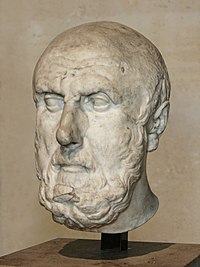

Arkesilaos

Arkesilaos ( Greek Ἀρκεσίλαος Arkesílaos , other form of the name Ἀρκεσίλας Arkesílas ; * around 315 BC; † 241/240 BC in Athens ) was an ancient Greek philosopher . He is also called Arkesilaos of Pitane after his hometown . He lived in Athens and belonged to the Platonic Academy , which he directed as a scholarch for decades and which he gave a new direction. With him began the era of the later so called younger (“skeptical”) academy, which is also (less appropriately) called “middle academy”.

His philosophy is based on the experience of aporia (hopelessness), which plays a central role in some of Plato's dialogues . When persistent attempts to find definitive, irrefutable answers to philosophical questions have failed, an “aporetic” perplexity arises. Old apparent certainties have turned out to be questionable in the course of a philosophical investigation without it being possible to replace them with new certainties. From the generalization of such experiences and from a detailed analysis of the cognitive process, a fundamental doubt arises about the ability of the mind to produce reliable knowledge. Moreover, Arkesilaos believes that he can show that strong counter-arguments can be found for any philosophical statement. He therefore regards it as a requirement of honesty to generally abstain from judging, i.e. to refrain from formulating mere opinions as judgments with a claim to truth. He thus became the founder of skepticism within the Platonic Academy, which continued there into the early 1st century BC. The prevailing direction remains. Academic skepticism interacts with a similar non-academic current, pyrrhonism ("pyrrhonic skepticism").

swell

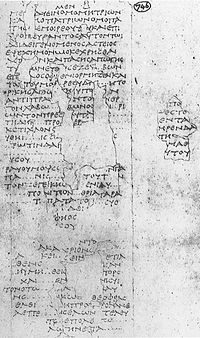

The main biographical sources are the biography of Arkesilaos in the doxographer Diogenes Laertios and a report in the Academica (Academicorum index) of Philodemos . Both representations contain material from a lost biographical description of Antigonus of Karystos , who was a younger contemporary of Arkesilaos. Philodemus probably knew the work of Antigonus directly, while Diogenes Laertios obtained his knowledge from there indirectly from a likewise lost intermediate source. We owe important information about the teaching to Sextus Empiricus . There are also excerpts from a lost work by the Middle Platonist Numenios , which the church father Eusebios of Caesarea passed on in his Praeparatio evangelica ; However, this is a distorted representation from the opponent's point of view. Much more information comes from Cicero , some from Plutarch . Often the sources only refer to the academic skeptics in general terms, but research has inferred from the context that this also or primarily refers to Arkesilaos.

Life

Arkesilaos came from the city of Pitane in the Aiolis on the northwest coast of Asia Minor . His father Seuthes had a Thracian name. The family was wealthy. When his father died, he was still a minor. Therefore, he was placed under the guardianship of his half-brother Moireas. In his home country he received lessons from the astronomer and mathematician Autolykos von Pitane .

His guardian wanted him to be trained to be a speaker, but he preferred philosophy. With the support of another half-brother, he was able to get his way. He went to Athens to study. There the music theorist Xanthos and the mathematician Hipponikos were his teachers. He joined the peripatetic philosopher Theophrast , from whom he received more rhetorical than philosophical lessons. Later he was won over to the academy by the Platonist Krantor ; Theophrast regretted the gifted pupil's departure. From then on Arkesilaos was close friends with Krantor. After his death he published the writings left behind by the deceased. He attended the lessons of the scholastic Polemon and Krates and expressed his great admiration for these two philosophers. After the death of the Krates he took over the management of the academy between 268 and 264, after a philosopher named Sokratides, who had initially been elected to this office, had resigned.

In debates, Arkesilaos, like Socrates, pursued the goal of rejecting unjustified claims to knowledge. But he proceeded differently than the classic model. He renounced the Socratic irony and the confession of his own ignorance . Instead of the Socratic dialogue with questions and short answers, he usually chose an approach in which he first allowed the interlocutor to speak in detail, then went into his explanations and finally gave him the opportunity to reply. He was not satisfied with showing the other person the lack of rigor in his argument, following Socrates' example. Rather, he wanted to show the validity of his thesis, according to which there is a counter-thesis for every statement that can be justified with arguments of comparable weight, which means that one has to abstain from a decision.

