Old Prussian Army Organization

The old Prussian army organization treated the structural organization of the Prussian army from its beginning as a standing army from 1644 until its total annihilation as a result of the devastating Prussian defeat in the war against France in 1806/7.

The army reformed between 1807 and 1814 (New Prussian Army) differed fundamentally in their army organization.

Organization of the old Prussian army

Like all armies in the period from 1644 to 1806, the army consisted of the arms of infantry and cavalry . Artillery was added later as an independent branch of service . The Prussian army focused more on the infantry. In the view of the commanders at the time, the two branches of arms cavalry and artillery represented little more than support forces for the infantry. This is expressed, for example, in the infantry-based training of artillery or dragoons . As the increase in the numerical size of the army over the course of time suggests, the number of newly established military units rose in parallel. In all three branches of service, the regiment was the largest form of organization in the army. The strength changed over the course of time, so that uniform figures are not possible.

- The infantry trained 60 infantry regiments by 1806.

- The cavalry consisted of 35 regiments in 1806 .

- The artillery consisted of 4 field artillery regiments and 14 fortress companies in 1806 .

In addition to these three branches of service there were:

- Garrison troops

- technical troops (for example miners and the engineers )

- Minstrels

- the medical service (which hardly deserved its name at the time)

- the field preachers

infantry

The organizational units of the Prussian infantry were in order of size: 1st regiment , 2nd battalion , 3rd company , 4th platoon .

The development of the organizational structure of the Prussian army took place in a long process. Until around 1680, the individual infantry regiments had very different sizes. It was not until the 1680s that a fixed organizational form emerged in the regiments. This development was caused by the fixed financing and planning of the funds by the elector, which made fixed numerical reference values necessary.

The first organizational standardization of the Prussian infantry was ordered in the regulations on May 17, 1713 and February 28, 1714. In it the strength of an infantry regiment was set at 1,390 men. An infantry regiment consisted of two battalions and ten companies . At the time, a musketeer regiment consisted of 40 senior officers, 110 non-commissioned officers, 30 tambours (drummers), 130 grenadiers and 1,080 musketeers.

This regulation remained in effect until 1735 and 1743 respectively. From then on, two additional grenadier companies were formed within one regiment. So the strength of an infantry regiment increased to 1,597 men.

Until the collapse of the old Prussian army, a total of 60 infantry regiments were formed.

Grenadiers, musketeers and fusiliers were the main types of infantry in the Prussian army in the 18th century.

Musketeers

The musketeers were the line infantry of the Prussian army. They were named after their weapon, the musket . After the invention of the flintlock shotgun , the musket became obsolete, and from 1680 only flintlock shotguns were used. Unlike in other European countries, however, the Prussian musketeer regiments retained their name as an honorary title, even if they used the new flintlock shotgun. The 1st to 31st Infantry Regiments (with the exception of Infantry Regiment No. 6 ) were musketeer regiments.

Grenadiers

The task of the grenadiers was to throw 1.5 kg grenades (French: grenades ) at the enemy infantry in order to give the musketeers time to load their weapons. They were used on the wings. With the improvement of the weapons (flintlock shotgun) the grenades became superfluous. Although they were robbed of their original function, due to their exposed position in battle (flanks) and their physical superiority, they were considered an elite unit in the Prussian army. Their numerical share was 17 to 18 percent in the Silesian Wars . There were two grenadier companies in each musketeer regiment. In addition, the Infantry Regiment No. 6 the designation Bataillon Grenadier-Garde.

Fusiliers

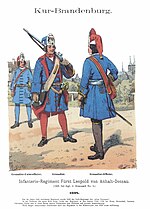

From 1723 fusilier regiments were also established. The fusiliers were equipped with a slightly modified shotgun. The shotgun should become lighter overall. In practice, the Prussian standard shotgun was shortened by about a hand's breadth. So the newly formed fusilier regiments were formed mainly from smaller soldiers. Otherwise they had the same function as the musketeers, and the fusilier regiments also had the same structure as the musketeer regiments. Outwardly, the fusiliers differed in their headgear. Musketeers wore a three-cornered hat while the fusiliers wore a high headgear resembling a grenadier's hat. Initially, the fusiliers were viewed as secondary. At the beginning of the Seven Years' War, for example, they were only given back seats. The infantry regiments No. 32 to 60 were designated as fusilier regiments, even if their function did not differ from the musketeer regiments.

