Welzheim castles

The forts of Welzheim were two Roman military camps on the Front Limes , a section of the UNESCO World Heritage Site " Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes " in the area of today's city of Welzheim in the Rems-Murr district in Baden-Württemberg . The well finds from the east fort contributed to the most important findings that were gained at this excavation site. They gave a comprehensive insight into the vegetation and the living conditions of the inhabitants in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

West Fort (Alenkastell)

| West Fort Welzheim | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 45 ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) |

Upper German Limes Vorderer Limes, route 9 |

| Dating (occupancy) | around AD 159/160 to around AD 259/260 |

| Type | Alenkastell |

| unit | "Ala I ..." (?) |

| size | 236 m × 181 m (= approx. 4.3 ha) |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | almost completely built over; not visible |

| place | Welzheim |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 52 '20.2 " N , 9 ° 37' 56.8" E |

| height | 500 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Small fort Rötelsee (north) |

| Subsequently | Lorch Fort (south) |

The west fort Welzheim is almost completely built over today. It was connected by a road to the smaller and much better explored eastern fort, 530 m to the east. The west fort was the garrison site of a cavalry unit that served the border guard.

location

A straight section of the Limes, around 80 kilometers long and running from north to south, ends at Welzheim. The city is one of the few places on the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes that had two forts. The garrison, located almost exactly on an exact west-east axis, was located on an eastward sloping slope in the south of today's city of Welzheim and was almost completely overbuilt after the Second World War. Slightly to the west of today's Schloßgartenstrasse – Christian-Bauer-Strasse intersection was the Porta praetoria , the main gate of the camp, the location of which was the focus of the entire development. In an easterly direction, Christian-Bauer-Straße takes up the alignment of the ancient camp street with the Principia , the staff building. The entrance to the staff building was roughly where Christian-Bauer-Strasse meets Schorndorfer Strasse. Schorndorfer Straße runs in a north-south direction almost exactly above the former large vestibule , a multi-purpose building that lay like a bolt across the staff building. A path runs parallel to the Westwall, the former fortification wall, and behind it, also following the direction of the fort, the railway embankment. Welzheim train station is just in front of the former north-west tower of the fortification. The short street going east from the station square follows the north wall of the fort for a while.

Research history

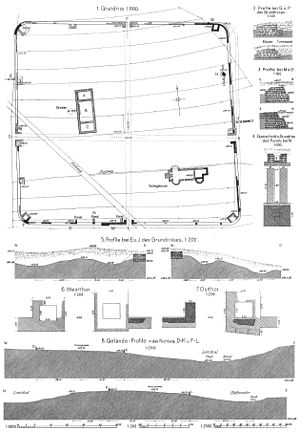

After its discovery in 1895 by a chief forester, the system was partially excavated by the Reich Limes Commission (RLK). It was found that the 236 × 181 meters (= 4.3 hectares) large western fort, which at that time was still almost unbuilt on the outskirts, is one of the largest facilities on the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. As early as the end of the 19th century, but especially after the Second World War, the ancient area was released for permanent overbuilding and thus for almost complete destruction. Even today, new industrial building measures are being carried out on the site. Only a few ancient structures are still protected under meadows. It wasn't until 1980 that an emergency excavation took place for the first time since the days of the RLK. A part of the courtyard of the Principia , the staff building, was cut. In 1983 a rescue excavation followed on the south-southeast corner of the fort. This is due to the building of a factory. In 1989 research was carried out on the south wall and in 1990 to the east and near the Porta principalis sinistra , the north gate. In 1997, two areas on Via praetoria , the main warehouse road leading to the east gate, were uncovered, and in 1999 a section of the wall with the first intermediate tower west of the Porta principalis dextra , the south gate. The largest modern rescue excavation to date was triggered from June 2005 to October 2006 by the expansion of a production hall. The damage caused by those responsible led to the loss and final destruction of the largest still connected open area of the fort, which included the eastern part of the staff building and a strip of the Retentura , the rear camp, up to the Porta decumana , the western gate. The excavations were initially led by Rüdiger Krause and from the beginning of 2006 by Klaus Kortüm .

Building history

The dimensions of the Welzheimer West Fort, planned exactly according to the cardinal points, can be compared in Upper Germany with the stone fort Niederbieber (5.25 hectares; built shortly after 185/190) or with Echzell (5.2 hectares), which in each case suggests large occupations. The research also found that forts in their complete system on the Germanic Limes were usually larger and more generously dimensioned than the British fortifications occupied by a comparable force. Welzheim West was twice the size of comparable facilities there. In addition to regional differences, it was assumed that only parts of units were stationed in these respective camps in Britain, which not only raises questions about a possibly different organization of the Roman army there, but also remains unsatisfactory, since this thesis cannot be verified. Solid evidence of an older wood and earth fort was not discovered during the 2005/2006 excavation campaign either. As a final coin from the fort since its discovery in 2006 a penny from the reign of Emperor applies Alexander Severus (222-235). More recent coin finds in Welzheim only come from the area of the camp village.

