Heinrich Lomer

| Heinrich Lomer

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | one-man business |

| founding | 1835 |

| resolution | 1930 |

| Seat | Leipzig |

| management | Heinrich Lomer; different shareholders |

| Branch | Tobacco shops, fur retail |

The tobacco merchant Johann Heinrich Lomer (born March 18, 1812 in Lübeck , † August 29, 1875 in Leipzig ) founded a fur wholesaler under the Heinrich Lomer company in Breslau in 1835 , which he moved to Leipzig in 1844 and was able to expand significantly. It lasted until bankruptcy in 1930, the time of a major slump in sales for the industry during the Great Depression. With the book “Der Rauchwaaren-Handel”, Lomer created the first comprehensive work on the world fur trade.

Company history

Heinrich Lomer was a son of the Lübeck colored feeder Gerhard Diedrich Lomer (1778–1846), who had a “warehouse of American and Russian fur goods” there on Breite Straße .

The Heinrich Lomer company was at times considered the oldest Leipzig wholesaler in the fur industry . While Leipzig was already of great importance in the Middle Ages as a market and transshipment point for various goods due to its central location, this was almost completely lost at the beginning of the 19th century for the once also considerable fur trade. After the continental blockade imposed by Napoleon was ended in 1815, only two long-established tobacco companies remained. Within just ten years, the situation largely normalized and the Leipzig tobacco companies regained their connection to world trade. Like other newly formed fur companies, Lomer was successful, not least because of the freedom of trade introduced in the 1860s. Leipzig with its companies around the Brühl rose to the leading European fur city in the following decades, especially because of its quality in fur dressing and finishing . When around 1900 with industrialization, the introduction of the fur sewing machine and a fashion in which the fur was worn with the hair on the outside, the demand for furs increased very quickly, the now established and financially strong company Lomer was one of the companies that benefited greatly from this upswing.

As early as 1862 an author wrote for the family magazine Die Gartenlaube impressed, although he found the exterior of the company building, which was located in the middle of other, likewise elaborately designed house facades, to be "inconspicuous":

“This entire, constantly renewing store is the property of Herr Lomer, who occupies a prominent position in the Leipzig fur business, the main part of which rests in only three or four hands. And the total turnover in smoked goods in Leipzig is over six million thalers a year.

Just as the stranger, who wanders the narrow streets of inner Leipzig outside of the time of the Mass, may seldom form an idea of the riches of these gloomy, pointed-gabled houses, so may he also of an inconspicuous building in Brühl, which the simple company "Heinrich Lomer ”wears, standing without having a clue of the treasures that are revealed to the knowledgeable eye and that even queens can get a faster heartbeat out of it. He stands in front of one of the most important of those few wholesalers in Leipzig, which unite the main center point of the entire fur trade in the world, and to whom it is allowed to take a look through their rooms under the direction of the friendly owner, ideas open up In spite of all respect for Leipzig's general trade, he would hardly have believed in earlier.

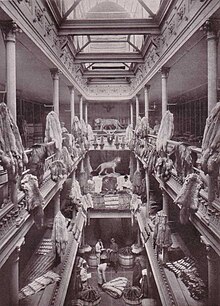

Let's step into the huge, four-story warehouse, which receives all of its light through the roof, and take a tour that will give us the quickest idea of the grandeur of the establishment. Whether the usable types of fur of all stretches of earth are gathered here in large or small stocks, there is such a systematic order and clarity that we can hardly err in our considerations.

In addition to the local business with its multitude of preparations and scattered workers, the latter also owns a commandite and preparation establishment in London; his fur purchases are made either directly from the United States and Russia, or through the Hudson Bay Company in British America, which had received the monopoly of the entire fur trade there from the British government. However, it may speak for the high boom in local fur-making that America and Russia, which deliver the bulk of the raw material here, get it from here in the processed state. "

The author of the gazebo describes the bulk of the existing types of fur of martens, polecats, otters, badgers, Dutch cat , swan and goose furs and French rabbit skins , astrakhan fur , as well as "huge drums" with about 100,000 Rotfuchsfellen . The native animals alone sell more than two million thalers of skins in Leipzig every year.

The precious sables came from Russia, for “only the trifle of 100 Thalers each; next to it snow-white ermine raw and already worked ”and about 1 ½ million skins of the gray Siberian squirrel. It is mentioned that in Weißenfels and Naumburg there was an industry of their own, in which women from the bourgeoisie sewed the false skins together into semi-finished fur products. The fur tablets were then resold to fur manufacturers around the world via establishments like Heinrich Lomer's.