Arkesilaos was generous and discreetly provided financial support to many in need. His extraordinary persuasiveness earned him numerous students, although he was also known as a sharp blasphemer and was prone to ridicule. His clear, precise thinking, his rhetorical and didactic skills, his humor and his quick-wittedness were recognized. On the well-disposed side, he was described as devoid of vanity, while opponents accused him of lust for fame. He encouraged his students to listen to other teachers outside the academy. Despite sharp factual contrasts with other schools, he treated their followers with respect; He did not allow his students to public personal polemics against them. When his student Baton , a comedy poet, attacked a representative of an opposing philosophical direction on the stage, he forbade him to attend his lectures and thus forced him to apologize.

He remained unmarried and had no children. His main patron was Eumenes I , the ruler of Pergamon , who generously supported him as a patron . He was close friends with Hierocles, the Macedonian commander of the port of Piraeus and the Munichia fortress there. As an envoy to Athens, he went to see King Antigonus Gonatas , but this trip was unsuccessful. Otherwise he stayed away from state affairs and spent most of his time in the academy.

Arkesilaos was not a proponent of asceticism , but devoted to physical enjoyment. As a result, opposing parties claimed that he died from excessive wine consumption that confused his mind. He was offended by his coexistence with hetaera , to which he openly confessed. In doing so, he referred to the principles of Aristippus of Cyrene , who had taken the view that luxury and also dealing with hetaerae were compatible with a philosophical way of life, as long as one did not make oneself dependent on it.

Apparently he ran the academy until his death in 241 or 240. His pupil Lakydes succeeded him.

Works

According to a claim communicated by Diogenes Laertios and also known to Plutarch , Arkesilaos did not write any writings. According to a contrary report, which Diogenes Laertios mentions in a different context, there were works by him, because it was claimed that he dedicated writings to Eumenes I in gratitude for generous gifts. In his youth he is said to have written a treatise on the poet Ion of Chios . Only two short poems reproduced by Diogenes Laertios and a letter to a relative concerning his will have survived. It is possible that before he became a scholarch, Arkesilaos wrote the Second Alcibiades , a pseudo-Platonic dialogue.

Teaching

Epistemological skepticism

In fact, Arkesilaos gave the academy a completely new direction, although he insisted that he was not an innovator and referred to Socrates and Plato , whose authentic philosophy he believed he represented. In doing so, he placed the main emphasis on the Socratic tradition. The starting point of his thinking was the Socratic question of the accessibility of secure knowledge. Like Socrates, he argued against foreign views with the aim of shaking certainties and showing that the alleged knowledge of the representatives of different beliefs is in reality based on unproven assumptions and that they are therefore mere opinions. However, he did not limit himself to unmasking supposed knowledge using the Socratic dialectic in individual cases as pseudo knowledge , but turned to the epistemological question of its origin. In doing so, he came to the conclusion that the claim to have acquired certain knowledge is in principle not verifiable, because the cognitive process is by its nature unsuitable as a way to a well-founded certainty. This can be shown for every conceivable assumption, because it is possible to cite such weighty counter-reasons against any assertion that an equilibrium arises and a decision is impossible. Therefore, the only appropriate attitude for a philosopher is to abstain (epochḗ) from judgment, to renounce the formulation of a doctrine. With this, Arkesilaos gave up the ontology traditionally cultivated in the academy and the philosophical striving for truth in general, with which he distanced himself from his teaching despite his admiration for Plato. His skepticism related not only to sensory perception, which Plato had already distrusted, but also to the possibility of knowledge about intelligibles such as the Platonic ideas .

Arkesilaos did not develop his own epistemology, because for such a doctrine he would have had to make a claim to truth that would have brought him into conflict with his own skepticism. Rather, he turned against the epistemology of the Stoics , a then new school of philosophy that rivaled the Academy. In dealing with the stoic theory of knowledge, he tried to use the model of the Stoics to show the inaccessibility of certain knowledge. The Stoics assumed that every process of cognition consists in the creation of an idea to which the cognizing individual then gives or refuses his consent. In addition to the knowledge that is only accessible to the wise, and the mere opinions of the foolish multitude, there is the "grasping" (katálēpsis) of a single state of affairs, which happens when one agrees to a reliable idea. The wise man can derive an inalienable, systematically ordered knowledge as an overall understanding from such observations, while the non-wise one is unable to develop his individual observations, which are already interspersed with opinions, into a realistic understanding of objective reality. But every single act of apprehension by a wise man or a non-wise man gives him access to a certain undoubtedly true state of affairs. On the other hand, Arkesilaos argued that a perception-mediating idea (katalēptikḗ phantasía) , to which one could ascribe reliability, could not be demonstrated. Such a concept, according to the Stoic definition, is when it is true and could not also be false. However, according to Arkesilaos' criticism, this property cannot be assigned to a single idea. There is no evidence for the stoic claim that some ideas are so evidently true that there is no room for doubt.

