Otter skin

Otter pelts are considered to be the most durable of the furs, and they are at the top of the shelf life tables for furs . They are differentiated in the tobacco trade according to their origin. Originally at home all over the world, the otter has now become rare in most areas. Except in the polar regions, it is only absent in Australia and Polynesia. The trade has almost completely come to a standstill, essentially only North American otter skins are in trade, most of the traditions are subject to the trade restrictions or absolute trade bans of the Washington Convention on the Protection of Species .

The fur trade traditionally calls European otters land otters.

Among the otters you can find the largest representatives of the martens ( giant otters and sea otters ) with a head body length of up to about one meter .

General

As with all martens, the males are about a quarter larger than the females. Their fur is either evenly brown-gray, sometimes lightly speckled and often a little lighter on the "collar" and / or on the stomach. With more than 1,000 hairs per mm², they have one of the densest skins in the animal kingdom. Due to the structure of the fur - long fur protects the thick, soft undercoat - you can keep an insulating layer of air around your body even when you stay in the water for a long time. Because of this dense, stable coat, the fur has long been said to have the greatest durability of all types of fur. The hair change takes place, as is usually the case with animals that live a lot in water, very slowly and not as a two-time seasonal change of coat . At least with the sea otter, the hardening is stronger in summer, so that the winter fur is denser.

The durability coefficient for otter fur is given as 90 to 100 percent. When fur animals are divided into the hair fineness classes silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the sea otter hair is classified as silky and the otter hair as fine.

Otter was mainly used for coats and jackets and for trimmings on fine men's " furs ". As early as 1884 , in the reputable Roman magazine La Tribuna, D'Annunzio described the first long otter coats adorned with beaver, apparently some of the earliest modern fur garments with the hair facing outwards. Apart from the fact that all species with the exception of Lutra canadiensis are now protected by trade bans under the Washington Convention on Endangered Species (maximum protection for South American otters since June 20, 1976), the formerly so coveted skins are at least found in the favor of the current fashion of light materials hardly any attention in warmer countries. The IUCN classifies the otter overall as "low risk". However, the population trend is decreasing.

Unless otherwise stated, the skins of the individual origins are delivered to the fur trimmer uncut, peeled off round, with the hair facing outwards, partly inwards.

Around 1900 the skins of the otter shrew (West Africa, Congo and Angola) were in trade as baby otters . However, the occurrence is limited and the delivery was therefore very small. The mink fur was once falsely traded as an otter, under the name of the marsh otter .

Otter

Different species around the world are referred to as otters , often with considerable differences in size, color and hair structure. In most areas they have become rare: Not only did the fishermen chase them - the skins were also in great demand everywhere. The otter has hardly any natural enemies, and apart from hunting, the increasing displacement through cultivation was decisive for the decline in the population. In addition, there was a decrease in fish stocks due to the pollution of rivers and lakes.

The head body length is up to 110 centimeters, the hairy tail is 30 to 55 centimeters long. There are webbed feet on the front and rear paws. The coat is predominantly brown in all shades, sometimes blue-black to almost black, bluish to brownish, grayish to reddish, occasionally also to gray-brown. It is seldom spotted gray-white or pure white. The ventral side is thicker in the hair and colored lighter (dark to ash gray). The throat patch typical of many species of marten is yellowish-white to reddish. The front neck and the sides of the head are whitish gray-brown. The undercoat is light gray to yellow-brownish, sometimes with a white background (the dark Indian and USA varieties), also salmon-colored (Brazil).

The hairs on the back of northern otters have the following average lengths (in millimeters): guide hairs 24.2, guard hairs 18.4 and woolen hairs 14.6. The hair on the stomach is a little shorter, but thicker. There are around 35,000 hairs on 1 square centimeter of the back and around 50,000 hairs on the stomach. There are 120 wool hairs on the abdomen and 155 on the back.

The leather is light to heavy.

Europe and Asian parts of Russia (Eurasian otter)

All otters are in Appendix II of the Washington Convention on the Protection of Species , some species, such as the Eurasian otter , the South American otter and others even in Appendix I (absolute trade ban).

| Sizes | sorts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | 90 to 110 cm | I. | full-haired | |

| medium | 70 to 90 cm | II | less full-haired | |

| Small | up to 70 cm | III | half-haired |

origin

- Norway and Sweden supplied the best Eurasian otter skins, with a thick, dark gray undercoat and fine, soft, dark brown upper hair. In terms of quality and color, the Scandinavian otters, especially the Laplanders , are almost the same as the Alaskan otters.

- Switzerland, southern and central Germany, England : some of the skins are beautiful in color. Skins from Austria, France and the Balkans are smaller. The best German, smoking and dark, skins used to come from Bavaria. Czech varieties are also smoke and dark.

- Greece , the skins are of very low quality (“stuffy”), the Macedonians are better .

-

Russia, Siberia : A distinction is made here between

- European otters from western, northern, central and southern Russia, and

- Siberian , of which the lighter ones, with a yellowish tone (South Siberian) are called Caucasian , while the dark, bluish skins were traded as Siberian.

The skins of very young otters were traded as milk otters .

North America

The occurrence of the North American otters , also Canadian otters , for a long time mainly known in the trade as Virginian otters , is Alaska and Labrador up to the southern states of the USA. It occurs in 45 US states and in all Canadian provinces, except on the Prince Edward Islands. The best varieties are in the northeast (especially silky and dense). Some dark varieties have a light to white-ground undercoat. If these skins have stocky hair, they were plucked and dyed black (seal-colored) in the past, as were light and discolored skins. The western origins are weaker in quality and color as well as coarser and thinner in the undercoat. Only the Alaskan otters are finer ( medium silky ). In the south the quality is usually lower.

The coat color ranges from light brown to bluish black. Furs from the USA, especially from the north, are often dark in color, the western varieties are brown. Blue-brown furs also come from Alaska. The coat of the Florida otter is particularly dense, brown to almost black-brown. The coat sizes vary considerably.

The northeastern ones are mostly thin in leather (light leather), central ones (USA) and western ones are a little heavier. The leather of the Central and Eastern Canadian varieties is very clean, cleaned with a pumice stone . Above all, it is free from carrion, while the leather of the other American varieties is often heavily contaminated with fat, especially those from Carolina and Florida.