Enclosure

In the course of the excavations at the end of the 19th century, the area of the rectangular complex was determined to be 236 × 181 meters (= around 4.3 hectares) and three of the four gates were at least partially exposed, whereby it was finally possible to determine that all four inlets were probably had a two-lane driveway and two towers flanking these driveways. The Porta praetoria , the main and east gate in Welzheim, has already been exposed by the RLK. It is the only completely excavated gate to this day. The northern gate tower of the Porta decumana was 4 × 4.5 meters in size and had a foundation around 1 meter wide. Only on its outside was it made much more massive at 1.5 meters. Since the second gate tower has not yet been excavated, the exact width of the Porta decumana could not be determined even after the 2005/2006 excavations. A reflection of the gate tower on the known central axis of the camp would result in a width of around 13 meters. A double-gate access would also be expected here. The finding of the four rounded corners (playing card shape) also fits into the typical appearance of the forts of this time. Watchtowers built against the wall had been erected in these corners. During the excavation in 1983, another 20-meter-long section of the defensive wall was uncovered. An inner wall shell between 0.5 and 0.6 meters high in this area came out of the ground. Its external counterpart, however, only had three to four stone layers. On the south-eastern corner of the fort, which made a large arch there, the researchers uncovered a slightly trapezoidal tower, which is relatively small in relation to the size of the camp and which, with its masonry preserved up to one meter high, was surprisingly well preserved. The side of the tower facing into the fort had a 1.2 meter wide entrance. Closer investigations showed that the tower was raised in one piece with the camp wall. It could be proven that on the excavated south and east sides of the wall an earth ramp had been built up inside. Due to the favorable soil conditions, wood inlays within a ramp were detected for the first time at that time, which were supposed to ensure the stability of the embankment. The completely and primarily charred wooden construction consisted of planks partly parallel to one another and partly in a grid-like manner. Charring is an ancient conservation method used to make wood more durable. During the excavations in 2005/2006, the defensive wall was cut again. This time on the west side. The north tower of the Porta decumana came to light, as did a 30-meter-long section of the western, 1.6-meter-wide fort wall. As the archaeologists found, this wall rested on a foundation around 2 meters wide and 0.7 meters deep. The earth ramp adjoining the interior of the camp was measured with a width of around five meters. It was still recognizable as a clay compression almost 0.2 meters thick. The findings of charcoal strips made in it coincided with the discovery of a wooden insert in the embankment, which was found in 1983 in the area of the southeast corner in a significantly better condition at that time. The camp had a total of ten intermediate towers. On the west and east side one each between the gates and the corner towers, on the north and south side one each in the praetentura , the front bearing, one each in the latera praetorii , the central bearing, and one each in the retentura .

In front of the defensive wall, a ditch could be recognized on the western flank and the southern wall until 1983. During three excavations between 1989 and 1999, further trench cuts were carried out, which ultimately resulted in the certainty that the west fort was surrounded by three pointed trenches, the outermost of which were up to thirty meters away from the defensive wall. At the Porta decumana it was proven that at least the innermost trench in front of the gate did not fail.

Interior development

Via sagularis

During their excavation in the southeast corner area in 1983, the archaeologists found two cisterns, which were about 0.8 meters deep into the historical ground level, along the section of the Via sagularis they uncovered , the Lagerringstrasse. In 2005/2006 the Via sagularis was cut again in the western excavation area north of the Porta decumana , although the route itself could not be explicitly recognized. So it could only be determined in this area by the dimensioning of the zone between the foot of the earth wall and the beginning of the wooden structures encountered. This resulted in a width of around five to six meters. The formerly covered drainage ditch , which stretched along the Via sagularis and kept a distance of three to four meters from the earth ramp, gave a clear indication of the former road . The Ringstrasse was narrowed by two wooden-paneled box pits, possibly cisterns. Some of these intervened in the base of the wall and reached around one meter below the Roman horizon . Some other hollows in the area of the via sagularis , some of which reached under the sewer ditch, could stem from early efforts to keep the path area dry.

Via decumana

During the 2005/2006 excavations, the excavators found that the Via decumana , which was cut on its north side and the rear main road leading to the west gate, no longer offered any tangible archaeological findings.

Via praetoria

In 1997, the Via praetoria was cut in two excavation areas. It was observed that this main camp road was accompanied on its north side by a once well-covered drainage ditch, which apparently led the sewage out to the Porta praetoria , the east gate of the fort.

