Fur scraps

Fur remains ( Greek Chordas ) are in the Skinning mentioned in the fur processing sloping fur pieces, pieces in the industry. They are assembled into semi-finished fur products , so-called “bodies”, which are mainly processed into fur clothing and fur blankets . A small part goes into the haberdashery and, currently hardly in Central Europe, into the toy production. Pieces of fur are used as bait when fly fishing . Increasingly after the Second World War , fur remnants are now rarely processed directly into larger items of clothing by the fur-processing furrier. The specialization of individual companies in this activity reduces the working hours required for this to a considerable extent, and it also enables the collection of large quantities of similar items. The preprocessing allows a more advantageous, effective fur finishing , with shearing for the shearing process, with dyeing it creates the possibility for the additional application of patterns with spray guns, possibly with the use of stencils. Relief-like patterns are occasionally created by burning out the hair with lasers. The bodies are mostly sold through tobacco wholesalers and return from there to the clothing industry or to the furriers who operate in retail. The sloping parts of the fur are usually more lightweight and usually have the same, sometimes even greater durability than the main product made from the core pieces of the fur.

The fur processor only occasionally uses the leftovers in the fur production in a concealed place in the jacket or coat or integrates them as an ornament. However, indigenous peoples in particular , such as the Eskimos , have developed costumes with very artistic, harmonious patterns that are made from the pieces of fur that would otherwise fall off. Everything indicates that the fur remnants, which are still valued today, have been used since humans have processed fur into clothing.

In the last few centuries, various centers around the world have developed their own industries for processing pieces of fur, in Europe this is still mainly Kastoria in Greece and the nearby town of Siatista .

The German RAL regulations for fur clothing published in 1968 state that for an honest description of the goods, fur goods, if they are not made from whole skins, i.e. from sides, dewlaps, claws, tails (tails) or pieces of waste, must be marked as such (for example Mink paw coat, not mink coat). In the text of the provisions, special attention is drawn to the fact that the terms "from the best pieces" or "from selected pieces" or analogous terms are not permitted.

In 1961, an ordinance on making the condition of hides and fur goods of the Austrian Federal Ministry for Trade and Reconstruction clear: " § 4: For fur goods that are not made from whole pieces, this fact must be pointed out (for example Persian piece coat) , or the parts of the fur used are to be listed (for example muskrat coat, saddleback coat, Persian head coat, Persian claw coat ). "

For a description of the different types of fur, see → Types of fur and the links there to the relevant main article.

General

In addition to the "weft goods", the mostly extremely damaged pelts that cannot be used for normal use, head pieces, paws and tails in particular are generally not taken into account for the time being, if only because the pelts are irregular fur shape so cannot be used. Also, these parts usually differ considerably from the rest of the coat character. Leg parts and tails almost always have a different color than the torso, the leg parts and the head pieces are often shorter-haired. In Persian and other curly lambskins , the leg parts, called claws by furriers, are less curled, only moiré or completely smooth-haired. The tails, when they are densely hairy, are always long-haired. Often the different colored belly side, the dewlap, is processed separately. One of the special remnants arose from the Skunksfell , where the light and long-haired fork used to be poked out, put together and dyed dark.

An exception is the guanaco fur, in which the very long legs are often left on the fur and, especially when used for fur blankets, the furs are artfully combined, a processing method that was already mastered by the Indians . The light, almost white fur areas that merge from the legs into the sides of the fur create a characteristic image for this type of fur. Nevertheless, this material-saving method of working still left fur residues, which were put together by the Indian women together with small skunk skins, wild cats and other domestic skins to create impressive, tasteful patterns.

For rabbit paws, the use for glue production was mentioned in 1950. The remnants that cannot be used for fur purposes and the so-called small pieces are otherwise used for animal hair recycling, especially for the production of felt. Hatters mainly used beaver, muskrat, nutria and rabbit, but also mink, otter and mole. Beavers, muskrats, otters and nutria are used for the outside and give the felt a smooth surface. In 1930 the production process was described as follows: The so-called "blown fur" is blown through a machine and mixed with other materials used in felt manufacture. The pieces of fur are glued onto a strip of paper that runs over a roller and then through a machine. The fur then comes into contact with a rotary knife, which cuts the fur very briefly. At the same time the cut fur is blown into a container. However, because of their even more beautiful shine, the hatters preferred the pieces of raw fur. - The hair of long-haired, strong fur goes into the brush industry as brush goods (e.g. bear, badger, goat), tail hair is used for finer hairs (e.g. Kolinsky, Feh). Waste in the hair-cutting industry (schnitzel, leather pasta) was used as vineyard manure in France, among other places.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the name was Tafelmacher and board champion for the furriers, who engaged in the production of fur panels and coat linings. Originally they did not appear as independent furriers, but were employed by a furrier for this special work.

The invention of the fur sewing machine represented a revolution in fur production, especially in the sewing-intensive processing of pieces of fur. In 1894 the first machine was imported into Kastoria, but initially it was taken out of service because of the protests of the seamstresses who feared for their jobs.

In 1928 a furrier Manual dismissed those furriers who use the waste as a special work out that one has now invented a punching device which concerned the time-consuming cutting the small Fellstückchen quickly and evenly. These punches, like the whole device, work in such a way that the hair is not cut off. The punches are interchangeable for the individual shapes and enable quick and meticulous work.

At the end of the 19th century, the fur pieces began to be used not only for inner lining, but also on the outside for “ladies' jackets”. The tobacco merchant Francis Weiss ascribes the idea of manufacturing bodysuits, semi-finished products from fur, to Kurt Seelig, of New York, of German descent. After the Second World War, Seelig was the first to supply, in addition to the previous fur boards or linings, perfectly assorted fur sheets in the size required for coats and jackets, also known in America as “fur shells”. At the same time, body production was started in Greece, but here from pieces of fur.

- Early fur patchwork work

Special trade names

According to size (each width x height)

The usual dimensions vary depending on the fashion and intended use (jacket or coat).

- Body = coat 230 cm × 118 cm; Jacket 230 × 75 to 90 cm.

- Lining , usually made of fur only = 110 to 115 cm × 140 to 150 cm (conical, usually narrower at the top).

- Plate (plate), unusual for pieces, actually only for Chinese fur tablets = 60 × 120 cm.

- Stripes , etc. a. Mentioned in 1958: 120 × 45 to 50 cm, so strips are narrower than panels .

According to the skin part

- Nourkulemi = rear part of the belly of the marten-like ; little guard hair, sometimes white spots, light. Mostly mink and sable.

- Thiliki = part of the chest behind the front paws, of marten-like. Mostly mink and sable.

- Tail = thickly hairy fur tail .

- Claw = paw of ungulates, especially Persian sheep (not entirely correct, but also very often for fur paws of other species). After the technical term "claw" had been changed to the zoological term around the 1980s, mainly in northern Germany, an "expert commission" declared both terms to be correct.

In the fur industry, these Greek terms are not used in German-speaking countries, for head = kephali; Front paw = prostino podi; Hind paw = pisino podi; Pump (rear end of fur) = Founta; Side = kiles; posterior or anterior side of the heart = cardias; and Maschali, a side piece behind the front paws. They are named according to the part of the body they come from (mink headpiece body, sable front paw body, etc.).

According to processing type

- Palmera = left and right paw side by side in pairs like a chessboard. With fox paws, very decorative.

- Vintom = diagonal. Bodysuits are made from the left, right and left halves of the skin, one with slightly staggered layers of skin rising to the left and the other to the right. The further processing of only one half for an item of clothing causes the item of clothing to fall on one side due to the stiffening, diagonal seams. It is almost only used for Chinese squirrel tablets, which, like the muskrat tablets, are not counted as piece products.

