Skinning (skinning)

The skinning or the skinning technique describes a working method of skinning , the production of desired skin shapes and a desired skin appearance by lengthening the skin at the expense of the width by means of V- or A-shaped cuts.

Sewn together again, narrow strips are created in the length of the garment to be produced, which has a particularly flowing drape as a side effect. Complicated strip guides can also be implemented with this. The waistline of a coat is additionally emphasized by the stripes, which are also waisted. In the period from World War II to the end of the last century in particular , an estimated 90 percent of mink coats were left out. For the newly added wholesale markets in Asia, including Russia, mink in exuberant processing is still a main item in fur fashion today.

Probably every suitable type of fur has already been worked in exuberantly. The main types of fur used for this purpose are, along with the frequency of their use, the species of marten , first and foremost the mink, followed by the tree and stone marten , otter , sable , previously also skunks , etc. Unsuitable are spotted skins such as skins that are no longer used today of ocelot , leopard and jaguar , very small and flat-haired pelts like hamsters or weasels . In skins with hair that is too short or with hard awn hair and little undercoat, the cuts remain visible, especially with seal fur . In addition to the respective fashion, the question of economic efficiency plays a decisive role in the decision whether the skins are left out in a labor-intensive manner or just stacked on top of one another, the added value must correspond to the additional effort. Often skinned skins were, for example, nutria , muskrat and rabbit fur until, due to the considerable rise in wages in the Federal Republic of Germany, in the 1980s, skipping these cheaper types of fur became less and less worthwhile.

The "invisible" omitting only geradhaarige fur species whose hair is long and flexible enough are primarily the by sewing with fur sewing machine with a monofilament Überwändlich - chain-stitch trap -Naht the leather basic Haarverbiegungen occur until the skin surface. In addition, there should be no extreme hair length and hair color differences. The polecat fur has the most vividly shaped and colored coat, which places very special demands on the furrier, especially when it is processed in an exuberant manner.

Variants include letting in , which is used less often , has the opposite effect, the fur becomes shorter and wider, and letting out round .

General, history

Before the development of inlet and outlet, the shape of a fur was changed only by stretching it in length or in width. Larger lengths or widths were achieved exclusively by sewing together several skins or skin parts.

The Leipzig fur trader Heinrich Lomer wrote in 1864: “The Chinese are at the fourth and almost the highest level [of fur processing]; They know how to prepare their sables, squirrels, cats, foxes, lynxes and tiger skins well, the composition of the skins is exemplary and orderly; they understand what is known as letting out and letting in the skins with the furriers. For example, you can make a sable fur as long or as wide as it was by making various incisions without noticing the incisions and seams on the hair side of the fur. "

If you follow the master furriers and trade teachers Malm and Dietzsch, then shortly after 1850 in Germany it was the furrier Leberecht Giese from Leipzig who cut a "lateral tongue" for the first time (on the edge of the skin) and thus the development of not only today's "tongue pulling" (see under → Attaching ), but also knocking out skins. The journeyman worked for the Starke company in the “Zur Goldenen Kanne” office building, Richard-Wagner-Strasse, on the site of today's “Seaside Parkhotel”.

Against this, however, is the fact that as early as 1837 for the master craftsman's examination in the Prince Diocese of Würzburg, among other things, it was required to omit a pine marten with twelve tongues the length of one cubit . Much earlier, in the middle of the 16th century, “omitting” is mentioned in the Würzburg master’s examination regulations, but in a text that is difficult for us to interpret today. A drawing from 1777 already shows the omission of a fur in the so-called “stair cut”. Elsewhere, the beginning of letting out is assumed to be rounding through individual cuts, the first use of which is believed to be in the 19th century. Already in 1883, Simon Greger describes how the missing length for a fur lining made up of four row heights is not supplemented by an unsightly, additional half row, but by leaving out the individual furs at every row height.

The furrier journeyman Wilhelm Schnell describes in his curriculum vitae that in a Viennese furrier, around 1905, the outlet seams were still sewn by hand. It was the year in which the Viennese furrier journeyman with the threat of strike enforced the 9-hour working day.

