Library of Pergamon

The Pergamon Library was one of the most important ancient libraries . It was located in the Greek city of Pergamon , today's Bergama in Turkey . It was founded around 200 BC. BC, the time of their end is unclear and possibly falls in the 1st century BC. There is little information about the library of Pergamon that can be found in ancient literary sources. In the early 1880s, remains of buildings were uncovered, which, according to a majority, but controversial view among researchers, are the remains of the library.

Nothing is known precisely about their size. It can be assumed, however, that it was a nationally important library that possibly held around 200,000 scrolls . In ancient texts a library catalog is mentioned, in which the scrolls in the library were listed. The catalog itself has not been preserved.

The library was built during the Hellenistic period and was located in one of the most important cities of this period. Pergamon was the capital of the Pergamene Empire . Like the other Hellenistic libraries, this one was built and operated by rulers. It probably served representative purposes as part of the Attalids' cultural policy and, like the library of Alexandria, was located in the immediate vicinity of the royal palaces. If the remains are actually the library, then it was part of the Athena sanctuary , which, like other important buildings, was located on Pergamon's castle hill .

Lore

The written information on the library of Pergamon is extremely sparse. There are around 15 text passages by ancient authors, whereby the library is often only mentioned briefly. Two stone inscriptions found at the gymnasium of Pergamon , on which a library is mentioned, probably do not refer to the library of Pergamon, but to a school library located in the gymnasium.

excavation

location

The remains of the library are on the plateau of Pergamon Castle Hill, on which numerous important buildings stood. Important sanctuaries and the palaces of kings were located in the vicinity of the library. On the slopes and at the foot of the mountain, the residential districts of the city joined.

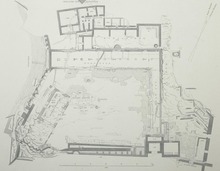

The oldest temple in the city, the Temple of Athena, was located within this narrow high plateau . It was surrounded on three sides by two-story porticoed halls that were built at a later date, and on the fourth side was the Pergamon Theater below the steep slope secured with retaining walls. The colonnaded halls and the courtyard, in which there were not only the temple but also statue monuments, formed the sanctuary of Athena. The library rooms were directly connected to the north of the porticoed halls of the sanctuary, through whose upper floor they were also entered. Rocks are located below the library rooms and directly adjacent to the basement of the portico.

remains

The Athena sanctuary was uncovered by German archaeologists shortly after 1880. The library consisted of a large hall measuring 16.95 × 13.53 m and three smaller rooms of different sizes, each about 90 square meters. Partly intact wall remains from the trachyte rock in Pergamon have been preserved from the great hall .

In addition to the remains of the wall, a one meter wide and 50 centimeter high layer of stone was found. It ran along three walls about half a meter away. It is believed that wooden shelves for the scrolls were placed on this stone foundation. In front of the eastern parts of the foundation, a narrow water channel hewn into the rock has been preserved for unknown purposes, including two extensions for pouring or skimming. In the southeast corner a cistern was found carved deep into the rock . In the middle of the foundation section to the north, its width doubles over a length of around 2.70 meters. Holes in the walls may have been used to attach shelves.

Since athena statues are mentioned in sources as library jewelry, the find of a 3.10 meter replica of Athena Parthenos is particularly worth mentioning. It was found two meters above the floor in the rubble of the great hall and could have stood on the ledge of the foundation to the north of the hall. Furthermore, there were smaller statues and cover plates, which possibly formed housings, which could have contained statuettes or scrolls.

On the doorway through which one entered the sanctuary of Athena, there were ornaments that show owls as well as other motifs. Occasionally they are interpreted as symbols for the library.

organization

Inventory size, acquisition of scrolls and library catalog

Today we can only guess at the number of scrolls. One source mentions 200,000 scrolls from Pergamene libraries. Marcus Antonius is said to have them in the 30s of the 1st century BC. Around 100 years after the incorporation of Pergamon into the Roman Empire, to Cleopatra VII and the Alexandrian library. This story is generally considered a legend, but allows conclusions to be drawn about the size of the population. In general, research judges that a stock of 200,000 rolls is a conceivable size for an ancient library. The largest ancient library, that of Alexandria, is said to have had 400,000 to 500,000 scrolls.