Use according to skin parts

Depending on the fashion, the following fur parts are or have been worked into semi-finished products without claiming to be complete:

- Heads

Australian opossum , muskrat , Feh , veal , rabbit fur , sheepskin , mink , Persian lamb , Ross skin , sheepskin

- Paws, claws

Foal , fox , calf, lambskin, Persian, horse skin, sheepskin, Shiraz , mink, kid , goat

- Pumps (rear parts of the fur, in front of the tail)

Muskrat, rabbit fur, mink

- pages

Australian opossum, foal, chestnut, calf, rabbit fur, marble , mink, nutria , viscacha , kid

- forehead

Muskrat, rabbit fur, mink, sable, horse

- to bake

Muskrat, rabbit

- neck

Mink, lamb

- Throats

Pine marten , muskrat, polecat , mink, stone marten , sable

- Ears

Chinese lambskins , kid , formerly rabbits, squirrel ears as a conclusion to artificially twisted ermine tails

Bars made from ears in China were once very popular. With all types of fur, the inside of the ears had to be removed first, which required a sure instinct and skill. The soft tops of the ears thus obtained were sewn together to form artistic patterns and lined with fine silk. This technique of staying is now one of the crafts that have died out. Since the Middle Ages, all attempts to find a satisfactory solution with which the ear panels can be permanently reinforced have failed.

- Skunks forks

The white strips of the skunk fur were cut out, made into narrow strips and then dyed.

- Pieces

Depending on the suitability from the different types and types of fur

- Tails

(Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Die Krüppel , 1598)

- The tails are used differently, mainly because of their nature and shape.

- Feh, foxes, martens, mink and sable have thickly haired, strong and bushy tails .

- In cat species - small cats ( house cats , wild cats) and large cats ( tiger , lion , leopard , jaguar , puma , clouded leopard ) - the tail is long but slightly hairy. The heavily haired snow leopard ( Irbis ) is an exception .

- Of the Australian marsupials , the opossum ( kusu species ), ringtail and wallaby have long tails, koala fur and wombat are tailless.

- Bear , badger , hare , rabbit and lynx have stubby tails .

- Some fur animals have hairless or slightly hairy tails , such as the beaver , muskrat, nutria, and mole . In countries in which catch premiums are paid for the muskrat, the tail must be submitted to the authorities as evidence of the catch ( tail premium ).

- In the past, fox tails were often used, in addition to cat skins , to generate static electricity for an electrophore , a historical influenza machine for separating electrical charges and for generating high electrical voltages "by hitting it with the fox tail".

- Tails are rarely processed with the fur, if only because they are very different from fur, for example as trimmings or decorative edging on scarves and capes. As tags on key rings and other everyday objects, they have been used to varying degrees in the last few decades. In the 1970s, a fox's tail was a symbol for “ chubby ” Opel Manta drivers who used it to decorate their car antennas. Even a bonanza bike wasn't actually complete without a red fox tail at the same time.

- An exception are the necklaces, fur scarves in the shape of animals, which are seldom offered, where a beautiful tail is of course part of it. Occasionally, necklaces are still made from fox skins, currently no longer made from wolverine and wolf, nor are the necklaces made of marten and mink, which were very popular until after the Second World War.

- Depending on their usefulness, the skins come with tails on the market. Around 2009, the major auction companies started bringing fox skins without tails to auctions. The reasons given were the saved tanning and transport costs. It has been shown, however, that the tails are now so popular that the breeders market and advertise them separately, for the 2016/2017 season of Copenhagen Fur as “very hot this season”. In recent years they have been used to a particularly large extent, especially as pendants on bags and many other accessories, either as pompoms or in full length. As of 2016

Lambskin ankle boots with mink tail trim (approx. 1960–63)

Types of fur

The following is a list of how the leftovers are used for the various types of fur:

- Monkeys , the sloping gray pieces filling the star-shaped and round mosaic fur lids for foot baskets (1911).

- Antelope, gazelle , antelope or gazelle waste can be used for mosaic work and for the toy industry (1928).

- Astrakhan (Merluschka lamb) , carefully matched in the claws and heads, material for covers on gloves and hunting mugs, also jackets, coats and caps (1911).

- Bears , the claw pieces can only be used on holsters or as wagon kicks, other pieces are bought from brush manufacturers (1895). Bear pieces of all kinds for brush manufacturers (1911).

- Beavers , beaver sides for lining, pumps for the lids of beaver hats (1895). Beaver and muskrat pieces, including the smallest sections, are lively coveted and well paid for by hat fabric manufacturers. In addition, the foreheads of beavers, with the smoke placed next to each other as a front trim on furs, can be used very well, large pumps are excellent for caps. (1911). For many years, the high value of the beaver was only made up of the soft undercoat from which the tall, broad-brimmed, so-called castor hats were made, and less of the overall fur. The use of beaver fur for the fur industry began around 1830.

- Muskrat , of Bisamköpfen, the eyes and ears holes by two cuts, along continuously from the eye over the ear, removed, triangular cut and star pattern composed, just by the Pümpfen, foods are put together (1911). Muskrat pieces make pretty piece of lining for furs and jackets. Hat manufacture also has a use for it (1928).

- Chinchilla , of the chinchilla waste, only the heads can be taken into account, which, if there are enough, are used for starfing similar to musk heads (1895).

- Badger , long-haired pieces of the kind that fall out of the middle when cutting tourist lids, for example, are a valued material for brush makers, ( see above ) and for tipping pelts (tips, the insertion of light hair into cheaper types of fur to imitate silver fox ) (1911 ).

- Feh , the artificial production of fur tails was once an important branch of the fur industry. The artificially corrected tails were particularly popular. The tails of the Russian squirrels, cut off by the smokers' dresser or the fur trader, were sent to the feudal manufacturer , who had them dressed (tanned) and usually also colored. The frog tail is two-lined, that is, the hair goes in two directions. To embellish this, in the artisanal version, the furrier pulled the damp tail with a long needle and string and then twisted it. To make it not only fuller but also longer, he put two or three pieces on top of each other or cut them into each other and then twisted them into a single tail. The twisting of the tails was done by specialist companies around 1900, according to the great demand at the time and the high incidence of skins, a large number of companies dealt with it. On the tail lathe, they produced tails of various thicknesses - 1 to 15 times - turned, the 15 times with the highest material consumption were the strongest. Each degree of strength was initially calculated with a groschen, i.e. 10 pfennigs. Twisted tails up to one meter in length were also made. These were bought from the frog tail clothing that they used for capes, trimmings and trimmings. Boas were made in the same way (see → tail turning ). The brush ears of the false fur were also used. Dyed black, they served as the tips of the twisted ermine tails.

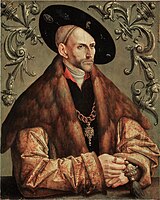

Costume made of missing throats

( Revillon Frères , Paris, 1967/1970, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- Foals and pieces of foal are excellently used as lower throats for heads. They are also used for hunting muffs and for mosaic work (1928). The hair of the foal's tails, like that of the horse's tails, is made into horsehair . Cheap coats were made from the remaining waste, especially the claws.

- Foxes , the fox claws are used for gloves, which are lined with a slight smear , because of the difficulty, in some places they were part of the masterpiece. The fox ears can only be used for mosaic work. The fox tails, however, are a popular item. The better varieties are used with preference for foot pocket trimmings , while the smaller ones are broken up into pieces and twisted into foxtail boas . Also cut into strips and stapled on canvas, they give fur linings and blankets, even if this work cannot be called solid. Fox tails are also used as electricity generators, as dusters and finally as jewelry for harnesses (1895).

- The tails of the foxes are only used here [Russia] to pad the pillows and bed mattresses (1814).

- No woman in the world has such a fairytale treasure trove of precious furs as the Queen of England ( Maria von Teck , Queen Mary, the wife of George V ) . [...] A fur that she wears on trips is a marvel of Siberian fox fur; it is made from a multitude of foxtails, all of which fit together exactly and are so artfully put together that even on closer inspection they are mistaken for a single gigantic piece of fur (1921).

- Today fox tails are mainly used for trimmings on hoods and collars and as pendants. All other types of fox pieces are sewn together to form bodies that are processed into all the fur products that occur.

Zhang Ziyi with upper arm cuffs made from pieces of fox ( Berlin International Film Festival 2013 )

- Geese and swans , the waste is plucked and used as filling material for muffin bags. For some larger side pieces can be powder-puffs produced (1911).

