Mimir

Mimir is a being from Norse mythology who guards one of the sources under the world tree Yggdrasil . Mimir's knowledge, wisdom, and prophecy are so famous that even Odin maintains a close bond with him for advice.

swell

Edda

The myths about Mimir come from various sources in Old Norse literature, but they are essentially contained in the oldest text of the Song Edda , the Völuspá , whose roots go back to pre-Christian times.

Then the source of wisdom rises under the world tree Yggdrasil. It is one of the three original sources in Norse mythology. Nearby is the Gjallarhorn of the god Heimdall , which sounds in all worlds when you blow into it. The keeper of the spring is Mimir, which is named after him Mimir's well . Every morning he drinks mead from her.

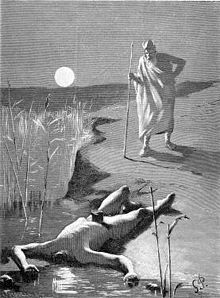

Odin gains wisdom because he also drinks from Mimir's well. However, he must first sacrifice an eye for it and put it in the well ( Walfather's pledge). Since then, Odin has been one-eyed. Despite his drink of wisdom, Odin turns to Mimir's head for advice when the order of the world is in danger and the gods are threatened with doom (the Ragnarök ). However, the Völuspá does not describe how it came about that Mimir was beheaded.

In Gylfaginning, Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda repeats and supplements the statements of the Völuspá. He says that the source is under the root of Yggdrasil, which goes to the frost giants . Mimir, like Odin, gains his knowledge and wisdom because he drinks from the spring. The Gjallarhorn serves as a drinking horn for him. On one point, however, Snorri differs significantly from the Völuspá. With him in the time of Ragnarok Odin rides to Mimir's well and gets Mimir's advice there. Mimir's head, however, does not mention Snorri.

Hrafnagaldr Óðins (Odin's Raven Magic), which is also one of the old Nordic songs, but is not part of the Song Edda, assumes, in contrast to the Prose Edda, that Mimir Odin cannot give advice so that he escapes his fate and the Avert the downfall of the gods.

“Nowhere is the sun or the earth stuck, the currents of air sway and plunge. In Mimir's clear source, the wisdom of men dries up. Do you know what that means? "

The song Sigrdrífumál , which is one of the heroic songs of the Song Edda, shows that the head of Mimir was not only wise, but also knew the runes . There Odin stands with Mimir's head on a mountain, but it is not Odin who speaks, but Mimir says "cleverly the first word and called true runes."

The Völuspá also speaks of Mimir's sons without specifying them.

Ynglinga saga

The Ynglinga saga , Snorri Sturluson mythical introduction to his story of the Norwegian kingship ( Heimskringla ), is not just the proximity of Odin to Mimir one, but also tells a story of how Mimir's main lost the fuselage: After the war, the Asengötter against Wanengötter make the ensir Mimir and Hönir as hostages as pledge of peace. The sir say of Hönir that he is a good leader. However, the Vanes soon notice that Hönir will not make a decision without his advisor Mimir. They therefore behead the wise man and send his head back to the sir. Odin then conserves the head with spells and herbs in order to continue to receive prophecies and messages from the other worlds. Mimir's gifts are so important to him that he always carries his head with him.

Þulur

The Þulur mention the name Mimir under the epithets of the giants.

research

The inhomogeneous and sometimes contradicting literary sources led to very different positions in research on how Mimir and his myths are to be understood. Not all of the questions raised have been answered satisfactorily to this day.

etymology

In the interpretation of the name Mimir, Old Norse Mímir , research is divided into two camps.

In one opinion, Mimir is closely related to wisdom and memory and means something like 'he who remembers'. The name is therefore related to Old English mimorian , Dutch mijmeren 'sinnen , be lost in thoughts', Latin memor ' mindful, remembering' and is traced back to the Indo-European word root * smer-, * mer- 'commemorate, remember'.

For the other opinion, the name is related to Norwegian meima 'measure', Anglo-Saxon māmrian 'brooding' and is derived from Indo-European * mer- 'measure' with the meaning 'measuring, thinking' or 'the one who measures fate'.