The fur trimmers around Leipzig were also valued worldwide for their quality work. The skins of Angora goats only came to Leipzig to be trimmed here and to be exported back to Russia by trading houses. This also applies to the astrakhan and Persian skins , for which the plants in Markranstädt had a special reputation as tanners, but also especially for dyeing black. They went via Leipzig, especially to Hungary for “men of the National Party ” and to Paris.

Other items mentioned in the article and waiting for customers at Lomer were around 100,000 beaver pelts and 400,000 muskrats from North America, whose wool hair was still used to make felts for hat production in the first few years of the company's existence, but now, with pulled out guard hair, was mainly made into men's collars . There were also wolf skins of all colors, raccoons, black and gray bears, polar bears, wolverines and skunkers. Foxes came in great variety, white, blue, and cross foxes ; Silver foxes at 125 thalers a piece, and at that time "the longing of every real woman of fashion: black fox up to 250 thalers the fur". With the first seal jacket made of black-dyed fur seal skins, from which the upper hair had also been removed, the modern fur fashion began, in which the fur was not only worn in the trimmings and as a collar with the hair on the outside. The sea otter was not yet protected, there were only a few copies for 300 to 350 thalers each. These skins were mainly used as collars on men's furs , the incredibly high price would probably have led to the extinction of the big otters without the protective measures. There was also chinchilla from Chile, but the specialist for this was Richard Gloeck , which is also based in Brühl in Leipzig . In addition, however, cheap goods such as lamb or goat skins were traded in large bales or stacked goods in barrels.

Attempts were made again and again, mostly with little success, to introduce the tobacco sales for Europe in London also in Leipzig. Around 1878 the companies Heinrich Lomer and G. Gaudig & Blum jointly founded the auction house Lomer, Dodel & Co. Their auctions were also discontinued after a short time.

Heinrich Lomer's sons Emil and Gustav joined the management of the company in October 1865 and continued to run it after the senior's death in 1875. In February 1893 the company went to Gilbert Lomer and Karl Lentsch. Lentsch had been working here since 1875. On February 1, 1904, Moritz Becker became a partner. After Gilbert Lomer's death, Karl Lentsch and Moritz Becker were the owners of the company.

In some of the western cities of the world that are important for the fur trade, the company maintained commercial agencies with their own warehouses. In 1913 these were Berlin, Brussels, London, Milan, Paris and New York. The subsidiary Lomer & Co. , which resided in the same office building on the Brühl, was responsible for the distribution of the small lambskin varieties Astrakhan , Breitschwanz and Persianer .

Wholesaling was the actual core business of the company, but the Lomer company still had a retail store in the front building, as was common practice with many wholesalers, but aroused considerable displeasure among furrier customers, especially the Leipzig fur retail trade. In 1914, the company therefore committed itself to its furrier customers, together with other tobacco merchants, not to sell at least any furs to private customers.

The crisis year 1930 brought the largest number of bankruptcies that the fur industry has ever seen. Nevertheless, it was a great surprise that the largest and oldest company on the Brühl was also affected: In March 1930, "the Heinrich Lomer tobacco shop, Leipzig, Brühl 42, with about 2 to 2½ million marks in liabilities, stopped making payments". “The creditors' committee was composed of the Leipzig companies: Einschlag (J. Ariowitsch), Dr. Nauen ( Theodor Thorer ), Hirsch Goldberg, Dr. Rentsch und Silberkweit (Ch. Eitingon AG) ”“ At the creditors' meeting, liabilities of RM 1,524,000. and assets of 816,900 RM. which, however, will be difficult to implement. The creditors advocated a liquidation settlement, according to which 35% should be paid out in full and any remaining 60% should go to the creditors and 40% to the debtors. "

The Pelzkontorhaus, called the "Pelzkirche"

A building that attracted much attention was the office building of the Lomer company, Brühl No. 42, called the “fur church” or even “fur cathedral” by the people of Leipzig because of its sacred appearance. It was a modern commercial building, and the historicizing facade also matched the style of the time.

Before Heinrich Lomer had his warehouse built in the courtyard of Brühl 42 in 1857, the property was built on with a number of small, nested houses, some of which on the first and second floors served as defeat for merchants. By 1800 the property belonged to a member of the fur industry, a master furrier named Mehlgart. In a back building of the complex was the restaurant "Zum Weißen Roß", which was mentioned in the 16th century.

