Bruehl (Leipzig)

Scroll back in time:

The Brühl is one of the oldest streets in Leipzig . Up until the Second World War it had the reputation of being the “world street of furs ”, it was the most important street in the city and contributed significantly to Leipzig's world reputation as a trading metropolis. For some time, the tobacco industry companies located there generated the largest share of Leipzig's tax revenue. In the building of the inn to red and white lion was Richard Wagner was born. Most of the Brühl was destroyed in World War II. In the GDR it was characterized by high-rise residential buildings in the modernist style and partly renovated old buildings. After the fall of the Wall , some houses got their Art Nouveau facade back, and new buildings were built in contemporary postmodernism . The demolition of the high-rise residential buildings on the Brühl resulted in a considerable building desert in the city center. Adjacent shops complained about a sharp drop in sales, property owners complained about the increasing number of leases. In autumn 2012 the vacant lot was closed by the Höfe am Brühl and the street partly regained its importance as a central shopping street, which it already had between the world wars.

location

Location in urban space

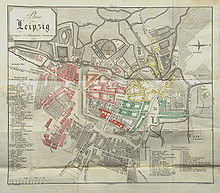

The Brühl (official street code 01009) is a residential street in the northern old town of Leipzig. From the western Richard-Wagner-Platz the street leads past the southern cross streets Große Fleischergasse , Hainstraße , Katharinenstraße , Reichsstraße , the crossing Nikolaistraße and the Ritterstraße , and flows in the east into the Goethestraße.

The side streets branching off from Brühl towards the north are Nikolaistraße crossing the Brühl, the street Am Hallischen Tor opposite the Reichsstraße and the Ritterpassage as an extension of the Ritterstraße. The Brühl runs for a length of about 580 m from west to east, but bends slightly to the south-east at Reichsstraße.

The even house numbers are on the south side of the street, the odd ones on the north side.

Public transportation

The Brühl can be reached by public transport via the tram stops at Tröndlinring in the north-west (stop “Goerdelerring”) and at Willy-Brandt-Platz in the north-east (stop “Hauptbahnhof”); behind it lies Leipzig Central Station , which is connected to destinations all over Germany.

Private transport

The Brühl can be accessed by motor vehicle via Goethestrasse, the maximum speed is 20 km / h. Short-term parking spaces are available to a limited extent in the restricted parking area. In the western course of the street, the Brühl is a pedestrian zone . There is no bike path.

history

Importance as a fur wholesale route

Friedrich Schiller already knew about the variety of fur offers on the Brühl. In a letter to the publisher Georg Joachim Göschen in 1791 he wrote: “My doctor definitely wants me to never go out without fur this winter, and I still don't have one. I suppose I can best get hold of it in Leipzig, and you must be good enough to do it. My favorite fox is because I don't want him to be either too good or too bad ... "

When the name “Brühl” became the epitome of the Leipzig fur center has not yet been investigated. What is certain is that it had long been in common use in the 1920s. In the catalog for the international fur trade exhibition IPA in Leipzig in 1930 it was said: “If one speaks of the“ Brühl ”anywhere in the international tobacco industry, one does not mean the venerable street in Leipzig, but the tobacco trade in its entirety. One speaks of "Brühl usages", "Brühl tendencies", of "Brühl intervening" or of his temporary reluctance. In short, the "Brühl" has been the world power in the tobacco industry since time immemorial. It is an economic structure with a distinctive character and unity that hardly any other industry in the world can show. "

“The name of the Leipzig fur wholesale street -“ the Brühl ”- has become a symbol in two senses. At the same time, it includes the side streets involved in the growth of trade and commerce, in particular Ritterstraße, Nikolaistraße and Reichsstraße, and also puts everything in the spotlight of those who deal with the meaning of the word that belongs to the tobacco industry. ”(Industries - Subject index, 1938)

The unforgettable “mad reporter” Egon Erwin Kisch describes the place from a different, more satirical perspective: “The owner of the cave camp tried to hunt a catch out in the open jungle on the Brühl, now he is hoping the prey in his den to obtain… ”His guest“ cannot speak German (the pack of people is divided into packs that speak different languages) and knows the pastures of Leipzig, he has brought a hunting friend, the “ commission agent ”, so that the fur does not get over his ears will be pulled. "

In a travel guide from 1930, the Brühl is described as one of the strangest shopping streets in a big city: “One fur shop lies next to and above the other, truck after truck are loaded with furs. But the strangest are the customs ... ”, one of them was standing on the Brühl . There were many reasons for this: business deals, acquisitions , the exchange of information or just maintaining social contacts. Not only did at least one representative from every Leipzig tobacco shop come here when the weather was fine, representatives from the dressing and dyeing, furrier and fur manufacture came to keep themselves up to date .

In contrast to the Leipziger Messe, which had developed into a sample fair, the tobacco trade largely retained the goods fair, due to its individually different products dictated by nature, no fur and thus no clothing item is exactly the same. The characteristics of the Brühl were: It represented a goods market, on which the tobacco goods fairs (goods fairs) were held three times a year - on the old trade fair dates New Year, Easter and Michaelmas (29 September). At the Easter fair, eight days after Easter, "novelty exhibitions" took place, there were auctions and a fur fashion show, so that one industry event replaced another almost all year round. When the vaults on the ground floors of the houses were replaced by the palaces of the sample fair around 1900, the Brühl remained the only market operation.

Early history and the Middle Ages

The Brühl, initially Bruel, was part of the Via Regia and arose at the intersection with the Via Imperii , both of which were particularly privileged imperial roads . The important road connection with the city of Halle already meant that there was always a center of trade there. At the western end of the Brühl, on the site of today's Richard-Wagner-Platz, the first Slavic market (later called Eselsmarkt) and the Slavic settlement of Lipsk, from which the city of Leipzig later developed , probably formed in the 7th century . For the 10./11. In the 19th century, there was evidence of the first merchants' and craftsmen's settlements in the Brühl / Reichsstraße area. On the corner of Katharinenstrasse, the Katharinenkapelle was consecrated in 1233 and stood there until 1546.

The Parthe originally flowed through what is now Brühl, but it has been relocated several times over the years. With the construction of the city wall, probably between 1265 and 1270, the street was given the name Brühl , which means something like moor or marshland. However, excavations have shown that swampy land could only be found north of the road and that the name Am Brühl would have been more appropriate. However, the street was first mentioned in writing as "Brühl" around 1420. The street ran in the north of the city in an east-west direction and became a dead end due to the construction of the city wall at its eastern end. In the west of the Brühl was the Ranstädter Tor , from which the Hainstraße led to the south, in the north was the Hallische Gasse, which led to the Hallisches Tor , the Gerbervorstadt and the road to Halle. A little later, probably in the 16th century, a small lane was built between the Ranstädter Tor and the Hallisches Tor, which initially led to the Hallesch Pförtlein for pedestrians . Plauensche Strasse later developed from this .

Brühl as the national route were up to 1,284 imperial until probably after 1350 in the suzerainty of the Bishop of Merseburg arrived. Some properties near the Brühl / Reichsstraße intersection were listed in the jury books of the 15th and 16th centuries. Century as lying on the mountain . This points to a place where justice was done. These were the properties Brühl 44 (later the location of the Zum Roten Adler brewery ) and Brühl 34 to 40, owned by the Breunsdorf family in 1542, on which the large Ausspanngasthof Zum Roten Löwen stood in the 15th century , from which the house continues had his name.

