Feh (clothes)

Feh refers to the gray winter fur with a white belly side of the squirrel used for clothing purposes, especially that of the eastern (Siberian) subspecies.

Furs from other regions with the same character and appearance - thick fur with a gray back and white belly - are usually also offered to the end user as faux fur. Red-brown or other different variants should be named with their traditional name, for example "Canadian Feh". The processing of the back skin and the peritoneum skin (dewlap) is usually carried out separately, as a rule they come to the wholesaler already pre-made into bars.

Squirrel skins, especially gray and white Nordic countries, were a highly valued tobacco product not only in the Middle Ages . In times of dress codes it was a fur reserved for the nobility and dignitaries. When animal fur is divided into the fineness classes silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the particularly soft squirrel hair is classified as silky .

Squirrel hair is also made into fine brushes under the name squirrel hair . The tail, technically "tail", is used by Russian and Canadian squirrels. Squirrel hair brushes are used, among other things, as rouge and powder brushes, watercolor brushes or as a pin to apply gold leaf . Fruits, twisted by tail twists into more voluptuous tails, were once a common item in the fur industry, from which collars, capes and other small parts were made by furriers and specialized frog tail makers.

In heraldry , the feh, before furrier and ermine , is the most common variant of heraldic fur - see Feh (heraldry) .

designation

The word “Feh”, formerly also “Veh”, goes back to Middle High German vēch , which meant a colorful fur, mainly from squirrels, but also from ermine until the 17th century . The transmission to the Siberian squirrel in particular is early modern. The word is derived from the outdated adjective fech, feh , from Old High German fēh ("colorful, flecked "). In Old French, semantically corresponds to vair , derived from Latin varius ("different"), which is not etymologically related to the German Feh .

Veder referred to what we understand today as fur lining and fur trimmings. When "werk" is mentioned in old documents (which actually means fur), it always means the squirrel skins, that is, Feh. At that time a distinction was made between Rotwerk (summer skins or Feh with red-brown back), Grauwerk and Schwarzwerk (skins with dark gray back). If back and dewlap (peritoneum) were processed in one, the designation Buntwerk was used. The back alone was called Kürsch , Grauwerk , Kleingrau or Kleinspalt . If you put your ears on the middle of the dewlap, it was called Schönwerk . If only work was spoken of, it was always understood to mean squirrel or squirrel. The additional colors green and yellow came about by chance through an oxidation process . The Russian squirrel hunters made the skins durable with a herbal stain which over time turned light gray backs green and white dewlap yellow. For centuries, red and green feh were only permitted to high-ranking people.

False work were imitations mainly made of white or bluish ermine , in contrast to the pure work .

If today the term Feh is used in trade for non-Russian squirrel skins , the origin should also be indicated, e.g. B. American Feh for skins of the North American gray squirrel .

history

One of the oldest pieces of clothing ever found was made of squirrel skin. It was found in the Italian cave of Arene Candide . The man known as the Little Prince , who was buried around 23,000 years ago, was given a fur cloak made of 400 vertical strips of squirrel skins. The 423 tail bones found with were assigned to the cloak.

Another still preserved squirrel fur was found, along with other fur clothing, in the second burial mound ( kurgan ) of Pazyryk in the Altai from the 4th century BC, a coat that was given to a Scythian princess in the grave when she was in her slain husband death had to follow.

As early as the Arab-Norman period (around the 9th to 13th centuries), the feh was one of the most sought-after commercial items alongside the fox fur . The fur jacket played an essential role for the Normans . In old French it was called “une gupe de gris”, also “jupe de gris”, which later became “jupon” and with us “Juppe” or “Joppe” (another word for jacket). The "de gris" means "gray work", in today's French "petit gris", in German misfels.

In earlier times, clothing made from Feh served as a status symbol , in the Middle Ages only the nobility and high dignitaries were allowed to wear Feh (see also the cape of the canon, the Almutia ). French historians ascribe to Thomas de Coucy that he was the first to wear an inner lining made of reddish squirrel fur as a symbol of status. It is said that he threw it over his shield during the First Crusade of 1096. Many other military leaders followed his example, showing Fehfell as a shield or as a banner.

Philip the Tall One used 6,364 squirrel skins to decorate his wardrobe and 1,500 gray skins for a single item of clothing. The high social value attached to fur at that time is illustrated by the accusation of the confessor of King Louis the Saint, Robert de Cerbon (Sorbon), and the reply by Jean de Joinville , in which he invokes his ancestral right to wear fur (Dialog from the memoirs of the noble Lord of Joinville, Senechal of Champagne, 13th century):

“ You are dressed more nobly than the king, because you wear colored work and green, which the king does not. But I answered him: Master Robert, honor your class, I think I am not wrong if I dress in colored work and green, because my father and mother let me have this dress; but you have no right to do so, for you are the son of ignoble people and you do not wear the dress of your father and your mother and you are dressed in a richer cloak like the king himself. "

The characteristic drawing of the colored work, which, along with sable and ermine, was one of the most coveted fur works of the Middle Ages, is the most frequently used symbol in the coats of arms of furriers. In the big cities the furriers were partly specialized, the color makers worked squirrel and ermine fur, the other furriers used the native fur types.

The at times enormous distribution can be seen in the Manessian song manuscript . It shows false lining, false trimmings, headgear, even crowns made of false fur being processed into beautiful work in most of the 138 miniatures depicting people .