It has been handed down from the Pergamener acquisition policy that attempts were made to buy particularly old writings. Accordingly, scrolls up to 300 years old, individual papyri and labeled lime wood have been collected and stored in Pergamon . It is also reported that scriptures were sought throughout the empire to help build the library. Due to the aggressive acquisition policy, the library of Aristotle , which was then located in the city of Skepticism, was hidden underground by its private owners. A comment by the doctor Galenus could indicate a gift to the library. He reports that he left his books in Pergamon when he moved to Rome.

The size of the library made systems of order necessary, which made it possible to choose a desired work from the masses or to find the available literature on a particular topic. There are three explicit source references for a library catalog of the library of Pergamon. A document is reported that it was listed in the directories (pinakes) of Pergamon as the work of a Kallikrates, and of a speech by Demosthenes that it was entered in the directories of Alexandria and Pergamon under the title About the taxation classes. A third mention of the catalog can be found by the speaker and writer Athenaios .

Staff, library users and maintenance providers

The library staff is largely unknown. Presumably, as in Alexandria, they were well-known scholars who were closely related to the ruling house. Only the philosopher Athenodoros Kordylion is attested as the head of the library . Another report suggests that the philosopher and grammarian Krates von Mallos was also employed at the library, or at least was in close contact with it. It can be assumed that the library was primarily used by the scientists based in Pergamon. In addition to the two named, for example, the biographer Antigonos von Karystos , the mathematician Apollonios von Perge , the author of a paper on war machines Biton and Polemon von Ilion , who wrote country descriptions. As in Alexandria, older texts were collected and reissued in Pergamon. The Pergamene philologists also used incomprehensible passages from the old texts when compiling their texts, while the Alexandrians tended to correct or omit such passages.

Whether the royal library was open to the public , as Vitruvius claims, is debatable in research. It should be noted that only a small part of the population was literate and that scrolls were expensive.

The building of the library and the expensive collection of scrolls were financed by the rulers of the Pergamene Empire. Establishment and maintenance were part of a larger, lively cultural policy of the kings. The library was located in the immediate vicinity of the royal quarter (basileia) of the city to the east .

history

It is not clear which ruler founded the library. Possibly it was already Attalus I who visited Pergamon from 241 to 197 BC. Ruled. However, the geographer Strabo names Attalos' son and successor Eumenes II as the founder. Possibly the father arranged for an initial collection of scrolls while the son had his own library built and organized the business.

According to ancient reports, there was competition between the libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria. Accordingly, the rulers of both empires rivaled in the expensive acquisition of as many scrolls as possible. This competition turned the book trade into a lucrative business and resulted in negligently made copies and forgeries being produced and sold to the libraries. The rivalry is said to have gone so far that the Ptolemaic king forbade the export of the most important writing material , papyrus , from Egypt. Pergamon reacted to this with the invention of the writing material parchment , which is historically certainly wrong, since parchment was used long before. It is possible, however, that parchment production in Pergamon was improved or at least increased. Another source reports the same rivalry that two scholars were involved in. As a token of their acceptance of Roman supremacy, King Ptolemy and the grammarian Aristarchus sent papyrus as a gift to Rome. According to the report, their pergamene counterparts Attalos and Krates von Mallos then outperformed the two Egyptians by sending particularly well-made parchment to Rome.

In 133 BC The Romans inherited the Pergamene Empire. Neither the written sources nor the archaeological findings provide any information about the end of the library. Nonetheless, individual researchers have suggested that wealthy Romans may have read the scrolls in the 1st century BC. They were brought to Rome in the 4th century BC, also that the inventory was carried away to the Imperial Library of Constantinople in the 4th century or that it fell victim to the destruction of Pagan cultural assets under Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century.

Research history

In addition to a few representations of the sparse literary sources and the archaeological finds, the ancient scholarly examination of the subject is largely limited to the discussion of the archaeological question of whether the building remains found on the Acropolis really include the Pergamon library mentioned by ancient authors. Immediately after the excavations, Alexander Conze and Richard Bohn were of this opinion, which has largely dominated to this day, but has also provoked energetic opposition.