In 1960 it is described that the North American otter skins often come out of the fur trim in the awn ("scorched") crooked . The darker and finer-haired a lot was, the more crooked-pointed pelts there were. The cause was assumed to be improper, too warm drying of the raw skins, as the finishers ruled out crooked pelts with proper dressing. The tendency to crooked hair can already be seen in the raw state, especially when the hind paws are crooked. If the fur on the hind paws is crooked, it is usually also the back.

The fur sizes between the varieties are several times different.

Hudson's Bay Company and Annings LTD., London sort as follows:

- Origin : LS ( Upper Lake ) & MR ( Moose River ), Alaska, USA, Scandinavia

- Sizes : xx large (over 40 inch), x large (38 to 40 inch), large (36 to 38 inch), medium large (34 to 36 inch), medium (32 to 34 inch), small (under 32 inch)

- Types : dark (dark), medium (medium), pale (light)

The skins are delivered with the hair turned inwards.

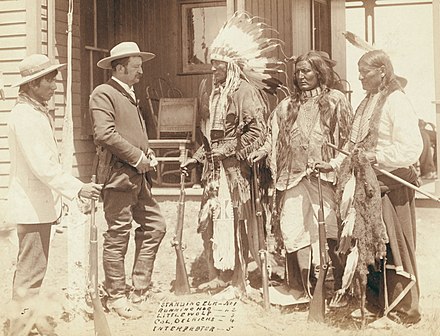

Quiver made from an otter skin of the Yahi Indian Ishi

- Northeastern

Full in the hair (smoke), sometimes almost silky, stocky; dark to almost black; light-leather. The quality is generally very good.

- 1. Eskimo Bay (EB)

- Very fine; dark to almost black (bluish). Finest quality.

- 2. Fort George (FG)

- Very fine; dark to almost black (bluish).

- 3. East Maine (EM)

- Very fine; almost black (bluish).

- 4. Maine River (M)

- Very fine; dark brown.

- 5. Labrador (Lab)

- Very fine; very dark.

- 6. Newfoundland (NFL)

- Very fine; dark brown.

- 7. York Fort (YF)

- Very fine; dark brown to light brown.

- 1-3 large - 4-7 slightly smaller

- Eastern

- Medium to large in size; coarser, dense; brighter. Mostly heavier leather.

- 8. Halifax (New Scotland)

- Large, dark brownish; strong hair.

- 9. East Coast (USA): Maryland, Kentucky

- Dark brownish.

- 10. North Carolina, South Carolina

- Dark brownish. Better grades from North Carolina.

- Southern states: Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi

- Smaller; dark brownish, partly less good in color (including Alabama); weaker in the undercoat; heavy-leather.

- 12. Georgia (East), Florida

- Greater; coarser, thinner in the hair (thinning); reddish to brown; greasy in the leather.

- Western and Central

- Large to very large; coarser, weaker to dense; brighter; heavier in the leather.

- 13. Alaska

- The largest variety; tight; medium-colored to dark. Lighter skins are particularly suitable for plucking.

- 14.Western Canada (North Western)

- Large; weak undercoat; light to dark.

- 15. British Columbia

- Large; very brown; heavy-leather.

- 16. California

- Very large; light to medium colored.

- 17.Western Central States (Wyoming to Mexico and Sonora)

- Very large; bright; "Gnarled" leather.

Middle and South America

South American otters (four species) are, with the exception of the giant otter , much smaller than North American ones ; The length, thickness and density of the hair are not equivalent to those in North America. The hair is much flatter, mostly flat and coarser. The undercoat is not as fine and considerably shorter and flatter than that of the North American ones.

In addition to the giant otter, the coastal otter ("sea otter") , the South American otter and the southern river otter live in South America .

The southern varieties are best. Sometimes they almost resemble arctic traditions. The skins of temperate zones are of lower quality. Furs from the Amazon region are good in color, dark with dark flanks. On the other hand, otters from Paraguay, Bolivia and others are very different in color, often they have orange flanks. The pelts of tropical occurrences are of the lowest quality, so that they " hardly deserve the name fur fur ."

- south

- The best, particularly smoky varieties are those from Tierra del Fuego , southern Chile, Patagonia , Uruguay and southern Brazil. You are fully in your hair (“good smoke”); predominantly medium to dark brown.

- Southeast (Argentina)

- The upper hair is close fitting, moderately long, shiny. The undercoat is dense; dark brown.

- Furs coming from Argentina were cleaned in the leather and stretched very carefully in a rectangular shape , the trade name was Washbacks . In Buenos Aires otter skins were traded as Lobo (del Rio), in Punta Arenas the best skins were traded as Nutrias Maghellanes (nutria means otter in Spanish). When sold by the London tobacco shop, the origins were no longer specified, they were consistently traded on as South American otters .

- West (Ecuador south)

- The skins are smaller than Argentine varieties. The best come from Chile (Puerto Monti and Chilos).

- Tropics

- Very low quality, gross. Was used as leather.

- Giant otter, ariranha otter

The fur of the giant otter was sold as Lontra or Ariranha . The giant otter forms a specialty with its short-haired and fine fur, despite its considerable size. It has a head body length of 100 to 150 centimeters, in addition the tail comes with about 70 centimeters. It lives in the tropical regions, on rivers in Venezuela, Guayana, Uruguay and Argentina. The hair, at least on the commercially available hides, was flat, short-awned, and remarkably silky; the undercoat tight. The color is light brown-yellow to chocolate-brown, the lower neck has elongated whitish spots reaching to the chest.

Deviating from this, Schöps wrote in 1960 that the Ariranha otter skins were not considered suitable for processing fur because of their coarse hair. The hair is said to be short, coarse to hard, and poorly developed; seal-like. The trade, especially the London tobacco market, was therefore only supplied with smaller quantities that could still be used for fur purposes. Depending on their origin, they were traded as the Amazon, Orinocos, etc. Only the Amazon were suitable for coats, the rest was made into leather.

All otters in South America are now under the full protection of the Washington Convention on Endangered Species .

