Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel

Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel Op. 24 are a piano work by Johannes Brahms .

Musical historical classification

At the age of 28 Brahms wrote the Handel Variations in September 1861 in Hamburg-Hamm . They are considered the most important of his five cycles of variations for piano for 2 hands and place him as a master of this genre between Ludwig van Beethoven and Max Reger . The work uniquely combines baroque music with music of high romanticism . It contains a siciliano , a musette , a canon and a fugue . Like Bach's Goldberg Variations , Beethoven's Diabelli Variations and Schumann's Symphonic Etudes , Op. 24 is one of the most important variation works in piano literature.

Autographs, appropriation and early reception

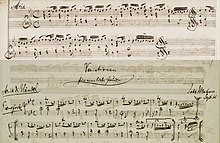

Brahms wrote the first autograph “Variations for a dear friend” and gave it to Clara Schumann , Robert Schumann's widow .

"I made you variations for your birthday that you still haven't heard and that you should have practiced for your concerts long ago."

Brahms made a second autograph as a template for the first print at Breitkopf & Härtel, correcting some things and also taking over some of the corrections already entered in the first autograph. There were probably other small changes made while proofreading. Brahms left out the dedication to Clara Schumann in the print.

Before the work was published by Breitkopf & Härtel in July 1862 , Brahms presented it to a Hamburg private group on November 4, 1861. Clara Schumann also played it in Hamburg on December 7th and was disappointed by Brahms' indifference. According to Clara Schumann, Brahms said "he could no longer hear the variations, it was terrible for him to have to hear something about himself, to sit idly by [...]". Brahms himself performed his op. 24 a total of eighteen times in public, including in Oldenburg (Oldenburg) , Vienna , Zurich , Budapest , Dresden and Copenhagen . In negotiations with the publishers Breitkopf & Härtel, he called this work his “favorite work” and considered it “much better than [s] an earlier work and also much more practical and therefore easier to distribute”.

At the only personal encounter with Richard Wagner in his Viennese apartment on February 6, 1864, Brahms played his op. 24 after Max Kalbeck “at Wagner's express request”, who then “spoke convincingly […] about all the details of the composition”, “den showered young composers with appreciation "and concluded with the words:" You can see what can still be achieved in the old forms when someone comes who knows how to treat them. "

Brahms and Handel

Brahms probably came into contact with works by Georg Friedrich Handel as a pupil of Otto Friedrich Willibald Cossel and Eduard Marxsen . Unlike Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner, he wanted to hold on to traditional forms. After Gustav Jenner , he loved the expression "permanent music". In the 1850s he dealt with traditional composition techniques and especially with counterpoint . At the 34th Niederrheinischen Musikfest (Düsseldorf 1856) he heard Handel's Alexander Festival . The first major work he performed was Handel's Messiah on December 30, 1858 in the Princely Residence Palace in Detmold . After the Leipzig Bach Society , the Georg Friedrich Handel Society was founded in Halle (Saale) in 1856 . Brahms was on friendly terms with her protagonists Philipp Spitta and Friedrich Chrysander for many years. He took an active part in the creation of Bach and Handel's complete editions , which he collected in his library in Vienna , alongside those by Frédéric Chopin , Heinrich Schütz and Robert Schumann . He also transcribed two series of Handel chamber duets that Chrysander had discovered and earmarked for publication in his monumental Handel edition.

construction

From the exchange of ideas by letter with his friend and composer colleague Joseph Joachim and with the Herzogenberg couple, it can be inferred that Brahms avoided the type of fantasy variation in the Handel Variations and, similarly to op. 21, “a new, strictly am Theme-oriented variation concept "aimed at. This work of variations is therefore based “on the harmonic-metric shape of the thematic material, based on the bass structure”. Overall, there is "the need for a strictly formal system in which [...] all levels of the original - melody, metrics, harmony - should equally be the basis of the variation." The fugue theme also turns out to be a variation of the theme melody from the antecedent of the aria .

