Skunk fur

The coat of the American skunk or the Skunks belong to the 1940s to the essential materials of the fur fashion. Skunk fur has been on the market in Germany since around 1860.

The trade differentiates between Streifenskunks or Canada Skunks , the spotted skunk and the Zorrino or South American Skunks that the piglets Skunks belong. The skunks inhabit the American continent from the north to the extreme south in different species, only in Central America they do not occur (with the exception of the hooded skunk in parts of Central America).

The fur is usually referred to in the singular as Skunks (the Skunks, the Skunkse, often therefore also the "Skunksfell").

Appearance, origin and types of trade

With its plump, stocky body, the Skunk from the zoological family of the marten-like does not look like a typical marten. The head is small and pointed, the long-haired fur is rich in contrast. The basic color is deep black (technically also "blue") to dark brown. It becomes 40 to 50 centimeters tall, the long, broad and bushy tail reaches a length of 30 centimeters.

A special characteristic of the Streifenskunks is the drawing on the back, a white to yellowish “fork” that varies greatly in shape and size. The stripes are, essentially according to tradition, short or long, narrow or wide, mostly diverging towards the tail. There are skins that are completely black except for a white vertex, and on the other hand those that are almost completely white except for narrow black stripes. The more insignificant the fork mark, the more valuable the coat was, with otherwise the same quality. The beautiful hairy place between the forks is called a medallion by the furriers .

Even in the individual areas, for example the southern states, several species often live side by side. For this reason alone, the ratio of black and short-lined to white and long-lined skins is very different within the individual origins. The trade differentiates between black skunks, which usually have a small white spot on the forehead or the neck, short- striped, long- striped and white skunks. A further differentiation is made according to the striking difference between the eastern skunks with branched jagged stripes (Zackenskunk) and the western skunks with straight, non-jagged stripes.

Even with the raw fur , the leather side gives an indication of the quality of the skunk . A fully matured coat has a creamy, lively leather color. The leather of an animal caught too early is greyish in color. If the animal was caught late in the season, the leather is hard and stubborn.

Skunk skins are usually very durable, similar to raccoon skins . The shelf life coefficient was estimated on the basis of general experience at 50 to 60 percent, for those from Montevideo at 40 to 50 percent, for Lyraskunks at 20 to 30 percent. An American study classified the Skunk fur on the basis of microscopic hair examinations at 70 percent.

If the fur animals are divided into the hair fineness classes silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the skunk hair is classified as medium-fine.

North American Skunk

By and large, a tobacco specialist can determine the origin of the skins from the type of fork and the character of the tail. The Leipzig tobacco retailer Friedrich Hering even said that the white stripe is an unmistakable identifier for the retailer for the areas from which the skins come: If the fork is jagged, then you have a skunks from an eastern provenance in front of you, whereas the stripe is narrow and thin, this is how the fur comes from the west, such as Iowa and Wisconsin. Furthermore, if the white is yellow, the skunks are definitely from the east, pure white stripes also indicate western fur. But the percentage of black to short stripes compared to long stripes or whites gives an indication of the provenance. Skunks deliveries from eastern areas generally contain a maximum of 40% black and short-striped fur, Minnesota's 10%, Missouris about 50%; on the other hand, 60% and more of the Skunks of southern origin are found.

| Eastern type | Western type |

|---|---|

| Eastern | Minnesota Dakotas |

| Michigan | Northwestern |

| Northern New York and Northern Ohio | Iowa |

| Ohio Pennsylvania | Canadian (Western) |

| Indiana-Illinois | Kansas-Nebraska |

| Kentucky-Tennessee | Southern and Southwestern |

| Virginia Carolina | |

| Southeastern |

In the main time of Skunk fashion, the white forks were usually cut out when processing fur. In the case of the eastern qualities, this is made more difficult by the jagged pattern, which usually reduced the commercial value of the skins. Dyeing is not always recommended as the strips do not have the same silkiness as the rest of the hair. The forks were used separately for fur blankets , fur linings and collars when there was enough attack .

- The Hudsons Bay Skunk , central Canada, provides the largest skins. From the broad apex a narrow white stripe extends back to the shoulders, where it divides into two wide white forks that unite again towards the end of the fur. The blunt tail is very bushy and consists of quite stiff, bristly, black and white mixed hair. The leather of this type is usually quite dark reddish yellow, the second qualities or the summer goods have a dark green leather. The shape of the forks can also be clearly seen in the case of round skins with the hair pulled inwards; they stand out in yellow or orange from the rest of the leather.

- Kansas-Nebraska Skunks are much smaller than the skins from Canada, the hair is much coarser and a bit brownish. A common name in trade was “KN” for short.

- Minnesota Skunks , better Western Skunks according to Bachrach , are particularly large and darker than Hudsons Bay, the fork strips are only pencil thin, the hair is smoke to very smoke. This variety, most sought after in the American fur industry, was also in demand elsewhere, so it was said at the beginning of the 20th century that it is particularly popular with Berlin wholesalers because of its large size and easy processing . As a result, more pelts of the same provenance were on the market than were caught, because other origins were already being sorted into product ranges in America.

- The Northeastern Skunks are smaller and have darker, finer and silky hair, often they are glossy bluish black. Sometimes they only have a white spot or a narrow stripe up to the shoulder. Occasionally there are also completely white pelts that have only a narrow, dark back line and a dark dewlap. The finest and therefore most valuable come from the states of Wisconsin , Michigan , Ohio , New York and Pennsylvania .

