Prussian invasion of Holland

The Prussian invasion of Holland is a military intervention by Prussia in the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands in 1787.

prehistory

causes

Tensions between governor and regent

The United Provinces of the Netherlands at the end of the 18th century

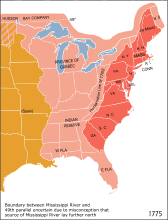

British colonial empire on the American east coast; the Thirteen Colonies (red), Province of Quebec and Indian Reservations (pink)

Kingdom of Great Britain late 18th century

The Republic of the Seven United Provinces (see figure above left) was marked by great internal political tensions at the end of the 18th century: the American War of Independence (1775 to 1783) threatened to split the country. The governor Wilhelm V , a grandson of George II , stood on the side of the British monarch, whom he saw as having the right to put down the rebellion in the Thirteen Colonies (see figure above in the middle). The so-called regents, the urban ruling class, on the other hand, sided with the American colonies; from the Caribbean island of St. Eustatius , they supplied weapons and ammunition to the independence movement, which was allied with the Kingdom of France , Great Britain's arch-rival. This, and the treaty between the American and Dutch Republicans formulated in 1780, provoked the Kingdom of Great Britain (see illustration above right) to declare war on the Seven United Provinces in December 1780. This began the so-called Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780 to 1784).

Consequences of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

The condition of the Dutch navy was backward and so the naval war against the Kingdom of Great Britain was decided in a very short time. The consequences of the Treaty of Paris in 1784 were devastating for Amsterdam , as Great Britain could now claim Dutch possessions on the east coast of India. The United East India Trade Company collapsed due to the trade provisions of the Paris Treaty. Since the Republic of the Seven United Provinces even had to agree to the free passage of British ships through all areas ruled by the republic, the sources of Dutch economic power dried up; worldwide shipping and trade with the colonial empires in the New World and Asia. The economic decline finally cemented the domestic political tensions and finally brought about a third political movement in addition to the heir and regent; that of the so-called patriots .

Movement of the Patriots

The movement of the Patriots originated in 1784, the so-called "catastrophe year" of the Treaty of Paris. The patriots demanded, on the one hand, that the inheritance holder restrict his de facto monarchical privileges and, on the other hand, that the regent families have more say in terms of representative democracy. The bitterness over the economic consequences of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War ensured that the patriot movement came closer to France than Great Britain. With French help, the British influence should be pushed back. However, this also meant deposition of the inheritance holder, Wilhelm V, who was supported by the British. It began to become apparent that the decision to keep the inheritance office could trigger a civil war in the Netherlands.

Development towards the danger of civil war

Military clash

In 1785 the States General , an assembly of estates of the provinces, revoked the inheritance holder's authority over the regular land forces . Due to a loyal following and thanks to British aid payments, Wilhelm V was nevertheless able to set up a considerable private army. But also the cities of The Hague , Kampen , Zwolle , Zutphen and Harderwijk, controlled by the patriots, sent soldiers. Although Wilhelm V's troops were able to prevail in the fighting for Elburg and Hattem , the overall situation was by no means decided. In 1786 Wilhelm V was deposed as captain-general of Holland and inheritance holder. If Wilhelm V wanted to regain his position, he had to rely on the military support of his brother-in-law, King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia . Wilhelm's wife Wilhelmine was the sister of the Prussian king, a military leader of 195,000 soldiers.

Stay of Wilhelm V at the court of Friedrich Wilhelm II.