- Grebes ( Gröbis ), also aspecies of bird usedfor fur trimmings, scraps of Grebes are sought after by feather dressers, if the fashion demands it, and the many damaged furs that occur in the large lots and have already been discarded by the trader are from them, gladly bought (1895). Wings that fall off are made into beautiful sets of seal canine or seal bisambarets by attaching them to the heads or half small skins (1911).

- Rabbits , individual pieces of [snow] hare skins are sewn together for the trade and thus the back, side, stomach and ear bags are obtained. The ear sacs are hairy on both sides, have a Hermelin-like appearance due to the black tips of the ears and are therefore popular (1844). The ears of country hare are often put together, that is, stapled next to each other on canvas and used to make hunting muffs and caps. However, this work is not to be recommended. The hat manufacturer takes everything else, with the exception of the black pieces, which can only be disposed of in exceptional cases at toy manufacturers. Tails are twisted from colored hare pieces (1911). Black rabbit pieces go to Krampus fabrication, otherwise black as well as fashion-colored rabbit pieces are wanted for tail manufacture (1928). Rabbit paws are considered a lucky charm. It is also said that the hare's paw was put into the leotard by ballet dancers to reinforce their masculinity, in order to have an erotic effect on the female audience.

- Ermine , it is necessary to free so-called "bone tails" from the tail. For this purpose such tails are carefully tapped (with the back of a pair of scissors or a small hammer), the tail is cut open on the inner side up to the tip and the tail is carefully detached starting from the tip (1885). The pieces are sometimes bought for the production of the imitation tails, but only if they are very beautiful, large and ermine furs are very expensive. The sloping heads of the ermine, drawn moist over half (head) shapes and provided with the smallest, red or blue eyes, are particularly suitable for decorating children's sets (1911). Ermine tails serve, among other things, as fringes on scarves. For centuries, the ermine tails with their black tips demonstrated the authenticity of the material by sewing them onto the ermine clothing of kings, popes and subordinate higher classes as well as rectors. Ermine tails were also often imitated. The tail was made of Chinese white rabbit fur, the tip of black cat fur. This work was mostly done by Greek furriers in Paris, Leipzig and other fur fields. The heads will only be used as surface mounts (1928).

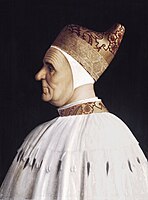

Hermelin cape of a Venetian doge , with tails. The front paws were left in the fur (15th century)

- Iltis , Iltis pieces are bought by the Greeks for assembling chucks, the heads are nice drawing for naturalized for decorating Jagdmüffchen even triangular cut for Mosaikfußkorbdeckel. The tails are wanted for brush manufacture (1911).

- Kanin , the goiters are to be assembled in large specimens as cuffs, preferably smaller than trimming. Large pages can often be put together to form stand-up collars, etc. Everything else is used by hat fabric manufacturers as shear material, with the exception of the black one (1911). Today, tanned hare and rabbit pieces are out of the question for hat production. There is so much raw cuttings for this that one no longer needs to access the waste, which also no longer has the hair quality required for hat felt manufacture (1928). Around 2007, as an import from China, small clothing made of rabbit heads or rabbit cheeks in the form of sleeves and scarves came onto the German market for the first time at a very low price.

- Cats give little waste. Damaged, good cats can be used as spots in white rabbit mugs. Tails have little value or usefulness (1911). Paintbrushes were made from the tail hair of the civet.

- Kolinsky , the hair of the Kolinsky tails, are used to make fine paintbrushes.

- Leopard , leopard pieces are very well used in mosaic work to depict the rocky areas (1928).

- Lynx , pieces of lynx are often so downy that, when put together, they still look pretty as trimmings (1928). The lynx paws are very large, they can be made into trimmings and small parts, and the low-rated back parts must also be used separately. Otherwise there is usually hardly any usable waste.

Lynx cat head pieces, ear holes closed with a fur sewing machine by a Castorian furrier (2014)

- Marten , the tails of all sable and marten waste make up the main part , but they were mainly in demand in France, Italy and Holland, where they were not only processed into sleeves and trimmings, but also into larger parts such as cape (1885). The foreheads can be used for mosaic foot basket lids, the throats as well and with the claws for the production of linings, which are similar to the sable throat linings, but heavier. The tails are sought for decorating gallantry work and as material for brush makers (1911). Before the First World War (before 1914), pine marten and sable boards in particular, and occasionally stone marten, were particularly in demand with their appealing colors, especially in Russia. The use and processing corresponds to that of the mink.

- Mole and mole pieces are often put together to form mosaic pieces, which, however, do not provide the material for skin pictures, but for stoles and trimmings themselves. You put together very nice designs especially from mole heads. Mole pieces are also used to form reflective stripes (= in opposite hair direction) between two whole skins that have been worked together (1928).

- Marble , marble pieces are assembled to feed, thin-haired pages are processed to mooch (1928).

- Mink ( Nörz ), the Nörz pieces are also put together by the Greeks, the tails, like the marten tails, are used to decorate women's sets and borders. The foreheads also used to make fur lids for foot baskets (1911). Mink tails, enlarged by inserted leather strips and loosened up in the hair, are made into bodies for coats and jackets. In the second half of the 20th century, Peter Pan collar and caps from the material, also with between-stitched leather galons , very fashionable. Mink tails are particularly suitable for the production of costume jewelry due to the hair structure with the protruding guard hair.

- Nutria , hair was once a valued material for hat fabric manufacturers as a replacement for beaver hair, see castor hat . From the often sloping, weaker sides, bodies are made, as long as they are not too thinly haired.

- Australian opossum (ringtail) , the tails of these opossums are gray above, the lower half black. Thick ones make pretty trimmings on foot baskets, blankets are made for the majority by assembling the black from 16 to 20 inside into square stars, and these stars then match and match (1911). The best, bushy tails were occasionally trimmed on men's sports furs (first half of the 20th century). If the market price allows it, bodies are made from the leftover pieces.

- Otters and waste from otters, like that of beavers, are valued and used equally. The larger ones are particularly popular for making fur fantasies and images, for which the pieces of otter are sheared at different depths. Often all kinds of animal pictures, even entire hunting pieces, are artistically produced with it (1885). Fine material for hat material, but mostly put together, plucked and dyed by furriers. The tails give composite, beautiful, durable hunting muff (1911). The tails were also used by the North American Indians as headdresses that the men braided into their long hairstyles. Pieces of sea otters are used in Poland to trim hats (1928).

- After it was possible to dye the Persian fur and the previously translucent white leather deep black through modern finishing, the Persian was one of the most popular types of fur of its time. This was especially true in the Federal Republic of Germany, so that it was considered a classic "German" fur until it was replaced by the mink in the 1970s. Since around 2000 it has been enjoying increasing popularity again, also in Europe, but especially in the new eastern markets, but furs made from Persian pieces and claws are still rarely available in Central Europe (2012).

- The idea of using the claws from Persians is said to have originated in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, until then, according to Jäkel, the remains of Persian and other fur remains were unused. In 1902 Paul Larisch describes the processing of the much flatter and barely marked claws of the Persian broadtail skins , not to be confused with the later bred broadtail Persian : The sloping heads and claws are combined into special panels. The claws usually diagonally in a zigzag shape . The earlier use of the Persian claws corresponded to that of the Astrakhan listed above. Karakul or Persian pieces represent a very special value. The furrier will rarely sell the rubbish, but rather put it together himself in the quiet time, since he will achieve a much higher profit with it than by selling the pieces, which are probably also very well paid for (1928). With the Persianer, practically every part, no matter how small, is recycled into bodies, and sorting is relatively uncomplicated due to the curly structure. For the Persian claw bodies, curly pieces were often also processed in order to achieve a nicer effect similar to the broad-tailed Persian, at the same time it made the price of the more expensive claws cheaper. Occasionally the non-moiré tips of the claws were chopped off and processed into bodies with a very low rating. The curly legs are knocked off and often come with the Persian piece bodies. The most popular bodies are usually those made from Persian claws, the heaviest are the Persian head piece bodies (heads with necks).

