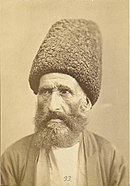

fur cap

A fur hat is a winter headgear made of fur ( hat = southern German and Austrian partly hood , also cap ). According to the usage in textile headgear with a skin cap edge is referred to as fur respectively.

In the classic women's and men's fur hats, a distinction is made between the simple shape and those with a split double edge, in which the rear edge can be pulled over the ears. Also hats with a peak, the so-called hunting or Hubertus hats, have meanwhile found their way into general fashion.

The craftsmen of the milliners and furriers are mainly concerned with the commercial production of fur headgear .

General

Fur headgear differ in shape and the type of fur from which they are made. Both can be influenced or determined by the intended use, costume (regional, job-related) or, especially in recent times, by fashion. The local availability of the fur material is particularly important for the historical hat. The fur hat and the fur hat are reserved for the colder areas, in summer and in areas without winter fur appears only occasionally as a headdress, especially in historical clothing as a trophy for local hunters, without a warming purpose. Especially after 1945, the end of the Second World War , fur hats and caps were an important part of German hat fashion and the fur fashion that was particularly flourishing at the time for a few decades.

Work technique

Soft, not stiffened fur hats are cut according to a pattern (technical term: matching). Usually the fur is stretched after opening , removing any damaged areas , in order to smooth it out and to make optimal use of the fur surface. The matched parts of the hat are joined together with a fur sewing machine or an overly hand seam and the seams are then smoothed. As a rule, they are lined with fabric, possibly also padded. Except for hood-like shapes that lie flat on the head, they are provided with a hat band corresponding to the respective head size for better hold and as protection against stretching.

For fixed models, the skins are attached to the block (cap block, cap block, cap stick) and then cut into shape. After sewing, they are damp, with the hair facing outwards, pulled over the block and tied in place with pins and pliers or a hand, electric or compressed air tacker . Individual details (folds, imitation ear flaps, etc.) are formed with cardboard strips. For particularly high-quality processing, an adhesive gauze can be used at the same time, which after drying results in a particularly soft and light cap. Instead of the previously regularly used stiff tulle or stiff gauze that sticks when wet, a lattice-shaped plastic mesh is usually used as the base material today.

history

Furs with their heads left on and fur heads were already part of the mythical headgear and headdress of hunters and warriors in many countries. The “magician” of the cave paintings of Trois Frères in Ariège wears bison skin with a headboard, used as a mask and hat. The juxtaposition of hunter's camouflage and cultic fur clothing has persisted for thousands of years. Germanic warriors occasionally wore a wolf mask with a wolf's tail, Egyptian priests, at least in cult, a dog mask. Assyrian dancers sometimes used lion masks to mask themselves during the war dance. Old Cretan priestesses wore young leopards as headdresses, one Cretan priestess even adorned her hat with a stuffed young leopard. In India, the Mitanni adopted masks made from peacock skins. For example, fur masks with non-ritual use show hunting masks on Egyptian pallets from the early days. In Central America, for the Mixtecs and Mayans and in South America for the tribes on the Paracas Peninsula, masks or hats made of jaguar skin were part of the cult and war costumes.

Fur hats are one of the oldest headgear, at least in cold areas. Headgear that is believed to have been made from otter skins was found in the remains of stilt houses. A fur hat completely encrusted with salt was found in the Hallstatt salt mine , dating from around 2000 BC. BC, so the Bronze Age. In the Middle Ages and modern times, headgear made of fur was an eye-catching status symbol if it was made from exclusive furs such as sable .

Around 700 BC The Greek poet Hesiod suggested for the winter: "For the feet sandals made of ox skin , around the chest a cape made of kidskin and on the head a flat fur hat that also protects the ears."

Even today, in the cold parts of Asia - Mongolia, for example - almost every inhabitant has a fur hat. It is often made from materials that pastoralists already have, such as lambskin or goatskin .

Simple hats made of lambskin or sheepskin were often made in rural areas by the shepherds and farmers themselves. However, since the furriers had the possibility of a more professional tanning of the skins, these are likely to have taken over the production there in the course of time. With the modern fur fashion, around after 1860, the fur caps and hat shapes became more refined, they now often required special wooden shapes for production, depending on the fashion in constantly new models. This made production mostly unprofitable for the individual furrier. With the few pieces of a model that he sold, it could happen that the wooden block, which was laboriously manufactured, cost more than the benefit of the fur caps made on it. This created the basis for fur hat specialty companies that supply furriers, hat and textile shops and department stores, but also haute couture .