“We were 4 journeymen and 2 apprentices. During work we sat on small stools at long, narrow tables and sewed everything by hand. The two older colleagues had a lap board on their knees and cut to it. Since I could sew a fine seam, I was soon popular and could also purposes to help. Of course, I never got into editing. The weekly wage was 22 kroner for 10 hours of work. What I could steal with my eyes, I did, endeavoring to put myself in the good light, grateful for every grip that was shown to me. Feh, dewlap , skunks and sheared muskrat colored on mole was the fashion of the year. A mole muskrat jacket that was ordered was cut by the boss himself and left out the skins; I then had to sew it together myself. Weeks went by until the jacket was ready. "

It was only with the invention of the fur sewing machine (Balthasar Krems from Mayen in the Eifel that the basic construction is attributable to it, around 1800) and later introduction (after 1870) that it made economic sense to leave out entire coats, i.e. with a coat that was modified to the length of the coat or jacket , or even more elaborate, from one and a half, two or more skins previously cut into one another. At the Paris World Exhibition in 1900 , Révillon Frêres showed the first large pieces made of exuberant mink skins, including a floor-length coat made of 164 Canadian mink skins and an otter skin . However, these parts were still entirely hand-sewn, which required a working time of 1400 hours for the seamstresses alone. The fur sewing machines, driven by foot pedals, initially caught so much fur in the seams that they could not be used for finer work, especially not for sewing the narrow outlet cutting strips. At that time there was probably still a lack of “trained seamstresses”. Against this assumption, however, the fact that Revillon Frères exhibited a blanket made of 22,000 mink tails at the same time, " gallonized with fine leather and sewn with the machine [!]". The beautiful and exact work aroused "all-round admiration".

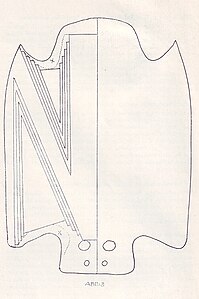

The American furrier and specialist author Samuel Raphael tried in vain to find out where the origins of omission can be found. However, he came to the conclusion that the commercial use of the work technique began in the early 20th century with the skunk fashion. Around 1916, exuberant mink coats were also offered in the USA. He reported from Leipzig that around 1908, mink coats were made from two skins instead of 2 ½ or 3 skins stacked on top of each other, the rest had been left out with a few double zigzag cuts ("N"). Another theory, which Raphael himself thinks seems somewhat legendary, his father often told him. After that, a long time ago, son Samuel remembers in 1948, French furriers accidentally cut mink skins in various places. When trying to repair these skins, the furrier made mirror-like cuts on the other half of the skin and had them sewn. He found that these seams could not be seen from the hair side. According to this tradition, he recognized that by changing the cutting angle when sewing, a hide can be lengthened. Today almost all types of fur used for this purpose have been processed in a skilful manner, but the working technique is mainly associated with the zoological family of marten, and especially with the marten-like mink. There is much to suggest that the omission developed slowly, but ultimately it remains uncertain whether it was not the idea of a single furrier.

The decision to leave skins all over for an item of clothing is not actually made in order to lengthen the skin; this is easier and, above all, cheaper to achieve by assembling it in a checkerboard manner. It is the harmonious stripes that underline the model, in contrast to the rustic look, which is rectangular, next to each other and sewn on top of each other, that prompts the designers to do this. At the beginning there was still a certain fear that the customer might consider a coat that he considered to be made of pieces to be less valuable, but the technology quickly caught on in the USA, as the high effort was worthwhile, especially with the more expensive types of fur. Originating in America, the fashion of exuberant furs came increasingly to Europe after the Second World War, delayed due to the war. The furriers tried practically all types of fur, more or less suitable, from the curly Persian to the smooth-haired seal, in which every cut is visible.

Sewing with the fur sewing machine requires great manual practice and skill. The most efficient way of brushing the fur hair is with the thumb or by means of a blower on the machine, otherwise with the brush, a pointed steel pen, nowadays mostly connected with tweezers (brushing tweezers). This work is carried out in larger furriers and in industry by specialized workers. In Germany it was fur seamstresses who were paid less than their male furrier colleagues from the start. In the 1960s, Greek sewers came to Germany from the fur sewing region around the city of Kastoria , they brought a different sewing technique with them. Instead of holding the hair piece by piece away from the seam edges with the scraper, you sit bent over on the side of the sewing machine and use your thumbs and blow the hair back to the side of the fur. This allows you to sew through an outlet cut almost without taking off. Within a short time they had taken over the local mink sewing shop. Larger companies had "their Greeks" in their own business, others outsourced the sewing of the mink strips as wage labor.

