History of the Prussian Army

The history of the Prussian Army was marked by processes of change of varying intensity, as a result of which the Prussian Army was regrouped, realigned or fundamentally reformed in order to bring the armed power back into harmony with the newly emerged political and social conditions.

The fundamental evolutionary stages of the Prussian army were:

- Transition from the temporary mercenary army to the standing army approx. 1650 to 1680

- Professionalization, standardization, disciplining and institutionalization from approx. 1680 to 1710

- Expansion and maintenance of a first-rate army in Europe from approx. 1710 to 1790

- Replacement of the Army of the Cabinet Wars by a People's Army from around 1790 to 1820

- Restoration of the army as an instrument of rule and quasi praetorian guard of the king from approx. 1820 to 1850

- Transition to a modern mass army with industrialized warfare from approx. 1850 to 1910

Forerunner of the army

As early as the late Middle Ages , armies were temporarily set up for military campaigns. In 1420, Frederick I brought together 8,000 men in the siege of Alvensleben Castle not far from Magdeburg. When Albrecht Achilles in 1478 for a campaign against Pomerania-Wolgast equipped, he brought through the array 7,130 men, 2,000 riders and Lehnspferde of Roßdienstes and supplemented by Miettruppen and allies troops total 11,800 men together. In 1610 the castle guard, the electoral bodyguard, which had been in existence since the 16th century, was appointed with a strength of 70 men.

In addition, there was an older militia system and a national defense, the establishment of which was, however, bound to purely defensive acts and was also limited to its own territory. In the march, the Elector Johann Sigismund did not succeed in the years before the Thirty Years' War in creating a modern definition constitution that included, for example, a more rigid structure and command structure of existing teams. In the Duchy of Prussia , however, there was a defension plant around 1600. There were the institutions of the Wibranzen and the committee on the offices. In addition, there were practical exercises, arsenals and officers. After all, new fortresses were built in Küstrin, Peitz, Spandau and Driesen in the 16th century, where there were also gunsmiths and some garrison teams. The strength of mobilization in Brandenburg around 1600 was around 4000 men on foot and 1073 horsemen. The infantry contingent consisted primarily of members of the city. A contingent of rural dwellers had become seldom with the consolidation of the landlord's conditions as a result of the peasant war . Land surveyors recruited from the Netherlands began mapping the country. Armaments were purchased that should be sufficient for a contingent of 12,000 soldiers.

In the Jülich-Klevischen succession dispute , the Brandenburg Elector Johann Sigismund (Brandenburg) raised armed troops of around 4,000 men in 1609, including 1,000 infantrymen, the cities raised 2,600 men, and 400 horsemen completed the corps. These troops were supported for a few months at the expense of the estates. When the payments were not made, the units broke up again.

Under Georg Wilhelm I (1619–1640)

The Electorate of Brandenburg-Prussia developed into a state of European dimensions in the course of the 17th century. The territory stretched from the Memel to the Rhine. It consisted of the Duchy of Prussia , the Kurmark , Western Pomerania , the Archbishopric of Magdeburg , the Dioceses of Halberstadt and Minden , the Counties of Mark and Ravensberg and the Duchy of Kleve . From 1598 to 1648 it grew from 40,000 to 110,000 km².

The development of the military in early modern Europe was mainly influenced by the Orange Army Reform . This ensured a long-lasting restructuring of the late feudal army throughout Europe. In the 17th century, early absolutism set in in Central Europe , in which the sovereigns strove for absolute rule at the expense of the estates. The establishment and control of a standing army became an effective instrument of power for the territorial rulers, both internally and externally. At the beginning of the 17th century there were no visible signs of this in Brandenburg. The state had only grown considerably through recently acquired parts of the state in Prussia and on the Rhine and had not yet developed any central state institutions outside of the traditional and medieval institutions of the individual parts of the country. As everywhere in early absolutist Europe, state sovereignty was divided between sovereigns and estates under Georg Wilhelm 's government . Financing and constitutional law were closely related, the costly maintenance of the troops depended on tax revenue and the administrative structures required for this were lacking. As a result, there was also no functioning central defense policy. Instead, the regionally specific and centrifugal political forces held the political initiative in this dynastic ruling association and the central state forces in the fragmented state structure were weakly developed.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, the rulers only set up a paid mercenary army in the event of an acute war , which was disbanded immediately after the end of the war. This procedure, as the course of the Thirty Years' War showed , was no longer appropriate. The procedure for the sudden build-up of an army without regular troops required a long start-up time, the combat strength of the newly formed units was doubtful, as they were not trained uniformly. The possible level of performance in warfare by recruited troops was low overall and was well below the range of services available to the standing armies a century later.

While Brandenburg provided most of the military commanders in the Thirty Years' War, such as Hans Georg von Arnim-Boitzenburg , Georg Ehrentreich von Burgsdorff or Christian von Ilow , the administrative officials were not able to create a powerful army. Around 1618 the elector only had a small satellite guard for personal protection. It was not until the acts of war spread to northern Germany that mercenary recruitment began in Brandenburg . But the estates granted far too few resources to set up an effective defense of their own. Since the estates were not ready for long-term financing, Georg Wilhelm released the 1,300 recruited soldiers in 1621. The Berlin garrison, the Elector's two personal companies with 350 men and 152 horses, were reduced to 70 foot soldiers in 1623. By the mid-1620s, only 3,000 infantrymen and 500 horsemen had been drafted. However, they could not prevent the looting of the Mark by foreign armies. At the end of 1626, the elector moved his residence to Prussia, taking with him almost all of his troops totaling 4,500 men. He left only 900 men behind in Brandenburg, a number that was further reduced.

In 1631 the troop strength was 1,600 men in two regiments. After the Peace of Prague in 1635 there was an increase in the army at the instigation of Adam von Schwarzenberg. According to the minister's plan, a force of 25,000 men should be formed. The levies took place and the oaths of loyalty were made to the emperor and the elector. The generals of this army were Hans Caspar von Klitzing , Hildebrand von Kracht and Georg Ehrentreich von Burgsdorff. Klitzing, who was in command of this army, is considered the first general in Brandenburg. At the muster at Neustadt-Eberswalde in 1638 the army appeared with a strength of 8000 infantry and 2900 riders, but shortly afterwards it was again significantly reduced because the financial means for maintenance were lacking. Due to the lack of a strong military power, Brandenburg was threatened and its existence was endangered by external powers. Foreign armies crossed the country unhindered. Elector Georg Wilhelm I and his court had to flee from foreign troops several times.

Despite the small number of troops, 30 battles with Brandenburg troops took place in the Thirty Years War, mainly within Brandenburg until 1640.

Under the Great Elector (1640–1688)

drawing by Maximilian Schäfer

Transition from war to military

When the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm took office in 1640, Brandenburg was badly affected by the consequences of the war. According to the assessment of the overall political situation by Johann Friedrich von Calcum († after 1640), Brandenburg court marshal and prince educator, around 1640 the annexation of the Duchy of Prussia by Poland-Lithuania, the loss of claims to Pomerania and the control of Kleve by the Netherlands threatened. In the minds of contemporaries, the extreme excesses of violence of the mercenary armies and their difficult control by the sovereigns during the 30-year war had become permanently anchored. A disciplined and reliable armed force was necessary in order to restore Brandenburg's independence and to emphasize its foreign policy demands. The creation of such an institution became a main concern during the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm. The Elector thus followed a Europe-wide military boom . A comparable development began in almost all territories of the empire or the states of Europe. In the Holy Roman Empire, many of the imperial estates began to establish standing armies after 1648. This was made possible by the increased area of competence that they were granted as imperial estates in the Peace of Westphalia. Since the Peace of Westphalia , the jus armorum (Article 16, § 5), the right to maintain armies , has become a component of the sovereignty granted to the imperial estates , the jus territori et superioritatis . The jus armorum was now seen in connection with the law of alliances ( jus foederum ), which was also granted to the imperial estates in the Peace of Westphalia. In future, the sovereigns had to be able to guarantee the integrity of the territory by military means even in times of war. All imperial princes had to take a minimum of precautions for this. The accelerated professionalization of the military set a long-lasting innovation process in motion, which resulted in restructuring, a personnel policy, a clearer hierarchization, logistical precautions and uniformity that lasted well into the 18th century. Structures had to be built in order to maintain a larger number of soldiers in the long term. The many new tasks simultaneously meant an enlargement of the state structures and a consolidation of the sovereign rule. The dynamics of this period was described by historians in the 20th century as the Military Revolution .

