Music and architecture

There are many connections between music and architecture . On the one hand, music is often performed in rooms whose design takes acoustic requirements into account in order to optimize the listening experience; In return, the architecture of such rooms is based on the requirements of the music that is to be played in them. Mutual influences and connections up to the synthesis have determined the history and theory of music and architecture and provided both important stimuli. In the history of ideas, mathematical and geometric considerations played an important role in both arts: interval and rhythm in music, floor plan and spatial relationships in upscale architecture.

Space as a musical category

Perception of music is almost always connected with spatial impressions. This appears most clearly where a spatial arrangement of the sound generator is prescribed or where the musical sequence is structured in a significant way. This was first done on a larger scale through the practice of the Venetian polychoral group of placing singers and instrumentalists in several places within the church and adapting the musical setting to the architectural surroundings, as the Venetian St. Mark's Basilica allowed and encouraged. Many works from this period, for example Heinrich Schütz 's Psalms Davids (1619), specifically included the space in the performance. In the foreword, Schütz suggested that the individual choirs be positioned “at different Örthern” .

This style of movement, which he took over from Giovanni Gabrieli and continued together with Adrian Willaert , essentially continued the dialogue principle that was already present in the antiphons of Gregorian chant . In terms of internal music, the principle was productive in the Concerto grosso , which represented the baroque terrace dynamics alternating between two separate groups of instruments. This was already preformed in Gabrieli's Sonata pian e forte (1597), which graduated the dynamic degrees by adding or leaving out the individual choirs. At the same time, the concert groups play in different registers , so that the pitch impression controls the perception of space psychoacoustically , as the entire pitch space can only be perceived in the tutti passages . The plant not only unfolds the external architectural space, it also projects it into the internal musical space, so that the concrete spatial situation of the respective performance no longer determines the acoustic impression alone.

Staging the space

The consideration of the architectural space partly had the consequence that composers tried to visualize the spatial effects in the music. In romantic music, this sometimes happened through theatrical effects.

Hector Berlioz ' Grande Messe des Morts op. 5 (1837) for the dead of the July Revolution staged the space of the Paris Invalides . In addition to the huge orchestra and choir , the score provides for four brass choirs , which stand in the corners of the cathedral as a distant orchestra to the four cardinal points .

Franz Liszt wrote in the final movement of his Faust Symphony (1854/57) as a dramaturgical effect that the male choir should "solemnly move in" .

The composer's performance instructions give rise to technical performance difficulties if the performance location does not allow an accurate performance for technical reasons. In addition, the reception conditions have changed. The modern, darkened concert hall allows only limited visual orientation, as it corresponds to the ideal of concentrating on the acoustic event, as it arose from the ideas of the bourgeoisie in the 19th century; Since then, the venue has been a place of devout art contemplation. Based on the model of Richard Wagner's Bayreuth Festival Hall , which withdrew the orchestra pit from the view of the public, the city hall (1901/03) was built in Heidelberg , which had a retractable orchestra room. The spatial presence of the musicians should no longer distract the audience from listening.

Architecture in musical aesthetics

Likewise were metaphors for architectural contexts in the aesthetics of music on, since the modern conception of the musical work had become established as a permanent art object. In his Musica poetica (1643), Johann Andreas Herbst compared music with a building. Who was a composer ,

"[...] who cannot sing alone, but who at the same time knows how to produce a new opus or Werck [...], hence it has been called a building by some Fabricatura or Aedificium."

Architectural metaphors also often show Ernst Kurth's form thinking . About the relationship between the two subjects of the fugue in C sharp minor from Johann Sebastian Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier I (1722) he found:

“If the first […] was the basic will of a heavy building, then these movements of the uniformity of a calm undulating line contain a kind of floating movement, which only appears as a contrast to the compact building and contains a kind of height sensation compared to that Imagination of clear height above an architectural structure of emerging form movement, e.g. B. a Gothic cathedral. "

Musical influences on the architecture

Even in antiquity , it was believed that music and architecture were related. In his lecture Philosophy of Art (1803), Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling described architecture as “frozen music” , in the opinion that “(...) a beautiful building is in fact nothing other than music perceived with the eye, not in of time, but rather a (simultaneous) concert of harmonies and harmonic connections understood in the sequence of rooms ” . Johann Wolfgang von Goethe called it in his maxims and reflections (1833 posthumously) a "silent art of music" .