Raphael called the late 1940s as a fur species that were almost always left out at the time in America: sable, mink, marten, Kolinsky , Bassa Risk , foxes , shaved beaver , fine gray Naturpersianer , Lyraskunks , and for more sophisticated clothing that otherwise cheaper species Nutria, opossum and muskrat. That the method of putting mink on top of each other could ever recur, he considered extremely doubtful, as unlikely as if the "chick returns to its egg".

Towards the end of the 20th century, fur fashion was becoming more and more sporty, away from the elegant go-out coat and towards clothing that was as suitable for everyday use as possible. The skins were placed on top of each other more often and left out less often. Since then, significantly fewer exuberant furs have been produced and offered in Central Europe, the outlet clothing was largely produced in the furrier town of Kastoria, which also supplied other world markets, and many Greek fur sewers returned to their homeland. The previously exceptionally high fur sales in the post-war period, especially in the Federal Republic of Germany, fell significantly, the main sales for fur and also the production shifted to the newly economically developing countries of Asia including Russia, especially to China, but also to other countries of the Continent. For Kastoria, fur production and trading is still an important economic factor, albeit several times less than between 1950 and before 2000.

Suffragette in an exuberant beaver coat (around 1923)

Actress Pola Negri in a cross-processed, exuberant sable coat (1927)

workflow

Mink, like the other species of marten, come round to the furrier, not lying flat and cut open towards the front paws, unless they have previously been subjected to special types of refinement that require a flat fur (for example veloutier ). For the production of jackets or coats they are sorted, matching according to color and hair length next to each other, the skins suitable for collars, cuffs etc. are marked. In the next step, cut skins are attached to the belly side , which means that any imperfections in the hair or leather are repaired. Then they are stretched smoothly in the moistened state, possibly according to templates in the same widths and the resulting different fur lengths. After tearing off the dried pelts, the middle of the pelt and the cross on the leather side are marked, the cross is the flat-haired and darker part between the front paws. Front and rear paws are cut off and sent for separate recycling (see → Fur scraps ), possibly also the forehead piece up to behind the ears.

For the detailed production of a fur part, the individual stripes are drawn in their calculated width on the pattern. The connections to the sleeves should be harmonious, in the shoulders the side seams and grunts of the back and front parts should come together exactly. For fur stoles, multi- fur collar shapes and the like, the fur sizes must be reduced or enlarged according to the specifications of the pattern ( transfer ) before leaving out .

The work steps and the actual discharge work differ considerably depending on the company, employee and model. In the simplest form, the seamstress cuts the skins freehand after he has calculated how many outlet cuts he needs for the required strip length and moves the cut strips according to his experience or according to markings that he draws on the cut ends. In the most complex, but most precise form, the furrier calculates the back distance for the individual cuts and marks it for the closer. The shape of the skin, the pattern and the different stretching behavior within the skin are included in the calculation.

The skins can either be cut with a skinning knife after the cutting legs have been drawn in, usually with the help of an outlet roller. Most furriers do not completely separate the cuts when cutting by hand at the cut ends and in the middle of the fur, so that they do not get mixed up, the sewer then cuts or tears off the next cut strip to be sewn. Or the skins are cut into individual cuts with a skin cutting machine. Most cutting devices require the skin to be cut in half lengthways, in the grot.

In 1957 the sewing time for a mink by an American mink sewer "top class" was named 35 minutes. However, the important information about the fur size was missing (female mink are significantly smaller than male) and about the cutting width. Nowadays, very fast sewers need about half an hour to more than three quarters of an hour for a fur in some of the larger bred animals.

If the skins are sewn to the correct length, they are slightly moistened, the seams are pressed flat with the seam roller or the stretching wood and the skin is stretched a little flat. The side corners that arise when the product is let out are straightened with scissors and then the loose cut hair is removed in the refining barrel . As a rule, the sewn strips are checked again on the sorting plate while hanging, in particular for their sheen and, if necessary, rearranged. After the strips have been marked for the sewer lying on the pattern, they are sewn together. It is particularly important that the conspicuous cross sections come exactly next to each other.