Under imperial law, the establishment of a decentralized military system led to legitimation problems. Like the other imperial estates, the elector was not sovereign (like a king) and the imperial constitution made it possible to set up military contingents for the emperor as required and to establish a cooperative defense organization. In addition, a mercenary army could be used offensively and thus contradicted the defensive ties of imperial military power under imperial law. The way out was found in the Last Reichs Farewell of 1654 (§ 180) with the integration of the princely armies in the security policy of the Reich. From then on, the princely armies legitimized themselves as part of the imperial defense, as armed imperial estates .

Army strengths and recruitment

Around 1640 the elector had a number of troops with dubious loyalty to the ruling house, a total of 4650 - 6100 men, including 800 - 2500 horsemen. They had sworn on both the emperor and the elector and used this ambiguous double position to expand their own autonomy. The small troop that Adam von Schwarzenberg had set up was falling apart and there was no money to replace them. Open refusal of order by the regiment owners was a common occurrence. For example, the regimental commander, Colonel Hans von Rochow, threatened to blow up Spandau when he was sent an order that did not suit him. Shortly afterwards Rochow changed sides and signed on with the Kaiser. Right at the beginning of Friedrich Wilhelm's accession to power, the top thirteen army officers tried to blackmail the elector into paying a higher salary under threat that they would otherwise switch to the emperor as well. Under these circumstances, maintaining these troops was more dangerous than having them disbanded, which, moreover, could only be implemented with difficulty. An armistice with Sweden enabled a new start in army armament.

The concentration of the troops took place up to 2000 men. Almost the entire cavalry was left to the emperor. Mainly the elector's bodyguard and garrison forces were retained. To protect the neutrality of Brandenburg, a rearmament took place promptly. In a meeting of the Privy Council on June 5, 1644, the reinforcement of these rump troops and the establishment of a permanent army was decided. This should be paid for from the Elector's casket money .

The growth of the army required massive recruits in Brandenburg. The necessary numbers of recruits could only be raised with coercive measures. The suggestion for the first military recruitment came from the elector's advisor, Konrad von Burgsdorff . Each part of the country still had its own defense institutions and traditions, which hindered the development of a nationwide institution such as that of a common army. The recruiting undertaken for the new army brought together 4,000 men in Kleve alone. In the Duchy of Prussia 1200 regular soldiers and around 6000 militias could be raised. In the Kurmark the balance was much lower due to the decimated population. Only 2,400 soldiers could be recruited. Add to this the 500 musketeers of the elector's bodyguard. As early as 1646, two years after its establishment, the electoral army consisted of 14,000 men, consisting of 8,000 regular soldiers and 6,000 armed militias. After the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648, most powers began to reduce their troops. During the war-free years, the army in Brandenburg was reduced to a good half, so that the army's peace-keeping strength was more of a symbolic character and the remaining troops were just enough to cover the state fortresses, the position of some city soldiers and a bodyguard for the elector.

In 1651, when the elector advanced against Pfalz-Neuburg in the Düsseldorf cow war , the army already consisted of 16,000 men. However, since the war did not materialize, the majority were disarmed again in November. In 1653, the state parliament cut the elector's financial resources to such an extent that the troops had to be reduced. The body company on horseback and the body guard remained in place. There were still 1200 men in all garrisons of the Mark Brandenburg. In the other territories of Brandenburg-Prussia there were only 20 companies. In 1654 there was another increase in the army due to the threat of war with Sweden. In the Second Swedish-Polish War (1655-1660) the Brandenburg-Prussian army already reached a total strength of around 25,000 men up to 38,000 men including garrison troops, artillery and ten cavalry regiments. After peace was concluded in 1660, the army was initially reduced to around 12,000 men in order to relieve the financial burden. In addition to 34 garrison companies, there were now 5100 infantry and two dragoon companies 300 men strong. In 1666 the army grew again: seven cavalry regiments of 500 riders each, eight infantry regiments and two dragoon regiments emerged. In 1667 the strength of the field army was 8,200 men. In the year of the campaign in 1674 there were 15,400 men in the field, 5950 of them horsemen and 1150 dragoons. In 1679 at the end of the Northern War there were 21,033 infantry in 17 regiments, 4,178 garrison troops in nine fortresses, 3,454 dragoons in three regiments and two squadrons, and 9703 riders in 13 regiments and two squadrons. That is a total of 38,368 men, with land militias and artillery missing.

In their recruitment practice , recruiters were more cautious than before, but military qualifications were more decisive than aspects of loyalty when selecting personnel. Important generals of the first decades were Christoph von Kannenberg , Georg Adam von Pfuhl , Joachim Ernst von Görzke , Albrecht Christoph von Quast , all of whom moved from Swedish service to the Brandenburg army. Funds were allocated by the state treasuries according to certain rates for the advertising . There were also colonels who recruited soldiers at their own expense. This was especially true for individual squadrons and companies that acted as free companies as independent troops. Should a regiment be set up, a surrender was concluded with the colonel, stipulating the conditions for setting up the regiment , the level of salary , the cost of advertising, the advertising and model spaces and the time by which the formation of the regiment was completed should be. Was the troupe formed, it was patterned by a commission of three officers, a lieutenant general , a commissioner of war and a Government or district administrator . Every single soldier who was included in the sample role now had to prove his physical condition and material armament. If everything was found to be in order, the troops formed a circle and listened to the article letter with the flag waving, swore by the elector and then marched past the drafting committee with a sound of music. This examination was repeated every two years, and more frequently in times of war.

The increase in the army was not a linear, steady growth process, as the reinforcements of the 1640s were not permanent and sudden strong increases were drastically reduced again shortly afterwards, so that up to this point one has not yet from a completely standing army, but at most from can speak to a wavering army . However, the regimental cores around the officer positions remained from then on. The number of men in the regiments was then supplemented by advertising in the event of war . Ultimately, the institutional continuity caused the character of the units to change from the private company of the colonels to a kind of public-law institution. What seemed haphazard and irregular due to the short-term army structures could now be subject to a fixed rule and order based on the inner regimental cores and become a fixed tradition and thus regulate the formally permissible actions of the military actors more closely. Although in the 17th century 18 of the 60 infantry regiments of the Old Prussian Army listed in the main list of 1806 were set up, the continued existence of a regiment was not assured in this phase. Individual regiments were completely or partially abdicated and, if necessary, enlarged or reorganized. From the mid-1650s to 1688, over 75 regiments were formed and disbanded. The consolidation of the regiments into permanent military and social units was a long process.

Traditional elements alongside the small standing field army were also retained in the military constitution for a long time. So there were still fiefdoms and peasant militias who were called up to protect the country. However, this remedy was only used in particularly serious situations, such as when the Swedes invaded the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which had been stripped from the military, in 1674/1675. Likewise in 1661 and 1663 the Neumark liege horses were required by the elector. In the cities, too, their rights of defense are increasingly diminished. This concerned the fortification of the cities, the establishment of city armories or the position of city gunmen. These too were subjected to the new monarchical order.

