of Vitellius that "posterity will see him as a model of shameful flattery". It is believed that both Tacitus and Suetonius followed a tradition that tried to cast an unfavorable light on the members of Aulus Vitellius, who was the first emperor to carry out the death penalty.

swell

-

Cassius Dio : Roman History . Translated by Otto Veh . tape 4 (= books 51-60). Artemis & Winkler, Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-7608-3673-9 ( English translation by LacusCurtius ). For Lucius Vitellius the positions 59,27,2–6, 60,21,2, 60,29,1, 60,29,6 and 60,31,8 are relevant.

-

Josephus : Jewish antiquities . Translated by Heinrich Clementz. Marix, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-62-2 ( English translation ). In Josephus' work the passages 15,11,4, 18,4,2–5, 18,5,1, 18,5,3 and 18,8,2 deal with Lucius Vitellius.

-

Pliny : natural history . Edited and translated by Roderich König. Books 14–15. Artemis & Winkler, Zurich 1981, ISBN 3-7608-1594-4 . For Lucius Vitellius, 15.83 and 15.91 are relevant.

-

Suetonius : Vitellius . Translated by Adolf Stahr and Werner Krenkel . In: Life and Deeds of the Roman Emperors . Anaconda, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-86647-060-6 ( Latin text , English translation ). Most detailed antique biography from the collection of the emperor's biographies from Caesar to Domitian . The passages 2, 2, 2, 4–5 and 3 deal with Lucius Vitellius.

-

Tacitus : annals . Translated by Erich Heller. 5th edition. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf / Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-7608-1645-2 ( Latin text with English translation ). Books 6, 11 and 12 deal with the time when Lucius Vitellius was politically active. He is mentioned in 6.28, 6.32, 6.36–37, 6.41–43, 6.47, 11.2–4, 11.33–35, 12.4–6, 12.9, 12.42 and 14.56.

- Tacitus: Histories . Translated and edited by Helmuth Vretska . Reclam, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-15-002721-7 ( Latin text with English translation ). Lucius Vitellius is mentioned in 1.52 and 3.66.

literature

- Prosopographia Imperii Romani . 1st edition. V 500.

- Edward Dabrowa: The governors of Roman Syria from Augustus to Septimius Severus . Habelt, Bonn 1998, ISBN 3-7749-2828-2 , pp. 38-41 .

- Thomas A. Durey: Claudius and his advisors . In: The ancient world . tape 12 , 1966, pp. 144-155 , especially 144-147 .

- Werner Eck : L. Vitellius [II 3]. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 12/2, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01487-8 , Col. 261 f.

- Jens Herzer : Pilate between history and literature . In: Christfried Böttrich , Jens Herzer (ed.): Josephus and the New Testament. Reciprocal perceptions (= Scientific research on the New Testament . Volume 209 ). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149368-3 , p. 432-450 , especially 440, 442-444, 449 .

- Klaus-Stefan Krieger: Historiography as apologetics with Flavius Josephus . Francke, Tübingen u. a. 1994, ISBN 3-7720-1888-2 , pp. 48–59, 69–71 (also dissertation, University of Regensburg 1991).

- Theo Mayer-Maly : Vitellius 7c). In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplementary Volume IX, Stuttgart 1962, Sp. 1733-1739.

- Dennis Pausch : biography and culture of education. Representations of persons in Pliny the Younger, Gellius and Suetonius (= Millennium Studies . Volume 4 ). de Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-11-018247-5 , pp. 278–282, 317–319 (also dissertation, University of Gießen 2003/2004).

- Steven H. Rutledge: Imperial Inquisitions. Prosecutors and informants from Tiberius to Domitian . Routledge, London 2001, ISBN 0-415-23700-9 , pp. 284-288 .

Web links

- Jona Lendering: Lucius Vitellius . In: Livius.org (English)

- Coin image of Lucius Vitellius

Remarks

- ↑ Rome, CIL 06, 37786 = AE 1910, 00029 .

- ^ The text by Suetonius , Vitellius 1,3 and 2,2 contains Nuceria , that of Tacitus , Historien 3,86 against it Luceria . In his comments on Tacitus in Philologus , Volume 21, 1864, pp. 623-624, Friedrich Ritter mentions the corresponding passage in Tacitus as a later addition, but avoids choosing one of the two readings.

- ^ Suetonius, Vitellius 1 , 2–3 ; 2.1 .

- ↑ On Publius Vitellius and his sons Aulus and Quintus Suetonius, Vitellius 2,2 . At the time of the Quaestorship Vitellius 1,2 , for exclusion from the Senate also Tacitus, Annalen 2,48 .

- ↑ On the discovery of a bronze inscription and other sources on the Werner Eck / Antonio Caballos / Fernando Fernández trial, Das Senatus consultum de Cn. Pisone patre , Munich 1996.

- ^ To Publius Suetonius, Vitellius 2,3 . The Suetonius manuscripts have here C. [= Gaius] Piso , in Tiberius 52.3 contrast Cn. [= Gnaeus] Piso . Details on the career of Publius Vitellius in Tacitus, Annalen 1,70 ; 2.6 ; 2.74 ; 3.10; 3.13 ; 5.8 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 11,3,1 .