- Kansas and Nebraska were very well known origins that were mostly traded together as one area. Even so, they weren't particularly popular because the hair is a bit coarse and stuffy. They are easy to recognize by their pointed heads.

- Iowa produced a lot of skunks. A distinction is made between North Iowa Skunks with a good size and thick and sufficiently silky hair of stocky quality and the smaller South Iowa Skunks, which is similar to North Missouri and was therefore often combined into one lot by collectors.

- Central-Skunks is from the Arkansas-Tennessee area. The fur is quite small and lacks an undercoat.

- Mississippi and Louisiana are even smaller than Centrals and of even lower quality.

- Oklahoma skunks are almost the size and appearance of a Minnesota skunk. It has a huge tail, which was usually cut off to hide its origin, as it is one of the inferior areas in terms of quality, the fur is thin and hollow.

- St. Louis Eastern , including the skunks from the areas east of St. Louis . These include the origins of Southern Illinois , Southern Indiana and Kentucky . The coat is medium-sized, but the quality is significantly lower than in the Eastern areas.

- Southern and Southwestern are very small, no larger than the average coat of the Northwestern area; strong brown-black and flat. They brought in the best prices in their size class after the Minnesotas. Oklahoma supplies many pelts that were also traded as Oklahomas .

- From the southern parts of Texas and parts of Louisianna comes the single-broad-striped variety, which is very coarse and sometimes bristly in the coat. The tail is also noticeably large, the hair is hard and thin. The white stripes converge to form a broad white spine, the white continues in the full width in the tail. After dyeing, however, the fur gets a very nice sheen. The skins were sold as Texas Broadstripes or Southern Broadstripes . Big skins with short forks come from Florida and Georgia , good in color but not silky.

- New Mexico pelts are large, very white, and coarse.

- California skunks are small in size with white forks.

- Skins of hooded skunk , Hooded Skunk or long tail Skunk be from the southern US to Central America, perhaps because of their often intense white back drawing, despite the silky hair as of little value designated for the fur processing, sometimes the so-called "white goods" will also be colored black or even bleached and dyed to lighter shades. The pattern can be very different, it ranges from the two color extremes - back and tail completely white or black back with two white side stripes - there are transitions in between. The belly is completely black. The hair on the back of the neck is usually spread in a frill. The head-trunk length is 30.5 to 40.5 centimeters, the tail length is 35.5 to 38 centimeters longer than the body skin. Otherwise it is generally said about the species widespread in Central America that they are of very poor quality (mostly stuffy). They are of no importance for the fur industry .

- Lyraskunk

- As Lyraskunks , formerly also Civetcat or Lyrakatze (not to be confused with the civet cat ), the trade describes a color variant of the Fleckenskunks . The body size is between 28 and 35 centimeters, the tail measures 17 to 21 centimeters. The hair is silky and dense, shorter and softer than that of the striped skunks. The lyre- shaped, white to yellowish-white stripes or spots stand out clearly from the glossy black basic color. Because of its light leather, Lyraskunks was already being used for inner linings at the end of the 19th century.

- In general, four types of spotted skunk are distinguished:

- The Western Fleckenskunk lives in western North and Central America , its range extends from British Columbia and Wyoming to central Mexico . The fur color is patterned in black and white; there are white spots on the face, white spots and stripes on the trunk, and an almost completely white belly. The black tail is closed off by a white tuft. With an average head-to-trunk length of 42 centimeters, the skins of males are larger than females, which are about 36 centimeters long. Both have a tail about 13 centimeters long.

- Eastern skunks from the area between the state of Connecticut and the Allegheny Mountains are smaller but very beautiful in color. The bifurcation turn on Pumpf from a right angle, so they are called pips Skunks. The skins are relatively narrow. The Eastern Skunk has four back stripes, the stripes are interrupted and give the coat a spotted appearance. There is a white spot on the front of the head. The head-torso length of the males is 46 to 69 centimeters, that of the females 35 to 54 cm, the tail length is about a third of the body length.

- The dwarf patchwork skunk inhabits a small area along the Pacific coast of Mexico . It reaches a head-trunk length of 12 to 35 centimeters, the tail is 7 to 12 centimeters long. The basic color is black; on the head there are white patterns, the body has two to six white stripes, which are arranged in a ring. The tail also tends to have white hair.

- The southern spotted skunk occurs from central Mexico to Costa Rica . It reaches a head-torso length of 12 to 34 centimeters, to which a 9 to 12 centimeter long bushy tail comes. The coat color is similar to that of the Western Fleckenskunk.

A basic division in the fur industry for the Fleckenskunk or the Civetcat is also the separation between white-tail types and black-tail types (instead of actually zoologically in three types, with the stink badgers four, or probably about 20 varieties). The black-tail type is commercially available as Northern or Iowa . It comes mainly from Iowa and Nebraska and includes some hides from neighboring states. The white tail types are divided into two varieties: 1. the Southern from Texas and the nearby states of Louisiana, Missouri and Arkansas; and 2. the Southeastern with more distinctive markings, but narrower fur than the rest, from the southeastern states of the USA.