With the adventurous travel novel “ Schelmuffsky ”, a literary memorial was set for the “Red Lion” . Thrown out because of bill cheating and other activities, Christian Reuter wrote his anger about the innkeeper family Müller from the soul. In the 20th century, Günter Grass recalls the work on the papal index several times, especially in his novel The Tin Drum .

In the east of the Brühl there was a bailiwick , similar to a fortified defense yard. In 1262 a chapel dedicated to St. Mary was mentioned in this bailiwick. The lords of the house, the von Schkeuditz , died out around 1263. After that, the king's chamber fell to the Bishop of Merseburg . Presumably, a part of the property, which included the current properties Brühl 73, 75 and 77, was separated at that time and given to private individuals as a fief . A few years after the founding of the university , the Bernhardinerkolleg (a foundation of the Cistercians ) moved into the grounds of the bailiwick on plots 75/77 and built new buildings.

Already in the 12th and 13th centuries there was a dense development on the Brühl. In the direction of the city wall, which ran parallel to the Brühl to the north, there were farms and stables for horses. City fires destroyed the houses on the Brühl in 1498 and 1518, but they were repeatedly rebuilt. Due to its location, the Brühl was a stowage space for goods and travelers to and from the north. The houses were therefore designed as inns and warehouses. Due to its great depth towards the city wall, the north side in particular offered space for many courtyard buildings and warehouses.

The trade in furs and leather took place mainly near the Brühl / Reichsstraße junction, while wool, cloth and linen were traded more in the western part of Brühl (around the donkey market). This division remained until the middle of the 19th century.

One of the first documented craftsmen in Leipzig was a certain Heinrich the furrier and the master furrier Andreas "pellifex" is mentioned as councilor in 1335, a separate guild of furriers was only founded in 1423 at the urging of the city. As early as 1419 there was a fur house on the Naschmarkt for trade in Leipzig . Many of the tobacco shops used the numerous inns on the Brühl to do their business there. Boards or herring cans in the courtyards on the Brühl served as a counter. The council patent dated October 5, 1594 warned against unfair business conduct, "do not hide the smallest goods and types ... under the best ..." only after the start of the sale was allowed.

At that time, Leipzig was not yet of great importance in the tobacco shop and furrier trade; Wroclaw in Silesia and Strasbourg in Alsace were the leading European fur trading centers. Trade on the Brühl experienced an upswing after Elector Friedrich I issued a letter of protection for all Leipzig Jews in 1425. Long-distance trade in furs, in particular, was often carried out by Jews in the Middle Ages.

Early modern age

In 1501, the Leipzig council commissioned the first water pipe (made from pine trunks), which also supplied a public fountain on the Brühl.

The mayor of Leipzig, Hieronymus Lotter , who came to fame as a master builder from Nuremberg, carried out his first order for the city of Leipzig on the Brühl. In 1546 he built a granary (demolished in 1702) on the site of the building that housed the St. Bernard College until the Reformation was introduced in 1543 . In 1546, the city of Leipzig bought the land for 20,000 guilders from the margrave , who owned the property after the secularization . Apparently the council was satisfied with Lotter's work and was commissioned to build the Rannische Badestube at the western end of Brühl and the corner of Fleischergasse . The bathhouse was canceled in 1825, making the house behind it Blumberg to place before the gates Ranstädter free standing with a side wing. In 1832 the Blumberg house was expanded and given a classical facade based on a design by Albert Geutebrück . The house got its name from its first owner, Tiburtius Blumenberg. The large attribute was only added after 1714, after its owner at the time also ran a house at Fleischergasse 6 as Kleiner Blumberg .

From 1727 to 1734 the Neuberin performed with her theater troupe in the Großer Blumberg house . Together with her husband Johann Neuber and Johann Christoph Gottsched , she ran the Neuber'sche Komödiantengesellschaft there and performed dramas in high German. About 140 years later, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche regularly stopped by at Großer Blumberg, saying that Leipzig food is “the least bad” here.

In 1554 the Hanseatic League held the tobacco trade in Leipzig at its Hanseatic Conference in Lübeck to be more important than that in Novgorod . In the 16th century, sources mentioned house names for the first time, including the inns Zum Roten Ochsen and the Goldene Eule (Brühl 25, innkeeper was Hans Fruben from Schönau in Silesia in 1532 ). When the Golden Owl was reopened in February 1920 after the house had been rebuilt in the “sober, simple iron and concrete style”, the wall depictions recalled Goethe, Kätchen Schönkopf, Schiller, Wagner and Napoleon and also paid homage to the fur trade with verse. Other well-known inns were Der Kranich and the Grüne Tanne (formerly located on Brühl 323/324, today Brühl 13). The coffee house in Haus Goldener Apfel (Brühl 327 across from the Romanushaus) was very popular with diamond and gemstone dealers.

The first opera house was opened in Brühl in 1693 and the Romanushaus was completed a few years later in 1704 .

The granary at the eastern end of the Brühl was demolished in 1700/1701, and the Georgenhaus was built in its place as a "breeding and orphanage". Originally the St. Georgen Hospital was located in Rosentalgasse after 1212, and later at other locations. It was used to keep and care for prisoners, orphans and the mentally ill.

In 1743, sixteen merchants met in Leipzig to found the Großes Concert concert association. They initially financed 16 musicians, their first concert was on March 11, 1743. From 1744, the concerts took place in the Drey Schwanen , an inn at Brühl 7, where carters from Zwickau had stopped by in the 16th century . When it moved to the cloth merchants' exhibition center ( Gewandhaus ) in 1781, the orchestra was given the name Gewandhausorchester .

In 1752, the Leipzig Council prohibited unpacking the goods more than three days before the start of the trade fair. Fur traders from London , Koppigen , the area around Brody , Hamburg , Konigsberg and Breslau complained that they had no trade with pepper or crockery and would have their big fur bundle not only unpack and ventilate the skins, tap and size. After a long hesitation, the advice gave in: the tobacco merchants were allowed to unpack from the Monday before the start of the fair, but not yet sell.

Johann Gottlob Schönkopf, father of Anna Katharina Schönkopf , Goethe's early love (it lasted from 1766 to spring 68), had his wine bar at Brühl No. 326 (today No. 19), where Goethe also had his lunch table during his studies in Leipzig took: "I really stayed with you after Schlosser's departure, gave up the Ludwig table and found myself all the more comfortable in this closed company as I liked the daughter of the house , a very pretty, nice girl, and gave me the opportunity to exchanging friendly looks, a comfort that I had neither sought nor accidentally found since the accident with Gretchen. "

Although the German and foreign tobacco merchants met three times a year at the trade fair in Leipzig , there were hardly any tobacco companies in Leipzig . In 1784 there were only nine shops selling tobacco goods and leather in the city, of which only two are said to have remained at the end of the Napoleonic Wars . In order to revive the trade fair business, which had declined after the wars, in 1813, against the resistance of the local merchants, six “foreign Jews” were admitted as mess brokers for the first time . This office granted the owners permanent right of residence in Leipzig and was therefore very much appreciated. It then took another 42 years until the Kramer Guild accepted the first Jew as a member in 1855.