Arkesilaos underpinned his argument by giving many different ("colorful") considerations. Most of the anonymously handed down arguments and examples of the skeptical academics probably came from him. Among other things, it concerns the following considerations: Sensual cognition cannot provide certainty, since delusions, dreams, hallucinations and the extreme similarity of confusable similar things show the questionability of the naive belief in the reliability of sensory perceptions. For every correct idea that enables a correct perception of something real, there is a false one, indistinguishable from it, with which it can be confused (principle of aparallaxia). A clear demarcation of the reliable understanding from the unreliable opinion is impossible, since no objective criterion can be named for it. Every decision to declare an idea reliable from a certain level of assumed trustworthiness is as arbitrary as the decision to designate a number of cereal grains as a heap as soon as a certain number of grains is reached (" heap closure "). From this it can be seen that not only the naive, habitual perception proceeding from sensory perception is unsuitable for gaining knowledge, but that the process of concept formation must also be subjected to fundamental criticism because of its lack of precision. Such arguments were intended to expose the stoic concept of capture as an illusion.

Even in ancient times it was unclear how consistently Arkesilaos carried out his skepticism, and different views have been expressed about this in modern research. Cicero reports that he went beyond Socrates, who said he knew that he knew nothing; Arkesilaos did not even claim to be certain about his own ignorance. According to this, Arkesilaos included his own skeptical point of view in his skepticism and, with this most radical form of skeptical thinking, anticipated an objection by opponents that the skeptical doubt would cancel itself out. Whether Arkesilaos actually carried out “self-inclusion”, the application of skeptical criticism to oneself, is disputed in research. One hypothesis is that he did not subject the assumed superiority of his epistemological skepticism to the Stoic epistemology to skeptical doubt in the sense that he would have assumed a balance of contradicting views here too. Rather, he was of the opinion that it was a real issue. In contrast to the later skeptical scholar Karneades , who developed a theory of probability, Arkesilaos dispensed with probability statements, since he could not find a reliable differentiation criterion for them or for truth assertions.

The introduction of radical skepticism in the academy, which had previously been shaped by traditional doctrines, struck some ancient interpreters as so astonishing that they suspected a secret dogmatism behind it. There were rumors that Arkesilaos only displayed his skepticism in public, but that in the academy he presented his doctrines to a narrower group of students considered worthy as assertions of truth. Even in modern research it has often been suspected that Arkesilaos was looking for truth and that he believed he could get closer to it. The skepticism was not a fundamental conviction, but was intended to lead into the aporia for a didactic purpose and ultimately, as with Socrates, served the search for a higher truth; in addition, it was used as a weapon in the dispute with the Stoics. According to the current state of research, however, it can be assumed that Arkesilaos actually represented a consistent skepticism out of conviction and contemporaries like the Stoic Chrysippos rightly understood it that way.

Sextus Empiricus , a representative of Pyrrhonism going back to Pyrrhon von Elis , a radical skepticism, expressly appreciates the proximity of the position of Arkesilaos to his and emphasizes the similarities. Otherwise, however, he distances himself from academic skepticism, which he does not consider to be real skepticism and therefore does not call it that. He claims that academic skepticism differs from Pyrrhonic in that it declares a reliable apprehension of a truth to be impossible in principle, while the Pyrrhonians take a less dogmatic, i.e. more consistently skeptical standpoint, according to which the possibility that the apprehension of truth succeeds is not fundamentally excluded can. This seems to contradict Cicero's statement that Arkesilaos also included his own position in his turning away from any dogmatism. However, since Sextus does not name Arkesilaos among the academics, whose skepticism he considers to be relatively dogmatic and therefore inadequate, he evidently does not count him in this group. He separates him from the other academics and brings him close to Pyrrhonism. Therefore there is no contradiction to Cicero's statement and no need to assume Arkesilaos to be lacking in consistency on this point.