Like the aria, most of the variations and the fugue are in B flat major and in 4 ⁄ 4 time . The variations stay close to the theme.

Aria

Brahms chose the aria of the Suite in B flat major from the second collection of George Frideric Handel's Suites de pièces pour le clavecin , Handel Works Directory 434, which was published as a pirated print in England in 1733, as the theme , which serves as a variation theme in the suite. He had found it in an old-fashioned sheet music print. Brahms took over the aria almost true to the notes, only instead of Handel's symbols for bulging trills he used trills (tr) - except in the fourth measure of the antecedent and in the prima volta of the suffix - used the treble clef instead of the soprano clef, and combined the accompanying parts in chords and slightly modified the final measure.

According to the old rule, the theme consists of two four bars , i.e. a front and a trailer, which are each repeated. A slightly modified phrase, basically repeated eight times, forms a “variation in the theme”. The permanent, but slightly different, alternation b – a – b in the lower voices of the antecedent and in the second and third bars of the subsequent movement also contributes to this. The aria begins in bar, but in the following the second eighth of every fourth beat appears as bar . Because of this and the variations within the theme, it has an open and closed character at the same time.

Variations

Brahms rearranged the order of Variations 15 and 16 on the first autograph. This shows that he saw the individual variations in an overall context that - also through this change - should ensure a meaningful development from the theme to the fugue. Clearly in the notation of this autograph, but also of the first edition, the variation section looks like a largely continuous, coherent musical text, although there are groupings. This is ensured by thematic references within the groups and, for example, fermatas and an occasional new beginning in a new line in the first autograph. Be that the variations experienced as a contiguous organism has its cause in the retained 4 / 4 ¯ clock, the variation in the 10th through eighth triplets already in the direction of the 4 / 4 -Takte representing 12 / 8 -Takte 19 ., the 23rd and the 24th Variation. Accordingly, a unifying four-meter meter is retained .

|

Variation I. The first variation is seamlessly linked to the theme by a prelude of five 32nd notes in the seconda volta of the end of the theme: in the upper part on the melody structure, in the lower parts on the alternating notes and on the basic bass. Right and left hands form complementary, continuous 16th notes in staccato . Accentuated chords on half beats create syncopated effects, so that the 16th note movement fades into the background. |

|

Variation II The second variation forms a stark contrast to the first, rhythmically accentuated staccato variation: legato is prescribed throughout . The contours are blurred by an animato superimposition of eighth notes and eighth note triplets as well as chromatic alternating notes in the upper part, which is characterized by the melody of the theme, and chromatic passages in the lower parts. Common crescendos and decrescendos within a piano support the ups and downs of this variation. The second variation flows seamlessly into the third. |

|

Variation III In the third, Dolce and p to be played variation alternate right and left hand - accompanied by the staccato tapped chords and bass tones - with Provision for melody structure of the thread from. In the aftermath, the tendency towards the minor variant already indicated in the second variation becomes clearer, which then characterizes the 5th and 6th variations. The 3rd variation also merges seamlessly into the next, visible in the incomplete final bar in the seconda volta , the missing sixteenth of which is added by the prelude to the 4th variation. |

|

Variation IV In stark contrast to the previous variation is the fourth variation that immediately follows. It also lives from a thematic dialogue between the left and right hand. The octaves to be played risoluto and staccato are always filled with chords when they are supposed to set rhythmic accents, especially when they appear syncopated as separate sforzato- 16ths. The follow-up confirms the turn to the minor variant, which was already carried out in the previous variations. |

|

Variation V and Variation VI The fifth and sixth variations are in the tonic variant in B flat minor and use the Neapolitan that reinforces the minor effect . They form a related pair. While in the fifth variation , entitled espressivo , the melody of the theme in the upper part, provided with short crescendi and accents, is processed and the lower part plays dissolved chords, the two octave voices are soft, legato and without accents, The canon of the sixth variation set in the reversal at the beginning of the subsequent clause has equal rights. Both voices quote the 16th note motif from the first measure of the theme. A fermata on the final bar of the last bar causes a caesura before the next pair of variations. |

