Hildebrand's song

The Hildebrandslied (Hl) is one of the earliest poetic testimonies in a German language from the 9th century . It is the only surviving text testimony to a Germanic type of hero song in German literature, and it is also the oldest surviving Germanic hero song. The traditional heroic epic allusion poem consists of 68 long verses. It tells in Old High German or Old Saxon (see below) an episode from the legends around Dietrich von Bern .

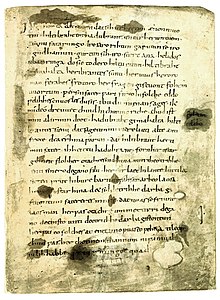

As the oldest and only work of its kind, the Hildebrandslied is a central object of Germanistic and medieval linguistics and literature. The anonymous text was given its current title by the first scientific editors Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm . The Codex Casselanus, which contains the Hildebrand's song, is in the manuscript collection of the State and Murhard Library in Kassel .

content

|

Old High German

Ik gihorta dat seggen, |

German

I heard (credibly) report Transmission: Horst Dieter Schlosser: Old High German Literature. Berlin 2004. |

Hildebrand left his wife and child and went into exile with Dietrich as a warrior and henchman. Now he is returning home after 30 years. A young warrior confronts him on the border between two armies. Hildebrand asks him who sin fater wari (who his father is). Hildebrand learns that this man, Hadubrand , is his own son. He reveals himself to Hadubrand and tries by offering gifts (golden bracelets) to turn to him as a family-father. Hadubrand, however, brusquely rejects the presents and says that he is a crafty old hun, because seafarers had told him that his father was dead ( dead is hiltibrant ). What is more, the advances of the stranger who pretends to be his father are for Hadubrand a bad abuse of the honor of his father, who was believed dead. If the mockery of the "old hun" and the rejection of the presents are a challenge to the fight, then Hildebrand, according to Hadubrand's words, that his father is a man of honor and bravery in contrast to the unfamiliar counterpart, is no longer open to Hildebrand. According to custom, he is now compelled to accept the challenge of his son to fight for the sake of his own honor - at the risk of his own death or that of his son. Experienced in the world and in battle, Hildebrand anticipates the things that will follow and complains about his terrible fate: “welaga nu, waltant got”, quad Hiltibrant, “wewurt skihit” (“Woe, ruling God,” said Hildebrand, “a bad fate takes its course! ”) Between two armies, father and son stand opposite one another; the inevitable fight ensues. Here the text breaks off. Presumably, as a later Norse text indicates, the battle ends with the death of Hadubrand.

reception

Handwriting description

The only surviving text witness to the Hildebrand's song is stored in the Kassel University Library under the shelf mark 2 ° Ms. theol. 54 kept. The manuscript is one of the library's old holdings. After 1945, the manuscript was temporarily in the USA as spoils of war , where criminal antiquarians separated the two sheets and sold one of them for a large sum. It could not be reunited with the Codex until 1972. The text of the Hildebrand song is on pages 1 r and 76 v of an early medieval parchment -Handschrift, so on the front of the sheet 1 and the back of the sheet 76. In these pages is it is originally left empty outer sides of the Code .

The main part of the codex was probably written around 830 in the Fulda monastery and contains the apocryphal texts Sapientia Salomonis and Jesus Sirach in Latin. The Old High German Hildebrand Song is obviously a subsequent entry from around the 3rd to 4th decade of the 9th century. The recording probably breaks off because there was not enough space on the last sheet.

Writing and language

Due to the plot in the spectrum of the Dietrich sagas, the Hildebrandslied is a so-called scion saga, which requires prior knowledge from the reader. From the legends surrounding Dietrich von Bern, the Hildebrand legend with the duel as a basic fable is one of the most important.