Crew barracks and cellars

For the first time in 1983, traces of wooden interior structures were found in the south-eastern corner of the fort. It became clear that the team barracks and other buildings were made of half-timbered construction. In 2005/2006 the Retentura was cut. The wooden barracks uncovered here could be clearly assigned in terms of their function. The archaeologists found 200 pit-like depressions in the strip north of Via Decumana , eleven of which could be defined as cellars. Six of these cellars were four to six square meters in size (K2, K5, K8–11), all other 10 to 15 square meters (K2, K3, K4, K6, K7). The latter were exclusively closer to the Via decumana, which ran exactly in a west-east direction . All cellars had approximate standing height. The excavator Klaus Kortüm assumes that some of the box pits that were found, which had sides between 1 and 1.8 meters in length and were around 1.2 and 2 meters deep, can be referred to as cisterns. Evidence of a latrine could not be provided, but remained under discussion. None of these pits had any contact with water. Most of the depressions in the western excavation area, about 0.8 meters below the ancient running horizon, are to be regarded as storage pits, while others were once used as drainage and waste pits. The latter two depressions were mainly found in the vicinity of the Via decumana and the staff building. In most cases, a clear separation of the pits was no longer possible. The half-timbered buildings by barracks over the storage pits and cellars were founded on swelling beams. Evidence of these buildings was often difficult to provide. One exception was the area of an ancient fire rubble plan. Nevertheless, the archaeologists were no longer able to capture the details of the floor plans. After comparing the findings with the interior development in the rear camps of the Reiterkastelle Heidenheim , Ruffenhofen , Weißenburg , Aalen and Pförring , the architecture should be based on the Pförring measurements, as the similarity of the overall constellations in this part of the two camps is convincing .

Principia

Of the interior development, only parts of the stone-built Principia were examined by the RLK . A largely standardized building typical of the Middle Imperial Era was identified, in which the administration tracts were grouped around an inner courtyard and in front of which was a 16 × 69 meter multi-purpose hall above the Via principalis . In the rear, western part of the building, a flag shrine with an apse was proven. The design of these sanctuaries with apses had become common in the forts of the Germanic provinces since the middle of the 2nd century, which among other findings gives an indication of the time of origin. The main axis of the staff building was oriented towards the east, towards the Praetorial Front , on its north and south side, according to the RLK, only one elongated brick room line could be determined, which stretched over the entire width of the inner courtyard. As with other fort sites, it can be assumed that there were wooden partition walls in both rooms, which were used to divide individual rooms. To the east of the two rooms and the inner courtyard, a 14-meter-wide transverse hall with a cantilevered roof was found. As the reinforcing pillars show, this basilica, together with the multi-purpose hall, was architecturally elevated. A wide main entrance was in the middle of the courtyard. On the northern front side there was also a smaller entrance near the northwest corner. Whether there was such a thing in the south is unknown due to the lack of excavation results. A small rectangular apse built in the middle on the north side of the basilica may have been later converted into a nymphaeum, according to Kortüms. An internal finding discovered during the 2005/2006 excavation in the north-eastern area of the hall consisted of poorly preserved foundations and stone structures, the meaning and purpose of which have so far remained unknown. It was in this area that the most recent archaeological findings from ancient times came out of the ground. Stones with traces of fire were discovered in one area, and a small metal hoard was found nearby, which had subsequently been deposited between the bricks of the hall that had perhaps already collapsed. The hoard consisted of a rectangular grid, a stove shovel, a wooden spade fitting and a small Gallo-Germanic bronze bucket from the 3rd century. All objects that could have come from the room of a contubernium in the fort.

Finds from the fort area

In 1897, the fragment of a round table top made of parlor sandstone with an inscription was uncovered in the Principia . On the top of the table a two-line inscription ran along the edge and words were also carved on the edge of the table. Only fragments of these texts have survived:

- --– sub] cura M [---]

- [---] sesq (uiplicarius) al [ae // ---] OS IM [---

The stone is now in the Württemberg State Museum .

During the rescue campaign from 2005 to 2006, the archaeologists discovered in a pit behind the Principia a precious hexagonal bronze bottle from the 2nd or 3rd century, elaborately decorated with enamel , in which valuable oils or ointments may have been filled. In addition, various forms of fibula, often in the shape of a swastika, and small military parts came to light during this excavation.

Fort bath

About 100 meters down the slope and southeast of the Porta praetoria , in the “Brühl” corridor, was the well-preserved 16 × 44 meter row bathroom of the west fort when it was discovered in 1896. With apodyterium (changing room), frigidarium (cold water bath) with bathing pool, tepidarium (warm air room) , caldarium (warm water pool) and a large praefurnium (boiler room). There the air for the hypocaust heating was heated.

Troops and military personnel

A sesquiplicarius alae of unknown name is mentioned on the inscription found in the Principia . The sesquiplicarius alae belonged to the rank of non-commissioned officer within a cavalry unit. He received one and a half times the pay. A Sesquiplicarius was usually the third deputy of the Decurios (Rittmeister).

According to an inscription that has only been partially preserved, the West Fort Welzheim was the location of an "Ala I ...". As far as could be determined, only three possible ales come into consideration: the Ala I Scubulorum , the Ala Indiana Gallorum or the Ala I Flavia Gemina .

