Fur lining

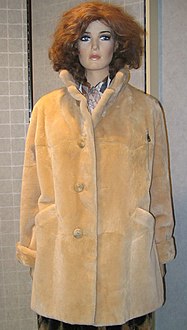

As fur lining or fur lining , the lining of textile or leather products with fur is referred to, in the main, this winter coats and jackets are. The fur remains hidden as a lining, as a trimming on the edge, but it can be shown as an additional collar or cuffs.

In addition to the peasant and shepherd's coats made of lambskin or goatskin , inner linings, together with the trimmings (fur collar and trimmings), were almost exclusively used from the early Middle Ages to the advent of modern fur fashion. There was also a short-term change in fashion with a changing preference for certain types of fur when, in the 19th century, fur began to be worn as a fur coat or jacket with the hair facing outwards.

- For the lining of furs with fabric lining, see → Fur silk .

General

Fur linings can be permanently incorporated, can be unbuttoned with buttons or snaps or can be torn out with a zipper or Velcro so that the fabric part can also be worn in warmer weather. At the same time, this enables fur and fabric to be cleaned separately . Often a fur collar that can be removed together with the lining or separately is part of it. Since the fur lining is often more durable than the surrounding textile, the cover can be replaced if necessary, modernized according to the wearer's new demands on the type of fabric and color. In the case of a garment lined with fur up to the front edges, where the fur borders the edges, a fur lining that is firmly attached to the fabric usually looks more perfect. In 1958, a practitioner of fur interior processing remarked with resignation about the removable fur lining: "Unfortunately, however, we have to say that the most perfect solution has not yet been found and it gives some headache to make this processing as beautiful as it is practical".

A variant of fur-lined clothing is reversible fur, on one side a material that can also be worn outside, and on the other side fur. Quite occasionally, reversible jackets or coats are also produced as fashion highlights, which instead of fabric have a mostly contrasting second type of fur on the opposite side. In February 1770, the Duchess of Chartres appeared at the Paris Opera Ball in a cloak with a two-meter train, inside and outside made of sable. The actress Romy Schneider (1938–1982) had a coat, one side made of cognac-colored Lakoda-Seal , the other made of wild mink .

Fur linings are either made from whole fur, such as muskrat , nutria , lamb , horse or hamster , or they consist of pieces of fur , the "waste" of fur processing, such as paws, heads, sides or other pieces of fur. Even the smallest of fur residues can still be used, mostly for fur lining. The center of European fur processing is located in and around the Greek city of Kastoria and the nearby, smaller town of Siatista .

In the past, the following were particularly designated:

- The Kürsen or courses , in Middle High German the name for a fur skirt. Also Kursit (mhd. Kursît, Kursat) was common and described both the fur overcoat also worn over the armor tunic if he was lined with fur as.

- The pelisse , in the late Middle Ages a fur-trimmed or additionally fur-lined overgarment worn by men and women. From the middle of the 18th century, a wide, cape-like coat or cape made of satin or velvet, about knee-length and with arm slits. The dolman of the hussar uniform, the short, fur-trimmed cape, is also called pelisse in France. In Austria-Hungary this throw was called Mente , in Germany it was simply called Pelz .

- The Gehpelz , even city fur , an elegant gentleman winter coat with fur trim and fur lining .

- The winter mozetta , a shoulder collar that reaches to the elbows and is worn over the choir shirt, usually for senior clergy of the Catholic Church, usually lined with ermine fur .

Otherwise the usual costume designations such as skirt, dress, coat etc. were used and added to a more detailed description whether they were lined with fur or trimmed. In the case of coats and jackets, only the torso is lined with fur, either set back to the inside of the fabric, or as trimmings up to the front edge while the collar is occupied at the same time, the sleeves usually only have a heat-retaining intermediate lining. Sleeveless capes, hats, gloves, muffs, shoes, foot bags and sleeping bags can also be lined with fur, whereby the fur is almost always visible.

Fur linings can also be made loose so that they can be worn under different items of clothing. This was particularly the case with the lining for soldiers produced during the two world wars. In the civil sector, hamster feeds were preferred, also loosely, without unnecessary width, which became known as "hamster shirts".