South American Skunk

- The Patagonian Skunk is a protected species of the Washington Convention on Endangered Species in Appendix 2 of the Convention; For trade, export and import permits and proof of harmlessness for the population are required (listed in Appendix B since August 31, 1980 according to EC Regulation 750/2013). The fur is predominantly black, a white stripe extends along the back from the upper part of the head to the tail, and the tail is also mostly white. Above all in the southern part of their distribution area there is a type in which the stripe splits into two parts and leaves a brown-black back field free, which is reminiscent of the pattern of the stripe skunk.

- The Zorrino or Surilho is a representative of piglets Skunks with several species from Central and South America. Its fur is rarely traded, the already small fur often has an annoying vertebra in the neck that has to be cut away during processing. The annual volume was estimated at some 10,000 in 1970; in 1988 nothing was known about the quantity delivered. It must not be exchanged with the African zorilla , which, in addition to the similarity of name, also has a skunk-like appearance (also with a fork). The color of the Zorrinos is chestnut brown to black, the hair is very fine, but thinner and fluttering than that of the North American Skunk. The white fork markings vary greatly. Sometimes the back is white from the head to the tip of the tail.

In contrast to the North American Skunk, retailers attach little importance to the quality of the fork; it is not taken into account when sorting the raw assortment.

The best furs in smoky and silky quality come from the southern areas of Punta Arenas and Río Gallegos . The origins from Montevideo and Buenos Aires are coarser, less smoky and flatter . While quality and color are less noble on the seashore, better goods are found in the hinterland.

The provinces of Cordoba , San Juan , San Luis , Mendoza , Santiago del Estero and Salta supply small to medium-sized varieties.

The best varieties come from the valleys between the small and large Sierra of Córdoba. The fur is the silkyest, and much silky than the finest North American skunks, but the hair is less awny.

Furs from the Calmuchita Valley are particularly valued . At least around 1940, other qualities were also traded under the name.

Coarser and slightly larger varieties come from the lowlands of the Argentine provinces.

Entre Ríos Province delivers a special type.

The Corrientes and Santa Fe are similar in quality.

- The largest amounts come from Argentina . Three areas are the main suppliers of South American skunk skins. They are broken down again into different sub-zones:

- Eastern:

- Entre Ríos from the interior.

- Province or Provincias from the southeast coast.

- Montevideo on the east side of the Río de la Plata along the coast ( Uruguay ).

- Central:

-

Cordoba joins Entre Ríos to the west.

- Calamuchitas are large with dark spots.

- Mendoza , between Entre Ríos and the Andes. Mendozas are good colored, silky and short-forked.

-

Cordoba joins Entre Ríos to the west.

- Southern:

- Chubut , in southern Argentina, are small with a short fork, silky with a beautiful light or golden yellow color.

- Santa Cruz , also in the south, are similar to Chubut, also small, silky with a lighter back between the narrow forks, so-called Golden Centers .

- Magellan : Magellans are big, darker and silky.

- Eastern:

- The largest amounts come from Argentina . Three areas are the main suppliers of South American skunk skins. They are broken down again into different sub-zones:

- Peru, Chile , the skins from there are of no importance for fur purposes.

Smelly badger

The stink badger, which has recently been assigned to the skunk species zoologically, is mentioned in the fur literature as an animal with a usable fur, but in 1925 the fur was not yet used, and nothing seems to be known about its later use.

The Sunda stink badger lives in Sumatra , Borneo and Java ; the Palawan stink badger is on the Philippines -Insel Palawan is home and small islands.

The fur is dark brown to black in color. The Sunda stink badger has a white stripe on the back from the top of the head to the base of the tail, while the Palawan stink badger has only a single yellowish spot on the top. The legs are short and the tail is just a stub. They reach a head-trunk length of 32 to 51 centimeters, a tail length of 2 to 8 centimeters.

Zorilla, bandiltis

The already mentioned Zorilla , Bandiltis or Kapskunk , sometimes also Kapiltis, belongs to the bandiltiss according to the zoological system and thus belongs to a different subfamily than the Skunks or skunks. Outwardly, however, with its ribbon-like striped drawing from the snout to the base of the tail, it is quite strikingly similar to the American striped skunk. The few skins that he sold were mostly made into blankets or inner linings.

Trade, history

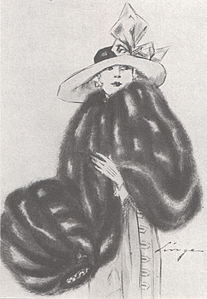

Stole Harald.

Elegant, straight skunks scarf on waffled, black silk, 320 centimeters long.

Skunks, 6 rows, quality B… M. 590, -

Skunks, 6 rows, quality A… M. 785, -

Skunks, 5 rows, quality B… M. 375, -

Skunks, 5 rows, quality A… M. 525 , -

Skunks, 4 rows, quality B… M. 300, -.

Skunks, 4 rows, quality A… M. 425, -

Muff Verena

Ultra-modern, extra large Skunks muff, hollow, made of silk.