- ^ Suetonius, Vitellius 3.2 .

- ↑ Cf. Werner Eck, L. Vitellius , Col. 261 f.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6,28,1 ; Cassius Dio 58.24.1 . The ordinary consulate at CIL 10, 901 = Hermann Dessau , Inscriptiones Latinae selectae , No. 6396 is documented in writing.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6: 31-32 ; Cassius Dio 58.26.1-2 .

- ↑ Tacitus writes in Annals 6,32,2 cunctis, quae apud orientem parabantur, L. Vitellium praefecit , which can be understood as supervision of Armenia. Discussion in Theo Mayer-Maly, Vitellius , Sp. 1734.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6:36 ; Cassius Dio 58.26.3 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6:37 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6:41 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6.41 to 6.43 .

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 6.44 .

- ↑ Karl Christ, Geschichte der Roman Kaiserzeit , Munich 2002, p. 206 after Suetonius , Vitellius 2,4 , Josephus , Jüdische Altert leads 18,4,5 and Cassius Dio 59,27,3 .

- ↑ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18,5,1 . Rainer Metzner: The celebrities in the New Testament. A prosopographic commentary. Göttingen 2008. p. 34.

- ↑ Reinhold Mayer, Inken Rühle: Was Jesus the Messiah? History of the Messiahs of Israel in three millennia. Tübingen 1998. p. 54.

- ↑ Gerd Theißen: The historical Jesus. A textbook. 4th ed., Göttingen 2011. pp. 141f. Alexander Demandt: Pontius Pilate. Munich 2012, p. 62 f.

- ↑ Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 18,4,1–2 . Jens Herzer, Pilatus Between History and Literature , pp. 442–444; Klaus-Stefan Krieger, Historiography as Apologetics with Flavius Josephus , pp. 48–59, 69–71.

- ↑ Fergus Millar, The Roman Near East , Cambridge 1993, pp. 55–56, according to Josephus, assumes two visits. Concerns about the representation of Josephus in Mayer-Maly, Vitellius , Sp. 1735 with reference to Walter Otto , Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswwissenschaft (RE), Volume Suppl. II, Sp. 185 f.

- ^ Rainer Metzner: The celebrities in the New Testament. A prosopographic commentary. Göttingen 2008. P. 81 f.

- ↑ Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 15,11,4 ; 18.4.3 .

- ↑ Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18: 5 , 3 ; Philo , Embassy to Gaius 231 .

- ^ Rainer Metzner: The celebrities in the New Testament. A prosopographic commentary. Göttingen 2008. p. 34.

- ↑ CIL 6, 1968

- ↑ Josephus, Jüdische Antiquities 18,8,2 ; Philo, Embassy to Gaius 230–231 .

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia 15.83; 15.91 .

- ↑ Cassius Dio 59,27,4-6 ; Suetonius, Vitellius 2.5 . Steven H. Rutledge, Imperial Inquisitions , p. 104 assumes that Vitellius should have been convicted on the basis of an anonymous complaint. On Vitellius and Caligula cf. Aloys Winterling , Caligula , Munich 2007, pp. 139-140, 145, 150-151, 153-155, 179.

- ↑ a b c Suetonius, Vitellius 2,4 .

- ↑ CIL 6, 2032 , lines 1, 11, 20; CIL 6, 2035 = 32349, lines 5, 13.

- ^ Suetonius, Vitellius 2, 4–5 . In addition, Dennis Pausch, Biographie und Bildungskultur , pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annalen 14,56,1 ; Tacitus, Historien 1,52,4 ; 3.66.3 ; Plutarch , Galba 22.5 ; Cassius Dio 60.21.2 ; 60.29.1 ; Epitome de Caesaribus 8.1 .

- ^ Theo Mayer-Maly, Vitellius , Sp. 1734.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 11,2,1 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 11: 1-3 ; Cassius Dio 60.29.6 . On the proceedings against Valerius Asiaticus and Vitellius' role therein, Steven H. Rutledge, Imperial Inquisitions , pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 11,4,6 .

- ^ Suetonius, Vitellius 2.5 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 11: 33-35 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 12: 5-7 ; Cassius Dio 60,31,8 .

- ↑ Anthony A. Barrett, Agrippina. Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Empire , London 1999, p. 116.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 12: 3-4; 12.8 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 12:42 . On Iunius Lupus Steven H. Rutledge, Imperial Inquisitions , pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 6,32,5 .

- ↑ According to Suetonius, Vitellius 3.1 , the inscription was Pietatis immobilis erga principem .

- ↑ Tacitus, Histories 1,9,1 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Historien 3,66,3 .

- ↑ Tacitus, Annalen 6,32,5 : exemplar apud posteros adulatorii dedecoris habetur .

- ↑ See Brigitte Richter, Vitellius. A caricature of historiography , Frankfurt am Main 1992.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vitellius, Lucius |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Roman senator, father of the emperor Vitellius |

| DATE OF BIRTH | before 10 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 51 |