Ostkastell (numerus fort)

| Ostkastell Welzheim | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 45a ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) |

Upper German Limes Vorderer Limes, route 9 |

| Dating (occupancy) | around AD 159/160 to around AD 259/260 |

| Type | Numerus fort |

| unit | "Numerus Brittonum ..." (?) / Exploratores |

| size | 123 m × 126 m (= 1.6 ha) |

| Construction | stone |

| State of preservation | West gate with part of the wall reconstructed, the walls restored and the stone building on the ground indicated |

| place | Welzheim |

| Geographical location | 48 ° 52 ′ 17 " N , 9 ° 38 ′ 32" E |

| height | 490 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Small fort Rötelsee (north) |

| Subsequently | Lorch Fort (south) |

The Ostkastell Welzheim is largely preserved in the ground in the form of an archaeological reserve and open-air museum. The fortification built for a crew of 150 to 200 men ( numerus ) was connected to the much larger cavalry fort 530 meters to the west by a road and a camp village. When the Limes fell around AD 260, the facility sank. The west gate was scientifically reconstructed with a section of the defensive wall.

location

The east fort Welzheim, located on the “Bürg” corridor, is located on a plateau above the Lein . The Roman surveyors used a spur of the plateau sloping to the south, east and north for the construction site, which gave the camp crew a good overview, whereby the site on which the fort was built sinks by around ten meters from northwest to southeast. What is unusual about the Ostkastell is its obvious location just before the Limes, already outside the actual Roman Empire.

Research history

As the field name shows, the knowledge of an old fortified site has never been completely lost. The garrison, known as a Roman base since the 18th century and examined by Konrad Miller for the first time in 1886 , was researched by the route commissioner Adolf Mettler in autumn 1894, at that time still in the open , with special attention also being paid to the fence has been laid. As is the case with the western fort, step by step, the eastern fort was to be completely built over from 1960 onwards. This prompted Hartwig Zürn , then head of the soil monument preservation department at the Baden-Württemberg State Monuments Office , to undertake a major rescue operation with the help of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the Roman-Germanic Commission (RGK) and the Saalburg Museum to ensure that the state was preserved acquired the historically valuable fort area. The original plan was to completely excavate the fortification, restore the foundations of the stone fort and make it accessible to the public. But in 1976, when Zürn's successor Dieter Planck was supposed to start the excavations, the opinion about the previous excavation concept changed:

- “When I received the order in 1976 to start the excavation work, it was clear that the solution envisaged at the time would have also meant the final destruction of this facility. For this reason I have tried to develop a different concept, on the one hand to meet the justified desire of the public to be able to see something and on the other hand to preserve this fort as an archaeological reserve for future scientific excavations. "

The new concept envisaged exposing and preparing the fence so that visitors could understand the size of the camp. It was also decided to rebuild the west gate. For the first time since the imperial era in Germany, an attempt was made to carry out a major reconstruction attempt on a fort from a purely scientific point of view, which reflected the latest state of research. Dietwulf Baatz from the Saalburg Museum and the State Monuments Office played a major role in the groundbreaking reconstruction . In 1983 the first stage of the fort presentation was presented to the public after the excavations and reconstruction had been completed.

- “We dared to take the step from conservation to reconstruction, and I believe that in individual cases we should continue to do so in the future, whereby the visitor must receive clear information about what is secured and what has been supplemented according to the most modern scientific findings. ... However, we are of the opinion that reconstructions should only be made in individual cases. The example of Welzheim can be seen here as particularly fortunate for the future work of archaeological monument preservation. "

Because the east fort as an archaeological reserve is to be preserved for future research, the excavations, which were completed in 1981, mainly explored the defensive wall, gates and towers. In the case of the interior constructions, one counts mainly with wooden houses, which could provide important information about the fort and Limes. At the beginning of the 1990s, an electromagnetic and geomagnetic investigation of the storage area took place. With a redesign of the fort area in 1993, due to which, in addition to the previously installed casts of inscriptions from Welzheim, stones from the entire Upper Germanic area are now shown, the open space was given the name Archaeological Park Ostkastell .

Building history

Despite the militarily successful choice of location for the approximately 123 × 126 meter (= 1.6 hectare) east fort, the subsoil was less suitable and led to several collapses of the 1.1 to 1.4 meter wide fort wall, which were removed during the excavations In 1976 in the area of the west and south gates, as well as the south-west corner tower, it was partially still over 1.2 meters high. The mortar securing the stone structure, however, had completely dissolved due to the lime-poor soil. The main reason for the destruction of the masonry could be the almost non-seeping rainwater on the sloping hillside of the fort, which the Romans opposed with six small masonry drainage channels in the southwestern wall foundation. Large post pits on the outside of the fort, in which wooden scaffolding were once founded, tell of the repair work on the defensive wall . In Fort Murrhardt 1979 similar findings were found. In the southern part of the eastern fort, the wall also served as a terrace wall, as it had to support the approximately 0.5 meter higher level inside the fort.