Skunks quality A, 9 stripes… M. 340, -

Skunks quality B, 9 stripes… M. 270, -

Skunks quality A, 8 stripes… M. 320, -

Skunks quality B, 8 stripes… M. 240-

(CA Herpich Sons, Berlin 1910)

The use of the skins only became possible when the typical smell could be eliminated. The demand in North America itself was initially insignificant, the first time the "disreputable" fur was apparently not only offered there, often under different, veiling names, until the Skunkse was finally particularly valued and for a long time in the forefront of the most sought-after Fur established, the German furriers called the Skunkse around 1844 also muffettes. The first person to cut out the forks during processing was Bernhard Schild , who opened his business in Leipzig in 1898. However, no one knew what to do with them, they were thrown away. The world consumption of skunk skins has increased since around 1870.

In 1914, H. Werner wrote: "In 1859 you heard for the first time in Leipzig about Skunk, the rough, extremely decorative fur that has enjoyed great popularity especially in recent years ". Because of the light leather of some types, they were also often used for men's fur . Previously, they found little use at most locally. The global hub for furs, the Leipziger Brühl , distributed the imported Skunkse further to other countries, including Eastern and Southeastern Europe, and later also larger quantities to France, until the fur was finally also appreciated in the USA. South American skunks only gained significant importance in North America after the First World War. While it competed in use with the other types of skunks in Europe and Asia, in America it was mainly used for trimming fabric clothing and inexpensive fur coats. Over-dyeing with a light shade of blue increased the acceptance of the Skunk fur. The European market, however, remained the main sales area, if you were unable to take up the quantity of skins here, the price collapsed, for example at the time of the First World War .

In his history of the former Leipzig fur center, the Brühl , Walter Fellmann considers the Greek fur sewer Christos Pappagelias (* 1886; ‡ 1978) worth mentioning. Pappagelios came from the Greek fur scraps processing center Kastoria . He learned from 1904 in Leipzig, where he founded one of the fur clothing companies and specialized in skunks collars.

Until after the First World War, skunkse was a preferred material for trimmings, collars and sleeves, mainly for large coachman collars . In terms of total trade value, the Skunk was in second place in the USA after Muskrat. According to the IPA statistics of 1930, the delivery to the world markets was around 5 million skins. With the departure of fashion from long-haired fur , the deliveries also declined; after the Second World War, this fur material went steeply downhill .

The different species were not in the same demand everywhere. The finer varieties, such as New York State and other eastern origins, mostly went to Leipzig and Paris in 1930. Paris particularly preferred second grades, as well as black and striped goods. The trade from the east and south-east took over the larger, coarser goods, but also finer varieties that went to Budapest, for example. Southern Germany bought Minnesota and Dakota, other German areas bought western and northwestern varieties, among others.

After the increased demand for skunk pelts began, fur farms also started to breed skunk; around 1910 there were around 100 farms in the USA, and around 1925, according to an estimate by tobacco dealer Emil Brass , they supplied around a quarter of all fur on the market; but this was later questioned as probably too exaggerated. At that time the number of Skunk breeders was already decreasing, it had turned out that the breeding of silver foxes was much more lucrative, and the quality was worse than that of the wild caught.

While in the past the fur with the slightest crotch almost always achieved the highest price, today it is often the most interesting drawing when designers opt for striped skunk. The price of striped pelts almost approached that of almost monochrome skins once before, when black and white dominated fashion in the 1920s.

1984 a fur expert is quoted: Skunk is therefore no longer an issue at Brühl (meaning the fur center around Frankfurter Niddastrasse , derived from Leipzig Brühl), the article has run out of steam. The coat is classified as too poppy and too heavy. If you take the fork out, “it looks like a bearskin.” Despite the good durability of most varieties and although long-hair fashion has been reinvigorated, especially as a trim, skunk skins continue to play no role in fur fashion (2011). Designers only occasionally deal with the somewhat conspicuous material.

Wholesalers made a distinction between the American and the London range of raw materials. In the American range, all seizures were put together (summer, autumn and winter coats) and then sorted into black, short-forked, long-streaked and white. The London range also used this color classification and numbering, but applied them within the seasons and was therefore more precise, for example summer fur I-IV, autumn fur I-IV etc.

The raw hides are delivered closed, leather to the outside, or cut open.

A furrier assortment made from prepared Skunk skins usually contained 40 skins (= 1 room).

The tails generally have no commercial value, but they have occasionally been made into blankets and similar fur. Hard-haired varieties are suitable for the brush industry. Some of the bristle part of the tail (around two thirds) was removed from the raw fur by the collector, the first link in the retail chain, in order to send it to the brush makers. The tails of the Spotted Skunks were much more in demand than those of the Striped Skunk, whose tail hairs are straight and do not tend to change to the corkscrew shape like those of the other species. The hair was cleaned and made into cheap long-haired brushes .

Like all natural hair, black skunks hair also fades over the decades, it becomes lighter and more brown. Thanks to the special longevity of the fur, small Skunk accessories from the first half of the 19th century are still offered on the Internet, the fur color of which has changed to a reddish or rusty brown over the years (2012). Unfortunately, together with the color, the silkiness is also lost and the flair of this type of fur is no longer recognizable.

Processing, use

As soon as the peeled off Skunk fur arrives at the buyer, the fur is pretreated. With most Skunk varieties, the rawhide is particularly damp; if the leather fat was not removed, it would immediately rot as the temperature rises. The coat is (similar to that on a freed from the bark of tree trunk Gerber tree ) with a blunt, two-handed circular blade scraped off ( "scraped") and then dried. The fat that fell off was used in soap production, at least at the time. For the retailer, dark spots on the side of the hair are a sign that the fur may have been damaged before scraping, there are then bald spots after trimming .

