Tibetan lamb

Tibetan lamb , also known as “ Tibet ” for short , Chinese Tan-Pih (Pih = fur), American also Tibetan, is the fur of the six-week to two-month-old lambs of the young Shanghai mouflon. Contrary to the trade name, it does not come from Tibet , but from northern China. Characteristic of the coat is its corkscrew-like curly structure. The fur length is about 80 to 110 centimeters; the silky hair is white to yellowish.

The fur is used for blankets and clothing purposes, especially for trimmings , smaller fur parts and accessories. Tibet is considered to be extraordinarily subject to fashion.

The durability coefficient for the type of fur was given based on general experience as 30 to 40 percent.

History, trade

Tibet is not, as the name suggests, the country of origin of the skins. The sheep breeds that live there are rarely used for fur purposes, they are mainly used for wool production and, in the past, as transport animals. In Tibet itself, nomads dress in their typical Lokbar , a long coat made of sheepskin or goatskin, which is worn with the hair side inward. Another, probably not proven source thinks that the name is derived from a district name Teibi (?). The first Tibet skins came in 1880 as a fur crosses over Irbit and Kiakhta to Nizhny Novgorod and Moscow . It was apparently assumed that the pelts came from Tibet. The Chinese traders also referred to the fur as the mandarin lamb.

In 1911 Emil Brass wrote that the Chinese had unanimously assured him that the living Tibetan lambs were sewn into cotton cloth as soon as they were born in order to prevent the curls from becoming wild and getting dirty from the yellow loess dust. Adult sheep of the breed are covered with a long, fine, little curled upper hair and a thick, taut, silky undercoat. The double-skinned “Chinese sheep blankets” were, however, worth significantly less than the young animal skins. The combed out undercoat came on the market as "Cashmere Goathair"; in Tientsin it was mostly mixed with the undercoat of common goats.

Tibetan fur crosses and the longer robes were semi-finished products from which the classic Chinese kimono jackets and coat shapes could be made in a simple manner . A smokers merchant from Leipzig reported that during his apprenticeship it was always a tough task to neatly stack these large piles of crosses (in this case kid's crosses ) with larger assortments . As it was said, people in China switched to the manufacture of skin sheets because the article Kidcrosses was probably noted in the American customs tariff, but Kidplates was not. This made it possible for the importers to bring these plates into the country at a cheaper tariff for a while.

The Tibetan lamb, with its appearance that is out of the ordinary with other furs, has long hair and curls, has always been exceptionally dependent on fashion. Apart from the varying demand, there were times Chowchings and Dahtungs with their fine wool and silky hair, and at other times Tung Chows. This change came about when the Tibetans were coaxed out of Tibet to imitate mouflon fur. The larger Tung Chows with their dense undercoat are better suited than the silky varieties. Originally, Tibetan skins were only consumed in China, where the upper middle class wore them as winter clothing. They were made into fur coats (" sleeved skirts " or long jackets made of 14 skins), into fur maquas (riding jackets) and into semi-finished products, the fur crosses and, less often, into fur robes (robes are longer fur crosses). They also disappeared from the international market, along with other Chinese sheepskins, during Chinese warfare, as they were apparently used as the fur lining of military clothing.

The hide was always tanned in international trade. There were large tanning factories in China. From there, exports went mainly to London and Hamburg, but also, following telegraphic orders, directly to Berlin, Leipzig and New York. The deliveries were made in boxes made of particularly hard wood, each with 200 or 300 pieces. Inside, orange-colored oiled paper protected the goods from water damage during sea transport. In 1930 sales to Europe amounted to around 600 thousand skins, 15 to 20 thousand crosses (made from six to eight skins each) and ten thousand robes (made from 14 skins each), with consumption in the country "of course much greater". After that, the demand fell sharply and the country was used to a greater extent for wool processing.