Africa

West Africa, Central Africa (Kongootter), South Africa (Rhodesia Otter)

The spotted neck otter lives in Africa , of which only the Congo otter living in the Congo and the South African Rhodesia otter were traded in Europe.

The large varieties are 90 to 100 centimeters long and 60 centimeters wide, the smallest skins with a predominantly wide tension are 25 to 30 centimeters square, with normal stretching they are 40 to 50 centimeters in length. The delivery was once significant. The fur is coarse, often stuffy, and sometimes well stocked. The undercoat is very weak to stunted. The color ranges from medium brown to dark brown (chestnut), sometimes with white dots, shiny metallic (bluish-gray), the undercoat is yellow-brown. The throat patch is often fiery orange in color.

The capotter is native to all of Africa south of the Sahara from Abyssinia. Unlike the otters with their “nail-like” claws, the animals belonging to the genus of the finger otter have only small or no claws at all, the webbed toes are only slightly pronounced. They reach a head body length of 95 to 100 centimeters, the tail is about 55 centimeters long. The coat is dull brown with isolated whitish markings on the cheek, throat and chest.

The pelts of the Congo and Cape otters were stretched into a rectangular shape while they were drying; the expansion at the nail points made them resemble a toothed postage stamp. These two types of otters do not achieve the coat quality of the other origins from Africa and Madagascar. The hair is flatter, also compared to the Indian and East Asian varieties.

The skins of the Rhodesia otter are larger than those of the capotter; However, the quality and color are less appealing.

The finishing process sometimes resulted in 30 percent crooked (scorched) skins. Large (regular) and medium-sized varieties were mainly made undyed and unplucked to create collars, the good varieties of the Congo otter also made into coats. The sub-varieties mostly went to China. Very large skins were often tanned into leather because of their poor quality.

Some populations of the third species, the small-clawed otter , are listed in Appendix I of the Washington Convention on Endangered Species (absolute trade ban). In 1988 it was said of the Congo otter that no fur had been delivered for a long time. Even the skins of the Cape otters came into the trade only very sporadically around 1988.

East Africa

The skins from East Africa correspond to the average African quality. However, there were also good hides; also black-brown skins in small numbers. The delivery is open, mostly square, larger heads were stretched rectangular.

Asia

The occurrence of the Eurasian otter in Asia extends to India, China, Korea and Japan. The Indian otters also live in Asia , from Iraq to Indochina and Sumatra, and the hair-nosed viper in Thailand, Sumatra, Borneo, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Some of the otter skins that occur in Asia come on the market as Indian otters , Burma otters and, because of their deep dark color with a dark belly, as black otters . Burmese otters are particularly dark (technically "blue"). At times, large quantities of Chinese otters came onto the world market, because their flat hair makes them less suitable for plucking. Another major supplier was Japan.

Since the sizes as well as the coloration can differ considerably within the tradition, the expert can often only recognize the area of origin by the treatment of the skins. Some of them are stretched uncut in the shape of a long triangle (tapering towards the head, downwards in width), some are open, broadly stretched.

China, Korea

The otter pelts from northern Manchuria and Korea have strong hairs, the southern and central origins are flat. The color varies from dark brown to chocolate to yellowish brown. The undercoat is short, dense, yellowish gray. The size classification is: small 40 to 45 centimeters, medium 55 to 60 centimeters, large 80 to 100 centimeters.

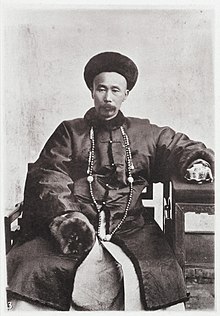

The attack in China was once considerable, particularly in Chekiang ( Zhejiang ) and Hupeh ( Hubei ). Most of the skins were used in China itself, for hats and fur lining, plucked otters mainly undyed. For the traditional, typical clothing of Tibetan nomads, the Lokbar , the lower edge of which is covered with otter, gazelle or other skins, otter skins were offered on Chinese markets around the year 2000.

South Asia (India)

South Asian grades are small to medium in size; short-haired, coarse; light brown to grayish; the undercoat is weak. The deliveries are pointed at the top and wide at the bottom. So-called white otters also come from India , with the belly side being pure white and the back brown with scattered light gray hair.

Central Asia ( Himalaya )

The very small seizure corresponded to the South Asian varieties, but with coarser hair.

West Asia (Baghdadotter)

The pelts delivered from Iran come in the form of a bag (closed at the base of the tail) with the hair facing outwards. The Baghdad otters are gray-brown; coarser and of lower quality in the hair, especially in the lower hair. They are very similar to the Greek otter. It is delivered cut open, narrower in the head and wider in the torso.

Japan

Japanese varieties are flat in the hair; medium brown. Compared to the Chinese, they are larger and finer, compared to Europeans, finer and denser. The attack was once considerable, the delivery was open (tense). They were mostly plucked in Japan and made into collars and hats in the country.

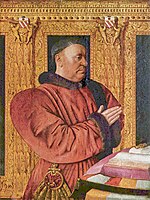

History, processing

Otter collar and cuffs (Portrait of Guillaume Juvénal des Ursins , c. 1460-1465)

Bonifatius (around 673; † 754 or 755), the English Benedictine monk, sent an otter robe to his homeland during his missionary work in Germany. The Bishop of Winchester also bequeathed such a gift to the Abbot of Sull [?] In 704.

In numerous national and national costumes, where fur was used as a decorative accessory, the otter skin was used. In Bavaria women's hats were made from natural furs (undyed and not plucked): “ (the best otter skins are used for this, with gold embroidered inlays, so that they often cost 30 and more guilders). Individual smokers in Munich often buy several thousand pieces of otter skins at once ”(1864). The German hussar officers wore headgear made from natural otters, the Kalpaks .

At the beginning of 1900, the use of otter skins as the trimming of furs and winter clothes, fur collars, hats and hat trimmings is mentioned. On Kamchatka, otter skins were used to pack the more valuable sable skins . It was justified with the fact that because this aquatic animal soaks up all moisture and moisture, the sable fur is better preserved in color .

