Ancient Greek medicine

The first known Greek medical school was founded around 550 BC. . Chr in the southern Italian Croton opened where Alcmaeon of Croton taught the author of the first anatomical work ; this is where the practice of patient observation was established. The ancient Greek medicine focused mainly on the humoral or four-juice teachings . The most important role in ancient Greek medicine was played by the doctor Hippocrates of Kos , the most famous representative of the medical school in Kos . Hippocrates and his students documented their experiences in writing, later summarized in the Corpus Hippocraticum , which also contains the Hippocratic oath . The Greek Galenus was one of the most important surgeons of antiquity , who underwent numerous daring operations, including brain and eye operations. The writings of Hippocrates, Galen, and others had a lasting influence on medieval European and Islamic medicine until numerous views were dismissed as outdated in the 14th century.

Early influences

Despite their well-known high esteem for Egyptian medicine , attempts to demonstrate a concrete influence on Greek medicine were not particularly successful due to a lack of sources and problems in understanding the ancient medical terminology . It is certain, however, that the Greeks listed substances imported from Egypt in their pharmacopoeias ; this influence continued to grow after the establishment of a Greek medical school in Alexandria .

Hippocrates and Hippocratic Medicine

The outstanding personality of the Greek medical history was the doctor Hippocrates of Kos (460-370 BC), the "father of modern medicine". The Corpus Hippocraticum contains a collection of around seventy early medical works from ancient Greece that are closely related to Hippocrates and his disciples. Hippocrates is best known as the author of the Hippocratic oath, which is still important to doctors today.

The existence of the Hippocratic Oath indicates that this "Hippocratic" medicine was practiced by a group of professional doctors who were bound by a strict ethical code. Prospective students usually paid a fee for the training and entered into a family relationship with their teacher. The training included oral instruction by the teacher and also practical assignments as his assistant, since the oath assumed that the student and patient would enter into a relationship with one another. The oath also set limits to medical action (“ I will not give anyone a deadly poison ”) and even refers to the existence of another group of medical specialists, such as the surgeons (“ I will ... leave that to the men who practice this trade. "). Hippocratic medicine, the most lasting achievement of which is the development of medical ethics, is considered the basis for medicine as an independent science. The basis for the physiology within the Hippocratic medicine, the humoral pathology is a study of the (four) humors. How Alcmaeon , Parmenides and Empedocles took the Hippocratic physicians in contrast to Aristotle, that in the procreation both sexual partners "seed" shares contribute.

Hippocrates and his students were the first to describe numerous diseases and ailments. They recognized the drumstick fingers as an important diagnostic sign for chronic purulent lung diseases, lung cancer or heart diseases . Hence, these fingers were sometimes called "Hippocratic fingers". Hippocrates was also the first doctor to describe the Hippocratic face in Prognosis .

Hippocrates began by categorizing the course of the disease into acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and used terms such as " irritation , relapse , anti-inflammatory , crisis , attack , or convalescence ". Another essential contribution of Hippocrates is the description of the symptoms of physical findings, the surgical treatment and prognosis of pleural empyema , ie the suppuration within the chest cavity. His teachings in areas such as pulmonary medicine and surgery remain of lasting importance.

The Corpus Hippocraticum contains the central medical texts of this school. Today the authorship is ascribed to a number of authors who lived several decades before Hippocrates. A direct assignment of certain writings to the authorship of Hippocrates is difficult.

Asklepieia

Sanctuaries, which were dedicated to the god of healing Asklepios , as Asklepieia , served as centers for medical advice, oracles, and therapy. In these sanctuaries the patient was put into a trance-like sleep state, enkoimesis (ενκοίμησις), not unlike anesthesia, during which he was healed either under the guidance of the deity in a dream ( enkoimesis ) or through an operation. The Asklepieia had specially equipped rooms in which healing was accompanied and promoted. In the Asclepion of Epidaurus , there are three large marble slabs dating from 350 BC. The names, ailments, patient histories, and treatment of approximately 70 patients who recovered in the sanctuary. The descriptions of surgical operations such as the opening of abdominal abscesses or the removal of traumatic foreign bodies, in which the patient was put into a state of enkoimesis by means of anesthetic substances such as opium , appear credible because of their realism.

