H. Wolff

| H. Wolff

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | one-man business |

| founding | 1850 |

| resolution | 1926 |

| Seat | Berlin |

| Branch | Fur clothing, fur wholesale, fur retail |

The H. Wolff company in Berlin was in its heyday, alongside the Paris company Revillon Frères , the largest company in the fur industry on the European continent, founded by Heimann Wolff (1830–1913) in 1850. About Victor Wolff (1858–1928) , the son of the company founder, it was said: "Kommerzienrat Victor Wolff is the pioneer of the Berlin fur clothing industry and the person who first introduced the concept of the organized, modernly managed large company into Berlin fur clothing and put it into practice". His workshop was considered "the high school of all furriers ".

Founding years

When the H. Wolff company was founded by Heimann Wolff in Greifenhagen ( Gryfino ) in Pomerania in 1850 , it was done in connection with a leather lacquer factory and the manufacture of hat visors. Most of Heimann Wolff's customers were furriers whom he visited as part of his business connections in Pomerania, West and East Prussia. It was obvious that the furriers also wanted to buy furs from him. So he began trading rabbit skins , initially on a modest scale and later on in larger quantities . Soon he relocated his gradually growing business to Berlin-Mitte at Chausseestrasse 67, albeit far outside, in front of the Oranienburger Tor . As a co-owner of Bambus & Co. , he also founded a hat factory in Berlin in 1856. As the first company to start manufacturing men's hats, they also started manufacturing fur hats , and sleeves and collars were made from rabbit fur .

Until the First World War

The company Bambus & Co. employed two travelers who visited the cities in the area. In addition to the cloth hats, they offered the furriers their made-up fur hats for men. At first the furriers, who were mostly hat makers themselves, refused to sell headgear that was not produced in their own workshop. The customers in Pomerania and Schleswig, where the first offers were made on a trial basis, were difficult to convince. Ultimately, the much cheaper price of the series products won, which promised higher sales and made greater use possible. Ultimately, the idea was so successful that more travelers could be hired, and customers soon found themselves abroad. Heimann Wolff now also had other fur products made. With the expansion of the railroad, his sales representatives regularly visited more and more distant areas. The model found imitators, and employees of the company became self-employed. In 1842 the company Freystadt & Co. had already tried to deliver fur items to their customers. Up to this point there was no industrial production of fur goods in Germany. Since 1878, the two Berlin companies AB Citroen and B. Brass have also been involved in the manufacture of fur clothing to a lesser extent (according to Emil Brass, even before H. Wolff). In addition to the traditional main place for the fur trade, the Leipziger Brühl , the center of German fur clothing was established in Berlin in the 1870s, together with the outerwear industry.

At the age of 17 Heimann Wolff's son Victor Wolff started an apprenticeship in his father's fur business. Here he acquired the basics of his later important specialist knowledge. Years of traveling followed, working in a number of similar companies. After returning to his parents' business, he redesigned the company, which was already highly regarded back then, "purposefully and energetically according to his plans", with his father giving him a free hand. In view of the currently blossoming women's clothing, the business premises were moved from the remote part of Chausseestrasse to significantly expanded business premises on Burgstrasse 28–29, also in Berlin-Mitte. At the same time, the hat business originally run by the father was dissolved, as the company developed more and more into a large company with made-up fur goods.

After Victor Wolff ran the company practically independently, he opened his own house in London in 1895, which was soon followed by a branch in Glasgow and one in Manchester. These proved to be extremely profitable, and so Victor Wolff went on to Paris to set up a branch in the Chaussée d'Antin, the finest business district at the time. This, in turn, was so successful that it soon had to be relocated to considerably larger rooms at 15 Rue Etienne Marcel, at the corner of Place des Victoires. The company also had a branch in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

In 1900, an agency and warehouse was established in Melbourne, Australia, which was soon followed by the same facility in Duma, New Zealand. New York City got a branch office and Canada got a business organization. Branches were set up in Petersburg and Moscow, and our own travelers traveled to Russia.

For the annual Leipzig tobacco goods fair on the second Saturday after Easter in the great hall of the Leipzig zoological garden, the main wall was reserved for the H. Wolff company, "which put up a splendid structure and let it cost something".