Abbess Herrad von Landsberg , a guardian of virtue in the Middle Ages, listed a coat lined with colored feh in her list of objects that seduce sin. "In her eyes it was a great temptation for men and women to leave the path of virtue." In a French novel by Garin le Loherain , which was widely read at the time , one father wrote in his daughter's poetry album: “Wealth alone is not rich in color or in gray. The human heart is worth more than all the gold in a country ”.

In addition to the commercial trappers, trapping was always carried out in larger societies in Siberia, the so-called "Artelj", mainly in winter, the best season for the fur. Appropriately, the tracks in the snow can then also be seen better. The shotgun was also used by the inhabitants for hunting. However, by 1900 it was far from superseding the bow and arrow. This was partly due to the high price of the shotgun, but also to the fact that bows and arrows are more useful for squirrel hunting in some respects: “Aside from being cheap, these primitive hunting devices have the advantage of the forest residents, which should not be underestimated are not frightened and scared away by shooting, the main thing is that the arrow ending in a broad blunt button delivers the prey unharmed into the hands of the hunter by stunning the animal with a safe shot to the head and then killing it. "

In the 1880s, Feh was an outright children's item, especially for sets consisting of Fehmuff, hat and scarf. Only when the material became scarcer with increasing consumption did the faux fur regain its value. The back coat made of heavy, pure material was now viewed as a luxury item, " the most elegant lady wore it ". "Morning pelts" in the form of dressing gowns were also made from gray work, as well as furs and "half furs" for women. In the interior of Russia, the national sleeveless robe for women, the shower greika (ie "soul warmer") was made from it, which was often worn by the middle class in St. Petersburg . In addition, were Eichhorn skins processed, etc. as trimming on caps, collars, clothes and as a lining in furs . After the First World War , the type of skin was “taken off the market due to the high prices” and the furriers who were involved in it had to “make significant changes”. The company JC Keller & Sohn in Weißenfels is named as the first wrongdoing .

Georg Jacob wrote about the non-gray squirrel skins in 1891: “As far as the color is concerned, red squirrels are not sold in our stores; I only saw gray and white (the latter parts of the abdomen of the same animals); Leipzig fur traders get them from Russia ”.

It was not until 1895 that the Leipzig company AB Citroen succeeded in dyeing false skins brown (mink-colored) for production in Germany. Until then, the Lacourbat company (founded in 1860) in Lyon practically had a monopoly on the popular brown color. This success gave the impetus to the development of further fur colors by the German paint industry.

The place of the German malformation (tanning) and Fehtafelfabrikation was Weißenfels until the First World War . Up until the introduction of the fur sewing machine in the first third of the 20th century , almost all working women were engaged in home work sewing false lining. An English book on fur notes, “The best are prepared and sorted in Weißenfels, Germany. This small place, Weißenfels is known all over the world for its furs and fodder. 500,000 false skins are trimmed annually; they provide employment for 6,000 workers, women and children ”.

In Russia, in the tobacco industry, there were famous malfunctions in the former Vyatka Governorate in the towns of Spasskoje and Slobodskoi , which also produced malfunctions. Slobodskoi still has an important fur processing factory, which is one of the largest in Russia. The fodder made from European furs came under the name "Russki" in the trade, those made from Uralic Feh as "Sawodski" (Sawod = Russian: factory), Ural-Sawodski-Feh were thus from the Uralic industrial area.

- Clerical miswear

One of the iconographic saints attributes of St. John of Nepomuk is the mozzetta , often recognizable from Fehfell, garnished with the tails (statue Johanneskapelle Eibiswald )

Canon Stephan Gardiner with an almutia made of a dewlap and a back over his arm (1st third of the 16th century)

Almutia from Fehwammen ( Bruges , undated)

- Historical miswear

Kunigunde of Austria (1465–1520) with trim on the back

Livonian women's costume with feehwomen (around 1600)

Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1757–1828) with back trimmings and cuffs (1757)

On the right figure skater Sonja Henie with a hooded back coat (1932)

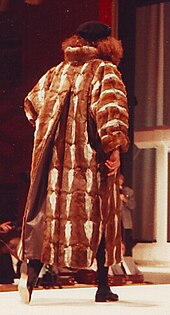

Award-winning all-over coat ( Dieter Zoern , Hamburg, approx. 1990)

Fell, trade

The head body length of the squirrel is 21 to 25 centimeters, the often bushy tail is 18 to 20 cm long. A hallmark are the tufts of hair on the ears (brush ears) and the two-lined, thickly haired tail. The dense hair is short, silky to coarser. In Eurasia, the distribution extends from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

- In Germany the squirrel is a particularly protected animal species according to Appendix 1 of the Federal Species Protection Ordinance (BArtSchV), also in Austria according to national and EU law. In Switzerland it is a protected species under the Federal Law on Hunting and the Protection of Wild Mammals and Birds (JSG). International trade is not regulated by CITES . The IUCN classifies the squirrel as Least Concern .

coloring

- 1. Winter

- Depending on the area, either dark gray to light gray or brownish red.

- a) Siberia, Northeast Europe, Scandinavia

- Predominantly gray in light to dark, sometimes almost blue-black tones.

- The origins / provenances Obsky (Siberia) are characterized by a clear gray, as long as the attack does not contain red-streaked varieties ("gorbolissky").

- b) Eastern Europe to Western Europe

- Lighter in gray to brownish red.