Socio-demographic development

A kind of standing army gradually developed from the improvised troops of the 1640s and 1650s. However, this was still a mercenary army in character , which was recruited from soldiers of different origins. In 1681, out of 1,105 members of the team ranks, representatives from Prussia, Pomerania, Saxony, Westphalia, Silesia, the Mark, as well as 36 Danes, 83 Swedes, 47 Poles, 15 Bohemia, 8 Hungarians and others were enrolled in the Electress regiment . Such phenomena can be explained by the consequences of the war. The real goal of Friedrich Wilhelm, however, was to create a homogeneous army of regional children. Further socio-demographic characteristics of the troop structure around 1680 were:

- The bulk of the soldiers were between 20 and 30 years old.

- Individuals of the elders had served for up to 30 years.

- Very few were married.

- The professional background was basically a cross-section of the population, the soldiers came from all classes and professions.

- The accommodation in private quarters, mostly widely scattered in the countryside, made regular drill duty impossible.

- Some of the retired found a livelihood in the "Spandau Blessiertenkompanie".

Military operations

- Views of the Brandenburg Army in action

Crossing over the Curonian Lagoon in 1679

by Wilhelm Simmler around 1891“Landing of the Elector on Rügen”, Hermann Kretzschmer , oil on canvas Germany, around 1862

The decades after the Thirty Years' War in Northern Europe were a time of violent armed conflicts, which were primarily determined by Swedes. In this dangerous environment, the growing army of Brandenburg proved to be indispensable. Large parts of the army were therefore in the second half of the 17th century far away from their own territories in the European theaters of war at that time. Since the central continental position of Brandenburg-Prussia meant that the country constantly came into contact with the political intentions of the other European powers, state policy had to react to this regularly and avert threatening situations. In addition to the Swedish army , Polish , Ottoman or French armies were the opponents in the field at times . Led by the Great Elector personally, 8,500 Brandenburgers and 9,000 Swedes defeated 40,000 Poles in the Battle of Warsaw . This was the first time that the Brandenburg Army emerged as a military force in the European public. In this war, Friedrich Wilhelm obtained sovereignty in the Duchy of Prussia in the Treaty of Oliva in 1660 . This was followed by further war missions in the Turkish War of 1663–1664 in Hungary and in the Dutch War on the Rhine. Friedrich Wilhelm and his Field Marshal Derfflinger defeated the Swedish army in the Swedish-Brandenburg War in the Battle of Fehrbellin in 1675 . Subsequently, the electoral army drove the Swedes out of Germany and later from Prussia during the “ Hunt over the Curonian Lagoon ” of 1678. Friedrich Wilhelm owed his nickname “The Great Elector” to these victories.

In addition, significant individual military events in the period from 1674 to 1678 were: the battle of Türkheim , the Pomeranian campaign of 1675/76 , the Bremen-Verden campaign , the siege of Stettin , the battle of Warksow , the invasion of Rügen , the siege of Stralsund . While the army in the 1660s was used more as a contingent army and auxiliary of stronger armies, for example in Hungary in the fight against the Ottomans, its military value rose steadily in the observation of contemporary witnesses. As the general size of the army grew, so did the size of the troops that could be mobilized for a campaign . In the battles of the 1670s on the Rhine and in northern Germany, 20,000 combatants from the Brandenburg Army took part several times. In comparison, Western European armies such as the French, Dutch or Imperial armies reached combat strengths of 30,000 to 40,000 men in the battles of this time.

In the 181 years from 1626 to 1807 at least 4,000 combat operations with the participation of the Prussian-Brandenburg army took place. Among them were 270 sieges or defenses of a permanent place, which were distributed among 210 troop units of the main list of 1806. Until 1715, sieges prevail over battles and skirmishes. Later, fighting in the open air became more important. The regiments with the most fighting had the H 8 Hussar Regiment with 537 fighting, followed by the H 2 Hussar Regiment with 482 fighting and the H 5 Hussar Regiment with 395 fighting.

The army won the vast majority of its combat operations during this period.

Fortifications, general staff, tactics, training and equipment

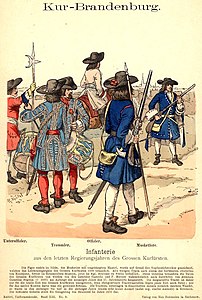

- Uniform studies based on drawings by Richard Knötel from 1675 to 1700

Satellite Guard around 1690, from 1692 Garde du Corps

The state established 24 permanent places on its territory , which maintained permanent garrisons under the army. These were in 1688:

- Altmark : Magdeburg Fortress ,

- Dominion Cottbus : Peitz Fortress

- Halberstadt Monastery : Regenstein Fortress

- Western Pomerania : Kolberg Fortress , Draheim Castle , Peenemünder Schanze

- Kurmark (here without Uckermark): City fortifications Frankfurt (Oder) , Fortress Spandau ,

- Neumark : Fortress Küstrin , Fortress Driesen ,

- Duchy of Prussia : fortress Groß Friedrichsburg , fortress Memel , fortress Pillau

- Uckermark : Fortress Loecknitz , Bärenkasten

- Westphalia : Altena Castle , fortress Duisburg , Fortress Hamm , Fortress Herford , Citadel Kalkar , Fortress Lippstadt , Fortress Minden , Fort Sparrenberg , fortress Wesel

In 1657 there were seven members of the General Staff . These were: General Field Marshal von Sparr , General War Commissioner von Platen , General Major Joachim Rüdiger von der Goltz , General Provisioner , General Adjutant Balthasar von der Goltz and General Adjutant von Brandt .

This was followed by a numerical expansion of the general staff. In 1675 the General Staff included a total of 28 army members, including Field Marshal Georg von Derfflinger, the cavalry general Landgrave von Hessen-Homburg , Lieutenant General von Goltz and Duke von Holstein, Major General Joachim Ernst von Görzke , Alexander von Spaen , Pälnitz, Götzen, Marcus from the Lütcke , Ludwig von Beauveau and Kurprinz, a quartermaster general , three adjutant general , a Generalauditeur, a general steward, a Council and Commissioner, a war commissioner, a Quartermaster General Lieutenant, one Generalauditeurleutnant, an army doctor , an engineer, a cashier , a field chemist , a Field shearers , a builder , a conductor .

By improving tactical training and arming based on the model of the French , Dutch, Swedish and imperial armies , the Brandenburg army was brought up to date with the latest European war technology. The pikes were retired and the unwieldy Luntenschlossgewehre the infantry were lighter, faster firing flintlock rifles replaced. A standard caliber was introduced for artillery so that field guns could be used more flexibly and efficiently. The establishment of a cadet school for officer recruits was an important step towards standardized training for officers. Better living and care conditions for soldiers and the disabled ensured a more stable command structure. These innovations also strengthened the cohesion and morale of the lower ranks. This can be seen in the low number of deserters in the 1680s.

The training took place according to Dutch and Swedish regulations. A first step towards the school education of the young officers was taken by the Knight Academy in Kolberg, which was set up in 1653 for up to 30 cadets .

One of the most famous representatives of these building decades at the end of the 17th century was the Upper Austrian farmer's son Georg von Derfflinger , who was promoted to baron and second field marshal of the Brandenburg Army. After joining the Kurbrandenburg Army in 1654, he mainly built up the cavalry as a separate branch of the army. He also influenced the development of a new soldier spirit that was no longer based on mercenaries and an efficient military administration. He shaped the officer corps by instilling an immaterial sense of honor and duty and a perceived duty of loyalty to the national service beyond military service . Another influential figure in the early Prussian army was the first Brandenburg General Field Marshal Otto Christoph von Sparr . This took care of the artillery and the pioneering. The cannons were heavy, immobile and inefficient. Above all, he reduced the large number of different calibers in the guns. In addition, he initiated the formation of a special artillery train, with which the mobility of the guns was increased.