Aristotle

The Greek philosopher Aristotle was the most influential scholar of the ancient world . Although his early works on natural philosophy were speculative, his later biological writings were based on empiricism , biological causality and the diversity of habitats . Aristotle thought nothing of the experiment , but assumed that the terms showed their true nature in their own - instead of in a controlled artificial - environment. While this view was not conducive to physics and chemistry , it remained so to zoology and behavioral studies , where the work of Aristotle retained "real meaning". He made countless observations of nature, especially the habits and properties of the flora and fauna , to which he devoted great attention to his categorization . In total , Aristotle identified 540 animal species and dissected at least 50.

According to Aristotle, all natural processes were guided by spiritual ends and the causa formalis . From such a teleological point of view, Aristotle saw his observations as evidence of this formal design. He said that nature would not give any animal horns or tusks on a whim, but only give them these possibilities as necessary. In a similar way, Aristotle saw the creatures in a gradation of perfection, ascending from plants to humans: the scala naturae or great chain of being .

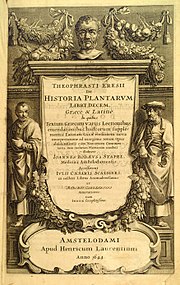

According to Aristotle, the perfection of a creature is expressed in its respective form and is not predetermined by the form. Another aspect of his biology was the threefold division of the soul: a vegetative soul for reproduction and growth, a sensitive soul for movement and sensation and a sensible soul for thinking and reflecting. Plants only had the first part, animals had the first two, and humans had all three. In contrast to earlier philosophers and the Egyptians, Aristotle assigned the rational soul a place in the heart rather than in the brain. Noteworthy is Aristotle's division of sensation and thought, which - with the exception of Alkmaion of Croton - was directed against the earlier philosophers. Theophrastus of Eresos , the successor of Aristotle at Lycaion , wrote a series of botanical works - including the history of plants - which survived the Middle Ages as the most important contribution of antiquity to botany . Many of Theophrastus' names have survived to this day, such as carpos for fruit and pericarpion for seed capsule. Instead of referring to formal reasons, like Aristotle, Theophrastus created a mechanistic scheme, showing analogies between natural and artificial processes, referring to Aristotle's concept of causa efficiens . Theophrastus also recognized the importance of sexuality for the reproduction of some higher plants, although this last discovery was lost in later times. The biological-teleological ideas of Aristotle and Theophrasts, as well as their emphasis on a number of axioms in place of empirical observation, cannot simply be separated from their implications for Western medicine.

Alexandria

After Theophrastus' († 286 BC) work, the Lykaion no longer produced an independent work. Although the interest in Aristotle's ideas persisted, these were usually adopted without question. It was not until the age of Alexandria under the Ptolemies that advances in biology were made again. The first medical teacher in Alexandria, Herophilus of Chalcedon , corrected Aristotle by localizing intelligence in the brain and establishing a connection of the nervous system with movement and sensation. Herophilos also distinguished between veins and arteries and demonstrated the pulse in the latter through experiments with live pigs. In the same direction he developed a diagnostic technique that determined different types of pulse. Like his contemporary Erasistratos von Chios , he explored the role of the veins and nerve pathways across the body.

Erasistratos registered the connection between the higher complexity of the human brain surface and higher intelligence compared to animals. He repeatedly experimented with a captured bird and documented its weight loss between feeding times. According to his teacher's pneumatic research, he claimed that the human circulatory system is controlled by a vacuum that pulls blood through the body. The air absorbed into the body would be sucked from the lungs into the heart, converted there into spirit and then pumped through the arteries throughout the body. Part of this spirit of life reaches the brain , where it is converted into sensual spirit and then distributed through the nerves. Herophilos and Erasistratos carried out their experiments on convicted prisoners of their Ptolemaic kings alive , and “observed, as long as the body was breathing, the parts that nature had previously hidden, observing their position, color, shape, size, arrangement, hardness , Examined softness, smoothness and bond ”.