In Central Europe, winter headgear was often lined or trimmed with fur. Hartmann von Aue writes in his Iwein around the year 1200 that old people should wear hats made of fox fur in winter. In the second half of the 13th century, the cap, which was only slightly bulged in the Middle Ages and often had cross stirrups and a button in the middle, developed into a high brim, which was often made of fur, or ermine for noble men. The so-called peacock hat, which was mainly worn by higher ranks for hunting, often had a fur-trimmed brim.

The caps and hats with fur edges were taken from the high medieval costume and developed further. The farmer also wore a narrow-brimmed hat made of fox fur or sheepskin. As far as can be seen in the old pictures - similar, roughened felt hats were current at the time - narrow or wide-brimmed fur hats can be found in fifteenth-century fashion - not so much in the second half.

Fur hats were retained in the 16th century. More modest than before, they reflected the rest of the clothing in the change in fashion. The hats flattened, the brim either ran all the way around or was turned up forwards or backwards. The beret, the essential headdress of the 16th century, often also had a fur brim that usually fell into two halves. Fur hats were worn equally by both sexes, local deviations were hardly noticeable. The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote about Lindau : All over the area, women wear fur hats or caps, which we also have here. The outer side made of appropriate fur, such as gray work , the inner side made of lambskin. Such a hat cost no more than three small silver coins. The openings that our hats have in the front are worn on the back so that you can see their frizzy hair . In the middle of the 16th century, the hat shapes also showed the transition to the rest of Spanish fashion, for example as a fur hat similar to the high Spanish hat.

In 1640, which was still during the Thirty Years' War , the Council of Leipzig the then felt obliged according Standes- and dress codes to craft and trade women to ban the wearing of precious sable and ermine caps.

The fur-lined housecoat, a garment that lasted until the advent of modern heating systems, often included a fur-lined or fur-trimmed hat.

While fur remained in traditional hats and bonnets, including conservative urban costumes, it was rarely used in fashionable headgear of the 18th century. Instead, fabric hoods or broad-brimmed hats, lavishly garnished with feather or floral decorations, sat enthroned on the towering hairstyles. Only occasionally was some fine fur used as a headdress, such as ermine. It was not until the turn of 1900 that headgear was trimmed like a coat more frequently.

Around this time, the number of types of fur used began to expand, and the possibilities for fur finishing , such as dyeing and later scissors, also increased. Krünitz (* 1728; † 1796) describes classic and new uses of fur : Zobel : The precious and expensive fur of this small animal is mainly used to decorate the hats . Marten is used for man's smocks, hats and clothing, but must first be dyed chestnut brown or stained black . From Iltis or Illing it also makes Mannsmüffe and caps . Ermine : With this very beautiful and precious fur , apart from its other importance, one also feeds the skirts of women of class, as one makes sashes, mugs, caps and their trimmings out of them . The ermine tails had a very special value, which is why they were also imitated by the furriers, the black tail tips they made from Lombard lambskins . The mink ... are used to make rashes on women's furs and hats . The following are ideal for making hats : otters, marmot and seal skins , the latter only to cover bad hats . The furrier takes the raccoon's skins , called “scales”, for making hats and mugs . Lastly, he mentions the well-known domestic lamb and mutton skins, which make a good lining in gloves and hats , and the various foreign sheepskins . According to Krünitz, the list of skins used in the 18th century is far from over. He does not yet name the chinchilla , which only became known in the 18th century; chinchilla fur has been very popular since the early 19th century, especially for sleeves, scarves and hats. The rabbit in particular is conquering fur, hat and cap fashion as an inexpensive rabbit fur in many varieties and finishes.

In the 19th century, fur was abundantly available as a trimming of headgear, pure fur hats were not entirely absent, but no fur hat or cap fashion was developed. Often the fur edges consisted of the same fur as the trimmings of the rest of the fur, or they matched the trimmings that were widely worn until the next century, consisting of a muff, scarf or collar and the fur or fur-trimmed cap. In winter, for example, a strip of fur often surrounds the capot and boot hats of the early 19th century and the crinoline era , while the wide-brimmed hat of the 1920s is almost exclusively decorated with ribbons , flowers or feathers . The still popular sporty hat, usually called a beret, is often worn in different versions made of fur or trimmed with fur. At the end of the 19th century, all hat shapes were also offered in fur, regardless of whether they were suitable for it or not.