- In general terms, the colder the area, the purer the gray (without reddish stripes).

- The belly side is always white.

- White and speckled coloring are rare.

- In contrast to other fur species, squirrels' skins are not necessarily better the harder and colder the winter is. In such inhospitable weather, the animals stay in their nests or live on the supplies they put up in autumn. In both cases, the development of the fur suffers, either it is worn off or only poorly developed.

- 2nd summer

- The summer color is brown-red to red in all areas, sometimes brown-black to almost blackish (including in the mountainous areas), in Siberia it is partly still gray. The reddish color extends in stripes, from the head over the back, to the sides and the end of the fur getting wider. In the better varieties, including those from Siberia, the red stripes in summer are gray in winter. The dewlap has a brownish to reddish edge.

Classifications

Shah Ismail I of Persia with gray-reddish back trimmings (1487–1524)

The main amount of skins comes from Russia - Siberia.

- In Europe, the coat color becomes purer in gray from the south to the north and northeast. In individual areas, reddish and blackish colors occur side by side.

- Starting from the Ural Mountains , the skins become flatter and lighter towards the west.

- In Western and Central Europe the color is reddish to dark red.

- To the east they become smokers and darker.

- The East Siberian varieties are the darkest, South Siberian ones are also dark; but mostly smaller and less smoke (a coat with thick, not tightly fitting hair is called smoke).

- I. Europe

- 1. Western Europe - Southern Europe

-

2. Central Europe

- Central European skins are weaker in the hair; redder in color; medium-sized.

-

3. Alpine countries (Switzerland, Austria)

- Squirrels in the Alps have a medium to good coat quality; dirty gray; medium-sized.

-

4. Balkan countries

- Medium to good quality; musig (the soft hair has little standing); predominantly dark gray; medium-sized. The mountain goods are better.

-

5. Scandinavia

- Northern (Northern Sweden to Lapland):

- Good quality similar to Finnish varieties; dirty, medium and dark gray; lighter than Central European varieties.

- Central and southern:

- Weaker in hair; gray with reddish stripes; medium-sized.

- Northern (Northern Sweden to Lapland):

-

6. Finland

- The quality of the southern Finnish skins is weaker than that of the central Finnish; gray to dark gray with a reddish middle of the fur ( Grotzen ), but predominantly reddish, only about 10 percent are regarded as pure; medium-sized. They come from Lapland and have particularly strong hair and are also less red-streaked.

- 7. Russia

- Western (Sapadny):

- Western goods are valued a little higher than those from Scandinavia. The skins are delivered with the hair on the outside.

- Northern (Sewerny):

- Northern pelts are valued higher and larger than Lapland ware. They are usually delivered in bag form, with the leather on the outside and the tail on the inside.

- Central (Centralny):

- The value corresponds to the Finnish goods. The fur is delivered round, with the fur inside or outside.

- Northern Urals (Pechora):

- Is equivalent to the West Siberian goods. The skins are pulled off stocking-like with the leather facing outwards, open at the bottom, with the tail facing outwards.

- Central Ural (Savodsky):

- Quite light-colored skins that are often used for dyeing. The delivery takes place with the leather on the outside, open at the bottom.

- Western (Sapadny):

- II. Asia

- 1. Siberia

- The Russian trade standard differentiates according to origin:

-

a) Amursky (Far East):

- Large, silky, mostly dark gray with a reddish sheen. Dark, mostly mixed tails.

-

b) Sabaikalsky (forests of the high plateaus of Transbaikaliens )

- Almost black-blue, dewlap pure white; not too big; mostly with a black tail.

- The skins, which were previously traded as "Sakamina" at the fur trade center in Leipziger Brühl , came from Transbaikalia; today they are marketed as "Nertschinsky", for saddle and dewlap lining. They deliver the darkest backs and whitest dewlaps.

- Schmidt reported in 1844 about a variety that lives on the eastern Baikal on the Bargusin river . The animals are sable black in summer and blackish gray in winter. Their tails were often sold as sable tails.

-

c) Jakutsky (east of the Lena River )

- Nice in color, dark gray, blue gray and dark blue gray, tails mixed colors (no red); a little smaller. Raw fur delivery not stretched tight.

-

d) Lensky (from the Lena basin)

- Light blue with a reddish shimmer (from the deciduous forests), otherwise gray-blue and dark blue. Big, beautiful skins. Red, light brown, brown and dark brown tails.

- The dark gray fabric with a black tail is called “yassak”. Yassak is originally the name for the tax to be paid by the Tatar population to the tsar in kind , in the best sable and sable skins . See also the article Kronenzobel . Knyasek is the name for skins with a less dark tail.

-

e) Altaisky (northern forest areas of the Altai and valleys between Ob and Yenisei )

- The qualities and colors are very different, dark gray, sometimes reddish brown; silky. Dark, dark brown, brown and light brown tails.

-

f) Obsky (basin of the Obflow)

- Big, good quality; blue and light blue, the guard hair speckled evenly, lightly to blackish. Few reddish varieties; Tail brown to light brown.

-

g) Teleutka (Basin of the Ob, the Lena and from the Altai Mountains )

- Particularly large skins with impressively beautiful but somewhat coarse hair. Light gray to almost white gray. Long, mostly silver-gray or gray-yellow tails.