Nature and parentage

Mimir's nature cannot be determined with certainty. He is either a giant ( Thurse ) or a deity. Only the ulur express themselves about its nature . There Mimir's name is listed under the nicknames of the giants. However, the Ynglinga saga gives him the same position as the god Hönir , so that it is also argued that Mimir is like Loki himself a deity. However, the same rank does not necessarily lead to the same nature. Otherwise he or his name appears consistently gigantic in Norse literature. This includes several compound personal names with Mimir as the basic word, which clearly designate giants, for example Sokkmimir (an otherwise unknown giant) or Brekkmimir (epithet of the giant Geirröd ).

Tradition is silent about his origin. He could be the son of the ancient giant Bölthorn , who is the father of Odin's mother Bestla . Mimir would therefore be Odin's uncle . This view is based on a passage in the Hávamál in which Odin introduces his magic rune songs:

"I learn nine powerful songs from the famous son of Bölthorn, Bestla's father, [...]"

The son of Bölthorn is not otherwise mentioned in Nordic mythology. Mimir speaks for his wisdom, which Odin sought again and again, and his magic rune science, which requires secret and hidden knowledge. Ultimately, the relationship with Odin remains pure speculation.

Mimir's fountain and the world tree

Although the Völuspá says that Mimir drinks mead from his well, most research assumes that the well contains Mimir's water. But mead is not just a mere intoxicant, but also a wisdom potion that allows one to acquire special knowledge, as the myth of the theft of the poet's met by Odin suggests. The song Grimnismál says of the goat Heidrun am Baum Lärad , who is equated with the world tree Yggdrasil , that she donates mead to the Einherjern consecrated to Odin . Even if this mythical image comes from a comparatively late period, it at least points to a connection between the world tree, at the foot of which lies Mimir's fountain, father of gods and intoxicating potion.

The proximity between Mimir and the World Tree is not only evident in Norse mythology through Mimir's source. Research assumes that the name Mimirs was also used to describe the world tree. It is generally accepted that the tree Mimameidr 'Tree of Mimi' corresponds to Yggdrasil. Some researchers also represent this equation for the phrase in holti Hoddmímis 'in the forest of Goldmimir', which means the wood in which the two people hide, who, together with surviving sons of gods after the Ragnarök, will participate in a new world age .

The source on the World Tree belongs to the mythical landscape of many peoples. In addition to Mimir's well, the wells of the Urd and Hvergelmir also arise in Norse mythology under Yggdrasil . In the (Indo-European) origin, at least the wells of Mimir and the Urd were probably the same source, which was given different names due to different myths. Both Mimir and Urd are related to fate and prophecy.

Walfather's pledge

The myth of Walfather's pawn explains in a mythical image how Odin gains inner vision through the loss of an eye that enables him to see outwardly, the gift of clairvoyance or prophecy. The motif of self-sacrifice for wisdom can be found again in Odin. For nine nights he hangs on Yggdrasil in order to gain the secret knowledge of the runes through agony .

Mimir's head

The tradition about Mimir's head is still largely unexplained. The most important point of contention in the research is the question of whether the myths of Walfather's pawn and Mimir's head refer to one and the same person. The Nordic texts differ in the name spelling for both myths. If there is talk of Walfather's pledge, Mímir is written. When it comes to Mimirs head, it always says "Míms hǫfuð", so here actually Mimr without a second "i". In the Nordic texts even a third form of the name Mimirs can be deduced from the tree name Mimameidr, there it says: Tree of Mimi without a final "r".

These differences are exacerbated by the traditional content. After the Völuspá , Odin speaks to Mimr's head at the beginning of the Ragnarök, which according to the Ynglinga saga and the Sigrdrífumál he always carries with him. The Prose Edda, on the other hand, has Odin ride to Mimir's well to find Mimir. Apparently it assumes that Mimir has not been beheaded. Snorri Sturluson completes the confusion, since the Prose Edda and the Ynglinga saga contradict each other in terms of content, although they both come from his hand.