- Shortly before 1955, the GDR began with the series production of Persian claw bodies, after trade contracts for the delivery of fine fur skins had been concluded with the Soviet Union in 1951 . The ready-made parts manufactured by VEB Pelzbekleidung Delitzsch differed from the panels manufactured in Greece, for example. The claws were sorted into right and left as well as into the different, also different black, color refinements. The claws were then moistened and stretched out the next day, the ideal size should be 3 by 15 centimeters. As with the fur sorting, a preliminary and a fine range were created. About two to four kilograms of claws were needed for a body. In the pre-range, a distinction was made between smooth and moiré claws, but above all in seven different hair length differences (smoking differences), extremely flat ones were not suitable for processing. During the fine sorting, the claws were placed one behind the other on cardboard for the seamstress and sorted. The flat side was placed against a recorded line. Up to a strip width of seven to eight centimeters, the claws on the smokier, more curly side were supplemented with fur remnants. The claws were edged with the skinning knife and the pieces adjusted. After sewing a ribbon about 36 meters long was created. These stripes enabled individual adaptation to the respective pattern, lengthways, crossways, parquet and diagonal processing were possible. Such work was awarded a gold medal in 1981 at the International Fur Congress in Liptovský Mikuláš , Hungary.

Dyed Persian claw coat with fox piece collar. The otherwise always falling Persian thieves were also processed (2010)

- Pechaniki , pieces of pechaniki, like marbles, provide material for fur linings (1928).

- Reindeer, caribou, pijiki , the leg parts are used a lot by the natives of the far north for footwear and trimmings, the hair is less brittle than the longer-haired torso of the adult reindeer.

Seamstress with a kamik (Eskimos boots) made of fabric, sealskin and caribou boneskin (1999)

Handicraft bag of the Khanty , Siberia, made of reindeer skin headpieces (2009)

- Sheepskins , good pieces, are highly paid for, and in Russia they are mainly assembled to trim hats (1911). They are sewn together to form bodies that are processed into jackets, foot baskets and other items, from already velouted or napped pieces with the leather side facing out.

- Swan , swan pieces are used as trimmings for ball toilets and light clothing as so-called swan brews (1928).

- Seals , Seal Skins malice are well paid and in England the smallest pieces composed still caps, etc. (1911). Due to the oval shape of the fur and the fin holes located far in the fur, large residues are left over when processing all types of seal fur. The use of these parts for clothing purposes turns out to be difficult, mainly shoes, bags, mosaic carpets, animal figures and the like are made from them. The commercial importation of certain goods made from juveniles of the harp seal (whitecoat) or the hooded seal (blueback) into the territory of the Community is now prohibited under Council Directive 83/129 / EEC of March 28, 1983, for the current status see → Seal skin .

Inuit, seal on the left, caribou on the right , using pieces of fur from the same material (1999)

- Sea otters , good pieces, were highly paid for, and in Russia they were mainly put together to fill hats (1911). In 1911 an agreement, the "Convention for the Protection of Seals", was made to avert the danger of the sea otters becoming completely extinct. The skins have not been on the market for a long time.

- Skunks , The skunks ' tails are to be put together to form durable templates by placing sides of black-colored scales (raccoons) between them at the bottom (1885). Often around two thirds of the skunk's tails have already been removed from the raw fur in order to use this particularly bristle part of the tail for the brush industry. Far better paid than the tails from Streifenskunk were those from Fleckenskunk, because his particularly straight hair did not tend to twist like a corkscrew (1936). The best skunks are completely black, then they become smaller and more difficult to work with because of the smaller or larger fork-shaped white and yellow markings that have to be cut out, even if the cunning tobacco shop, as is the case with smaller forks, already scissors the white had them cut out and in this way put bald spots in the place of the white stripes, which are covered by the hair and are less noticeable (1911). The white forks, which were not trimmed by the “smart tobacco shop”, were cut out by the furrier and put together into strips and then dyed dark by the tobacco company. It was used to make fur lining, muff leaves or "tails". Apart from the fact that the skunks fur is no longer an essential article in the fur industry, as it was until after the 1920s, the decorative white fork is now always left in the fur during processing. You work the heads together in order to make trimmings or trimmings from them again. The black and white heads, put together in a star shape, create a pretty design for blankets (1928).

- Raccoon (scales) . The tails are particularly sought after for holiday hats for Polish and Galician Jews (1885). Smoky sides are put together to make sleeves, even fur linings, heads are trimmed in front of black furs with scales, the tails are permanently trimmed (1911). Good sides are put together to form bodies, the tails are popular pendants for key rings and other items.

- Wolf , waste from wolf, at least the larger ones, can at most be used for foot pockets or hunting muff food, smaller waste is worthless (1885). Wolf pieces are twisted into tails (1928).

- Kids , goat waste , goat waste are bought from brush makers (1911). Kid's claws are made into plates in China.

- Sable , the remains of these precious skins have always been carefully used. For the second half of the 17th century it is recorded for the city of Archangel ( Arkhangelsk ) that in one year not only 29,160 sable skins but also 18,742 sable tails were exported from there. Apart from the [sable skins] sold individually and in pairs, it is the rule that the tails form a special trade item, which is mostly used for so-called boas for women. The hind feet are also sold separately, while the front paws are usually left on the bellows to fill in small gaps when sewing the furs. The neck piece is also often cut off because the rust-colored throat patch would disturb the uniform beauty of the fur. The neck pieces are then divided again by cutting out the throat patch. Two sacks are sewn from 4 - 500 neck pieces, one of which consists of throat patches and the second of the other half (1900).

- The processing corresponds to that of the pieces of mink. The bodies made from the orange-spotted throat pieces (nourkulemi) are livelier than those of the mink, the undesirable, white throat marks have largely been bred away from the mink. The Schtreimel , the eye-catching cap that looks almost the size of a wagon wheel and is mainly worn by married Hasidic Jews, is mostly made from the tails of the so-called Canadian sable or Russian sable tails.

Germany and Austria

Perhaps the oldest mention of the creative use of pieces of fur can be found in Tacitus (* around 58 AD; † around 120). He writes about the Germanic peoples: “They also wear the fur of wild animals, those who live near the shore in a casual manner, further inland in a rather careful selection ... They select the animals and cover the stripped fur with colored pieces of fur from animals that are far away The ocean and the unknown sea ”.

The use of fur leftovers has entered the German fairy tale world with Allerleirauh (the Brothers Grimm initially wrote Allerlei-Rauh), i.e. a variety of tobacco products . The use of the term Allerleirauh is guaranteed until the 16th century. Mainly inner linings, allegedly also trimmings, were made from these fur parts (on the old pictures it is almost never possible to understand whether the fabric part was only occupied at the edges or at least fully lined).

After 1900 only a few Greek fur traders came to the Leipziger Brühl , but a strong Greek colony had now settled in the area. The upper class traded fur with the Balkans, Turkey, America, England, France, etc. The second consisted of small traders who manufactured cheap articles in Leipzig, mainly pieces of fur. For example, the manufacture of imitation ermine tails, skunks tails and certain fur linings were entirely in their hands. During this time Leipzig supplied the entire world market with frog tails and fox tails. The strong competition from Berlin that existed in the 1870s and 1880s had meanwhile ceased, only the production of goat tails, the use of which is probably no longer clear to us today (as a feather duster?), Was still carried out in Berlin.

The fur processor simply threw the pieces away. The pieces dealers first had to inform the owners of the furrier workshops that the collected rubbish had a monetary value, all the more so if the pieces were sorted according to their type. “That was apprentice work every evening. This rubbish soon accumulated in boxes and sacks and the Greeks came, appraised and weighed, paid in cash, and something else fell off for the apprentice, ”said Philipp Manes.

In the past, foxes in particular were bought in Leipzig, the back and tails of which were cut off and the paws cut off and traded in Leipzig, as the fox bellies were mainly in demand in the Orient. Around 1911, when trade with the Balkans slackened, many pieces of fur were still imported to Leipzig, especially the noble fur sable, lynx, mink and chinchilla , which were carefully sorted and put together into well-made food.