-

a) Amursky (Far East):

-

2. China-Mongolia ( real squirrels )

-

a) North - former Manchuria ( Harbin , Heilongjiang )

- It's the best Chinese variety. The skins are similar to the Amur feh, but mostly dark, often red-streaked; medium-sized, tail particularly long; thick in the hair; black; Hair longer than the Siberian Feh. South Manchurians are weaker in their hair.

-

b) Other China, Mongolia

- Weaker varieties, similar to the southern Manchurian, come from here.

-

a) North - former Manchuria ( Harbin , Heilongjiang )

- The Chinese traditions are almost only sold in prefabricated form.

-

3. Sakhalin

- Sakhalin- Coming are similar to Teleutka-Feh; big; musy hairstand.

- 4. Japan ( Japanese squirrel )

- Either there are no more pelts from Japan, or at least the incidence is insignificant, in 1988 it was assessed as “probably very low”.

Russian raw fur range

European Russia accounts for 25 percent of the annual Russian volume and Siberia for 75 percent. (As of 1988)

In particular, in terms of coloration, the skins differ greatly depending on where they came from and the time of the attack; Depending on the large number of items, a very differentiated sorting is possible. The following criteria apply to the raw range:

- According to the tail color:

Blacktail.......... schwarze Schweife Lightbrown.......... hellbraune Schweife Darktail........... dunkle Schweife Redtails............ rote Schweife Darkbrown.......... dunkelbraune Schweife Greytails........... graue Schweife Brown.............. braune Schweife

A distinction is also made between:

- Colours

- a) purely monotonous (gray) over the entire surface, the upper hair may be colored a little red-brown.

- b) Semi-pure skins with a red-brown stripe on the back, which extends from the base of the tail to the middle of the back.

- c) Striped skins with a strip of red-brown hair on the back that extends from the base of the tail to over the middle of the back.

- sorts

- I . Thick-haired fur with a thick undercoat and thick, even upper hair over the entire surface of the fur.

- II . Less densely haired with less densely haired undercoat and upper hair.

- III . Half-grown skins with a little reddish color from head to front paws.

- According to the time of the attack , a distinction is made between:

-

a) winter goods

- Pure white leather; Undercoat dense; Dewlap always white.

- Skins with a light green color (transition period) are designated:

- Sinerutschka = green color on the paws

- Sinegolowka : = green color on the head

- Vosjanka = green color on the dewlap

-

b) autumn goods

- Sinjuscha = leather greenish; Fell less smoke.

-

c) Early autumn goods

- Podpal (Podpol) = greenish leather

Red-lined feh are called "gorbi-lisski".

- According to the type of delivery :

-

Pologurska (English: cased)

- Hides open at the back (open pump ), leather and tail outside.

-

Liguschka (Taschenfeh (English: pockets))

- Hides with closed pumps, tails inside, leather outside.

- Closed, round skins with the hair facing outwards are called "hairy" = better in the hair, with the hair inside as "leathery" = better in the leather.

The Russian auctions bundle the offers according to their origin in lots of 2,000 to 3,000 pieces each (Jakutsky, Amursky, Sabaikalsky etc.)

and within these traditions according to units (Russian: golowki), as well as according to weight (Russian: wjes), as a rule between 53 and 70 kilograms.

In addition to the differentiation of types, Russian males are also differentiated according to the hunter's removal of the skins. There is the Poluguska or open Feh and Ljaguschka or Taschenfeh (closed at the back), usually referred to in English as Pockets in trade.

Red squirrel

In the past, the red European squirrel was considered unsuitable for fur processing. On the one hand, the flat, not very dense fur appeared unsightly after the fur was trimmed, on the other hand, the glass-hard, brittle guard hair could not be sufficiently pretreated for coloring. In the 1920s, however, German fur refiners succeeded in shrinking the leather using a special type of chroming , so that the hairline then appears fuller. The hair becomes more stable and takes on the character of the smoking and thick-haired false coat. A bleaching process, which has since been perfected, has now made it possible to produce bright fashion colors for trimmings as well as imitations of sable and mink.

The best qualities of the red squirrel came from colder regions and the mountainous areas. In the 1930s the main suppliers were Poland and Galicia, and good hides were also supplied by the Nordic countries, for example Sweden, Finland and Lapland. For the most part, they came to Leipzig in full stripping. At that time, even the most important foreign dye works had not succeeded in "bringing out this special article in anything even remotely similarly good". Because of the lower costs, the skins were usually pre-cut into strips before the coloring process, either back to back or dewlap to dewlap. The Central German and Southern European traditions, with the exception of goods from the mountain regions, were less good in hair quality, but they were suitable as inner lining for textile clothing.

American squirrel

Of the American squirrels, only the American red squirrels and the American gray squirrels living in North America (eastern states of the USA, Canada and Alaska) are eligible for the fur trade, the fur is usually referred to as the Canadian Feh. The American red squirrels make up the largest proportion of fur. Skins of the species native to Central and South America do not reach the quality of the North American and especially not that of the European-Siberian varieties.

There are also a number of species of squirrels in Mexico . In a receipt from Düsseldorf furrier Johann Wilhelm Welen (Wolon) from March 1693 to his regent Anna Maria Luisa von der Pfalz , he charged her 8 ½ Reichstaler for the skins and 1 ½ Reichstaler macher's fee for a fur made from 100 Mexican squirrel skins, 1 Reichstaler macher's reward for the overskirt.

American squirrel skins are less full in their hair; very light and smaller; greyish-yellowish with a greenish tinge, red in summer.