Although some Greek atomists, such as Lucretius, opposed the teleological view of Aristotelian ideas about life, teleology (and, after the rise of Christianity, natural theology ) continued to be a central point of biological thought until the 18th and 19th centuries.

In the words of Ernst Mayr :

“No impact on biology according to Lucretius and Galen until the Renaissance. Aristotle's ideas of natural history and medicine survived, but were usually adopted without question. "

Historical legacy

Through longer contact with Greek culture and the eventual conquest of Greece, the Romans adopted numerous Greek medical ideas. Early Roman responses to Greek medicine ranged from enthusiasm to rejection, but eventually the Romans found a positive view of Hippocratic medicine.

This acceptance led to the spread of Greek medical theories throughout the Roman Empire, and thus much of the West. The most influential scholar who continued and expanded the Hippocratic tradition was Galenus († approx. 207). However, all Hippocratic and Galenic texts were lost in the early Middle Ages after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the Latin West , but in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) they were further studied and followed. After 750 AD, the Muslim Arabs in particular translated Galen's works and later adopted the Hippocratic-Galenic tradition until they finally expanded it on their own under the special influence of Avicenna . From the end of the 11th century, the Hippocratic-Galenic tradition returned to the Latin West with numerous Arabic translations and some original Greek texts. During the Renaissance , translations of Galen and Hippocrates were made directly from Greek from newly accessible Byzantine manuscripts . So great was Galen's influence that even after Western Europeans began dissecting in the 13th century, scholars often pressed into the Galen model their findings that Galen might have questioned. The anatomical texts and pictures of Andreas Vesalius , however, led to a significant improvement in the Galenic anatomy. William Harvey's account of the circulatory system was arguably the first real blow to Galen's misconception about the circulatory system. Nevertheless, despite its ineffectiveness and extreme danger, the Hippocratic-galenic practice of bloodletting continued into the 19th century. The Hippocratic Galenic tradition was only really replaced when the microscope-based studies by Louis Pasteur , Robert Koch and others showed that diseases are not caused by an imbalance of the four humors, but by microorganisms such as bacteria.

See also

Remarks

- ↑ Atlas of Anatomy, ed. Giunti Editorial Group, Taj Books LTD 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Heinrich von Staden: Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, pp. 1-26.

- ↑ PC Grammaticos, A. Diamantis: Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus. In: Hellenic journal of nuclear medicine. Volume 11, Number 1, 2008 Jan-Apr, pp. 2-4, ISSN 1790-5427 . PMID 18392218 .

- ^ The father of modern medicine: the first research of the physical factor of tetanus , European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

- ^ Hippocrates: The "Greek Miracle" in Medicine

- ↑ The Father of Modern Medicine: Hippocrates ( Memento of February 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Pedro Laín Entralgo : La medicina hipocrática. Madrid 1970.

- ^ Owsei Temkin, What Does the Hippocratic Oath Say? . In: "On Second Thought" and Other Essays in the History of Medicine . Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2002, pp. 21-28.

- ↑ Jutta Kollesch , Diethard Nickel : Ancient healing art. Selected texts from the medical writings of the Greeks and Romans. Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1979 (= Reclams Universal Library. Volume 771); 6th edition ibid. 1989, ISBN 3-379-00411-1 , pp. 16 and 19-27.

- ^ Robert A. Schwartz, Gregory M. Richards, Supriya Goyal: Clubbing of the Nails . WebMD, accessed September 28, 2006

- ^ Charles Singer , E. Ashworth Underwood: A Short History of Medicine. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1962, p. 40

- ^ Roberto Margotta: The Story of Medicine. Golden Press, New York 1968, p. 70.

- ↑ Fielding H. Garrison: History of Medicine. WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia 1966, p. 97.

- ^ Félix Martí-Ibáñez: A Prelude to Medical History MD Publications, Inc., New York 1961, p. 90.

- ↑ Vivian Nutton: Ancient Medicine . Routledge, London - New York 2004.