From the beginning to the middle of the 19th century, there were also linen , gut and product stores (agricultural products) in large numbers on the Brühl, especially in the eastern part, in addition to tobacco shops . The main fairs for fur, hare skins , pig bristles and horsehair were to be found on the Brühl at that time .

Over time, however, the Brühl specialized in the tobacco trade . The often Jewish traders initially found accommodation in Judengasse in the Ranstädter suburb. When this had to be demolished at the end of the 17th century, there were special Jewish hostels at the Brühl. Since 1687, the Jewish fair visitors mainly stayed in the "Bruel", later called Brühl, and it is known that almost exclusively Jewish merchants had their fair camps there. At the masses, Leipzig evidently gave the impression of a Jewish city, at least that's what Johann Gottfried Leonhardi called it in his description of Leipzig in 1799.

Already at the end of the 17th century, the Peißkerische Haus am Brühl was called "the old Jewish hostel". In 1753 , the “Brodyer Schul” or Tiktiner synagogue for Jews trading in Leipzig was built in the Blauer Harnisch , today Brühl 71 . The Jewish tobacco merchants mostly came from Brody, Galicia, Lissa ( Leszno ) and Sklow via Hohe Straße . Along with Lemberg, Brody was the most important trade center in Galicia, the merchants from the Brody fur trade center were among the most important trade fair visitors and not only contributed to the creation of a down-to-earth tobacco industry, but also to the revitalization of Leipzig's Jewish community. Contemporary official reports show that the success of the Leipzig trade fairs often depended on the extent to which the Brody trading houses participated.

On the site of the medieval St. Katharinen bathing room , Brühl 23, there was later a hostel, in which mainly Plauen merchants and carters stayed during the fair. From 1804 you could officially call yourself the Plauenscher Hof . For two years it was run by Ernst Pinkert (1844–1909), who constantly presented exotic live animals in the two restaurants he ran. In 1878 he gave in to this inclination completely and founded the zoological garden. The Plauensche Hof existed until 1874, when it was replaced by the Plauen Passages . There were still restaurants here, including Louis Pfau who ran the First Viennese Café here after 1900 .

Shortly after 1900, the Weissenfelser Bierhalle (owner Wilhelm Moosdorf) was built on Brühl 74 with an elaborate three-storey facade painting. However, the regional beer could not hold its own against the strong competition, especially from Franconia and Bavaria . As early as the 1920s, furs were traded here, as in the neighboring house on the left.

A few houses further on, Brühl 80 / Goethestraße 8, built in 1857, called Georgenhalle from 1859 , were the meat halls (destroyed in 1943). After Chancellor Bismarck had assigned the Reichsgericht Leipzig as the location, it met in this building from October 1879 to 1895. The café that was also established there was called the Prince Reich Chancellor , and the wine bar in the cellar next to the wine wholesaler located there with mainly Austrian and Hungarian wines Esterházy keller (owner August Schneider). It later became the wine cellar , which around 1930 also ran one of the city kitchens.

industrialization

some time by the ethnologist Moritz Lazarus

The Brühl, which had housed the Jewish trade fair guests for a long time, became the center of a year-round tobacco shop. The Greek Constantin Pappa (1819) was followed by merchants of German and other nationalities. Nevertheless, a large part of the importance of the Brühl at that time was still due to the international connections of the Jewish industry members. While the Leipziger Messe changed more and more into a sample fair, this was hardly possible for the fur trade with its individual products, the buyer wanted to see the goods and take them in hand, at best the garment manufacturer could offer goods that were almost the same. This cleared the way for the rapid upswing of the Brühl with its large fur camps. In addition to the fur traders, there were also furriers and the offices of the fur finishers, who all had their tanneries and dye works outside by flowing waters. In 1815 there were only two tobacco shops on the Brühl, but in 1875 there were already 70, more than the Brühl houses had.

The first Jewish banker in Leipzig was de facto Joel Meyer auf dem Brühl 25. He had had an “office” there for decades when his bank was licensed in 1814 by the Russian city commander Colonel Prendel . Isaak Simon also owed his admission to Brühl 39 to this. Officially, there was only the Jewish bank of Adolph Schlesinger & Jakob Kaskel, Brühl 34, before the wars of liberation . After seven years, the partners separated; Dresdner Bank emerged from the Dresdner branch .

In 1820 with the Psalms of Giacomo Meyerbeer of Temple Beth Jacobs in Leipzig Paulinum inaugurated. Until then, the Brody Jews had a place of worship in the quarters of the mess broker Marcus Harmelin in the Blauen Harnisch , Brühl 71.

With the construction of the first economically important railway line between Dresden and Leipzig in 1837, Leipzig's importance as a supra-regional trading center grew. At the same time, the fur industry and the wholesalers supplying it expanded around the Brühl. This upswing was made possible by increasing specialization and, crucially, by the invention of the fur sewing machine . In particular, fur dealers who specialized in long-distance trade, as well as cloth and fashion dealers, were able to do good business in their business premises and houses on the Brühl outside of the trade fair hours and gain wealth or even wealth. The Brühl increasingly changed its face, old inns gave way to warehouses for fur traders and workshops and salesrooms for furriers.

Moritz Schreber , known as the “father of allotment gardens” , made the first notable changes . In 1844 he had a tobacco shop built at Brühl 65.

After 1860 the Brühl changed its face when it was converted into a modern shopping street. The structure typical of Leipzig with its inner courtyards and passageways was retained. After the work was completed before the First World War , the Brühl was transformed into a representative business district.

August Lieberoth founded a banking and freight forwarding business (August Lieberoth Bank) at Brühl 7–9 in 1861. Both businesses remained in family ownership until the bank was closed in 1947 and the shipping company was expropriated in 1953.

A special kind of incident took place on March 20, 1865 at the Brühl. From a police report: “The furrier journeyman Otto Erler testifies: The same person (meaning Karl May , the later author of Winnetou and Old Shatterhand) went to the shop in the afternoon (under the name Hermin), where only Erler's mother-in-law was present, Brühl No. 73, I bought a beaver fur with beaver lining and the same surcharge and black cloth cover for 72 thalers and given the order to carry the fur to his apartment at Frau Henning's. Erler did this too, met the alleged Hermin, gave him the fur and now waited for payment. Hermin took it out to the room to show the fur to his hosts, but never came back. ”Karl May put the fur coat on the pawn shop for ten thalers . Along with other offenses, he was sentenced to 49 months at a workhouse , of which he served three and a half years in the Schloss Osterstein workhouse .

In the middle of the 19th century, the so-called criminal table stood in the cellar bar "Zur Guten Quelle" on the Brühl . Politicians and scholars who had come into conflict with the system of that time met here. In opposition circles, however, it was considered an honor to be invited there. Significant names are carved into the tabletop, which is in the City History Museum . The natural scientist Alfred Brehm and the politician August Bebel , presumably also Wilhelm Liebknecht, sat there .

called "Pelzkirche".

The office building, also officially known as Gute Quelle , was built by the fur traders E. and G. Lomer (1876; see picture). The building with the neo-Gothic facade was nicknamed " Pelzkirche " by the people of Leipzig . The operators of the restaurant with the stage located there changed several times, in 1921, for example, the Blaue Maus (owner Mielke) was located here , in 1929 it was called Platz'l (owner Max Schütze) and had 900 seats.