According to the Hudson's Bay Company and Annings Ltd., London, the following peculiarities apply to Canadian varieties, from here the largest proportion of deliveries come:

- Color : red, partly dirty gray

- Origin (provenances):

- a) Western

- b) Eastern

-

range

- a) Regular : pure in color (clear), slightly shot (slightly shot).

- b) Winter pelts : captured in winter, blue dewlap.

- c) Secondary : Weaker in the hair

- d) Damaged : damaged areas (with bullet holes).

The raw fur is delivered round, with the hair pulled inwards.

The skins are usually colored, light brown (chocolate, milk coffee), they used to be used as a substitute for colored ermine skins . It is processed into fur of any kind, preferably inner linings.

processing

Until the first half of the 20th century, various types of fur came from China as semi-finished products, assembled in the shape of a cross, into world trade, including as square crosses and split crosses made from the fur remnants.

From these crosses, a coat in the Chinese shape customary at the time could be made in the simplest way (closing the seams on the side). Until the first half of the 20th century, the crosses were also exported as semi-finished products all over the world. Then the Chinese furriers adapted to the western market and only supplied the usual rectangular bars in coat length.

“ The pictures on the right show an interesting Chinese work made from False Claws.

As is well known, the Chinese furriers are extremely thrifty workers who know how to make a profit from even the smallest fur waste. We can sometimes find their way of working and their taste difficult to understand. But if one studies such complicated work more closely, it seems clear that in addition to the commercial motivation, cultural influences that are to be valued more highly also played a role in its execution.

In the work on the left, it was not clear how a larger, uniform surface (in the present case a coat in the shape of a cross) could be produced from the flat parts of the false claws. The solution to the question has now been attempted as follows. The claws, (about 7,600 in number) have first been sorted into two by the smoke. Then these 2 claws have been cut across at 4 heights. The 2 upper, smoky pieces were placed next to each other; the other 6 pieces in the middle, divided lengthways and then, according to the haircut, attached to the top pieces on the right and left. In this way a strip of about 9 cm was created. Width and 1 cm height. Hundreds of such stripes were then placed on top of one another, the smokest upwards, Fig. 2 represents 3 half such bands which in the cross, Fig. 1 occupy the space filled with black (hair side and leather side).

The bands are then assembled in a cross shape as shown in FIG. The work contains about 55,000 small pieces that have created over 1,100 m of seam. The finished cross was then blinded in sable color.

This huge work makes the impression of pressed velvet. Since every single band diverges in the line, lighter and darker longitudinal stripes form for the eye, as can also be seen in the photograph (N ° 2). "

Siberian skins were partly exported raw, partly prepared, partly processed, today mainly pre-processed into semi-finished products, as bars or the larger variants, called fodder. The back and dewlap are usually separated, reddish varieties are usually colored. If fur linings were sewn together in a round shape and traded closed at the bottom, they were called sacks (Fehsäcke).

Assortments of loose backs were grouped into hundreds of bundles, each with 5 bundles in a hundreds cord. A ready-bundled and sorted product came from Weißenfels, with the reddish skins usually finished in sable color. The natural goods were sorted: AA = very light gray backs, A = light gray backs, B = medium gray backs and C = dark gray backs. The colors were again divided into point goods: Without point = completely pure colored back, one point = not completely pure color, two point = slightly streaked. The skins were sorted into rooms (40 pieces), with 5 rooms each being put together for a range of coats. The tradition was also given. In 1929, the Russian misfitting took over this range of products.

Fault boards are delivered today in the following sizes:

- Russian-Siberian origins = 80 × 115 centimeters (2 panels correspond to one food)

- Chinese origin = 60 × 115 centimeters (5 panels = 2 linings)

Feet back linings are offered in two or three parts, the backs are arranged in rows and strips next to and one above the other.

Fehwammen linings are either normal (like Fehrücken) or as "Vintom" (English: row, Russian: rjad) half-skinned, helically diagonally worked. A more or less wide part of the dark fur sides is always left on the white belly parts. Otherwise, the dewlaps are usually put together “half-skinned”, that is, separated into right and left halves of the abdomen, the bars and lining are always traded in pairs. Occasionally, fodder made from whole skins is also available on the market (Ganzfeh). In the past, there was a piece of tail on the back of the fodder sewn into sacks.

In 1965, the fur consumption for a fur board with up to 240 feet (so-called “body” ) was specified for a fur panel that was sufficient for one back coat . A board with a length of 112 centimeters and an average width of 150 centimeters and an additional sleeve section was used as the basis. This corresponds roughly to a fur material for a slightly exhibited coat of clothing size 46 from 2014. The maximum and minimum fur numbers can result from the different sizes of the sexes of the animals, the age groups and their origin. Depending on the type of fur, the three factors have different effects.

All waste, such as foreheads, mumps, throats and heads are sewn together to make panels. There is also neck lining, neck and head lining and "obljastschatij". The latter consist of whole summer skins or short podpals (skins with greenish leather). The brush ears were previously dyed black and served as a termination for the artificial ermine tails, especially for ermine sleeves, fur scarves and hats. For the processing of pieces of fur, see also the article fur scraps , for the production of artificial crook and ermine tails, sometimes even by special companies, see the article tail turning .

In particular, the lively Fehwammentafeln are now mostly processed into inner linings, the backs into all kinds of large-scale clothing, but above all into trimmings, trimmings and fur accessories.

