Baryton

The baryton (also masculine "the baryton"; earlier also Pariton , Paridon , Barydon , Bordon ; Italian viola (di) bordone or bardone ) is a string instrument of the early 17th century, which was mainly used in the 18th century. In addition to the playing strings, the baryton has sympathetic strings that can be plucked with the left hand and give it a distinct reverberation. Leopold Mozart calls it "one of the most graceful instruments".

construction

The baryton has the size and tuning (DG cea d ', also EA dgh e') of a tenor bass viol . A seventh string on Contra-A is rare, its use is not documented in the music of the 18th century - the D and G strings are hardly mentioned in literature. The instrument is held between the legs like a viol. The bow was held in the upper or lower grip, depending on the player's personal preference. If necessary, a metal or wooden stand could be used on the instrument, the spike.

In addition to the playing strings of gut metal resonance, drone or Aliquotsaiten are on the blanket tensioned, similar to the d'Viola amore or Hardanger fiddle . Prince Esterházy's instrument has nine sympathetic strings, typically in the tuning A de fis gah cis 'and d'. They give the instrument a sharp, overtone-rich sound that sets it apart from the most commonly used accompanying instruments, the viola and cello. The metal strings can be retuned to maximize resonance. Andreas Lidl , cellist in the Esterházy court orchestra from 1769 to 1774, increased the number of brass metal strings to 27 pieces. A baryton "ex Lidl" by Joachim Tielke 1687 is preserved in the Horniman Museum in London (it is no longer in its original condition); The instrument from 1686 in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, also by Joachim Tielke, is better preserved. Finally, there is a fragment of a baryton from the same workshop. The sympathetic strings are either attached to pins on the lower block and are guided over a second (mostly inclined) bridge - as in the modern replica shown. Often they are also attached to blocks that are glued to the ceiling, similar to the bridge of a concert guitar.

What is unique about the baryton, however, is that its neck has a large window at the back through which the ten or so metal strings can be plucked with the thumb of the left hand. The resulting sounds are similar to that of a harpsichord or mandolin . In the early baroque baryton, the sympathetic strings were more in the contra-octave range, while the gut playing strings were mostly tuned a third higher. The point was to be able to accompany arias with a plucked bass and one or two bowed voices. In the baryton works by Joseph Haydn there are small Arabic numbers under some notes . The so-called notes are not deleted, but plucked with the thumb. At the same time, the respective numbers indicate the sequence of pages and the mood of the response page. If you increase the number of sympathetic strings, chromatic accompaniments are also possible, but this makes the instrument, which is already complicated to play, completely unwieldy, as Schilling described in 1842 with reference to the virtuoso Sebastian Ludwig Friedel: “... just the neck, how the fingerboard and the hidden harp [meaning the sympathetic strings] were so broad that it would have been difficult to find hands in creation that could handle both at the same time. "

The fascination of the baryton in the late 18th century, the so-called "Age of Sensibility ", also has a philosophical-psychological reason. Mechanics was then considered a "miracle science". One had understood the phenomenon of vibrations and their spread to other bodies. This knowledge of the resonance was transferred to the soul kinship - the sympathy (in English the resonance sides are called sympathetic strings), which only shows itself when the vibrations of one soul are taken over by the other. In baryton, this is evident between the two contrary materials, gut and metal, which stimulate each other to vibrate.

variants

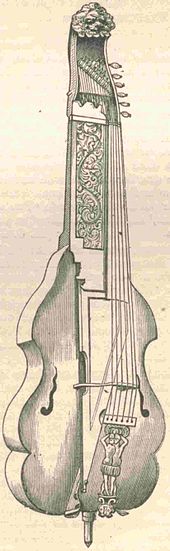

The instrument of Prince Nikolaus von Esterházy can be seen as exemplary and formative for a "family look". Even today's replicas are mostly based on this model and similar, although such an infrequent instrument almost challenges experiments and your own creations. The pictured instrument owned by Manfred Herbig was built in 1973 by Wolfgang A. Uebel in Celle based on historical models. The shape of the body , the flame holes and the rosette are part of the family appearance of the baryton . The “Singing Farmer” as the upper end, here after an instrument by Simon Schödler in Brussels, characterizes the instrument type like the snail the violin family or the Cupid (Amor) the viola d'amore. The body is designed like a gamba and has a flat bottom with a kink in the upper area.