The extent to which the geometers and experts were already aware of the disadvantages during the construction of the stone fort is beyond our knowledge, however, not only were the multiple renovations mentioned, but it was also established that the reinforcement of the fortifications only happened gradually and over a longer period of time . It could also be proven that this expansion did not correspond to the typical Roman norms of the time of construction on the Germanic Limes. For Planck and Hans Schönberger, the previous finds, especially the rich inventory of terra sigillata , allowed the possible conclusion that the east fort was built around a generation before the west fort in the late Hadrian or early Cantonese times.

On the inside of the wall, parallel post holes were discovered that once supported a wooden battlement. In front of the wall was a double-pointed trench that exposed at the four inlets of the camp. The single-lane south gate and the similarly designed north gate each had only one tongue wall, no towers, in the width of the battlements. Such gate cheeks are usually only detectable in small forts such as Rötelsee . Archaeologists discovered the old paving in the 1976 passage. The later reconstructed two-tower west gate with its 3.6 meter wide passage, however, follows the usual construction scheme and was examined in 1977. As in the southern part of the fort, the excavators were able to discover various repairs and determine the dimensions of the two gate towers at 3.8 × 4 meters.

The excavations of the RLK in 1894 on the north-east tower and the east gate had already suggested several profound renovation phases connected with the difficult subsoil. The single-lane east gate had only one tower in the north, while a tongue wall stood on the south side. Another special feature was that there were intermediate towers only on the west side and on the west part of the north side.

As could be seen, the fence was built in two different construction phases. First of all, trenches, walls and gates as well as the interior buildings were built. The tongue walls of the gates in the south, north and east, which were still visible up to the end of the fort, probably belong to this period. A fire horizon, which can be dated to the time around 170/175 through finds, can probably be associated with the Marcomann Wars (166–180) and shows a similar time period as a layer of fire from the Murrhardt castle. Only after this destruction did the fort receive its four corner, intermediate and perhaps also gate towers, which can also be seen through construction joints.

The Principia could not yet be proven, which is why the Praetorial Front is unknown. After evaluating geophysical measurements, however, there was most likely a staff building.

In 1977, when exploring the west gate, two wooden buildings were cut from the interior. In addition, the Via sagularis , the Lagerringstrasse, was measured with a width of 3.3 meters.

Well finds

When the area of the camp road was cut, the archaeologists were able to uncover four wood-paneled wells with some spectacular finds. In addition, the research gained a large amount of data on the living conditions in a small Roman border fort almost 2000 years ago. As was common in earlier times, abandoned wells were often reused as waste pits. These pits are often important time windows into the past for excavators, as the finds recovered here have often only rarely been preserved elsewhere.

For the two most interesting water points, wells 1 and 2, the dendrochronological investigation showed that well 2, which was completed around 165 AD, was the first to be abandoned. As a replacement, the fort crew set up well 1 in 190 (± 10) AD, which stood directly next to the south-west corner tower of the fort. Its abandonment and backfilling is dated between 230 and 250.

When excavating the older well 2, the archaeologists found a very well-preserved wooden, toothed cladding measuring 1.5 × 1.5 meters. This cladding could be observed right down to the small, also preserved well room. With its light brown, clayey backfill, Brunnen 2 stood out clearly from its younger successor, in which the excavators came across black-brown, soapy filling material. Well 1, whose formwork was mortised, was also in excellent condition from a depth of almost two meters due to the soil conditions.

Craft items

Well 2 contained a wooden shovel, a broken yoke, a copper bucket and large remains of a masked helmet made of sheet iron with oriental features and strongly curled hair, along with a number of other wooden objects.

The finds recovered from the younger well 1 testify to a homogeneous filling, mainly with the material of a cobbler's shop. Their spectacular legacies consisted of around 100 leather shoes, which offered a cross-section of all footwear in use at the time, from toddler shoes to boots, with most shoes already expired. A similar finding, albeit from different wells, comes from the vicus of Kastell Buch . In addition to these finds, a large number of everyday utensils such as a writing board or ceramics were recovered. In addition, wood residues could be secured in large quantities; seeds and fruits were also found. The prehistoric botanical investigations carried out under the direction of Udelgard Körber-Grohne at the University of Hohenheim identified imported objects made of cedar and cypress wood.

Militaria

Around 190 AD the soldiers began to use well 2 as a waste pit. Interesting military equipment also got into the ground. In well 2, three pila muralia (“wall spears”) up to 1.84 m long in excellent condition were found. The pila muralia , actually valli ("entrenchment posts"), are entrenchment posts for short-term overnight camps in external operating areas. The stakes could also be used as an approach obstacle in the manner of Spanish horsemen against enemy infantry and cavalry. How u. a. Caesar reports that the stakes, now as massive projectiles, were thrown from the walls at attackers.