Wilhelm V left the soil of the Seven United Provinces in October 1786 to travel to the Prussian capital Berlin. Although he had already written to Friedrich Wilhelm II's predecessor, King Friedrich II of Prussia , he had only responded with recommendations and advice, not with troops as Wilhelm had hoped. King Frederick II had hoped to the last to be able to approach France, which supported the patriots. King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia also wanted to continue this "policy of détente" towards France. He could see no advantage for Prussia in being drawn into a war between Great Britain and France. After all, France had only recently decided the American War of Independence. Friedrich Wilhelm II was also aware that in the event of a Prussian intervention Wilhelm V would severely punish his political opponents - which would not contribute to the long-term stabilization of the Netherlands. Wilhelm's bad reputation could also ruin the reputation of the Prussian army. Friedrich Wilhelm II. Received Wilhelm V, but could not be changed by him. Instead, the Prussian monarch ordered his Minister of War, Ewald Friedrich von Hertzberg, to discuss with the French envoys how peace could be restored in the republic. In this way he could assert himself against his sister for the stabilization in the republic.

Wilhelmine's reign

Before leaving for Berlin, Wilhelm V had entrusted his wife Wilhelmine of Prussia with his official duties. With the change of person, the interests of the republic should now become of greater political importance for Prussia than under Wilhelm. Whether Wilhelm V consciously factored in this fact is, however, controversial in research. What is certain, however, is that Wilhelmine's letters increased the pressure on Friedrich Wilhelm II. So she wrote on February 6, 1787 in Nijmegen that she preferred abdication to a compromise solution:

"If we cannot return to The Hague with honor, it is better that we withdraw completely."

In fact, however, the largely disempowered inheritance holder stood in front of the closed doors of The Hague . As the meeting place for the States General, the city was the center of political life. The refusal of Wilhelmine to attend the meeting further damaged her office. Only a message from Paris heralded a decisive change in the foreign policy framework.

Foreign policy paralysis of France

In the 1780s, the French kingdom was on the verge of bankruptcy. In particular, the financing of the American Revolutionary War had created a debt that the crown could only handle by taking out loans. To reorganize the state budget, the French King Louis XVI struggled . in February 1787 finally to convene the so-called Notable Assembly. Because of the strong public pressure, the French government assumed that the nobility and clergy would forego their privilege of tax exemption - a misjudgment. The failure of the French tax reform also affected France's allies in the Netherlands, where the Patriots also got into financial difficulties.

Prussian-French negotiations

Despite the obvious weakness of France, Frederick William II stuck to his mediating role. The king followed the advice given by his minister Karl Wilhelm von Finckenstein and his uncle Heinrich von Prussia . Only the war minister Ewald Friedrich von Hertzberg recommended the monarch to intervene. Hertzberg informed Wilhelmine in a letter that the Prussian king recommended that she renounce the rights of the inheritance holder's office. This compromise could then help her to continue in office. In order to achieve this goal, so the strategy of Friedrich Wilhelm II., Negotiations with each individual province of the republic would take place under joint French and Prussian mediation. However, in May 1787, the province of Holland refused to allow Franco-Prussian mediation. The previous concept of the Prussian government had thus failed for the time being.

Coup preparations

Since the French kingdom could not deliver weapons to the patriots due to its financial situation, the supporters of Wilhelm V prepared a coup d'état. For this purpose Wilhelmine asked the Prussian king, albeit unsuccessfully, to borrow military equipment from the Wesel fortress . Friedrich Wilhelm II still declared this impracticable out of consideration for France. In order to still provoke a major pro- Iranian uprising in The Hague, pamphlets and newspapers announced in June 1787 that William V was returning with 10,000 soldiers to restore his position as inheritor. In truth, the number of soldiers reported was far fewer. There was also no further march by Wilhelm V on The Hague.

The way to Prussian intervention

Wilhelmine's trip and wait

In order to prevent the civil war, Wilhelmine von Prussia planned a move that should force the Prussian king to intervene militarily. On June 26, 1787 Wilhelmine wanted to travel provocatively from Nijmegen to The Hague . Troops should not secure the carriages. After two thirds of the journey, the wagons were noticed at a Dutch border crossing and stopped before the ferry across the River Leck . At Schonhoven the inmates were asked by a patriot volunteer corps not to turn back, but to wait. Friedrich Wilhelm II described this "arrest", which was not a real one, since the princess was only supposed to wait for the decision of the States General about her onward journey in order to be able to continue her journey. In truth, Wilhelmine was housed in the commandant's house and treated appropriately. Ultimately, the States General decided to return Wilhelmine to Nijmegen.