A strip of leather or textile (previously often a velvet ribbon), about 4 to 6 millimeters wide, is often sewn between the fur panels. The idea of applying this to mink originated in the USA. Depending on the material and the opinion of the client or furrier, coats, jackets, but also stoles, with or without stripes are made. Proponents point out that this makes the strip effect more effective. It also reduces the weight and reinforces the already soft and flowing drape of the garment. And perhaps not entirely insignificant - it saves more than a more expensive mink fur. However, the sewer has to cope with about two thirds more seam length when sewing the fur strips together (the galons usually start below the flat cross section and end above the hem) and there is a risk that the longitudinal seams break and become visible when worn in the hair. Today, processing with a galon strip between the longitudinal webs is predominantly preferred, even for high-quality coats. The sleeves often remain ungalonized because of the risk of the galons becoming visible.

Other operations include rolling out the longitudinal seams of the sewn-together fur strips, the purposes and subsequent matching according to the respective pattern, tying the edges, applying the inlays, sewing the individual parts together, hitting the edges and sewing the lining as well as a finish of the finished Fur.

- The omission of mink skins

Skipping techniques

| Possible variants of the color image design | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cut type | Color image design of the fur strip (hair stroke to the hem) |

||

| Basic cut type | Reverse cuts |

Hem it |

On the neck hole , it is |

| A-cut | without returns | dark | bright |

| Returns at the pump | dark bright | bright | |

| Returns on the head | dark | light / dark | |

| on the pump and head | dark bright | light / dark | |

| V-cut | without returns | bright | dark |

| Returns at the pump | light / dark | dark | |

| Returns on the head | bright | dark bright | |

| on the pump and head | light / dark | dark bright | |

The changes in fur caused by cuts can be divided into three groups:

- As a single cut , when the fur should only be changed slightly in its shape.

- As a cutting group to professionally execute a slightly larger change in shape. Several individually placed cuts usually mark more disturbing on the hair side than a group of closely spaced cuts.

- As a comprehensive cutting system in which the entire surface of the fur is changed in its shape and also in the appearance of the hair body. While the small hair length and hair color gradations resulting from individual cuts can already appear “unbearable” to the eye, “it is, however, possible that such 'errors' do not have a disruptive effect in the comprehensive cutting system, as they occur in masses and practically evenly over which the entire fur surface is distributed ”(or the entire item of clothing).

If the structure, color and shape of the skins do not place any conditions on the choice of the type of cut, the changes in the hair appearance caused by the omission can be used for the design. The resulting image is materially from the uncut fur ends in the head and Pumpf influenced, with the returning sections can potentially unwanted light or dark strip ends are, for example, in the neckline and shoulders and hem, prevented (see table at right).

As part of a redesign, subsequently rounded strips of mink

- With rounding , a rounding of the skin is achieved at the same time as lengthening or shortening the skin. It is very often used for strongly rounded collar shapes. When rounding, the cuts usually end in the middle of the skin, they are not connected to the cuts on the opposite side of the skin. The back removal is only carried out fully in the cut ends, the resulting difference in distance is observed . By leaving out the later longer skin side and admitting the inner side, the desired roundness is created, whereby the outside of the skin becomes narrower and the inside widens. Weaker curves are usually not taken into account when sewing, they are achieved by simply stretching or unclamping (purposes) the moistened fur or strip of fur.

- By pinning , pinning , strip shapes that cannot be calculated in practice, with corners, several curves, etc., can be precisely reproduced. The outlet strips are individually attached to the cutting pattern recorded on a base with pins and marked with many markings for the sewer. As a result, longer cut edges are created towards the inner rounding, which the sewer must adhere to, as with rounding.

- When skipping crosswise, the cuts are made crosswise, at right angles to the middle of the skin. As a rule, with this seldom used technique, the cuts for the adjacent jacket or coat strips are shifted one to the left and the next to the right in order to achieve a harmonious, mirror-image image and a suitable transition.

- Individual stair cuts are occasionally used to let in or out curly ( Persian ) or moiré goods; instead of a straight cut, a step-shaped cut is used, which is less perceptible to the eye with curly fur. The cuts can also have a jagged or wave shape, they are shifted by a box, jagged or wave when sewing, possibly even by two.