Conze and Bohn

The building complex was uncovered by Alexander Conze and Richard Bohn in the early 1880s, and the scientific results were published in 1885. Conze was the first to see the Pergamon library named in the literary sources in the four rooms, and Bohn shared this view. They assumed that the holes had lugs attached to support boards or wooden shelves. This device led the archaeologists to conclude that the hall was used as a storage room. It was also considered that the shelves should stand on the stone dais. They explained the distance between the walls and the podium, including the shelves, by saying that the shelves could be separated from the possibly damp walls. The fact that it was a storage room for books also resulted from the discovery of the Athena statue, as such statues were associated with libraries by some ancient authors. The analysis of found inscriptions, statues and cover plates, which were interpreted as housings for statuettes, provided further arguments for their thesis. A comparison with other ancient library buildings also made it seem plausible to Conze and Bohn that the findings were a library.

The further debate

The librarian and philologist Karl Dziatzko dealt with the question of whether all four rooms actually belong to a library in his 1897 contribution to Paulys Realencyclopadie der classical antiquity . He was critical of Conzes and Bohn's interpretation, but did not expressly reject them. Bernt Götze similarly assessed the interpretation in 1937 as plausible, but still uncertain. In 1944 Christian Callmer modified the original interpretation of Conze and Bohn again - as Dziatzko and Götze had done before. He assumed that the great hall was not used to set up shelves for scrolls, but was a meeting and festival room. The scrolls were stored in the three adjoining rooms. Similar views were represented by Carl Wendel in 1949 , Doris Pinkwart in 1976, Elzbieta Makowiecka in 1978 and Volker M. Strocka in 1981 .

Lora Lee Johnson spoke out against an interpretation as a library in 1984 and saw an exhibition room for statues in the main room. The archaeologist Harald Mielsch assumed in 1995 that the literarily attested library of Pergamon was in the gymnasium of Pergamon, where two inscriptions were found on which a library is mentioned. He saw no evidence of localization in the Athena sanctuary and interpreted the remains of the building there, similar to Johnson, as the treasury of the sanctuary, whose great hall housed a museum-like art collection with statues.

In the same year Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck expressed the opinion that a copy of the library catalog had been attached to the holes in the wall. In 2000, Volker M. Strocka took another stand and reinterpreted the main room as a dining room. The foundations could therefore have borne Klinen . One defender of the original interpretation as a library of Pergamon is Wolfram Hoepfner, who published on the subject in 1996 and 2002. He contradicted the representatives of the contrary opinion, but modified his interpretation in 2002 to the effect that the holes did not support book shelves but were used to fasten water channels. A subsequent use of the library hall as a dining room seemed plausible to him at a later time.

swell

- Jenö Platthy: Sources on the Earliest Greek Libraries with the Testimonia. Hakkert, Amsterdam 1968, pp. 159-165.

literature

Reference works and overview presentations

- Karl Dziatzko : Libraries . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume III, 1, Stuttgart 1897, Col. 405-424 (Section VI: Pergamenische Bibliothek ).

- Otto Mazal : Greco-Roman antiquity ( history of book culture , volume 1). Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1999, ISBN 3-201-01716-7 , p. 38

Investigations

- Richard Bohn : The sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros ( Antiquities of Pergamon , Volume II). 2 volumes, Speman, Berlin 1885 Digitization of the text volume , digitization of the table volume .

- Wolfram Hoepfner : Eumenes' II library in Pergamon. In: Wolfram Hoepfner (Hrsg.): Ancient libraries. Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2846-X , pp. 41-52.

- Wolfram Hoepfner: To Greek libraries and bookcases. In: Archäologischer Anzeiger . 1996, ISSN 0003-8105 , pp. 25-36.

- Harald Mielsch : The library and the art collections of the kings of Pergamon. In: Archäologischer Anzeiger. 1995, pp. 765-779.

- Volker M. Strocka : Once more about the Pergamon library. In: Archäologischer Anzeiger. 2000, pp. 155-165.

- Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck : On the equipment and function of the main hall of the Pergamon library. In: Boreas. Münster contributions to archeology. Volume 18, 1995, ISSN 0344-810X , pp. 45-56.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Jenö Platthy: Sources on the Earliest Greek Libraries with the Testimonia , Amsterdam 1968, pp. 159-165.