A defining example of the early 20th century was Ferruccio Busoni's architectural analysis of his Fantasia contrappuntistica (1910), which he made in the form of a cathedral . Conversely, Otto Bartning's expressionist Schuster house (1921/24) in Wylerberg was addressed in contemporary architectural criticism as a “boldly constructed symphony” , the sentences of which corresponded to the individual rooms.

Ancient and Middle Ages

The original interpretation of the family relationships was based on their mathematical foundations. The Pythagorean view of music was essentially based on the science of interval proportions : they believed that the entire cosmos was pervaded with a harmony of numbers and could be abstracted by numbers. Music is a phenomenon of numerical harmony, since vibrating strings would result in consonant intervals if their lengths were in simple, integer relationships to one another. The Pythagorean understanding resulted in the classification into the logical-rational quadrivium within the Artes liberales , which determined musical thinking up to the Renaissance .

The tetractytes 1: 2: 3: 4 and 6: 8: 9: 12 were considered perfect numerical ratios . A series with the proportions 1: 2: 3: 4: 8: 9: 27 was designed by Plato in the Timaeus . The series include the musical consonances, the harmony of the spheres and the structure of the human soul. From this metaphysical meaning it follows that only those arts that use numbers, measurements and proportions can produce beauty. For Plato and Aristotle, architecture is one of them, which they place above painting and sculpture . However, since it did not belong to the liberal arts, it tried to place itself on an equal footing with music by expressly making use of musical numerical relationships. The fact that the Greek temple complexes of Paestum correspond to the numerical proportions of melody types in the floor plan as in the architectural details speaks for a practical use of this concept .

The architectural theory continued in the 1st century BC. With Vitruvius's De architectura libri decem . In this work Vitruvius demands that an architect must first understand music theory and emphasizes that there are only six consonant intervals that he uses in practical use to calculate the rope tension of catapults and to specify the size of sound vessels in the theater . However, he does not draw any consequences for the building aesthetics.

The Middle Ages combined the ancient harmony of the spheres with Christian ideas. Boëthius and Augustine von Hippo took up the idea of musically proportioned architecture again. Gothic cathedrals and monastery churches show musical numerical relationships in the main dimensions of the floor plan and facade. The temple of Solomon was used as a model , in whose design Petrus Abelardus discovered consonances. The preferred mathematical proportion of numbers was the golden ratio, which is now associated with Christian symbolism and which also occurs in nature, and the endless Fibonacci sequence related to it . Based on her model, Guillaume Du Fay composed the motet Nuper rosarum flores (1436) for the consecration of the cathedral. The proportions of the four motet parts in the ratio 6: 4: 2: 3 and the number of notes within the individual voices process the dimensions of the temple in Jerusalem .

Renaissance

It was not until the Renaissance that the musical model of the aesthetics of numerical proportions developed into a true doctrine of proportions, which now also included painting and sculpture in its considerations.

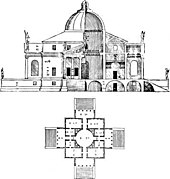

In his architectural treatise De re aedificatoria, the theorist Leon Battista Alberti defined beauty as the reflection of simple interval relationships. On the basis of the Pythagorean consonances and the large whole tone in a frequency ratio of 8: 9, he developed ideal proportions for room areas: 1: 1, 2: 3 and 3: 4 for small, 1: 2, 4: 9 and 9:16 for medium, 2 : 6, 3: 8 and 2: 8 for large rooms. He received them from compound consonances, e.g. B. 4: 9 from two fifths (4: 6: 9), 9:12 from two fourths (9:12:16). Alberti also applied his system to the subdivisions of areas and the height of the rooms.