- Incision , repositioning : Since a small skin, especially when making the coat, may result in an undesirably narrow stripe, or the cuts are marked too strongly because of the large offset, in this case stripes are made from more than one skin. The skins are divided into various pieces with cross sections and put together to one piece according to the color of the coat and the length of the hair, a job that requires great experience and care. If it does not succeed, a noticeable, so-called "fir tree" is created on this cross seam after it has been left out on the hair side. It may be necessary to partially divide the horizontal strips into strips up to 5 millimeters wide. Particularly difficult to sort and cut fur types are, for example, polecat, sable, tree and stone marten. Repositioning describes the equalization of area between two (identical) skins, the enlargement of one skin to the disadvantage of the other.

- By shifting the fur strips, a mirror-like image of the fur is created. In each case one longitudinal half of the fur strip goes into the left, the other half into the right half of the jacket or coat.

- Since skins often fit together better in the flatter grot than in the sides, the stripes can be shifted within oneself . The half strips of fur are now sewn together with their own fur sides instead of grunting.

- At the Grotzengabelung , the fur is divided into two stripes, for example in the waist, in order to then achieve a special look in a wide part of the skirt downwards.

- When cutting at the cutting angle ("diagonal cutting"), two or more stripes are created from one hide, for example for the shorter sleeves. When cutting 1: 2, every other cutting angle is removed and sewn together to form a separate strip. At least theoretically, more stripes are conceivable, but in practice this will rarely result in an acceptable coat appearance.

- Falling refers to the processing of a fur with the hair beat upwards. When falling in-on-oneself , the outlet cutting strips are reversed in the order: the first strip comes under the second, the third, the fourth and so on. The hairline then points towards the head, contrary to the naturally grown fur. If the fur is now not overturned, but worked with the hair direction down, the head section is down and the striking cross mark is in the skirt part of the garment above the hem.

- The time-consuming rushing can be used to improve the otherwise unsightly connection between the head of the fur and the end of the fur, in particular within a fur for a cuff. To do this, the head and the end of the fur are divided into small horizontal strips before they are left out, until the middle section is reached and both strips have the same hair length. The greater the change in hair length within the coat, the narrower the stripes must be. Every second horizontal stripe is removed and sewn together again in reverse order, the head stripes on the head and the pump stripes on the end of the fur. At the ends of the fur there are now stripes with a similar hair structure.

Outlet calculation

Instructions for experts for the largely exact percentage outlet calculation can be found here (author master furrier Rudolf Toursel ):

The coat of a fur varies over its surface in three directions, in length, width and height, more or less depending on the type of coat. These conditions are of crucial importance for making cuts in skins. In addition to the color changes, the change in length of the shorter, differently colored under hair is of particular importance. It is the essential factor for the greatest possible return distance. If it does not sufficiently cover the undercoat of the adjacent cut due to excessive displacement, the outlet seam on the hair side becomes visible to the eye. - A special case are curly pelts, such as the Persian fur , which has no undercoat in addition to the special shape of the guard hair.

Every sewing in fur leather has an effect on the hair side. At the base of the hair, the hair bends and thus shortens, and it is also pushed out of its natural hair direction. From which “steps below a certain size” a cut really starts to become conspicuous has not yet been determined. The obvious assumption that the cut marking would be lowest if a coat were completely uniform in hair length and color is wrong. Apart from the fact that these skins do not exist, the cuts are less noticeable in a restlessly structured and patterned coat. Only the inequalities caused by the mutually shifting of the cut edges, which allow the cut to be marked more strongly if the back distance is too great, cause additional uncleanliness on the hair side. In general, seams and hair length differences are less visible in bleached white and black pelts, otherwise more in light hair than in very dark hair (shadow effect).

The greatest change in hair length and mostly color change in a short distance is shown in the cross profile of a coat. As a result of this structure, the more obtuse the cutting angle, the more marked a cut, the more the angle approaches the horizontal. In addition to other types of fur, the hair structure of the marten-like changes particularly abruptly around the cross, the area between the front paws. The fur strips that cut through the cross should therefore usually only be moved a little, and possibly not at all, regardless of the pattern. The type of cut to be used is primarily determined by the hair profile and appearance, and less importantly by the shape of the coat. It also serves to achieve certain visual design effects in the finished garment.