The radical skepticism regarding human access to secure knowledge does not exclude such knowledge from a divine authority. Arkesilaos is said to have believed that the deity hid the truth from people. Whether he wanted to express a religious creed is doubtful; he can hardly have developed a theological doctrine, since his skepticism offered no basis for it.

ethics

For Arkesilaos, skepticism also has an ethical dimension. Although he rejects the claim that knowledge about the absolutely good can be obtained, and jokingly remarks that he has never seen anything good, he sees something ethically desirable and precisely in the renunciation of categorizing individual processes or circumstances as good or bad Valuable. Since evaluative judgments lead to emotions that are detrimental to peace of mind, abstaining from them is ethically desirable from his point of view. Here, too, as Sextus Empiricus states, his position agrees with that of Pyrrhonic skepticism. However, Sextus considers the Pyrrhonic formulation, according to which abstention from judgment only appears as a moral good, to be more consistently skeptical than that of the Arkesilaos, which implies an alleged knowledge that abstention really (pros tēn phýsin) is a good. It is uncertain whether Arkesilaos actually formulated it as apodictically as Sextus suggests; Sextus may be based on a doxographic tradition, which dogmatically reproduced the cautious statements of Arkesilaos and thus falsified them.

It is unclear how Arkesilaos solved the difficult problem of developing a theory of action compatible with the principle of abstention. Critics argued that any act requires the consent of the agent. Those who abstain from judging in principle cannot make a decision and carry it out and are therefore condemned to inaction (apraxía) . As Sextus Empiricus reports, Arkesilaos described the “well-founded” (to eúlogon) as a guideline for what is desirable or avoidable. He considered an act to be ethically well founded if it can be reasonably justified after it has been carried out. If one adheres to the well-founded, happiness ( eudaimonia ) will arise .

Various interpretations have been suggested for this in research. One approach emphasizes that what is well-founded only proves to be such after the act, i.e. no prior knowledge is expected from the agent. However, this does not solve the problem that the agent then initially follows a mere opinion instead of philosophically correct abstaining from the judgment, and seems to gain knowledge afterwards. According to another interpretation, Arkesilaos relaxed the requirement of abstention from judgment in ethics; With the use of the term “the well-founded” he wanted to avoid the hopelessness of a complete lack of decision criteria. According to a third proposed explanation, he did not advocate the doctrine of the well-founded as his own conviction, but only discussed it as a hypothesis in the context of his discussion with the Stoics. A fourth interpretation can be inferred from discussions by Plutarch, who responded to criticism of academic skepticism. It says that Arkesilaos does not consider an action to be well founded because the actor agrees to it on the basis of a knowledge that he has at his disposal. Rather, the well-foundedness is given for him when the acting person follows a natural impulse that leads him to the beneficial (oikeíon) and makes it appear to him as well-founded. Seen in this way, it is a matter of well-foundedness not from the perspective of a human assessor who could prove the well-foundedness of his actions or omissions, but from the point of view of nature, which controls human behavior. A weakness of this position, which did not escape the stoic critics, is that in this case one acts without reasonable consideration, because the beneficial is instinctively recognized. If human reason is not involved in such actions, it is dethroned as the directing authority. This contradicts the conventional ancient - also Platonic - understanding of philosophical life.

The unfavorable source situation does not allow a clear clarification of the question. After all, according to the current state of research, it can be assumed that nature, which makes what is beneficial to man appear to be well founded, played a central role in Arkesilaos as a normative, action-guiding authority. In doing so, he probably assumed an understanding of the relationship between nature and human activity that he had got to know from his teachers Polemon and Krantor.

Relationship to other philosophy schools

Arkesilaos fought the views of Stoics and Epicureans and was in turn attacked by supporters of rival philosophy schools. Kolotes von Lampsakos, a pupil of Epicurus , polemicized against him. The prominent Stoic Chrysippos wrote writings against his doctrine, one of which was entitled Gegen das Methödchen des Arkesilaos (with “Methödchen” perhaps a relevant work by the criticized was meant).

Another contemporary, the skeptic Timon , criticized Arkesilaos in his Silloi , a work in which he mocked numerous philosophers. Later, however, Timon wrote a book Funeral Supper for Arkesilaos in which he paid him tribute. Timon, like the stoic Ariston of Chios , who had temporarily studied with Arkesilaos with Polemon, that the teaching of Pyrrhons of Elis, the founder of the "Pyrrhonic" skepticism, had an effect on Arkesilaos. Timon's initial criticism of Arkesilaos is probably due to the fact that he wanted to belittle academic skepticism as an unoriginal imitation of the Pyrrhonic, his own direction.