|

Variation VII and Variation VIII These two variations, which merge into one another and are to be performed con vivacitá, are characterized by a rhythm that alternates between dactylic and anapaestic effects and is preformed in the aftermath of the aria . While this rhythm covers all voices in the seventh variation, it is used in the eighth variation to give the organ points on the tonic and the dominant an ostinatic rhythm in the lower part. The two upper voices of the eighth variation are composed in double counterpoint , which means that the afterthought of the eighth variation is extended to double its length. In both variations there are deviations , in the seventh after D minor and E flat major, in the eighth after B flat minor and E flat major. Even after this pair of variations, a caesura arises through a fermata over the closing stroke, but the incomplete last bar also indicates that the eighth and the ninth variation, which begins with a 16th note, belong together. |

|

Variation IX The ninth variation, played poco sostenuto and legato , in the lower part progressing in octaves brings the theme upwards diatonic and then in the inversion chromatically filled downwards several times over organ points on different tonal levels and with the use of the pedal. The octaved upper part consists of a downward chromatic scale, which is expanded with triplet figures. The two-bar sections begin with Sforzati on the 16th note upbeat and the following one of the measure and end after a decrescendo on an intermediate dominant or the tonic of the respective section. In the second part of the last two bars, the lower part does not lead down, but up to the octaved b ′ , the end of the scale. The tonal levels are successively B flat major, D major, B flat major, D major, F major, B flat major, F sharp major = G flat major and B flat major. There is a fermata above the final chord. |

|

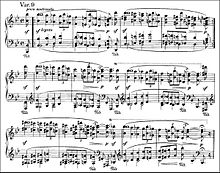

Variation X Forte and energico begin the two parts of the antecedent which, like the entire variation, are shaped by eighth note triplets. The left and right hands alternately put together the approximate basic shape of the theme melody and thereby move into ever lower octaves. The dynamic decreases and both parts end pp . At the same time, the light B flat major becomes a dark B flat minor. In the subsequent clause, which is largely forte , B minor seems to prevail after an evasion to G major, but the dynamically withdrawn ending does not offer a completely final triad, but an empty fifth with an ambivalent effect. The tension that this creates is only released in B flat major of the next variation. |

|

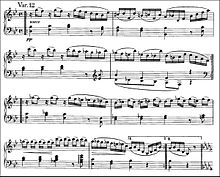

Variation XI and Variation XII The eleventh and twelfth variations form the next variation pair. Starting from the short suggestion b ′ , in the antecedent of the eleventh variation, the basic form of the theme head is played around with eighth notes once in B flat major and once in D minor. The follow-up to this low-volume, crescending variation that only crescends in the end-part with a condensed voice with two-part imitations over a chromatic upward bass line is composed. The dolce of the eleventh variation is replaced by a soave in pianissimo in the immediately following twelfth variation . As in many previous variations, the basic form of the theme melody in the antecedent is divided between the left and right hand. She plays the left hand in quiet quarters and eighth notes, the right hand plays around it with sixteenth notes. The lead and chromatic passages determine the front and the trailer, in which a turn to B flat minor and the Neapolitan sixth chord achieve special harmonic effects. |

|

Variation XIII Largamente, ma no piú is the title of the thirteenth variation. It forms the weighty center of the series of variations, is in B flat minor and should be played loudly and espressivo . In the antecedent you can see the varied basic form of the theme melody in the upper part and the alternating notes bab of the theme lower parts in the accompanying accompaniment. Deviations in the parallel D flat major change the minor character of this variation a little. The upper part, which is largely performed in sixths, already indicates the sixth passages of the next variation. |