In 1856 the H. Wolff company in Berlin began with the industrial production of men's hats, also made of fur, which were gradually sold by furrier shops. Around 1910 fur hats and caps also came into fashion in women's clothing. There were other special fur hat manufacturing companies, “they not only made the brisk Russian hats, but also created extensive collections. Wooden rams made it possible to model any shape out of fur - one was no longer bound to the round - fashionable, charming structures were introduced and joined Socks (from Feh and Ziegen ), decorated with herons and ribbons, agraffes and silk ”.

Towards the end of the 20th century, smaller furrier businesses in particular, whose main business was often the manufacture of hats, suffered from the emergence of hat fashion, which "had completely replaced this type of headgear". Then came the “smart” fur hat that was demanded everywhere. This in turn led to a real boost in the fur industry, which had remained in the same fashion for decades: "Not only the furrier had the most beautiful and easily sellable article for his shop window, department store and fur shops led the fur hat, the only fault of which was its durability" . At times the producers couldn't deliver enough because the fur hat was so popular. The first models were made of the black colored and sheared Selkanin , soon other short-haired types of fur were added. In 1932 the fur hat went out of fashion "and you rarely saw it in Berlin": "Why women suddenly turned down the dressy piece of fur, stopped buying it, has remained a secret of the capricious woman in fashion".

In the war year 1941, the fur hat came back into fashion. Due to the shortage of materials, the milliners had begun " to shape a small, turban-like structure out of the silver fox tail that easily hugs the hairstyle". Then the same thing happened to the Rotfuchsschweifen and in the same year there were again flattering hats, the round shape of the head of Fehschweifen held with ribbons. The fashion of women's fur headgear continued until long after the Second World War. The use of fur tails was continued in the mink tail caps, matching the corresponding small mink tail collars. The gentlemen mainly wore the shape of a boat or a cap in the style of the ushanka , the Russian cap with flaps on the ears.

In the folk costume

- Fur hats of the Yakut women ( Völkerkundemuseum Leipzig )

Largely independent of the respective fashions, folk costumes led a life of their own until they were mostly supplanted by modern fashion. The use of fur was used as a warming necessity, in some cases fur costumes that were only partially dependent on the fashion costume emerged, for which models and parallels can mainly be found in the urban costumes of the past.

Far more important than in hat and cap fashion, fur was used in peasant headgear at that time. Hats and caps made of fur or with fur trimmings were represented almost everywhere. Even then, men's costumes were less varied, they were generally limited to a few, recurring forms. Mainly a round, smooth fur hat made of lamb, beaver, marten, otter, fox or hare fur was worn , which differed at most in size or in a clumsier or more elegant finish. In Eastern Europe there were cylindrical shapes, sometimes narrowing towards the top, sometimes narrowing towards the bottom, as well as the tapering, often slightly indented at the top of the Tatar tribes.

In Russia they found their way into urban clothing and fashion in general. The national and landscape differences were particularly evident in the fabric parts of the trimmed hats. The headboard and brim were either sewn together or the brim was made in two parts and loosely, so that they could be folded down as forehead or neck protection. Every class and every social class had their own forms of clothing in ancient Russia.

The following are some examples of men's winter hats in Russia: The Moscow wholesale merchant went with the high karakul hat that tapered towards the top ; it set the tone as a garment for wealthy wholesalers. The wealthy trader, the wholesaler, who felt more like a normal bourgeoisie, wore the karakul hat in the typical Russian visor shape. The farmer's cap, which, like his coat, was made of sheep's clothing, followed at a correspondingly valuable distance. The hat was large, warm and comfortable, and had earmuffs that could be folded down for the very cold. There was probably no typical workers' fur hat, most of the workers were farmers at the time, who earned something in the city. The hats of landowners and (mostly foreign) manufacturers looked very elegant. It was particularly tall and made of the best beaver fur , its lid was made of valuable black fur. The Russian coachmen, rulers and taxi drivers had to wear a prescribed, very dressy cap with their long blue coats. It consisted of a black fur edge and a square made of blue cloth enthroned over the cap (a little bit similar in construction to the American doctoral hats already worn at graduation ceremonies ). The wealth of the owner could usually be read from the value of the fur used for the hat. These costly hats were usually only worn by the ruling coachmen, who were also equipped with correspondingly expensive furs. The simple taxi driver used almost only black-dyed cat fur . The townspeople, who did not want to wear the peasants' hats, preferred shapes of the common simple design. Soldiers, unless they wore a special uniform hat, had hats made of gray sheepskin. They were not as tall as those of the wholesale merchants, but of a similar design. The officer's cap, on the other hand, was round and smooth, made of karakul skin. The hat of the Kazan Tatars had the usual cut of Mohammedan headgear. It usually had a fox fur edge , but was also made from other valuable types of fur. The upper, warmly lined part of the cap consisted of simple silver embroidery or real gold thread, depending on the rank and wealth of its owner. The hat of the Caucasians is high, wide and made of Karakul, it was also worn in summer. In general, wearing thick fur hats was very common in the south of Russia in summer. In Astrakhan you could see the men, especially the dock workers, in light white suits and heavy fur hats in 55 degrees Celsius. Here the fur protected both from the heat and the sun's rays.