After Victor Wolff had been making the decisions in the company for many years, Senior Heimann Wolff finally left in 1904. At this point in time, Victor Wolff decided to have a new company building built, which should meet the requirements as a leading house in fur clothing.

During a ten-week Berlin furriers strike "to fight the job placement" in 1905, Victor Wolff's willing to work founded a so-called yellow organization . The main issue of the strike was the clarification of working hours on Saturdays, after employers had often returned to working hours of nine hours on Saturdays. The employers refused to appear before the unification office. Under the direction of Emil Brass , those willing to work published a small specialist journal. This organization, supported by the employers' association, fell asleep again because, according to the association of furrier journeyman, except for members of Victor Wolff, it had no access.

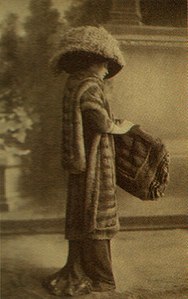

- Fur models by the company H. Wolff, collection 1910/1911

After the First World War

Since 1921, the company also had a branch at Leipziger Brühl. Its first manager was Hermann L. Schultze , who had been in New York for many years and worked there for his current company.

The great-granddaughter of the company founder visited the former Berlin business premises in Krausenstraße in 1991:

"The building still corresponded to the description of a brochure written in stilted English by my grandfather Victor from the 1920s," ... the elegant halls of our exhibition rooms on the ground floor of our house at Krausenstraße 17-18 ... The second floor of this building is for SMALL FURS and fur bearings. In these rooms, men who have acquired a worldwide education work in the art of selecting, evaluating and sorting of all kinds «.

It was not difficult to feel the vitality of the company in its heyday, when Victor still ruled here. He wrote about fur stoles made from sable , marten , mink or skunk and smaller collars made from mole , skunk, sable or mole-colored hamster .

- The elevator upstairs leads to the warehouses with wool and silk materials and the department for LADIES 'COATS and costumes ... Our way leads us on to the department for MEN'S COATS, where heavy winter coats, warm travel ulsters, raincoats, leather coats and jackets for driving and fur-lined coats for the day, the evening and sportswear can be seen.

The pelts and pelts used included raccoon , opossum , flying squirrel , white fox , gray fox , monkey , Persian , foal and marble .

" Fur hats, caps and leather hats were made in the rooms grouped around inner courtyards," exactly the same courtyards we found ourselves when we looked up out of the building as we wandered the corridors and crossed empty offices that have probably been around since the 1920s hadn't changed anything. And there, downstairs, were archways through which horse-drawn cars and later motor cars came in and out at the back on Schützenstrasse. "

Victor Wolff was described as a man who was still handsome in his old age, “who also knew this”. With the single lens in mind, he could be “enchantingly amiable”. “He chatted with an ease that was unparalleled, knew everything about the industry - knew the leading personalities in England and America and was always in control of the situation. Then he slowly got down to the business side, showed himself to be very well informed, and always managed to get a special advantage. The visitor was fascinated by his personality, and under such an impression he had to lay down his arms ”.

Philipp Manes, who was murdered in Auschwitz, wrote about the two sons that they were two completely different people from their father.

- Fritz Wolff (1891–1943), “very conscientious and hardworking, but not able to take his father's place”, was a friend of the arts and literature. He “wanted to play a role as a person who made people happy, and joined organizations on the left devoted his time and money to them ”.

- Herbert Wolff (1890–1974), "intelligent and highly educated, raving about all the arts, elegant, good speaker - but erratic and unsound in his character", was very similar to his father and therefore couldn't get along with him. In the business, there were “extremely unpleasant scenes that ended in complete separation”. In 1921 he married Nellie (born Danziger, 1898–1977), the daughter of the well-known lawyer Norbert Danziger . Herbert founded the company H. Wolff jr. In 1924 he took over the management of one of the leading tobacco shops in Leipzig, N. Händler & Sohn , Brühl 68. Already after a short time there, there were progress in improving internal and external organization. In 1929 Herbert founded Allgemeine Rauchwaren Handelsgesellschaft mbH. H. Wolff Junior , Krausenstrasse 17-18, which was "taken over" under the National Socialists in 1937 (quote from Manes). "He achieved great success for several years, and the name Wolff was once again listened to with respect". Herbert introduced the new Dutch Ejarrée rabbit fur in Germany, which earned him great merit. When the Dutch company collapsed, he too, the Berlin representative. He then succeeded in obtaining the representation of the important Hungarian lambskin finishing and trading company Pannonia . However, it was not enough to renovate Herbert Wolff.