Much of the skins were dyed black, but fashion colors also began to appear increasingly in the 1920s. Dyeing suffered the curls in the Leipzig dressing with wood colors, but this could soon be remedied by coating the skins with a light vinegar solution after the fur finishing . The company Martin & Sohn, London, on the other hand, combed the skins and dyed them in beautiful pastel shades. These new colors helped the type of coat to boom as trimmed fur at that time. It is said that “the customers in London and Leipzig have lined up to buy large quantities”. The main customers were also Italy and Poland. The best color was supplied by London, and France also dyed in good quality. As early as the 1920s, like today again, the skins were sometimes colored multicolored, but at that time "this method was not established". With the skins drawn out by combing or roughening, a mouflon, white fox or blue fox-like appearance was achieved.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Tibetan skins were mainly used for sets (multi-part accessories), which at that time were mainly manufactured by wholesalers at cheap prices, especially for "fragrant-looking, brisk" girl sets for ice skating and sleigh rides. Combed goods were used as a substitute for arctic foxes . Tibet was always in high demand, especially for trimming purposes, when long-haired pelts were fashionable. In the first quarter of the 19th century it enjoyed some popularity as a stroller blanket, and Tibet was also used a lot for normal fur blankets and as rugs .

After the Second World War (1939 to 1945), Tibet continued to be traded to a relatively small extent; coats and jackets in particular were rarely made from it. With the renewed increase in fur accessories around the turn of the millennium, small parts from Tibet, such as scarves, boas and vests, increasingly came into fashion, naturally white (usually also bleached), black, multi-colored and in all fashion colors. Fur has also been used more often again recently for trimmings on textile and fur clothing, especially on small parts such as chasubles or short jackets.

Commercial grades

The fur of the 1 ½ to 2 month old lambs is very long-haired, thinly silky and finely curled. The finer the curl, the more valuable the fur. The color is white to yellowish with a moderate sheen.

Tibetan lambskins come mainly from the northern Chinese provinces of Shanxi , Shaanxi and Zhili (roughly equivalent to today's Hebei ).

Tibetan skins were sorted into three qualities, I, II. And III. Before 1958, the deliveries mostly contained:

- 60 percent I. quality, 30 percent II. Quality, 10 percent III. Quality.

- A listing from 1958 distinguishes the following origins:

a) Chowching ( Shao Shings , Shia Shing )

- Slightly smaller curl, not very finely curled, very thick, silky hair, similar to a corkscrew curl. Dense undercoat, they are considered the most noble.

b) Dahtung (North Shanxi )

- Slightly longer and wider than chowchings with partly well-developed and finely crimped, very silky wool. The under hair is sometimes a bit stringy and thin, the quality is very good.

c) Tung-Chow (Rishilli = Hebei, south of Beijing)

- The largest variety, particularly large skins, are traded as "elephants". The good, strong curl has little sheen. The under hair is thick, the quality is good. This is where most of the skins come from.

d) Shantafoo

- The flat, open, and very thin curl is still silky, but less shiny than the chowchings and dahtungs. Except for the thicker leather, they are similar to the tung chows.

e) Sikaos

- Coarse curls, thin-haired and woolly, thick leather. Significantly smaller than the previous varieties.

f) Kalgans

- Also a coarse curl, short-haired and woolly. About half the size of the tung chows.

- Differentiation of the varieties according to appearance:

- Tibetan lamb is available in the long-haired varieties (7 to 8 centimeters) and the short-haired (3 to 4 centimeters) with a very beautiful, corkscrew-like curl. The finer the frizz, the more valuable the coat is. In addition, a less expressive variety with an open, more fully grown corkscrew curl comes on the market.

- Very long-haired (7 to 8 centimeters, longhair) with a beautiful corkscrew curl.

- Open-haired (loosehair): Corkscrew curl partially grown (curl more open, not very expressive).

Thibetine, mentioned in a specialist book in 1930, is a Mongolian lambskin that looks similar to Tibet. It was pointed out that the designation Tibet ("Thibet") is not allowed for this.

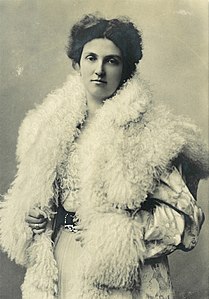

Lady Randolph Churchill with Tibetan Lined Cape (late 1880s)

Luise of Austria-Tuscany with a large Tibetan collar

(late 19th century)

processing

Sometimes the very thin epidermis of Tibetan skins tends to peel off in scales that are difficult for the fur trimmer to remove.

Further processing into fur products is uncomplicated thanks to the curly, long-haired hair structure.