Reaction of the Prussian government

Due to the length of the journey of the express couriers, Friedrich Wilhelm II was probably informed of the process of Wilhelmine's arrest on June 30, 1787. This gave his government enough time to calculate the consequences of a change in foreign policy. For the first time, the military option was considered by Friedrich Wilhelm II and his government. Nevertheless, in the legal understanding of the time, armed intervention was regarded as the "ultima ratio" or the "ultimate means". The king had to be able to justify a military intervention in terms of legal philosophy. He did this by portraying the prevented travel and arrest of his sister as a defamation of the entire Hohenzollern dynasty. The inviolability of the royal family had thus been called into question and could justify a campaign if the province of Holland should refuse compensation. As early as July 3, 1787, the king had troops gather in the Prussian Duchy of Kleve , which was directly adjacent to the Dutch province of Geldern in the east. In order to prevent a war with France, however, Berlin first tested at the negotiating table how strong the alliance between Paris and The Hague actually was in the face of the military threat. Should France really lack the economic means to send troops to the Netherlands, the Prussian government could count on quick military success. Since the patriots of Friedrich Wilhelm II were not recognized as legitimate government, not even a declaration of war should have been pronounced.

Rapprochement between Prussia and Great Britain

The foreign policy framework shifted even further in favor of Prussia: After holding talks with the London government, the Prussian diplomat Girolamo Lucchesini wrote a letter on July 3, 1787, informing Friedrich Wilhelm II that England was ready to militarily oppose Prussia Support France. The British Foreign Secretary informed Lucchesini that King George III. of Great Britain and Ireland were in favor of the Prussian king seeking retribution. On July 8, 1787, at least 40 fully equipped warships left the British ports to cover a military operation by Prussia by sea. In addition, France should be distracted from the Prussian troop movements in Kleve. London explained to Versailles that it was merely a harmless "naval exercise".

Conflict over the claim for compensation

Prussia also embarked on a deception against France: Friedrich Wilhelm II pretended to want to continue negotiations with France. His goal is still a non-violent Prussian-French mediation in the Netherlands. In truth, however, Prussian diplomacy made unfulfillable claims for damages that should be a prerequisite for joint mediation. Although Louis XVI threatened . 10,000 to 12,000 soldiers gather in Givet , but no such preparations have been observed. Its continued financial hardship made it impossible for France to invade the Netherlands. But more and more mercenaries and engineers were smuggled from France to Friesland to prepare for an uprising there. It was France's aim, with a change in alliance offers and bitter threats, to keep Prussia busy until France had the means to support the patriots through a campaign. The French strategy was seen through at the Prussian court, which is why the courtly environment asked the Prussian king to be allowed to begin an invasion in September 1787. Since it had still not been formulated how the compensation should look like, the king asked his sister to tell him what she was asking. Wilhelmine demanded the removal of French backers from the Netherlands, the disempowerment and disarmament of the patriots, and the reinstatement of Wilhelm V as inheritance holder. In addition, with Prussian support, she wished to be able to exercise influence on the office of inheritance holder even after Wilhelm's return.