Heyday and crises

In 1870 the Allgemeine Deutsche Creditanstalt (ADCA) acquired the St. Georg orphanage at the east end of Brühl for 370,770 gold marks . The building was in a dilapidated condition and was demolished in 1872. This opened the Brühl to the east and connected it to Goethestrasse. The main front of the new store built by ADCA was on Goethestrasse. Emil Franz Hänsel won the tender for a bridge over the Brühl in 1933 together with J. Schilde. The box-shaped bridge connected the buildings of the Allgemeine Deutsche Creditanstalt.

In 1882, the Leipzig Horse Railway laid the Lindenau tram route across the whole of Brühl. From 1897 the line was electrified by the successor company, the Great Leipzig Tram . The line existed until 1964.

In the years around 1900 Leipzig could be described as the center of the tobacco trade in the world , around 1913 around a third of the "world harvest" of tobacco products was traded through Leipzig. The smell at the Brühl was typical, caused by preservatives such as camphor and naphthalene and the sweet smell of the raw pelts. Another characteristic of the flair on the Brühl part, where the fur trade flourished, was the hustle and bustle on the street and in the courtyards. The courtyards usually extended through the entire block of houses, so that the horse and carts could deliver the goods without turning and drive out on the opposite side. Some of the courtyard floors behind the Brühl and Reichsstraße were furnished with magnificent wooden galleries. After 1900 the courtyard galleries were less used for relaxation, but were mainly used to knock out the furs to remove dust and, above all, to protect them from moth infestation. The walls of the courtyards were often painted blue, the blue-tinged “blue” winter goods are valued more highly in the fur industry than the “red” pelts that were produced before or after the season.

So-called market helpers pushed onto walkie trucks large, in lichens (large baskets) packed quantities of goods from farm to farm or loaded them into vans that took them to the processing sites in the vicinity of Leipzig. Dealers in their typical long white coats tried to intercept their potential customers before they possibly disappeared into the warehouses of the competition. Above all, people met there for a conversation, the “standing convention”, there was generally a friendly tone, after all, they also did business with each other. Not only in bad weather you sat in the surrounding cafés and restaurants, such as the Reich Chancellor (Brühl / corner of Goethestrasse) and later in the Goldenen Kugel and in Café Küster (both Richard-Wagner-Strasse) and in the kosher restaurant Zellner (Nikolaistrasse) . After many furrier shops had opened in the second half of the 19th century, the Brühl resembled a bazaar . On the street, bundles of fur hung up in front of almost every house indicated the occupation of the residents. In the 1860s and 1870s, there was traffic that was sometimes perceived as life-threatening at the time of the fair, and the Easter fair lasted a remarkable six weeks. If a car wanted to pass the Brühl near Nicolaistrasse, a police officer often had to make room first. The Greeks, who were still “picturesquely” dressed at the time, and the “Old Testament caftan wearers” from Russia were particularly striking. But Armenians, English, French and others were also represented in large numbers.

Gloeck's house was built in 1909/1910 on Brühl 52, corner of Nikolaistraße. Before that, the Zum Walfisch inn stood at this point. The Leipzig architect Otto Paul Burghardt built the house for the fur trader Richard Gloeck . The shell limestone facade isadorned with sculptures of peoples from all over the world as symbols of the global tobacco trade. The house was popularly known as the Chinchilla House . The building was renovated in 1996. In 1909 the Gasthof zum Strauss was demolished. The resulting gap made it possible to continue Nikolaistraße to the main train station . In 1914, scouts were only able to buy their scout equipment from the men's and boys' fashion store Hollenkamp & Co. (Brühl 32 / corner of Reichsstrasse) by submitting a certificate.

The Brühl was now not only a wholesale place for fur skins, but also a center for private fur shopping. In 1926 a London trade journal reads: "I consider the Brühl with its beautiful fur shops to be the most beautiful fur district in Europe". After the Berlin trade fair office had organized a German fur trade fair in the radio hall at the Berlin radio tower in 1926 , representatives of the city of Leipzig from Brühl and the Leipzig trade fair office began to plan a fur show that had never been seen before in the global tobacco industry. In 1928, the association moved to Brühl No. 70 to host the exhibition . Due to the global economic crisis of 1929, the International Fur Exhibition (IPA) was not opened until May 31, 1930. Most of the IPA was located on the rented exhibition grounds, but the Brühl also offered numerous attractions. Show workshops, historically furnished backyards, special exhibitions such as the exhibition Fur fashion through the centuries , designed by Valerian Tornius and Rudolf Saudek , not only delighted the specialist audience. Until September 30, 1930, the Brühl was a true-to-life replica of times long gone: the red ox , the three swans , a freight forwarding and packing yard, the old stone pavement to the trademark of the old fur traders and bundles of fur in front of the entrances of the fur trading houses. Unfortunately, the execution took place in the worst time of the Great Depression, with around one million visitors, the attendance was only half as high as expected. Nor did the people of Leipzig visit the exhibition, "they said if you want to saw fur, yawn on the Brühl, it doesn't cost anything ".

The Brühl achieved its greatest density with 794 tobacco shops in 1928, an average of seven per house. The so-called “silent porter” indicated 34 fur businesses on enamel signs mounted on top of one another in the Blauer Hecht alone , which is postal address to Nikolaistrasse. This house held the record, but 20 companies and more under one roof were not uncommon. Hardly any of the small traders also had their apartment here at the same time. The families of the top-selling Jewish tobacco merchants lived, for example, in southern Gohlis , in Waldstrasse - and in the music district .

From 1926 to 1930 the Brühl had regained its international reputation after the difficult times of the First World War and the subsequent inflation. With a raw material turnover of 500 to 600 million Reichsmarks, he dominated around 30 to 35 percent of the world market during this time. However, the continuing global economic crisis made 1931 a year of bankruptcy for many fur traders. With a loss of 40 to 50 million Reichsmarks , around 30 percent of traders had to give up their business. The exchange controls in particular bothered many fur traders. As early as 1930, the Assuschkewitz AG brothers at Brühl 74 no longer received any loans from Deutsche Bank without real security. In 1934, the company was able to take out a few mortgage loans, until in 1935 it ran out of bank capital. The firm of D. Biedermann , who was considered the richest man by far am Brühl, after his death in 1931 liquidated , dissolved the Chaim Eitingon AG after the death of the owner 1,932th In 1934, Allalemjian & Mirham was given notice of all loans from Deutsche Bank. Even the old, traditional fur trading company Lomer had to announce the liquidation. Nevertheless, the opening words of a report in which the stability of the Leipzig fur industry was confirmed: The Brühl in the storm remains the Brühl in the storm .

When the NSDAP came to power in 1933, the tobacco trade faced further problems. For political reasons, the fascist leadership limited the import quota for goods from the USSR so low that trade was no longer worthwhile for both sides. It was precisely the trade with the East that had made Leipzig great, now it was more difficult to get furs; mass unemployment in the tobacco industry was the result. Some experts believed in a professional future in Moscow and applied there. However, the Soviet Union was neither able to employ them nor to pay them according to German expectations.

Some of the best known Jewish tobacco merchants were there

- Julius (Judel) Ariowitsch (1853-1908). His father, tobacco merchant Mordechai Ariowitsch from Belarus , was already a regular visitor to the Leipzig trade fair. Julius (Judel) Ariowitsch's widow, the son Max Ariowitsch and his brother-in-law founded the Ariowitsch Foundation together in 1930. The company at Brühl 71 was forcibly liquidated in 1941.