Financing, administration and inner constitution

The traditional regimental order with a regiment chief as the owner of the unit and the unbridled Soldateska continued to work in the first decades after the founding of the standing army. Since state structures and supply institutions were only slightly developed up to the end of the 17th century, the principle of mercenary-based war entrepreneurship (regiment owners as private entrepreneurs on a lordly, governmental mandate) continued to apply after 1650 , according to which war is fed by war . Since there were no state utilities, the mercenary armies spread like swarms of locusts over the occupied territories, with no distinction between friend and foe. It was not the sovereign who was the leader of the army, but the general or colonel, who acted as military leader and businessman at the same time. Often having considerable equity, which he used to recruit and reward the mercenaries, he considered war a business. The colonel signed contracts with the warring sides independently, so-called surrenders, and he changed fronts when it was opportune. The contemporary descriptions of the Brandenburg regiment chiefs of that time conveyed only minor differences between an army colonel and a robber captain. This structurally independent mercenary system resulted in considerable disadvantages for the central government.

Many of the structural problems came from the management level of the army, the officer corps, and had to be remedied from there. Based on modern assessment criteria, the military level of the officers at the time was low. The officers and generals dueled one another, attacked one another, stabbed one another to death, without the elector being able to intervene effectively and a mutiny by the colonels could also pose a threat to the sovereign. The elector's debt to his colonels was also problematic. Due to the financial bottlenecks in the electoral fund, the colonels paid in advance in the event of war, for example in the Second Northern War. The elector could therefore not limit their autonomy. First of all, the elector wanted to transform the officers and generals from speculators and entrepreneurs into a loyal and conscientious troop. As a means of doing this, the electoral offices sought above all to withdraw from the colonels the privilege of filling officer positions and the autonomous judicial power within the regiments. The power struggle to fill the officer positions went through various phases. The colonels were keen to keep the right of appointment. In 1659 they were forced to include in the appointment documents the passage that they only dismiss their officers according to judgment and law. In 1672 the passage was added that it must be capable, capable, war experienced and loyal to the Elector people. The elector had at least one right of refusal. Only Friedrich Wilhelm's successor, Elector Friedrich III., Received the full right of appointment after the change of government in 1688.

The rulers in Germany countered the lack of discipline in the associations, the looting and violence against the civilian population by setting up their own administration and regulations. Up until then, the regiments were hardly controlled by the administration. This changed from April 1655 when two General War Commissioners were appointed to the troops to oversee the army's financial and material resources. One was Klaus Ernst von Platen , a nobleman from Brandenburg and the other Johann Ernst von Wallenrodt . Officials of this kind had already existed in the first half of the 17th century, with one crucial innovation. They were no longer tied to a regiment and instead acted as trustees of the individual territories. They paid attention to the salary, completeness and generally to the fulfillment of the capitulations of the colonels and captains in the interest of the sovereign. This system of local war commissioners developed into the central military administrative authority with permanent officials. A division of tasks developed between the Commander-in-Chief, the Field Marshal General and the War Commissioner General, which was not without tension because it curtailed the independence of the top military. After 1679 the responsibility of the General War Commissioner under the direction of Joachim von Grumbkow was extended to the entire territory of the Hohenzollern. It gradually took over the function of the estate officials, who traditionally supervised military taxes and discipline on site. Around 1688, when the Elector died, the General War Commissariat and the Chamber of Commerce were still relatively small institutions. However, these were expanded in the time afterwards and with their help the Brandenburg central state was further strengthened in relation to the state institutions.

As in all other armies, the ranking was not fixed from the start, but developed gradually, analogous to the removal of the regimental unit. In 1684 the decree followed that the rank is determined exclusively by seniority. The monarchical military legislation began to suppress the capitulations and to overlay the individual contracts with the colonels.

The long-term securing of the army's financing remained the most important building block on the way to the standing army. In Brandenburg there was no military entrepreneur like Wallenstein who could recruit troops on a large scale for his own account. The landed gentry themselves were affected by the general decline. Nobody could set up companies or regiments with equity. Therefore the elector remained dependent on the subsidies of foreign powers and the approvals of the estates. In order to preserve the army as the basis of foreign policy participation in peace, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm had to force the estates, which were opposed to the standing army and the national thinking that was first embodied in it, to maintain permanent garrisons and to grant tax permits. The estates had the largest share in the financing of the army, as they were entitled to tax permits. The elector had to laboriously wrest the payments from the estates at state parliaments . The standing army and the rights of the landed family ran against each other and yet were closely dependent on each other; for without security and without the protection of life and property no upswing could develop. In the traditional home state of Brandenburg, this succeeded without major problems. The regiments established in 1641 were only approved annually by the estates. In the state parliament decision of April 21, 1643, 118,000 thalers were earmarked for this. This procedure was continued until 1652. In the Diet meeting on August 5, 1653 succeeded the Elector in parliament farewell to get approved for a term of six years for the upkeep of the troops taxes totaling 530,000 taler annually. This essentially recognized the principle of keeping troops in peacetime. In fact, the institution of Miles Perpetuus (Standing Army) dates from this. Above all, the estates in Prussia caused problems. The Prussian estates leaned heavily on the Polish crown and oriented themselves towards the Polish nobility and their freedoms. The elector threatened military executions (similar to an imperial execution ) and marches into the duchy to enforce his demands. After the Königsberg uprising and with the use of force, the Prussian estates agreed to the new principles under the leadership of a central state and secure funding based on their own financial management structures. Only then was the permanent establishment of an army in Brandenburg-Prussia secured. With the introduction of the excise duty in 1676, more secure income could be generated, which flowed into the war chest. The estates had already lost a lot of their influence and the state parliaments were no longer convened.

Summary

The phase of the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm can be classified as a transition period to the system of absolutism, in which new structures were introduced in the army and the old ones initially persisted. During the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm, the army temporarily reached a peacetime strength of 7,000 and a war strength of 15,000 to 30,000 men. The army expansion was not linear and the traditional structures of the mercenary era continued to work. During the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm, the army became an important instrument in the transformation of the personal union of the Hohenzollerland into a real union and also in the implementation of the absolutist corporate state . In 1688 the military expenditure with an army of 30,000 men and a population of 1.1 million inhabitants amounted to 1.62 million thalers with a total national budget of 3.3 million thalers. The military share of government spending was therefore 50 percent. The Great Elector left behind an army based on the beginnings of a centralized military and financial administration. The first steps to integrate the nobility into the army were initiated. The officer corps consisted in 1688 of 1,030 officers, recruited mainly from the local nobility and about 300 Huguenot officers. The rights and opportunities for enrichment of the colonels, who appeared as autonomous military entrepreneurs during the Thirty Years' War, were drastically curtailed.

While the Brandenburg army was far behind the Bavarian or Hessian army in military terms around 1640 , around 1688 the army was the strongest in the empire after that of the emperor and roughly the same size as the Danish army . In summary, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm enforced essential principles of the Kurbrandenburg Army against the traditional order:

- Central personnel administration by the state via the appointed war commissioners

- Anciency principle for promotions

- state-owned pattern right

- sovereign military legislation on the Elector's office

Under Elector and King Friedrich I (1688–1713)

Hire the troops to England and Holland

In 1688 the successor to the Great Elector, Friedrich III. the government over Brandenburg-Prussia. The basic principles of the predecessor that had already been established were continued and little changed in the field of military organization during the reign of Friedrich I. Between 1688 and 1713 the state of Brandenburg-Prussia was at war with France, except for a four-year peace pause. The regiments fought in all theaters of war because the imperial estate was obliged to do so. At the beginning of the Imperial War with France in 1688 in the Palatinate War of Succession , Elector Friedrich III. For the first time it was suggested that in addition to recruiting by individual regiments, his local, Kurbrandenburg regional authorities within the Reich had to raise some of the recruits to replace men. Since then, the army team has mostly been supplemented by forcibly recruited "residents" and less by recruited "foreigners". After the Peace of Rijswijk , half of the army was released due to financial constraints. In 1701 Friedrich III crowned himself. to the "King in Prussia". As a result, his army was called "Royal Prussian" and no longer "Kurbrandenburg". In the course of the 18th century the name Prussia was transferred to the entire Brandenburg-Prussian state, both inside and outside the empire. The price that Prussia had to pay for the imperial recognition of the rise of rank was participation in the War of the Spanish Succession . Against the background of empty coffers, the ministers in Berlin operated an increased soldier trade in exchange for subsidies , which were added to the sumptuous court of Frederick as additional profits. The War of the Spanish Succession was a highlight of the subsidy policy. In subsidy contracts, the lending sovereign undertook, in return for a financial remuneration for a fixed period of time, which mostly extended beyond the duration of the war, to leave entire military units to another sovereign for free use within the framework of operations planned independently by the borrower. During the Spanish War of Succession, Frederick I divided his troops into the various theaters of war. 5,000 men were sent to the Netherlands and 8,000 soldiers to Italy .