After the army reform, fusiliers made up new elite units of the Prussian army. Since they were also trained for rifle combat and were less intended for line combat, they were the only infantry units that were able to assert themselves against the French troops with their tirailleur tactics in 1806.

Free battalions / light infantry

During the Silesian Wars, Frederick II recognized a lack of light troops for the small war, which was becoming more and more important . The formation of hussars alone could not remedy this deficiency; so he commissioned the formation of free infantry units and free corps (from different branches of service). A total of 14 free infantry units and 6 free corps of different sizes were set up, which mostly showed poor performance in combat. They were affected by a high rate of desertion . The reason for this is that the units consisted mainly of Austrian, French and Hungarian prisoners of war . After the Seven Years' War these units were disbanded, but were also formed at short notice for the last cabinet war, the War of the Bavarian Succession .

cavalry

The organizational units of the cavalry were in order of size: 1st regiment , 2nd squadron (French) squadron , 3rd company, 4th platoon.

In 1656 the cavalry still made up 54 percent of the army. After the introduction of the flintlock rifle and the bayonet , however, the cavalry increasingly lost its importance in the Prussian army. At the beginning of the 18th century, their share in the army fell to 20 percent.

Similar to the infantry, there was initially no uniform form of organization, armament or clothing in the cavalry. The regulations that were introduced under Friedrich-Wilhelm were of essential importance. Mention should be made of the catering order introduced in 1718 , the billing regulations and the drill regulations of March 1, 1720, which regulated the armament, uniforms, accommodation and organization. From then on a cavalry regiment consisted of 728 men and 742 service horses. It included 5 squadrons and 10 companies. This did not apply to the dragoon regiments whose strength fluctuated considerably. Under Friedrich-Wilhelm I, the cavalry suffered from the overemphasis on infantry tactics. The horse was seen less and less as a means of attack, but more as a fast means of transport for mounted infantry.

In 1740, when Friedrich II took office , the cavalry consisted of 22,344 men with 19,801 horses. Due to his regulations of 1743, the numerical number of regiments changed again. A cuirassier regiment now numbered 833 horsemen, a dragoon regiment 847 soldiers and a hussar regiment 1,172 men. When the cavalry was brought to peace strength in 1763, it consisted of 32,930 cavalrymen. Including 10,859 cuirassiers (33 percent), 11,990 dragoons (36 percent), 9,740 hussars (30 percent). By 1786 a total of 35 cavalry regiments of various types of cavalry had been formed.

After 1786 the artificial difference between cuirassiers and dragoons was eliminated. Both types now represented the battle cavalry. A cuirassier / dragoon regiment now consisted of 783 men. In 1806 the cavalry was still regarded as the best Prussian armed force, despite its lower striking power than it used to be.

In the Prussian cavalry, the cavalry types were the cuirassiers, the dragoons and the hussars.

Cuirassiers

The cuirassiers got their name from the iron breastplate weighing up to 12 kg - the cuirass . Their armament consisted of a carbine , two pistols on the saddle and a saber . The cuirassiers were the heaviest and most distinguished class of mounted troops and represented the actual battle cavalry in the Prussian army. This is also evident from the fact that regiments newly established after 1691 enriched themselves with experienced and experienced dragoon regiments, which promoted the elite status.