Up until the First World War , when the war ended in 1918, otters were rated the highest in Central Europe compared to all other native fur species. In addition to the beaver fur , he was also wearing the fur, which was preferred for furs as a collar trim or as an inner lining by the upscale men of the upper class. The classic uses for otter fur were men's hats, men's trimmings, trimmings, but also jackets and coats. For the latter, the flatter qualities were preferred. After the Second World War, women's furs were made from otters.

The fishing of the American otter for fur began in the late 16th century, at a time when beaver fur was of far greater interest . The best American otter skins have been called mirror otters because of their beautiful sheen. In the American and Northern European varieties with dense hairs, the guard hair was often removed by plucking, in the time of seal fashion (until the end of the 1930s) it was even predominantly, a type of refinement that was also applied to other types of fur at the end of the 20th century, such as mink (" Samtnerz ”), became very fashionable again. The original name for plucked otters was Sealotter , named after the fur seal's fur, which was then more valuable, plucked fur . The flatter and lighter varieties were always unplucked, often dyed and processed. Around 1900, Central Asia was an important buyer for these qualities, especially the Kyrgyz there . In particular, the southern European and Chinese otters, among others, were eligible for this. Some of the Chinese otter skins went to Korea before 1900, where they were used a lot for collar trimmings and cuffs, preferably the light peritoneum. At that time there was still so much skins in Europe that they were often exported to China.

In some North American Indian tribes, the men wrapped otter skin around their braids as jewelry.

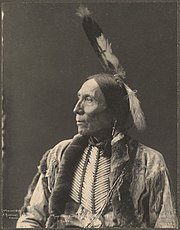

- Otter as a hairstyle of the North American natives

Ute Chief Buckskin Charlie (1901/02)

The hard-wearing otter fur, despite its considerable weight in some varieties, has always been considered particularly desirable, later the fur of the sea otter in particular. As a result of the milled finishing , the types used for coats and jackets were often very heavy-leather . Today with special machines a cloth-like soft leather is achieved by even thin cutting. However, according to the fur trimmers, the pelts are often poorly pretreated, damage that is often not noticeable in the raw fur , resulting in high losses. Many origins have an undercoat that is unfavorable in color, which is largely leveled out with modern finishing methods. Even in earlier times, otter skins were dyed from the hair side with the brush ("blinded"), as can be seen in old recipe books. Today procedures are used which correspond to the "re-inforcing" of mink fur.

As with all types of fur, the pieces of fur that fall off are also used with otter fur if there is a sufficient amount . In particular, the sides of the hide, which are thinner in leather and hair density, are combined to form so-called bodies. The main place for bodywork in Europe has always been the Greek Kastoria and the smaller, nearby town of Siatista . As a semi-finished fur product , the fur panels are exported for final processing, mostly for use as lining for winter textile clothing.

After 1940, most otter skins were processed in a natural color, lighter and brown-colored ones were mostly darkened. Lesser and crooked ones are plucked when there is a corresponding demand and refined into seal or, according to today's linguistic usage in the fur industry, into velvet otters. However, only the land otter and the North American otter are suitable for plucking, the weaker varieties from Africa and South America have too little undercoat.

After the Second World War, skipping became the norm for almost all types of fur suitable for this , a working technique that had become economically feasible with the invention of the fur sewing machine before 1900. Here, the fur is cut into narrow, V- or A-shaped strips (usually 7 to 8 millimeters wide in the case of otters) and sewn together so that a, now narrower, fur is created in the desired length. Since the otter was also used as a jacket or coat found its way into women's fashion at the time, the otter skins were also left out accordingly, now mostly unplucked.

In 1965 the fur consumption for an otter coat was specified (so-called coat "body"):

- Otter = 10 to 16 skins

- Arianhaotter = 4 to 5 pelts.

A board with a length of 112 centimeters and an average width of 150 centimeters and an additional sleeve section was used as the basis. This corresponds roughly to a fur material for a slightly exhibited coat of clothing size 46 from 2014. The maximum and minimum fur numbers can result from the different sizes of the sexes of the animals, the age groups and their origin. Depending on the type of fur, the three factors have different effects.

- Clothes made from plucked otter ("Sealotter") around 1900

Otter jacket with sable trim

- Leaving Otter Skin (Working Sketches)

Sea otters

- 1892

Sea Otter Skins ( Unalaska )

Fur and bristle dealer Joseph Garfunkel in a sea otter coat at the fair in Irbit

In addition to the ariranhas, the largest of the river otters, the sea otters also stand out as sea creatures and because of their special size from the other varieties. The sea otter fur was once one of the most valuable types of fur, it was considered to have an almost unlimited shelf life (which can only be seen in relative terms, however, after a few decades the pelts decay due to natural aging in the leather, like all other types of fur. If you want to keep them, they will applied to a textile substrate). In the past, due to their rarity, Chinese sea otter skirts ( mandarin fur) up to 100 years old were often offered at the London tobacco auctions. They were still good in the hair, only the leather threatened to crumble when wet. The durability coefficient for sea otter fur is 90 to 100 percent.

The sea otters , sea otters, Kalan , formerly false fur designation Kamtschatkabiber or Seebiber, rarely reaches a body length of 1.20 meters to 1.50 meters, but over 1.30 meters. The hair is perpendicular to the scalp, not inclined to any side. The hair is of even length, when blown in, the hair spreads out evenly on all sides without the hair base becoming visible. The hair is of medium length, finely silky, very soft and very dense. The upper hair protrudes only a few millimeters from the lower hair. The tail is fine and densely hairy. The coat color is light brown to deep bluish black, velvety, shiny. The guard hair is often whitish, which makes the fur appear to be covered with a silver veil. The silver coating is strongest on the neck and weakest in the back. While the dewlap is often completely silver, it is completely absent in the back. Older animals have a particularly large amount of silver, young skins (English cubs, Russian medwediki) are lightly silvered; they have longer and coarser hair. The head is lighter than the rest of the fur, mostly black with a brown tinge or more or less silvered on a brown to blackish background. Lips and chin are white. The head of older animals is almost pure white. Usually the throat, neck, chest and front abdomen are also lighter. The feet have no silver whatsoever, the hind feet are lighter than the front feet.

In the case of the shorter, lighter summer coat, the brown-black basic color is more pronounced than the winter coat due to the lower white-tipped awn hair, especially in the Asian origin. The difference is less with the American varieties.