The fur that can be changed by omitting is naturally not formed uniformly. The head area is narrower than the residual fur, which often widens conically towards the back. The cross section is particularly narrow because the front paws are not cut out here, but cut open to the sides. As a result, a piece of the peritoneum falls off together with the paws at this height of the fur. This affects not only the width, but also the appearance of the fur. All conditions must be taken into account when calculating the outlet in relation to the new shape to be achieved and for a visually harmonious effect, in addition to the specification of a section marking that is as invisible as possible.

- Some technical terms

As Grotzen in the fur trade of fur back is referred to, it is usually long gran niger and darker than the rest of the body fur; the belly of fur is called dewlap , in the case of cut fur it is the sides . The pump is the rear end of the skin, in front of the tail . Rauch is a fur with thick, not tightly fitting hair.

- V-cut , A-cut , extended V-cut ( M-cut ), extended A-cut ( W-cut ), stair cut :

- Each with the fur head on top, V- and A-cut (two-legged), M- and W-cut (four-legged), extended M- and W-cut (multi-legged) or step-shaped cuts.

- Mainly the V-cut is used. The shorter hair is pulled under the longer hair, which significantly reduces the need to mark the cuts compared to the A-cut. The A-cut creates a stronger profile in the middle of the coat by clashing the hair, the stripe effect is more pronounced. From this it can be generalized that the A-cut is favorable for flat in the middle of the coat, the V-cut for skins with a distinctive, strong hair profile.

- With extended cuts, the resulting thigh tips are usually placed in the color and smoking border, but it is better to place them next to the longer-haired half of the coat. The cutting angle and the lateral displacement are reduced by the extended cut.

- Missing length :

- The difference between the length of the fur and the stripe (pattern) length to be achieved.

- Number of cuts :

- The number of cuts in a hide that are moved.

- Cutting width :

- The shortest distance between two adjacent cuts. The cutting distance is the distance between two cutting tips on the middle line of the fur, the grot.

- The most common cutting width when processing mink is 5 millimeters, with finer processing four to four and a half millimeters. In 1972, the Strobel company stated that the smallest cutting width to be sewn was 3 millimeters for its model class 141-40.

- Back distance :

- The distance by which two strips of fur move against each other when they are sewn together.

- Average return distance :

- Determined by the furrier after familiarizing himself with the hair pattern. It results from the maximum back distance , the distance by which the two cuts can be shifted against each other without marking ugly.

- Seam loss :

- The area around which the fur is shrunk by pulling together and pinching the leather while sewing. A common but not very precise assumption is, for example, a loss of 10 to 12 percent with a cutting distance of 5 millimeters and a completely cut mink fur. It is recommended that you determine the actual loss by making a test strip. The seam loss depends on the number of cuts (on the cutting distance), the thickness of the leather, the thread size, the needle size, the tension set on the fur sewing machine (fixed tension = higher seam loss) and the skill of the fur sewer.

- Grinding , flamed cut :

- When cutting by hand, i.e. with a skinning knife, it is better to sweep the cuts at the ends by reducing the cutting angle than when cutting straight. On the sides of the fur with the hair lengths increasing rapidly towards the middle of the fur, the hair length difference is reduced, the cut marks less on the hair side. In the sides and in the middle of the fur, the grunt, there are fewer strong corners, the fur remains smoother or, if the edges are edged with scissors after sewing, there is less material loss.

- The flamed cut requires the furrier to be particularly aware of the hair pattern. It enables a constantly changing cutting width, for example in the flat head, the cross section can be left out earlier in a flamed cut than in a straight cut. The cuts can be made in such a way that the greatest shift occurs in the similar hair structures. The undesirable waist effect is reduced by a more favorable material distribution. These apparent advantages are weakened by the fact that the small inaccuracies that occur during straight cutting need by no means be detrimental to the eye.

- Galoning , also feathers in connection with skipping:

- Galoning refers to the interposition of strips of leather or fabric in hides in order to enlarge the area or achieve special effects. When leaving out, a strip of fur and a strip of galon are sewn together alternately. As a result, the cuts become visible on the fur side as a feather -like or herringbone-like pattern , at least with short-haired types of fur .