The Hildebrandslied was recorded around 830-840 by two unknown Fulda monks in mainly Old High German, but in a peculiar Old Saxon - Old Bavarian mixed form and with Anglo-Saxon writing peculiarities . From the typeface of the text it can be seen that the first scribe's hand is responsible for verses 1–29 and the second scribe's hand for verses 30–41. The Anglo-Saxon or Old English influences become clear, for example, in verse 9, in the phrase: ƿer ſin fater ƿarı , as well as through the use of the old English character ƿ for the uu sound, as well as in the ligature “æ”, for example in verse 1.

The attempt to explain the mixture of High and Low German dialect is that the Low German writer (s) were probably only able to render the High German song inappropriately. These transcription errors indicate that the clerks were probably working according to the original. To this fact come Old High German lexemes, which can only be found in the Hildebrandslied ( Hapax legomenon ), such as the conspicuous compound sunufatarungo (verse 3), the exact meaning of which is unclear and is scientifically discussed.

"The initial tenues in prut (» bride, wife «) or pist (» bist «) or the initial affricates in chind (» child «) etc. are clearly Upper German . Low German is the consistently unshifted t in to (» to «), uuêt ("white"), luttila ("lützel, small") or the nasal shrinkage in front of dentals e.g. B. in ûsere ("our") or ôdre ("other"). The evidence that a top German document was inked in Low German, is located in the hyper-correct forms before as urhettun - Old High German urheizzo ( "Challenger") or huitte - Old High German hwizze ( "white"). Here the written double consonants tt do not correspond to the Low German phonetic level, but are explained as a mechanical implementation of the correct Upper German Geminat zz , to which simple t in Low German would correspond. "

To illustrate the mixed-language coloring, Georg Baesecke contrasted the traditional text with a purely Old High German translation, exemplarily verses 1–3 (corrections of spelling errors in italics):

- I h gihorta da z say

- da z urhi zz un einon muozin,

- Hiltibra n t enti Hadubrant untar heriun z ueim.

The origin of the original Hildebrand's song is set in northern Italy , since the Gothic language does not have a name ending in "-brand", which is documented in Langobard . The Hildebrand song probably came from the Lombards to Bavaria in the second half of the 8th century (770–780) and from there to Fulda . Helmut de Boor summarized the way of the tradition and concluded that an Old Bavarian Germanization was carried out on the basis of an original Gothic-Longobard script. After the takeover in Fulda, the old Saxon coloring followed, followed by the last entry handed down today.

construction

The structure of the song is simple and clear and consciously artistically composed through the use of old epic forms and uses special stylistic devices. The opening of the introductory plot in verse 1 Ik gihorta dat seggen is an example of the ancient epic forms . This form can be found in parallel in other Germanic literatures and in the Old High German context in the opening of the Wessobrunn prayer in the manner: Dat gafregin ih with firahim .. , “I asked the people about that”. Design elements can also be recognized as they are common in the rest of Germanic heroic poetry, for example in the Abvers (66) through the form huitte scilti as a shining or shining shield in the concrete duel situation . Furthermore in the form gurtun sih iro suert ana (verse 5) comparing with verses 13-14 of the old English Hengestlied , here gyrde eing his swurde . The special stylistic devices are, on the one hand, pauses and, on the other hand, the alliteration in prosody. The verse metric is exemplified and ideally shown in the phrase of the third verse:

" H iltibrant enti H adubrant untar h eriun tuem "

However, the use of prose lines (verses 33–35a) and end rhyme ties mean that the rules of alliteration are often not taken into account. There are also disturbances in the initial and in some abbreviations double bars (V.18 heittu hadubrant ), as well as double bar rhymes in the form »abab«. Furthermore, the prosody, analogous to the old Saxon Heliand , which also comes from the Fulda continuum , has the hook style , a takeover of the staff initials in the accentuation of the following anverses. The structure of the song can be shown schematically as follows:

- Introductory act

- First dialogue sequence

- Action, briefly to the middle of the text (verses 33-35a)