The family also later remembered Herbert Wolff, much like Manes, as a “Playboy, a good-looking man who loved fast cars, elegant clothes, expensive boats and pretty women. He was charming but totally unreliable. ”However, while Manes writes that the rift between Herbert and his father was so great that Victor Wolff refused to see his grandchildren, in 2018 the family remembers the opposite. Dina Gold contradicts: “My mother, her brother and her sister remember their visits as children to Conradstrasse 1, Wannsee and that Lucie Wolff (born David, Victor's wife, 1868–1932) and Nellie (Herbert's wife and my grandmother) got on very well, he certainly never lost touch with his father. Nor did Victor refuse to see the grandchildren ”.

With the Royal Prussian Kommerzienrat Victor Wolff a serious ailment loomed and he decided to dissolve the company. In 1926 he wound up the company, paid generous severance payments to the employees and withdrew to his estate in Berlin-Wannsee. He didn't let anyone come to, "the crutches that he had to use when he was laboriously moving - they shouldn't be seen." Philipp Manes went on to write: "So this royal merchant died very lonely and almost forgotten".

The company H. Wolff jr. GmbH was liquidated in 1932. After the National Socialists came to power and the persecution of the Jews began, Herbert Wolff left Germany in 1933 and went to Palestine with his family. Divorced from his first wife in 1936, he remarried in 1940. His company had been taken over by H. Diamand and Robert J. Schäfer († 1922.). Their company still existed in 1941.

His brother, Fritz Wolff, was after a brief imprisonment in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and several arrests, was deported to Auschwitz in March 1943 and murdered there.

Personal details

Johanna Wolff (1838–1918) was the wife of the company founder Heimann Wolff, the mother of Victor Wolff.

The former partner Wilhelm Würzburg devoted almost his entire life to the H. Wolff company. When he retired in the 1890s, his son set up his own business as a fur trader at Leipziger Brühl. His business developed very favorably, but he died at a young age.

Martin Brandt traveled to China as a fur buyer. He had been able to gather unusually rich experiences there and was an excellent fur expert. During the First World War he worked for four years in the commandant's office of a prison camp, he spoke perfect English, French and Russian. When the war broke out, he had married, after the end of the war he took over the raw hide purchase at H. Wolff. When the company was dissolved, he went into business for himself in Leipzig. But he was hardly successful and his wife left him. Martin Brandt died in 1935 as a result of an operation.

Master furrier Paul Larisch found employment with H. Wolff in 1914 after his escape from France, where he had held a leading position at Revillon Frères . First as a workshop manager, he soon became indispensable for the other departments. He became the chief's trusted advisor and had a great influence on all important decisions. After the company went out of business, he and his sons went into business for themselves with a fur retail business.

The owners of the company Schmalz and Weinert were already close friends with the founder of the company H. Wolff. After Schmalz and Weinert had represented the Wolff company in Leipzig for 45 years, the company was dissolved by their son in 1922 and the H. Wolff company opened its own Leipzig branch. Mr Schmalz had long since withdrawn from the business and Mr Weinert had died. His son, Karl Weinert , co-owner of the Bromberg & Co. company now wanted to devote himself entirely to his own company.

Other prominent employees were August Schlegel , Julius Borchard , Gustav Engeler , Heinrich Bachtler , Paul Wendt , Georg Lilga , Wilhelm Brussberg , Carl Drews , Erich Jung , Julius Simonson (Simonson worked for the company for 24 years and later financed the founding of the fur clothing Business Blumenthal & Simonson on Hausvogteiplatz . He left there but again and went to Hamburg to M. Bromberg & Co. ) and Frida cancer , Franziska Lenkord , Olga Meinberg and Mathilde John , Mrs. Unger ( "decades" in charge of fashionable issues) .

The Wolff House

After demolishing seven residential buildings and amalgamating the parcels, between 1909 and 1914 the concentrated overbuilding with wholesale and office buildings took place.