- some rules

- The smaller the distance from the back, the narrower the cutting strip, the more acute the cutting angle, the smaller the cutting mark.

- The more obtuse the cutting angle, the stronger the cutting mark, but more cuts (and thus less marking due to smaller back distance).

In addition to the percentage outlet calculation, the basis of which is the different lengths of the cuts in a skin, there are a number of simplified, usually less precise calculation methods. Since the fur leather usually has a very good tack, these will also lead to a sufficiently good result in daily practice with the appropriate routine. One of the variants is to set only the upper and lower fur width in relation to the upper and lower stripe width to be achieved instead of the cut lengths. Converted to the average back distance results in the back distance for the first and the last cut. By connecting the two markings over the entire cut area, the sewer receives the different indentations for the individual cuts. The narrower, usually more equally wide head section is usually charged extra, as are the shortened end cuts in the head and pump.

Let in

The fact that the inlet is much less used, the opposite of the outlet, widens and shortens skins at the same time. The cuts should not end too close to one another, otherwise the width will not be evenly distributed.

Auxiliary equipment and machines

General equipment or skinning machines that are not only used for processing skinned furs are the fur sewing machine , the lauter and shaking barrel as well as the beating machine for removing the cut hair, mechanical purpose guns (staplers) for preparing the skins and tensioning the fur parts, ironing machines and steam machines . Steamers for straightening hair and others. In addition, a number of devices and machines have been specially developed for venting.

Outlet rollers

Outlet rolls are used for the efficient, clean and uniform recording of the outlet cuts for cutting with the skinning knife. The rolls, which are available in different cutting widths, are exchangeably inserted into a holder with a handle and a paint roller, a spring mechanism presses the roller against the paint roller soaked with pagination paint. For a comprehensive cutting system, the moistened hide must be stretched smooth beforehand, or at least stretched smooth, whereby the leather also solidifies. For easier sewing, the fur leather is often additionally stiffened with a laundry starch.

- With the simple roller , the cutting angle can be determined individually. For this purpose, the first and the last cut are recorded on the skin as a guideline, for this purpose a parallel measuring device can be used. For more precise application, a guide rail can be used with some constructions. The unprocessed half of the skin is best covered with an aluminum foil.

- With the angle roller , the cuts are applied to both skin halves at the same time, there is no need to record the cutting angle beforehand. In addition to the various cutting widths, it is available with several cutting angles.

Outlet cutting devices and machines

It is important that the hair is not injured when cutting. For the outlet cutting machines that are currently mostly in use, the skin must be divided in the middle of the skin, the grot, before cutting.

- The first, still mostly used machines cut with a high-speed rotating knife shaft driven by an electric motor (with a cutting width of four millimeters there are 70 knives). For technical reasons, the shaft, which can be adjusted in the cutting depth, can only be changed between twice the cutting widths (for example between 4 and 8 millimeters), the usual basic cutting widths are 4, 4.5, 5, 6 and 7 millimeters. For cutting, the skin half is inserted by hand into the switched-on machine, if possible with the head part first, then guided by a needle roller under the knives and removed by hand on the opposite side, being careful not to grasp the cut strips again . The needle roller and a rubber roller, which transport the skin, are operated with a hand crank. At the same time, a piece of cardboard is carried out on the base plate of the work table, on which the cut fur comes to rest. Hides that are wider than the knife shaft must be cut in several sections. The knives need to be sharpened from time to time.

- The "Vismatic" cuts the fur without having to grunt it. In the middle of the fur, the cuts remain connected. The drive is pneumatic.

- A flatbed cutter, patented by the Belgian Germain Martens in 1994, also cuts the skins without the skin being split in the grot, but without a mechanical drive. As a further specialty, the cuts in the flatter head section of the mink fur are narrower than in the smoky remaining fur. The knife's sharpness has been reported for cutting over 2000 skins. About 30 of them were sold, mainly to Korea and Hong Kong. In contrast to his Galoniergerät, which went on sale in 2013, it was no longer produced despite its innovative design.