The manufacture of the fabric jackets and coats required for fur coats was subject to tailors until around the middle of the 19th century. Until after the Middle Ages, furriers were forbidden from making the winter envelopes themselves , in the fur industry still called envelopes , just as the tailors were forbidden to work or even just use fur lining incorporated, violations were relentlessly pursued. In the guild regulations of the furriers in Deggendorf it is stated in 1459: “Item so we also want that the tailor should not put the furrier's trade under any garment or disguise it. But whoever would convict this and thus invent and understand it, the same tailor should change our gentlemen's rate and pay it off with ½ pound Regensburg pfennig, without giving any grace. ”- There were disputes not only between furriers and tailors. In 1857 it was expressly stipulated in Braunschweig that the furriers, in addition to the shoemakers, are entitled to make and sell fur-lined overshoots.

Most of the men's clothing was equipped with fur linings. Feeding was considered a particularly difficult, responsible activity. In a report by a furrier about the already very differentiated division of labor in US fur production, it was astonished to say in 1902: "Even men's furs are mostly fed by female workers".

The son of the Italian tailor Balzani remembered how an “elite paletot” was created in the mid-1930s:

“During the war, the father Giovanni was an army companion of Dominico Caraceni, one of the greatest representatives of Italian men's tailors. A friendship developed that was never broken, not even when both became owners of the most renowned furrier and tailoring in Rome. So Caraceni sent the wrapped model for the fur lining to Balzini and then he personally accompanied the customer to the studio to try it on. And with both of them, together with a furrier and a tailor, the third and last act of the excellent production took place: the final rehearsal, the attachment of the fur lining to the already finished coat. "

If you follow Christoph Weigel's work “Illustration of the Commonly Useful Main Stands”, then it was the furriers in Rome during the time of Emperor Nero (37–68) who were the first to feed “clothes with peltwork”. In any case, the need there to adorn oneself with fur, inspired by Germanic and Gallic costumes, increased so much over the next two centuries that Emperor Flavius Honorius (384–423) prompted not only to wear reddish Germanic hair but also to wear fur to ban within the city of Rome.

Fur lining in courtly, urban and fashionable clothing

The development of fur clothing can be summarized as follows: "In the Middle Ages the furrier fed, in the Rococo he occupied and today the furrier is dressed", but the feeding of textile clothing with fur has always been an essential part, even if it is seldom visible in pictures of skinning.

That feeding, next to the dressing (tanning) of the skins was once probably almost the only task of the furrier, can be adapted to the old, and in some countries even today professional name surviving recognize. The German colored feeder mainly fed the noble types of fur, such as Feh (colored work) and ermine. Today's French “Fourreur” and the English name “Furrier” for the fur processor also mean “feeder”. A fur was a piece of clothing lined with fur or worn with the leather side of the fur facing outwards, not, as in today's parlance, a part with the hair facing outwards.

For the Middle Ages, there was a gradation in the type of fur-lined clothing according to social class. The rural population and the high Nordic peoples who feed on the hunt did not wear their fur lined with fabric, but either with the leather side facing outwards, or in extremely cold areas the fur underclothing with the hair inside and an outer fur over it. The European and parts of the Asian urban population had fur-lined, fur-trimmed or fur-lined and fur-trimmed cloth coats at the same time. The higher the class and the wealthier the owner, the more elaborate the fabric and, above all, the more expensive the fur. For their proclamation, emperors and kings preferred to wear robes lined and trimmed with hermelin, and fur robes were also part of the equipment of the upper nobility. In terms of luxury and splendor of clothing, the church dignitaries were in no way inferior to the feudal lords, they were among the main buyers of furs, "the finest fur with sable, marten, ermine, otter and beaver skins was just good enough for them."

Clothing as a status symbol never again played such an important role as it did in the Middle Ages; clothing showed rank, wealth, authority and power. Much more money was spent on it than in later times, when more and more other ways of emphasizing self-expression emerged. The ranking was also established through various dress codes, especially for the use of the individual types of fur. Today's robes can almost all be traced back to the Middle Ages. The fur used as class clothing has been preserved in various places, next to the coronation coats, especially on the robes of the clergy, mayors, judges and dignitaries of the universities. The need to warm these clothes, which are mostly worn in closed and now heated rooms, hardly exists today. Except in isolated cases among the clergy, fur is probably only used here as trimmings or trimmings and no longer for feeding.

Middle Ages, Gothic (around 6th to 15th centuries)

The first fur-lined clothing in northern Europe was owned primarily by the urban population; in the countryside, the predominant type of skin was native fur animals, mainly unlined sheep , and also goatskin coats and jackets, reversible, either with the fur or the leather facing outwards (so-called " naked fur. " ").

