Lorch fort

| Lorch fort | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 63 ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Route 12 |

| Dating (occupancy) | around 150/160 AD to around 260 AD |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | Cohors equitata |

| size | 153.5 (154) m × 158.4 (162.8) m = 2.47 ha |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | The foundations of the north gate tower of the west gate are visible |

| place | Lorch |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 47 '53.9 " N , 9 ° 41' 15.1" E |

| height | 285 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Fortress of Welzheim (north) |

| Subsequently | Kleindeinbach small fort (east) |

The fort Lorch was a Roman frontier fort near the Rhaetian Limes , the status since 2005 UNESCO world cultural heritage has. The garrison, presumably built around 150/160 AD, is now in the middle of Lorch , a town in the Ostalbkreis , Baden-Württemberg , and is almost completely built over.

location

The fort was built on the north side of the Remstal valley, which is oriented from west to east in this area, at the exit of a smaller but deep depression running from north to south. In ancient times, an important long-distance connection from Cannstatt ran along the Rems . The Roman border palisade ran on the northern parts of the terrain high above the Remstal, which , coming from the north, made a sharp bend to the east near Lorch. In addition to securing the Limes, Lorch was also the last major military site in the Roman province of Germania superior in this section . The province of Raetia began only a few kilometers to the east . The next cohort fort was there on the southern slope of the valley at the Schirenhof .

Research history

First assumptions for a Roman camp site were made in the middle of the 19th century. The first soundings were carried out in 1893 by the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) under Major Heinrich Steimle , a route commissioner . Due to the difficult local situation, further possibilities did not become available until 1895/96, when a sewerage system was built in the fort area. Overall, the RLK mainly recorded sections of the surrounding wall.

During construction work in the past, remnants of the ancient camp village were repeatedly found to the west and east of the military area. In 1954 the burial ground was cut. However , the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office did not carry out the first area excavation in the fort itself until 1986/87 when an underground car park was being built between Kirchstrasse and the town hall. The cut part of the camp belonged to the southeast quarter of the facility. Despite the partial disturbance of the Roman building remains by medieval and modern interventions, this excavation was able to provide the first important results on the structure of the garrison.

Fort Lorch is now an archaeological monument.

Building history

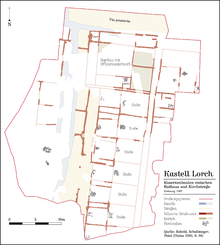

Research assumes that the 2.47 hectare fort was occupied by a previously unknown partially mounted unit after its construction, which had previously been stationed in the Köngen fort on the Neckar . The east and west sides of the facility were 153.5 and 154 meters long. The north side measured 158.4 meters, the south side 162.8 meters. The defensive walls were rounded at the four corners (playing card shape).

Experts attribute the fact that the surveyors at that time shifted the floor plan somewhat to possible device errors at the time. Overall, however, as research suggests, the stone lining followed a set standard plan. Nothing is known of an older wooden fort, even if there were coin finds early on, some of which date back to the time when Fort Lorch was built. However, this is not unusual. For example, lost coins from pre-Augustan times were found in the baths of the Schirenhof fort. Dendrochronological investigations on the wooden palisade of the nearby Upper German-Rhaetian border fence at the Kleindeinbach small fort have shown that it was most likely built in AD 164. Similar findings were made on the palisade from Schwabsberg . A simple fence uncovered at Limestor Dalkingen , which, according to the local excavator Dieter Planck, was erected in front of the palisade around 130/135 AD, confirms the information from Lorch that this fort was built in around 159 AD after the kings were cleared bed the time "by 150". Really clear information could only be given by a wood finding from the fort itself.

The up to 1.3 meters wide defensive walls, which were covered with carefully worked, up to 0.3 meters wide wall shells made of the local parlor sandstone, encompass an almost square garrison site. This location was aligned with its length and width almost exactly in west-east and north-south direction. The position of the Praetorial Front is, however, not yet known. The principia , the staff building, could only be uncovered in small remnants. Today there is a cemetery above them. It was assumed, however, that the Porta praetoria , the main exit gate, pointed to the west, to Bad Cannstatt. At the same time, this western gate with its double passage flanked by two towers is also the only known entrance to the inside of the camp. During the 1986/87 excavation, at least two wooden crew barracks (centuriae) were uncovered in the south-east of the fort district , with their long sides pointing almost exactly in a north-south direction. The head building of these barracks, in which the centurion and possibly other officers, NCOs and staff once lived, was to the north. It was followed by one of the main camp roads. In the corresponding excavation drawing, the name Via Praetoria was entered for this street , since in a second theory of the fort's orientation, it was also thought on its east side, in the direction of Raetia. The hearths of the individual contubernia, made of brick slabs and exposed in the barracks, were partially well preserved.