Foxtail boas were a preferred fashion item at this time, and tobacco retailer Emil Brass prides himself on the fact that his father M. Brass had the first boas made from foxtail in Berlin in 1874, followed soon after by the Leipzig company Apfel.

Particularly in the period after the Second World War, coats made of Sealkaninseiten were usually worked “in reflex” (today called “up and down”, hair direction alternating up and down). Likewise, large-scale clothing was made from marble sides, with an artificial grunt , the darker middle of the fur, sprayed onto the body . From foal waste and especially the claws cheap coats were made. Later on, wildcat and ocelot sides also made quite acceptable pieces of fur when put together well. After the Second World War, the fur leftovers in the German and Austrian workshops were also processed in-house in the summer months when there was little work, especially the relatively large Persian claws, which therefore took up less working time. Persian claw coats made up a significant share of sales not only in department stores but also in fur retailers. Very quickly, however, with the German economic miracle, the workshops were fully utilized and the wages were so high that it was more economical to export all items to Greece.

Before the furrier prepares the garbage for the piece dealer, the pieces suitable for repair work are sorted out and stored, sometimes for decades. The leftovers to be returned, referred to in an Austrian fur lexicon in 1949 as “so-called furrier manure”, are separated according to the type of fur before they are collected. The more precisely the furrier pre-sorts the pieces according to color and fur parts, the better the price per kilo that can be achieved. The leftovers that arise in the manufacture are usually of higher quality than those from the detailed skinning, since the focus there is on fast, and not to the same extent on material-saving, work. Especially in Greek workshops, when trimming the skins, care is often taken to ensure that the pieces are as large as possible and are not cut up unnecessarily. For example, the paw pairs can be removed together as long as the peeled fur has not yet been cut. Bodysuits made from these larger parts require less working time and result in a more effective pattern.

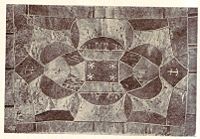

Mosaic work

The real beginning and the boom of modern, now almost forgotten, mosaic work was in the 1850s and flourished between 1870 and 1890. The beginnings of artistic fur mosaics were in Vienna. Here they were particularly well cared for and achieved world renown as a Viennese specialty.

In this work, the rational and as complete use of the fur residues as possible was not necessarily in the foreground - ultimately, almost the entire processing of pieces of fur is to be regarded as mosaic work - but rather the artistic execution. Mainly covers for foot baskets, footstools, pillows, hunting muffs and ladies' beret sets were made, but also decorations for coats and decorative carpets.

Several tasteful works were shown at the World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873 and at other trade and specialist exhibitions. After the article went on sale at the Leipzig trade fair, imitators were soon found in other countries too, but the reputation and success as an export article remained with the Viennese furriers. One of the main sales areas for mosaics around 1900 was Russia. In 1936 a special fur picture was mentioned again, made by the English company L. Mitchel. The 91 × 137 cm work showed the passenger ship Queen Mary . The edge was made of light and dark broad-tailed , the sky and the sea of dyed rabbit fur in realistic shades. The hull was made of Seal and the chimneys of red-colored lamb , the smoke of mole skins .

The work itself was decried as ungrateful in the industry, the yield, especially for exclusive one-off pieces, probably almost never justified the effort, the artistic endeavors of some particularly talented furriers were in the foreground. The works, which often require months of work, are also not permanent. Natural aging and fading from light soon make them less conspicuous and destroy them in a few decades. Unfortunately, this also means that hardly anything is left of it today. A few, more or a few good prints of old photos still bear witness to this art.

In preparation for a mosaic, a drawing was made that showed the picture down to the smallest detail. In general, a dark background was chosen on which figures such as leaves, animals or people were slightly shaded. These were mostly made from otter skin. The parts cut out with the skinning knife were trimmed in the hair with scissors, so that a slight relief was created in the manner of sculpture. The different colors of the upper and lower hair allow special effects to be achieved. The ears of martens, foxes, etc., which are otherwise rarely used in skinning, were also used to produce flowers. Seal fur, colored or natural, is particularly suitable, the tight hair results in a clearly defined pattern. Larger figures were sewn into the ground, smaller ones simply put on. The eyes were mostly glass eyes or pearls, cords and embroidery were also integrated.

The art of fur mosaic is not extinct today. In particular from China with its old furrier tradition and from the rest of Asia there are very beautiful works, carpets, rugs, wall hangings and everyday objects with ornaments or figurative pictures, often with images of animals. A popular material is cowhide ("bull skin"). Fur mosaics, often made from antelope fur, also come from Africa. The playful craftsmanship of the work of the time probably does not match them all, the commercial interest is in the foreground, and the taste of the time has changed. Nevertheless, they are often very elaborately made and occasionally even sewn by hand. According to our European standards, this work is still mostly inappropriately poorly paid today due to the wage gap with the producing countries.

- Mosaic work, around 1900

Main material partly colored lambskin, dog fur , leopard fur , lambskin of various colors and smoke (A. Goldschmiedt, Vienna)

Poland

A reporter from the fur industry who was killed by the Nazis in 1944 in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp , Philipp Manes (* 1875 - † 1944), found the performance that was spent in Poland to be almost even harder and more sweaty than the work in Greece described below . Although at least he has probably never traveled to the Greek fur-processing locations himself. In the area around Krakow a special industry had spread that made tablets from the rubbish of Persian processing, heads, pieces and claws, at home, often including the youngest children. Very large quantities of the products were traded through Berlin.

The best Persian piece plates cost 34 to 36 marks in the 1930s, and head piece plates 16 to 22 marks. Claw panels were less available because the furriers did not give up their paws, but rather processed them themselves during the so-called quiet time. They brought in 45 marks in the finest quality. The fabric confectioners liked to buy Persian goods because they could be used as a good trim material and looked very elegant, especially the best piece and head plates.

Apparently this Polish branch of industry ended in the time of the Second World War , nothing is known about it since then.

Southeast Europe

In the past, most of the furriers in the Balkans limited themselves mainly to the production of fur lining, the ideal use for fur scraps. They had shown extraordinary skill in this. The main principle was production at the lowest possible price. The purchasing power of the general population was low and the competition was enormous. Even the smallest pieces of fur found a use somehow. Not even the thread was bought ready-made, but turned from raw cotton by the apprentices.

Originally, most of the people involved in skinning were Ottoman Turks, but soon they were pushed into the background by the ever-expanding Greeks. However, the furriers' guild has always been very respected. For a long time the members of the Greek Ypsilantis were at the forefront of this furrier guild, among whom the dignity of the great furrier was inherited. The Ypsilanti are an important Greek-Phanariotic princely family, which is documented until 1064, originally came from Trapezunt (Turkish Trabzon), later mainly resided in Constantinople and whose members held high state offices in the Ottoman Empire as well as in independent Greece clothed. The fur trader Emil Brass wrote in 1911: "Today the Ypsilantis belong to the Romanian aristocracy and probably don't like to remember their ancestors who used pliers and needles".

The furrier shops in the cities of the Balkans were furnished in the oriental style. They had neither windows nor doors, the floor was covered with straw mats on which the master (Ussta) and the workers (Kalfas) sat. On the shelves on the walls lay the fur linings, piled up in batches, which were spread out to the customers on the raised floor in front of the shop. The lining, laid out in the same way by the buyer, was measured and cut in the presence of the suspicious customer. The lining was then more simply pinned in than sewn in; You didn't know hair seams and the warping on the sides. A simple pocket knife was used as a tool .

The retrospective of 1936 continues: Most of the assistants were Romanians or Greeks who peddled furrier goods on the streets in the winter, some of them on their own account. They wore sleeves lined up on ropes, and cheap fur lining in large wraps. With the lowest living needs and expenses, they became dangerous competition for the local furriers. With a few pennies saved and starved, they probably rented a shop and thus increased the masses of poor furriers .

Every autumn, Tartar traders also came to the cities of Turkey with cheap Russian fur linings. They walked in their striking national costume , carried rabbit food over their arms , made of yellow-colored dewlaps, black cat food , saddlebacks and feudal dewlaps . They cried out loudly through the streets, offering their goods at constantly changing prices.