The leather is particularly quick (stretchable when moist). Depending on the model and fashion, a simple Fehmantel takes about 80 furs, but mostly the back fur and the peritoneum are processed separately. A Leipzig guild chronicle from 1732 estimates 180 backs in eight lines for an inner lining.

- Modern Feh finishing and processing

Numbers and facts

- Around 1600? , Quote: ... and Siberia became the promised land, where in the first decades people went exclusively to hunt sable and to exploit the wealth of fur. - In the later years there were also those "deported" who had to serve their sentence by fishing for fur. The number of fur skins to be hunted and delivered to the state was z. On Kamchatka , for example, every year 5 sables, 50 squirrels, 2 foxes and 24 ermine skins per head of those “sent”.

- Around 1700 , quote: In addition, the Tartars of the Crimea, when they were still under Turkish sovereignty, took over the procurement of Russian fur to Romelia , Constantinople , the Greek islands , Trebizond , Sinope , Amasia , Heraclea and the other cities of Anatolia . So z. For example, the average annual import of fur in Sinope is 200 fox pelts of low average quality at 25-26 piasters, further 100 fox pelts of medium quality at 35-40 piasters, 20-25 marten pelts at 100-120 piasters, 300-400 furs from squirrels according to the different quality to 16-22 piasters and much more (1 piaster = 3 French livres).

- In 1775 the Russian government issued precise instructions to promote the exchange of goods with the Black Sea regions, with a simultaneous announcement of the goods prices applicable there and the likely profit margin that could be achieved on exports from Russia to there or to Constantinople. The following was given for Feh: White Siberian squirrel skins or Grauwerk the thousand at a price of 265 rubles to Taganrok ; minus all costs up to the sale of the goods in Constantinople at 340 rubles, resulted in a profit of 53.91½ rubles. Black Nerchinsky gray work yielded a utility of 52 rubles. The thousand cost 140 rubles in Taganrok, and 210 rubles in Constantinople.

- In order to fulfill its obligation to subsidize Austria, the Russian state sent 337,325 squirrel skins worth 6744 rubles to Vienna, along with other fur goods.

- In 1786 Nathan Chaim from Szklów ( Schklou ) brought 40 wagons with Fehwammen and smokers to the Michaelism Fair in Leipzig.

- 1813 to 1840; 1836-1837; 1838 to 1841

- Quote Jos. Klein, 1906, on the following three tables:

- One has to distinguish the Siberian gray work into West Siberian and East Siberian. The former, the cheaper, mostly goes to Europe, mainly via Radziwilow to Leipzig, where it forms a separate article in the fur trade, and the shipping from the port of St. Petersburg to England is not insignificant. Table VI gives this export for the years 1838-1841 and shows at the same time how insignificant the quantity of sables seduced by here was. The total export from Grauwerk to Europe was around 2 to 3,000,000 skins. v. Baer p. 162 The East Siberian, more expensive gray factory is bought by the Chinese. Table VII gives an overview of the squirrel skins which were sent via Kjachta to China in the years 1813-1840, whereby from Table VII the individual grades of the gray work which were dispatched to Kjachta in 1836 and 1837 can be compared. If we set the export to China at around 4,000,000 skins, the total export amounted to 8-10,000,000 gray skins. Domestic consumption was also extraordinarily high and significantly exceeded sales abroad and is to be calculated on at least 8-10,000,000 skins. Accordingly, the total yield of the hunt for gray work was a good 15,000,000 pelts. The gray works of West Siberia was worth an average of 75 RS for the 1000 pieces; after deducting the high transport costs, the 1000 pieces would be significantly more expensive: so we would have the round sum of 1,500,000 RS average annual income for gray works.

Zobelwert = rund 200 R. S. = 30 : 2 = 15 : 1 Grauwerk = 1.500.000 R. S. = 30 : 15 = 2 : 1 Das Eichhörnchen lieferte also gut die Hälfte zu dem Geldwert des sibirischen Pelzhandels, der Zobel nur den 15ten Teil.

| Export of gray works via Kjachta to China |

|

|---|---|

| year | Squirrel skins |

| 1813 | 5,267,236 |

| 1820 | 4,238,138 |

| 1830 | 3,182,577 |

| 1836 | 4,114,140 |

| 1837 | 2,931,347 |

| 1839 | 3,717,781 |

| 1840 | 4,344,140 |

| Export of gray works via Kjachta according to individual sorting |

||

|---|---|---|

| 1836 | 1837 | |

| Syrjänka | 816.100 | 381,592 |

| from the Irtysh | 247,547 | - |

| Obisches | 165.211 | - |

| Kuznetsk | - | 10,346 |

| Teleutja | 1,000 | 40 |

| Jennisseisches | 229,792 | 90,320 |

| Krasnoyarskaya | 14,784 | - |

| Nizhneudinskaya | 2,595 | 7.207 |

| Irkutskian | 6,552 | - |

| Lenskaya and Angarskaya | 1,448,859 | 1,483,672 |

| Yakutsk and Olekminsky | 577.734 | 542.738 |

| Okhotsk | 120 | - |

| Transbaikal | 593.089 | 476,727 |

|

Each sub-sorting takes its name principally from the river , where they will receive the collector. |

||

| Export to fur from the port of St. Petersburg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fur type | 1838 | 1839 | 1840 | 1841 |

