Polecat fur

The polecat fur was used in former times allegedly only by "allergemeinsten" people, old paintings, however, seem to refute that. The European polecat , also known as “stink marten”, “stinker” or “ratz”, was often afflicted with an unpleasant smell: “Like the polecat, they stink badly and strongly”, it says in an old hunting book. Today's dressing has succeeded in completely eliminating this smell from the fur.

The fur trade uses the fur of the European polecat, steppe elk and tiger elk . The ferret , the domesticated pet form of the polecat, only has a certain significance in the feral form of New Zealand , it is similar to the European polecat. The English word fitch describes the ferret in some countries, but it is mainly used as a name for the ferret skin. In the 1970s, these skins, which had actually been traded for a long time, were touted as a novelty in specially selected breeding and for the first time in larger numbers. Scottish breeders declared the “Fitch” they bred to be a cross between polecat and ferret.

In addition, the trade knows the Virginian polecat fur, the fur of the American fishing marten that is not discussed here . The skunk- like zorilla , also called bandiltis, is a species of predator from the marten family that lives in Africa and is also not one of the fur types discussed here. The North American black-footed polecat , which has always been quite rare and only occurs in very small numbers, is completely protected, skins of this type were not previously recorded by trade.

European polecat

The European polecat, also known as "black polecat", "forest iltis" or "land iltis", is distributed over the whole of Europe, with the exception of Ireland , northern Scandinavia and Russia . The species was introduced in New Zealand.

The fur of the male animal is about 34 to 46 (very rarely up to 48) centimeters long, that of the female 29 to 39 centimeters. The length of the tail is about 12 to 18 centimeters in the male and 8 to 15 centimeters in the female. It is a so-called "open coat" because the dark upper hair does not completely cover the light undercoat. This makes the fur appear as if covered by a thick, dark veil. The closer the awns, the darker the fur looks. This makes the polecat one of the “wrong” colored fur animals, that is, one of the animals in which the top is lighter than the bottom. The head is reddish gray or reddish brown, the muzzle is whitish, as is the area behind the eyes and the tips of the ears. Black spots around and in front of the eyes result in a mask-like drawing of the face. Neck, chest, legs and tail are dark, mostly brownish-black in color. The colors vary a lot, from white and whitish-gray to yellow, orange to red-yellow. Not infrequent are flavisms , so-called “scrambled eggs” or “honeysuckle”, which are completely monochrome, bread or honey yellow. These are mainly found in southern Europe. There are also dark red to brown shades of color, so-called “frog turtles.” The hair is long, fine to coarse, shiny and not particularly dense. The fur of the polecat species is the same in summer and winter, but the summer fur is dull, grayer, significantly thinner and shorter-haired. Hair changes in spring and autumn.

There is an average of 8,500 to 9,000 hairs on a square centimeter. There are 20 wool hairs for every guard hair. On the back, the wool hair is 25 millimeters long. The protruding guard hairs on the back are about 45 millimeters long. In summer the awns reach a maximum length of 35 millimeters.

The durability coefficient for the European polecat is given as 30 to 40 percent. When the fur animals are divided into the fineness classes silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the polecat hair is classified as fine.

The best polecat hides come or came from Eastern Europe , as well as from Northern Germany, the Black Forest , the high plains of Bavaria, Austria (Styria), Switzerland , Holland and Denmark . An encyclopedia of goods from 1814 mentions Turkey , especially Anatolia , “[...] a very fine and precious type of these skins, which are completely black with hair and feel soft as silk. They are very much sought after in the Orient for fur ”.

In 1988, Jury Fränkel ’s Rauchwaren -Handbuch stated the estimated annual production of 500,000 pelts .