In most German national costumes, up to Transylvania , there is a fur hat with a colored hat mirror made of red, green or blue cloth, often additionally decorated with tassels, braids or embroidery. There were also variations in Holland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The blue, four-lobed fur hat on the rag is striking, and there was also a fur-lined pointed hat. The fur-trimmed Polish hat was also square; until the 19th century, traditional costumes showed the typical four-lobed women's hat with a fur edge. Russian women wore fur-trimmed hats of different landscapes.

- Winter costume in Montafon (around 1880)

In the 17th century, Altenburg costume included a striking, large, round cap made of black or brown bearskin , which was held in place by a leather strap around the forehead. In the 18th century, it was replaced by the so-called Saumagen , an almost cylindrical sable cap with a small black leather lid, with a small black leather lid on the top, and two silk ribbons hanging down from the lid. The somewhat smaller Barthelchen had the ribbons hanging on the side and tied under the chin.

There were similar cylindrical fur hats in Bavaria and Tyrol (upper Lechtal , here with an embroidered cloth bottom). More widespread, based on the southern German imperial cities, was the large, spherical fur cap of the 17th and 18th centuries; it was used as a festival and church costume in the foothills of the Alps and the Alps. Probably the longest, until the 20th century, it stayed in the three traditional costume areas of Vorarlberg , in the Montafon ("Pelzkappo"), Bregenz Forest ("Bräma- oder Otterkappo") and the Kleine Walsertal ("Briemkappe"). It was made of otter skin , seal skin - or beaver skin .

The cheekbones lined with fur or trimmed with trimmings also had their models in urban fashion. It framed the forehead and cheeks and was tied with ribbons under the chin. Among other things, it remained alive in the bridal hood of the Upper Silesian village of Schönwald (today Bojków , part of Gleiwitz) until the 20th century. The married women of the bride's suite there put a hood made of red, green or brown silk with silk ribbons on top of their white caps.

With a few exceptions, it can be assumed that the rural population adhered to the statutes of the Middle Ages and the later dress codes, which reserved the wearing of valuable furs for the nobility and other high-ranking people. She preferred to use the skins of native domestic and herd animals, especially sheepskin, and native animals from the wild, such as rabbits, hares, foxes, squirrels, and occasionally otters, beavers and seals, and occasionally also the skins of the small species of marten .

Another Hungarian hat, besides the four-pointed and others, was the stiff, tall kalpak , while the more hat- like Kucsma , usually with a fur brim , was soft . The way in which the Hungarian man from rural areas pressed on his pointed, high lambskin hat, showed his origins.

As part of military uniforms

Even in the earliest human representations, in which warlike and civil clothing could hardly be distinguished, men can be found with headdresses made of fur. On Neolithic rock carvings in eastern Spain, the hunters wear fantastic headgear in the form of animal headpieces .

The so-called warrior vase from Mycenae dates from the Bronze Age . While the outgoing warriors are helmeted, the attacking warriors depicted on the reverse wear hemispherical headgear, which is interpreted as hedgehog skins.

In the Iliad, there is hardly any leader missing a fur coat or at least a fur hat to complete the clothing. Diomedes covers his head with a balaclava made of ox skin , Dolon with a marten hood and Odysseus' fur cap is set with boar teeth.