At the withers , where the longest hair is found, the average length of the guard hairs is 27.7 millimeters, that of the woolen hair is 22.5 millimeters. The shortest hair is on the tail, here the guard hair is 18.5 millimeters and the woolen hair is 15.1 millimeters long. The hair is very thick. In summer fur there is an average of 20.2 guard hairs and 1674 wool hairs per square centimeter, in winter 17.2 and 2221 respectively. According to Brass, the fur is best developed in October.

The sea otter is the second largest species of otter after the ariranha or giant otter, but has the largest pelts. The fur of the sea otter is extremely impressive, as it is stripped and stretched about twice as big as the already large animal, due to the strangely loose wrinkled skin covering the body (stretching increases the length by up to 30 centimeters).

The raw hides were mostly delivered uncut, round, those from Japan were open and very well stretched.

The residential area of the sea otter extends in the north to the Arctic, in the south to the tropics. As a result of ruthless hunting, the animals have been extremely decimated, in some places they have become extinct. The “Convention for the Protection of Seals”, concluded in 1911, also includes the sea otter in order to avert the danger of complete extinction. The herds have increased considerably in the protected areas, especially since the aforementioned convention has been extended and supplemented repeatedly in the meantime. In 1977 the subspecies Enhydra lutris nereis (the population of the USA) was included in Appendix I of the Washington Convention on Endangered Species (absolute trade ban), the other populations are in Appendix II.

Before the Seal Convention was enacted, a tobacco shop in Leipzig noticed that almost all of his skins had a rubbed area under the right or left front fin. This seems to be due to the animal knocking open the mussels there with a stone (see article sea otters ).

For the first time in 57 years, the catch of 1000 sea otters was allowed, probably to meet the complaints of coastal fishermen against food competition. They came up for auction in Seattle in 1968. The order from the Alaska government to work on a women's model coat in advance went to the Otto Berger company in Hamburg. Because of their rarity, the skins fetched prices averaging DM 250 to 600 at the Seattle Fur Exchange auction with a maximum price of DM 2,300. Some skins had previously been offered at the Leningrad fur auction. The auctioneer for the most expensive fur in Leningrad was the Marco company , Fürth, the second German buyer was Richard König's traditional tobacco shop . The interest in the world market has practically died down since then, the fur is too heavy for today's fashion, as far as is known, no other fur has come onto the market so far. Around 1969, a sea otter skin that was shown at the Frankfurt fur fair , perhaps that of the Marco company, attracted a lot of attention because of its impressive size and rarity.

All rubbish from the sea otter was also recycled, heads, paws and tails.

History and processing of sea otter skins

When the Russian conquerors came to Kamchatka, the inhabitants there wore fur clothing, which was mainly made of sea otter skin, and it was also used for "domestic purposes". At Prince William Sound , southern Alaska, James Cook found the majority of the Eskimos clad in sea otter skins. On the Queen Charlotte Islands , the coastal Indians wore fur collars made of three good hides, each of which was cut in half, the pieces neatly sewn together in a square and tied loosely over their shoulders with thin straps. On the Vancouver Islands , the collars were made of woven raffia, the upper and lower edges were lined with otter fur, and the gentlemen wore whole coats from them, especially on special occasions.

Georg Wilhelm Steller reported: “In the countries of Kamchatja there is no bigger state than a dress sewn together like a sack, which is called a parka. It consists of white skins from reindeer calves , which are called pushiki, and these are edged with a hem of sea otter skins ; Gloves and hats are also made from sea otter skin. ”According to Steller, tails were also highly valued and sold for 1½ to 2 rubles at the time, while a whole fur of the very best quality brought in 25 to 30 rubles. Since the hair on the tail is thicker and finer than on the head, the coastal Indians always cut off the tail and sold it separately. Von Lichtenstein mentioned: “Even on hides that are otherwise bad and worn, the tail is still of value because the animal takes it under its body when sleeping and its hair does not freeze on the ice like that of the trunk and pull it out when it gets up ".

For more than 150 years, most of the pelts produced went through the market from Kjachta to China, where they were used for the garments of Chinese dignitaries.

In Tsarist Russia, officers' uniforms were decorated with sea otters. Of the skins previously divided into six collars of the same size, two collars were required for a uniform, one for the double stand-up collar and one for the cuffs; the two back surfaces were best suited. To cover the parade uniforms of the hussar officers, a large skin with five to six collar areas was used. By the beginning of the First World War (1914), 90 percent of sea otter skins went to Russia.

Because of its heavy weight, sea otter fur is not suitable for women's clothing, which is why it was mainly used to make sleeves and jacket trims in the mid-19th century. Only when skins came onto the world market via the Seattle auction in January 1968, thanks to the further development of fur finishing, were able to tan the skins much more easily. This opened up new possibilities for use, and the greater need for the Russian army had ceased to exist. In the absence of any noteworthy deliveries, however, this was of no consequence.

In 1902 a German furrier, who worked as a workshop manager at Révillon Frères in Paris, remarked: “The processing of sea otters is relatively easy because of the almost even color and smoke of the hair. The line of the hair is also barely noticeable and allowed, for example, sleeves to be cut across the fur ”. Obviously, these are plucked sea otter skins that have been freed from awns.

Until it was placed under protection in 1912, sea otter skins were mainly used to make trimmings on men's furs, as mentioned, one large skin was enough for five collars. The value of the collar was based on beauty. In black and slightly white-haired pelts as well as exceptionally beautiful, uniformly silvery pelts, which were very rare, it was the back collars. In the case of medium good-silver skins, the side collars were usually much more abundantly interspersed with white guard hair tips and therefore more valuable than the back collars. The next in value was the pump collar, the collar made from the rear end of the fur. Since it was abundantly provided with silver, it was often the same as the back collar, despite the lower hair quality. The head collar, on the other hand, usually fell off a lot, as the skins either have very thin or very white heads, which is why they were mostly used for other purposes with the other sloping pieces. Only small, thin-leather sea otter skins should be used for women's coats.

In 1968, Effi Horn wrote in her book Furs on the legendary durability of sea otter fur: " The investment was not bad: Grandfather's sea otter collars can still be found in some modest wardrobes today, of course now lighter and more yellow, somewhat scuffed or even crooked ."

