Mensural notation

Mensural notation is the name of a musical notation that was used for European polyphonic vocal music from the 13th to around the 16th century . It replaced the modal notation . The difference to modal notation relates to the ability of the system of mensural notation to describe precise rhythmic durations as numerical relationships between note values.

Black mensural notation (approx. 1230–1430)

Mensural notation developed in the 13th century, driven by the differentiation of rhythms. Around 1280 Franco of Cologne formulated the rules for this notation in his treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis . After him, the first form of the black mensural notation is called Franconian notation . With the help of the French notation, the note values ( tone duration ) of the music could be clearly defined for the first time . The most important musical notes were brevis and longa . According to the three-part basic rhythm of time, the longa has the duration of three breven ( perfect longa). Within certain groupings of notes it can also last two breves (be imperfect ), for example in the sequence Longa - Brevis - Longa - Brevis ..., in which the imperfect Longa (2 beats) and Brevis (1 beat) form a three-stage unit becomes. The other note values can also be two or three times as long as the next lower note value. The following figure shows all note values of the Franconian notation, starting with the largest.

![]() Maxima or Longa duplex -

Maxima or Longa duplex - ![]() Longa -

Longa - ![]() Brevis -

Brevis - ![]() Semibrevis

Semibrevis

Franco's square script is rooted in the traditional system of signs of the liturgical Gregorian chants, but it is a pure 'artifact', not a result of many years of practice, but of considerations of music theory; Only later theorists use Franko's metric system as the basis for systems that then produce far more compositions, i.e. Franko's writing (and thus the cantus, the type of music that is now possible with it) does not replace the Gregorian notation system in church operations, but coexists with it this on a parallel line of development of western notation systems, which extends to modern notation.

Ars Nova notation

At the beginning of the 14th century, the so-called Ars Nova was accompanied by the perfect scale length, i.e. the three-part basic beat, the imperfect scale length. So now compositions were made in straight time signature , in which units of two beats formed the mensural framework. The name of the epoch goes back to the treatise of the same name Ars Nova , written around 1320 and attributed to the French music theorist and composer Philippe de Vitry . It is now assumed that this treatise is a compilation and cannot be traced back to a single author. Although the dating is considered uncertain, the Italian Marchetus de Padua is said to have described the possibility of the two-stage division in the pomerium shortly before Vitry . The first thing to do was to determine the following dimensions for the performance of a work:

- The major or maximum mode , which indicated whether the maxima were to be carried out in two or three stages .

- The mode minor or Modus indicated this for the longa.

- Tempus was the name for the measure of the Brevis or the division ratio Brevis - Semibrevis

- Prolatio for the amount of semibrevis or the division ratio of semibrevis - minima.

Since the minima were added as the next lower note value in the Ars Nova , the length of the semibreves now also had to be determined.

![]()

While modus major and modus minor could be identified through the arrangement of the pause signs, tense and prolatio could be recognized by the string signs preceding the piece. A circle (as a symbol of “perfection”) indicated the perfect, i.e. three-stage, length of the brevis ( Tempus perfectum ), the semicircle the imperfect, i.e. two-stage, length of the brevis ( Tempus imperfectum ). If a point was also drawn in the circle or semicircle, the semibrevis was considered perfect ( Prolatio perfecta or Prolatio major ). If the point was omitted, the imperfect scale of the semibrevis came into effect, which corresponds to the normal case. ( Prolatio imperfecta / minor ). Today's time sign for the 4/4 and Alla-breve time is derived from the semicircle . In Ars Nova , Vitry also introduces symbols that can also be used to note the mode (i.e. the ratio of Longa to Brevis). It is a square with three horizontal lines for the perfect mode and two for the past tense. Another feature in the manuscripts is rubefication, the red coloring. Vitry, for example, uses this method of labeling, in which black notes mean ternary and red notes a binary division.

However, if there are no signs of Modus, Tense and Prolatio, then other characteristics must be used:

- If there is a pause that extends over three spaces, it is three-stage, which is a sure sign of the existence of a perfect mode.

- If, on the other hand, there is a two-stage break, it should always be accompanied by a brevis in the perfect mode. If this pause appears between two longae, the assignment to the modus imperfectum is clear, just as if two two-stage pauses follow one another. In the mode perfectum this pause would be represented as a three-stage and a one-stage.

- If three notes of a species occur between two of the next larger genus, a perfect Modus / Tempus / Prolatio is considered likely. This determination is not certain because syncope can also occur. However, in this case a fourth, similar note would have to be nearby to close the gap in the imperfect meter.

- If two notes of the same kind are often in a row, and even more imperatively, if one of them is replaced by its rest value, this speaks for an imperfect scale. Alteration is not possible during breaks.