The term cuirassier regiments did not come into use until 1742. Before that, the cuirassier regiments were called regiments on horseback. 13 cuirassier regiments were established by 1786.

dragoon

The Dragoons were designed as mounted infantry, so the training of the Dragoons was strongly adapted to the infantry regulations. Originally they were supposed to reach their place of work on horseback but fight on foot. Foot exercise and firefight were more important to the Dragoons than horseback riding. Friedrich-Wilhelm I ordered the dragoons to do infantry every third day. At the time of Frederick the Great, the dragoons were basically the same armament as the cuirassiers, but they did not wear the typical cuirassier breastplate. They were used just like the cuirassiers and after 1786 the barely existing differences between the two types were eliminated.

By 1786 there were 12 regiments of dragoons.

Hussars

The hussars were first set up in 1721 due to the experience gained in the War of the Spanish Succession . Hussars represented the light cavalry of the Prussian cavalry. They were originally intended for shock troops and small wars. Their use lay particularly in the rapid and extensive reconnaissance and in raid-like actions on the enemy's supplies. Typical of the Prussian hussars were their fur hats and their curved sabers. By 1786 there were 10 hussar regiments, each with 10 squadrons .

artillery

- See also: List of old Prussian artillery regiments

The artillery in the Prussian army was distinguished between field artillery and garrison artillery. By 1806 a total of four field artillery regiments and 14 fortress artillery companies were established. The field artillery was organized according to size: 1st regiment, 2nd battalion, 3rd company.

It took a long time for the artillery to be integrated into the Prussian army as an independent branch of the army. This was caused by the fact that this weapon originally had an urban bourgeois character. Artillerymen did not see themselves superficially as a military force, but rather as a bourgeois guild. The artillerymen were superficially anxious to protect their knowledge from outsiders.

An important step in making artillery a branch of arms was to standardize the training of artillerymen and concentrate them in Berlin. This applied from 1687. This step was also necessary due to the expansion of the fortresses in Brandenburg-Prussia and the associated higher demand for artillery. In 1697 the artillery was separated from the organizational connection to the fortresses and a first artillery corps was formed. In 1700 this consisted of 409 men and 10 companies.

The problem with artillery has long been its field utility. The weight of a cannon was considerable, so carrying cannons made an army slower and more immobile. If defeat in open battle threatened, this usually meant the loss of all cannons. During the War of the Spanish Succession , artillery was viewed as extremely disparaging by the commanders of the Prussian army. The Prussian corps under the leadership of Prince Leopold von Anhalt-Dessau was not given any cannons at all.

A rethink took place under I. Friedrich Wilhelm instead. In 1716 he formed the artillery corps into a field battalion consisting of 5 companies and 4 fortress companies. The garrison of the field battalion was Berlin . The 4 fortress companies were stationed in Magdeburg , Wesel , Pillau and Stettin . The artillery corps now numbered 805 men and the division between field and fortress artillery began to be prepared.

| 1688 | 1712 | 1722 | 1740 | 1786 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1430 | 2003 | 2510 | 2741 | 5041 |

The training of the artillerymen was strongly influenced by the infantry. It was more important to drill than to control the cannon .

Under Frederick the Great there was a further breakdown of the artillery. Each infantry battalion was assigned two small-caliber cannons as light artillery (4 cannons per regiment). Half of these guns were operated by untrained musketeers.

In 1786, the year Frederick the Great died, the proportion of artillery in the Prussian army had risen to 5.5 percent.

Despite a quantitative superiority of the Prussian army, the Prussian artillery proved to be inferior to the French artillery in 1806. The reasons are deficiencies in the organization and the material (the cannons were too heavy and too poorly drawn).