Sorting and evaluation of the sea otter skins

The different evaluation according to geographical origin, which is usual for other types of fur, does not seem to have existed for sea otter skins. The evaluation and sorting was based on the color and the shine of the coat, in particular on the changing sprinkling of the silver tips. The Russian-Siberian buyers made gradations that probably corresponded to the tastes of their best customers, the Chinese. Steller gives the following distinction: “Of the most precious hides, some are black throughout, others are very white everywhere and shine as silver; but these skins are very rare. Good sea otters have gray, silver-colored heads, on lesser ones the heads are mixed with dark brown and gray, and black-brown hairs too. The worst have no awns, only brown basic wool, but their tails are long-haired and beautifully black. "

However, a specialist fur book from 1988 also identified regional differences:

- Alaska (Sitkafelle)

- Finest quality; darkest color, particularly noticeably silvered. The smallest variety, because of its narrow shape, was called Pijawka (leech) in Russia.

- Japan

- Greater; finest variety; very big attack at the time.

In Russia, the following trade names were used, depending on their nature:

- The finest quality skins = matka (mother); medium-sized dark skins = Koschlock; large skins without silver = Gluhoi (deaf).

The English navigator John Meares (1756–1809) named those skins as most valued when the neck and belly are densely covered with dense burin hair, from which the rest of the body stands out with the finest black hair with a silver sheen. The best kind should be skins from two to three-year-old animals, and winter hides were considered to be far more beautiful and denser than those from summer and autumn. In addition, the furs of males are said to be incomparably more beautiful than those of females, because they are darker black and have velvety hair, while the heads and abdomen of females are covered with coarse hair.

Joseph Billings reported on the differentiation according to age, essentially in agreement with Steller: “The fur of the cubs is coarse and long, of a light brown color (almost like that of young bears) and is therefore called Medweka, which means young bear; it is of no value. The medium-sized ones are darker and more precious, these are called koshlok. But the most precious of all are those who are called matka or mother; the largest of this species are about five feet long [as extensive fur] and have rich, almost black pelts mixed with some longer, shiny, white hairs. The hair stands upright and does not lean to either side, it is one to and a half inches long [25 to 38 millimeters]. "

The last, probably also the decisive classification at the London auctions, was named by HJ Snow in 1910: “The finest furs are black, interspersed with silver tips at a distance of about ¾ inches (20 millimeters). If a fur of this type is full-size, dense and evenly haired and speckled, and evenly colored through and through (except for the head, which is often white), it is considered fur No. 1 and has a high market price. The next tier isn't that dark, but it can be just as beautifully hairy and piqued. Then there are the dark brown pieces, still those of a lighter tint, with or without silver tips; then the sooty brown ones and finally the 'woolly' ones, with short hair with no or almost no awns, which are sometimes ash gray or mouse-colored and look as if the hair was trimmed with scissors. "

mythology

In Germanic mythology, the son of the magician and farmer Hreidmar, Otter (also Otur or Otr) turned into an otter. He was killed with a stone throw by the god Loki. The sir Loki, Odin and Hönir pulled the hide from the Otur. The farmer Hreidmar recognized his son's skin in the otter hide and imprisoned the sir. Hreidmar demanded reparation from the gods: They should fill the stripped hide of the otter with gold and also cover it with gold on the outside. Loki got the gold from the dwarf Andvari, who however put a curse on the treasure. The gold was enough to fill and cover the otter's fur - except for a whisker, for which she had to use the Andvaranaut ring, which had also been illegally taken away. With that the curse passed on to Hreidmar and his clan.

Proust's coat

The coat of the writer Marcel Proust , whose story Lorenza Foschini described in her book, which was published in Italy in 2008 and in 2011 in German, attracted particular attention . Your work was also used as a literary model in the opera Trois contes , premiered on March 6, 2019.

Proust had been wearing the coat since around the age of 20: "From then on he no longer changed this type of clothing and thus gave the impression that time had stood still for him. He looked like an embalmed image of his youth". Proust wore the heavy double-breasted suit "even on the hottest summer days, which has become legendary for everyone who has known it". Accordingly, he was often depicted in this part. It served as a blanket for him when he wrote at night.

On the cover picture of Lorenza Foschini's work, the coat looks dark brown, but costume designer Piero Tosi described it as a “coat made of dark gray, almost black wool, lined with otter skin”. The natural-colored brown-looking collar fur was also described by Foschini as a “collar made of black fur”. There is no company label or reference to the tailor or furrier on the coat.

In 1913, Jean Cocteau made a sketch of the writer wrapped in his coat. The writer Marthe Bibesco mentioned the coat: "Marcel Proust came and sat across from me on a small gold-plated chair, as if he had come from a dream, with his fur-lined coat, his sadly filled face and his night eyes". Paul Morand described Proust in his memoirs as “a very pale man, wrapped in an old fur-lined coat. [...] ".

Proust wrote self-ironically to Philipp Sasson, the grandson of Baron Gustave de Rothschild : “One of your most famous compatriots honored me when he remarked: 'The greatest impression my wife and I have with us from Paris is the meeting with Mr. Proust ›. That made me very happy, but unfortunately too early, because he added: 'We have never seen a man in a fur coat eat before.' "

Proust's coat, wrapped in tissue paper, is kept in a cardboard box in Paris in the Musée Carnavalet on Rue de Sévigné, and is not on public display because of its poor condition.