The conspicuous similarities between academic and Pyrrhonic skepticism, which Sextus Empiricus later emphasized, make the assumption of an influence appear plausible, and Diogenes Laertios reports that Arkesilaos admired Pyrrhon. The influence of Pyrrhons on Arkesilaos is difficult to prove in detail and is discussed controversially in research. One difference is the attitude towards the existence of objective truth. In view of the impenetrability of the phenomena, the Pyrrhones even doubted that terms such as “true” and “false” could be meaningfully related to statements about things in the outside world. Arkesilaos and the academic skeptics who followed him, on the other hand, demanded abstention from judgment in the face of human ignorance, but nevertheless considered the statements about external reality to be necessarily objectively true or false. They only denied that the correctness or incorrectness of such a statement can be determined in individual cases, since there are no criteria for determining the truthfulness.

In his confrontation with the Stoics, Arkesilaos used stoic terms - some of which were, however, of older origin - and started from stoic concepts such as “consent” to an emerging idea. Whether he did this exclusively for the purpose of argumentation and refutation or granted the stoic premises a certain justification and usefulness is disputed in scholarship; the research literature on this is extensive. Because of his occasional participation in Theophrast's classes, an influence of peripatetic thinking on his philosophy has been suggested. It is noticeable that the skeptical academics, although sharply opposed stoic and Epicurean doctrines, never polemicizes against the Peripatos. So far, however, it has not been possible to make the presumed peripatetic influence on Arkesilaos specifically plausible.

reception

Antiquity

The disciples of Arkesilaos included Apelles of Chios, Apollonios of Megalopolis , Arideikas of Rhodes, the comedian Baton, Demophanes of Megalopolis, Demosthenes of Megalopolis, Dionysius of Colophon, Dorotheos of Amisos , Dorotheos of Thelphusa, Ekdemos of Megydesalopolis, who was his successor as Scholarch, Panaretus, Pythodoros, Telekles of Metapont and Zophyros of Colophon. Also Eratosthenes , who later became a famous scholar, attended his classes and expressed his appreciation for him. The Stoic Chrysippos, who later emerged as an opponent of his philosophy, also attended his lectures. The "Younger Academy" initiated by him remained until its end in the 1st century BC. Basically true to his skeptical attitude, but changed it considerably, especially with the introduction of probabilistic considerations.

The stoic Ariston of Chios , a contemporary of Arkesilaos, accused him - modifying a verse of Homer - that he was in the front Plato, in the back Pyrrhon (from Elis) and in the middle Diodorus . By this Ariston meant that the philosophy of his opponent was based on a failed eclecticism , a monstrous combination of disparate elements. Arkesilaos is only “in front”, that is supposedly or apparently, a Platonist. The Pyrrhonian Timon von Phleius made a similar accusation - albeit from a completely different perspective . He claimed that Arkesilaos, as a Platonist, was originally a dogmatist, but as such had suffered argumentatively shipwrecked and then saved himself by swimming to Pyrrhon and Diodorus, that is, found refuge in skepticism.

Cicero valued Arkesilaos, considered him to be an authentic heir to Socraticism and saw in his skepticism a legitimate expression of Platonism , the emphasis on a certain aspect of the Socratic-Platonic tradition. "Dogmatic" Platonists came to a completely different assessment after in the 1st century BC. A counter-movement to academic skepticism and a return to the principle of judgments and doctrines had started. Middle Platonists like Antiochus of Askalon and Numenios saw in Arkesilaos an innovator who had fallen away from Platonism and destroyed the Platonic tradition.

The church fathers Laktanz and Eusebios of Caesarea dealt with Arkesilaos as part of their discussion of Greek philosophy. Eusebios considered the efforts of the skeptical academic to be fruitless, Laktanz accused him of being self-refuting.

Modern

Modern research strives for a balanced assessment of the personality and role of the founder of academic skepticism in the history of philosophy. Walter Burkert believes that Arkesilaos brought a breath of fresh air into the school debates, which "benefited true philosophy and prevented premature solidification and even aging". Anthony Long emphasizes that his appearance prevented Hellenistic philosophy from sliding into obscurity, dogmatism and fruitless speculation. Woldemar Görler agrees and notes that the criticism of the Arkesilaos was also beneficial to his stoic opponents. But he also points out that the academic skepticism was exhausted in the mere refutation of opposing claims and that it was hardly in a position to put something new and constructive in the place of the teachings it opposed. Arkesilaos' ability to respect those who think differently and not turn factual differences of opinion into personal conflicts is recognized. The flexibility of the school that Plato founded shows that such an unconventional and uncomfortable thinker as he was able to assert himself as head of the academy and give it a new direction.