Numerous suggestions have been made to reconcile both myths. In part, two different mythical figures were assumed ( Jan de Vries ). Ultimately, however, the different narratives cannot be reconciled, nor are they about two different characters. Both myths have Indo-European parallels, which ultimately indicate that the two myths belong together . Tales of prophetic heads can be found in Greek (for example in the Orpheus myth) and Celtic myths as well as in Icelandic sagas . The myth of the Whale Father's pledge finds a counterpart in Norse mythology with regard to the voluntary abandonment of a body part when the god Tyr voluntarily gives up his right hand. There is also a parallel in the Roman legends about Horatius Cocles and Mucius Scaevola . The explanation of the Ynglinga saga, how Odin came to Mimir's head, remains incomprehensible . Research has not yet decided whether it is merely a mythographic attempt at explanation from later times, which may only reflect Snorri Sturluson's own interpretation.

In some cases it was even argued that the myth of the speaking skull was borrowed from Celtic mythology. But since it is a motif both in Icelandic sagas and in Norwegian and English sagas, it seems to be an independent Nordic or Germanic tradition. These Norwegian and English variants are perhaps the key to realizing what the main has to do with the source. They preserve a mythical motif in which a skull rises from a spring, bringing happiness and gifts to those who do him honor.

Natural mythological interpretations

Older research saw myths as early attempts by humans to explain the phenomena they observed in nature. In the natural mythological interpretation, the pair Odin and Mimir corresponded to the sky lights sun and moon. If the sun is in the sky, then it is reflected in the water, so that it seems that there is a second sun in the water, namely the eye that Odin gave as a pledge. Since it was previously assumed that the word moon comes from the Indo-European word root * mer- 'measure', the same root from which some researchers derive the name Mimir, it was obvious to assign Mimir (especially his head) as the mythical equivalent of the moon understand. Furthermore, from a mythical point of view, there was no difference between Mimir's source and his head, since the source was interpreted as his head. Mimir's sons were the rivers that flow from the spring.

Many of these natural mythological interpretations have now been abandoned. Mond and Mimir do not come from the same Indo-European word root. Accordingly, the moon does not mean “the one who measures”, but “the wanderer”. Mimir's head is also not Mimir's source, since the idea of the prophetic, decapitated skull is very old and has many equivalents in Greece, in the Celtic world and in Siberian shamanism .

interpretation

The world tree is a mythical image for creation as a whole. In it, Mimir's well stands at the root for access to deeper insight into the nine Germanic worlds: the memory of what has happened since the beginning of creation, and the view of what still has to happen (fate). That is the source of wisdom.

Their guardian is Mimir, who may appear in the shape of a skull to those who come to its source (myth of Mimir's head). Knowledge is acquired by those who make friends with the giant and how he drinks from the spring. But everyone but the wise man has to make a delicate sacrifice for it. If you want more insight, you have to use one of your eyes for it (myth of whale father's pledge).

literature

- Hilda Roderick Ellis Davidson: Pagan Europe - Early Scandinavian and Celtic Religions. Manchester University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-7190-2579-6 . (on-line)

- René LM Derolez: De Godsdienst der Teutons. 1959. (German: Götter und Mythen der Germanen. Translated by Julie von Wattenwyl. Verlag Suchier & Englisch, 1974)

- Francois Xaver Dillmann: Mimir. In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde . Volume 20, De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-017163-5 , p. 38 ff.

- Rudolf Simek : Lexicon of Germanic Mythology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 368). 3rd, completely revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-520-36803-X .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Simek 2006, p. 280 ff.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 27 f., 46 (citation of the Lieder-Edda after Arnulf Krause: Die Götter- und Heldenlieder der Älteren Edda. Reclam, 2004, ISBN 3-15-050047-8 ). [= Translation after Karl Joseph Simrock : The Edda . 1851, Wöluspa 21 f., 31, 47]

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 28 [= Simrock 21 f.].

- ↑ a b Lieder-Edda: Völuspá 46 [= Simrock 47].

- ↑ Prosa Edda: Gylfaginning 15, 51 (citation of the Prosa Edda after Arnulf Krause: Die Edda des Snorri Sturluson. Reclam, 1997, ISBN 3-15-000782-8 ) [= Simrock 15, 51].