With the advent of armor made of leather and iron, fur disappears for the time being from the war costume, and with it the fur headgear. Only when the Hungarian overcoat found its way into uniform fashion with the European hussar regiments in the late 17th and 18th centuries did fur come back into military clothing as a fur lining and trimming . Even the representative headgear was now mostly made of fur. They were either bearskin hats with drooping wings or the stiff, tall kalpak with a feather trim. The changes and constant changes were very big here. Most recently, at the end of the 19th century, the hussar hat, made of seal or otter skin with an overhanging cloth pouch, caught on. At times, other regiments also adapted to the hussar outfit, for example in France in the late 18th century and in the first half of the 19th century that of mounted hunters who wore fur-trimmed hats. The dragoons there had pointed hats trimmed with fur (also the Spanish ones), after the introduction of the helmet the yellow helmet of the Guard Dragon Regiment was adorned with a little leopard skin trim.

In the Frederickian era (1740–1786) the Prussian Uhlans also wore a fur hat that was matched to the hussar hat. In the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) the Tschapka then prevailed. In general, with a few exceptions, fur is limited to the headgear of the uniforms of the Western and Central European armies. The high bearskin hats were of particular importance. They were a noticeable feature of most European armies, with the exception of Prussia and Russia, from the second half of the 18th century until well into the 19th century. At first the resemblance to the high, pointed grenadier cap made of cloth can be seen, in the 19th century they become as lush as can still be seen today in the English royal guard. There the high bearskin hat is part of the peace uniform of the guard regiments. A less tall black fur hat was in use by the Scottish highland regiments in the second half of the 19th century.

The sheepskin hats of the Russian army, which were also adopted in the same or very similar manner by other armies that equipped their troops based on the Russian model, could be classified in a further group. The flat lambskin hat only became common in the Russian army in the second half of the 19th century, for example among line infantry, dragoons and artillery. In the late empire she wore the entire generals for decades, except for the generals and the tsar's wing adjudicators, who used a white fur hat.

In many ways, towards the end of the 19th century, the Serbian and Bulgarian armies were clad based on the Russian model. The parade uniform included black or white lambskin hats, in Serbia for the generals, in Bulgaria for the princely bodyguard. Around the same time, the Turkish army introduced a high, initially black lamb hat with a cloth mirror for the cavalry and artillery, during the First World War and then in gray. In terms of its scope, it was roughly equivalent to the Turkish Fez . The Konfederatka of the regiments of Congress Poland was a four-lipped cloth cap with fur trimmings.

In the army of the young Soviet Union, the lamb hat was limited to the Cossack army, where it was part of the uniform developed from the national costume. As early as the 18th century, the Cossacks wore high, cylindrical hats made of gray lambskin with a colored cloth bag or high cloth hats with a fur brim. The shape and color changed again and again, but they were never replaced by the pure cloth cap.

Headgear named for its shape

Some of the regional, religious or military hat shapes have their own names. In addition to the ones listed here, there are other, possibly less common terms. Among other things, the fur beret was once so common that in Augsburg, for example, there were only beret makers who specialize in fur berets.

In 1958, Dorothee Backhaus addressed the diversity of fur headgear in her “Breviary of Furs”:

“ And the hats, those infinite variations of fur hats that flatter the face so lovingly! It shouldn't necessarily be the solid, factory-made black Persian pots. Not exactly structures that resemble the Horse Guards' bear hats. But all those lovely bonnets and berets, those southwest hats and Rembrandt caps made of ocelot, those mink heads or raised cannotiers made of Persians, these nutria Cossack hats or hoods made of lambskin, aren't they really lovely? The Munich fashion guru Schulze-Varell once brought a gorgeous, chic beret made from wild mink. And Jean Dessès was certainly not wrong when he decorated his showcases with beaver bonnets. "

Ushanka or Tschapka

The Ushanka ( Russian ушанка) is a headgear that is also suitable for extremely cold weather conditions. It was adapted to different needs in different versions. The designation Ushanka (from Russian "uschi" у́ши, ears) indicates the possibility of folding down the flaps sewn into the edge of the hat and turned upwards to protect the ears and neck and possibly also the forehead when it is very cold. The model for the ushanka was introduced to the Finnish military in the 1930s, but after 1941 it was adapted internationally and used as standard headgear by the Soviet armed forces for the winter beyond the former states of the Eastern Bloc . It is still very popular with private individuals, various professional groups and organizations today. In terms of external appearance, the ushanka has become the epitome of Russian headgear.

The term "Schapka" (Russian шaпкa), which is widespread in English-speaking countries as well as in Germany, simply means hat, so the word does not fully reflect the meaning. For the military headgear of the same name, see → Tschapka .

In Austria , especially in the military , the similar fur hat is also known in the vulgar language as bears' fur .