Source editions and translations

- Heinrich Dörrie (Ed.): The Platonism in antiquity , Volume 1: The historical roots of Platonism . Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1987, ISBN 3-7728-1153-1 , pp. 136–169, 387–433 (source texts with translation and commentary)

- Konrad Gaiser (Ed.): Philodems Academica . Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1988, ISBN 3-7728-0971-5 , pp. 129-133, 261-266, 536-545

- Hugh Lloyd-Jones , Peter Parsons (Eds.): Supplementum Hellenisticum . De Gruyter, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-11-008171-7 , pp. 42–43 (No. 121 and 122: Gedichte des Arkesilaos), 80 (No. 204), 379–380 (No. 805-808), 387 (No. 829); Supplementary volume: Hugh Lloyd-Jones (Ed.): Supplementum supplementi Hellenistici . De Gruyter, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-11-018537-7 , p. 12 f. (No. 121 and 122)

- Anthony A. Long , David N. Sedley (Eds.): The Hellenistic Philosophers. Texts and comments . Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01574-2 , pp. 523-549 (translation of source texts with comments)

- Hans Joachim Mette : Two academics today: Krantor from Soloi and Arkesilaos from Pitane . In: Lustrum 26, 1984, pp. 7–94 (compilation of the source texts)

- Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane. L'origine del platonismo neoaccademico (= philosophy hellénistique et romaine , 1). Brepols, Turnhout 2016, ISBN 978-2-503-55029-9 , pp. 149-273 (compilation of the source texts with Italian translation)

literature

- Tiziano Dorandi : Arcésilas de Pitane . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 1, CNRS, Paris 1989, ISBN 2-222-04042-6 , pp. 326-330

- Woldemar Görler : Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4: The Hellenistic Philosophy , 2nd half volume, Schwabe, Basel 1994, ISBN 3-7965-0930-4 , pp. 786–828

- Anna Maria Ioppolo: Opinione e scienza. Il dibattito tra Stoici e Accademici nel III e nel II secolo a. C. Bibliopolis, Napoli 1986, ISBN 88-7088-137-7

- Malcolm Schofield : Academic epistemology . In: Keimpe Algra u. a. (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-61670-6 , pp. 323-351

- Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane. L'origine del platonismo neoaccademico (= philosophy hellénistique et romaine , 1). Brepols, Turnhout 2016, ISBN 978-2-503-55029-9

Web links

- Charles Brittain: Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Diogenes Laertios: Arkesilaos (English translation by Robert Drew Hicks)

- Diogenes Laertios: Αρκεσίλαος (original text from Wikisource )

Remarks

- ↑ A brief overview of the sources is given by Woldemar Görler: Älterer Pyrrhonismus. Younger academy. Antiochus from Ascalon. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 775-989, here: 775 f., 786 f. See Tiziano Dorandi: Arcésilas de Pitane . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 1, Paris 1989, pp. 326-330, here: 327 f.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Mette: Two academics today: Crane from Soloi and Arkesilaos from Pitane . In: Lustrum 26, 1984, pp. 7-94, here: 78.

- ^ Anthony A. Long: Diogenes Laertius, Life of Arcesilaus . In: Elenchos 7, 1986, pp. 429-449, here: 440; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 788.

- ↑ For the details of the change of office see Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 791 f.

- ↑ Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, p. 20. Cf. the different opinions of Charles E. Snyder: The Socratic Benevolence of Arcesilaus' Dialectic. In: Ancient Philosophy 34, 2014, pp. 341–363 and Anna Maria Ioppolo: Elenchos socratico e genesi della strategia argomentativa dell'Accademia scettica. In: Michael Erler , Jan Erik Heßler (eds.): Argument and literary form in ancient philosophy , Berlin 2013, pp. 355–369, here: 364–367.

- ↑ On Baton's relationship to Arkesilaos see Italo Gallo: Teatro ellenistico minore , Rome 1981, pp. 19–26.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Mette: Two academics today: Crane from Soloi and Arkesilaos from Pitane . In: Lustrum 26, 1984, pp. 7-94, here: 81, 83; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 794 f.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 795 f .; Hans Joachim Mette: Two academics today: Krantor from Soloi and Arkesilaos from Pitane . In: Lustrum 26, 1984, pp. 7-94, here: 86 f.

- ↑ Tiziano Dorandi: Ricerche sulla cronologia dei filosofi ellenistici , Stuttgart 1991, pp. 7-10 has suggested that Lakydes may have been a scholarch as early as 244/243; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 795 f., 830 f. agrees and proposes as a declaration that Arkesilaos left the official business at least partially to Lakydes three years before his death. Dorandi later gave up his hypothesis; see Dorandi: Chronology , in: Keimpe Algra u. a. (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy , Cambridge 2005, pp. 31–54, here: 32.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 4.32 and 4.38; for the interpretation of the relevant tradition see Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 786 f., Anthony A. Long: Diogenes Laertius, Life of Arcesilaus . In: Elenchos 7, 1986, pp. 429-449, here: 431 f.