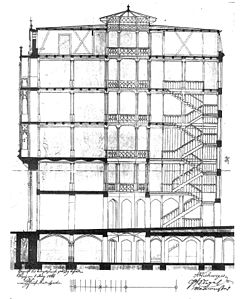

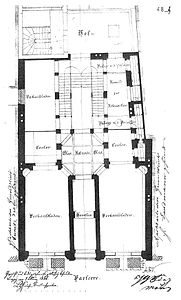

- Over an elongated plot of land enclosed by ancillary buildings, two buildings were erected on each right-angled base, which were separated from one another by a small courtyard and the staircase of the rear building. The floors of the front building, which also had a basement and attic, were accessed by a staircase at the rear. A centrally located, open entrance led from the street into a rotunda, which was illuminated with daylight through openings in the ceiling and glazed in the roof. From there there was access to the adjoining rooms on the ground floor, the courtyard and the staircase on the back. A two-armed staircase in the central axis of the building directed business traffic to the upper floors, another curved side staircase on the eastern side wall served the staff and reached under the roof. Two shops and technical rooms were housed on the ground floor, the upper floors were used as a tobacco store and workrooms. So that the light could reach the rooms unhindered through the rotunda and the large windows, there were no partition walls on the floors. The ceilings were supported by the side walls and iron supports. The three-axis street facade was designed in a striking neo-Gothic style. The narrow central axis connected the entrance portal, bay window and the window gable adorned with fial decorations in the roof. The three-storey bay window was fitted with triple windows and Gothic ornamentation and was from a window gable and pinnacles considered. The four unusually large, pointed arched windows on the side axes dominated the appearance of the building. They were divided into three lanes and interrupted horizontally by beams in the area of the ceilings. The two lower windows combine the ground floor and the mezzanine to form a shop area, while the upper windows, in keeping with the bay window, combined the remaining three upper floors to form a warehouse and business area. The low, seven-axis attic was set off as a living area with a series of triangular window and facing gables. The wall surfaces of the facade were largely reduced to their supports. Bundle pillars, tracery in the arched fields and Gothic architectural decorations enlivened the appearance of the front.

- The five-storey rear building with basement and attic was illuminated through a long atrium with a barrel-shaped glass-iron roof down to the ground floor. Rows of cast iron Corinthian columns along the galleries supported the ceilings. The loads were absorbed in the basement by a grid of sturdy metal columns with beams. The narrow, single-axis courtyard facade consisted of two coupled arched windows up to the third floor, which were combined by an arch above. It was divided into a square ground floor plinth, which accommodated the two round-arched portals and ended with an ornamented cornice, into a central zone, which was divided by two windowsill cornices and a roof zone, which was introduced by a cornice. Wall pillars framed the windows on the upper floors. The low attic had three small, closely arranged arched windows.

- The courtyard area was further reduced by the new building from 1857. There was no passage to the neighboring property behind. The exhibition and sorting rooms of the tobacco shops needed a maximum of daylight so that the fur quality could be reliably assessed. To solve the lighting problem, an elongated atrium was cut into the central axis of the building. This was covered with a barrel-shaped glass-iron construction. All five floors, the vaulted cellar and the attic were used as storage and sales rooms. On the contemporary view of his warehouse one can see fine furs in large and small bundles. The parapets of the galleries were splendidly decorated with valuable sables, foxes or minks. The goods were transported to the upper rooms by an elevator in the courtyard. The expedition office where the skins were unpacked and packed was on the first floor. There was also a shop where foreign middlemen, garment makers, but certainly also local furriers were received, who bought here directly and cheaply. In this store, finished fur clothing was sold directly to the end consumer. In 1857, when the new defeat occurred in the courtyard, Lomer expanded his business and had the passage into the courtyard expanded to meet the increased demands of traffic. Soon the street building no longer met the expectations of the merchants and so it was demolished in 1866 and replaced a year later by a spacious new building that met the requirements of modern commercial buildings. In the process, business premises were added, as the upper floors were no longer rented for residential purposes. If you didn't need these new workrooms yourself, as happened later, it was more profitable to rent them out for commercial purposes than for apartments. The renowned architecture professor August Friedrich Viehweger was entrusted with the design . The walls, largely dissolved as glass surfaces, which only left the supporting pillars, characterized the building as a commercial building. Similar to the echoes of Gothic cathedral architecture in some department store buildings of the time, Viehweger chose traditional sacred architecture as a dignified framework for the staging of his building, which was popularly known as the “fur church”. In the cathedral gothic, as in the commercial building with its largest possible shop windows on the ground floor, the walls were largely reduced to their supports in favor of the largest possible windows. The sacred facade, the decor and the bundles of columns inside as well as the light-flooded courtyards and stairs satisfied the increasing need for representation of the time in the ensemble.