The International Union for Conservation of Nature ( IUCN) has rated the European polecat in the Red List of Endangered Species as Least Concern . The Federal Republic of Germany places him in category V and thus on an early warning list. Twelve countries in Germany rate from Category V to predominantly Category 3 ( endangered ) to Category 2 ( highly endangered ). Austria and Switzerland list the European polecat in the national red lists with category 3 ( endangered ). The Bern Convention of the Council of Europe protects the European polecat in Appendix III of the agreement and declares it to be a wild animal in need of protection that may be used in exceptional cases. The European Union also assigns it this category by listing it in Annex V of the Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive (EC No. 92/43 or the amendment in Directive EC 2006/105).

trade

The game trade sorts the European polecat:

- Large winter hides 1: 1

- Well covered, but green leather 4: 3

- Small and female 2: 1

- Flat, covered, so-called rinds 4: 1

- Brack, damaged ad libitum

a) Russian tradition (standard)

- 1. Western

- 2. North-West

- 3. Central Russian

- Sizes and types:

- I. variety: full-haired, large

- II. Variety: full-haired, small

- III. Variety: half-haired

b) Hudon's Bay and Annings Ltd. , London and others:

- Origin: z. B. Poland

- Sizes: 65+, 55/56, 45/55 centimeters

- Varieties: I., II., III.,

- Colors: dark, medium, pale

The raw fur is delivered in bag form: hair partly inside, partly outside.

With the advent of fur farming in the 1920s and early 1930s, the breeding of polecats for fur purposes began. On a small scale, breeding found a certain distribution in Germany. Some of the breeding animals were even exported to America. In the Soviet Union , the breeding of the steppeniltiss ("Russian polecat") had been started. The attempts that were quite successful in terms of breeding were not granted any major and lasting economic success and breeding was discontinued. Today's revived breeds are obviously based on steppe iltissas.

Saint Sebastian with polecat trimmings (1510)

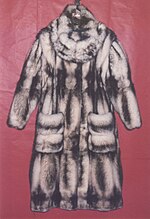

Polecat coat ( Gustav Klimt , 1916)

Steppe iltis

The fur of the steppe polecat , also called Eversmann- Iltis, is known in trade as "Russian polecat" or "white polecat". The steppe iltis inhabits large parts of Asia. The homeland of the steppe ice cream extends from the northern Urals through Siberia to the Amur , south through Manchuria to the upper reaches of the Yangtze and west over the Himalayas , Kashmir and the Altai Valley to the Caspian Sea . The best, silky and almost white skins come from Siberia.

The main difference to the Landiltis is the body size and the coat color. The steppe polecat is narrower and smaller than the European polecat. The designation "white polecat" is mainly based on the fact that the shorter guard hairs are less dense and thus the very light, pale yellow, sometimes almost pure white undercoat comes out, which then dominates the color. The coat length is about 35 to 40 centimeters. The tail is 14 to 18 inches long. The summer fur is yellowish to reddish, the winter fur gray-white or yellowish-white, sometimes almost pure white. Almost white polecats occasionally come from certain areas such as Petropavlovsk and Semipalatinsk . The throat, chest and legs of the steppe iltis are dark, often deep black. The color of the face is whitish. The dark areas on the bridge of the nose and around the eyes form a mask. A typical feature of the steppe iltis is the color of the tail. The back half is very dark, mostly brown-black, whereas the front half is as light as the undercoat.

The hair is long, fine and shiny. The winter fur is silky, soft and loose.

Chinese polecat

The Chinese polecat has a special characteristic. The neck is very flat, from the middle of the fur to the trunk it is rather smoky. The color is a little more yellow than, for example, the Russian white pillows. The fur is less suitable as a coat material, but looks quite good after dyed; it was used for cheap fur ties . A distinction is made between forest skins and mountain skins. The forest pelts are a little smaller than mountain pelts, a little more stocky in the hair and sometimes have a somewhat reddish color.

Trade, history

The Economic Encyclopedia by Johann Georg Krünitz reports on the use of polecat hides: “The Burata ( Buryats , members of a Mongolian tribe who dress in leather and fur) make sacks out of these skins to store their idols. The Chinese also use it for fur and buy the piece from the Russians for 11 to 15 kopecks; the tails, the piece for 2 to 3 cop .; and sewn sacks from such skins, from 6 to 15 rubles. The Mongols sell the Lenian polecat hides, 12 kopecks each. With us the piece costs 16 groschen. The hair of the polecat tails is used for the so-called hairbrushes of the Mahler. ”These sewn sacks are polecat hides sewn together to form panels, which were traded as semi-finished products in the form of an open-topped sack .