As already mentioned, larger remains of a helmet mask, which was missing the occiput, came to light at the bottom of well 2. The 25 centimeter high mask, restored in the Roman-Germanic Central Museum, belongs to the Alexander type and can be seen in the 2nd / 3rd Date to the 17th century AD. (Junkelmann 1996, Catalog No. O 99)

Research assumes that the face helmets of the Alexander type used by the Roman cavalry received their final shape in Hadrianic times. The earliest piece to date is said to have been found together with Roman infantry clothing in a cave on Mount Hebron and can be dated to the time of the Bar Kochba uprising (132 to 135 AD). Typical of this Hellenistic helmet mask , which has developed from a masculine-feminine mixed type, are among other things a small mouth, a straight nose, long sideburns and an almost baroque hairstyle with "Alexander curls". Masked helmets of this time were mainly not worn in combat, but only for parades and exhibition fights, in which the Roman cavalry showed their skills. The course of such an exhibition match is reported by Flavius Arrianus in his equestrian tract published in AD 136.

Fruits, vegetables, salads and herbs

In fountain 1, there was a large stock of items that were used in Roman cuisine and items of field crops that were imported or grown or collected on site. So it was possible to detect imported figs , but also grapes , plums , wild strawberries, raspberries , blackberries , rose hips , blueberries , apples, hazelnuts and walnuts and the like. v. a. It became clear that the locally collected forest berries dominated the fruit in Welzheim. Lamb's lettuce , carrots , parsnip, green foxtail, Roman sorrel and garden algae could be recognized on leafy vegetables and salads . Field beans, lentils and peas represented the legumes . Of the eight vegetable and aromatic plants that were found, the researchers identified coriander as the first one . In addition, dill , thyme , celery as well as some medicinal plants and different types of grain were found. In addition, evidence was provided for flax and poppy seeds, although the poppy seeds were still at a very early stage of domestication.

Grasses and fields

Well 1 also contained the plant remains of over 60 grassland species. It was found that the mowing came from good meadows with fresh to dry locations as well as from stream meadows. It is assumed that the clippings from the meadows were intended as fodder and the fat alluvial grass for bedding. The statement that the Roman meadows of that time must have been in excellent condition is given by plant species such as bluegrass (Poa) , ball grass (Dactylis) and comb grass ( Cynosurus cristatus ). The swamp bluegrass (Poa palustris) could be identified as the most common occurrence . In addition, many ostrich grasses (Agrostis) , common plantain (Plantago media) and common buttercups (Ranunculus acris) were discovered. It turned out that there was typical weed growth in the settlement area, whereas the field weeds that were found between the grains were only sparse.

Trees and forests

From the findings of the woody plants from well 1, 19 native tree species could be identified, which were present here around 230 to 250. Of these, beech, oak, hazel, various types of maple and fir were the most common. From a botanical point of view, there is therefore a clear picture of the Welzheim area in antiquity, when beech, oak and fir forests grew there, in which there was plenty of undergrowth of various other deciduous trees. Using the wood filling from well 1, the researchers also determine that the Romans mainly felled oak and fir wood (over 80 percent) in order to use it as construction and equipment wood. With only around 14 percent, these woods were followed by beech, which shows the clear selection of the Roman wood processors.

Compared to the material from the older well 2, which was closed around 190, it was found that at that time more oaks and firs grew in the region than when well 1 was abandoned, since the beech wood was more important there. Since the Romans did not appreciate the beech wood as much as the oak, they understood that there might have been a deterioration in the forest stand within around 40 to 60 years. This change may be due to the ancient timber extraction. However, this assumption does not agree with the percentages of juniper material from both wells. Since the juniper is a typical companion of the clearing, its population should rather increase over the decades. According to the findings, however, exactly the opposite should have been the case: Well 1 offered more material on this plant.

Further finds from the fort area

According to Hans-Heinz Hartmann (1995), the inventory of relief sigillates and stamps from the east fort was roughly doubled by more than 250 new finds. The old finds of the RLK are in the central archive of the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg (ALM) in Rastatt. Hans-Jürgen Eggers assigned a casserole dish to level B 2 or C 1 in the system he set up.

Troops and military personnel

A commander of the troops stationed in the east fort is known by name as the centurion of the 8th Legion, Marcus Octavius Severus . His votive stone was found in the rubble of the bathroom's heating system in 1894 and was probably reused as spoil. In addition to the Brittonen-Numerus, Marcus Octavius Severus also commanded an Exploratores unit that was stored here :

- I (ovi) O (ptimo) M (aximo)

- per salute (s) do-

- minor (um) Imp (eratorum)

- M (arcus) Octavius

- Severus | (centurio)

- leg (ionis) VIII Aug (ustae)

- preposit (us) Brit (tonum) et expl (oratorum)

Translation: Jupiter, the best and greatest for the good of the imperial lords. Marcus Octavius Severus, captain of the 8th legion "Augusta", Praepositus (head) of the Brittons and the reconnaissance.