Executed by the architect Friedrich Kristeller , the splendid building for the company H. Wolff was built between 1907 and 1909 according to the ideas of Victor Wolff on the property at Krausenstrasse 17/18, with two large inner courtyards, up to Schützenstrasse 65/66. The ensemble comprised a closed group of three buildings between the years 1909 and 1914 after the demolition of seven residential buildings and the amalgamation of the parcels. The company of the owners of Jewish origin was located in a district in which many other Jewish shops and companies were located were. The company was responsible for the construction work. Joseph Fränkel.

The Landesdenkmalamt Berlin describes the two Wolff houses:

“The almost identically designed facades on both streets express the typical organism of a very versatile commercial building. Shops were originally housed on the ground floor, while the more spacious business premises are on the main floors above. The decoration of the street fronts takes a backseat to the effective rhythm of the pillars. The division of the façade into three horizontal areas, characterized by cornices and a series of arches, pleasantly softens the strong verticality. The interior has been changed a lot by the renovation in 1937-38. The only exception is the stairwells with a very elegant main staircase. "

The rear entrance on Schützenstrasse is just as representative as the front entrance. Although modernized, large parts of the original stone facade have been preserved. The six-story building is now registered as a monument. The main lobby had a bronze entrance door, the floor was marble, and there were mirrors on the walls. The ceiling was made of carved wood. The construction costs amounted to 1.2 million marks.

Philipp Manes remembered his visits as a smokers merchant in the premises of the company H. Wolff:

“The purchasing offices, the large and precious fur warehouse and the model room have been housed there since 1908. The actual sales rooms, the domestic warehouse, the Berlin and foreign departments, expeditions and window rooms are connected, and now the workshops for fur and fabric coats follow in light-flooded rooms. This is followed by the tail turning shop , the refining rooms , the preservation department and the cloakroom serving commercial and technical staff. "

It was planned from the outset to rent half of the building to other companies. Numerous fabric manufacturing companies were represented in the Wolff building complex. The owners of Cohen & Kempe , who “sold a good piece of goods very cheaply and in large quantities”, had their “heyday” there from 1925 to 1930. Even Arnold Zeilinger , fur models, touting his "Fur coats and jackets in the middle price range" in 1926 with "Schützenstr. 65/66 (in the H. Wolff house) ”. Other well-known tenants were the fashion goods company Hermanns & Froitzheim , costume and ready-made fabrics Dick & Goldschmidt , fashion house Ahders & Basch , the women's coat factory Kraft & Lewin , the sales office of the Krefeld silk ribbon weaving mill Krahnen & Gobbers , the textile company Heymann, Welter & Co. and the insurance company Bleichröder & Co .

Under the National Socialists, in 1936, the mortgage lender, Berliner Victoria-Versicherung , suddenly and unexpectedly demanded the immediate repayment of the entire loan amount. The Wolff family had no choice but to agree to the required foreclosure auction. On May 26, 1937, her lawyers signed an agreement under which ownership of the building was transferred to the Reichsbahn for 1.8 million marks, not Victoria itself. After deducting all costs, Fritz Wolff, Victor's son, remained the owner at the time in 1629 Mark.

When, after the war, in January 1949, the Deutsche Reichsbahn wanted to claim their ownership of the building, it was now in the territory of the Soviet occupation zone , it was refused: The former Reichsbahn did not have the building in what it claimed , "Acquired fully lawful transaction" but through a foreclosure sale in the Nazi era.

The architect Ferdinand Kalweit had assessed that about half of the house roof had been destroyed in the war. This was probably the result of a direct bomb strike in the neighboring house at Krausenstrasse 15/16, of which only a heap of rubble was left. After the founding of the GDR, the building came under the responsibility of the so-called German Treuhandstelle for the administration of Polish and Jewish assets in the Soviet occupation sector .

In October 1990, after German reunification , shortly before the deadline, the heirs formally submitted their claim to the house to the Office for the Regulation of Open Property Issues (AROV) . In December 1995 the family got the building back; at the same time she sold it to the Federal Republic of Germany for 20 million marks. Today it is administered by the Federal Agency for Real Estate Tasks and is one of the offices of the Ministry of the Environment . Today's Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure , which had its headquarters at Krausenstrasse 17-18 in 1990, still has a few offices there.