An old textbook notes: “ This fur is just as uncomfortable for the furrier, with regard to its processing, due to its uneven hair, as the animal during its lifetime is due to its stench. No fur has hair so uneven in length and smoke as the Skunk; on the head almost as short as ermine, in the middle of the back it is as long as the fox, it falls off again towards the hind claws. From this something should now be fabricated, and the difficulty is increased by the fact that the head and pump (the rear part of the skin) are narrower than the elastic middle of the skin. The best skunks are completely black, then they become smaller and more difficult to work with because of the smaller or larger fork-shaped white and yellow markings that have to be cut out, even if the cunning tobacco shop, as is the case with smaller forks, already scissors the white had had them cut out and in this way put bald spots in the place of the white forks, which are covered by the hair and are less noticeable. “Ernst Kreft also remembers:“ Skunk, called the 'furrier's bread' at the beginning of the 20th century (my boss at the time informed me in 1907 of the record number of 90,000 processed Skunks in the past year), made my old colleagues a lot Difficulties in processing. Today it is child's play for us. "

Skunk fur can be used with all types of fur clothing as well as home accessories. From the beginning of its modern use, the material was mainly processed into trimmings and smaller items such as scarves, hats, necklaces (scarves in the shape of animals) and jackets, and in the 1960s and 1970s it was also used more frequently for capes, jackets and coats. In particular, the cheaper white skunks, which used to be delivered in larger quantities, are suitable as trimming material, appropriately colored. An American textbook mentions the 1967/68 season, in which the skunk husks were worked skin-on-skin, half-skin across or lengthways without cutting out the forks. Before the Second World War, when the forks were gouged out, they were made into tablets. These were usually dyed to make blankets, linings and collars. The remaining fur residues are also prefabricated into panels as semi-finished products if there is sufficient quantity .

For scarves, collars and the like, the forks were often left in the fur in the past. If the skins are delivered in a round shape, the skin is cut open at the beginning of processing and the thinly haired part of the belly side is removed in one piece. For processing without a fork, this is then cut out with the skinning knife while blowing the hair with a view of the color border at the hair outlet . A job that the textbook says requires practice and skill, but none of the valuable dark hair should be lost . In order to adapt the hair lengths to the medallion-shaped middle piece (grunt piece) again, the middle piece must be stretched up on narrow forks. If the cut forks are wider, the resulting hair length difference is also greater. In this case the medallion is moved up 2 to 2 ½ centimeters before it is sewn back together with the remaining fur.

The processing of Lyraskunk fur with its heavily ramified crotch is described in a specialist book in 1903. The skins were sold in undefined small quantities via large auctions in London. The fur processing took place partly in London, partly in Leipzig. The skins were usually divided into two types, those with white and those with yellow markings. Most of all, the dark ones with beautiful, regular white markings were appreciated. The two types were each sorted again into qualities A, B and C, the completeness of the drawing being decisive with the color of the basic tone. Most of the Lyraskunkskins were used for the inner lining of the fabric coats, with Russia being the main customer. Decisive for the use for food was probably the low weight, the good warmth, the good durability and the soft leather. At that time, however, the fur had already started to be used for trimmings, jackets and even coats. The material, which at first glance appeared “screaming”, appeared quite harmonious in the regular repetition of the lyric pattern. However, the models should be cut as simply as possible, as many folds easily gave the fur a lining-like appearance. Such larger parts gained “reputation” when a different, longer-haired (“smoker”) fur, for example bear or North American skunks, was added as a trimming. As a result, the lyric humor appeared flatter and the screaming of the drawing was softened. In order to achieve a mirror image of the entire item of clothing as possible, it was advisable to “move”. Here, one half of the fur is processed into the left, the other half into the right fur part. Often the drawing also had to be completed, otherwise no changes should be made within a skin, such as letting in or out . In order to make the transverse seams between the head and the skin less visible when they were placed on top of each other, the pluck was chipped off up to the first two spots, including the head, the flattest part of it, four to nine centimeters. The skins were then sewn together in such a way that the two patches of the torso came to rest on the two broad strips of the head, whereby a good transition was achieved without major loss of fur.

Some time after the invention of the fur sewing machine around 1870, it became possible at economic cost to change the shape of the skins as desired by so-called skipping . Here, the skins are made into any desired length at the expense of the width, especially through narrow V- or A-shaped cuts, up to a floor-length evening coat, with skunks with classic, single-colored processing after removing the forks. The opposite effect, a shortening while at the same time widening the fur, is achieved by letting it in. Skunkse were seldom left out down to the length of the shell, but these working techniques are also often used for shaping smaller parts.

The skins that are considered too light for natural use are blinded, that is, a darker color is applied from the hair with a brush or dyed, for light fashion colors after a previous decolorization ( bleaching ). Naturally colored skins are leather-blended by the furrier with a mostly dark blue aniline color during processing in order to prevent the light leather from showing through in the finished garment.

In 1965 the fur consumption for a skin table with 60 to 70 pelts sufficient for a Skunk coat was specified (so-called coat “body” ). A board with a length of 112 centimeters and an average width of 150 centimeters and an additional sleeve section was used as the basis. This corresponds roughly to a fur material for a slightly exhibited coat of clothing size 46 from 2014. The maximum and minimum fur numbers can result from the different sizes of the sexes of the animals, the age groups and their origin. Depending on the type of fur, the three factors have different effects.