- Second dialogue sequence

- Final action, duel

The internal structure of the dialogue part is evaluated differently in older research, contrary to the overall structure of the text, and is controversial. This has led to editions that differ from one another; especially by assuming that verses 10f., 28f., 32, 38, 46 are incomplete. Therefore the wording was partly edited and the verse sequence modified. More recent research is more conservative with the corpus and attaches a conscious artistic form to the traditional version. Only verses 46–48 are ascribed to Hadubrand by the majority of researchers today; placement after verse 57 is advocated. In the following table, text-critical interventions are compared using the editions by Steinmeyer, Baesecke and De Boor:

| Steinmeyer | Baesecke | De Boor |

|---|---|---|

| Hild. 11-13 | Hild. 11-13 | Hild. 11-13 |

| Had. 15-29 | Had. 15-29 | Had. 15-29 |

| Hild. 30 - 32 + 35b | Hild. 30 - 32 + 35b | Hild. 30-32 |

| Had. 37-44 | Had. 37-44 | Had. 46-48 |

| Hild. 49-57 | Hild. 46-48 | Hild. 35b |

| Had. 46-48 | Had. is missing | Had. 37-44 |

| Hild. 58-62 | Hild. 49-57 | Hild. 49-62 |

| Had. is missing | ||

| Hild. 58-62 |

Historical background

In terms of time, the plot should be classified in the 5th century ( hero age ). The people mentioned in the text serve as a reference for this: Odoacer ( Otacher verse 18, 25), who fought against the Ostrogoth king Theodoric the Great ( Theotrich verse 19, Detrich verse 23, Deotrich verse 26). In verse 35 the lord (henchman) of the Huns is called Huneo truhtin ; presumably this is Attila . Odoacer was a Teuton from the Skiren tribe and had deposed the last Western Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus in 476 ; then his troops proclaimed him King of Italy ( rex Italiae ). In the Germanic heroic saga, Theoderic, based on the short, episodic song forms, was handed down to Dietrich von Bern ( Verona ) of today's epic. Attila later became the Etzel / Atli from the German and Nordic Nibelungen context . Behind the figure of Hildebrand, older researchers (Müllenhof, Heusler) saw the historical, Ostrogothic military leader Gensimund . As early as the early 20th century, Rudolf Much referred to Ibba or Hibba , who operated successfully as Theodoric's military with contemporary historiographers such as Jordanes .

According to Much and other researchers after him, Ibba was assumed to be a short form or nickname of Hildebrand, with the hint that "Ibba" - like the ending "-brand" - could not be traced in Gothic. The passages of the song regarding Hildebrand's absence for decades from his wife and child with Theodoric's flight (Ibba / Hildebrand in the wake) would find their historical reason in the battle of ravens , on the other hand Ibba / Hildebrand, due to the name, presumably of Franconian origin, as a follower of Theodoric, who through loyalty has earned a high rank in the Ostrogoth political-military nomenclature. Comparative historical evidence shows that the duel between the two armies arose out of the confused political situation in which such confrontations between close relatives occurred. These experiences were reflected in the song as part of the Longobard original form.

Enough

Since the end of the plot has not been handed down, it cannot be said with absolute certainty whether the ending was tragic. One can assume, however, because the text aims in its dramaturgical composition at the climax of the duel. The tragedy of the plot comes to a head through the psychological structuring of the exchange of words between father and son, through Hildebrand's conflict between the father's attempt at affection and rapprochement and the maintenance of his honor and self-evident position as a warrior. The so-called "Hildebrand's Death Song" in the Old Norse Fornaldarsaga Ásmundar saga kappabana from the 13th century is evidence of this . The Death Song is a fragmentary song in the Eddic style within the prose text of the saga. In six incomplete stanzas, especially the fourth, Hildibrand retrospectively laments the struggle with the son and his tragic death:

|

“Liggr þar inn svási at hǫfði, |

There lies at my head, the only heir that became |

Basic text: Gustav Neckel, Hans Kuhn 1983. Transfer: Felix Genzmer, 1985.