The Prussian troops took part in the battles of Höchstädt , Ramillies , Turin , Toulon and Malplaquet , among others . The Prussian army suffered heavy losses , particularly in the battle of Malplaquet (September 11, 1709) and in the siege and capture of Aire on the Lys (Pas de Calais; September 12 to November 2, 1710). As a result of the long war phase, the Prussian provinces apparently hardly had any soldiers capable of military service. As a rule, no more recruits were recruited from the individual provinces, but the estates only made payments and the troops were raised by the military themselves or by contractually agreed takeover of entire units from other sovereigns. Individual parts of the army took part in a total of 56 battles during the war in Italy and on the Rhine front. The fighting strength of the army improved through the many fights. As an association, she learned different types of fighting such as fortress fighting. At that time, the Prussian troops already had a very good reputation. Prince Eugene therefore considered the Prussian infantry to be the best infantry in Europe.

Discipline and drill

The army's external impact changed drastically around 1700, away from a poorly disciplined and colorful troop towards a uniformly looking body in which all differences disappear. This was initiated by the overarching social transformation that is taking place , which is characterized by state-controlled, comprehensive social discipline. A multitude of disciplining tendencies set in, which no longer only had a superficial effect, but aimed at all areas of society and people themselves. The slowly developing political order should be enforced, and disciplined solidarity in the state should be created. The soldier should defend, the nobility should work, the subject obey, the civil servant unselfishly conduct the business of government and administration; man should conquer emotions with his mind. Everyone has to work.

In the process of disciplining society as a whole, Prince Leopold von Anhalt-Dessau, as head of the Prussian Corps in the War of the Spanish Succession, became an important player for the Prussian army. He played a similar role for the Prussian Army as Prince Eugen did for the Imperial Army. As an advocate of the infantry, he brought about a significant increase in the performance of his troops through a new drill and other organizational changes. The situation in the troops at that time was characterized by a general laxity of service in the noble officer corps outside of battle. These followed the image of the honnêteté homme from France. The officials from Prussia tried to enforce a different mentality and service concept. Instead of cavaliers , the officers should be functionaries, practitioners and drill masters. Due to the early autonomy of the regiment owners, the army's equipment was very different and each regiment drilled according to its own rules. Organized chaos was the result. In contrast, it was based on the contemporary idea that the soldiers should be formed into a disciplined body in which every shooter carried, loaded and fired his weapon with the same precision and speed. This uniform action in the unit was not yet firmly anchored and reduced the efficiency of the troop body in action. Standardization became the maxim of the reorganization of the Elector and Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau.

The introduction of the flintlock rifles and the replacement of the pile armies through the line tactics in the previous century increased the technical possibilities. The highest precision and speed of the loading process and a regulated drill step according to rhythm and speed became the most effective means of improving the combat strength of the infantry in battle. Prince Leopold introduced the iron ramrod (until then made of wood) around 1700 . The iron ramrod enabled faster and safer loading. First of all, Leopold developed drill regulations for his regiment around the ramrod , which became the basis for an army reform. The exercise now proceeded as follows. First, the grips were practiced. Then firing took place in trains and divisions. Then, while advancing slowly, firing was carried out in the same way, and also while retreating. A further innovation by Leopold, the lock step , was part of the smooth functioning of this “clockwork” . He ensured that all soldiers in a unit always maneuvered on the same level as their comrades and took their position in the formation at exactly the same time. Due to the particularly hard and intensive drill of the Prussian soldiers, they were capable of movements on the battlefield that would have disorganized other armies. Prince Leopold had also recognized that the rhythmic march made it possible to fire while moving. Leopold also introduced the concentrated peloton fire . The aim of the regular training measures in the Prussian corps was to achieve the absolute superiority of the thin infantry lines in combat against the enemy army line. Mobility and the rate of fire were checked by the officers with watches in hand. The training achieved that the rate of fire of the individual pelotons increased to three salvos per minute, while Austrian or Russian associations only got two shots per minute. The increased mobility and the rapid rate of fire enabled a change in tactics. If the rifle lines were previously deployed with up to six members, the Prussians reduced this to up to three companies. The Prussian drill had the effect that the soldiers were trained off every initiative of their own until they functioned like machines even under the greatest loads.

Prince Leopold von Anhalt received support in his efforts from Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, who traveled several times to the war zones and inspected the troops there. Both became friends. In contrast to the reigning king, who had the military system run by Field Marshal von Wartensleben , the Crown Prince and later King Friedrich Wilhelm was entirely military. Since then he has been active in the military and promoted the internal development of the army in the areas of training, uniforms and organization. When Friedrich Wilhelm visited the field troops on the theater of war in Brabant for the second time in 1709 , he had the infantry regiments practiced in the presence of the Allied Generals Marlborough and Prince Eugene, among other things according to the Dessau method. However, neither of them understood the sense of the future king's actions, who surrounded himself completely with his Prussian corps and continuously practiced drill grips and rifle grips. In 1729, King Friedrich Wilhelm I finally introduced Leopold innovations to the entire Prussian army.

In addition to the typical drill school that appeared, the military work that had begun was effective in all areas of army life from the point of view of standardization. In the first decade of the 18th century, everything was prescribed from above down to the smallest detail: clothing, equipment, the entire training and field operations, registration, warehouse regulations up to the setting up of the latrines and the maintenance of weapons. The officers were held responsible for compliance with the given orders. The soldiers were now dressed more uniformly. Uniform clothing brought several advantages: Firstly, the uniform filled the soldiers with a certain spirit of corps. Second, it was easier to distinguish between friend and foe. Thirdly, mass production made it cheaper to dress soldiers. In the Prussian army, blue was the dominant basic color. The first Prussian drill regulations were issued in 1702. Through such uniform reform work in detail, Friedrich Wilhelm and his supporter Leopold von Anhalt wanted to shape the troops into an absolutely compliant, uniformly functioning instrument.

During this time, the Crown Prince developed an army program, which he implemented after taking office. In addition to increasing the army, he wanted to eliminate the remaining deficit to the largest armies through better training. He developed the idea of Prussian administration and discipline into the Prussian drill . This became a tradition of the Prussian military system and the basis of the stereotype of the blindly obedient Prussian soldier.

Military justice

The early modern military justice system as a special justice system consisted of the

- Jurisdiction or the court martial and the

- Martial law and military legislation together.

In the 17th century, a distinction was made in military court proceedings between lower or regimental court , garrison court , court martial, and higher or general court martial . The sovereignty of the regiment was still with the regimental colonels and not with the sovereign, the elector.

There was an electoral Brandenburg martial law since September 2, 1656, which was renewed in 1673. However, no court order was issued. Until 1712 there were no uniform provisions on martial law, only a customarily developed court system and rules of procedure. In 1712 Frederick I issued a court martial order.