- David Biedermann (1869–1929), pioneer of trade with Soviet Russia.

- Chaim Eitingon (1857–1932), called "Pelzkönig vom Brühl", founder of the Ez-Chaim synagogue and the Jewish hospital, Brühl 37–39, from Schklow in Belarus, later Moscow, moved to Leipzig in 1917, with an annual turnover in 1926 and 1928 of 25 million Reichsmarks each.

- The Frankel family ; the descendant Jury Fränkel (1899–1971) founded what is still the most important manual of the tobacco trade today.

- Harmelin family (1830–1939) from Brody . Jacob Harmelin (1770–1851) was a regular visitor to the trade fair in Leipzig, in 1818 he was sworn in as a mess broker and set up a Leipzig tobacco company under his name.

- John B. (John [Joel] Berend) Oppenheimer & Comp. (1834), one of the most important tobacco companies in the middle of the 19th century.

- F. Weiss (1893–1982)

- Theodor Wolf (around 1833), taken over by N. Haendler & Sohn in 1874.

If one believes the message from the Reich Association of German Tobacco Manufacturers , which was handed over to the Reich Ministry of Economics on October 24, 1933, after the National Socialists came to power , then the denomination in the fur industry was largely equivalent to Leipzig and the surrounding area in the specified sectors (the fur clothing was mainly in Berlin):

| branch | Christians | Israelites | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco shop | 20% | 80% | |

| Fur clothing | 5% | 95% | |

| Refinement of smoking goods | 85% | 15% | |

| Listed with: buyer groups |

35% | 65% |

Jewish traders on the Brühl were increasingly discriminated against and driven out. In 1935 three Jewish businessmen were forced by the Nazis to walk across the Brühl and other streets of Leipzig with signs around their necks calling for a boycott of Jewish businesses.

The 113 Jews expelled by 1936 alone had a turnover of 93 million Reichsmarks in 1929 . They took their business connections with them to England or the USA , where they founded new companies. In Leipzig, the Jewish population only made up about 2.04 percent, but traditionally the main field of activity was trade. Thus, out of a total of 794 tobacco dealers (as of 1929), 460 were of Jewish descent, i.e. around 58 percent. 2000 people were employed in the Jewish factories and lost their livelihoods. Other businesses that lost their customers went bankrupt. With the Reichspogromnacht , during which the Tictine synagogue burned, it became completely impossible for Jewish traders to continue their business. By 1936, 113 companies that had achieved a turnover of 60 million Reichsmarks in 1931 had migrated abroad, were liquidated or had fallen to “Aryan” entrepreneurs. Three and a half years before the end of the war, in September 1941, a RH wrote in the "Kürschner-Zeitung" that almost three-quarters of the businesses on the Brühl had now been cleared of Eastern Jews and that the Brühl was "once again the center of the European tobacco industry". In fact, however, the anti-Semitic policies of the National Socialists had made the fur trade at the Brühl lose its world fame forever. The last company sign that was brought down was that of Heinrich M. Königswerther, "it now also has a new name".

Second World War and the GDR period

On December 4, 1943, after the heaviest bombing raid of the entire war by British airmen , the Brühl burned down almost completely, although there were hardly any hits in this area. However, the fire spread to the Brühl-Höfe and raged until December 15, 1943. Only nine buildings survived the inferno. The north side between Nikolaistraße and Goethestraße was completely destroyed, the least damage was on the south side. The stocks of goods brought to safety in the cellars were destroyed by a burst pipe. After the end of the war, there were still 170 of the 794 tobacco shops that were previously located in the neighborhood of Brühl, especially in Oelsner's yard on Nikolaistrasse.

After the Brühl was structurally and economically devastated, a new beginning initially seemed impossible. The new political situation made it necessary to develop relationships with new suppliers and customers. Skins were difficult to come by as the poor economic situation meant that more emphasis was placed on meat production. Since 1946, the organization of the tobacco trade has been managed by the German Trade Center Textile Branch Smoke Goods at Nikolaistraße 36. Stadtpelz , a municipal economic enterprise of the city of Leipzig , had its premises on Brühl 54 in 1950. Despite all the problems, the foreign trade company Deutsche Rauchwaren-Export- und -Import-GmbH was founded in February 1958 in Nikolaistraße, later renamed Interpelz . Even before the war, there were considerations to relieve the Brühl by building a building that would take on all common functions. The ten-storey house of Interpelz am Brühl (high-rise Brühlpelz ) was not realized until GDR times and was inaugurated in 1966. Since 1967 the tobacco industry in the GDR has been exhibiting its products in a trade fair building behind it, the Brühlzentrum congress building on Sachsenplatz . In 1960 the first tobacco auction in Leipzig took place after the Second World War (from 1968 in the Brühlzentrum). However, the Brühl had finally lost its reputation as the “world road of furs”.

Most of the fur companies went to the flourishing Federal Republic of Germany, where, with the beginning of the economic miracle, fur sales reached double-digit growth rates and Germany became the number 1 fur consumer country for a long time (today Russia). In Frankfurt am Main in particular, a new fur center with an almost similar charisma was formed around Niddastraße , long known by the industry and still sometimes referred to as the Brühl today. The characteristic there was for a long time the newly emerged dialect of Saxon "Frankforterisch".

At the end of the 1950s there were plans to insert modern, gap-filled buildings, the façade structure of which was based on the historical buildings, between the old buildings that were left over after the Second World War, some of which had already been restored. However, the plans were not implemented and the remains of the old buildings, u. a. the Union exhibition center demolished in the north-western part.

At the eastern end of the Brühl, where the ADCA office building had stood until 1943, the Interhotel Stadt Leipzig was built in 1963 with the addition of further properties in Richard-Wagner-Straße 3–6 . The front of the hotel faced the main train station . The Great Blumberg , which was still badly damaged by the war, was restored to its historical form in 1963/64 with the help of the Institute for Monument Preservation Dresden and Volker Sieg. The Cafe am Brühl (also known as the “Zur Neuberin” inn) was set up on the ground floor .

In the period from 1966 to 1968, three ten-storey residential high-rises, parallel to each other but transverse to the Brühl, were built on the northern side of the Brühl, forming small inner courtyards connected by single-storey low-rise buildings. The connection to Plauenschen Straße was built over. The unconventionally designed Leipzig Information Building was opened in 1969 on the neighboring Sachsenplatz . In addition to dining facilities such as the mocha bar , this building also contained rooms for representative and cultural events. Opposite on the Brühl the Polish Information and Culture Center was opened on February 5, 1969 . The aim of such institutions was, in addition to the exchange of cultures, political education. Here GDR citizens should convince themselves that the People's Republic of Poland was a permanent member of the socialist bloc.

After the turn

In 1993 in Leipzig the discussion about the selling price for Oelßners Hof (Ritterstraße, formerly Quandts Hof ), formerly the center of the Leipzig Fur Center, made headlines. This 3400 square meter passage, which once belonged to the Thorer family of tobacco merchants , wanted to acquire the family of the owners at the time. The city treasurer agreed a price of 20.5 million DM , valuations had gone up to 50 million DM.