Fur boat

The uniform boat is a headgear from the Scottish military tradition, which has spread beyond its international military use to various professional groups and organizations and is still very popular today. In Scotland this type of hat is known as Glengarry bonnet or Glengarry . The name Schiffchen , coined in Germany, is derived from its boat-shaped shape.

Often made of Persian or seal skin , the shape found its way into winter hats for men after the Second World War. Most of the time, the Central European boat was made pulled over a block of wood and therefore not always as flat as the military model. External fur ear flaps were possibly only simulated by the wooden shape, instead there were ear flaps made of knit or wool that were folded inwards.

The Turkish head of state Kemal Ataturk often wore a Persian hat, sometimes in the shape of a boat. The Persian boat is particularly widespread in the countries of origin of the Karakul sheep. Leonid Brezhnev also appeared on official occasions with a boat made of strong Persian skin. The little boat from Karakullamm is particularly typical for Hamid Karzai , the President of Afghanistan, who obviously carries it with him on all visits abroad.

Kalpak, Kolpak, Kolpik, also Hussar hat, English also Busby

The Kalpak , also Calpac , Kolpak or Kolpag , (from Proto-Turkish * kalbuk "high headgear", Turkish kalpak "(fur) hat"; furthermore Kazakh and Kyrgyz kalpak or qalpaq , Yakutian xalpaq ) is a tall, sometimes pointed or truncated cone Cylindrical hat mainly made of fur and / or felt for men, which is worn from Central Asia via the Caucasus and Turkey to the Balkans. From the Kalpak the Kolpak developed , a military headgear of the light cavalry, especially the hussars , or the light artillery.

While the Russian-Caucasian " Cossack " or " Tatar hat ", the papacha , is mostly made of lambskin , the Kalpak can consist of various types of fur and / or felt and often also has parts made of leather and cloth . However, there is some conceptual overlap. The high headgear made of Persian fur , the most precious type of lambskin that was popular in the Ottoman Empire and subsequent Turkey , was consistently referred to as Kalpak; likewise the karakul sheepskin hats , which were worn by aristocrats and Orthodox clergy in Greece and the Balkans in the 19th century.

The forms of the kalpaks are just as varied. In winter, thicker, warmer ones are worn, in summer lighter ones, the brim or ear flaps of which can be folded up as sun protection. The front of the cuff is sometimes slit so that it forms two protruding points. In general, pointed, conical kalpaks predominate in Central Asia , while in Turkey high, frustoconical or cylindrical ones . Both shapes have in common that they can be folded flat when not being carried.

Papacha, Cossack hat

The Papacha , plural Papachi ( Russian and Ukrainian папа́ха = papácha ; Georgian ფაფახი pʰɑpʰɑxi = papachi - here singular, the Georgian plural is called papachni ; Azerbaijani papaq ; Turkmen papaha ; Chechen холхазан куй = Caucasian head- wise to this day) for men and boys, which is also traditional in some parts of Central Asia , the Middle East and among the Russian-Ukrainian Cossacks . It is also a well-known part of the male costume of the Turkmens , Karakalpaks , Crimean Tatars and Nogais in western parts of the Eurasian steppes. Usually it is made from lamb or sheepskin. The origin of the name is likely to be in Turkic languages such as Azerbaijani and Turkmen, where papaha and papaq simply mean "hat".

In the Imperial Russian and Soviet armies, the papacha was used as a representative winter headgear for marshals and generals as part of the uniform of the armed forces . The Russian Armed Forces kept them.

In Russia it is sometimes referred to as Kubanka (after the Kuban River ); in German sometimes imprecise as a Cossack hat or Caucasian hat .

Schtreimel

The Schtreimel ( Yiddish : שטרײַמל, pl. שטרײַמלעך schtreimlech ) is a Jewish headgear. Today the Schtreimel is mainly, but not exclusively, worn by married Hasidic Jews during religious festivals and celebrations. The Schtreimel consists of a piece of velvet with a wide fur edge, usually made of tails of Russian sable or so-called Canadian sable , but also of pine marten tails or tails of American gris fox skins .

Due to the Shoah , the Schtreimel tradition in Europe almost died out. Only in Hasidic communities such as B. London , Antwerp , Vienna or Zurich there are Schtreimel wearers. Schtreimel are currently made in Israel , New York City and Montréal .

Spodek, Spodik

The Spodek or Spodik is a high, flat-topped fur hat with a conical shape. In contrast to the Schtreimel, the Spodik, of which there are several variants, is elongated, large, slim and rather cylindrical.