| Squirrel skins | 380.060 | 2,010,266 | 674.506 | 1,080,347 |

| Squirrel tails | 1,796,012 | 1,856,849 | 2,330,950 | 1,955,345 |

| Hares, gray ones | 44,650 | 91,819 | 128,610 | 39,367 |

| Rabbits, white ones | 8,900 | - | 6,000 | 27,120 |

| Stoat | 45,320 | 56,680 | 18.193 | 65,130 |

| Cats | 411 | 1,164 | 1,246 | - |

| Badgers | 154 | 1.961 | 1,679 | 541 |

| sable | 710 | 53 | 30th | - |

- After 1918 , after the end of the First World War , 12 to 14 Marks were paid for the best and purest false skins. When Russia started delivering again, the price dropped to 2 to 2.50 marks per fur. The lighter Finnish and Norwegian material came to Germany around 1936 , but only in quantities of a few thousand pieces. Because of the increased demand, the trade turned its interest to the Tyrolean and Austrian squirrels, which had previously never been noticed. “ Suddenly they became an object of value, around 50 to 60 pfennigs were paid for raw goods that came on the market in quantities. It had to be dyed on mink and sable because they naturally could not be processed and made a good coat decoration, coats were also made of the best quality ”(until the beginning of the Second World War).

- In 1926/27 and (1925/26) Russia exported 8,582,760 (10,389,059) untanned and 11,088 (16,807) prepared squirrel skins.

- In 1929 , the best quality natural-colored Fehrückenfutter cost 1200 to 1500 marks, the best natural Fehwammentafel 180 to 200 marks.

- In 1931 you paid around 3,000 marks in Germany for a Fehmantel (Fehrücken) of average quality. In comparison, a coat made of fehkanin ( rabbit fur dyed in a false color ) cost an average of 600 marks.

- Before 1944 the maximum price for Ganzfeh natural or colored was 5.50 RM, for Fehrücken 5, - RM.

- In 1986 the Russian auction offer amounted to 1.1 million skins and 9000 food tablets.

- In 1987 there were 0.8 million skins and 4500 fodder.

- In 1988 , the annual incidence was several million false skins, three quarters of which came from Siberia and a quarter from the rest of Russia.

- North American squirrel pelts ranged from 1 to 3 million at the time, approximately 300,000 of which were from Canada.

literature

- The squirrel (Feh) and its fur . Paul Schöps et al. In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 4, 1958, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 154-163.

See also

Web links

Individual references, sources

- ↑ Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: The fineness of the hair - the fineness classes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. VI / New Series, 1955 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 39–40

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XVIII. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950. Keyword “Feh”.

- ↑ Grimm, German dictionary sv "fech": varius , bunt, ahd. Fêh , mhd. Vêch , "it has survived almost only for the colorful fur, buntwerk, das fech, swiss. Väch, fr. Vair: daz (aichorn ) is red in some lands and in other lands is ez praun or grâw and if ez is even liehtgrâw, sô is ez vêch, wan daz vêch tierl is the same natûr, ân daz ez has a different varb, and how ez gevar is, yes ez is alzeit reasons weiz. Megenberg 158, 9. [...] Henisch 1027 still leads fech, blaw eichhorn, sciurus caesius and gunterfech , of which more below kunterbunt is to say, see. sv "spring colorful". dwds.de by Pfeifer, Etymological Dictionary of German , 2nd edition (1993): "In the 17th century, Feh is attested as a name for ermine; the transfer to the Siberian squirrel probably took place in the 18th century. "

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan, Bochum: On the history of the smoking goods trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century . Inaugural dissertation University of Cologne 1940, p. 67

- ^ A b Marie Louise Steinbauer, Rudolf Kinzel: Marie Louise Pelze . Steinbock Verlag, Hanover 1973, pp. 57-58.

- ↑ a b c Paul Larisch : The furriers and their characters. Contributions to the history of furring , 1928. Self-published, Berlin, pp. 52–56, 148.

- ↑ Art. Mantel , in: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , Volume 19, here: p. 239.

- ↑ Catherine Panter-Brick: Hunter-Gatherers. An Interdisciplinary Perspective , Cambridge University Press 2001, p. 52.

- ↑ B. Brentjes: The oldest surviving boot made of leopard skin . In: Das Pelzgewerbe 1966 No. 4, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin a. a., pp. 172-173.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan, Bochum: On the history of the smoking goods trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century . Inaugural dissertation University of Cologne 1940, p. 20. Table of contents . Primary source: Friedrich Hottenroth: Handbuch der deutschen Tracht . Stuttgart undated, p. 161

- ↑ Bruno Schier : Ways and forms of the oldest fur trade . Archive for fur studies Volume 1, Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Frankfurt am Main, 1951, p. 40. Table of contents .

- ^ A b Francis Weiss : From Adam to Madam . From the original manuscript part 1 (of 2), in the manuscript pp. 68, 134 (English).

- ↑ Historical - Middle Ages - French kings' fur supplies . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVI / New Series 1956 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, p. 12. Primary source: Weite Welt , Berlin February 1948.

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Rheinische Friedrich-Humboldt-Universität Bonn, 1900. pp. 35–36.

- ^ A b c Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 1. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 19, ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Rheinische Friedrich-Humboldt-Universität Bonn, 1900. P. 28. Primary source v. Baer, p. 163.