The Leipzig information building on Sachsenplatz was no longer used, so in 1996 it was decided to demolish and rebuild the square. A cube-shaped new building for the Museum of Fine Arts was built between 1999 and 2004 . The Leipzig pop-art artist Michael Fischer-Art covered the high-rise apartment buildings on the Brühl with a colorful pop-art film on the occasion of the 2006 World Cup. Another work of art by Michael Fischer-Art is the approx. 3000 m² wall painting on the gable wall of the Brühl-Arkade .

The buildings on the south side of the Brühl between Richard-Wagner-Platz, Katharinenstraße and Reichsstraße to Ritterstraße, which were still preserved after the Second World War, were renovated in the 1990s and some vacant lots were closed with new buildings. The Forum am Brühl was built on the Ritterpassage in 1996 . The seven-storey building complex made of sandstone and granite offers offices, practices and shops with a total area of around 27,000 square meters with over 11,000 square meters. In 1998, at Brühl 33 (formerly Schwabes Hof ), at the corner of Am Hallischen Tor, the Marriott Hotel with the Brühl-Arkade was built according to designs by the planning group Wittstock und Partner from Hanover.

After the end of the GDR there were new ideas to redesign the Brühl. In 1999 a “planning workshop” was set up, in which several architects' offices could develop ideas and concepts. A proposal from Architektur Raum e. V. to maintain the high-rise apartment buildings and to create modern social living space, however, could not prevail. The construction of an inner-city shopping center with partial residential use was now planned. The western area of the new building complex has meanwhile been clad again with the listed aluminum honeycomb facade of the Brühl department store (the so-called tin box in popular parlance ).

On the occasion of the 575th anniversary of the Leipzig Furriers' Guild on August 28, 1998, a memorial plaque was attached to the Brühl's "fur corner": "For centuries, Brühl was the center of the international tobacco trade, also shaped by Jewish traders."

In 2007, most of the apartment blocks and commercial buildings in northern Brühl were demolished. In 2010, in response to protests from monument preservationists and parts of the citizenry, the Brühl department store with its artistically designed original façade, still partially preserved under the aluminum façade, was pulled down. The “Brühlpelz” skyscraper will be used as refugee accommodation from November 2015 to April 15, 2016, during a European refugee crisis , and a hotel will then be built there.

Archaeological evidence

Until 2008, the Brühl was only little archaeologically researched. Unfortunately, no archaeological investigation was carried out during the construction work on the northwestern Brühl from 1966 to 1968. Instead, when the high-rise buildings were erected, a large part of the archaeologically valuable layers was destroyed to a depth of three meters. It was only after the high-rise buildings were demolished in July 2008 that the 17,000 square meter area could be examined. Only a few sections showed a completely preserved layer of layers.

Layers of peat, which were created by regular flooding, could be detected between 1290 and 1390. Historians have previously assumed that the development on the Brühl was created at the same time as the city of Leipzig. Finds at the level of Katharinenstrasse / Plauensche Strasse suggest, however, that there were already loose buildings before the city was founded, according to which the Brühl next to Hainstrasse would be one of the oldest streets in Leipzig.

On the former property at Brühl 31-35, in addition to the remains of the Zum Heilbrunnen house, the foundation walls of an older stone building from the 15th century with dimensions of around 8 × 20 meters were found. This can definitely be seen as a sensation, as there were hardly any suitable quarries in Leipzig and the surrounding area and therefore only small half-timbered houses made of wood and clay were common. Such half-timbered buildings could be proven for the Brühl 27 (Lattermanns Hof) and Brühl 23 (Plauenscher Hof). The Steinhaus am Brühl has not been handed down historically. The size and the expensive construction material suggest that it was a public building or the private house of a wealthy Leipzig citizen.

Street scene

Western part

The north-western part of the street is characterized by the complex Höfe am Brühl shopping center . A retail space of around 45,000 square meters with 130 shops, 70 apartments and up to 820 parking spaces is housed in an area of around 22,300 square meters. In February 2009, the investor in the shopping center announced his will to realize the project after he had previously withdrawn his financing offer for the 200 million euro construction project.

In the run-up to the construction project, there were increasing doubts about the sense of a large-scale project in downtown Leipzig, as there was already a wide range of products and all the larger retail chains were represented in Leipzig. Nevertheless, the dealers in the city center hope for a future revival after the large construction site at Brühl led to a steady decline in sales.

At the Hainspitze , the location of the former cloth hall, a department store of the Primark chain was built in April 2016 . This closed this gap after more than 70 years.

Middle part

Between Reichsstrasse and Katharinenstrasse, behind a green space, offset from the Brühl to the south, is the Museum of Fine Arts in a cuboid new building. In front of it there is a perimeter block development surrounding the museum at the usual eaves height , which has restored the historic course of the Brühl road in this section.

The Romanushaus, which has been renovated with its baroque facade, forms the corner building on Katharinenstrasse. To the southwest, new or renovated residential and commercial buildings connect to Hainstrasse.

Eastern part

To the east of Nikolaistraße, mainly renovated Art Nouveau buildings, such as Gloeck's house , have been preserved. There are also contemporary postmodern buildings , such as the Brühl-Forum in the northeast with the hotel ibis or the Brühl-Arkade complex with the Marriott Hotel on the corner of the Hallischer Tor.

There are vacant lots on the corner of Ritterstraße opposite the Zur Heuwaage building and to the right of the Brühl-Arkade. To the left of Zur Heuwaage is the listed building Brühl 74, formerly the Assuschkewitz brothers . An office building from the 1970s stood on the following property until the summer of 2009, which continued in Goethestrasse. It has since been torn down to make room for the new headquarters of Unister Holding GmbH .

Commerce and gastronomy

In addition to a few restaurants, there are mainly retailers on the Brühl, especially at the intersection with Nikolaistraße and on the south-west side. There are no or few shops in the northwest and southeast. The streams of pedestrians run mainly through Hainstrasse to the tram stops at Tröndlinring and Nikolaistrasse in the direction of the main station.

Richard Wagner's birthplace

Richard Wagner was born on May 22nd, 1813 at Brühl 3, at the Roter und Weißer Löwe inn . The inn, first mentioned in 1656, was named after the heraldic lion of the Landgrave of Thuringia , stripes across white and red , and was the accommodation of the carters from Thuringia . In 1882 the house took on the name Richard Wagner was born in. Four years later it was demolished, but the subsequent building continued to be called the Wagner House . In 1913 the former square at Ranstädter Tor , later Theaterplatz , was named Richard-Wagner-Platz . In 1914 a new building for the Brühl department store was built on the foundations of Brühl 1 and 3 and expanded in 1928. The building initially had curved lines and a natural stone facade. Renewed conversions to the consumer department store on Brühl took place in 1964–66. The building was given an eight-storey extension and a curtain-type facade made of hyperbolic aluminum elements without windows, which earned the department store the nickname “tin can”. It was the largest and most modern department store in the GDR. The facade is a listed building; after the building was demolished, it was installed in the same place and in the same form in 2012 on its successor building integrated into the courtyards at Brühl . Since 1937/1970 a bronze plaque by the Leipzig sculptor Fritz Zalisz at the Brühl department store has been a reminder of the house where Richard Wagner was born.

literature

Books

- Richard Küas: Children from Brühl. Novel. Phönix-Verlag Carl Siwinna, Berlin 1919, book cover, letter

- J [acques] Adler: The Brühl in world traffic and city traffic. No. 17 in the series of publications Leipzig Transport and Transport Policy. Leipzig 1930, book cover