Dina Gold, great-granddaughter of Victor Wolff, granddaughter of Herbert Wolff, daughter of Aviva Gold (born Annemarie Wolff, 1922–2015), published the first, 2016 the expanded edition of the book Stolen Legacy , in which she did not quite Uncomplicated recovery of family property - one of the largest land reclaims ever made to the Federal Republic of Germany - and describes their research and names the institutions and people involved in the expropriation.

Since July 2016 there is a board at the entrance at Krausenstraße 17, in English and in German:

“The Wolff House

Krausenstrasse 17 was built in 1909 as the headquarters of the H. Wolff fur company, one of the oldest Jewish fashion companies in Berlin, founded in 1850.

During the Nazi era, ownership of this property was forcibly transferred to the Deutsche Reichsbahn. After reunification, the Federal Republic of Germany acquired the property from the Wolff heirs in 1996.

The building is listed as a monument. "

- The Wolff House in 2018

literature

- Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy - Nazi Theft and the Quest for Justice at Krausenstrasse 17/18, Berlin . 2nd revised and expanded edition. Ankerwycke Books, USA 2016, ISBN 978-1-63425-427-4 (English)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy , p. XIX (Dina Gold's ancestors); S. XXI (Wolff family tree).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 4. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 1–10, 86 ( → table of contents ).

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 2. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 23a ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

- ^ A b Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 1. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 8, 167–168.

- ^ A b Philipp Manes: Fur manufacture and skinning . In: Benno Marcus (Hsgr.): Großes Textil-Handbuch , Berlin, undated (1927), pp. 720–726.

- ↑ Philipp Manes: The Association of Berlin Smoking Companies EV - Attempt at a Story 1. Continuation. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 58, Berlin and Leipzig, May 16, 1929.

- ↑ Without an author's name: The Berlin fur industry . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt May 10, 1932, p. 2.

- ↑ Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, p. 238-239 .

- ^ Heinrich Lange, Albert Regge: History of the dressers, furriers and cap makers in Germany . German Clothing Workers' Association (ed.), Berlin 1930, pp. 170–171, 180.

- ^ A b Philipp Manes: Review of the year . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt Nr. 1, Berlin and Leipzig, January 3, 1922, p. 3.

- ↑ Philipp Manes: The Association of Berliner Rauchwarenfirmen EV - attempt at a story . 25. Continuation. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 82, Berlin and Leipzig, July 11, 1929.

- ^ A b c d e Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 3. Copy of the original manuscript. Chapter H. Wolff jr. & Co. , pp. 215-216. ( → Table of Contents ).

- ↑ a b Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . Pp. 17-18.

- ^ BP Bukow: Forays through the branch. 50 years of N. Händler & Sohn, Leipzig . In: Die Pelzkonfektion Nr. 1, Berlin, March 1925, p. 15.

- ^ Jewish businesses in Berlin 1930-1945 .

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . P. 22.

- ^ Mail Dina Gold, Washington v. 20th February 2018.

- ^ Heinrich Lange, Albert Regge: History of the dressers, furriers and cap makers in Germany . German Clothing Workers Association (Ed.), Berlin 1930, p. 112.

- ↑ www2.hu-berlin.de: Jewish Business in Berlin 1930.1945 .

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . Pp. 38-39, 85.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 1. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 89.

- ↑ a b c d Daniela Breitbart: Dina's struggle for inheritance . In: Jüdische Allgemeine , November 26, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 4. Copy of the original manuscript, chapter Martin Brandt , pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Paul Larisch: The German fur industry from 1900-1940. Your story . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Hermelin-Verlag, 1960 No. 6, Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Leipzig. Pp. 265-266.

- ↑ a b c www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de, Landesdenkmalamt Berlin: Commercial building Krausenstrasse 17 Schützenstrasse 64 . Last accessed March 13, 2018.

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . P. 18.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 4. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Advertisement dated October 16, 1926 . In: Neue Furzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung .

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . Pp. 29, 62.

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . Pp. 57-64.

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . P. 97.

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . P. 182.

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . P. 115.

- ↑ Dina Gold: Stolen Legacy . P. 304.

- ↑ BMUB - Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building & Nuclear Safety: A memorial plaque on our office building at Krausenstrasse. 17 in Berlin is a reminder of the eventful history of this place. Photo of the plaque. Retrieved March 8, 2018.