Until the 9th century, the end of the Carolingian era , fur clothing was one of the most distinguished gifts that Germanic emissaries presented to foreign princes and dignitaries. At least the most distinguished women wore at least a fur-trimmed coat. In descriptions, the precious fur border is always emphasized. Whether the item of clothing was lined with fur is often uncertain, possibly because ordinary lambskin was often used as the inner lining. The Norwegian King Harald Hafagre (* approx. 852; † 933) and Erik Edmundson († 883) of Sweden sent their courtiers to Nizhny Novgorod , the centuries-old trading center for Russian fur skins, to buy valuable fur to feed the coats.

A typical item of clothing for women at the beginning of the 12th century was the “corset”, a loose and wrinkled overhang that “created a rich and effective image with its folds and the piquant play of fur colors”. He was fed with Zieselfell as stained work or Fehfell as gray work , processed together as a stained gray. In a similar fashion, the men wore a round-cut coat or a short wrap, also adorned with fur, which "resulted in a game that is just as attractive as the clothing of the women". The hats were trimmed with fur, fur collars and fur gloves were also worn.

From the beginning of the 12th century, the individual classes began to separate themselves more from each other in their costumes, which was also reflected in the style of clothing. The clothing of the upper classes also became more and more ostentatious, at the same time women became the focus of society. The knight dressed in an almost feminine manner. All means were expended to appear elegant and splendid. Both tailoring and furrier art were in full bloom. A preferred type of fur of the noble classes, especially around the 13th and 14th centuries, was the feh , the fur of the Russian squirrel, which was used for almost all fur-lined items of clothing. The gray back fur is still used today for trimmings, the white peritoneum, the colored work , with its characteristic sides that remain from the back fur, for fur lining. Feh is almost always only mentioned in connection with magnificent and rich fabrics, the back fur or gray work even at the same time as the other, particularly precious fur, the white winter fur of the ermine . Up until the late Middle Ages, both types of fur were only allowed for high ranks, in Italy for example not only the nobility but also high magistrates, judges, doctors and their wives. In Germany, too, in the 14th and 15th centuries, the members of the municipal magistrate were equated with the nobles in clothing. Were estimated for embellishment and lining also marten furs , beaver pelts and lynx furs . The most valuable is the sable fur , which according to the dress codes was reserved for the very highest classes.

In the 15th century, European fashion became darker, stiffer, and more formal, and preferences for fur also changed. In the first place, instead of feh, were the furs from the marten family, above all the sable fur and the noble marten fur as well as black lambskin ("budge") from southwest Europe (according to Veale, but maybe this refers to the Turkmen Persian skins ?). Black budge for the lining of a black damask housecoat cost the considerable sum of £ 42 in 1543/44.

- In the previous century, 670 marten belly skins were used for a coat of John II of France (1319–1364). One of his sons ordered 10,000 skins to be used to line five coats and five women's jackets.

- A coat lined with fine white-tipped sables that Henry I (1068–1135) received, later King of England, cost £ 100 at the time. For comparison: for the time about 300 years later, a normal sable-lined coat was calculated to cost 13 pounds (2 pence for a fur price of 2 shillings).

- Between the years 1413 and 1418, Heinrich V (1387–1422) acquired 20,000 marten skins, two sable linings and 113 marten linings, obviously not just for his own use. When Heinrich died, he left 26 coats, all but six of which were lined with fur, plus 16 fur linings and 55 other furs.

- In 1433, an English knight's wife owned three coats lined with marten, one of which was lined with 360 marten skins.

- However, the types of fur lining represented at the English court were considerably richer. Black and white coats were lined with ermine, yellow velvet with leopard skin, rust-brown velvet with black rabbit and black damask, or crimson fabric with black lamb or marten. Less common types of fur such as lynx , mink , genette and fox were “the highlights of the season”, in throws made of black damask , velvet and crimson, gold-interwoven fabrics.

Konrad von Würzburg (* between 1220 and 1230; † 1287) described a creative fur processing in which the precious white stoat and black-brown sable for an inner lining were put together like a chessboard. Food made from fox skins , deer skins , rabbit skins and sheepskins was of less quality .

Often there was an ungirded wrap with a head hole between the coat and the tunic to keep warm. The lady of the novelist Ulrich von Liechtenstein (* around 1200 to 1275) was such a Suckenie from scarlet lined with ermine.