Until before the Second World War, a number of Leipzig furriers had specialized in the manufacture of strips. The forks cut out of the skunks' skins were collected there and put together into larger, wide strips by specialists, including Greek furriers who had had this skill for decades. Most of them were made of fur ties , but also blankets, linings and collars.

The main places for recycling the fur leftovers are still Kastoria and the smaller Siatista in northwestern Greece. If there are enough Skunks pieces and Skunks forks, they go from Europe and America to there to be assembled into so-called bodies for later processing.

- Skunks processing at the end of the 19th century

Skunk colored finishings

In the great days of Skunk fashion, various other types of fur were dyed according to the color of the Skunk fur. The Skunkskanin was sold in large quantities and was widely known . Skunkskatze referred to a black-colored long-haired cat. Furthermore were stained skunk colored American Opossumfelle , Wallabyfelle , rabbit skins , flying squirrel skins Whitecoatfelle , fox skins , Wolf skins , Pahmifelle , raccoon skins , goat and Zickelfelle . They were also given the addition Skunk or Skunks, i.e. Skunk (s) hase, Skunk (s) opossum, etc.

Around 1926 a Skunk coat of average quality cost around 250 marks, for example, the cheaper imitation from Skunksopossum around half, 125 marks.

Again and again, the interesting fork of Lyraskunk is sprayed onto other types of fur with the help of stencils, for example onto white rabbit fur and kids.

Conversely, the skunk fur was also used to imitate other, even more valuable types of fur and, depending on the fashion, was dyed sable, marten or blue fox, for example.

Numbers and facts

Detailed trade figures for North American tobacco products can be found at

- Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911

- Emil Brass: From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition, publisher of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925

- Emil Brass: From the Realm of Furs (1911)

- Milan Novak u. a., Ministry of Natural Resources: Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America . Ontario 1987 (English). ISBN 0-7778-6086-4

- Milan Novak u. a., Ministry of Natural Resources: Furbearer Harvests in North America, 1600-1984 , appendix to the above Wild furbearer management and conservation in North America . Ontario 1987 (English). ISBN 0-7729-3564-5

| Comparison of the sizes of skunk skins | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varieties ("Sections") |

Sizes * | Percentage of Stripes in Average Lots

** |

|||||

| XL | L. | M. | S. | Black and shorts |

Longs | Broads | |

| Eastern | 33 | 30th | 27 | 24 | 50 | ← 50 → | |

| Central | 34 | 31 | 27 | 24 | 40 | 35 | 25th |

| Minnesota | 40 | 33 | 29 | 26th | 5 | 85 | 10 |

| Iowa | 35 | 31 | 29 | 26th | 15th | 65 | 20th |

| Kansas-Nebraska | 34 | 29 | 27 | 24 | 20th | 60 | 20th |

| Southern | 29 | 25th | 22nd | 18th | Mostly broads | ||

| Southwestern | 25th | 23 | 21st | 17th | Mostly longs and broads | ||

| * These sizes are based on the average long stripes (long stripes) of the different varieties or origins ("sections"): The broads (wide skins) are about the same width, the blacks (black skins) and the small stripes (narrow-lined) are around 10 percent narrower . |

|||||||

| ** These percentages may differ slightly, depending on the collector and local customs. | |||||||

- Skunk sets

- In 1855 it was imported into London

- from Hudson's Bay Company countries: 5,945 skunks worth 6,743;

- from Alaska, Oregon, Canada etc .: 200 skins worth 40 ₤.

- In 1875 it was imported into London

- from the lands of the Hudson's Bay Company: 2,789 skunks worth 1,860;

- from Alaska, Canada, Oregon and the northwestern United States, bought from retailers and sold in London: 275,943 skins valued at ₤ 81,540.

- 1891 in a furrier book, the remark that seems strange to a professional today: Another disadvantage is the frequent occurrence of nits (lice eggs), so that on the whole, despite its current popularity, the skunk is not ascribed the predicate of a noble fur can. --- Skunk skins tend to peel off the epidermis , which might give the appearance of "nits". Nits would not survive the tanning process, and the remains of them would also be rinsed out afterwards.

- 1907-1909 , in these three years the total annual average production of Skunkskins from North America was 1½ million pieces, from South America 5000 pieces.

- 1911 tobacco merchant Emil Brass gives the value of a Hudsons Bay Skunk fur at 6 to 8 marks; 1925 with 12 to 20 marks.

- At the time, he wrote of the South American skunk, the Zorrino (misleading for us, also called Zorillo (little fox) by the Spaniards, see above) that only relatively very few come onto the market, only a few thousand pieces annually from Argentina . Considerably larger quantities could come, but they usually achieve such a low price, from 50 to 60 pfennigs each, that catching and collecting is not worthwhile .

- In 1925 , the tobacco wholesaler Jonni Wende offered: Skunks: natural, great black 20 to 30 Reichsmarks; natural, short forked 15 to 27 Reichsmarks; natural, striped 9 to 22 Reichsmarks; black colored 10 to 12.50 Reichsmarks.