Numbers and facts

Detailed trade figures for tobacco products can be found at

- • Emil Brass : From the realm of fur. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911

- • Emil Brass: From the realm of fur. 2nd edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925

- • Emil Brass: From the Realm of Furs (1911) ( Digitalisat - Internet Archive )

- • Milan Novak et al, Ministry of Natural Resources: Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America. Ontario 1987 (English). ISBN 0-7778-6086-4

- • Milan Novak et al., Ministry of Natural Resources: Furbearer Harvests in North America, 1600-1984. Appendix to the above Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America. Ontario 1987 (English). ISBN 0-7729-3564-5

| World production of otter pelts The estimates were: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skins | ||||

| 1864 | Heinrich Lomer | 45,000 | ||

| 1900 | Paul Larisch / Joseph Schmid | |||

| North America (Virg. Otter) | 25,000 | |||

| Europe | 30,000 | |||

| Asia | 70,000 | |||

| Africa | - | |||

| South America | 20,000 | 145,000 | ||

| 1923/24 | Emil Brass | 160,000 | ||

| 1930 | IPA - International Fur Exhibition | 160,000 | ||

| 1950 | Friedrich Lübstorff | 80,000 | ||

- 1772 Russian rifle producer Asanessei Orechoff upgraded a fourth expedition on which in Okhotsk built ship "St. Vladimir ”under the command of the helmsman Saikoff. In 1773 Saikoff drove from Copper Island, home to a large herd of seals, to Alaska and the Aleut Islands . The natives exchanged skins for corals, glass beads, copper kettles, tobacco and items of clothing. As a new medium of exchange, Saikoff introduced cat skins , which the Aleutians gladly accepted and which were exchanged for arctic foxes and sea otters . The ship did not return to Okhotsk until 1776, in addition to the tribute to the Russian crown, the yield consisted of 3863 sea otters, 3874 sea otter tails, 583 young sea otters, 549 silver foxes , 1099 cross foxes , 1204 red foxes , 1104 blue foxes , 92 otters, 1 wolverine , 3 Wolves , 1750 sealskin and 370 pound walrus teeth .

- In 1794 50,937 American otter skins were exported to London. In the period between 1800 and 1850, 767,722 otter skins were apparently exported to England.

- After 1800 , around 20,000 sea otter skins came onto the market every year.

- 1801 published by Gerhard Heinrich Buse:

-

Prices:

- In Thuringia, a common otter skin is used by the furrier with 12 rth. and a big one with 16 rth. paid.

-

In Orenburg Of the great variety I St. I Rub. 50 cop.

- medium - I rub. 20 cop.

- small - I rub.

- otherwise - 3 to 4 rubles.

-

In Kjachta river otters 2 to II rub.

- Bellies 30 Kop.

- In London Canadian 26 to 26½ Shelling

- A beautiful hide from the sea otter is worth from 90 to 140 rubles, and the tails, which are common with hats and gloves, are paid from 3-7 rubles.

-

Price in Petersburg:

- long and 1.5 wide - 150 rubles

- medium - 50 rubles

- lower - 25 rubles

-

Price in Kiachta:

- Bobry morskye, old (Matki) - 90-140 rubles

- medium (koshloki) - 30 to 40 rubles

- Tails 2 to 7 rubles

- 1864 , Heinrich Lomer: So you need them in Bavaria for hoods for women, in Prussia for hats for hussar officers, in Canada for long women's gloves. The price of otter skins is 4 to 20 thaler per piece .

- In 1891 only 3,000 sea otter skins came on the market, in 1880 a skin cost “1,200 marks, 1890 ... 4,000 marks, 1914 already 8,000 marks”.

- In 1910 31 ships looking for the sea otters captured only 30 of them.

- In 1911 , the tobacco merchant Emil Brass estimated the quantity of land otter pelts that came onto the market every year at around 30,000 pieces.

- Baghdad otters, Indian otters, Himalayan otters, come from Burma, Malacca, Sumatra and Java, these Asian otters were of little importance at the time, only a few came on the market, the price of a fur probably rarely exceeded 3 marks: .

- Increasingly came before 1911 Chinese qualities on the market (annually about 25,000), the price averaged 10 marks each. Even earlier the guard hair was removed from the skins, at that time it was not plucked.

- The skins of the Japanese otter, which is very different from the Chinese otter, were only rarely exported because they were plucked inland and processed into fur collars.

- Before 1911 , 2000 to 3000 otter skins were sold annually from Africa .

- 1912 Great Britain, Russia and Japan prohibit fishing for sea otters in the open sea. The agreement was later extended several times.

- In 1913 , 81 sea otters were caught.

- In 1924 , the prohibition of commercial fishing for sea otters was issued in Russia.

- In 1930 , according to statistics from the IPA (= International Fur and Hunting Exhibition in Leipzig), 160,000 otter skins were produced worldwide.

- In 1934 the otter was completely protected in Germany.

- Before the Second World War (1939 to 1945) Canada supplied an average of 10,000 to 15,000 otter skins annually, the Soviet Union between 5000 and 10,000, 40 percent of which came from Siberia.

- Before 1944 the maximum price was

- for European otter skins 90 RM

- for North American otter skins ("Virginian")

- natural color dark 350 RM; light 200, - RM

- blinded large 150 RM; small 80 RM, -

- seal-dyed large 160 RM, -; small 80 RM.

- In 1951 , Alexander Tuma wrote in his fur lexicon that at the time there was a fishing permit for 15 sea otters a year.

- In 1959 , around 100 extra small Asian otter skins, apparently from Baghdad, were offered at a February auction in London. The fur length was about 35 to 45 centimeters, they were medium smoke, light colored, rounded off. The tobacco expert from Frankfurt, who had purchased the goods, commented that during his 45 years of shopping activity, such a "large" range of small otter skins had never been delivered.

- In 1960 , the annual incidence of Argentine origins was given as 2000 to 3000 furs.

- In 1962 , the USA carried out sea otters for the first time again.

- From 1965 to 1980 , the number of otters caught in North America nearly doubled, with the annual harvest in the late 1970s being around 50,000 pelts valued at around $ 3 million (Deems and Pursley 1983).

- 1966/67 , that season, the US yield was 16,980 otters.

- In 1971/72 , 15,261 otter pelts were recorded in Canada, each yielding an average of $ 33.5.

- In 1983/1984 Canada produced 15,850 pelts at an average price of $ 18.71. In the USA there were 17,285 skins (together 33,135).

- In 1988 , the worldwide incidence of otter pelts was estimated to be well below 100,000.

literature

- Adele Ogden: The California Sea Otter Trade • 1784-1848 . University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1941 (English) → Table of Contents .

See also

annotation

- ↑ a b The given comparative values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco merchants with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are not unambiguous; in addition to the subjective observations of durability in practice, there are also influences from fur dressing and fur finishing as well as numerous other factors in each individual case . More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The most durable types of fur according to practical experience were set to 100 percent.