It is not contradictory within this aesthetic that the sum of the intervals - 4: 9 ninth and 9:16 seventh - are each dissonances ; they do not represent the real sound. In his own buildings Alberti went beyond his theoretical approach and used intervals that do not belong to the consonances mentioned by Vitruvius, mainly those formed from the five as well as the third and sixth . He realized the idea u. a. on the facade design of the Palazzo Rucellai in Florence (from 1455).

Andrea Palladio continued the development with a system of proportions, which he set out in the Quattro libri dell'architettura (1570). The ratios 4: 5, 5: 6 and 3: 5 took a leading position. This can be interpreted as a reaction to the music theory of the 16th century, according to which the Pythagorean thirds (64:81 and 27:32) should be replaced by the pure intervals (4: 5 and 5: 6) in order to introduce them as consonance. Gioseffo Zarlino's Le istituzioni armoniche (1558), the first music-theoretical work of the modern age, concluded this development from the opposite side, so that the thirds were no longer considered dissonant.

From the 17th century

The musical reference to numbers in architectural theory ended with rationalism . Claude Perrault took the most violent stand in the French controversy against the view that beauty is based on numbers. He introduced the taste judgment, which is still valid today, as a guideline in the aesthetic discussion. Nevertheless, the change from the Pythagorean concept of harmony to aesthetic relativism was slow.

In the 19th century Albert von Thimus dealt with the Pythagorean harmony; Hans Kayser took up his suggestions again in basic harmonic research. Individual architects such as Theodor Fischer or André M. Studer dealt with the theory of musical proportions. The best-known and most far-reaching new development based on this is Le Corbusier's Modulor system. Le Corbusier called music and architecture sisters and assumed that their proportions were perceived in the same way. For the serial music of the 1950s, Modulor became a point of reference in the search for a system of measurement for the musical parameters .

Le Corbusier's pupil Iannis Xenakis , who worked with him as an architect, introduced the theory of proportion into new music with the composition Métastasis (1953/54) . The six tempered intervals correspond to six tone durations, which, analogous to the intervals, form a geometric sequence ; the tone lengths are created by addition. Xenakis' scheme of proportions thus relates to the properties of the golden section.

Finally, he translated the work back into the formal language of architecture. From the graphically noted glissandi of the string instruments, he obtained a host of tangents to a hyperbola . They inspired him to design the Philips pavilion at Expo 58 in Brussels out of curved shells. The building erected by Le Corbusier and acoustically designed with Edgar Varèses tape composition Poème électronique became the starting point for the development of sound art and multimedia .

Forms of synthesis

The end of the universally valid principle of harmony led to synthetic attempts that wanted to integrate the interaction of the arts into one art. Richard Wagner's idea of the total work of art that architecture had to serve was significant for the 19th century . Wagner's view was aimed at creating a functional spatial environment for the drama , which became a musical drama with music , as he postulated in his work The Work of Art of the Future (1849–1852) against the “decay of the arts”. Otto Brückwald's Festspielhaus in Bayreuth met this requirement . Its interior created a mood in which the audience felt included in the action on the stage.

The idea of art synthesis was widespread and often taken up in Expressionism. Many, often never executed, designs emerged, and the vision of awakening people into cosmic consciousness to overcome social boundaries came into focus. Architectural plans for theaters and concert halls were no longer functional, but instead were given a synthetic aesthetic as “sounding architecture”. Architects such as Hans Poelzig and Wenzel Hablik were influenced by this , and Hans Scharoun's Berlin Philharmonic (1957–1963) was also influenced by this. Based on the idea of musical architecture, Bruno Taut wrote in 1920 Der Weltbaumeister , an “architectural drama for symphonic music” that depicts the emergence of musical and architectural form from a cosmic primordial foundation.