- ^ A. Feldmann, Berlin: The German furrier house trade . In: IPA, International Fur Exhibition , International Hunting Exhibition, Leipzig, 1930. Official catalog. , P. 254

- ^ BP Bukow: The Leipziger Brühl then and now . In: Die Pelzkonfektion March 1925 No. 1, Berlin, p. 14.

- ↑ Georg Jacob : What trade articles did the Arabs of the Middle Ages obtain from the Nordic-Baltic countries? . Mayer & Müller, Berlin 1891, p. 42.

- ^ Geo. R. Cripps: About Furs. Liverpool, undated (1903), p. 75 (English).

- ^ A b c d Siegmund Schapiro (Leipzig tobacco shop): Russian tobacco products. In: "Rauchwarenkunde - Eleven lectures from the product knowledge of the fur trade", Verlag der Rauchwarenmarkt, Leipzig 1931, pp. 79, 80.

- ↑ IUCN Species Account (Retrieved October 5, 2008)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel's Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10. revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, pp. 134, 176-181.

- ^ A b Hermann Deutsch: The modern skinning. Manual for the furrier, dyer, bleacher, cutter and garment maker . A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig, 1930. pp. 53–56.

- ^ Christian Heinrich Schmidt: The furrier art . Verlag BF Voigt, Weimar 1844, p. 11.

- ↑ Note: "Units" are mainly specified when small quantities do not allow pure assortments. Index numbers then indicate how much lower the auction company estimates the content compared to a pure lot.

- ↑ Without author's indication: Refined Squirrels and Feh . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 74, Berlin, September 13, 1933.

- ↑ Jürgen Rainer Wolf (eds.): The cabinet accounts of the Electress Anna Maria Luisa von der Pfalz (1667–1743) , Volume 1. Klartext Verlag, Essen, 2015, p. 170. ISBN 978-3-8375-1510-7 .

- ^ Paul Schöps, in collaboration with Leopold Hermsdorf and Richard König : The range of tobacco products . Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin 1949, p. 21. Book cover .

- ↑ Paul Schöps u. a .: The material requirements for fur clothing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVI / New Series 1965 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin a. a., pp. 7-12. Note: The information for a body was only made to make the types of fur easier to compare. In fact, bodies were only made for small (up to about muskrat size ) and common types of fur, and also for pieces of fur . The following dimensions for a coat body were taken as a basis: body = height 112 cm, width below 160 cm, width above 140 cm, sleeves = 60 × 140 cm.

- ↑ Gisela Unrein: A master furrier from Brühl remembers - in conversation with August Dietsch. (VI) . In: Brühl No. 3, May / June 1929, p. 29

- ↑ Paul Cubaeus, "practical furriers in Frankfurt am Main": The whole of Skinning. Thorough textbook with everything you need to know about merchandise, finishing, dyeing and processing of fur skins. A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna, Pest, Leipzig 1891, p. 314

- ↑ Erich Rosenbaum: The masterpiece order of the Leipzig furriers . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume VII / New Series, 1957 No. 4, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig a. a., p. 162. Primary source: Hauptbuch Vor E. Ehrsames Handwerck der Kürschner where parts written in Drey describe what happened in 1524 in the registered guild. Described and collected by Johann George Herttel as a craftsman's scribe. Leipzig 1737.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan, Bochum: On the history of the smoking goods trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century . Inaugural dissertation University of Cologne 1940, p. 100. Primary source: Beniowski's travels through Siberia and Kamchatka via Japan and China to Europe . Berlin 1790, vol. III, p. 32. Cf. Bruno Kuske: The global economic beginnings of Siberia and your neighboring areas from the 16th to the 18th century. In Schmoller's yearbook , volume 46, volume II, Munich and Leipzig 1922 p. 88, article II.

- ↑ Reinhold Stephan, Bochum: On the history of the smoking goods trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century . Inaugural dissertation University of Cologne 1940, p. 113. Primary source: v. Peyssonel: The Constitution of Commerce on the Black Sea. Translated from the French, Leipzig 1788. pp. 101, 301, 457.

- ↑ v. Peyssonel: The Constitution of Commerce on the Black Sea. Translated from the French, Leipzig 1788, pp. 382, 384

- ↑ Stephan, pp. 115-116. Primary source: KE v. Baer: News from Siberia and the Kyrgyz Steppes . St. Petersburg 1845.

- ^ Josef Reinhold: Poland - Lithuania at the Leipzig trade fairs of the 18th century . Verlag Hermann-Böhlaus-Nachhaben, Weimar 1971, p. 119.

- ↑ Author's note (Jos. Klein): For most Russian Siberian fur, internal consumption is much greater than export. In Russia, because of the climate, furs are a necessity for everyone, in Siberia this necessity even increases to luxury down to the lowest class. This circumstance also makes a more precise assessment of the fur extremely difficult.

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . P. 52, p. 56-57.

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the Rheinische Friedrich-Humboldt-Universität Bonn, 1900. p. 192 Table VII. Primary source v. Baer, p. 162; Compiled from archival documents.

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . P. 71, P. 193 Table VIII. Primary source v. Baer, p. 239

- ↑ Jos. Klein: The Siberian fur trade and its importance for the conquest of Siberia . P. 192 table VI. Primary source v. Baer, p. 152.

- ↑ a b Kurt Nestler: Tobacco and fur trade . Max Jänecke Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1929, p. 107.

- ^ Otto Feistle: Rauchwarenmarkt and Rauchwarenhandel. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1931, p. 28. Table of contents .

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, p. 31.