In the German Younger Hildebrandslied , the father also wins, but the two recognize each other in time. This text is clearly influenced by the High Middle Ages, because the duel shows the nature of a knightly tournament, that is, it has the characteristics of a quasi sporting competition. A later variant (only preserved in manuscripts between the 15th and 17th centuries in Germany) offers a conciliatory variant: in the middle of the fight, the arguing turn away from each other, the son recognizes the father, and they embrace. This version ends with a kiss from the father on the forehead of the son and the words: “Thank God, we are both healthy.” As early as the 13th century, this conciliatory variant reached Scandinavia from Germany and was incorporated into the Thidrek saga (oldest preserved manuscript as early as 1280), a thematic translation of German sagas from the circle around Dietrich von Bern. In the Thidrek saga, the outcome of the fight is portrayed in such a way that after father and son have recognized each other, both return to their mother and wife with joy. Overall, in comparison with the later interpolations, the tragedy is greater and more in line with the Germanic-contemporary feeling when the father kills his son. He thus deletes his family or genealogy.

"This individually shaped fable is present in three non- Germanic legends: the Irish one from Cuchullin and Conlaoch, the Russian one from Ilya and Sbuta Sokolniek, the Persian one from Rostam and Sohrab."

Because of the similarity in content, this tragedy is often compared with the story of Rostam and Sohrab from the Shahnameh , the Iranian national epic of Firdausi , written in the 10th century . In this, with more than 50,000 verses, the most extensive epic in world literature, the fight between his father Rostam and his son Sohrab is reported. Rostam, who left his wife before his son was born, left her his bracelet, which she should give to Rostam's daughter or son as a sign of identification. Sohrab, who has just come of age in search of his father, is involved in a duel with his father with a fatal outcome. Rostam discovers the bracelet on the dying man and realizes that he has killed his own son. Friedrich Rückert made this part of the Shāhnāme, which is one of the highlights of the epic, known in the German-speaking world with his adaptation Rostem und Suhrab, published in 1838 . While at Firdausi the father stabbed his son, kills in Oedipus Tyrannus of Sophocles son of his father Laius. The various parallels can be explained, on the one hand, by an Indo-European legend on which the poetic designs were based; on the other hand, a direct influence can be assumed in some cases. The Germanist Hermann Schneider assumed the motif from a traveling legend or world novella . Ultimately, an explanation is possible through universally effective archetypes that can be traced back to basic psychological and social structures, such as those examined by Carl Gustav Jung , Karl Kerényi , Claude Lévi-Strauss and Kurt Hübner , among others . The Brothers Grimm name the text in their comment on the fairy tale The Faithful John and the Schwank The old Hildebrand with regard to the possible infidelity of the wife who stayed at home.

Reception in 19th century poetry

The so-called Hildebrandsstrophe was named after the stanza form of the Hildebrandslied . B. was extremely popular with Heinrich Heine or Joseph von Eichendorff . Since this stanza form is, unlike the original, a four-verse version, it is also referred to as half Hildebrand's stanza. A famous example of a representative of this stanza form is Eichendorff's poem Mondnacht .

Others

The GDR rock band Transit processed the subject in 1980 in their "Hildebrandslied", and the Pagan Metal band Menhir released an album of the same name in 2007 on which the Old High German original text was sung.

literature

facsimile

- Wilhelm Grimm : De Hildebrando, antiquissimi carminis teutonici fragmentum . Dieterich, Göttingen 1830 ( archive.org [accessed January 20, 2018]). (first facsimile)

- Eduard Sievers : The Hildebrandslied, the Merseburger Zaubersprüche and the Franconian baptismal vows with photographic facsimile based on the manuscripts . Orphanage bookstore, Halle 1872 ( google.com [accessed January 20, 2018]). (first photographic facsimile)

- Hanns Fischer : Tablets for the Old High German reading book . Tübingen 1966, ISBN 3-484-10008-7 .

- President of the University of Kassel (ed.): Das Hildebrandlied - Facsimile of the Kassel manuscript with an introduction by Hartmut Broszinski . 3. revised Edition. kassel university press, Kassel 2004, ISBN 3-89958-008-7 .

Editions and translations

- Georg Baesecke : Hildebrand song . (incl. facsimile), Niemeyer, Halle an der Saale 1945.