Renaissance (14th to 15th centuries)

The overcoat of the fur lining changed according to the clothing fashion. In the 13th century it was mainly a long, sleeveless cord coat, in the 14th century it was slowly replaced by a cloakroom coat that was open at the sides and had a wide robe collar made of the same fur as the lining. In the Middle Ages and the following centuries, the trimmed and fur-lined garments predominated, pure fur clothing is relatively rare, it is hardly to be found in the fashionable image. Above all, it was a sleeveless coat that was trimmed and lined with fur, from around the 12th century a fur lining is sometimes visible. In the 13th century, the fabric was mostly monochrome, the earlier decorations such as embroidery, pearls and gemstones are missing when the coat is lined or trimmed. From the early 14th century you can find a fashionable modification on illustrations, the Gugel , a collar hood in which the fur lining comes into its own (e.g. in the Codex Manesse ).

At no time was fur missing from clerical garb. Medieval ordinances stipulated that, for example, the lower clergy, like the peasants, were only allowed to use sheepskins (pellicae). In addition to the fur coat, the clergy sometimes also used their fur-lined hood , a sleeveless coat with attached headgear, in winter . In the case of religious nuns, it is particularly the cap (Latin cappa), a long, sleeveless coat lined with fur. Like the male costume, the lay sisters of the English Order of St. Gilbert wore a coat lined with white sheepskin, which, unlike the canons' coat, was not white but black. According to the rules of the order, this included a black consecration lined with white sheepskin (a hooded head veil). Ermine was also frequently used as fodder, not only by clergy women of higher rank, as with many canons with coats of usually sluggish length, but above all by French nuns. The Carmelite Sisters there wore a white cloth coat lined with ermine at festivals. But simple rabbit fur was also used as coat feed. The wide, black cloak of the noble nuns in the Estrun Abbey near Arras is completely lined with white rabbit skins.

In the second half of the 14th century, fashion narrowed considerably and fur lost its importance. In the male costume, the coats were mainly lined with fur. Towards the end of the 14th century, the fashion for loose, richly clothed garments returned. The man wore the tappert , an outer garment of both a coat-like and skirt-like character, which was again richly lined with fur and trimmed, which contributed greatly to the decorative effect of the part, which was otherwise often valuable. Particularly elegant trimmed tappers were the hallmarks of the French-Dutch costume, which set the tone for Europe as Burgundian fashion. In the French-Dutch version, the wide sleeves are particularly noticeable. The courtly French-Dutch costume included a woman's dress that hardly differed from the male, known as Houppelande . The fur lining came into its own in the wide-opening sleeves that hung down to the ground. Similar dresses can be found in Italian women's clothing, in which, as in men's clothing, the sleeves, lined with fur, already opened at the shoulders.

Baroque, Rococo, Empire, Biedermeier (late 15th century to mid 19th century)

In the second half of the 15th century, fashion became narrower again. This time, however, the interest in fur remained, it was only used a little more sparingly. That changed again when in the last two decades the Schaube replaced the Tappert as a male, bourgeois piece of clothing, but it now also appears in women's clothing. However, the Schaube did not develop properly until the first half of the following 16th century. Now the fur was no longer just a narrow trim, but merged into a wide, sweeping shoulder collar, and the fur peeped out from the sleeve slits. Or the front parts were cut in such a way that the magnificent inner lining lay wide across the coat. A simple skirt with fur lining and a bordered fur trim on the neckline and the front slit can also often be seen under the mostly colorful scabbard. Dürer, Holbein the Younger and all the important portrait painters preferred to portray their clients in a fur-lined showcase that signaled their prosperity. Hardly ever again was fur "so decorative and dignified" as it was with this piece of clothing at that time.

The price of a fur-lined screw fluctuated. Michael Beheim noted in his household book in 1590 "for a black chamois mederein or hasz socks with a mederein ladtz for 28 guilders in". In 1518 Lukas Reim gave his brother Dr. Gilg bought a marten hood for 75 fl., While Anton Tucher paid 35 fl. In 1507 for an already worn black scabbard with a marten fur lining. Attempts were made to keep the acquisition costs lower by making the part of the lining that is not visible when worn from a significantly cheaper material than the trimmings and trimmings. In the Zimmerische Chronik (1540/1558 to 1566) it is said that the marten and sable screws were mostly only lined with sheepskin. At the English court, the servants' coats were fed with the cheap gray rabbit fur, Henry VIII (1491–1547) had a fur lining of the rarer types in his rusty brown coat, black rabbit fur was about twelve times more expensive than gray.