With the revolution in transport, the offering of fur goods by traveling around ended; at the same time machine work came up and fur lining production disappeared from southeast Europe, except in the Kastoria region .

Kastoria and Siatista

Whenever the fur industry talks about piece processing, it is usually synonymous with Kastoria , the Greek city near Albania. The second, smaller, 50 kilometers away, also involved in the sewing of fur pieces, Siatista is only known to a few. At the 4th International Fur Fair in Saloniki in 1976, only twelve of the 79 Greek exhibitors came from Kastoria City, while 21 came from Argos Orestiko (located in the regional district, Kastoria prefecture) and 29 from Siatista. But Kastoria is also hardly known outside of the fur industry. In the 1980s, a large textile company, the largest German fur supplier at the time, forbade any reference to the Greek origin of its orders.

The fur leftovers, which are first and foremost waste products for the "normal" furrier, used to be the basic material for the Castorian furriers since the end of the Second World War.

What Kastoria has in common with the fur processors from Ochrida, discussed below, is that it was under Bulgarian rule for a time, before 1018, and belonged to the Ottoman Empire until 1912 . The place name suggests a fur animal, Castor, the beaver, who probably lived here in the past. However, the derivation from Zeussohn Kastor is also quite likely. By the end of the 1950s, Kastoria had 8,000 inhabitants, in 1971 the number had doubled, and in 2010 it was already 37,000. This development is due to the city's one-sided fur industry-oriented economy. The boom in fur sales, especially in the post-war Federal Republic, led to an unusual economic expansion in Greece. The number of fur factories was around 2000 in 1972. In 1988 the total number of workshops in the areas in and around Kastoria and Siatista was given as 5000, which together employed 15,000 people. Around 80 percent of the people working in industry and trade in Kastoria County, an otherwise agricultural and forestry area, were employed in the fur industry in 1978.

It is believed that furring began in Kastoria under Turkish occupation in the 15th century. Until the end of the 16th century, the Kastorias furriers obtained their raw materials from Turkish markets. Around this time they came into contact with other European peoples and began to import materials from Germany, Great Britain and France, later they also imported pieces of fur from the USA and Canada. When the sultan issued a decree in 1713 that forbade non-Turks to wear fur because a shortage had occurred, the furriers in Kastoria began to use the fur leftovers , which they now call commatiasta . It is unclear whether they developed this art themselves or whether they adopted it from Constantinople or Romania. For Siatista, the beginning of skinning is given as the 16th century.

In the German-speaking fur industry, in connection with fur processing in Greece, Kastoria is always spoken of, whereby the city of Kastoria is usually meant. At the 4th International Fur Fair in Saloniki in 1976, 29 of the 79 Greek exhibitors came from Siatista, 21 from Argos Orestiko and only 12 from Kastoria City.

A German furrier describes the conditions in Kastoria at the beginning of 1900:

- “ In this mountainous district, almost all of the residents are furriers in addition to their agricultural work. However, all of her skill lies in handling the pieces. Some of these furriers even travel to the European fur markets to buy fur leftovers by the kilo. At home, the father of the family sits in the living room, sorts and cuts the pieces, often no more than 1 cm in size, with a bread knife and places them in squares on pieces of paper the size of a hand. The other family members do the sewing. Putting these pieces together to make larger ones is again a matter for the master. In autumn, the finished linings are provided with fabric underlays and the hair side is decorated with colorful ribbons to cover particularly bad areas and to enhance their appearance. So they are brought to the larger cities, especially Constantinople , and sold there in the magazines or offered on the streets. Such ambulant furriers announce their arrival with the exclamation: 'Kürktschi', or (Greek) 'o gunaris'; they carry the food openly, or in a wrap on their back, and go into the houses to work. "

Since 1939 it was legally stipulated that only companies based in Kastoria or Siatista were allowed to import fur scraps into Greece. Constant contact with the fur markets such as Leipzig, London and Damascus and, most recently, the tax exemption granted in 1951 for the import of fur scraps were decisive for the continued success of fur scraps. This also applied to hides, only here on the condition that they were exported within a certain period of time after processing. The Greek state only granted this privilege to the two towns of Kastoria and Siatista. Furthermore, the companies were allowed to keep part of their income abroad in order to buy new items. Later two villages in the district were added, all others had to pay 25 percent of the value to the state. Another preference was the reduced, roughly one-third lower contribution of fur workers to social security. A disadvantage was the elimination of the premiums otherwise paid for fur exports from Kastoria.

In 1978, at the peak of western post-war fur fashion , Leonidas Pouliopoulos described the situation in Kastoria at that time: “ The work of the Castorians is divided into two main parts: 1. The production of bodies from mink, Persian and other fur waste. 2. The manufacture of coats, jackets and paletots mainly from mink and Persian fur in wage labor. The processing of fur leftovers (fur waste) is still the main activity today, which is largely done for the local companies' own account. “The leftovers came from different European countries, for example Austria or Denmark. But since the center of the fur industry was Frankfurt am Main, all leftovers went to there, from where they were transported on to Kastoria in trucks. In the opposite direction, up to 100 large shipments of semi-finished products and made-up made of pieces and skins drove daily, mainly to Germany, here it was about 5000 kilograms a day.

By the time the fur sewing machine was introduced, around half a dozen oligarchs had divided the market among themselves. As early as the middle of the 19th century, they occupied the various raw material markets such as Amsterdam, St. Petersburg, London and Leipzig and then had the pieces of fur assembled in their homeland as wage labor. In 1988, a member of the Pouliopoulos family of fur sewers still remembers how his aunt, who was married in America, came once a year with her Rolls-Royce over the donkey slopes to Kastoria to check on the family's well-being. The increase in industry since the 1950s by no means led to an expansion of the companies; on the contrary, many of the large firms dissolved. In 1969 there were still around 40 large companies in Kastoria, each with 100 to 250 employees. In the smaller family businesses that were constantly being founded, many family members who did not belong to the close family often worked. Especially young men were occupied with the physically as well as physically strenuous, unsustainable fur sewing on a piecework basis. Fur sewers were only young people, there were only a few over 30 years old, hardly anyone was over 40 years old. The employment relationships rarely corresponded to the norms customary in Germany. The lighting was often poor, even in the newly built concrete skyscrapers there were almost no break rooms, and people ate at work. The air conditioning, which is absolutely necessary in the summer months, was not available and everyone suffered from the heat. The daily working time was eight to twelve hours, break regulations were unknown, there was usually only one long break at lunchtime. People were happy when they managed to get through the time as a fur sewer without harming their health. Nevertheless, there was hardly any dissatisfaction due to the personal ties, everyone tried to earn as much money as possible. Since skinning is a seasonal trade, the time between the seasons offered some relaxation. The work of the purpose (Michanikos) who exciting the bodies required a little less concentration , it was due to the work intensity behind the fur sewer (Stamatotas). This was followed by the sorter (Chromatistas) or the cutter (Kophtas). The interior processing of prefabricated parts, such as pricking, feeding, etc. was a decidedly female work. Only a few seamstresses initially acquired all of these skills, so that they could later be employed as full-fledged furriers or become self-employed as such. Beginning with Persian fashion and the associated increase in orders for furs made from whole skins, a change occurred here over the years.

The most unpleasant jobs were often assigned to work from home, and children between the ages of eight and ten often contributed significantly to the family income. For a small fee they sewed the small and very small pieces together. Even professionals from outside the industry, even postmen and fishermen, sorted pieces of fur after work or sat down at the fur sewing machine.

Attending the vocational school, which had existed since around 1958, was not compulsory, the entire technical training took place in the company (1978).

At the beginning of the 1950s, protracted disputes began for years over the question of whether the Castorians were also allowed to process skins. Mention is made of a strike by "opponents of fur processing" in 1963, after which it was not until 1964 that whole fur was allowed to be processed in Kastoria under the supervision of the customs office. This privilege was reserved only for the city of Kastoria - in contrast to the piece processing, which was occupied by almost the entire province of Kastoria - and the province of Siatista. In 1976, the income from this non-piece processing, with which about ten percent of the companies were involved, made twelve percent of the total export value.