As early as the end of the 18th century, the steppe iltis was temporarily kept for fur production. Russian hunting officials set up special "Ratzkammern" in which they, in addition to noble foxes (e.g. cross fox ), fed smaller numbers of young kiltisse caught in the summer months until they were ready for fur.

The best skins of the steppe elk come from Siberia (Petropavlovsk, Semipalatinsk). They are large and silky, the undercoat is almost pure white. Saratow polecats are somewhat smaller, flatter and darker and are always delivered with the leather on the outside. Southeastern and Central Asian are smaller, have coarser hair, a yellow undercoat, and brownish upper hair. They are also pulled off with the leather side facing outwards.

The pelts from Mongolia , the Caucasus and southern Russia have a very yellow undercoat, the guard hair is more red-brown, the quality is coarser. The delivery takes place with the hair on the outside.

| The Russian standard differentiates according to origin: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petropavlovsk | Orenburg | Kazan | Siberian forest piltisse | Central Russian | Mongols |

| Semipalatinsker | Central Asia | Saratower | Siberian steppe polecats | Southeastern | |

| by types: | |||||

| I = full-haired | II = half-haired | ||||

| divided into slightly damaged, heavily damaged and brackish goods | |||||

In the past, a distinction was also made according to the type of preservation, i.e. whether the raw hide was naturally dried or the leather was rubbed with ash.

Today, skins of cultivated steppe iltiss are also sold via Scandinavia and Russia.

Tigeriltis

The distribution of the Tiger Tilt extends over southeast Europe and Poland as well as the countries on the coast of the Caspian and Black Sea to Mongolia and northern China . That means across Asia Minor , Kazakhstan , Iran , Afghanistan , Turkmenistan and Tajikistan .

The Tigeriltis can be found as Perwitzky in tobacco shops . Because of its speckling, it would be more aptly referred to as "Fleckeniltis" or "Pantheriltis". The fur has no tiger stripes, but is rather spotted like a leopard. The back color is light to dark brown with numerous yellowish spots. The underside of the body and legs are black. It has a wide white horizontal stripe above the eyes, and the muzzle and chin area are pure white. The wide ears are surrounded by a strip of white hair. From the nape of the neck run three whitish stripes, which are yellowish towards the back in western folk, but merge to form a white horizontal stripe in eastern folk. Elsewhere, however, it is noted: "This back markings are individually variable, geographical differences in the coat markings are hardly noticeable". The gray-brown undercoat is poorly developed. The tail is much bushier than the European Polecat and the drawing is very colorful, the tip of the tail is black. The fur length is 29 to 38 centimeters, the tail length 15 to 21 centimeters. In winter fur, too, the undercoat under the dense awns is hardly developed. The fur is thinner in summer than in winter, but not as pronounced as in the northern polecat forms.

The durability coefficient for the Perwitzky fur is estimated to be 30 to 40 percent. When classifying fur animals into the "fineness classes" silky, fine, medium-fine, coarse and hard, the Perwitzky hair is classified as medium-fine.

trade

In the past, fur had a certain value for Eastern peoples, as it was often given by rulers as a gift or award for deserving subjects. In an older description it says: "Because it is neither big nor warm, his fur is not respected." Internationally, many skins were never traded. At the beginning of the 20th century, German furriers dyed their skins in such a way that they resembled the European polecat, or they were dyed from the hair side using a brushing or tapping process so that they resembled the pine marten , "which they had in terms of market value several times tenfold ”. In the 1920s and 1930s, skins played a certain role for a short time as a set of women's clothing and for light, attractive fur linings .

Around 1988 the annual delivery was estimated at no more than 5,000 skins.