distribution

The baryton was always a rare instrument that found a certain distribution in southern Germany and Austria at the end of the 18th century . In the early baroque and baroque periods it was hardly used except in the operas by Attilio Ariosti (1666–1729). The most prominent baryton player was Nikolaus (Miklós) I, Prince of Esterházy (1714–1790), known as the “splendor lover”. According to the employment contract, the prince regularly asked Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), who had been in his service from 1761, to compose “for the gamba”. Haydn wrote a total of 175 works with baryton, including 126 trios for baryton, viola and cello. Research assumes that the prince played intensely from 1765 to 1775 and then turned his musical interest more towards the new puppet theater. It is thanks to his passion that the instrument has not been forgotten. Long before his reign (1762–90), in 1750 Johann Joachim Stadlmann in Vienna made a particularly valuable instrument with elaborate carvings and a fingerboard made of ivory and ebony . Such an item was of course also a showpiece and capital investment for the treasury - a "cabinet item". Andreas Lidl, cellist in the Esterházy court orchestra from 1769–1774, caused a sensation and recognition in Paris, London and Germany with the baryton. The last great baryton soloist of the 18th century was Karl Friedrich Abel (1723–1787).

With the change in sound aesthetics at the beginning of the 19th century, the baryton also almost completely disappeared. The Bohemian cellist, conductor and composer Vinzenz Hauschka (1766-1840) was admired in Vienna as a baryton player, among other things. In Berlin , the royal Prussian cellist Sebastian Ludwig Friedel (1768 - approx. 1830) from Mannheim was also celebrated as an extraordinary barytonist (Schilling). He owned the instrument by Joachim Tielke, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum, dating from 1686 (with a lion's head, flanked by two dragons) and after several modifications had the number of sympathetic strings increased to 22. This instrument is shown in the drawing (top right). Friedel initially received it as a "loan" from Elector Carl Theodor in Mannheim. The previous owner was King Maximilian of Bavaria in Munich (Hellwig).

As part of the “first renaissance of historical instruments and performance practices” at the beginning of the 20th century, the baryton as well as the viola da gamba experienced a revival. Christian Döbereiner , Karl Maria Schwamberger, János Liebner , August Wenzinger and Johannes Koch are named as early protagonists .

Compositions

The 176 works with baryton by Joseph Haydn have already been mentioned. These include duets for two barytones, two quintets (baryton trio and two horns), six octets (string quartet, baryton, double bass, two horns), concerts with three-part string orchestra and more. Prince Nikolaus I, Prince of Esterházy, also ordered works with baryton from other composers, such as 24 trios from Luigi Tomasini , the concertmaster in the court orchestra led by Haydn. Only three of them are with viola, the others with violin. Alfred Lessing found a 25th baryton trio in the Heiligenkreuz monastery near Vienna. 24 trios by Joseph Burgksteiner (?) And Anton Neumann (1740–1776) have also been preserved. Andreas Lidl (approx. 1740–1789, also wrongly called Anton), 1769–1774 cellist in the Esterházy court orchestra, published six trios as opus 1 in London in 1776, another six in Paris and another six in London (see RISM ). Although these were published for violin or flute in the first part, it can be assumed that Lidl played them on the baryton, because Haydn himself had already chosen this route of publication. The works with baryton by Sebastian Ludwig Friedel were probably never printed (Schilling) and therefore seem inaccessible, if not lost. By Vincent Hauschka (1766-1840) five quintets (baritone, string quartet) and five duets (baritone, cello) are called, they are considered as missing.

In the early 1960s, the Hungarian barytonist and composer Janós Liebner (* 1923) discovered the manuscript of a series of Italian canzonetti, signed “Vincenzo Hauschka”, for various voices with baryton accompaniment, and performed some of them publicly in the following years.