Often the remnants of the skin processing remained with the companies and thus represented a part of their income, with foreign contracts it was the rule that the pieces remained.

Around 1976 the value of fur remnants imported annually amounted to 17 million US dollars, about a fifth of the export value. The value of the 83,000 kg of leftover fur in Kastoria itself was 92 million drachmas (2.5 million dollars).

In the mid-1950s, A. Gannis described the free market economy of Kastoria as “primitive” liberalism with which entrepreneurs harm themselves. Attempts have been made again and again to influence the purchase prices through agreements between the buyers on site (purchase cartel ). As an example of the disagreement among fur traders, it is reported that five or six fur traders banded together in order to buy fur scraps in New York not above an agreed price (the annual sales of the American fur companies for all waste averaged one million dollars a year before 1949) . When the selected representative came to the New York market, he found that members of the interest group had already reserved the goods at a price higher than the agreed price. The same competitive dumping is also recorded for the fur factories, especially for the wage laborers. - The fur clothing exported to America from Kastoria consisted of 98 percent pieces of fur around 1980.

As early as the mid-1950s there was information that other countries could compete with Kastoria with piece processing. Israel was named as the first country, but it only developed into a specialist in processing Persian broadtail pelts. Later there was information about France, where companies with the Greek name were advertising Greek piece goods in Paris, about Italy, the Federal Republic and Belgium. It was probably the high wage level in these countries that ultimately made this fail. The attempt at that time to spread the processing of pieces of skin in Latin America does not seem to have been successful either. Towards the end of the 20th century, however, the more lucrative and, in some cases, less labor-intensive clothing production from whole skins in Kastoria had reached such an extent that large local companies no longer had the fur scraps processed at home, but sold them to China. The number of people employed in the fur industry in the prefecture of Kastoria and Siatista is still significant, but it has decreased significantly (as of 2014).

Furriers Kastorias and Siatistas not only had business relationships with all countries of the world relevant to the purchase and sale of fur scraps, they also founded their own companies in many countries. From Siatista alone there are said to be 200 large companies in Western Europe that trade in fur products from their homeland. Many established themselves in then wealthy Austria. At the beginning of the 19th century, at a time of many wars and civil wars, many emigrated to the USA, where they also successfully settled as furriers. After the Second World War, many went again to West Germany, France, Canada and the USA, from where they continued to maintain close contact with their homeland. Around 1969 there were around 4,000 Castorians in New York alone, and 2,000 in Germany.

The furrier businesses and the individual furriers were organized in the following associations in 1972:

- Furrier Society "Prophet Elias"

- Agricultural credit union for fur production SPAG

- National furrier association (mainly small one-man businesses)

- National Association of the Fur Garment Industry "Prophet Elias"

- The Association of Fur Crafters

There is also the national fur workers' association (Ethniki Gounergatiki Enosis) founded in 1924, which is subordinate to the general union federation for workers.

The patron saint of the Greek Orthodox members of the fur industry is Saint Elias . In 1900 Totchkoff affirmed about the furriers in Ochrida: “ ... every furrier still believes stiffly and firmly in the ancient legend handed down to him by his ancestors that Elias was the first to wear a fur coat and that he wore this coat, when he himself went to heaven, leaving his pupil Elisei behind, but the latter performed miracles with the cloak. The custom, reminiscent of the old house cooperative, still exists today that on Eliastage the master entertains his journeymen and apprentices ". Even in the newly created fur center around Niddastraße in Frankfurt am Main, the autumn ball of the association of Greek fur traders and wage-fryers "Prophet Elias" was a social event not only for the Greek industry members after the Second World War until after 2000 .

| Import of fur scraps in 1976 Value in drachmas (36 drachmas = 1 US dollar) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| countries | Fur remnants | countries | Fur remnants | countries | Fur remnants | countries | Fur remnants | |||

| FRG | 430.813.801 | England | 16,717,475 | Hong Kong | 3,588,625 | Australia | 77,824 | |||

| United States | 109,571,284 | Switzerland | 13,499,750 | Spain | 428.206 | Belgium | 75.281 | |||

| Canada | 23,470,045 | Japan | 5,444,337 | Sweden | 318.980 | Turkey | 26,381 | |||

| Italy | 23,346,128 | France | 4,089,034 | Malta | 223.266 | |||||

Sales in the fur industry have always been subject to exceptionally large fluctuations. The entrepreneurial risk is high because of the expensive warehousing, with finished clothing there is not only the risk that the type of coat or color will be in demand in the coming season, but also that the parts may be out of date. The fur sales are not only dependent on the general economic situation, fashion and the respective winter weather play a very decisive role. The fashion risk was still low in the first few years after the Second World War, when the fur industry was essentially a supplier market and textile fashion only partially participated, fur fashion was considered timeless. The risk did not only affect the business owners, if there were no orders, the employees were at least out of work during the so-called quiet time.

In 1966, 390,000 kilograms of processed mink pieces were exported from Kastoria, their value was around 560 million drachmas. A temporary fur lull caused exports to drop to 360,000 kilos in the coming year, at a value of 430 million drachmas. The year 1968 brought a mighty upswing with already 430,000 kilos and well over 600 million drachmas. The weight of a coat body was given as 1.7 kilograms, but even within one type of fur, the weight difference between the different parts of the fur is considerable. The average price for bodies made from mink remnants was $ 180 to $ 240 in 1969, top quality was more expensive.

In 1978 Pouliopoulus thought it possible that Kastoria might have the highest daily wages in Greece. The statutory minimum wages at the time were (1 DM = 16 drachmas):

- 1. Professionals

- a) Men 385 (married 405)

- b) women 345

- 2. Others

- Men 260 (after 6 months 270)

- Women 245 (after 6 months 255)

- 3. Apprentices

- both sexes 155 (after 6 months 175)

The piecework and daily wages were estimated in 1976 for the various specialized agencies of the Castorian fur workers as follows:

1) Fur workers who deal with the processing of whole skins:

- a) fur sewers (piece rate, 60 drachmas per strip of mink); highly qualified 800 to 900 drachmas

- b) Sorter (daily wage) 1200 to 1700 drachmas

- c) Furs (piece wages, 250 drachmas each), 900 to 1300 drachmas

- d) Women (staffing, pricking, feeding) 400 to 600 drachmas

2) Fur workers who dealt with the processing of fur pelts (fur residues):

- a) fur sewers (daily wages); highly qualified 500 to 700 drachmas, well qualified 300 to 500 drachmas

- b) Sorter (daily wage) 600 to 800 drachmas

- c) Purpose (daily wage) 600 to 800 drachmas

- Branch Persian Claws:

- a) Fur sewers (piecework wages) approx. 600 drachmas

- b) cutter (piecework wages) approx. 600 drachmas

- c) Purpose (daily wage) 400 to 500 drachmas

Most of the fur workers were engaged in the above activities. In other branches wages were around 500 drachmas in 1976. Contrary to the statement that the Castorians are the top earners in Greece, it was also established at the same time that the fur worker is generally not a well-paid worker , considering that skinning is a seasonal trade and one cannot be busy all year round and that the performance of fur workers decreases the older they get (e.g. fur sewers or sorters, whose eyesight becomes weaker over time).

Around 2000 there were around 120 fur shops in the small Greek seaside resort of Paralia (Katerini) , 195 kilometers east of Kastoria, most of them probably branches of the Castorian furriers. According to a study provided by IEES Abe, the Greek textile and clothing industry, fur is still number one in the export sector in western Macedonia (2012), despite falling numbers.

In the vicinity of the Castorian fur breeders' farms there is a "bio-processing plant" that processes farm waste into electricity and other resources. As of 2019

Processing in Kastoria and Siatista

Around 1969 the leftover fur arrived in Kastoria in bales of three hundredweight each. The sorting department of a medium-sized company managed to sort three to four of them every day, despite the huge number of pieces pressed in it. At the time, a body made from the flat mink front claws fetched $ 230, the rear claw bodies were considerably cheaper. Bodies made from the heavy headers cost about $ 100, and the resulting side pieces of the standard brown mink cost about $ 130. If the center piece was cut out of the side pieces and processed separately, 160 to 170 dollars were achieved for it. Back pieces were hardly for sale, although they come from the actual core pieces of the mink fur, they do not make a nice picture.