Fur finishing and processing

For general refinement, see the main article → Pelzveredlung

Regarding the status of the fur refinement of polecat hides in 1985, a refiner writes that the Americans, who consumed a large part of the goods, mastered the process quite well, which was also due to the fact that the skins there were mainly processed in natural colors. Critical specialist buyers checked, among other things, the leather pull, the thick neck area, especially in the fur of male animals. Less good skins with a yellowish undercoat received the best possible degree of whiteness through a “fining”. The hair, especially the guard hair, was allowed to be attacked as little as possible. If the hair was too yellow, or the product was of even poorer quality, the pelts were colored. Especially with shades of brown you got a nice combination between the colored undercoat and the dark awn.

At first, polecat skins were mainly used for inner lining, mostly with tails on or in between. From around 1900 to around the 1940s, animal- shaped scarves, so-called fur necklaces, were popular alongside other small fur items (muffs, scarves, headgear and other items) . In addition to other species of marten , polecat skins were also used for this. Single-skin necklaces made from marten-like were, quite common in the trade, called "stranglers". The increased use for large-scale manufacture started late. In 1948 a polecat coat was considered “en vogue” (“in fashion”). Finally, the skins of the European and steppe iltissas, natural or dyed, were processed into jackets, coats, inner linings, blankets and trimmings and small parts.

The skin processing places special demands on the furrier . One working technique of skinning is omitting , lengthening the skins at the expense of the width by means of V- or A-shaped cuts (in the case of difficult polecat skin it may be labor-intensive to expand it to a W-cut, in 1930 a specialist book even suggested the double W-cut). This creates narrow stripes along the length of the garment. Complicated strip guides can also be implemented with this. The waistline of a coat is additionally emphasized by the stripes, which are also waisted. A specialist book wrote in the middle of the 20th century: “In recent times, fashion has also helped this item to gain reputation and recognition as a coat in the striped processing. It is really difficult to process polecat omitted. Only those furriers who already have a lot of venture experience and who have mastered the subject should start such work. The perfection, with which some polecat coats have been worked in Germany in recent years, naturally gives the experts among the furriers the incentive to try it themselves. "

The difficulties in processing lie on the one hand in the lively coloring, but above all in the strongly varying hair lengths within a coat. This problem hardly arises when the skins are assembled with full heads and not left out. In the case of a coat, this results in an effective and lively image, but certainly undesirable for a restrained wearer. This liveliness is often softened by dyeing in which the natural colors can still be recognized. If left out, the garment has a more even appearance, but with the above-mentioned problems for the furrier. Leaving out the pelts to the length of the coat, especially in the case of the smaller skins of female animals, results in unattractive narrow stripes, and the outlet seams also mark “extremely ugly” because of the differences in color and hair length. Therefore, with small skins, or for very long pieces, two skins have to be cut into one beforehand - with the difficulties mentioned. Under certain circumstances, beautiful effects can be achieved by working the skins crosswise or in a haircut upwards, so that the light undercoat dominates even more. However, not every model is suitable for so-called “overturned” processing.

In 1965, the fur consumption for a fur board that is sufficient for a polecat coat was given as 70 to 80 pelts (so-called coat “body”). A board with a length of 112 centimeters and an average width of 150 centimeters and an additional sleeve section was used as the basis. This corresponds roughly to a fur material for a slightly exhibited coat of clothing size 46 from 2014. The maximum and minimum fur numbers can result from the different sizes of the sexes of the animals, the age groups and their origin. Depending on the type of fur, the three factors have different effects.

As with most types of fur, each part of the skin is used by the polecat if there is enough attack. Mainly from the pieces of fur that fell off during the processing of the fur, inner lining is made. The main place for the recycling of the fur residues in Europe is Kastoria in Greece as well as the smaller town Siatista, which is located nearby . Polecat tails, like other marten tails, were used for stocking purposes. With the addition of brocade fabric , capes and pelerines were made from it in the past .