|

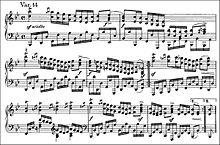

Variation XIV The fourteenth variation - back in B flat major again - mediates between the previous and the next. From the thirteenth variation it adopts the sequences of sixths in the right hand and like the fifteenth it uses the 16th note motif from the first bar of the aria . The whole variation is heavily based on the theme, particularly evident in the first part of the postscript. Lively, in free lecture (sciolto) , with a few driving forte names, sforzati and accents, it leads directly into the next variation. |

|

Variation XV and Variation XVI Originally, these two variations were planned in reverse order, but Brahms changed the order already on the first autograph. The reason for this is unknown. Both variations can be seen as a pair of variations, which is not necessarily the case as they are separated by a fermata and the sixteenth variation is directly linked to the seventeenth. They use the 16th note motif from the first bar of the aria , which also marks the sixth and the preceding fourteenth variation. The fifteenth variation is set homophonically. In the antecedent, the lower part of the sixteenth-note motif with horn fifths is octaved downwards and thus corresponds to the prescribed forte . As in other variations, Brahms avoids B flat minor in the aftermath. What is unique for the entire series of variations is that this variation has been expanded to fifteen bars. The sixteenth variation, held piano , is polyphonic . The sixteenth-note motif is varied a little and processed in two parts with closely spaced imitations . The counterpoint eighth notes should be played staccato and marcato . This variation is followed seamlessly by the next. |

|

Variation XVII In the overall quiet seventeenth variation , entitled più mosso , the downward staccato eighth notes of the upper and lower parts of the previous variation are continued. They form the framework for a two-part middle voice that is expressively designed with legato and a brief rise and fall. This middle voice is the melody carrier and is based on the basic shape of the theme melody. In the afterthought, the variation touches B flat minor and D flat major as well as E flat major supported by the pedal and ends in the main key B flat major. |

|

Variation XVIII The eighteenth variation is separated from the previous one by a fermata, although the two variations are essentially similar. The left and right hands share the varied theme melody , which is also set in two parts, but syncopated with portato and legato . Supported by the pedal, it is entwined with dismantled chords, mostly pointing downwards. The eighteenth variation also runs through the postscript in B flat minor, D flat major and E flat minor / E flat major and ends in the main key. |

|

Variation XIX The name of this variation in the first autograph was initially molto vivace and was then changed to vivace e leggiero and finally to leggiero e vivace in print . All three terms prevent the meter from four times three eighth notes from breaking down into a leisurely three meter meter of four three-eighth measures each. The result is a cheerful Siciliano that takes on a baroque character with the impact trills. The tones of the basic shape threads are distributed to the lower and middle parts, which by the emergence of with punctures is obscured and provided Prallern voices. The antecedent is repeated an octave higher, with the punctures and plumpers reaching the upper part. In the postscript, the repetition is written out because of the different prelude and the dots and rebound trills that are also shifted to the upper part during the repetition. The last bar lacks an eighth note, which can be found in the beginning of the next variation. |

|

Variation XX Although connected to the previous variation by the eighth note upbeat, the two variations only show one thing in common: the antecedent is repeated an octave higher, which this time also happens in the subsequent. Otherwise the chromatic twentieth variation offers a strong contrast to the harmoniously simple nineteenth. In the upper part, the basic diatonic form of the theme melody is filled up chromatically. In the second half of the first bar, there is a new four-note eighth note that is used several times, which also reappears in the postscript, and whose expressiveness is reinforced by a dynamic swell up to the third eighth note, followed by the immediate decrescendo . The upper part, which is initially directed upwards in eighth notes, is counteracted by a chromatically descending bass part in quarters. The postscript is characterized by first upward and then downward chromatic sections of the scale in the lower part, above which tensions build up between dominants up to the A major triad as the dominant of D major and enharmonic mix-ups, which eventually turn into the B major triad to solve. The overall quiet variation calls for strict legato . |