The Spodik was worn by certain groups of the population (Jews, Cossacks) in southern Russia, Poland and Galicia . The word, which comes from Slavic languages, has flowed into Yiddish and is occasionally adopted from there in German translations. Married men of the Gerrer Hasidim wore it on the Sabbath and on the Jewish holidays, it is considered a feature of the Gerrer Hasidim. However, this type of fur hat was worn by all Hasidic groups in Poland before the Shoah .

Peaked cap

Since the 1980s, the peaked cap has become increasingly popular, especially among men .

Named for the type of fur

Bearskin hat

The bearskin hat is a headgear worn by units of various armed forces as part of the parade uniform , as well as the headgear of Tatar peoples.

Karakul hat, Persian hat

The Karakulmütze (QaraQul), also Astra Chan or Persianermütze called (Persian: قراقلی) is a headgear from the skin of the Karakullamms. The typical model of the karakul hat for men is the so-called boat. In this form you can find them among other prominent followers of the Islamic faith in Central and partly in South Asia.

From around the 1920s to the 1980s, especially in the period after the Second World War, Persians were a preferred material in fur fashion, in addition to jackets and coats for women's hats and caps.

Faux fur hat

The faux fur or faux fur hat is made of imitation fur, depending on the fashion, in all common shapes like the real fur hats. Faux fur hats, on the other hand, are rather rare.

More fur headgear

Fur hat and cap

- Fur hats and caps for a furrier (Düsseldorf 2011)

In contrast to hats, fur hats and the headgear known as caps in Germany are not made soft and foldable, but rather stretched over a shaping block, see the article hat maker . This allows very differentiated models to be created. The durability of the shape is guaranteed by a stiffening insert.

In the second half of the 20th century in particular, fur hats were in great demand. Often a fur coat or jacket was worn with a hat or cap made of the same material as the garment or its trim (for example Persian coat with mink collar and mink cuffs, plus a Persian or mink cap). This also applied to the fabric clothing, which very often had a fur collar and fur cuffs.

The manual execution of this special work is usually done by millers, often by family businesses specializing in fur.

Fur hood

Hoods are usually part of a jacket or coat, permanently attached or detachable, and rarely their own headgear. If they belong to an item of fur clothing, they are usually made of the same type of fur, often trimmed with a longer-haired fur. The fur-trimmed hood has had a great renaissance since the beginning of the 21st century, from simple parkas to exclusive designer jackets. In addition to faux fur, materials are mainly fox skins of all kinds, especially sea fox fur and red fox fur , raccoon fur and long-haired lambskin .

Fur headband

Headbands made of fur are only found sporadically in regional costumes, but also among hunters in tropical regions, there for example made of leopard fur . In modern clothing, they are more or less strongly represented in the various fashion epochs, in addition to the fashionable aspect as forehead and ear warmers.

Leopard and wild cat fur hood (Central Africa)

Headdress

Particularly in peoples with traditional hunting, fur is occasionally used as a mere headdress without any warming intention. However, this is particularly common among many tribes of North American Indians . An essential characteristic of the hairstyle are the men's braids, which are garnished with otter tails or otter skin and worn in front of the body. Birdskin hats were worn on the Québec - Labrador Peninsula , where Inuit and Innu ( Naskapi and Montagnais Indians) live together.

Master furrier August Dietzsch (* 1900; † 1993) from Leipzig recalled in 1987: “ When horse and trams were increasingly being developed as a means of transport, the hat pins of the highly fashionable, mostly oversized ladies' hats that were common at the time proved to be a health hazard for passengers. Therefore, one could read in these means of transport: 'People with unprotected hat pins are not transported'. And for this reason we made hat pin protectors from ermine heads. Some women wore ermine without actually being able to afford it. "

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Alexander Tuma: Pelzlexikon, XIX. Volume, XX. Band . Alexander Tuma publishing house, Vienna 1950, keywords “beret”, “cap”, “fur hat”.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: Fur and fur clothes of antiquity . In: The fur trade. Vol. XIX, New Series, 1968 No. 2, pp. 31-34.

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt: Fur in European clothes. Prehistoric time to the present. In: The fur trade. Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, booklets vol. VI / new series 1955 No. 2 to vol. IX / new series 1958 No. 6. --- 1955 booklet No. 2, p. 65, primary source: Fougerat , Pp. 255-256.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1955 No. 3, p. 96: V. 6535: sô should be protected with rûhen vuhs hüeten before the houbetvroste

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1955 No. 3, p. 96.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1955 No. 5, p. 166.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1956 No. 1, p. 24.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1956 No. 1, p. 19.