The above-mentioned altar inscription from the period between 198 and 211 mentions the east fort as a garrison location of a unit of Brittones and Explorators . In the storage area has come out of the ground brick temple call a number Brittonum L ... or a number Brittonum Cr ... or Gr ... . A complete resolution of the abbreviations is not yet possible. The Numerus Brittonum L… was located in the east fort from 159/161 on.

Possible post-castle use

During their investigations in 1894, the Imperial Limes Commission excavated a 14-meter-long rectangular stone building, which is now indicated in its wall, which was located in the western part of the fort, on Ost-West-Straße. Here charred grains of grain were uncovered, which allowed the structure to be interpreted as a horreum , a storage building , although some of the architectural accents that are common for the military building type are missing.

The second stone structure that has been found in the weir system to this day is in the middle of the southeastern square of the storage area divided by two cross-shaped road axes. Due to the room design and the floor plan, it can be viewed as a Roman bath. The unusual location of the bath in the middle of the camp and the associated loss of space for the troops indicates, as the late antique bath in Eining Fort testifies, more to a post-castle construction and use. In the absence of more detailed investigations, speculation has already begun as to whether the abandoned camp after the Limes fall, in the late 3rd century, might not have turned into a villa rustica .

Vicus and burial ground

Between the west and east fort and on the south side of the west fort there was an extensive camp village ( vicus ) that had only been researched to a limited extent . Between 1955 and 1964, extensive traces of settlement with wooden and stone buildings were uncovered in the area northwest of the east fort.

Around 100 meters west of the north-west corner of the east fort, several graves were found during emergency excavations due to the construction of a sports field at the beginning of the sixties, but only inadequately recovered. When a sports hall was then to be built in this area, a total of 162 cremation graves from the 2nd and 3rd centuries were uncovered in September 1979.

South of the east fort, two Roman brick kilns were excavated in the Tannwald forest, and a Roman brick kiln about 170 meters south of the west fort.

The dense overbuilding that continues to this day makes comprehensive exploration of the vicus impossible.

Well finds

In the summer of 2011, traces of the vicus from the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD were also excavated on a garden plot in what is now the southern part of the city . Two wells lined with oak wood next to each other, whose moist environment has been preserved since antiquity, concealed a hoard of very well-preserved, mainly military bronze objects. The valuable pieces may have ended up in the wells during the troubled Limesfall period up to AD 260. Up until the time of discovery, the round medallion with a diameter of around 22 centimeters with a minerva bust that had been driven out was of particular importance, as it had no parallels in Baden-Württemberg. As a pectoral, the piece was part of parade equipment for a horse used in the military equestrian games and could be strapped to the chest of the animal via the middle strap distributor. Similar pieces with a Minerva head are very rare. One was discovered in present-day Iran , another also in Germany. The found material also includes a complete parade leg splint with a knee hump and a bronze plate. The second well contained a remarkably large bucket made of very thin bronze sheet, which was also in excellent condition, as it was probably used for mixing wine by a wealthy inhabitant of the vicus .

Monument protection and remains

The forts of Welzheim and the aforementioned ground monuments have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage as a section of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, the facilities are cultural monuments according to the Monument Protection Act of the State of Baden-Württemberg (DSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

Finds from the Welzheim excavations are now in the Welzheim City Museum, the Württemberg State Museum in Stuttgart and the Limes Museum in Aalen .

See also

literature

General

- Dieter Planck : Welzheim. Roman forts and civil settlement . In: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. 3rd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , p. 611ff.

- Dieter Planck: Welzheim. Roman forts and civil settlement . In: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart, Theiss 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1555-3 , p. 364ff.

- Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd Edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 .

- Philipp Filtzinger : Limes Museum Aalen . 4th edition. Edited by the Society for the Promotion of the Württemberg State Museum Stuttgart, Stuttgart 1991.

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . 4th edition. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2347-0 , p. 246ff.

- Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer , Andreas Thiel : The Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 .

- Sönke Lorenz, Andreas Schmauder: Welzheim. From the Roman camp to the modern city . Markstein, Filderstadt 2002, ISBN 3-935129-05-X .

West fort

- Dieter Planck: Investigations in the west fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg , 1989, pp. 126–127.

- Rüdiger Krause, Alexandra Gram: New excavations in the west fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis . In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2005. 26, 2006 ISSN 0724-8954 , pp. 129-134.

- Klaus Kortüm : The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . 4th specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission 27./28. February 2007 in Osterburken, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site, 3), pp. 123-139.

- Andreas Thiel: The defense towers of the west fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis. In: Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 1998. 20, 1999, pp. 94–96.

- Klaus Kortüm: The west fort of Welzheim - an almost unknown heavyweight on the Upper German Limes . In: Annual issue of the historical association Welzheimer Wald 14, 2010, pp. 5–60.