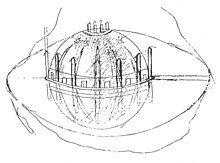

Alexander Nikolaevich Scriabin planned a spherical temple in India for his Mysterium (1914) . There, the total work of art of word, sound, color, movement and fragrance should reveal the unity of man and the cosmos to those who experience it. Ivan Alexandrowitsch Wyschnegradsky pursued similar goals with the Light Temple (1943/44), in which a play of light and colors should be visible, analogous to music. The composers saw the architectural framework of their projects as an integral part of their dramatic plot. Both sketched huge hemispheres as symbols of the cosmos, just as Étienne-Louis Boullée's cenotaph for Isaac Newton (1784) and other of his designs already showed gigantic spheres.

multimedia

In the multimedia concepts of the second half of the 20th century, the arts and forms of perception gradually flow into one another; Designations such as "sound sculpture" or "sound architecture" indicate it. Performance , happening or fluxus influenced this notion from the side of art. Architecture is increasingly defined in terms of time, music in terms of space. Architecture becomes audible, music accessible. The aim of the synthesis attempts is to expand the sensual experience that the experiencing person helps to shape.

Karlheinz Stockhausen has been using sound movement in space as a compositional means since the electronic works Gesang der Jünglinge (1955/56) and Contacts (1st version 1959/60). Sound sources are loudspeakers distributed in the room , which allow the sound to wander through the room, so that sound paths and architecture overlap with the space around the listener. Different, overlapping sound movements create polyphonic layers in the room. Stockhausen realized his own ball idea, reminiscent of Scriabin and Wyschnegradsky, at Expo 70 in Osaka ; the listeners sat in his ball auditorium on a sound-permeable floor, surrounded by music. Similar designs were Bernhard Leitner's sound installations from loudspeakers, e.g. B; Sound room (1984 at the TU Berlin ). In this way, architecture becomes, like music, an art of the times, since it only exists as long as the music that builds it sounds is heard. Erik Satie had already followed something similar in the Musique d'ameublement . The pieces named wallpaper , floor and curtain constitute the components of a room. Conversely, Stockhausen used movement in architecture to create sound spaces. In the performance Musik für ein Haus (1968) he let the listener walk through rooms like visitors to an art exhibition in which different compositions are played independently of one another; the music is recorded, eventually the recordings increasingly replace the playing instrumentalists, so that the sound space is retained.

Architecture and room acoustics

During the Renaissance, awareness of the effect of space on the sound of music awoke. The appearance of multiple choirs in the 16th century used the sound effect of several ensembles in the church. At the same time as the music practice at the Venetian Cathedral began, research into spatial effects and the demands on the music that plays. The areas of chamber music and church music were separated according to instrumentation , composition rules and presentation style. From then on, music for small rooms was intended for soft instruments with a differentiated presentation style; the increasing harmony developed especially in this area. Music for large rooms with strong reverberation used loud instruments and was simply seated.

Music room from the 17th and 18th centuries

If music was intended for “use”, with a liturgical function, as entertainment or representation music , it was played in rooms that were actually intended for other purposes. It was only with music that was played and heard for its own sake that this music got its own space. Until the late Middle Ages , secular music was played in private houses, in rooms that were otherwise used for living, sleeping or working.

For the first time, the palaces of the Renaissance princes had the room types salon for representative music performance and chamber for listening to art enjoyment. Paolo Corteses De cardinalatu (1510) first asked the cardinals of the Curia to take into account a cubiculum musicae when furnishing their palaces . H. a room for making music after the meal. The first example documented around 1530 is an octagonal room in the Odeon of the philosopher Alvise Cornaro in Padua . The nobles also set up music rooms in castles , manors and city palaces north of the Alps . They differ neither architecturally nor acoustically from the other rooms. Musical scenes in painting or stucco often indicated the function of these rooms; Well-known examples from the 18th century can be found in the Berlin and Potsdam City Palace , in Sanssouci and in the New Palace . The allocation of the music room and concert room initially remained fluid, as both private music making and music performances always took place in small groups.

Up until that time, concerts were only performed within the same social class in private or semi-public settings. It was only in the course of the 18th century that the public-commercial concert system, which emerged in England at the end of the 17th century , was established, which in the subsequent period would eventually displace private concerts. Various room types were used as event locations. At the royal courts these were banqueting and ballrooms, in private households living rooms ; Club rooms, salons, churches, coffee houses and restaurants were the first public venues and offered space for the musical academies .