invasion

Beginning of the advance

In an ultimatum addressed to the province of Holland, Friedrich Wilhelm II demanded that Wilhelmine's demands be fulfilled by September 12, 1787. When Holland refused to give satisfaction, on September 13, 1787, Friedrich Wilhelm left a 20,000-strong Prussian army under the Duke of Braunschweig invade the Netherlands. The king himself did not take part in the campaign, but in connection with this, a translation of the ode "On the return of Augustus" appeared in the Berlin monthly magazine. This allusion was intended to express that Friedrich Wilhelm II alone deserved the glory of the military action, because like Augustus , who had left the fighting in what is now Spain to his general Agrippa , the military expedition took place on his orders. The soldiers and officers are only the tools that carry out the king's will. The Prussian army reached Nijmegen on September 14, 1787. 40 British warships secured the coast against a possible French attack, which did not materialize. Although Louis XVI. to Friedrich Wilhelm II. that France was about to mobilize 100,000 soldiers, but this was recognized as a bluff in Berlin. The further the Prussian soldiers advanced, the more the French court withdrew their support from the patriots. As a result, the resistance of the patriots largely collapsed.

Capture of Amsterdam

On October 1, 1787, the Prussian army was already at the gates of Amsterdam . Many of the leading patriots had fled to the important trading metropolis and the most populous city in the republic. The Prussian Field Marshal Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Braunschweig gave the city government until 6:00 p.m. to submit to Wilhelmine's demands and to allow the troops to enter. The Prussian War Minister Hertzberg also insisted in a letter that Amsterdam should be taken by the military:

In the Prussian camp there was a plan to bring Amsterdam down with an artillery bombardment, but fortunately this option was rejected by Field Marshal von Braunschweig. Instead, he launched nightly attacks on the city. Amsterdam held out until October 10, 1787. The city only surrendered when the news came from France that no more help was to be expected. For Louis XVI. the fall of Amsterdam meant a serious diplomatic defeat that irreparably damaged his reputation among the French public. Later Napoleon would see the "national disgrace" as a main reason for the outbreak of the French Revolution .

Persecution of the Patriots

The Prussian military expelled the leading figures of the patriots in the French Kingdom and the Austrian Netherlands , dissolved patriotic associations, disarmed voluntary corps and carried out a review of the political views of officials, which also resulted in brief arrests. Wilhelm V was able to return to The Hague and restore his power as inheritance holder and captain-general.

consequences

Prussian troops are stationed in the Netherlands

Although the Prussian government had at least managed to avert the open civil war in the Netherlands with rapid military intervention, the situation was still by no means over. Hertzberg in particular feared that after the planned withdrawal of the Prussian troops in November 1787, France could have seized the opportunity to intervene militarily on its part. In this case, all the successes he saw could have been reversed. A letter of appeal from Wilhelmine finally convinced Friedrich Wilhelm II to leave 4,000 soldiers in the province of Holland . The Duke of Brunswick, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand , gave another 3,000 of his own troops to the republic.

Prussian influence

Friedrich Wilhelm II had not achieved any territorial expansion of Prussia in the Netherlands. He also waived reparations payments from the city of Amsterdam , as Wilhelmine had warned him that it would adversely affect the "interests and fame of the king". The Prussians, she wrote, came as liberators. But if he were to claim reparation, he would be viewed differently. However, Friedrich Wilhelm II wanted to use his military influence to control the regent families and officials of the republic in his favor - which, however, was not crowned with success in the long term. It was even more important to Friedrich Wilhelm II to secure Prussia's position as a great power through an "alliance system of the north". Berlin envisaged an alliance between Prussia, Great Britain and the Netherlands, a diplomatic counterweight to France and Austria. In this way, the previously prevailing foreign policy isolation of Prussia was to be overcome. The first step for this alliance was an aid agreement between Prussia and the republic.