With the electoral ordinance of April 27, 1692, under the supervision of Eberhard von Danckelmann, a military court was established for church affairs of the military. The spiritual military tribunal remained independent of the military leadership and strengthened the electoral control over the army by a further instance. In addition to basic regulations, it laid down written instructions for the field preachers to deal with the soldiers. As an independent supervisory authority, the consistory was responsible for ensuring that the contents of the articles of war (military laws) were actually observed by the soldiers and that the soldiers' discipline was increased. The military jurisdiction of the army significantly increased social militarization. The courts-martial had jurisdiction not only for the "enrolled" not yet drawn, but also for the families of the soldiers and the servants of the officers. In the cities, a large percentage of the population was encompassed by martial law.

The war articles of the Swedish kings Gustav II Adolf from 1621 and Karl XI. from 1683 were considered progressive, so that many sovereigns, as well as the Elector Friedrich Wilhelm in 1656, took the early bureaucratic structure of Swedish military law as a model. The war articles or article letters of September 2, 1656, with modifications, were valid for around 200 years in Brandenburg-Prussia and served as the basis for Prussian military penal legislation , but since Friedrich Wilhelm I only for NCOs and men . The three subsequent modifications to the Prussian article letters were made in 1673, on July 12, 1713 and August 31, 1724, and by 1870 seven further modifications followed. In the modification of 1673, the Brandenburg martial law comprised a total of 19 titles and 91 paragraphs. According to Section 91 of the Brandenburg Articles of War of 1673, all articles of war had to be read out to each regiment every three months. In 1712 a court martial was introduced. As with the war articles, this was based on the Swedish model, the general and higher court order. The service regulations of March 1, 1726 were added as the keystone of military law . These regulations contained the laws on officers, while the articles of war from then on only applied to men and non-commissioned officers.

More Electoral royal regulations dating from about 1670-1720 concerned the Verpflegungsordonnanz , a Einquartierungsreglement , a Enrollierungsreglement , the establishment of a rank and Quartier list, carriage rules of generals, a march edict, a new pattern of order, a Uniformierungsregelung, advertising bans foreign armies and so on . The General War Commissariat had in the meantime gained the greatest influence and decided itself in the officers' personnel matters, while the generals had no influence on the internal development of the army until 1700.

Army size in comparison

When the king died in early 1713, the army had grown to 40,000 men with a total population of 1.6 million. At this time there were five regiments with almost 4,000 men in Anglo-Dutch wages.

The army had increased tenfold from its establishment as a standing army in 1644 to 1713. Most of the other powers have also greatly increased their army strength during the period. Internationally, the absolute wartime strength of the army was not very strong in comparison with the other top armies in Europe in 1710. The Prussian army (figure number 1) approached or exceeded numerically the height of the (Saxon) - Polish crown army (figure number 11) in times of war, the Danish-Norwegian army (figure number 9), the Janissaries of the Ottoman Empire ( Figure number 10), the Portuguese Army (Figure number 12) and it also approximated the strength of the Spanish Army (Figure number 8). The Swedish army (figure number 6), the Russian army (figure number 3), the English army (figure number 7), the Dutch army (figure number 4), the imperial army (figure number 5 ) were significantly stronger ) and finally the strongest army on the continent, the French army (figure number 2) which was around nine times the size of the Prussian army. In purely numerical terms, the Prussian army was the 11th largest army on the continent. The growth of the armed forces in Europe continued throughout the 18th century, with the Prussian army clearly catching up with the top armies by the middle of the century and henceforth to be one of the strongest armies.

During the 25 years of Frederick I's reign, the army continued to consolidate its structures. During this time, the army gained considerable external reputation due to its innovative training system, which accumulated in a significant increase in performance compared to the other armies.

Under the soldier king Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713–1740)

The army acquired particular importance during the reign of the soldier king Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713 to 1740). The army enjoyed priority in the emerging Prussian state , which would be unthinkable without an army. When he took office in 1713, Friedrich Wilhelm changed the ranking table drastically and privileged the military dignitaries over the civilians. Instead of the abolished civilian chief chamberlain , a field marshal now led the table. He was followed by the governor and the infantry generals . From then on the king wore only uniform. On March 4, 1713, the militia, which had a strength of 7,767 men, was disbanded. The militia, which only drilled weekly on Sundays and therefore hardly passed as a military unit, had not complied with Friedrich Wilhelm I.'s military views. In terms of fashion, a deep cut followed the practice of its predecessor. In 1713 the king introduced the soldier's pigtail as compulsory fashion for his army and forbade the wearing of the allonge wig that his father still wore.

During his time as Crown Prince, Friedrich Wilhelm worked out his basic principles of governance. Under the leadership of his father, Prussia was a European middle power that could not pursue an independent foreign policy and could only maintain its army against aid from other powers. Maintaining the army with its own means, Friedrich Wilhelm's central state purpose, was only possible through the restructuring of his own state. With the death of King Frederick I, his successor slashed the entire household and reduced the cost of keeping the court to a minimum. The funds released were instead given to the army for maintenance. This in turn meant that after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession and the discontinuation of subsidy payments, half the army no longer had to be reduced, as all other European powers did afterwards. The Prussian army personnel could be increased by seven regiments between 1713 and 1715 due to financial inflows from the savings of the other departments. The reinforcement happened according to the principle of free advertising , so that each regiment acted on its own and partly covered its recruitment needs through illegal fraud. This approach ensured that the need for recruits was met quickly, but at the same time led to a mass exodus of the population fit for duty to “nearby countries” and to an increase in the desertion rate . In order to counteract the bloodletting of the population and economic power, a large number of measures were used. At first the king tried to counteract the development by threatening to punish the refugees. But that brought no improvement. On May 9, 1714, the king introduced general service for all young men by decree . At least de jure, this meant that there was general conscription . However, this remained impracticable because the level of development of the early modern state was still too low and the feudal-class society was overburdened. In order to limit the desertion rate, official bodies increasingly issued vacation permits for those who were obliged to attend. This actually brought improvements from the mid-1720s. Little by little, the responsible authorities stopped using domestic advertisements. Instead, more and more advertising was carried out abroad that covered 30 percent of the recruitment requirement. Areas affected were the other states in the Holy Roman Empire, Poland, Russia, Southeastern Europe and Ireland. The other states resisted Prussia's actions and issued advertising bans. The people were expressly requested to ring the storm bells when Prussian recruiting troops approached. Kurhannover issued the following ordinance on December 14, 1731:

"Prussian and other advertisers ... should be beaten as road robbers and human robbers, disruptors of the peace and violators of our Highness and, if found guilty, punished for life. ... Whoever delivers a Prussian advertiser dead or alive receives fifty thalers from the Kreigskasse. "

In Germany, the recruits began to enter all men fit for service in regionally specific lists (“to enroll”) and to recruit only some of them if necessary. From this a legally binding recruitment system, the so-called cantonal regulations , developed through various royal ordinances in 1733 , which was to last until 1814. The aim was to end the army's often violent recruiting. The cantonal regulations forced all male children to be registered for military service. In addition, the country was divided into cantons, each of which was assigned a regiment from which it recruited conscripts. The period of service of a cantonist (conscript) was usually two to three months a year. The rest of the year the soldiers were able to return to their farms. Urban citizens were often exempt from military service, but had to provide quarters for the soldiers.

The expansion of the army continued in the period that followed. In 1719 there were already 54,000, in 1729 more than 70,000, in 1739 over 80,000 men, including 26,000 recruited foreigners. (For comparison: in 1739 Austria had 100,000 men, Russia 130,000 men, France 160,000 men under arms). Since the armies of the other powers had significantly decreased between 1713 and 1740, the growth of the Prussian army weighed heavier. The general disarmament efforts were based on a stable balance of power in Europe, which resulted in a relatively peaceful period. Prussia was "as a dwarf in the armor of a giant". In the ranking of the European states in 13th place, it had the third or fourth strongest military power. Overall, Prussia spent 85% of its government spending on the army at this time. In comparison, the army expenditures of the other powers were around 40 to 50 percent of government expenditures. Of the total income and expenditure of the Prussian state budget, which amounted to around seven million thalers in 1740, five million thalers were used for the army and the remainder was used to cover the costs of keeping the court and administration. Up to 1740, a war treasure of eight million thalers had been collected from the savings. What was still lacking in equality with the great power armies was made up for by the quality of the training.