The first public concerts, held in London in 1672 , were purely for entertainment. The audience listened to music while they smoked, drank, and discussed. Thomas Mace , in his Musick's Monument (1676), advocated setting up public concert halls in response. The musicians should sit in the middle of the hall, the listeners in the surrounding galleries . Tubes were designed as a means of sound for the rear seats. The seating arrangements of the musicians who turned their backs on the audience at that time was still based entirely on chamber music practice and the style of performance of the Renaissance. Public concerts became so popular and economically successful in London that numerous halls were built within a century. The best known were the York Building (1675), Hickford's Room (1697), Carlisle House (1690), where Johann Christian Bach and Christian Ferdinand Abel held the first subscription concerts in history, Almack’s Great Room (1768), the Pantheon (1772) and finally the Hanover Square Rooms (1773), for which Joseph Haydn composed the London symphonies . The Holywell Music Room (1748), built in Oxford after the model of London, is the oldest surviving concert hall in the world that is still used.

The concert halls of that time only held a few hundred listeners. They were built on a rectangular floor plan, had a raised stage on one narrow side of the hall and sometimes vaulted ceilings. Thanks to its short reverberation time and low bass amplification , the sound was clear and audible. Fixed seating was not yet available; the halls were multifunctional, they were also used for festive events and masked balls . The Pleasure Gardens were founded as the first open-air spaces for an audience from all social classes . There were more than 60 of them in London alone. Here, too, listeners walked up and down during the concerts or sat under the roof of a pavilion .

On the European continent, the first concert halls in the German area incurred, in Hamburg the Concert Hall on the Kamp (1761) and in Leipzig , the first building of the Gewandhaus (1781) on the upper floor of the old armory . The Leipzig Hall became the model for many other halls in the 19th century, when the culturally interested bourgeoisie needed places to maintain musical life. The majority of the concert halls until then were rooms that served other purposes, theaters, redoubt and ballrooms.

Concert halls in the 19th century

When the concert industry became a permanent feature of musical life in the 19th century, the number of concert halls skyrocketed. The development of the symphonic with its enlargement of the orchestral apparatus and the increasingly differentiated timbres , which required improved acoustics, also changed the appearance of the halls, which now had to offer an average of 1,500 listeners.

The most widespread was the rectangular box hall type based on the model of the old Gewandhaus. It had a narrow floor plan, i. H. small width in relation to the length, a high ceiling, a parquet floor at ground level , a stage podium and a surrounding, narrow gallery. Fixed seating for continuous gaming had already established itself. The good acoustic properties of these halls resulted from the combination of fullness of sound on the one hand - a reverberation time of one and a half to two seconds became common - and on the other hand a large volume with a relatively small sound absorption surface . Since the halls were built narrow, the strong lateral sound reflection favored the clarity of the sound. The most important rooms are the Great Hall of the Wiener Musikverein (1870), the New Gewandhaus in Leipzig (1884) and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw (1888).

From the 20th century

Modern architecture shaped economic considerations - concert halls often have to be able to accommodate more than 2,500 listeners - and new structural engineering options. For the first time, large cantilever balconies could be built into the room. The technical means of sound measurement led to precise scientific knowledge in room and building acoustics . There was also a tendency towards individual architectural design.

The concert halls appeared in many different types of construction. There are sometimes halls with several balconies such as Carnegie Hall in New York City , the Orchestra Hall in Chicago and the now destroyed Queen's Hall in London. Important works of experimental architecture in the shape of a funnel with a rising ceiling or an asymmetrical floor plan were the theater in Essen and the Finlandia Hall in Helsinki , two works by Alvar Aalto . The parquet of these types of construction has been increasing in general since then. As early as 1838, John Scott Russell had transferred the laws of fluid mechanics known from shipbuilding to acoustics and defined the "isoacoustic curve", i.e. H. the curve of the same acoustic properties within a room. His calculations were implemented in the Auditorium Building in Chicago in 1889 .