Polecat-colored refinements of other types of fur

The following were dyed as polecat imitations: rabbit fur , opossum fur (“polecat goat ”), lambskin , goat skin (“polecat goat ”) and arctic hare fur (“polecat hare ”).

facts and figures

- 1801 in Krünitz's Economic Encyclopedia : “… Marder and Iltiß are almost one and the same animal, at least as far as the fur is concerned. The marten is only rarer, and its fur is therefore more expensive. [...] but they can be dyed to sables. "

- 1838 in Schiebes Universal-Lexikon der Handelswissenschaft : “The Poles like to wear tiger skins. The sack (that is, as much bellows sewn together as one needs to make a fur) is paid for with 25-30 silver rubles. "

- In 1911 Brass mentioned that the skins of the American black-footed turtle were not on the market, as was the species Putorius larvatus or P. tibetanus that occur in Tibet and the Himalayas . The latter is “light-colored, almost yellow-white, with a blackish appendix on the shoulders and trunk, the undercoat is white, but very dense and woolly, the upper hair is long, a lot of hair between the toes. He lives like the European polecat and smells like that. "

- In 1911 the value of a Perwitzky fur was 3 to 4 marks, before that 1.50 marks (in 1925 already 14 to 18 marks). Between 3,000 and 4,000 pieces were sold annually, "earlier came a lot more".

- 1918–1939 : For this period between the two world wars, the German furrier newspaper gives around 100,000 pieces of captured polecats as the annual spread.

- In 1923/1924 , 865,645 polecat hides were tanned in Russia, which corresponded to a value of 1,488,493 rubles. In 1924/1925 it was 854,096 skins worth 1,303,331 rubles. Of these, the “Far East” accounted for 1488 pelts worth only 1200 rubles.

- In 1925 , Brass stated the value for European polecat skins at an average of 8 marks each, the value of Russian polecat skins, which were used exclusively for inner lining, at around 5 to 6 marks each ( 2 marks in 1911 ). Every year around 200,000 European skins were traded and 50,000 Russian skins were exported.

- In 1925 , the tobacco wholesaler Jonni Wende offered: “Polecat: German 10 to 28 Reichsmarks; Russian 11 to 30 Reichsmarks; Virginian ("spruce marten") 180 to 850 Reichsmarks (depending on size and quality). "

- Around 1928/1929, polecat skins were listed on the Leipzig tobacco market per piece:

- German great 17.50 to 22.50 marks

- Russian fine white 14 to 20 marks

- Russian excellent black 18 to 25 marks

- (for comparison: beech marten prima = 60, - to 85, - marks; pine marten great 60, - to 75, - marks)

- In 1936, there were almost 1,000 European polecats in North American farms, according to official information.

-

Before 1944 , the maximum price for polecat skins was:

- natural or colored: large RM 26; medium 18, - RM; small 14, - RM, low 6, - RM. For a feeding table 250, - RM.

- In 1950 the Soviet Union supplied 129,000 polecat hides. In 1960 there were 95,000 skins.

- In February 1980 the Scottish company Argyll Mink Farms brought about 2,600 highland Fitch skins on the market.

- In 1985 , 320,000 polecat hides (breeding) were offered in Helsinki . Five years earlier, in the 1979/80 season , there were only 30,000. The total attack was estimated to be over half a million. At that time, a new breed called "Starlet Mist" came on the market, which still accounted for well under 10 percent of the total supply, but achieved twice the price.

- In 1986 , Dathe / Schöps stated in retrospect that the occurrence of tiger tiger skins for the entire distribution area seemed to be less than 5000. Fewer than 1000 skins were reported for the Soviet Union and around 1200 for Bulgaria ( 1966 ).

- In 1986 the Russian tobacco products trading company Sojuzpushnina offered 8000 polecat skins , the next year 6700.

See also

annotation

- ↑ a b The specified values ( coefficients ) are the result of comparative tests by furriers and tobacco shops with regard to the degree of apparent wear and tear. The figures are not unambiguous, since the subjective observations of the durability in practice are also influenced by tanning and fur finishing , as well as numerous other factors in each individual case . More precise information could only be determined on a scientific basis. The division was made in steps of 10 percent each. The most durable types of fur according to practical experience were set to 100 percent.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel ’s Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10. revised and supplemented new edition, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, pp. 40–44.

- ↑ a b c d e f Heinrich Dathe , Paul Schöps, with the collaboration of 11 specialists: Fur Animal Atlas . VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1986, pp. 167-170.