In the second half of the 16th century, the scabbard was shortened to become a resin cap or a short Spanish cloak with fur trimmed or at least fur trimmed around the shoulders . In the costumes of some German cities, for example in Stettin or Silesia, the coat lost its short, fashionable cut and became the half-length, fashionable shoulder coat of the bourgeoisie, while it continued to hold its own in more traditional places, such as the German imperial cities. In some places you can even find real fur coats with the hair facing outwards.

Towards the end of the 16th century, with the beginning of the Baroque era and its lush display of splendor, the leading role of the male costume in the development of fashion slowly ended. A separate women's fashion was created, which has ultimately dominated all fashion since the 18th century. The fur trimmings on men's clothing also became less, in contrast to women's cloakrooms, which were increasingly trimmed with fur in the 18th century. On the whole, fur hardly influenced the fashion image, with the exception of the muff, which came into fashion around 1600. Louis Gordon, a French doctor, wrote at the turn of the 17th century, surprised by a custom that now seemed strange to him: “I have heard of elderly women from good families who lived during this period, they saw people who were in theirs floor-length coats almost choked with their trains. And in addition, whether winter or summer, it was a matter of honor to wear them lined with ermine or martens ”.

From the last decades of the 18th century the Redingote enjoyed fashionable popularity as a men's coat . It could be lined with fur and trimmed. Frequently was a fur trimming and a warm fur lining the dressing gown or housecoat , which was allowed to also like to portray, sometimes supplemented by a fur or fur-trimmed house cap. It was either three-quarters long or usually came down to the feet as a dressing gown . Among the invoices still preserved from Electress Anna Maria Luisa de 'Medici there is an instruction from December 1717 to her Düsseldorf court curator Franz David Geillmeyer for 20 Rtl. 30 Sbr. for "feeding a night skirt with 2 Muscovite lynx skins (10 pieces), 36 pieces of gray Wercks skins (9 pieces) and macher's wages (1 piece, 30 pieces) for the sleeves".

In Vienna, the Greek merchants stood out with their long fur-lined caftan-like coats until the 18th century. In the second half of the 18th century, the diverse capes , cloaks and sheaths of various kinds were lined with fur or trimmed, after in the first half of that century people were often content with a lined manteau or a quilted jacket that was popular at the time .

Since the 17th century, the variety of types of fur used for fashionable clothing had increased considerably, especially due to the fur trade with North America . The first mention of Russian Astrakhan as lining (a light, curly lambskin, here it means the curly Persian ) was in 1764, when an Earl of March referred to "My black silk coat, lined with Astrakhan".

Johann Georg Krünitz named the following types of fur around 1775:

- Sable , mainly for decorating hats

- Marten and polecat for man's muffs, for hats and clothing

- Ermine for fur lining for women of the class, also for sashes, mugs, hats and trimmings

- Lambskins , which were sometimes used as an ermine substitute

- Rabbits , which were very popular with women’s fur fur, also liked to make ermine

- Hamster , the fodder which is typical for the later felling, was mentioned

- Gray work, the Fehrücken were used for man furs

- Mink for female fur rashes and for hats

- Genetten cats , also for rashes, occasionally also for lining

- Otter , marble and seal skins, however, only for cap trimmings, only otters also for male mugs

- Fox skins , wolf skins and bear skins were a good inner lining of Mann's dresses, as well as lynx - cat - rabbit skins and the skins of the hazelnuts or ground squirrels and white winter weasel

- Tiger , panther and wolverine skins were made into sleeves

- Domestic sheepskins and sheepskins were seen as good linings for gloves and hats, and foreign lambskins were also used

Krünitz did not mention chinchilla fur , which only became known in Europe in the 18th century , but he did point out that the list of fur types he cited was by no means complete.

One of the most famous furs of the 18th century was the Voltaire sable cape . When Voltaire returned to Paris in 1778 at the age of 84 after 30 years of exile, he was welcomed by the Académie française with a ceremony on March 10 and elected President. His appearance was described as follows: “His powdered gray wig was the type that was in fashion forty years ago. Then a square cap, while over his coat and trousers he wore a red coat lined with hermelin, and over this this Catherine-the-Great- sable cape ”.