- ^ Translation based on Karl Joseph Simrock: Die Edda . 1851.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Sigrdrífumál 14 [= Simrock 14].

- ↑ Heimskringla: Ynglinga saga 4, 7.

- ↑ Jacob Grimm already assumes that the name is related to the Latin memor and the Anglo-Saxon minor 'mindful, remembering'. (Jacob Grimm: Deutsche Mythologie. 3 volumes. 1875-78. New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-86539-143-8 , Volume 1, p. 315) - Simek (aoO) translates as' the reminder, the wise ', related to Latin memor .

- ^ Gerhard Köbler: Indo-European dictionary. 3. Edition. 2000, keywords: * mer- and * smer- . (online) ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Gerhard Köbler: Indo-European dictionary. 3. Edition. 2000, keyword: * mer- . (online) ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Mimir is related to the Norwegian meima "measure" and is related to measuring and reflecting. (Dillmann 2001, p. 42) - Ström agrees with Friedrich Detter's derivation from Indo-European * mer- , related to Norwegian meima and Anglo-Saxon māmrian and comes to a connection with the Nordic concept of fate mjǫtudr , which is measured. (Åke Viktor Ström, Haralds Biezais : Germanic and Baltic Religion. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-17-001157-X , p. 253 f.)

- ↑ Dillmann 2001, p. 38 ff.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Golther: Handbuch der Germanischen Mythologie . Hirzel, Leipzig 1895. New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-38-X , p. 216.

- ^ Translation after Arnulf Krause: The songs of gods and heroes of the Elder Edda. Reclam, 2004, p. 65 [= Simrock 141].

- ↑ a b Dillmann 2001, p. 42.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Grimnismál 25 [= Simrock 25].

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Fjölsvinnsmál 19-22 [= Simrock 19-22]

- ↑ Derolez 1959, p. 274 - John Lindow: Handbook of Norse Mythology. USA 2001, ISBN 1-57607-217-7 , keyword: Mimir. Lindow only provided that Mimameidr = Yggdrasil.

- ^ Prosa-Edda: Gylfaginning 53. Old Norse hodd means 'gold, treasure': Gerhard Köbler: Old Norse dictionary. 2nd Edition. 2003, keyword: hodd . (online) ( Memento of the original from April 12, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Vafþrúðnismál 45 [= Simrock 45], Prose-Edda: Gylfaginning 53 [= Simrock 53].

- ↑ Derolez 1959, p. 271. - Åke Viktor Ström, Haralds Biezais: Germanic and Baltic religion. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-17-001157-X , p. 254.

- ↑ Lieder-Edda: Hávamál, 138 f. [= Simrock 139 f.]

- ↑ Dillmann 2001, p. 41. - With the same result: Simek (aoO)

- ↑ Eyrbyggia saga, Chapter 43; Þorstein's þáttr bæjarmagns, chapter 9.

- ↑ Eduard Neumann, Helmut Voigt: Germanic mythology. In: Hans Wilhelm Haussig , Jonas Balys (Hrsg.): Gods and Myths in Old Europe (= Dictionary of Mythology . Department 1: The ancient civilized peoples. Volume 2). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-12-909820-8 , p. 70.

- ↑ a b c Davidson 1988, p. 77.

- ↑ See Dillmann 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli (Ed.): Concise dictionary of German superstition . Volume 1, p. 638.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Golther: Handbuch der Germanischen Mythologie . Hirzel, Leipzig 1895. New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-38-X , p. 420.

- ↑ a b Duden: The dictionary of origin. 2nd Edition. 1989, keyword: moon.

- ↑ Wolfgang Golther: Handbook of Germanic Mythology . Hirzel, Leipzig 1895. New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-38-X , p. 420. - Eduard Neumann and Helmut Voigt: Germanic mythology . 1973, p. 71.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Golther: Handbuch der Germanischen Mythologie . Hirzel, Leipzig 1895. New edition: Marix, Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-937715-38-X , pp. 227, 420. - Eduard Neumann and Helmut Voigt: Germanic mythology . 1973, p. 71.

- ↑ Dillmann 2001, p. 41 f.