In the peace that followed from 1715 to 1740, the army was spread over the urban citizen quarters and was supported by the municipal excise and property taxes. Due to its mass demand for food, clothing and equipment, it became the largest consumer and employer in Prussia. The armaments industry was also expanded to supply the army with weapons and equipment. Among other things, the Royal Prussian Rifle Factory and the Royal Warehouse were built as important production centers. If the army was mobilized, the economic cycle was immediately interrupted, tax payments fell and the army had to be supported by the war treasure. Due to these interactions, the king avoided being drawn into armed conflicts, so that the Pomeranian campaign of 1715/16 was the only war effort of the army in the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I.

The royal regiment of the Lange Kerls in Potsdam served as teaching and model troops . This regiment originated from the soldier's hobby of the "soldier king". The king had recruiting officers sent out in all directions in Europe in order to get hold of all the tall men over 1.88 meters there were. This king's passion for “tall guys” had a practical sense, as they could use feet with longer runs. The ramrod could be pulled out of the muzzle loader and inserted more quickly. This allowed them to shoot more accurately and further in battle. A decisive advantage over other armies. The regiment consisted of three battalions with 2,400 men. The Lange Kerls were a pictorial expression of the well-managed army and the soldier's raison d' etre under Friedrich Wilhelm. At the same time, the army embodied the drastically changed relationship in Prussia to absolutist reputation and symbolism of rule , away from the court of law and towards the effectively controlled military state . The Prussian soldiers therefore served the king to represent the Prussian monarchy. Instead of courtly grandeur and festivities at state receptions, the military often played the central role at princely receptions on official occasions. The program included a tour of the giant guard, several revues , artillery shootings and a visit to the Berlin armory. Also maneuvers with terminating a parade among the official events. Occasionally there was also the ceremonial handover of a regiment.

In the course of the ongoing development of the absolutist central state, the aristocracy was increasingly deprived of its political rights from the medieval estates . In return, he received greater economic independence and was tied to the monarchy through the army officer corps . Since the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I, the officer corps consisted essentially of members of the nobility . This was unique in Europe. Although the officer corps in Austria, France, Sweden and Russia were predominantly nobility, almost all officers in Prussia came from the local knighthood. However, he had to be systematically forced to join the army. Friedrich-Wilhelm I also forbade the nobility from serving in an army other than the Prussian army. The proportion of nobility fluctuated considerably between the individual regiments or branches of the army. In the light troops like the hussars there were considerably more officers of bourgeois or peasant origin than in the old and prestigious field regiments. Furthermore, he issued an order that the nobility had to give their sons between the ages of 12-18 years for training and education in the newly created cadet corps . Under his reign, a fifth of the offspring of officers were recruited from the cadet houses. The cadet corps not only served to prepare for officer service, but also had a strong social component. Unprofitable nobles could have their sons cared for here. Thus the nobility, like the simple peasants or bourgeoisie, was made subject to service. In principle, long-serving and particularly proven non-noble NCOs were appointed officers in peacetime only in exceptional cases. As a result of this recruiting practice, regular military dynasties developed in the course of the 18th century, with individual families serving in the same regiments over and over again. In terms of numbers, the officer corps developed as follows in the 18th century:

| year | 1713 | 1720 | 1733 | 1740 | 1755 | 1786 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of officers | 1163 | 1679 | 2148 | 2523 | 4276 | 5511 |

In the course of the steady expansion of the army in the 18th century, the number of officers required also increased. Although Friedrich Wilhelm I went down in history as the soldier king, he led his army into war only once during his entire term of office, namely during the Great Northern War in the siege of Stralsund (1715) .

King Friedrich Wilhelm enforced essential principles of the Prussian army:

- Connection of the advertising system with the compulsory service of local farmer sons,

- Recruiting officers from the local nobility,

- Financing of the army through the electoral domain income , through the compensation payments of noble feudal obligations and through taxation of the cities.

Since the time of the soldier king, contemporaries have recognized the Prussian army with accuracy, eagerness to serve, obedience, a sense of duty and efficiency. In a negative sense, stereotypes arose on militarism, warmongering, barbaric penal systems and callous manners.

Under Frederick the Great (1740–1786) until the defeat of 1806

Operations in the First and Second Silesian War

Friedrich Wilhelm I's successor, Frederick the Great (1740–1786), took over an almost perfectly organized army from his father. During the course of his reign, the son continued his father's system of privileges for the army, except for a few war-related modifications. As a result, the needs of the armed forces continued to be put at the forefront of state efforts and all other non-military needs were put on hold. Absolutism reached its peak in the first decades of Frederick's rule. The Prussian landed aristocracy , which was transformed into a service aristocracy and was designated as a reservoir for the officers' corps, had a stabilizing and conserving effect on the Prussian military system . Officers with land ownership became the exception and the aristocrat who relied on royal service became the norm. This resulted in a double dependency of the nobility, which could only maintain its influence in this loyalty system and changes threatened its leading position in society. The king had set up formal class barriers that prevented the social classes from being mixed up. In this social system geared towards the king, there were landlords and officers on the one hand, and landlord and cantonist on the other. The result of this entangled class policy was the subordination of all civil society positions to the military staff with a simultaneous increasing tendency to freeze in further social development. As Frederick II's reign increased, this system survived. The background that moved the king to develop this rigid social system under the leadership of the officers' corps was his foreign policy maxims, to which he subordinated everything else. It was therefore important to maintain and enlarge Prussia as a state in competition with its neighbors.

Immediately after taking office, the king continued the increase in the army operated by Friedrich Wilhelm I and increased the troop strength to almost 90,000 men. Half a year after the accession to the throne, the Silesian Wars and, from a European perspective, the overarching War of the Austrian Succession began . The Prussian army invaded the Habsburg province of Silesia . Under the leadership of Field Marshal Kurt Christoph von Schwerin , defeated the Austrian troops on April 10, 1741 in the Battle of Mollwitz and thus decided the First Silesian War in favor of Prussia. But the victorious battle also revealed the army's weaknesses. In the battle, the monarch and troops showed the shortcomings of a lack of practice and peace training acquired on the parade ground. A lack of overview on the part of the commanders and panic in the regiments brought the Prussian army dangerously close to defeat. Only the triumph of the drill over fear in the Prussian infantry turned the tide at the last minute. The battle had demonstrated the inferiority of the lumbering Prussian cavalry. As long as it was unable to carry out offensive operations, the king lacked the most important element of agile warfare.

Frederick II used the brief period of peace between the First and Second Silesian Wars (June 1742 to August 1744) for critical reflection on the events of the war. He processed his findings on June 1, 1743 in textbooks and instructions for the cavalry and infantry. In 1743 the king established the practice of autumn maneuvers, in which combat situations were simulated. His father had carried out general revues every year since 1715 . These usually took place northeast of Magdeburg , between Pietzpuhl and Körbelitz ; The king dismounted in the Pietzpuhler Schloss for these army shows and large-scale maneuvers by the Prussian army. A display board on the Schanzenberg and the replica of the earlier memorial on the Schanzenberg in Körbelitz reminds of these troop revues, which took place up to the Wars of Liberation ; the Körbelitz firing range was used for military exercises for 300 years. Special revues also took place in the spring, but were not held under combat conditions. At the special revues only a single regiment was mustered by the king, at the general revues large units of troops.

