1st symphony (Mahler)

The 1st Symphony in D major is a symphony by Gustav Mahler . He temporarily gave the work the nickname Titan , but later withdrew the title.

Emergence

The symphony was written in Leipzig between January and March 1888. The preliminary work, however, goes back to 1884. Mahler took the suggestion for the symphony from his first song cycle, the songs of a traveling journeyman from 1885.

Mahler was initially unsure whether he should conceive the work as a symphonic poem or as a symphony . The originally planned division of the sentences into two parts fell over the course of time, as did an additional sentence originally in the second position. This is occasionally still listed under the name Blumine . During the first performances, Mahler also tried to make it easier for the audience to access the work by giving the work and movement titles. The title Titan , which is occasionally added, refers to the novel of the same name by Jean Paul . Mahler later withdrew this programmatic name. The funeral march was briefly nicknamed A Funeral March in Callot's manner , which was an allusion to ETA Hoffmann's fantasy pieces in Callot 's manner . However, Mahler did not even know this work at the time the symphony was written, so that the title, which has also been withdrawn, is probably based on the suggestion of his friend Ferdinand Pfohl .

In 1889 Mahler performed the work in Budapest as a symphonic poem in two parts. Mahler even wrote a fully elaborated program for the Hamburg performance in 1893, which he later refrained from adding, "because I saw the wrong ways the audience got there". It was only when it went to press in 1899 that the symphony was given its four-movement form, which is still known today.

To the music

Orchestral line-up

4 flutes (3 and 4 also piccolo ), 4 oboe (3rd also English horn ), 4 clarinets (3rd also bass clarinet and clarinet, 4. clarinet and A clarinet, in the fourth set, doubled) 3 Bassoon (3rd also contrabassoon ), 7 horns , 5 trumpets , 4 trombones , 1 bass tuba , timpani (two players), percussion (triangle, cymbals, tam-tam, bass drum), harp , first violin , second violin, viola , Violoncello , double bass

1st movement: slowly. Dragging. Like a natural sound - very leisurely in the beginning

The first movement has the form of a strongly varied sonata main movement . In the introduction, which is over 60 bars in length, the musical events emerge extremely cautiously and carefully. An organ point on A in seven octaves forms the basis on which various “natural sounds” appear as fragmentary scraps of motifs. For example, the striking falling fourth, which functions as the original motif for the entire work.

After this long, slow introduction, the exposition begins , which only unfolds a single theme that Mahler has borrowed from his song Ging this morning over the field from the cycle of songs of a traveling journeyman . The carefree singing wandered piano various orchestral parts. This theme appears again in a modified form in the final movement. The subsequent implementation deals with motives from the introduction rather than from the exposition. The focus here is on the contrast between the slow introduction and the moving main theme. At the end of the development, the fragmentary natural sounds in the introduction appear again, introducing a shortened recapitulation . Towards the end of the movement, the main theme of the final movement becomes clearer, but has not yet been formulated. Instead, a jubilant coda begins , which is derived from a motif in the introduction.

2nd movement: Strongly moved, but not too fast

The second movement is made up of a rough countryman who takes up elements of Austrian folk music . The sentence is clearly structured and is more conventional. It begins with the original motif of the falling fourth in the accompaniment of the low strings. The country theme, on the other hand, takes up elements of the main theme from the first sentence. The trio offers lyrical material in contrast to the Länders. It begins with a horn motif, whereupon an enthusiastic country melody develops in the strings. This is replaced in the second part of the trio by a cantable waltz by the cellos . Towards the end of this trio there is thematic material from the first movement. The movement closes with a repetition of the Ländler, in a more concise form and with a slightly larger orchestration.

3rd movement: Solemn and measured without dragging

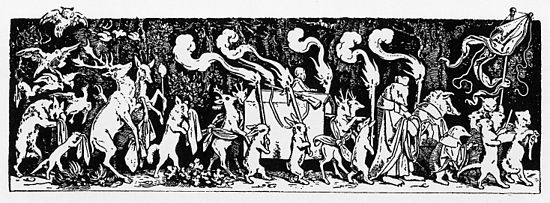

The third movement in D minor begins with an arrangement of the folk song canon “ Frère Jacques ”, alienated into a funeral march . Mahler takes up the minor version of the canon sung in parts of Austria. The musical action increases slowly from the beginning of the movement and has the effect of an approaching funeral procession. The character of the funeral march, however, seems grotesque and ironic. The melody seems empty and hard. A sudden change of mood is brought about by klezmer-like motifs from the Jewish music world used by Mahler in the first trio . In this sentence there are always strong opposites next to each other, as is typical of Mahler's style of composition. The lyrical middle section in the form of the second trio quotes the “Lindenbaum” passage from Mahler's own song The Two Blue Eyes of My Sweetheart from the songs of a traveling journeyman . The dream remains only a short episode, and with an abrupt shift to E flat minor, the funeral march returns. This fades away in the eerie pizzicato of the basses in pianissimo .