- Gustav Herrmann: One from Brühl. Novel. Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Leipzig 1930, book cover, table of contents

- Waltraud Volk: Historic streets and squares today. Leipzig. Publishing house for construction, Berlin 1981

- Walter Fellmann : The Leipziger Brühl. History and stories of the tobacco trade. Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-343-00506-1

- Birk Engmann: Building for Eternity: Monumental architecture of the twentieth century and urban planning in Leipzig in the fifties. Sax-Verlag, Beucha 2006, ISBN 3-934544-81-9

- Doris Mundus, Rainer Dorndeck: furs from Leipzig, furs from Brühl . Sax-Verlag, Beucha / Markkleeberg 2015, ISBN 978-3-86729-146-0

Magazines

- Plaster and fur. Magazine for the German furrier and plastering trade. Verlag Die Wirtschaft, Berlin 1953–1959

- The Brühl. Trade journal for the tobacco trade, fur clothing, tobacco refinement and fur farming. Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1960–1990, ISSN 0007-2664

- Fashionable line & Brühl. Trade journal for the tailoring, milliner and furrier trade, for tobacco trade, tobacco product refinement, fur animal breeding. Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1990–1991, ISSN 0944-0259

theatre

- SE Vengers (actually Salomon Joel, called "Sally", Gröbel): Ultimo am Brühl . Volksstück, premiered on August 1, 1931 by the Leipziger Komödienhaus in Tauchaer Straße (until 1929 Battenberg Theater). The manuscript seems lost.

- Direction and editing: Frank Witt and RA Sievens; Main character fur trader Stephan Gaborius: Herbert Schall (guest); Wife and mother: Käte Frank-Witt; Son: Hans Flössel ; Commerce Councilor: Joseph Firmans. Stage design: Joseph Firmans.

- From the criticism in a fur specialist newspaper: "[...] Like Gustav Hermann, who published the fur trader's novel" Eine vom Brühl "(Verlag Wilhelm Goldmann, Leipzig) in the Ipa year, is probably also the author behind the Pseudonym hides, a man from the "branch". This is supported by the naivety in the dialogue, at times an artless juxtaposition of jokes and trivialities, and the intimate familiarity with the usages and current big and small concerns of Brühl. [...] The premiere was a complete success with the public. "

- Gustav Hermann, former owner of Rödiger & Quarch , the oldest fur dye factory in Leipzig, also wrote the texts and couplets annually for the fur fashion shows that took place in the Krystallpalast from 1921 to 1926 : “Knowledgeable enough to find the right milieu, and connoisseur of the Brühl, to insert a scene about his people. To the cheers of the industry and the Leipzig public, who crowded to the performances, the performance went on, which always ended with a large demonstration to summarize all the innovations of the exhibitors ”.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Handelsstrasse Brühl is threatened with collapse - shops are closing. LVZ online, archived from the original on March 26, 2009 ; accessed on March 31, 2009 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Walter Fellmann: The Leipziger Brühl . Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1989, ISBN 3-343-00506-1

- ↑ a b c d Unger, Leipzig City Archives: The Leipziger Brühl - His name . In “Brühl” March / April 1967, VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, pp. 9–11

- ↑ The Brühl . In: IPA Internationale Pelzfach-Ausstellung, International Hunting Exhibition Leipzig, Official Catalog, Leipzig, May – September 1930 , pp. 254–270.

- ↑ Gustav Herrmann: Der Brühl, the power center of the German tobacco industry . In: Guide through the Brühl and the Berlin fur industry , 7th edition, 1938

- ↑ EE Kisch: Pelzschau. Brühl in Leipzig . In Die Weltbühne , p. 654, 1930 (secondary source Fellmann: Der Leipziger Brühl )

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Waltraud Volk: Historic streets and squares today. Leipzig. Publishing house for construction, Berlin 1981

- ↑ Dr. Gottlieb Albrecht, Hanover: The Leipzig fur market with special consideration of its tobacco goods trade . Inaugural dissertation at the Thuringian State University Jena, Bottrop 1931, p. 8

- ^ Advertisement from Oscar Wenke in the Carl Hülße company, Leipzig: Exhibition of innovations by the Reichsbund der Deutschen Kürschner e. V., Leipzig. In: Directory of members of the Reichsbund der Deutschen Kürschner e. V., 1928. Verlag Arthur Heber & Co., Leipzig, p. 90 ( book cover and table of contents ).

- ↑ a b c d e f Wilhelm Harmelin: The Jews in the Leipziger Rauchwarenwirtschaft. In: Tradition, magazine for company history and entrepreneurial biography , 11th year, 6th issue, December 1966, Verlag F. Bruckmann, Munich, pp. 249–282

- ↑ a b Dr. Friedrich Schulze: The Brühl . In: IPA Internationale Pelzfach-Ausstellung, International Hunting Exhibition Leipzig, Official Catalog, Leipzig, May – September 1930 , pp. 270–274

- ^ The online chronicle of the city of Leipzig. In: Leipzig-Info.net. Retrieved February 13, 2015 .

- ^ A b c d e Barbara Kowalzik: Jewish working life in the inner north suburb of Leipzig 1900-1933 . Saxon Economic Archive e. V., memories 1 . Leipziger Universitätsverlag, Leipzig, 1999, pp. 9, 65, 67, 150

- ^ A b Horst Riedel: City Lexicon Leipzig . Pro Leipzig, 2005, p. 71f.

- ↑ Information board on the site fence at Brühl 2008

- ↑ Fitz Reinhardt: From a furrier journeyman for whom the masterpiece was made difficult. In. Kürschner Zeitung , Verlag Alexander Duncker, Leipzig approx. January / February 1942, p. 8

- ↑ a b c d e f g Klaus Metscher, Walter Fellmann: Lipsia and Merkur. Leipzig and its fairs. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1990, ISBN 3-325-00229-3

- ↑ Otto-Lindekam-Leipzig: The Leipziger Rauchwaren- und Kürschnermesse in earlier centuries , in Deutsche Kürschner Zeitschrift No. 10, 31st year, April 5, 1934, Verlag Arthur Heber & Co, Berlin, pp. 252-256

- ↑ Timeline of the history of the Jews in Leipzig up to 1933, on the juden-in-sachsen.de Internet portal. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 6, 2009 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d Ulla Heise: A guest in old Leipzig . Hugendubel, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-88034-907-X

- ^ Editing and advertising of the "Goldene Eule" , management Willy Sasse: Vom Brühl . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 24, Leipzig, February 25, 1920, p. 24.

- ↑ Gottfried Wilhelm Becker: Painting of Leipzig and its surroundings . Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, 1823, p. 87

- ^ Chronicle of Leipzig. Leipzig-Info.net, accessed on March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Jutta and Rainer Duclaud: Leipzig Guilds , Verlag der Nation, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-373-00370-9 , p. 139 ff.