- ^ A b Guenter B. Risse: Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals . Oxford University Press, New York 1999, ISBN 0-19-505523-3 , pp. 56 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ A b José Carlos Diz, Avelino Franco, Douglas R. Bacon, J. Ruprecht, Julián Alvarez: The History of Anesthesia . Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on the History of Anesthesia, Santiago, Spain, September 19-23, 2001. Elsevier, Boston 2002, ISBN 0-444-51293-4 , pp. 11-17 ( limited preview in the Google book search - chapter Surgical cures by sleep induction as the Asclepieion of Epidaurus by Helen Askitopoulou, Eleni Konsolaki, Ioanna A. Ramoutsaki and Maria Anastassaki).

- ^ Mason, A History of the Sciences p. 41

- ^ Annas, Classical Greek Philosophy, p. 247

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought , pp. 84-90, 135; Mason, A History of the Sciences , pp. 41-44

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought , pp. 201-202; see also: Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being

- ↑ Aristotle, De Anima II 3 ( Faculty of the Soul )

- ^ Mason, A History of the Sciences, p. 45

- ^ Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy Vol. 1 p. 348

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought , pp. 90-91; Mason, A History of the Sciences , p. 46

- ^ Annas, Classical Greek Philosophy p. 252

- ^ Mason, A History of the Sciences, p. 56

- ^ Barnes, Hellenistic Philosophy and Science p. 383

- ^ Mason, A History of the Sciences , p. 57

- ↑ Barnes, Hellenistic Philosophy and Science , pp. 383-384

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought , pp 90-94; Quote on p. 91.

- ^ Annas, Classical Greek Philosophy , p. 252

- ↑ von Staden, Liminal Perils: Early Roman Receptions of Greek Medicine. In: F. Jamil Ragep, Sally P. Ragep with Steven Livesey: Tradition, Transmission, Transformation . Brill, Leiden 1996, pp. 369-418.

literature

- Julia Annas: Classical Greek Philosophy . In: John Boardman , Jasper Griffin , Oswyn Murray (Eds.): The Oxford History of the Classical World . Oxford University Press, New York 1986, ISBN 0-19-872112-9 .

- Jonathan Barnes: Hellenistic Philosophy and Science . In: John Boardman , Jasper Griffin, Oswyn Murray (Eds.): The Oxford History of the Classical World . Oxford University Press, New York 1986, ISBN 0-19-872112-9 .

- Louis Cohn-Haft: The Public Physicians of Ancient Greece . Northampton, Massachusetts, 1956.

- William KCGuthrie : A History of Greek Philosophy. Volume I: The earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans . Cambridge University Press, New York 1962, ISBN 0-521-29420-7 .

- William HS Jones: Philosophy and Medicine in Ancient Greece . Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore 1946.

- James Lennox: Aristotle's Biology . In: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . February 15, 2006. Retrieved October 28, 2006.

- James Longrigg: Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcmæon to the Alexandrians . Routledge, London - New York 1993.

- Arthur O. Lovejoy : The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea . Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 1936. Reprinted by Harper & Row, ISBN 0-674-36150-4 , 2005 Paperback: ISBN 0-674-36153-9 .

- Stephen F. Mason: A History of the Sciences . Collier Books, New York 1956.

- Ernst Mayr : The Growth of Biological Thought: Diversity, Evolution, and Inheritance . The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass.) 1982, ISBN 0-674-36445-7 .

- Gilbert Médioni: The Greek medicine according to Hippocrates. In: Illustrated History of Medicine. German arrangement by Richard Toellner et al., (Six-volume) special edition Salzburg 1986, Volume I, pp. 350–393.

- Heinrich Rohlfs : About the spirit of the Hippocratic medicine. In: German Archive for the History of Medicin u. medicinische Geographie 4, 1881 (reprinted Hildesheim and New York 1971), pp. 3-61.

- Renate Scheiper: Medicine in antiquity before and after Hippocrates. In: Physis. Medicine and Natural Sciences Volume 8, 1992, No. 8, pp. 12-22.

- Heinrich von Staden (Ed.): Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge - New York 1989, ISBN 0521236460 Google Book .

- Jerry Stannard: Hippocratic pharmacology. In: Bulletin of the History of Medicine 35, 1961, pp. 497-518.

- Karl Sudhoff : Medical information from Greek papyrus documents. Building blocks for a medical cultural history of Hellenism. Leipzig 1909 (= studies on the history of medicine , 5).