4th movement: Stormily moved

The final movement is also based on a strongly varied sonata main movement form. While in the first movement the "going out" into nature and in the broadest sense the development of music is discussed, the final movement describes the opposite. Only after several breakthroughs does the symphony's apotheosis take place . The motifs sound rushed and aggressive at first, the music piles up again and again and seems almost chaotic. The movement begins with a wildly moving motif of the whole orchestra in the utmost hectic and dynamic . From this develops the main, the hero theme in F minor, which was already indicated in the first movement. Only after a while does the action calm down, and a lyrical and extremely intimate, distantly reminiscent of Bruckner 's second theme in D flat major establishes itself. The implementation begins with the return of the main theme, which is processed using hectic and fragmentary motifs. For the first time, the main theme is heard, turned extremely cautiously in pianissimo to major. A wave of growth sets in to sing the theme cheerfully in C major. The chorale-like expansion of the theme also appears in full for the first time. The recapitulation begins with the lyrical second theme in a different form. Then the main theme sounds in its minor form. This is done in preparation for the final apotheosis in the form of a large wave of increases. The liberating final breakthrough to D major is laboriously achieved in a long process. This takes place under the greatest tension of the whole orchestra. With the solemn sound of the chorale in the brass section in D major, the apotheosis is finally brought about. In most symphonic performances, the horn players play the final theme in a standing position in order to drown out the large symphony orchestra, which is already large in the late Romantic period. The hymn-like jubilant tutti song ends the symphony.

effect

The first performance of the 1st symphony took place on November 20, 1889 under the direction of the composer as a symphonic poem in Budapest . At that time Mahler was the director of the Royal Hungarian Opera there. The performance was met with extremely divided opinions, ranging from enthusiasm to indignation and malice. The writer Karl Kraus reported that the audience was split up into “Mahler friends and Mahler haters” who fought “a fierce battle”. The Mahler friends had to calm down malicious laughs from the Mahler opponents. “In the noise of the party struggle, nothing more could be heard of the strange orchestral sounds”. The New Pest Journal certified Mahler as his famous conductors colleagues to be "no Symphony". The Hungarian music magazine Pesti Hírlap celebrated the first three movements and only criticized the finale of the symphony. The actual premiere of the work in its final form as a pure symphony took place on March 16, 1896 in Berlin . The important music critic Eduard Hanslick , who had already regularly panned Anton Bruckner's symphonies , formulated his criticism based on the “horror finale”. He postulated that the “new symphony belongs to the genre of music that for me is not”. Hanslick wished he could better understand Mahler's intentions for the puzzling procedure, but also testified to the enthusiastic applause of the mainly young audience. The excitement surrounding the strange-sounding new symphony is hardly understandable from today's perspective, since the 1st symphony is one of the most classic and romantic works in the Mahlerian symphonies. It is played with pleasure and often today and is considered to be the forerunner of Mahler's even more important, later symphonies.

Status

The 1st symphony already contains many typical elements of Mahler's musical language. The use of folk melodies, the ironic alienation, the collage-like layering of motifs and the sometimes harsh processing of the themes are alluded to here. The grotesque, coarse rhythms of the Scherzo also recur more and more strongly in the following works. The juxtaposition of the apparently unsuitable, as Mahler conceives in the third movement, later becomes the rule in the 3rd and 4th symphonies . Mahler also uses the conception of the final movement, which leads to apotheosis with several breakthroughs , in many later symphonies. In the 6th symphony there will even be a collapse. In none of these symphonies does the final apotheosis occur with comparable clarity. Nevertheless, Mahler established a model in his first work that became binding for his future work: the conception of the work towards a redeeming finale. "All Mahler's symphonies are final symphonies" remarked Paul Bekker as early as 1921. This debut work is still very close to the classical-romantic type of symphony in the traditional Beethoven - Brahms / Bruckner line . This can be seen, for example, in the classic four movements and the orchestral line-up, which is moderate by Mahler's standards. Only in the 4th and 9th symphonies will the cast be smaller. In these symphonies, this step is combined with a radical simplification in order to leave musical conventions behind. In the 1st symphony, however, the late Romantic pathos can still be heard, from which Mahler only finally breaks free in the 4th symphony . In terms of sound, Mahler's first work also prepares new paths at best, but without actually treading them. The expansion of chromatics and tonality to their limits, which was characteristic of Mahler later , as it is pursued more and more consistently from the 5th symphony at the latest , hardly takes place here. Nevertheless, the work sounds already late-romantic progressive.

literature

- Paul Bekker: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies. Berlin 1921 / Reproduced Tutzing 1969.