- ↑ Konrad Haumann: Costume-historical foray through the centuries. In: The tobacco market. Berlin, March 13, 1943.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1956 No. 6, pp. 237-238.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1956 No. 6, pp. 243-244.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1956 No. 6, p. 244.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1957 No. 3, p. 157.

- ^ A b c Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 2. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 23-25 ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

- ^ Jean Heinrich Heiderich: The Leipziger Kürschnergewerbe . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the high philosophical faculty of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität zu Heidelberg, Heidelberg 1897, p. 99.

- ↑ A. Popenzewa: Fur hats in ancient Russia. Men's hats. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 91, Leipzig, November 30, 1935, p. 3 (with 12 illustrations by Wladimir Falileef).

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, p. 40.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, p. 37. Kronbiegel: Primary source: About the customs of traditional dress and customs of the Altenburg farmers . Altenburg around 1806. Plate B. in s. 169, Fig. 2.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, pp. 37-38. Primary source Kronbiegel, plate B, Fig. 6 (Saumagen) u. 7 (Barthelchen).

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, p. 38.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, p. 38. Primary source Retzlaff-Helm: Deutsche Bauerntrachten . Berlin 1934, ill. P. 120.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, p. 39.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 1, p. 40. Primary source Höllriegl: Regi Magyar Rubák . Budapest 1938, fig. 15 a / b; 16 a / b; 19 a / b; 22 a / b.

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt: Men's furs in folk costumes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Vol. XVII 7 New Series, 1966, No. 3, p. 132.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, p. 270. Primary source Fougerat: Rock drawings from El Bosque in the province of Albacete. Pp. 54, 55, Fig. 29/30.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, p. 271. Primary sources Bossert: Alt Kreta. P. 78, Fig. 134/135, 1350–1200 BC BC - Fougerat p. 229,.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, p. 270. Primary source Fougerat, p. 44f.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, pp 274. primary source Martinet. Histoire du 9 e régiment de Dragons . Paris 1888, edition artistiques-militaires de Henry Thomas Hamel, plate 2.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, pp. 275-276. Primary sources: Accurate presentation of the entire Chur. Princely Saxon regiments . At the expense of the Raspische Handlung in Nuremberg 1769, pl. 17. - James Laver: British Military Uniforms . Pinguin Books, London 1948, plate 9 a. 11.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, p. 275. Primary source Richard Knötel, Herbert Knötel, Herbert Sieg: Farbiges Handbuch der Uniformkunde (? - only authors (Knötel / Sieg) indicated), Stuttgart 1994, p. 198, fig. 76.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, p. 275. Primary source Knötel / Sieg, p. 317f.

- ↑ Nienholdt, 1958 No. 6, p. 276. Primary source uniforms of the Polish revolutionary army. 18 aquatint engravings by Dietrich, Warsaw, 1831 Krakusen regiment and hunters on foot .

- ^ Dorothee Backhaus: Breviary of fur . Keysersche Verlagsbuchhandlung Heidelberg - Munich, 1958, p. 176 (→ table of contents) .

- ↑ Austria dictionary, de-at: Pelzmütze – Bärenfut. Retrieved May 30, 2009 .

- ↑ Directory: Soldier Language in the Wiktionary

- ↑ Wolf-Eberhard Trauer: The story of the Karakul sheep. In: Das Pelzgewerbe 1963/3, p. 183.

- ↑ Article Papacha in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BSE) , 3rd edition 1969–1978 (Russian)

- ↑ Andreas Vonach, Josef M. Oesch: Horizons of biblical texts: Festschrift for Josef M. Oesch for his 60th birthday , Saint-Paul, 2003, ISBN 3-525-53053-6 , p. 282. ( Preview in the Google book search )

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XXII. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1949. Keyword "Bärenmütze"

- ↑ Valeria Alia: Arts and Crafts in the Arctic. In: Wolfgang R. Weber: Canada north of the 60th parallel . Alouette Verlag, Oststeinbek 1991, ISBN 3-924324-06-9 , p. 102.

- ↑ Editor: A master furrier from Brühl remembers (III). In conversation with August Dietzsch. Brühl magazine ISSN 0007-2664 , January / February 1987, p. 29.