- 1928 in a specialist furrier book: The London January auctions brought in 500,000 at CM Lampson & Co .; Fred Huth & Co. 200,000; Hudson-Bay Company 796,000 pieces. The New York auction in April 1928 brought up 163,000 Skunks. The range usually falls into five parts. The American auction sorted up to twelve species and also classified the skins according to origin, such as goods from New England, North Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan; Southeast Ware, Northwest Ware, Kansas, and Nebraska. Nordwestware achieves the highest prices.

- Skunkse tasted in 1929

- best "set", naturally dark 20, - to 30, - RM per piece

- Trimmings, stripes, natural 10, - to 22, - RM per piece

- colored secunda 7.50 to 10 RM per piece

- In 1930 , according to statistics from the IPA - Internationale Pelzfach-Ausstellung Leipzig, the annual delivery of Skunk skins to the world markets was around 5 million pieces. The Canadian Skunkse incidence is auctioned at the Hudson's Bay Company auctions. In recent years, the offer has never been more than 30,000 for the whole year.

- As of 1935 , skins in the American range were only sorted into four color classes, regardless of the skin quality: I. black, II. Short-forked, III. long-streaked, IV. white. In the London range, the skins were sorted according to the quality into winter, autumn and summer skins and in five colors: I. black, II. Short-forked, II. Narrow-striped, IV. Broad-striped, V. white.

- Before 1944 [ June 2, 1939 ] the wholesale price (maximum price) was for

- North American: best RM 30; medium RM 20, -; weak RM 10, -; colored RM 15, -

- South American: best RM 9; weak RM 4.50

- On February 3 and May 4, 1949 , 69,789 Skunkskins were withdrawn from the two London auctions of the Hudson's Bay Company and 139,768 from the second auction.

- In the 1961/62 season , according to the American " Fish and Wildlife Service ", around 61,700 Skunks were caught in the USA, in the next season 1962/63 it was around 47,000 and in 1966/67 only just under 34,000, ie compared to the time before after the Second World War a quite substantial decrease .

-

In 1966 (fiscal years), also in the USA, it was estimated at

500,000[appears incorrect, 50,000?]; In 1970 it was 21,874 and in 1971 (BDC estimate) 15,617.

- The change in the raw fur supply compared to the previous year was 1966 = - 8%; 1967 = -5%; 1968 = - 42%; 1969 = + 32%

- After the Second World War and the trend away from long-haired skins, deliveries also declined. In 1966/67 there were just under 34,000; 1970 about 22,000.

- In the 1971-72 season were only 179 pelts covered by striped skunk with an average price of 28 cents each in Canada.

- Before 1988 , between 15,000 and 20,000 fleckenskunks (lyric kunks) were produced annually .

- At the auction on June 5, 2012 , the Canadian fur auction house NAFA - North American Fur Auctions offered 10,033 skunk skins and sold 60 percent. The average price per piece was $ 3.69, the best heads fetched $ 23.

See also

Web links

- Arthur Holmes Howell: Revision of the skunks of the genus Chincha . US Department of Agriculture, Washington, 1901 (English). Retrieved September 29, 2015.

annotation

- ↑ The specified comparative values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco shops with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are ambiguous; in addition to the subjective observations of shelf life in practice, there are also influences from tanning and finishing as well as numerous other factors in each individual case. More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The division was made in steps of 10 percent each. The most durable types of fur according to practical experience were set to 100 percent.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j editorial team, with the collaboration of Richard Gloeck , Leopold Hermsdorf, Friedrich Hering, Richard König (all Leipzig tobacco shops), Dr. Ingo Krumbiegel, Alfons Haase (Buenos Aires): Skunk and its provenances . In "The tobacco market" XXXI. Vol. 1/2, Leipzig January 2, 1943, pp. 3–7

- ↑ Dr. Max Meßner, edited by E. Unger: Materials science for leather and fur workers. Alfred Hahns Verlag, Leipzig, 1910, pp. 23, 25, 29

- ↑ Duden , 25th edition, Dudenverlag, Mannheim a. a. 2009, keyword “ 2 Skunk” ISBN 978-3-411-04015-5

- ↑ a b c Friedrich Lorenz: Rauchwarenkunde , 4th edition. Volk und Wissen publishing house, Berlin 1958, pp. 105-108.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XXI. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1951. Keyword "Skunks"

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Friedrich Hering (Leipzig tobacco shop): Muskrat, Skunks, American Opossum. In: "Rauchwarenkunde - Eleven lectures from the product knowledge of the fur trade", Verlag der Rauchwarenmarkt, Leipzig 1931, pp. 36–40.

- ↑ a b c Arthur Samet: Pictorial Encyclopedia of Furs . Arthur Samet (Book Division), New York 1950, pp. 183-189.

- ↑ Paul Schöps; H. Brauckhoff, Stuttgart; K. Häse, Leipzig, Richard König , Frankfurt / Main; W. Straube-Daiber, Stuttgart: The durability coefficients of fur skins in Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume XV, New Series, 1964, No. 2, Hermelin Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig, Vienna, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Editor: The durability of fur hair . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt Nr. 26, Leipzig, June 28, 1940, p. 12. Primary source: American Fur Breeder , USA (Note: All comparisons put the sea otter fur at 100 percent). → Comparison of durability .