|

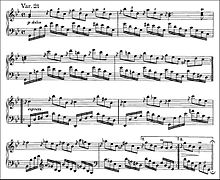

Variation XXI In contrast to the chromatic twentieth variation, the twenty-first is completely dominated by a simple, diatonic “pendulum harmony” in the parallel G minor. Apart from the main triads, only a few intermediate dominants are used. In the last bar, the minor effect is reinforced by a Neapolitan sixth chord. The special attraction of the variation, labeled piano , dolce and espressivo , lies in the superimposition of split chords, which consist of eighth note triplets in the upper part and regular sixteenth notes in the lower part. In the first autograph, Brahms pointed out that the short suggestions for the triplets should produce a pizzicato effect. Together with the b ′ of the first chord, these grace notes reproduce the basic form of the theme melody, as it is given in B flat major. |

|

Variation XXII Quiet, with the use of the pedals, and clearly emphasized tones of a drone from the duodecim bf ″ or at a few points on the organ point on b , the twenty-second variation forms a retarding stopping point before the next three variations that push towards the fugue. It has the characteristics of a musette and is therefore kept extremely simple in all musical parameters. The basic melody only sounds; its sixteenth-note figure appears in reverse and in thirty-second notes in the second part. The harmony of the subsequent clause, the volume of which increases temporarily, is reminiscent of that of the subject clause. The twenty-third variation follows immediately, adopting the idea of the organ point in the lower register. |

|

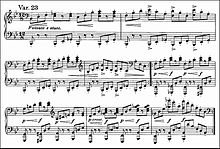

Variation XXIII and Variation XXIV The two variations to be played by vivace form a merging pair of variations with an identical shape. They are in 12 / 8 -Stroke and resemble by the tenth variation, in which the four three units of a measure, however, are listed as triplets. Their antecedents stand on an organ point (Variation XXXIII) or on a drone fifth (Variation XXIV) and oscillate between the B flat major triad and the sometimes complete, sometimes incomplete diminished seventh chord ac-es-tot. The postscripts begin with the dominant and then bring the sixth fourth chord G-C- E flat . Shortly thereafter is sat for fis reinterpreted enharmonically , resulting in a chromatic upward pressing Bass from F to B is obtained. Both variations have almost the same dynamic course, which is quiet at the beginning, repeatedly calls for short crescendos to the forte and leads overall from quiet to loud. In essence, the fifteenth variation is a figured fourteenth variation. Their broken chords, consisting of eighth notes, are partially filled with 16th notes. This creates a stringent, continuous 16th note movement in the fifteenth variation, which without any actual end brings the shortened sixth chord of the minor subdominant with the third G flat-flat. It is followed without stopping by the clear B flat major of the last variation. |

|

Variation XXV Fortissimo is followed by the twenty fifth variation. The simple harmony corresponds entirely to that of the theme. The chords of the right hand in the antecedent are the root notes of the theme melody. Right and left hands complement each other in chords to form continuous, complementary sixteenth notes. The chords are only sustained as dotted notes at emphasized points on the three of the bars, otherwise in staccato as eighth notes with a sixteenth rest separated from the corresponding sixteenth note . |

Fugue

“The fugue theme is also a variation on the Handel theme; for the first notes of the four quarters (b, c, d, es) of the fugue theme correspond to the defining melody tones of Handel's theme. The figure of the 3rd quarter in the main theme, previously used in the variations, can also be found as the 2nd quarter in the 2nd measure of the fugue theme. The fugue itself has an unusually powerful sound, its structure is free, but the details are strict. The powerful sound is expressed, among other things, in the third, sixth, octave and sixth octave courses as well as in manifold chord breaks. The severity reveals itself in the use of inversions, enlargements, coupling of the basic motif with its inversion, simultaneity of several motifs or their inversion and so on. Power of sound and stringent movements lead to great effects, especially in the organ point-like final increase, especially where after the preparation ('organ point' in the high f) the low F is struck again and again, in the middle voices motif and inversion are intertwined and the opposing voice in octaves falls from a height. "

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Otto Emil Schumann: Handbook of Piano Music. 4th edition. Wilhelmshaven 1979, p. 484.