- Wilhelm Braune , Ernst A. Ebbinghaus : Old High German Reading Book , 17th edition, Tübingen 1994, ISBN 3-484-10708-1

- Johann Georg von Eckhart : Commentariis de rebus Franciae orientalis . tape I . University of Würzburg, Würzburg 1729, XIII Fragmentum Fabulae Romanticae, Saxonica dialecto seculo VIII conscriptae, ex codice Casselano, S. 864-902 ( google.co.uk [accessed December 28, 2017]). ( Editio princeps )

- Wolfram Euler : The West Germanic - from its formation in the 3rd to its breakdown in the 7th century - analysis and reconstruction. Verlag Inspiration Un Limited, London / Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8 . (Longobard version of the Hildebrandslied on pp. 213–215.)

- The Brothers Grimm : The two oldest German poems from the eighth century: The song of Hildebrand and the Weissenbrunner prayer presented and published for the first time in their meter . Thurneisen, Kassel 1812 ( archive.org [accessed January 20, 2018]). (The first scientific edition.)

- Siegfried Gutenbrunner : From Hildebrand and Hadubrand. Lied, Sage, Mythos , Heidelberg 1976, ISBN 3-8253-2362-5

- Walter Haug u. Benedikt Konrad Vollmann (Ed.): Library of the Middle Ages. Volume 1. Early German and Latin Literature in Germany 800–1150 , Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-618-66015-4

- Willy Krogmann : The Hildebrand's song produced in the original Lombard version. Berlin 1959.

- Horst Dieter Schlosser : Old High German Literature , 2nd edition, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-503-07903-3

- Elias von Steinmeyer : The smaller Old High German language monuments , Berlin 1916 ( digitized version of the ULBD )

- Old high German poetic texts. Old High German / New High German , selected, translated and commented by Karl A. Wipf (= Reclams Universal Library Volume 8709), Stuttgart 1992, ISBN 3-15-008709-0 .

Bibliographies, lexical treatises and individual aspects

- Helmut de Boor : The German literature from Charlemagne to the beginning of courtly poetry . In: History of German Literature Volume 1. CH Beck, Munich 1979.

- Klaus Düwel : Hildebrand's song . In: Kurt Ruh et al. (Ed.): Author's lexicon . The German literature of the Middle Ages . Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008778-2 .

- Klaus Düwel, Nikolaus Ruge: Hildebrandslied. In: Rolf Bergmann (Ed.): Old High German and Old Saxon Literature. de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-024549-3 , pp. 171-183.

- Elvira Glaser, Ludwig Rübekeil: Hildebrand and Hildebrandslied. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 14, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999, ISBN 3-11-016423-X , pp. 554-561. (introductory article)

- Wolfgang Haubrichs : History of German literature from the beginning to the beginning of the modern age . Vol. 1: From the beginnings to the high Middle Ages . Part 1: The Beginnings. Attempts at vernacular writing in the early Middle Ages (approx. 700-1050 / 60) . Athenaeum, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-610-08911-3 .

- Dieter Kartschoke: History of German Literature in the Early Middle Ages . DTV, Munich 1987.

- Helmich van der Kolk: The Hildebrandslied . Amsterdam 1967.

- Rosemarie Lühr: Studies on the language of the Hildebrand song. Regensburg Contributions to German Linguistics and Literature Studies, Series B: Investigations, 22. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Bern 1982, ISBN 3-8204-7157-X .

- Oskar Mitis: The characters of the Hildebrand song. In: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings 72nd year 1953/54, p. 31–38 ( digitized version )

- Robert Nedoma : Þetta slagh mun þier kient hafa þin kona enn æigi þinn fader - Hildibrand and Hildebrand saga in the Þiðreks saga af Bern. Francia et Germania. Studies in Strengleikar and Þiðreks saga af Bern, ed. By Karl G. Johansson, Rune Flaten. Bibliotheca Nordica November 5, Oslo 2012, pp. 105-141, ISBN 978-82-7099-714-5 .