Vicus, fort bath and cremation cemetery

The fort village, the vicus , has only been known in isolated traces east and west of the fortification. Its full dimensions cannot therefore be grasped. The buildings of the vicus residents erected on narrow parcels were erected at the gable facing the arterial roads. The numerous ceramics recovered from the residential area, despite the limited evidence, originated in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The image of the originally Celtic goddess Epona , the protector of horses and the local hearth, on a small sandstone relief became famous. In addition, the inscription of a pottery dealer has come down to us from the Lorcher vicus .

The fort bath was probably in front of the Porta decumana , the eastern back gate.

The remains of one of the two burial grounds have been identified around 500 meters southwest of the garrison. The archaeologists came across urns and gift vessels, among other things.

Troop

The discovery in Lorch of a bronze pendant with a punched inscription in the form of a Roman votive sheet clearly confirmed the assumption that a Cohors equitata , a partially mounted unit, was stationed there. Unfortunately, the inscription does not reveal which cohort it was specifically. The partially mounted units, which were part of the regular auxiliaries ( Auxilia ), had an actual total strength of around 480 men, one third of which was cavalry.

Since a large number of forts had become very remote and militarily useless when the Limes was moved forward, they were abandoned and the crews moved forward to the new border. The Köngen fort , which was also occupied by a previously unknown Cohors equitata , was evacuated probably in AD 159 . In the course of researching individual units of the Roman military, the assumptions have condensed to the point that a change of the partially mounted Köngener unit via the connecting Roman road to Lorch is considered very likely.

Militaria

High quality militaria was recovered in Lorch. These include a 16.5 centimeter high bronze model of a sign of victory (tropaeum) from the 2nd century, discovered near the fort , which is now in the Limes Museum in Aalen . Originally, the larger- than -man-size Tropaea were placed as victory memorials at the point where an enemy had been defeated and decorated with weapons and military equipment. During the excavation in 1986 a bronze mount with a gorgon head was found. In addition, a large number of small finds such as sword sling holders made of iron and bronze came to light.

Post-Roman development

The archaeological in 9./10. Holy Cross Church, which was first recorded in the 18th century, was first mentioned in 1140. It was built within the fort walls, roughly in the middle of the north gate. The emergence of Christian sites above Roman forts, especially in the area around the former staff building, is not so unusual. A similar constellation could also be observed at the Raetian Limes forts in Gunzenhausen , Böhming and Kösching . Inside the Lorcher church, a Roman wall was recorded, the rising masonry of which was still partially preserved. It was suspected that this remains of the building may have belonged to the former Principia .

Monument protection

The Lorch fort and the aforementioned ground monuments have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage as a section of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, the facilities are cultural monuments according to the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg (DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . Mann, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3786117012 , p. 250.

- Dieter Planck , Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 101.

- Stefan Pfahl: The Roman bronze trophy by Lorch and related pieces . In Find reports from Baden-Württemberg 18 (1993), pp. 117–135.

- Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer , Andreas Thiel : The Limes. The German Limes Road from the Rhine to the Danube . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3806214611 , p. 98.

Web links

- Fort Lorch on the side of the German Limes Commission; Retrieved July 29, 2014.

Remarks

- ^ Bernhard Albert Greiner: The contribution of the dendrodata from Rainau book to the Limesdatierung. In: Limes XX. Estudios sobre la fontera Romana. Ediciones Polifemo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 978-84-96813-25-0 , p. 1289.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 54.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 58.

- ↑ fort Schirenhof at 48 ° 47 '8.79 " N , 9 ° 46' 31.15" O .

- ↑ Dieter Planck: New excavations on the Limes (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany [= Writings of the Limes Museum Aalen ]. 12). Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, p. 23.

- ↑ fortlet small Your stream at 48 ° 47 '51.11 " N , 9 ° 45' 15.53" O .

- ↑ Bernd Becker: Felling dates for Roman construction timbers based on a 2350 year old South German oak tree ring chronology . In: Find reports from Baden-Württemberg , Volume 6, Theiss, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 380621252X , pp. 369–386.

- ^ Wolfgang Czysz , Lothar Bakker: The Romans in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3806210586 , p. 123.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 188 ff.

- ↑ CIL 13, 06524

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 36.

- ^ Philipp Filtzinger : Limes Museum Aalen . 2nd edition, Gentner, Stuttgart 1975, p. 46.

- ↑ a b Stefan Eismann: Early churches over Roman foundations. Investigations into their manifestations in southwest Germany, southern Bavaria and Switzerland . Leidorf, Rahden 2004, ISBN 3896467689 , p. 238.