- ↑ The Israelite Congregation on the side of the Synagoge and Meeting Center Leipzig e. V. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 14, 2009 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Schauplätze Leipziger Psychiatriegeschichte on the website of the Saxon Psychiatry Museum. Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ From the history of the Gewandhaus Orchestra on the GEWANDHAUS ZU LEIPZIG website. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 7, 2009 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Ralf Julke: Time travel on Tuesday: 100 years of Goethe on the square . (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved June 27, 2006 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Illustrirte Zeitung , Leipzig, April 27, 1844, pp. 277 ff

- ↑ a b Jews in Leipzig. A documentation of the exhibition on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the fascist pogrom night in the exhibition center of the Karl Marx University in Leipzig from November 5 to December 17, 1988 (published by the Council of the District of Leipzig, Department of Culture)

- ↑ a b Lienhard Jänsch, Christine Speer: 575 years furriers' guild in Leipzig from 1423 to 1998 . Festschrift on behalf of the furrier guild in Leipzig, 1998

- ↑ Simone Lässig: Jewish ways into the bourgeoisie

- ^ History of A. Lieberoth Bank, Leipzig. In: State Archives Leipzig. Retrieved March 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Dimitri Ch. Totchkoff: Studies on the tobacco trade and skinning, especially in Ochrida (Macedonia) . Inaugural dissertation of the philosophical faculty of the University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg 1900, p. 30

- ^ H. Werner: The furrier art. Publishing house Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, Leipzig 1914, p. 41.

- ↑ Standing Convention . In: Alexander Tuma: Pelzlexikon XXI. Band der Rauchwarenenkunde . Publisher Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1951

- ↑ Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, 2nd improved edition, pp. 279–280

- ↑ Entry on Gloeck's house at Leipzig-Lexikon.de. Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ^ History of the scouts in Leipzig and Saxony on the website of the Bund der scouts and scouts (BdP) e. V. (strain LEO - Leipzig). Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Doris Mundus, Rainer Dorndeck: Furs from Leipzig, furs from Brühl . Sax Verlag, Beucha / Markkleeberg 2015, p. 13, ISBN 978-3-86729-146-0 . Primary source: The British Fur Trade , London, April 1926.

- ↑ a b Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story, Berlin 1941 Volume 3 . Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 41, 100 ( table of contents ).

- ↑ Harold James, Avraham Barkai, Karl Heinz Siber: The German Bank and the "Aryanization". Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Ariowitsch, Julius ( Memento of the original dated February 10, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on the internet portal juden-in-sachsen.de, accessed March 12, 2009

- ↑ Entry on Eitingon, Chaim at leipzig-lexikon.de. Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ^ Article Significant Jewish personalities in Leipzig on the Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk website. Archived from the original on August 26, 2004 ; Retrieved June 22, 2005 .

- ↑ Guide through the Brühl and the Berlin fur industry , Werner Kuhwald Verlag, 7th edition, Leipzig, October 1938, page 179

- ^ Message from the Reich Association of German Tobacco Manufacturers to the Reich Ministry of Economics of October 24, 1933 . Secondary source : Paul Schöps: The fur industry in the 19th and 20th centuries - On the emergence of the global fur industry , chapter company statistics , p. 3 January 10, 1955, original manuscript ( G. & C. Franke collection )

- ↑ Image from William Blye Collection, on A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ RH: Der Brühl - the center of the European tobacco industry . In: Kürschner-Zeitung , Volume 58, Issue 25, September 1, 1941, page 321

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900–1940, attempt at a story, Berlin 1941, volume 1 . Copy of the original manuscript, p. 2

- ↑ Otto Teubel (ed.): Guide through the Brühl and the Berlin fur industry 1950 . Leipzig.

- ↑ Niddastrasse on Commons

- ↑ Bernd Klebach: The Brühl, the Niddastraße, the fur center. Memories of 35 years of the fur industry. Self-published, June 2006

- ^ Birk Engmann: Building for Eternity: Monumental Architecture of the Twentieth Century and Urban Development in Leipzig in the Fifties. Sax-Verlag, Beucha 2006, ISBN 3-934544-81-9 , pp. 158-165.

- ↑ Entry Der Brühl at leipzig-lexikon.de. Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Internet site of the Polish Institute Leipzig 2008

- ↑ Oelßner's Hof is to be sold to Thor's successor. In: Winckelmann-Pelzmarkt , July 30, 1993, Frankfurt (Main)

- ↑ Article about Sachsenplatz on the online travel guide urlaube.info. Retrieved March 12, 2009 .

- ↑ Report by Michael Voss on the ARD sports blog. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 16, 2007 ; Retrieved June 8, 2006 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Forum am Brühl ( Memento of the original dated February 7, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Caleus architects, accessed on February 7, 2017

- ↑ Leipziger Bürger-Portal: Magnet for City is to be created at Brühl. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 21, 2009 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Leipzig Citizens Portal: Project Brühl. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on December 1, 2008 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Page of the ArchitekturRaum e. V. Accessed March 12, 2009 .

- ^ Ceremony in Leipzig. Over 300 guests in the old town hall. In: Winckelmann-Pelzmarkt , edition 1435, September 4, 1998, Frankfurt (Main), p. 1

- ↑ Photo documentation about the demolition of the apartment blocks Brühl Leipzig, Frank Eritt. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 15, 2009 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Theresia Lutz: City representatives provided information about the new refugee accommodation at Brühl , l-iz.de, Leipziger Internet Zeitung, October 28, 2015, accessed October 28, 2015.

- ↑ Excavations at Brühl: A stone house puzzles archaeologists. Leipziger Internet newspaper, accessed on March 19, 2009 .

- ^ Exhibition "Construction site Brühl - Archeology in the smoking area". State Office for Archeology , January 22, 2009, accessed January 30, 2013 .

- ↑ mfi: “Höfe am Brühl” as an homage to the location and architecture. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on January 23, 2009 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ mfi: “Höfe am Brühl” as an homage to the location and architecture. Retrieved December 26, 2009 .

- ↑ Donor for Brühl project jumped: Investor signs anyway . ( Memento from February 28, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: Leipziger Volkszeitung , February 25, 2009:

- ↑ Trade and change on the Brühl: Traders fear building desert in a prime city location. Retrieved March 20, 2009 .

- ↑ Article about the tin can on leipzig-blaugelb.de. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Sophia-Caroline Kosel: The slow disappearance of the GDR on netzeitung.de. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012 ; Retrieved July 6, 2006 .

- ↑ Leipzig gets the tin can back. Aluminum panels have been installed since Friday , LVZ Online, March 3, 2012, accessed on March 4, 2012.

- ↑ Werner Schneider: Article about Wagner's birthplace and the memorial plaque on the Leipzig sheet of music. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on February 13, 2019 ; Retrieved March 12, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Fred Grubel: Write that on a board. Jewish life in the 20th century. Böhlau Verlag Vienna and Cologne, 1998, pp. 25, 90. ISBN 3-205-98871-X

- ^ "H.": A folk piece from Brühl in the Leipzig Comedy House. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 91, Leipzig August 1, 1931, p. 7.

- ^ Letter from son Fred Grubel on the whereabouts of the manuscript. New York 1975

- ^ "H.": Ultimo am Brühl. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 93, Leipzig August 6, 1931, p. 2.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 1. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 170–171 ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

Web links

- Forum for the demolition and re-planning of the Brühl

- Pictures from the Bau Höfe am Brühl Leipzig on bastellen-doku.info

- Pictures of the demolition of the apartment blocks on the Brühl on bastellen-doku.info

- "Pelzstadt Leipzig" in GMD - The magazine from March 20, 2012, 9:15 pm on MDR

Coordinates: 51 ° 20 ′ 33.7 ″ N , 12 ° 22 ′ 42 ″ E