Five line systems were used in the Ars Nova.

Trecento notation (after Marchetus de Padua)

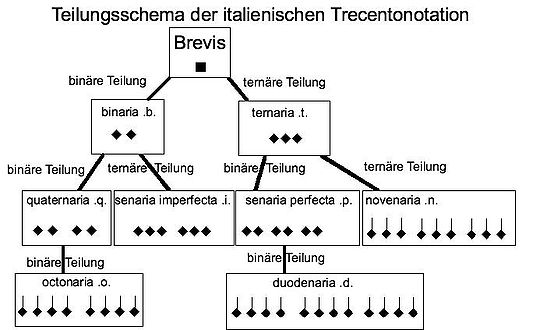

In the Italian notation of the Trecento , a different type of recording also developed at the beginning of the 14th century. This practice was described by Marchetus de Padua in his treatise “Pomerium in arte musicae mensuratae”. Here, for the first time in history, a mensural system is described in which the brevis can not only be divided into three subordinate values (perfect), but also into two values (imperfect). The previous rejection of this practice related to the Trinity of God. Now you can also divide by multiples of 2 or 3 (4, 6, 8, 9 or 12). The resulting groups of semibreves and minimae are delimited by points. The note values between two points therefore always result in a brevis.

There are up to three levels of division. These are:

- 1st level: Divisio Prima

- 2nd level: Divisio Secunda

- 3rd level: Divisio Tertia

Due to these three levels, it is only necessary to divide each note value into two or three smaller note values.

The notes, which form the smallest units in the respective division level, can be recognized by their upward-pointing necks. The types of division were indicated by the first letters of their names in dots:

-

.q. for Quaternaria (quarter division):

1st level: 2, 2nd level: 2, 3rd level: not used -

.t. for Ternaria (tripartite):

1st level: 3, 2nd level: not used, 3rd level: not used -

.i. for Senaria imperfecta (imperfect six-part division):

1st level: 2, 2nd level: 3, 3rd level: not used -

.p. for Senaria perfecta (perfect six-part division):

1st level: 3, 2nd level: 2 3rd level: not used -

.O. for Octonaria (eight division): It builds on the Quaternaria on

1st level: 2, 2nd level: 2, 3rd level: 2 -

.n. for Novenaria (division into nine ):

1st level: 3, 2nd level: 3, 3rd level: not used -

.d. for Duodenaria (twelve division) It builds on the Senaria Perfecta.

1st level: 3, 2nd level: 2, 3rd level: 2

You can see that in the third division level only binary divisions occur.

Systems with six lines were used in Trecento notation.

In the mannered notation around 1400 in southern France, the rhythmic refinement was finally taken to extremes. Now it was possible to display a change of scale within pieces without scale marks for the duration of fewer notes. For example, imperfected notes could occur within a perfect scale length, which were identified by red or hollow note symbols.

White mensural notation (approx. 1430–1600)

Before the invention of printing, choirs usually only had a single handwritten copy of a work at their disposal. Due to the enlargement of the choirs, the notes were written larger and larger so that every singer could read from the choir book. For the sake of simplicity, only the outlines of the notes were drawn, which resulted in white, "hollow" notes (just as half and whole notes are hollow in today's notation). Another reason for the transition to white mensural notation is the replacement of thick parchment with thin paper in the 15th century, because filled notes often shone through on paper.

Again, new smaller note values are added so that the bank of notes now looks like this:

Only the four major note values maxima, longa, brevis and semibrevis can occur both perfectly and imperfectly. The four small values are always two-stage. The semibrevis has been considered a tactus since the beginning of the 16th century and has the same duration in the tense perfectum and in the tense imperfectum with different lengths of brevis.

The proportion provides an additional modification of the scale system . The normal value of the notes, the integer valor notarum , is increased or decreased, i.e. the tempo of the music is changed.

In the diminutio simplex , the diminution of the note values to half of their original duration is indicated by a vertical strikethrough scale mark (circle in the tense perfectum and semicircle in the tense imperfectum ) or an inverted semicircle (in the tense imperfectum ). A proportion designation "2/1" attached to the scale mark, but which is usually shortened to the number "2", indicates a proportion dupla in which the duration of all subsequent note values is reduced by half. The proportions "3/1" and "4/1" ( Proportio tripla or Proportio quadrupla ), which are usually notated as mere numbers "3" or "4", announce a shortening of the note values in the ratio 1: 3 or 1: 4 on. Another important proportion is the Proportio sesquialtera "3/2", which is also often indicated by the mere number "3" and in which the durations of all subsequent note values are reduced to two-thirds of their original value.