The Royal Festival Hall in London, completed in 1951, was the first concert hall to be built based on acoustic calculations. Since the 1960s, halls with variable acoustics have become increasingly popular; these are able to offer different types of music - chamber music, orchestral concerts, solo performances, etc. - the appropriate performance conditions in each case, so that they can be played with different types of programs throughout. The Espace de projection (1978) at the Paris IRCAM allows both the room volume and the reverberation time to be changed in a ratio of 1: 4. Since the late 1980s, a larger number of rectangular box halls has been recorded among the new buildings.

The Berlin Philharmonie , which was built by Hans Scharoun and inaugurated on October 15, 1963, was also designed according to the laws of acoustics. The building is asymmetrical and tent-like with a pentagonal large concert hall. The seats offer an equally good view of the stage in the middle from all sides thanks to the irregularly rising box terraces. This leads to room acoustics problems, which have been solved so well with a special wall construction and bulging fabric surfaces on the ceiling that you can enjoy excellent acoustics in all seats. The architecture largely eliminates the separation between artist and audience. Artists appreciate sitting “in the middle” of the audience at the Philharmonie, who in turn can observe the actors from all sides depending on where they are seated.

Because of its peculiar, circus-like design with the concert podium in the middle, the Philharmonie was also jokingly called Circus Karajani in Berlin , in reference to Herbert von Karajan, the long-time chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic (see Sarrasani Circus ).

proof

literature

- Christoph Metzger : Music and Architecture . Edited on behalf of the International Music Institute Darmstadt. Pfau, Saarbrücken 2003, ISBN 3-89727-227-X .

- Christoph Metzger: Sensualistic Architectures by Frank Lloyd Wright, Tadao Ando and Ieoh Ming Pei , in: Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, 127jh., 5, 2011, p. 34f

- Helga de la Motte-Haber : Music and fine arts. From tone painting to sound sculpture . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 1990, ISBN 3-89007-196-1 .

- The music in the past and present . General encyclopedia of music, founded by Friedrich Blume. Second, revised edition published by Ludwig Finscher . Bärenreiter, Kassel / Basel / London / New York / Prague and JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1998. Article Musik und Architektur , Sachteil Vol. 6, Spp. 729-745.

- Christoph Metzger: "Architecture and Resonance", JOVIS Verlag Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-86859-270-2

further reading

- Michael Forsyth : Buildings for Music. The architect, the musician and the listener from the seventeenth century to the present day . Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT-Press 1985. ISBN 0-262-06089-2

- Werner Heinz : Music in Architecture. From antiquity to the Middle Ages . Frankfurt am Main: Lang 2005. ISBN 3-631-54427-8

- Christoph Metzger : Architecture and Response . Berlin, Jovis 2015. ISBN 978-3-86859-270-2

- Luise Nerlich : SOUND tectonics | Design grammar in architecture and music , Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-86068-476-4

- Rudolf Wittkower : Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism . Warburg Institute (University of London) 1971

- Iannis Xenakis : Musique. Architecture . Tournai: Casterman 1976

Web links

- Architecture and music - harmony and proportion - extensive representation of the references.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Motte-Haber p. 22

- ↑ Motte-Haber p. 23

- ↑ Motte-Haber p. 24

- ^ Ernst Kurth: Basics of the linear counterpoint. Introduction to the style and technique of Bach's melodic polyphony . Bern: Drechsel 1917. p. 209

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 729 f.

- ↑ Vitruvius 1, 1, 8–9.

- ↑ Christian Berger, Measure and Sound. The design of the tonal space in early occidental polyphony (PDF; 455 kB), cf. also MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 730 f.

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 731f.

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 734-736

- ↑ Grete Wehmeyer: Erik Satie . Reinbek: Rowohlt 1998, p. 144 f.

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 737-740

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Col. 740

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Col. 741

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 741-743

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Col. 743

- ↑ MGG-S, Vol. 6, Spp. 743 f.