- ^ Wolfram Hoepfner: Pergamon. Rhodes. Nysa. Athens . In: Wolfram Hoepfner (Ed.): Antike Bibliotheken , Mainz 2002, pp. 67–80, here: p. 68.

- ↑ E.g. Wolfram Hoepfner: The Library of Eumenes II. In Pergamon , Mainz 2002, p. 42.

- ^ A b c Richard Bohn: The Sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros , Volume 1, Berlin 1885, pp. 56-67.

- ↑ Wolfram Hoepfner: The Library of Eumenes II. In Pergamon , Mainz 2002, p. 42.

- ^ Plutarch , Marcus Antonius 58.

- ^ Galenus, Commentarius in Hippocratis de officina medici 1,18,2.

- ↑ Strabo , Geographica 13,1,54.

- ↑ Galen, Peri ton idion biblion 6th

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus , De Dinarcho 1,11.

- ↑ Rudolf Blum: Callimachos. The Alexandrian Library and the Origins of Bibliography. Madison 1991, p. 156.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Ad Ammaeum 1,4.

- ↑ Athenaios, Deipnosophistai 8,336e.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios , On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 7:34.

- ↑ a b Johannes Lydos , De mensibus 1,28.

- ↑ a b Otto Mazal: Greco-Roman Antike , Graz 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Vitruvius, De architectura 7, foreword, 4.

- ↑ Wolfram Hoepfner: The Library of Eumenes II. In Pergamon , Mainz 2002, p. 41.

- ↑ Strabon, Geographica 13,624.

- ^ Karl Dziatzko: Pergamenische Bibliothek , Stuttgart 1897, Col. 414.

- ↑ Galen, Commentarius in librum Hippocratis de natura hominis 1.127 and 2.128.

- ↑ Pliny , Naturalis historia 13.70.

- ↑ Wolfram Hoepfner: The Library of Eumenes II. In Pergamon , Mainz 2002, p. 52.

- ^ Richard Bohn: The Sanctuary of Athena Polias Nikephoros , Volume 1, Berlin 1885, pp. 67-69.

- ^ Karl Dziatzko: Libraries . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science , Stuttgart 1897, Sp. 414 f.

- ^ Bernt Götze: Ancient libraries . In: Yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute 52, 1937, pp. 223–247, here: pp. 225 f.

- ^ Christian Callmer: Antique Libraries. In: Opuscula Archaeologica 3, 1944, pp. 145-193.

- ↑ Carl Wendel: The structural development of the ancient library . In: Central Journal for Libraries . Volume 63, 1949, pp. 407-428 = Carl Wendel: Small writings on ancient books and libraries. Cologne 1974, pp. 144-164.

- ^ Doris Pinkwart: Library. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 2, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1976, ISBN 3-11-006740-4 , p. 502 ff.

- ^ Elzbieta Makowiecka: The origin and evolution of architectural form of Roman library. Warsaw 1978, p. 15 ff.

- ↑ Volker M. Strocka: Roman Libraries. In: Gymnasium 88, 1981, pp. 298-329.

- ^ Lora Lee Johnson: The Hellenistic and Roman library. Studies pertaining to their architectural form. Providence 1984 (dissertation).

- ↑ Harald Mielsch: The library and the art collections of the kings of Pergamon , 1995, pp. 765–779, here especially pp. 770–772.

- ↑ Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: On the equipment and function of the main hall of the library of Pergamon. In: Boreas. Münster's contributions to archeology 18, 1995, pp. 45–56.

- ↑ Volker M. Strocka: Once again on the Pergamon library , 2000, pp. 155–165.

- ↑ Wolfram Hoepfner: To Greek libraries and bookcases , 1996, pp. 25–36; Wolfram Hoepfner: The Library of Eumenes' II. In Pergamon , Mainz 2002, pp. 41–52.

- ↑ Wolfram Hoepfner: Eumenes' II library in Pergamon , Mainz 2002, pp. 41–52, here: pp. 44–48.

Coordinates: 39 ° 7 ′ 55.8 ″ N , 27 ° 11 ′ 2.9 ″ E