In general, the following applies: The lower number of the proportion indicates a number of notes of any value before the proportion, the upper number of the proportion indicates a number of notes of the same value after the proportion, and these two sets of notes should be the same in the execution Total duration received. From the second half of the 16th century, however, a more recent interpretation of the proportions became widespread, according to which the lower number of the proportion denotes the note value that precedes the proportion in the specified number in a tactus or a battuta , i.e. in a lower and a Surcharge of the conducting movement, while the upper number indicates how often this note value is included in a conducting movement according to the proportion. If the speed of the conducting movement before and after the proportion remains unchanged, this newer interpretation gives the same result as the older interpretation. However, if the speed of the conducting movement is not kept constant, the meaning of the proportion is reduced to a change in the assignment of note values to the conducting movement. The latter was the case when the newer interpretation gradually gained acceptance in the 17th century. The names of such combinations of digits that are customary today go back to them, e.g. B. 3/2 as "three-half time", 3/4 as "three-quarter time" etc.

The proportion or scale canon, in which a single part is provided with several proportion or scale marks, reveals particular artistry. The different tone durations in the lengths / proportions result in a polyphonic and contrapuntal movement.

(See, for example, the Missa Prolationum by Ockeghem , in which a canon of proportions results from two notated voices (a discussion of the procedure in Diether de la Motte 1981), the Missa L'homme armé by Pierre de la Rue , in the the four voices result from a single voice, Si dedero by Jacob Obrecht or the Benedictus of the Missa L'homme armé super voces musicales by Josquin Desprez .)

A given cantus firmus can also be rhythmically “redefined” with the aid of proportion and scale marks (the most virtuoso example of this is the “Missa alles regretz” by Loyset Compère ).

The mensural notation was in use until around 1600, then the modern notation with its timing scheme prevailed. The notes, however, have been preserved to this day: By rounding the square or rhombic shape, the semibrevis became the whole note , the minima became the half , etc. In addition, the brevis as a double whole and, more rarely, the longa as a quadruple whole are still used today (e.g. B. in long final chords).

See also

literature

- Willi Apel : The notation of polyphonic music. 900-1600. VEB Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1962 (4th edition, ibid 1989, ISBN 3-7330-0031-5 ).

- Willi Apel: The Notation of Polyphonic Music, 900–1600 (= Medieval Academy Books . No. 38 ). 5th edition. Mediaeval Academy of America , Cambridge, Massachusetts 1953, LCCN 61-012067 (English, 464 p., Scan in the text archive - Internet Archive ).

- Thomas Daniel: Two-part counterpoint. Dohr, Cologne-Rheinkassel 2002, ISBN 3-925366-86-5 , pp. 25-27.

- Diether de la Motte : counterpoint. A reading and work book (= dtv 4371). Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich a. a. 1981, ISBN 3-423-04371-7 , pp. 39-43.

- Johannes de Muris : Notitia artis musicae et Compendium musicae practicae. Tractatus de musica (= Corpus Scriptorum de Musica. Vol. 17, ZDB -ID 401285-9 ). Edited by Ulrich Michels. American Institute of Musicology, sl 1972.

- Hermann Finck : Practica Mvsica. Rhaw, Wittenberg 1556 (Reprographic reprint. Olms, Hildesheim et al. 1971, ISBN 3-487-04097-2 ).

- Wilibald Gurlitt, Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht (Hrsg.): Riemann-Musiklexikon. Part A - Z. 12th, completely revised edition. Schott, Mainz et al. 1967, pp. 560f .: Mensural notation. P. 562: Scale mark. P. 548: Maxima.

- Jan Herlinger: Marchetto da Padova (Marchetus de Padua). In: Grove Music Online. (accessed June 5, 2012).

- Mensural notation. In: Carl Dahlhaus , Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht (Hrsg.): Brockhaus Riemann Musiklexikon (= Piper 8398 series Musik, Piper, Schott ). Volume 3: L - Q. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Schott, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-7957-8398-4 , p. 116f.

- Karl Schnürl : 2000 years of European music fonts. An introduction to notation studies. Holzhausen, Vienna 2000, ISBN 3-85493-028-3 .

- Dorit Tanay: The Transition from the Ars Antiqua to the Ars Nova: Evolution or Revolution? In: Musica Disciplina. Vol. 46, 1992, ISSN 0077-2461 , pp. 79-104.

Individual evidence

- ^ Sarah Fuller: A Phantom Treatise of the Fourteenth Century? The Ars Nova . In: The Journal of Musicology . tape 4 , no. 1 , 1985, pp. 23-50 , doi : 10.2307 / 763721 .

- ^ Roland Eberlein : Proportions in music of the 17th century, their meaning and execution. In: Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 56, 1999, pp. 29–51.