- Opritsa Popa: Bibliophiles and Bibliothieves: The Search for the Hildebrandslied and the Willehalm Codex , Cultural Property Studies, De Gruyter 2003

- Meinolf Schumacher : Word battle of the generations. On the dialogue between father and son in the 'Hildebrandslied' . In: Eva Neuland (Hrsg.): Youth language - youth literature - youth culture. Interdisciplinary contributions to language-cultural forms of expression in young people . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-631-39739-9 , pp. 183-190 ( digitized version from Bielefeld University) .

- Klaus von See : Germanic heroic legend. Substances, problems, methods . Athenaeum, Wiesbaden 1971 (reprint 1981), ISBN 3-7997-7032-1 .

- Rudolf Simek , Hermann Pálsson : Lexicon of old Norse literature. The medieval literature of Norway and Iceland (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 490). 2nd, significantly increased and revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-520-49002-5 .

- Jan de Vries : Hero song and legend . Franke, Bern / Munich 1961, ISBN 3-317-00628-5 .

- Konrad Wiedemann: Manuscripta Theologica. The manuscripts in folio. In: The manuscripts of the Kassel University Library - State Library and Murhard Library of the City of Kassel. Volume 1.1. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 978-3-447-03355-8 .

Web links

- Digital copies of the University Library Kassel: Sheet 1 (1 r) , Sheet 2 (76 v)

- Text edition: Braune / Ebbinghaus reading book

- Text edition: Horst Dieter Schlosser

- Reading of the Hildebrandslied by Jost Trier as part of a lecture in the summer semester of 1965 (Baeseckes purely ahd. Transmission)

- Reading of the Hildebrandslied in Old High German and reconstructed Longobard language (with subtitles)

- Read the Hildebrandslied

- Private website (www.hiltibrant.de) with facsimile, text and translation

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hellmut Rosenfeld: Retainer Elder . In: German quarterly journal for literature and humanities, No. 26, p. 428 f.

- ↑ For details on loss and rediscovery: Opritsa D. Popa: Bibliophiles and Bibliothieves. The search for the Hildebrandslied and the Willehalm Codex . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003. (Cultural Property Studies.)

- ↑ Düwel: Col. 1245

- ↑ Uecker: p. 60 f. Düwel: Col. 1243

- ↑ RGA: p. 558 Proportionally lower proportions of Old Saxon morphemes to the essentially dominant Old High German lexic (vocabulary).

- ↑ Haubrichs: p. 153. RGA: p. 558

- ↑ de Boor: p. 67.

- ^ Ward Parks: The traditional narrator and the "I heard" formulas in Old English poetry . In: Anglo-Saxon England 16, 1987, p. 45 ff.

- ↑ Ulrike Sprenger: The Old Norse Heroic Elegy . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1992, p. 114

- ^ Theodore Andersson: The Oral-Formulaic Poetry in Germanic . In: Heldensage and hero poetry in the Germanic Heinrich Beck (ed.). de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1988, p. 7

- ↑ Düwel: Col. 1241

- ↑ Werner Schröder: "Georg Baesecke and the Hildebrandslied". In: Early writings on the oldest German literature . Steiner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-515-07426-0 , p. 24 ff.

- ↑ Werner Schröder: aoO p. 26 f.

- ↑ Basis: Basic text based on Braune-Ebbinghaus reader

- ^ Hermann Reichert: Lexicon of old Germanic personal names . Böhlau, Vienna 1987, p. 835.

- ↑ This is why the stanzas were included in modern editions of the Codex Regius and its individual language translations under this title.

- ^ Simek, Palsson: pp. 22, 166.

- ^ Friedrich Rückert: Rostem and Suhrab. A hero story in 12 books. Reprint of the first edition. Berlin (epubli) 2010. ISBN 978-3-86931-571-3 . (Details)

- ↑ de Vries: p. 68 ff.

- ↑ Burkhard Mönnighoff: Basic course poetry. Klett, Stuttgart 2010, p. 47.