- ↑ a b Johannes Forner : Brahms on Handel's footsteps. In: Handel in-house communications. Ed .: Friends and Sponsors of the Handel House in Halle e. V., 2/2013, pp. 24-29.

- ^ Sonja Gerlach: Foreword to Sonja Gerlach: Johannes Brahms: Handel Variations Opus 24. G. Henle Verlag, Munich 1978.

- ↑ a b c d See 1st autograph and first edition for Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel : Sheet Music and Audio Files in the International Music Score Library Project .

- ^ Oswald Jonas: The "Variations for a dear friend" by Johannes Brahms. In: Archives for Musicology. 12th year, issue 4, 1955, pp. 319–326.

- ^ Christiane Wiesenfeldt: Series - Process - Reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans-Joachim Marx, Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, p. 237.

- ↑ Johannes Brahms to Breitkopf and Härtel on April 14, 1862. In: Johannes Brahms Briefwechsel XIV. Berlin 1920, p. 67.

- ^ Max Kalbeck: Johannes Brahms. German Brahms Society, Berlin 1921, Volume 2, Volume 1, Chapter 3, pp. 116 f.

- ↑ Michael Struck: Dialogue on Variation - more precisely: Joseph Joachim's “Variations on an Irish Elf Song” and Johannes Brahms' pair of variations op. 21 in the light of the joint discussion on genre theory. In: Peter Petersen (Hrsg.): Musikkulturgeschichte. Festschrift for Constantin Floros on his 60th birthday . Wiesbaden 1990, p. 147.

- ↑ Johannes Brahms: Letter to Heinrich and Elisabeth Herzogenberg from August 1876. Quoted in context in: Christiane Wiesenfeldt: Series - Process - Reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans-Joachim Marx, Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, p. 241.

- ^ A b Christiane Wiesenfeldt: series - process - reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans-Joachim Marx, Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, p. 240.

- ↑ a b Otto Emil Schumann: Handbook of Piano Music. 4th edition. Wilhelmshaven 1979, p. 492.

- ^ Peter Hollfelder: The piano music . Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 1999.

- ^ Christiane Wiesenfeldt: Series - Process - Reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans-Joachim Marx, Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, p. 243.

- ^ Christiane Wiesenfeldt: Series - Process - Reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans Joachim Marx, Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, p. 245.

- ↑ Jane A. Bernstein: An Autograph of the “Handel Variations”. In: The Music Review. 34 / 3-4 (November 8-10, 1973), pp. 272-275, 278-281.

- ↑ Heinrich Schenker: Brahms: Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel, op. 24. In: Der Tonwille. 4th year, issue 2/3, April-Sept. 1924, p. 6.

- ^ Christiane Wiesenfeldt: Series - Process - Reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans-Joachim Marx, Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, p. 249.

- ↑ Heinrich Schenker: Brahms: Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel, op. 24. In: Der Tonwille. 4th year, issue 2/3, April-Sept. 1924, p. 25 f.

- ↑ Heinrich Schenker: Brahms: Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel, op. 24. In: Der Tonwille. 4th year, issue 2/3, April-Sept. 1924, p. 26.

literature

- Heinrich Schenker : Brahms: Variations and Fugue on a theme by Handel, op. 24. In: Der Tonwille. 4th year, issue 2/3, April – Sept. 1924, pp. 3-46.

- Otto Emil Schumann : Handbook of piano music. 4th edition. Wilhelmshaven 1979, pp. 389-492.

- Christiane Wiesenfeldt : Series - Process - Reflexivity. Change of perspective in Brahms' Handel Variations op. 24. In: Hans Joachim Marx , Wolfgang Sandberger (Eds.): Göttinger Handel Contributions. Volume 12, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2008, pp. 235–255.

Web links

- Literature by and about variations and fugues on a theme by Handel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel : Sheet Music and Audio Files in the International Music Score Library Project