- Ferdinand Pfohl: Gustav Mahler, impressions and memories from the Hamburg years. Edited by Knud Martner . Karl Dieter Wagner, Hamburg 1973, pp. 64–67.

- Herta Blaukopf : Gustav Mahler - Letters. Extended and revised new edition, Vienna 1982.

- Constantin Floros : Gustav Mahler III, The Symphonies. Wiesbaden 1985.

- Alphons Silbermann : Lübbes Mahler Lexicon . Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1986, ISBN 3-404-61271-X .

- Reinhold Weyer: Gustav Mahler: 1st Symphony. In: S. Helm, H. Hopf (Hrsg.): Work analysis in examples. Gustav Bosse, Regensburg 1986, ISBN 3-7649-2276-1 , pp. 245-265.

- Mathias Hansen: Reclam's music guide Gustav Mahler. Reclam, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-15-010425-4 .

- Ute Jung-Kaiser : The true images and codes of “tragic irony” in Mahler's “First”. In: Günther Weiß (Ed.): Neue Mahleriana: essays in honor of Henry-Louis de LaGrange on his seventieth birthday . Lang, Berne etc. 1997, ISBN 3-906756-95-5 , pp. 101-152.

- Renate Ulm (Ed.): Gustav Mahler's Symphonies. Origin - interpretation - effect. Bärenreiter, Kassel 2001, ISBN 3-423-30827-3 .

- Stefan Hanheide: Mahler's visions of doom. epOs-Music, Osnabrück 2004, ISBN 978-3-923486-60-1 .

- Gerd Indorf: Mahler's symphonies . Rombach, Freiburg i. Br./Berlin/Wien 2010, ISBN 978-3-7930-9622-1 .

Web links

- Discography (french)

- 1st Symphony (Mahler) : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Discussion of the 3rd movement with "listening task" (lesson minutes in the advanced music course at the Celtis-Gymnasium Schweinfurt)

- Gerhard Müller: Blumine. (PDF, 140 kB)

- Jeffrey Gantz. Gustav Mahler's Blumine: A Love Story. The Phoenix Archives. Sept. 28, 2000 (PDF)

- Jeffrey Gantz: Missing Movement? The provenance of Blumine in Mahler's First Symphony. 2006 ( Memento from June 10, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF, English; 85 kB)

Audio files

- Computer- generated recordings by the Virtual Philharmonic Orchestra (Reinhold Behringer), created using digital instrumental samples.

Spring and no end - first movement of the 1st symphony by Gustav Mahler.

With full sails - second movement of the 1st symphony by Gustav Mahler.

Stranded - The hunter's funeral - Third movement of the 1st symphony by Gustav Mahler.

Dall'Inferno al Paradiso - fourth movement of the 1st symphony by Gustav Mahler.

Blumine - Original second movement of the 1st Symphony by Gustav Mahler - here with live trumpet play (Julius Eiweck).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Vera Baur: A great organic becoming . In: Renate Ulm: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies, 58f.

- ↑ The originally planned movements therefore had the names: Spring and no end , Blumine , With full sails , Stranded and Dall'Inferno . In addition: Constantin Floros: Gustav Mahler III, 25f.

- ^ Letter to Friedrich Löhr. Quoted from: Herta Blaukopf: Briefe, 147.

- ↑ Vera Baur: A great organic becoming . In: Renate Ulm: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies , 64.

- ↑ Karl Kraus : Article in Die Fackel , November 1900, No. 59, 26f. In: Renate Ulm: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies, 69.

- ↑ Victor von Herzfeld: Article in Neues Pest Journal , November 21, 1889. Quoted from: Kurt Blaukopf 1976, 186. In: Renate Ulm: Gustav Mahler's Symphonie, 68.

- ↑ Kornél Hirlap: Article in Pesti Hirlap , November 21, 1889. Quoted from: Kurt Blaukopf 1976, 186. In: Renate Ulm: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies, 68.

- ^ Eduard Hanslick : Article in New Free Press , November 20, 1900. In: Renate Ulm: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies, 70.

- ^ Paul Bekker: Gustav Mahler's Symphonies, 20.