- ↑ See also Marcello Gigante: Poesia e critica letteraria in Arcesilao . In: Luigi de Rosa (ed.): Ricerche storiche ed economiche in memoria di Corrado Barbagallo , Vol. 1, Napoli 1970, pp. 429-441, here: 439-441. However, it cannot be ruled out that it is not the poet but Plato's Dialogue Ion that is meant.

- ↑ See also Peter von der Mühll : The poems of the philosopher Arkesilaos . In: Studi in onore di Ugo Enrico Paoli , Firenze 1956, pp. 717-724; Marcello Gigante: Poesia e critica letteraria in Arcesilao . In: Luigi de Rosa (ed.): Ricerche storiche ed economiche in memoria di Corrado Barbagallo , Vol. 1, Napoli 1970, pp. 429–441, here: 431–439.

- ↑ This is one of Aldo Magris' hypotheses: The “Second Alcibiades”, a turning point in the history of the Academy . In: Grazer Contributions 18, 1992, pp. 47–64.

- ↑ On Arkesilaos' reception of Socrates and Plato see Julia Annas : Platon le skeptique . In: Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 95, 1990, pp. 267-291; Carlos Lévy: Plato, Arcésilas, Carnéade. Response to J. Annas . In: Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 95, 1990, pp. 293-306; John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy , Göttingen 1978, pp. 35-47; Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, pp. 82–88.

- ↑ Anna Maria Ioppolo: elenchos socratico e genesi della strategia argomentativa dell'Accademia scettica. In: Michael Erler, Jan Erik Heßler (eds.): Argument and literary form in ancient philosophy , Berlin 2013, pp. 355–369, here: 358–364.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 796–801.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 805 f. See the considerations of Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, pp. 133–135.

- ↑ On his approach see Hans Joachim Krämer : Platonismus und Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, pp. 37–47; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 796–801.

- ↑ On this technical term and the problem of its translation see Peter Steinmetz : Die Stoa . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 491–716, here: 529–532 and Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 798–800.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 798–800; Hans Joachim Mette: Two academics today: Krantor from Soloi and Arkesilaos from Pitane . In: Lustrum 26, 1984, pp. 7-94, here: 89 f.

- ^ Sextus Empiricus: Adversus mathematicos 7,154.

- ↑ On the different views of stoics and academics about the indistinguishability of correct and incorrect impressions see Michael Frede : Stoic epistemology . In: Keimpe Algra u. a. (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy , Cambridge 2005, pp. 295–322, here: 309–313.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 800 f .; on the cluster, see also Walter Burkert: Cicero as a Platonist and a Skeptic . In: Gymnasium 72, 1965, pp. 175-200, here: 191.

- ^ Cicero, Academica 1.45.

- ↑ See also Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 802. Cf. Hans Joachim Krämer: Platonismus und Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, pp. 54, 104–106 and note. 419

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 802; Malcolm Schofield: Academic epistemology . In: Keimpe Algra u. a. (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy , Cambridge 2005, pp. 323–351, here: 325–327; Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Krämer: Platonism and Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, p. 56 and note 213; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 802.

- ^ See on this John Glucker: Antiochus and the Late Academy , Göttingen 1978, pp. 296-306; Hans Joachim Krämer: Platonism and Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, p. 54 f .; Carlos Lévy: Skepticisme et dogmatisme dans l'Académie: "l'ésotérisme" d'Arcésilas . In: Revue des Études Latines 56, 1979, pp. 335-348. John Dillon : The Heirs of Plato , Oxford 2003, p. 237 sees the motivation behind this creation of legends in a need to be able to maintain a consistent continuity for the academic tradition.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 801–806; Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, pp. 47–49, 56–58.

- ↑ Anna Maria Ioppolo: La testimonianza di Sesto Empirico sull'Accademia scettica , Napoli 2009, pp. 29-35, 42 f.

- ^ This is how John M. Cooper argues: Arcesilaus: Socratic and Skeptic . In: Lindsay Judson, Vassilis Karasmanis (ed.): Remembering Socrates , Oxford 2006, pp. 169–187, here: 183–186.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 811, 823 f .; see. Hans Joachim Krämer: Platonism and Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, p. 52 f.