With the rediscovery of the baryton in the 20th century, works were composed again. In 1979 and 1983 Manfred Herbig wrote two three-movement trios for his “Braunschweiger Barytontrio”. In 1984 he wrote a solo cantata for tenor, baryton trio and harpsichord ( Jesus in the desert ). Manfred Spiller, Wolfenbüttel, wrote four trios, and Heinz-Albert Heindrichs , Gelsenkirchen, wrote the original bagatelles in one movement for the “Braunschweiger Barytontrio”. The Trio Maria Aegyptiaca by Wolfgang Andreas Schulz, named after the mural by Tintoretto in Venice, was premiered in 1984 by the “Braunschweiger Barytontrio”. Peter Michael Hamel wrote for Jörg Eggebrecht Mittlerer Frühling: six duo miniatures for viola and baryton , in which he uses the 16 sympathetic strings in different ways. In the 1960s and 1970s, around a dozen contemporary works were composed for Janós Liebner, including by the French Henri Tomasi (Troubadours 1967), the English Clive Muncaster (continuous obligatory solo part in the oratorio The Hidden Years and two arias from it for soprano with baryton accompaniment 1968), by the Hungarians György Ránki (solo pieces 1959) and Ferenc Farkas (Sonatina all 'antica 1962, Concertino 1964, five troubadour songs for soprano and baryton 1968, Bakfark Variations for baryton solo 1971), by the Germans Hoffmann ( Concert) and Grabs (sonata), by the Austrians Eder de Lastra (solo pieces) and Dallinger (sonata), as well as two authorized and dedicated transcriptions by Frank Martin (Chaconne, Sonata da Chiesa).

No details are known about a baryton trio written in 1985 by Sándor Veress (1907–1992) and a concert (Divertimento concertante 1971) for baryton and chamber orchestra by Janós Liebner.

Árpád Pejtsik has reconstructed some of Haydn's baryton duos and transcribed them for two cellos.

literature

- Robert Eitner , Franz Xaver Haberl : Bibliography of the music collections of the XVI. and XVII. Century . Liepmannssohn, Berlin 1877.

- Efrim Fruchtman: The baryton. Its history and its music reexamined . In: Acta Musicologica 34, 1962, ISSN 0001-6241 , pp. 2-17.

- Georg August Griesinger: Biographical Notes on Joseph Haydn . Breitkopf and Härtel, Leipzig 1810.

- Friedemann and Barbara Hellwig: Joachim Tielke. Ornate baroque musical instruments . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Berlin / Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-422-07078-3 .

- Günther Hellwig: Joachim Tielke. A Hamburg lute and viola maker of the baroque era . Verlag Das Musikinstrument, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-920112-62-8 , (series of specialist books Das Musikinstrument 38).

- Haydn Institute (Ed.): Joseph Haydn. Works . Henle, Munich et al. 1958–, (in particular series 14, vol. 1–5: Barytontrios No. 1–126 ).

- Anthony van Hoboken : Joseph Haydn. Thematic-bibliographical catalog of works . Schott, Mainz 1957–1978, ISBN 3-7957-0003-5 , (Group XI (trios), XII (duos), XIII (concerts)).

- János Liebner : The baryton . In: The Consort 23, 1966, ISSN 0268-9111 , pp. 109-128.

- Leopold Mozart : Attempt at a thorough violin school . Lotter, Augsburg 1756.

- Carl Ferdinand Pohl , Hugo Botstiber : Joseph Haydn . 3 volumes. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1875–1927, (also reprint: Sendet, Wiederwalluf near Wiesbaden 1971).

- Gustav Schilling : Encyclopedia of the Whole Musical Sciences, or Universal Lexicon of Tonkunst . 7 volumes. Köhler, Stuttgart 1835–1842, (also reprint: Olms, Hildesheim et al. 1974), (quoted from Hellwig 1980).

- Carol A. Gartrell: A History of the Baryton and Its Music - King of Instruments, Instruments of Kings. Scarecrow, Plymouth 2009, ISBN 978-0-8108-6917-2 , (English).

Web links

- Roland Hutchinson explains the baryton

- J. Haydn, Divertimento

- The website for Joachim Tielke , of whom at least three barytones or fragments have been preserved.

- Esterhazy Ensemble

Individual evidence

- ↑ Andreas Lidl in the Austrian music dictionary, accessed on March 29, 2017