1. Field artillery

In 1656 the field artillery of the Brandenburg Army consisted of 48 cannons and howitzers of various calibres. In 1716 the field artillery consisted of a field battalion of 5 companies. From 1731 the strength of the field artillery was 785 men through the establishment of a 6th company. Already in the first Silesian Wars it became obvious how inadequate the strength of the field artillery was. In 1741 a second field artillery battalion was established. It consisted of five companies and had a crew of 566 men. In 1744 the first field artillery regiment emerged from the first and second field artillery battalions. In 1756 the regiment had increased to 1709 men and was equipped with 360 field guns.

| 1656 | 1744 | 1756 | 1758 | 1759 | 1760 | 1761 | 1762 | 1763 | 1768 | 1786 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | 222 | 360 | 393 | 536 | 523 | 532 | 662 | 732 | 874 | 930 |

The Seven Years War forced Frederick the Great to enlarge the artillery. Success on the battlefield was no longer possible without artillery preparation. The number of artillery pieces doubled between 1756 and 1763. After the end of the war, the second and third artillery field regiments, each with 2 battalions, were established.

In 1763 the artillery had a head count of 6,309 men. In 1772 the fourth field artillery regiment was formed, which consisted of 2360 soldiers.

2. Fortress artillery

In 1716 four garrison artillery comings were formed. In 1731 the strength of the garrison artillery was 423 men. To secure the conquered Silesian province, Frederick II formed a new artillery garrison company in 1742. The Silesian Artillery Corps was formed from it in 1753. In 1756 the number of garrison artillery companies had increased to eight. In 1763 there were 453 men in the old garrison companies and 693 men in the Silesian artillery corps. In 1786 there were a total of 14 garrison companies.

garrison

In the early days of the standing armies, the field troops formed the garrison. In the event of war, often only a remnant of soldiers remained who were supposed to defend the fortified places. From 1717 Prussia started to form regiments through garrisons . The reason for this lay in the supply of disabled soldiers and officers from whose ranks the regiments were composed. The garrison regiments were viewed as second class from the start. In 1726 the garrison units already numbered 7,000 men.

There were three fortress bars that were supposed to protect Prussian territory.

The important fortresses under Friedrich-Wilhelm I were the towns of Berlin, Küstrin , Spandau , which covered the Prussian heartland , and from 1720 in particular Magdeburg , which was expanded to become the main fortress of the kingdom. These represented the first fortress bar.

The fortresses in the western areas cut off from the heartland, which formed the second fortress bar, were of particular importance. These were Geldern , Hamm , Minden , Lippstadt and Wesel, which was expanded to become the main Prussian fortress in the west.

The third fortress bar were the fortresses of Pillau , Memel , Kolberg and Königsberg protecting the East Prussian territory .

Due to the tense military situation in the Seven Years' War, Frederick the Great used the garrison regiments for field service. There the regiments could hardly fulfill their tasks. In 1776 there were 21,690 garrison troops in the Prussian army in 36 garrison battalions. It was customary to replenish the garrison regiments with old or disgraced officers and physically weak soldiers. This retaliated in 1806 when most of the Prussian fortresses surrendered to the French troops without a fight, despite the magazine being full.

literature

- Hans Bleckwenn : Under the Prussian eagle. The Brandenburg-Prussian Army 1640–1807 . Bertelsmann, 1978; ISBN 3-570-00522-4 .

- Hans Bleckwenn: The Frederician uniforms: 1753–1786 ; Dortmund: Harenberg 1984 (= The bibliophile pocket books No. 444); License d. Biblio publ. Osnabrück as: The Old Prussian Army; Part 3, Vol. 3, 4 and 5; ISBN 3-88379-444-9 .

- Jörg Muth: Escape from everyday military life , Rombach Verlag, Freiburg i.Br. 2003, ISBN 3-7930-9338-7

- Olaf Groehler : The army in Brandenburg and Prussia from 1640 to 1806 - The army , 1st edition, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-89488-013-9

- Martin Guddat : Cuirassiers Dragoons Hussars The cavalry of Frederick the Great , Mittler & Sohn publishing house, Bonn 1989, ISBN 3-8132-0324-7

- Gerhard Ritter: The old Prussian tradition (1740–1890) . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 1970, ISBN 978-3-486-45744-5 z. T. online at google books

- Kurd Wolfgang von Schöning : Historical-biographical news on the history of the Brandenburg-Prussian artillery . Volume 1, Berlin 1844 ( full text )