Some companies specialize in certain items. Mink headpieces are the easiest to work with, around 25 workers doing 10 bodies a day. In companies in which the work was more “contemplative”, 90 people were needed for the same number of items.

Separating the different parts of the fur is only the first step in sorting. The division into different colors usually takes place in the countries of origin in order to have a simpler assessment basis for resale. Nevertheless, there are often many different mutation colors in a sack or bale. The standard mink alone is divided into 12 different shades of color. Good mink paws are usually sorted into up to four hair length and eight basic color levels and six sub-colors each. Strictly speaking, there are 360 to 400 sorting options, a process that can only be managed in several work steps. Then the pieces are sewn into strips, these are sorted again and then put together. The mink tails mostly remained in the fur-processing countries, where they were mainly made into collars and hats.

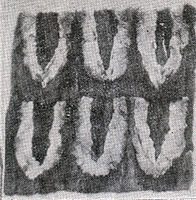

Bodies are normally only sewn together from the same pieces of fur, for example only from head pieces or only from tails. This results in uniform patterns such as herringbone or zigzag (English chevron), basket weave, horizontal or transverse pattern or wave or scale pattern (English scallop). Oval side pieces are worked in a less even or random arrangement (English random). Combinations of these patterns or different colors are also produced. All designs from the textile sector are also offered, such as stripes, houndstooth, checks, rhombuses, etc. The bodies are partly sheared, printed and dyed in all fashion colors. The pieces of skins that have already been plucked or sheared are also processed (pieces of velvet mink). Particularly light reversible furs can be made by napping the leather side.

Rare colors that are difficult to get enough of tend to fetch the top prices. For a front paw body made of sapphire or tourmaline mink, $ 260 to $ 280 was paid at the time.

Ohrid (Ochrida)

Ohrid ( Greek Αχρίδα Achrída ) is now a city in western North Macedonia , near Albania . The distance to the Greek fur trading and processing center Kastoria is only 140 kilometers by road, at the beginning of the 19th century the bishop of Kastoria was subordinate to the archbishop in Ohrid . Until the conquest by the Serbian army on November 29, 1912, Ohrid, then called Ochrida by the Greeks , belonged to the Turkish Empire for over 500 years. From 1946 to 1991 Macedonia was a republic of Yugoslavia . In 2002, with 42,000 inhabitants, it was the eighth largest Macedonian city, in the end of the Turkish era, which is discussed here, there were 13,000.

Skinning has always been the leading trade in Ochrida. The Ochridans traveled to other countries with their goods early on, especially the trade fair city of Leipzig. Although they were pure Bulgarians, as Turkish subjects they were not allowed to call themselves that, they were referred to there as “Greeks” according to their “Greek” -orthodox creed. The main business partners in Leipzig were the Constantin Pappa bank (commission business), the G. Keskari company originally based in Ochrida , whose successors are still active in the fur industry today, and the Kyoopoulos commission and sales business. At that time, these three companies were supplying almost the whole of the Orient with the necessary raw materials.

In the days when the transport system was still inadequate, the Usundjowa trade fair ( Usundschowo (Узунджово)) was of great importance for the sale of goods from Okhrida. A myriad of traders came to the place in southern Bulgaria , in the district of Chaskoi (Oblast Chaskowo, Okrug Chaskowo) on the road from Philippopel to Adrianople , even from the Occident . The Ochridans who came by horse and cart were the main suppliers of furs. The main buyers were the Turks, for whom there was no self-production at all. Occasionally not everything was sold, so people moved on to the Turkish cities and tried to sell the rest by selling them in inns and peddling every now and then. The furriers from Ochrida were not the only suppliers, it happened that up to 400 masters and journeymen in the hinterland of Saloniki spent most of the winter selling their products. With the construction of the railways and the penetration of foreign competition, this form of trade ended. In 1876, two years after the construction of the Rumelian Railway, the market in Usundjowa was closed.

When large-scale industry moved into the fur branch in western Europe with the fur sewing machine around 1900, the furriers in Ochrida in Turkey and Bulgaria were still working in the traditional, laborious way. The small master craftsmen did not have the capital for costly new acquisitions, and the larger trading houses missed the necessary expansion to keep up with the West, but also with the competition in Kastoria. To make matters worse, the Turks, who had previously been the main buyers of the goods from Ochrida, began to dress in western fashion. Up until then, the highest military and civilian officials viewed it as an elegant means of clothing and preferred to use it . It did not succeed in establishing itself in the emerging, large customer market, fur clothing for women. In addition to the lack of capital, the political situation and the lack of feeling for the new western fashion did the rest.

While around 1875 there were still 150 independent companies with 800 male employees, 25 years later there were only six, two larger and four smaller ones. The larger firms employed 50 to 60 workers in the summer and only 30 to 40 workers in the winter, usually in the workshops themselves, only in exceptional cases working from home. At that time, home work was only carried out by poorer family businesses on a piece-wage basis, with the whole family working together. At that time there were 48 foremen, 74 journeymen and 18 apprentices in these companies. Payment was based on the daily wage, the master received 15 to 20 piastres, depending on his level of skill, a journeyman [“ 10, 5 ”] (unclear) and the apprentice 1½ piastres a day. The free meals that were common in the past have now ceased to exist. There was no specialization in certain types of fur or pieces. Due to the decline of the industry in Ochrida and the otherwise poor economic situation in Turkey, the workforce emigrated en masse, some of the remaining furriers devoted themselves to the local agriculture and the vineyards, which were strengthened again as a result. The final decline of the once powerful craft there was unstoppable.

Processing of the mink, skunks and cat pieces in Ochrida

In 1900, D. Totchkoff, originally from Ochrida, wrote in his doctoral thesis “Studies on the tobacco trade and skinning, especially in Ochrida” for the University of Heidelberg on the use of pieces of mink, skunks and cats:

“ A skilful master and specialist - because only such a person can dare to do this work - sorts z. B. a batch of sable pieces in 12 assortments. From these, each range is classified according to beauty, delicacy and color. With the hair side turned outwards, these sorted pieces are arranged in a square shape. These pieces are then carefully turned over by the Krojatzsch and sewn together by the Schiatsch. Sewing these pieces together, often only two to five millimeters in size, is an extremely tedious and time-consuming job. These square-shaped pieces are put together and sewn into a larger piece, a tulum, in the manner of a fox skin (see next chapter) . The finished tulum is washed and dried. The soaking is repeated several times in order to increase the elasticity of the leather of the skin, and finally the skin is dried on a large wooden plate. A trapezoidal shape is measured on this plate, onto which the skin is tipped with closely spaced wire pins. After drying, the fur is patted and combed and is then ready for use, i. H. able to be used as part of a garment. The incorporation of the fur in the garment itself, such as. For example, feeding him a skirt, etc., is a matter for a special master, the Kaplamadji. This Kaplamadji, who receives fur and clothing from the customer for his work, receives z. B. 10 piastres (2 marks). If he does not enjoy the absolute trust of the customer, he is ready to work in his house. In addition to his wages, he usually also receives free board. "

Processing of red fox skins in Ochrida

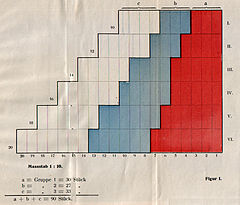

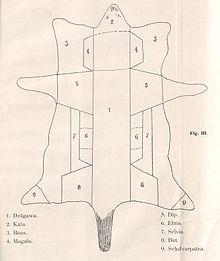

The main article in Ochrida was the native red fox fur. In Eastern Europe at that time it was still customary to use the different parts of the fur separately for certain types of fur. The backs were first cut out of the red fox skins and divided into three parts according to the fineness of the hair. These pieces were again sorted into three groups: The first group contained the best, reddish pieces with the best hair growth. The second the somewhat inferior quality and the third the relatively inferior. The parts were then sorted in the shape of a trapezoid (see picture 1), a job that only a skilled and knowledgeable master could do.