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c d e f Heinrich Dathe , Paul Schöps, with the collaboration of 11 specialists: Fur Animal Atlas . VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1986, pp. 185–190.

- ↑ a b Paul Schöps; H. Brauckhoff, Stuttgart; K. Häse, Leipzig, Richard König , Frankfurt / Main; W. Straube-Daiber, Stuttgart: The durability coefficients of fur skins in Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume XV, New Series, 1964, No. 2, Hermelin Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig, Vienna, pp. 56–58

- ↑ Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: The fineness of the hair - the fineness classes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. VI / New Series, 1955 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 39–40 (Note: fine (partly silky); medium-fine (partly fine); coarse (medium-fine to coarse)).

- ↑ Anna Municchi: Ladies in Furs 1900–1940 . Zanfi, Milan 1952, English, ISBN 88-85168-86-8 . Primary source D'Annunzio under the pseudonym "Happemouche" in: La Tribuna , Rome, in the column "Cronachetta".

- ↑ [1] . Version 2015.4. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel ´s Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10. revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, pp. 66–72.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse, Richard König , Fritz Schmidt: The otter . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XI / New Series, 1960 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig, Vienna, pp. 6–20.

- ^ Heinrich Lomer : The smoke goods trade . Leipzig 1864, p. 62.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, 509-517.

- ^ A b c d Milan Novak et al., Ministry of Natural Resources: Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America . Ontario 1987, chapter 47 River Otter (English). ISBN 0-7778-6086-4 .

- ^ The Department of Information and International Relations, Central Tibetan Administration: Tibet 2003: Environment and Development Issues . Tibetan Government-in-Exile White Paper, Dharamsala July 2003, unauthorized translation from English. [2] .

- ^ Francis Weiss : From Adam to Madam . From the original manuscript part 1 (of 2), here p. 51.

- ^ Heinrich Lomer: The smoke goods trade . 1864 , p. 41

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Rheinische Friedrich-Humboldt-Universität Bonn, 1900. pp. 15-16. Primary source Steller p. 128.

- ^ Peter Nath Sprengel: PN Sprengels Künste und Handwerke in tables , volumes 5-6. Verlag der Buchhandl. the royal Realschule, Berlin 1790, p. 85

- ↑ Paul Schöps among others: The material requirement for fur clothing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVI / New Series 1965 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 7-12. Note: The information for a body was only made to make the types of fur easier to compare. In fact, bodies were only made for small (up to about muskrat size ) and common types of fur, and also for pieces of fur . The following dimensions for a coat body were taken as a basis: body = height 112 cm, width below 160 cm, width above 140 cm, sleeves = 60 × 140 cm.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse, Richard König , Ingrid Weigel: Der Seeotter . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Jg. XIX / New Series 1968 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig, Vienna, pp. 8–31.

- ↑ www.fortrossstatepark.org: Robin Joy: More about the Sea Otter (English). Retrieved March 13, 2012

- ↑ Dr. Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: For the storage of fur , chapter The life span of refined and made-up goods . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume VII / New Series No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Leipzig 1957, p. 66

- ^ A b Emil Brass: From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition, publisher of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, pp. 161–190.

- ↑ a b Without indication of the author: Der Seeotter . In: The tobacco market XXXI. Vol. 9/10, Leipzig February 26, 1943, p. 9

- ↑ a b A. R. Harding: Fur Buyer's Guide . Self-published, Columbus, Ohio 1915, pp. 338-341 (English).

- ↑ Without a statement by the author: Berger produces the first sea otter coat . In: Rund um den Pelz , No. 10, October 1967, Rhenania Verlag, p. 83

- ↑ Without the author's details: Marco bought the most expensive sea otter skin . In: “Marco - information from the Franconian fur industry Märkle & Co ”, Fürth December 1967, pp. 2–33. Advertisement by the Seattle Fur Exchange: Sea Otters. First auction since 1911. For the account of the State of Alaska. Only 1000 skins. Date of sale: January 30, 1968 . (Note: The sources cited do not reveal why the fishing quota, which was limited to 1000 skins according to the Fränkel's Rauchwaren-Handbuch, was apparently exceeded with the Leningrad offer.)

- ^ J. Cook, King: A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean . London 1785, Volume 2, p. 295. Secondary source Arnold Jacobi.

- ^ J. Jewitt: The Adventures and Sufferings of John R. Jewitt, only Survivor of the Ship Boston, etc. Edinburgh 1824. 8. German: John Jewitt, Makwinnas Gefangener. My adventures and sorrows with the Indians at Nutkasund . Leipzig, 1928, pp. 42-43. Secondary source: Arnold Jacobi.

- ↑ a b c d Arnold Jacobi : The sea otter . Series Monographs of Wild Mammals , Volume VI, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig 1938, pp. 55–67.

- ↑ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: The furrier craft . III. Part, self-published, Paris, November 1902, p. 57.

- ↑ Paul Cubaeus, Alexander Tuma: The whole of Skinning . 2nd revised edition, A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna, Leipzig 1911, pp. 352–353.

- ↑ Effi Horn: Furs . Verlag Mensch und Arbeit, Munich 1968, p. 161.

- ^ HJ Snow: In Forbidden Seas. Recollections of Sea-Otter Hunting in the Kurils . London, 1910, p. 273.Secondary source Artur Jacobi, p. 57.

- ↑ Lorenza Foschini: Proust's coat - the story of a passion . Nagel & Kimche in Hanser Verlag Munich, 2011 ISBN 978-3-312-00482-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Fritz Schmidt: The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer Verlag, Munich 1970, pp. 282-287, 328-333.

- ↑ Gerhard Heinrich Buse: The whole of the plot . Erfurth 1801, section otter skins , p. 54 (secondary source Schöps, in Das Pelzgewerbe 1960, issue 1).

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, pp. 53, 73.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XXI. Tape. Alexander Tuma publishing house, Vienna 1951. Keyword “Seeotter”.

- ↑ Milan Novak et al., Ministry of Natural Resources: Furbearer Harvests in North America, 1600-1984 , Supplement to Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America . Ontario 1987, p. 188 (English). ISBN 0-7729-3564-5 .