The regiments had to maintain full strength during the revues and those on leave had to be present. New tactics were tried and the king devised particularly complicated maneuvers. In the Spandau maneuvers in 1753 , 44,000 soldiers were drawn together. This caused an uproar throughout Central Europe. Foreign observers were not allowed. So it was difficult for foreigners to decide whether it was a big maneuver or a mobilization . These maneuvers before the Seven Years' War made a significant contribution to increasing the strength of the troops. Mistakes in the review could easily lead to outbursts of anger on the part of the king and end a longstanding officer career that had been successful up to then, depending on the king's mood. Regiments that suffered a setback in the war found it particularly difficult to survive a troop revue afterwards. The ceremonial aspect of the revues tied the army to its king. In the later years of the reign, the king appointed inspectors who partially relieved him. They went to the regiments assigned to them, checked their condition and reported to the king.

In addition to training the cavalry, he was particularly concerned about increasing the number of hussar regiments that were responsible for exploring the terrain and reconnaissance. During the two years of peace, the Prussian army grew by nine field battalions, 20 squadrons of hussars (including 1 squadron of Bosniaks ) and seven garrison battalions . The new Prussian province of Silesia added eight more fortresses to the Prussian fortress belt. These were the fortress Glogau , Breslau , Brieg , fortress Cosel , fortress Neisse , fortress Silberberg , fortress Schweidnitz and fortress Glatz . The duties of the general staff during the war were limited to engineering services and the king was consequently his own chief of staff . The officers, like the adjutants, were personally assigned to the king and, as the supreme warlord, he did not need any independent organization, only vicarious agents.

Austria tried to retake Silesia in the Second Silesian War . Like the first, Frederick began the Second Silesian War with a rapid advance into enemy territory. However, the campaign of 1744 was catastrophic for Prussia and ended in an almost complete dissolution of the army. The king had strayed too far from his supply lines, and supplies from the occupied territory also failed. Without having fought a battle, the Prussian army lost almost half of its men to capture, desertion, or illnesses caused by deficiency. In the next year of the campaign the tide turned. Austria and Saxony were defeated in the Battle of Hohenfriedeberg in 1745. Especially the hussars (also called Zietenhusars) under the leadership of General Zieten were able to distinguish themselves in this battle. The successes at Hohenfriedberg, Soor and Kesselsdorf were achieved thanks to an improved fighting style of the cavalry as well as the precision and swing of the infantry regiments. The total losses of the army in the Second Silesian War amounted to 14,000 men.

Interwar years

The years that followed until the war broke out again were a time of targeted expansion of the army. By 1755 the total strength of the Prussian armed forces had grown to 136,629 men and by the beginning of the Seven Years' War to 156,000 soldiers. The war experiences were used in the army to increase the efficiency of the troops as a whole through measures of reorganization and organizational development. The cavalry class of troops was constantly changing and improving its efficiency. From a deficient troop, as it was still perceived in the first Silesian War, it became a powerful support of the infantry in the Seven Years' War. The main reason for change was the presence of capable leaders. In addition to Zieten, Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz stood out among the cavalry . According to the judgment of English and French military historians, he was next to Joachim Murat the most important equestrian leader in modern war history. In addition to his successful leadership of large cavalry groups such as B. in Roßbach (1757) and Zorndorf (1758) he is considered the creator of modern cavalry. His principles for training on horseback and in combat continued to apply until the First World War. The first two Silesian Wars also showed deficiencies in field artillery . In the period that followed, new units were built and the number of field guns more than tripled from 222 in 1744 to 723 guns in 1763. In 1763 the combat strength of the Prussian artillery was 6,309 soldiers.

The Prussian magazine system was greatly expanded in the 18th century. The food allocations per soldier were initially two pounds of bread and two pounds of meat per week, but in 1746 the ration was reduced to one and a half pounds. At the beginning of the Seven Years' War Prussia had 32 war magazines in which almost 80,000 pounds of grain were stored. 120 field preachers in the army provided spiritual support. During the First Silesian War, the reserves of the war treasure were sufficient for maintenance. During the Second Silesian War, the reserves were completely drained and additional loans were necessary. The war treasure, which served to maintain the army, was quickly replenished after 1744 and amounted to almost 18 million Reichstaler at the beginning of the war. This reserve was sufficient for about a year of active warfare. The expenses were made for mobilization, replenishment of the magazines or the formation of field war coffers.

Operations in the Seven Years War

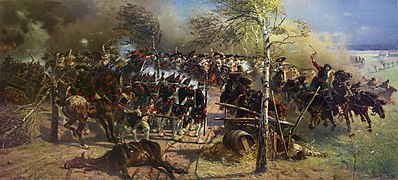

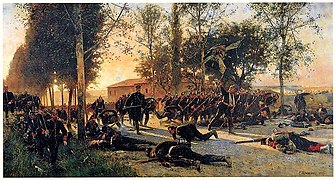

- The Prussian Army in the First and Second Silesian War

The Prussian troops in the battle of Mollwitz in 1741

The Battle of Hohenfriedeberg on June 4, 1745. Prussian grenadier battalions defeat the Saxon Guard. Carl Röchling. Military History Museum of the Bundeswehr, Dresden

Battle of Hohenfriedeberg, attack by the Prussian Grenadier Guard Battalion , June 4, 1745, historical painting by Carl Röchling (1855–1920)

Copy (by Otto Rose, 1911) of the picture by Carl Röchling († 1920): Friedrich II. In the battle of Zorndorf 1758. Oil / canvas. 82 × 115 cm

Storming of the ramparts by Prussian troops in the Battle of Leuthen in 1757, Carl Röchling († 1920)

In the 1750s, the foreign policy climate changed again. Austria allied itself with France in the course of the diplomatic revolution (1756); Austria, France and Russia stood together against Prussia. Frederick the Great attacked his enemies preventively, which triggered the Seven Years War . Although outnumbered, the Prussian army achieved notable victories in 1757 in the Battle of Roßbach and the Battle of Leuthen . In contrast, the Prussian forces were clearly defeated in the Battle of Kunersdorf in 1759 . Contrary to its own guiding principle of avoiding wars of attrition at all costs and instead gearing everything towards a quick offensive war decision, the Prussian army had to fight the war of attrition, which it was less able to endure due to its limited resources compared to the enemy. Due to the losses, it was not possible to maintain the number of employees. The winter campaigns of 1759 and 1761 alone resulted in as many casualties as several battles as a result of illnesses and frostbite. The Seven Years War resulted in casualties in the Prussian army between 142,722 and 186,000 men. The army lost another 80,000 men through desertion. (Austria: 62,000 men, France: 70,000 men). The army had to be practically reorganized in the course of the campaigns, with the loss of substance over time being greater than the addition of new forces to the army. In particular, recruiting with foreigners was only possible to a limited extent in times of war and this reduced the potential for recruiting. The demands on the quality of the replacement had to be constantly reduced. The battles were much more intense and more frequent than in the 17th century. In the campaign year 1757 alone, the Prussian army carried out 188 combat operations (September 3, 1756 to December 31, 1756: 39 battles). In 1760 there were 296 battles, in 1762 there were 204 combat operations. On average, there were around 200 battles per year, adding up to the entire conflict, this is around 1250 combat operations by the Prussian army from September 1756 to the end of 1762. In addition to the many vanguard skirmishes or reconnaissance battles , there were only a few dozen main battles that were decisive for the campaign. Of these 21, according to the record of Frederick II's main battles, the Prussian army triumphed in 14, while seven were lost.

With dwindling physical reserves, small warfare in particular became increasingly important. In order to be able to compensate for the superiority of the Austrians ( border guards , Pandurs ) and Russians ( Cossacks ) here, Friedrich set up free battalions (“Three blue and three times the devil, an exekaberes shit!”) And even attacked the military with the formation of militia units Development of the Wars of Liberation .