Outlet machine

The outlet machine is a construction by Pfaff that manages the entire process of cutting into outlet strips, moving the strips and sewing them back together in one automated operation. Because of the high price, it was probably only built in small numbers (from 1983).

Fur edge trimming device

The fur edge trimming device was an accessory to the fur sewing machine. It was also presented by Pfaff at about the same time as the outlet cutting machine. With it, the skins that were left out were automatically cut off when the left out strips were sewn together, usually a time-consuming and uncomfortable manual work. However, it does not appear to be known whether the device went into large-scale series production.

See also

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c d e f Hans Quaet-Faslem, Martin von Schachtmeyer: Pelz 1: Introduction to the technique of changing fur through cuts. 3. Edition. Central Association of the Furrier Handicraft (publisher), Bad Homburg, 1985.

- ^ Heinrich Lomer: The smoke goods trade. History, operation and commodity knowledge . Leipzig 1864, pp. 54-55.

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, p. 92.

- ↑ Item 3 of the master craftsman's regulations, in the translation by Paul Schöps: "Let out a marten" as follows: should make 3/4 of a length even so that you can see the hair, and he should also remove the dirt from his aigen feathery the marten without harm, full half a mile long, and four-part braid. Ess should also be stained by the same, nothing left over, and nothing left behind. He is also supposed to bid the schwerkh to the caps and the marten. and prepare, is never right. "

- ↑ Dr. Paul Schöps, manuscript dated February 17, 1978: Meisterstücke . Pp. 3-4. G. & C. Franke collection

- ↑ Denis Diderot and Jean de Rond d'Alembert: Encyclopédie, ou dictionaire raisonne des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Figure 17 Fourreur, Coupe de Peaux. Paris, 1762-1777.

- ↑ Simon Greger: The furrier art . 4th edition, Bernhard Friedrich Voigt; Weimar 1883, pp. 188–190, 198 (130th volume in the series Neuer Schauplatz der Künste und Handwerke ).

- ^ Wilhelm Schnell: Wilhelm Schnell, Berlin . In: The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 4. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 291 ( → table of contents ).

- ↑ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: The furrier craft. 1st year No. 1 + 2, October / November 1902, self-published, Paris, p. 4.

- ^ Jean Heinrich Heiderich: The Leipziger Kürschnergewerbe . Inaugural dissertation at the philosophical faculty of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität zu Heidelberg, Heidelberg, 1897, p. 101.

- ↑ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: The furrier craft . 1st year, No. 1 + 2, self-published, Paris, October-November 1902, p. 31.

- ^ A b c Samuel Raphael: Advanced Fur Craftmanship . Fur Craftmanship Publishers, New York 1948, pp. 32-36, 136 (English) .

- ↑ a b Hans Quaet-Faslem: Comparative about the mink omission. In: All about fur. Issue 12, December 1957, pp. 14-16.

- ↑ Arthur Samet: Pictorial Encyclopedia of Furs . Arthur Samet (Book Division), New York 1950, p. 141 (English).

- ↑ a b c d Author collective: Manufacture of tobacco products and fur manufacture . VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, 1970, pp. 344–398.

- ↑ Without mentioning the author: J. Strobel & Sons - Rittershausen . In: Rund um den Pelz International No. 6, June 1972, p. 16.

- ^ Author collective: Der Kürschner. Technical and textbook for the furrier trade. 2nd, revised edition. Vocational training committee of the central association of the furrier trade (ed.), JP Bachem publishing house, Cologne 1956, pp. 28–67.

- ^ A b Hans Quaet-Faslem, Martin von Schachtmeyer: Pelz 3: Process for shaping fur. Central association of the furrier trade (publisher), Bad Homburg 1977.

- ↑ Rudolf Toursel : Working with the fur-cutting machine. November 1964.

- ^ Homepage of the Germain Martens company: About us ( Memento from November 25, 2015 in the Internet Archive ). Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ↑ GM Fur Cutting Systems: The GM flatbed cutter for mink skins . Company prospectus, undated.

- ↑ Cutsewmat. Pfaff brochure no. 296: We won't put a louse in your fur…. Kaiserslautern April 1983.

- ↑ Without the author's details : Again something new from Pfaff: After the automatic skin outlet, now the skin edge trimming device. In: The fur industry. Issue 4, April 7, 1982, p. 182.