East fort

- A. Mettler, P. Schultz in the series The Upper German-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire . (Eds. Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey ): Department B, Volume 5, forts 45 and 45a (1904).

- Marcus G. Meyer, Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg, Klaus Kortüm: With ground penetrating radar to new knowledge about the interior development of the Welzheimer Ostkastell. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 2012 , 2013, pp. 170–173.

- Harald von der Osten-Woldenburg: Electro- and geomagnetic prospecting of the Welzheimer Ostkastell, Rems-Murr-Kreis. In: Archaeological excavations in Baden-Württemberg 1993 , 1994, pp. 135–140.

- Carol van Driel-Murray, Hans-Heinz Hartmann: The east fort of Welzheim, Rems-Murr-Kreis . Theiss, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-8062-1077-2 .

- Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 (research and reports on prehistory and early history in Baden-Württemberg, 14).

- Klaus Kortüm: Notes on the construction history of the east fort of Welzheim (Rems-Murr-Kreis) . In: Gabriele Seitz: The Provincial Roman Archeology in Freiburg. WS 1978/79 to WS 2005/06 . In this. (Ed.): In the service of Rome. Festschrift for Hans Ulrich Nuber . Greiner, Remshalden 2006, ISBN 3-935383-49-5 , pp. 257-266.

- Hartwig Zürn : The Roman citizen fort in Welzheim. Is it worth maintaining? In: Blätter des Welzheimer Wald-Verein 21, 1961, pp. 321–323.

Web links

- West fort and east fort of Welzheim on the side of the German Limes Commission

- Castles of Welzheim on Bernd Liermann's private website on antiquity

- Fortress of Welzheim on the website of the Central Office for Educational Media in the Internet e. V. (TO)

- Ostkastell Welzheim on the private Limes project page of Claus te Vehne

- City Museum Welzheim , official website

Remarks

- ↑ Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): Neue Forschungen am Limes , Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , pp. 123-124.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle. von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 313.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 321.

- ↑ a b c d Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 125.

- ↑ Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 137.

- ↑ Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 124.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , pp. 91-92.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 92.

- ^ A b Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 132.

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes . Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 92.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 152.

- ↑ Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , pp. 129-130.

- ↑ CIL 13, 06528 .

- ^ [1] Archäologisches Landesmuseum Konstanz, special exhibition 2007.

- ^ Dieter Planck: Restoration and reconstruction of Roman buildings in Baden-Württemberg . In: Günter Ulbert , Gerhard Weber (ed.): Conserved history? Ancient buildings and their preservation . Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0450-0 , p. 149.

- ^ Dieter Planck: Restoration and reconstruction of Roman buildings in Baden-Württemberg. In: Günter Ulbert, Gerhard Weber (ed.): Conserved history? Ancient buildings and their preservation . Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0450-0 , p. 150.

- ^ A b Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , pp. 92-94.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , pp. 92-93.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 96.

- ^ Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , pp. 96-97.

- ↑ a b c d Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany. 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , p. 94.

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 . P. 89.

- ^ A b Dieter Planck, Willi Beck: The Limes in Southwest Germany . 2nd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-8062-0496-9 , pp. 94-96.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: The Legions of Augustus . von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0886-8 , p. 205 f.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Horsemen like statues made of ore . Von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1819-7 , pp. 38/94.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Horsemen like statues made of ore . von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1819-7 , p. 26ff. and p. 88.

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 , p. 52.

- ↑ a b Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 , p. 74.

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 , p. 26.

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 , p. 44.

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 , p. 23.

- ↑ Udelgard Körber-Grohne u. a .: Flora and fauna in the east fort of Welzheim . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0766-6 , p. 73.

- ↑ Marcus Nenninger: The Romans and the Forest. Investigations into dealing with a natural area using the example of the Roman north-west provinces. Steiner, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-515-07398-1 , p. 206.

- ↑ Klaus Kortüm: The Welzheimer Alenlager. Preliminary report on the excavations in the west fort 2005/2006 . In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 136.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Eggers: Chronology of the Imperial Era in Germania . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Volume 5.1 . de Gruyter, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-11-006690-4 , p. 28.

- ↑ CIL 13, 06526 .

- ^ Dieter Planck: Welzheim. Roman forts and civil settlement . In: The Romans in Baden-Württemberg . 3rd edition, Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0287-7 , p. 617.

- ↑ Marcus Reuter : Studies on the numeri of the Roman army in the Middle Imperial period. In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission . Volume 80, von Zabern, Mainz 1999, ISBN 3-8053-2631-9 , p. 451.

- ↑ Ulrich Brandl, Emmi Federhofer: Sound + Technology. Roman bricks. Theiss, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2403-0 ( publications of the Limes Museum Aalen 61)

- ↑ a b Roman bronzes. Goddess from the well . In: Archeology in Germany 6 (2011), p. 5.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Riders like statues made of ore (= Antike Welt 27, Sonderh. 1 = Zabern's illustrated books on archeology . ), Von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1821-9 , p. 78/79 and p. 87 .