Alliance agreement

On April 15, 1788, the agreement was signed in The Hague . In the event of an attack, both powers undertook to support each other militarily. Prussia guaranteed the independence of its contractual partner. On the same day, Great Britain signed another aid agreement with the republic. On April 19, 1788 representatives of Prussia, Great Britain, the Assembly of States General and Holland signed an additional alliance. In it, the Kingdom of France was named as a common enemy and the sums that were still to be paid to Prussia for its military use and troop stationing were given. The maintenance of the now restored conservative system of government by the undersigned powers should also be ensured. The first article stipulated that Prussia had to make 66,000 soldiers available to the alliance. A military council of the three states should decide on their deployment. In addition, the Prussians should be able to be supported by British and Dutch troops in an emergency. The third article determined the payments to Prussia: Great Britain and the Republic were to pay £ 50,000 a month each. In accordance with Article 5, Friedrich Wilhelm II. Received an additional £ 1 and 12 Schilling per month from each ally for the provision of individual soldiers. With that the king got rid of a third of his entire army. The Prussian government even planned to expand the alliance network to include the Russian Empire, Sweden and Denmark. With such powerful allies, Friedrich Wilhelm II believed that he could permanently secure the state of peace in Europe - a hope that a few years later would prove to be an illusion.

Collapse of the alliance in the course of the French Revolution

In 1788, the three acting states could not foresee that neither their treaties nor their plans with each other would last. After the invasion of troops of the revolutionary French Republic in the First Coalition War (1792-1797), the Republic of the Seven United Provinces ceased to exist as early as 1795, and with it the inheritance. It was replaced by the Batavian Republic , which was dependent on France, and, from 1806, the Kingdom of Holland . Prussia, militarily abandoned by Great Britain, declared neutrality towards France in the Treaty of Basel .

literature

- David E. Barclay: Friedrich Wilhelm II. (1786–1797). In: Frank-Lothar Kroll (Ed.): Prussia's rulers. From the first Hohenzollern to Wilhelm II. (= Beck'sche series. 1683). Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54129-1 , p. 190.

- Curt Jany : History of the Prussian Army from the 15th Century to 1914 . Ed .: Eberhard Jany. tape 3 . Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1967, p. 209–216 (extended edition of the original edition from 1928).

- Friedrich Wilhelm von Kleist : Diary of the Prussian campaign in Holland. 1787. (digitized version)

- Theodor von Troschke , The Prussian Campaign in Holland 1787 , 1875, (digitized version)

- Theodor Philipp von Pfau , History of the Prussian Campaign in the Province of Holland , 1790, (digitized version)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The policy of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 1st edition. 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 18th ff .

- ↑ a b c d e Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 20th ff .

- ↑ a b c d Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 24 ff .

- ↑ a b Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The policy of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 31 ff .

- ↑ a b c d Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 35 ff .

- ↑ Pericles in Prussia: The Politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the Mirror of the Brandenburg Gate, p. 35 ff.

- ^ A b Hans Ulrich Thamer: The French Revolution . 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-50847-9 , pp. 23 .

- ↑ Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia. The policy of Frederick William II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 36 .

- ^ A b Brigitte Meier: Friedrich Wilhelm II. King of Prussia: A Life Between Rococo and Revolution . 2007, ISBN 978-3-7917-2083-8 , pp. 113 .

- ↑ a b c d e Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 45 ff .

- ↑ Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia. The policy of Frederick William II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . S. 71 .

- ↑ a b c Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The policy of Friedrich Wilhelm II. In the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . 2014, ISBN 978-3-7375-0749-3 , pp. 80 ff .

- ↑ a b c Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The policy of Friedrich Wilhelm II. In the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . S. 98 ff .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate . S. 119 ff .

- ↑ Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The Politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II in the Mirror of the Brandenburg Gate, p. 122 ff.

- ↑ a b Zitha Pöthe: Pericles in Prussia: The Politics of Friedrich Wilhelm II. In the Mirror of the Brandenburg Gate, p. 122 ff.

- ↑ a b Zitha Pöthe: The policy of Frederick William II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate. . S. 134 .

- ↑ a b Zitha Pöthe: The policy of Frederick William II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate. . S. 142 ff .

- ↑ a b Zitha Pöthe: The policy of Frederick William II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate. . S. 149 ff .

- ↑ Zitha Pöthe: The policy of Frederick William II in the mirror of the Brandenburg Gate. . S. 150 .