- ↑ a b Harry Mc. Laggan: Strong demand for highland martens . In: Pelz International , 1980 issue 7, Rhenania-Verlag Koblenz, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ a b c d Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, published by the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1911, pp. 487–491.

- ↑ a b Paul Schöps; H. Brauckhoff, Stuttgart; K. Häse, Leipzig, Richard König , Frankfurt / Main; W. Straube-Daiber, Stuttgart: The durability coefficients of fur skins in Das Pelzgewerbe , Volume XV, New Series, 1964, No. 2, Hermelin Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin, Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig, Vienna, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ a b Paul Schöps, Kurt Häse: The fineness of the hair - the fineness classes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. VI / New Series, 1955 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ a b c d e Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XVIII. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1949. Keywords “Iltis”, “Iltishase”.

- ^ Prof. D. Johann Heinrich Moritz Poppe: Johann Christian Schedels new and complete goods lexicon. First part A to L, fourth completely improved edition , Verlag Carl Ludwig Brede, Offenbach am Mayn 1814. p. 492 (keyword “Iltis”).

- ↑ a b Heinrich Hanicke: Handbook for furriers . Published by Alexander Duncker, Leipzig 1895, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Online query of the Europ. Polecat in the Red List of Endangered Animals in Germany and its federal states. science4you, accessed February 4, 2010 .

- ↑ Red List of Threatened Animal Species in Austria as of June 30, 1998. Austrian Species Protection Information System OASIS, accessed on January 13, 2010 .

- ^ Red list of endangered animal species in Switzerland. Federal Office for the Environment FOEN, accessed on January 13, 2010 .

- ↑ Appendix III of the Bern Convention. Council of Europe, accessed 13 January 2010 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Fritz Schmidt : The book of the fur animals and fur . FC Mayer Verlag, Munich 1970, pp. 246-256.

- ↑ Richard König : An interesting lecture (report on the trade in Chinese, Mongolian, Manchurian and Japanese tobacco products). In: Die Pelzwirtschaft No. 47, 1952, p. 52.

- ^ Herder's Conversations Lexicon. Freiburg im Breisgau 1854, Volume 1, p. 721., Permalink .

- ^ H. Werner: The furrier art . Publishing house Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, Leipzig 1914, pp. 95-96.

- ↑ a b Dieter Hack: Iltis - also up-to-date in the processing . In: Die Pelzwirtschaft No. 2, Berlin, March 6, 1985, pp. 33-34.

- ^ Friedrich Lorenz: Rauchwarenkunde , 4th edition. Volk und Wissen publishing house, Berlin 1958, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ a b c Hermann Deutsch: The modern skinning. Manual for the furrier, dyer, bleacher, cutter and garment maker . A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna and Leipzig, 1930. pp. 80–81.

- ↑ a b Author collective: Der Kürschner. Technical and textbook for the furrier trade. 2nd revised edition. Published by the vocational training committee of the Central Association of the Furrier Handicraft, JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 1956, pp. 185–203.

- ↑ Paul Schöps among others: The material requirement for fur clothing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Vol. XVI / New Series 1965 No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 7-12. Note: The following measurements for a coat body were taken as a basis: Body = height 112 cm, width below 160 cm, width above 140 cm, sleeves = 60 × 140 cm.

- ↑ Without indication of the author: Furrier's fur lore in the late 18th century . From the chapter "Kürschner" in the "Krünitz". In: "Das Pelzgewerbe", Vol. XVIII / New Series 1967 No. 3, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., P. 73.

- ↑ August Schiebe: Universal Lexicon of Commercial Science Volume HP, Leipzig and Zwickau 1938, keyword “Iltis or Eltis fur”.

- ^ A b Emil Brass: From the realm of fur . 2nd improved edition, publisher of the "Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung", Berlin 1925, pp. 584-585, 587-588.

- ↑ Jonni Wende company brochure, Rauchwaren en wholesale, Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Leipzig, New York, August 1925, p. 5.

- ^ Kurt Nestler: Tobacco and fur trade . Max Jänecke Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1929, p. 105.

- ^ Friedrich Malm, August Dietzsch: The art of the furrier. Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1951, p. 39.