- The actual house name of Brühl 22 was "Gute Quelle". In 1867 a restoration called "Gute Quelle" moved into the cellar vaults of the front building, which were illuminated by light shafts facing the street and glass elements in the ground floor ceiling of the rotunda. Further renovation work continued in the rear hall in 1869: a Singspieltheater with a stage, parquet and tier was set up on the lower two floors. A double-shell glass roof in the atrium between the first and second floors separated the fur defeat from the thriving entertainment business. In 1878, the company Joseph Finkelstein & Co. held one of the first Leipzig tobacco goods auctions with Russian goods as a tenant in the hall. However, the auctions were not very successful and so they were abandoned a few years later. In 1921 the restaurant was called "Blaue Maus" with a newly designed hall under the operator Mielke. In the 1920s and 1930s, continued under Max Schütze as “Zum Platz'l”, bowling alleys were even operated in the basement. Until it was destroyed in the Second World War , the buildings were still used as a tobacco shop and restaurant.

- - According to J ENS S CHUBERT : "The fur trade houses in downtown Leipzig"

- Architect's plans for the Heinrich Lomer smoking goods defeat

Works

- commons: Category: The smoking goods trade . History, operation and commodity knowledge. Leipzig 1864

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Baptismal register of the Jakobikirche (Lübeck) 1812, accessed via ancestry.com on February 1, 2019; Emil Ferdinand Fehling : From my life. Memories and documents. Otto Quitzow Verlag, 1929 ( digitized version ), p. 31.

- ^ Cultural elites in Leipzig . P. 97. In: Thomas Höpel: Culture and urban culture in Leipzig and Lyon (18th-20th century) . Leipziger Universitätsverlag 2004. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ↑ Fur Trade Review 39 (1910), p. 77

- ^ Entry in the Lübeck address books, quoted from Björn R. Kommer: Steuer in Lübeck in the year 1840. In: Zeitschrift für Lübeckische Geschichte 70 (1990), pp. 175–191, here p. 186

- ^ A b Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 3. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 28, 30 ( → table of contents ).

- ↑ a b c IPA - international fur exhibition, international hunting exhibition Leipzig 1930 - official catalog. Pp. 242, 252.

- ^ A b c d e f g h i Jens Schubert: The fur trade houses in downtown Leipzig . Mag.work, Leipzig 2003.

- ↑ Without the author's name: A Leipzig wholesaler . In: The Gazebo . 1962. p. 580.

- ↑ A Leipzig wholesaler . In: The Gazebo . 1962, p. 582.

- ↑ Fur Trade Review 39 (1910), p. 77

- ↑ tobacco prices index Heinrich Lomer, Leipzig, 1913-1914 . P. 2.

- ↑ tobacco prices index Heinrich Lomer, Leipzig, 1913-1914 . Pp. 28-29.

- ^ Association of German furriers. Concerns the sale of skins to private individuals . In: Kürschner-Zeitung , Verlag Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, No. 9, April 26, 1914.

- ↑ The wave of bankruptcies . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 53, Leipzig, March 22, 1930, p. 7.

- ^ In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 44; April 12, 1930, p. 7.

- ↑ In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 53, May 3, 1930, p. 5.

- ↑ Jens Schubert. See StadtAL, Bauakten, 3814 (Brühl 42) fol. 8 f.

- ↑ Jens Schubert. StadtAL, Bauakten, 3814 (Brühl 42) fol. 1-6.

- ↑ Jens Schubert. Secondary source: Ernst Müller: The house names of old Leipzig . From 15.-20. Century, with sources and historical explanations. Leipzig 1931, pp. 6, 10 f.

- ↑ Jens Schubert. See StadtAL, Bauakten, 3814 (Brühl 42) fol. 45-48.

- ↑ Jens Schubert. See StadtAL, Bauakten, 3814 (Brühl 42) fol. 22nd

- ↑ Jens Schubert. Secondary source: Andreas Lehne, Gerhard MisslL, Edith Hann: Wiener Warenhäuser . 1865-1914, Vienna 1990, p. 4.

- ^ A b Ulla Heise: A guest in old Leipzig . Hugendubel, Munich 1996, p. 51, ISBN 3-88034-907-X .

- ↑ Jens Schubert. Secondary source Fritz Pabst: The smoking goods trade . Dissertation Leipzig 1902. pp. 97–100, → table of contents .

- ↑ Jens Schubert. See StadtAL, Bauakten, 1262 and 3814 (Brühl 42).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lomer, Heinrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German smokers' merchant |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 18, 1812 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lübeck |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 29, 1875 |

| Place of death | Leipzig |