- ↑ On the question of Sextus' Arkesilaos interpretation and on his sources, see Anna Maria Ioppolo: La testimonianza di Sesto Empirico sull'Accademia scettica , Napoli 2009, pp. 45–52.

- ↑ See Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, pp. 61–69, 74 f., 135.

- ↑ Anna Maria Ioppolo: Opinione e Scienza. Il dibattito tra Stoici e Accademici nel III e nel II secolo a. C. , Napoli 1986, pp. 160 f.

- ↑ In this sense, some researchers believe that they can interpret the well-founded as an element of the Arkesilaos' own practice-related doctrine, with which his skepticism appears less radical; see Anna Maria Ioppolo: Il concetto di "eulogon" nella filosofia di Arcesilao . In: Gabriele Giannantoni (ed.): Lo scetticismo antico , Vol. 1, Napoli 1981, pp. 143-161; Margherita Lancia: Arcesilao e Bione di Boristene . In: Gabriele Giannantoni (ed.): Lo scetticismo antico , Vol. 1, Napoli 1981, pp. 163–177, here: p. 177 and note 33.

- ↑ This opinion is, for example, Gisela Striker : Skeptical Strategies . In: Malcolm Schofield et al. a. (Ed.): Doubt and Dogmatism. Studies in Hellenistic Epistemology , Oxford 1980, pp. 54–83, here: 64–66.

- ↑ On Plutarch's remarks, see Anna Maria Ioppolo: Su alcune recenti interpretazioni dello scetticismo dell'Accademia . In: Elenchos 21, 2000, pp. 333-360.

- ↑ In this sense u. a. Franco Trabattoni: Arcesilao platonico? In: Mauro Bonazzi, Vincenza Celluprica (ed.): L'eredità platonica. Studi sul platonismo da Arcesilao a Proclo , Napoli 2005, pp. 13-50.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 810.

- ↑ Anna Maria Ioppolo: Opinione e Scienza. Il dibattito tra Stoici e Accademici nel III e nel II secolo a. C. , Napoli 1986, pp. 137-146; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 810 f.

- ↑ Anna Maria Ioppolo: Opinione e Scienza. Il dibattito tra Stoici e Accademici nel III e nel II secolo a. C. , Napoli 1986, pp. 146-152.

- ↑ For details see Paul A. Vander Waerdt: Colotes and the Epicurean Refutation of Skepticism . In: Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 30, 1989, pp. 225-267.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 786; Hans Joachim Mette: Two academics today: Krantor from Soloi and Arkesilaos from Pitane . In: Lustrum 26, 1984, pp. 7-94, here: 85.

- ^ Jacques Brunschwig: Introduction: the beginnings of Hellenistic epistemology . In: Keimpe Algra u. a. (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy , Cambridge 2005, pp. 229-259, here: 250.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 790, 812–815.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Krämer: Platonism and Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, pp. 6–8, 11–13; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 819 f.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 7,183 f.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 4.33. Cf. Anna Maria Ioppolo: Elenchos socratico e genesi della strategia argomentativa dell'Accademia scettica. In: Michael Erler, Jan Erik Heßler (eds.): Argument and literary form in ancient philosophy , Berlin 2013, pp. 355–369, here: 356; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 811 f.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 812; Michael Lurie: The shipwrecked Odysseus or: How Arkesilaos became a skeptic. In: Philologus 158, 2014, pp. 183–186.

- ↑ See on Cicero's assessment Orazio Cappello: The School of Doubt , Leiden 2019, pp. 129, 133, 136–138, 171 f.

- ↑ See the references in Simone Vezzoli: Arcesilao di Pitane , Turnhout 2016, pp. 229–243.

- ^ Walter Burkert: Cicero as a Platonist and a skeptic . In: Gymnasium 72, 1965, pp. 175–200, here: 189.

- ^ Anthony A. Long: Diogenes Laertius, Life of Arcesilaus . In: Elenchos 7, 1986, pp. 429-449, here: 431.

- ^ Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 805 f., 824.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : Hellenistic Athens and her Philosophers , Princeton 1988, p. 6 describes him as a "model gentleman"; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 794 agrees.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Krämer: Platonism and Hellenistic Philosophy , Berlin 1971, pp. 35 f., 53; Woldemar Görler: Arkesilaos . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. Die Philosophie der Antike , Vol. 4, 2nd half volume, Basel 1994, pp. 786–828, here: 824.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Arkesilaos |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Arkesilaos of Pitane; Arkesilas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Greek philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 315 BC Chr. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | uncertain: Pitane , Aiolis |

| DATE OF DEATH | 241 BC BC or 240 BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Athens |