Numbers and facts

- At the beginning of the 1880s , the first Coats came to Europe via Irbit and Nizhny Novgorod and were paid for with 300 marks.

- In 1875 at the London fur market, Tibetan pelts cost up to £ 1.25 each. "

- In 1887 the first direct shipments were brought to Germany by Emil Brass and paid for with around 130 marks, then larger quantities arrived and the price fell.

- In 1891 the first sewn hides came to Germany.

- In 1910 the price was 4 to 7 marks per piece, depending on the range and quality. The fur value fluctuated a lot, initially the same quality cost an average of 10 marks.

- In 1913, the Leipzig tobacco wholesaler Heinrich Lomer offered :

- Thibet skins - Agneaux de Thibet - Thibet Lambs

-

White

- Pure white, best curl pr. Piece M 9-10

- Great medium curl and medium-sized fine pr. Piece M 7-8

-

Black colored

- Big, finest curl pr. Piece M 9-10

- do. good curl pr. Piece M 7-8 .

- At the London fur market, Tibetan fur cost £ 5.30 to £ 5.50, and Tibetan robes £ 54 to £ 64.

- In 1920, Tibetan skins cost up to £ 3.50 per piece at the London fur market, and Tibetan robes up to £ 30.

- Before 1925 around 600,000 furs, around 20,000 (6- to 8-fur) crosses and 3,000 to 4,000 coats were exported annually (one coat contained 14 furs). The fur price was 12 to 18 marks. A “Chinese sheep blanket” made from two skins of adult animals rarely cost more than 3 to 4 marks. Around 50,000 to 100,000 such blankets were exported each year.

See also

annotation

- ↑ The specified comparative values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco shops with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are not unambiguous; in addition to the subjective observations of durability in practice, there are also influences from fur dressing and fur finishing as well as numerous other factors in each individual case . More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The division was made in steps of ten percent each. The most durable types of fur according to practical experience were set to 100 percent.

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 2nd, improved edition. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, p. 829-830 .

- ↑ a b Aladar Kölner (tobacco shop): Chinese, Manchurian and Japanese fur skins. In: Rauchwarenkunde - Eleven lectures from the goods science of the fur trade. Verlag Der Rauchwarenmarkt, Leipzig 1931, pp. 91-104.

- ↑ Paul Schöps, H. Brauckhoff, K. Häse, Richard König , W. Straube-Daiber: The durability coefficients of fur skins. In: The fur trade. Volume XV, New Series, 1964, No. 2, Hermelin Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig / Vienna, pp. 56–58.

- ^ A b c Marcus Petersen: Petersen's Fur Traders Lexicon . Petersen & Chandless, New York 1920, pp. 35, 85 (price list) .

- ↑ Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition. Publishing house of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, p. 686 .

- ↑ a b c d Paul Schöps: East Asian lambskins and sheepskins. In: The fur trade. No. 1, Volume IX / New Series, Hermelin-Verlag, Leipzig / Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1958, pp. 9-14.

- ^ A b Christian Franke, Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel ´s Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10th, revised and supplemented new edition. Rifra-Verlag, Murrhardt 1988, p. 300-302 .

- ^ A b c Richard König: An interesting lecture (lecture on the trade in Chinese, Mongolian, Manchurian and Japanese tobacco products). In: The fur industry. No. 47, 1952, p. 46.

- ↑ Unless stated by the author: Commercially available rawhide packaging. In: The tobacco market. June 18, 1937, p. 3.

- ↑ a b c Friedrich Lorenz: Rauchwareenkunde . 4th edition. People and Knowledge, Berlin 1958, p. 129-130 .

- ^ H. Werner: The furrier art. Publishing house Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, Leipzig 1914, pp. 107-109.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and Rough Goods, Volume XXI . Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1951, p. 201, keyword "Tibet" .

- ↑ Fritz Schmidt : The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer, Munich 1970, p. 368 .

- ^ Hermann Deutsch: The modern skinning. Manual for the furrier, dyer, bleacher, cutter and garment maker . A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna / Leipzig 1930, p. 133.

- ↑ Max Bachrach: Selling Furs Successfully. Prentice Hall, New York 1938, p. 173 (English).

- ^ Price list Heinrich Lomer, Leipzig, Winter 1913/1914 , p. 24.