- ↑ Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: The fineness of the hair - the fineness classes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. VI / New Series, 1955 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 39–40

- ↑ a b c d e f Paul Schöps in connection with Paul Häse, zoological processing Ingrid Weigel: Der Streifenskunk . In "Das Pelzgewerbe" vol. XVII / new series 1966 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin a. a., pp. 72-84.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Max Bachrach: Fur. A Practical Treatise. Prentice-Hall, Inc., New York 1936. pp. 411-429 (English)

- ↑ a b c d e Emil Brass: From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition, publisher of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, pp. 633–642.

- ↑ a b c d e f Emil Brass: From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the “Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung”, Berlin 1911, pp. 531–539, import statistics, pp. 321–375.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel ´s Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10. revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Dathe , Dr. Paul Schöps, with the collaboration of 11 specialists: Fur Animal Atlas . VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1986, p. 184/185.

- ↑ a b c Paul Cubaeus, "practical furriers in Frankfurt am Main": The whole of Skinning. Thorough textbook with everything you need to know about merchandise, finishing, dyeing and processing of fur skins. A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna, Pest, Leipzig 1891, pp. 73-75.

- ^ Spilogale gracilis on Animal Diversity Web, accessed December 10, 2010.

- ^ A b John O. Whitaker, Jr .: Mammals of Indiana: A Field Guide . Indiana University Press, July 30, 2010, ISBN 978-0-253-22213-8 , p. 1, (Retrieved November 23, 2011). (engl.)

- ↑ www.dgif.virginia.gov/wildlife/information ( Memento of the original dated December 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Accessed August 22, 2012

- ↑ a b c d e f Fritz Schmidt : The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer Verlag, Munich 1970, pp. 292-299.

- ^ Christian Heinrich Schmidt: The furrier art . Verlag BF Voigt, Weimar 1844, pp. 68-69.

- ^ Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 4. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 200 ( → table of contents ).

- ^ Wilhelm Harmelin: Jews in the Leipziger Rauchwarenwirtschaft . In: Tradition - magazine for company history and entrepreneur biography , No. 6, 1966, Wilhelm Treue (Hsgr.), P. 282.

- ^ H. Werner: Die Kürschnerkunst , Verlag Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, Leipzig 1914

- ↑ Paul Cubaeus, Alexander Tuma: The whole of Skinning . 2nd revised edition, A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna, Leipzig 1911. pp. 79–80, 369–373.

- ^ Walter Fellmann: The Leipziger Brühl . VEB Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1989, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ a b Editor: Polecat, marten, otter and skunk remain marginal ranges . In: Pelz International , Issue 10, Rhenania-Fachverlag, Koblenz October 1948, p. 58

- ↑ a b c Editor: The Skunksfell . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 25, Leipzig, March 30, 1935, p. 1.

- ↑ a b c d e Alexander Tuma jun: The practice of the furrier . Published by Julius Springer, Vienna 1928, pp. 28, 30, 182–185, 270–272.

- ↑ Friedrich Kramer: From fur animals to fur, Arthur Heber & Co, Berlin 1937, p. 79

- ^ Ernst Kreft: Modern working methods in the furrier trade , 2nd improved edition. Fachverlag Schiele & Schön, Berlin undated (the first edition appeared in 1950), p. 44

- ^ Heinrich Schirmer: The technique of the skinning . Verlag Arthur Heber & Co., Leipzig 1928, pp. 192-210

- ^ A b David G. Kaplan: World of Furs . Fairchield Publications. Inc., New York 1974, p. 252.

- ↑ a b Author collective: Der Kürschner. Technical and textbook for the furrier trade. 2nd revised edition. Published by the Vocational Training Committee of the Central Association of the Furrier Trade, JP Bachem Publishing House, Cologne 1956, p. 143

- ^ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: Das Kürschnerhandwerk. III. Part: The processing of the skins. Chapter Skunks. - Civette . Vol. 2, self-published, Paris 1902, p. 16.

- ↑ Paul Schöps u. a .: The material requirements for fur clothing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVI / New Series 1965 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin a. a., pp. 7-12. Note: The information for a body was only made to make the types of fur easier to compare. In fact, bodies were only made for small (up to about muskrat size ) and common types of fur, and also for pieces of fur . The following dimensions for a coat body were taken as a basis: body = height 112 cm, width below 160 cm, width above 140 cm, sleeves = 60 × 140 cm.

- ^ Otto Feistle: Rauchwarenmarkt and Rauchwarenhandel. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1931, p. 15, 28. Table of contents .

- ^ Emil Brass: From the realm of fur (1911)

- ^ Frank Grover: Practical Fur Cutting and Furriery . The Technical Press, London 1936, p. 109

- ↑ Jonni Wende company brochure, Rauchwaren en wholesale, Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Leipzig, New York, August 1925, p. 10

- ^ Kurt Nestler: Tobacco and fur trade . Dr. Max Jänecke Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1929, p. 106

- ↑ 2. Source: Leipzig auction prices - results from June 2, 1939 . S. [?] + 149. Title and edition of the tear out from a specialist journal cannot be determined

- ^ Hermann Deutsch: The modern skinning. Manual for the furrier, dyer, bleacher, cutter and garment maker . A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig, 1930. p. 66.

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, p. 66.

- ^ Arthur C. Prentice: A Candid View of the Fur Industry . Publishing Company Ltd., Bewdley, Ontario 1976, p. 274. Secondary source also Fish and Wildlife Service; BDC stands for [?].

- ↑ NAFA Fur-Prices (Eng.) Retrieved August 28, 2012