Refined fashion ends with the Biedermeier period , life as well as fashion becomes simpler, less demanding and bourgeois cozy. The fur-lined men's coat is tight-fitting or takes the form of the "Blüchermantels", a travel coat with a multi-layered shoulder collar. Until then, fur in men's fashion was more of a decorative accessory, but as a fur skirt it seemed "initially sensational".

The painter Jacob van Schuppen (1670–1751) in a dressing gown lined with pieces of fur and a fur hat

Johann Joachim Winckelmann , House gown with wolf food (1768)

Founding period (from the middle of the 19th century) to the First World War

While fur lining was still a necessity in practical winter clothing in the 17th century, this changed in the time of the industrial revolution, a time of general fashion change. For fur, this meant, among other things, that the apartments were warmer thanks to different construction methods, new window glass and windows and better stoves, and the fur-lined dressing gown was hardly needed any more. However, women's fashions became more fitted, and clothing fabrics became thinner and finer, and warmer outerwear became a necessity.

All in all, the 19th century was very fuzzy, but a little reserved in men's clothing. The most important fur-lined item of clothing since the last decades of the 18th century has been the coat, generally known as a redingote , a long body skirt, fitted with inserted lapels and lapels. The fur lining continued as a collar and cuffs, if the fur was not just a trimmed edge. The Havelock , a coat with a half-length tippet, which appeared in the 1830s , was also worn in winter with fur lining, fur collar and fur cuffs on the sleeves. In its time, it represented the pinnacle of elegance and gradually became the winter clothing of men, especially those of set age. The otherwise very reserved English men's coat fashion set the trend in its time and remained decisive for future times. When women’s fur with the hair on the outside began to establish itself in women’s fashion around 1900 and men in the new, open-top automobiles wore shaggy fur, the Burberry company explained to its customers in its catalog published in the first years of the 20th century: “English men do not take well the continental monstrosities in the form of horse skin, sheepskin, wolf skin, and other variations that have hair, wool, and fur on the outside. The more distinguished way is to simply use the fur as lining ”.

Johann Heinrich Zedler's Grosses Universal-Lexicon from 1741 describes the “fur” for women in a very limited way as “actually a short petticoat lined with delicate fur and smokers, so worn right over the shirt, does not have too many folds, and generally with a colorful one light catone is coated. A lined Contush with Polish armchairs and a collar, an overhanging fur or Polonoise , a Hungarian fur with a smooth body, and trimmed with Ungrian bows from the front belong there. "

The furs of the urban population of Russia did not differ in cut from the rural population , but they had a cover made of cloth, whereby the more carefully worked out fur lining was usually visible as trimmings. While the German furriers did not have a high opinion of the abilities of their Russian colleagues - apart from the exemplary imperial cabinet skinning in St. Petersburg - they recognized their achievements in the field of fur lining production as good and correct work. The Russian fur processors cut the pelts into several pieces, which were then used in the factory to produce particularly even food boards from backs, dewlaps, paws and heads from “tobacco products made available in large quantities”. The more influential and wealthy the fur wearer, the finer the cloth and the more noble the fur with which the men's fur was lined or trimmed. The Russian soldier's skirt was also lined with fur in the 18th century. While traditional clothing was still worn in Russia in the 1880s, where fur lining was a normal commodity, a change was already taking place under similar climatic necessities in Poland, where "there was also a lot of luxury in the same". While the lower classes stuck to the traditional form of their clothes lined with sheep, fox or wolf fur, “the higher and richer classes, as well as those who claim to belong to them, wanted only those lined with more noble fur and wearing studded robes, the shape of which corresponded to the fashion emanating from Paris ”.

In 1842, modern women's fur fashion began in London with a seal jacket, in which the hair was worn outwards. It became popular after Queen Alexandra wore a black seal jacket when she arrived in London to marry the Prince of Wales (1863). The innovation came in a time that was open to this, when fur was used on all female clothing, on collars, capes, trimmings and the trimmings consisting of muff, scarf and hat. Even fur-lined or edged over dresses, coats, jackets and capes, there were of various kinds. The essential forms were the Redingoten , Douilletten , Envelopen and similarly named overcoats, often dress and coat were simultaneously. Warming lining or trimmings were "very welcome, because they are an essential addition to the chemise dresses made of very thin fabrics from the turn of the century". The great extent and importance of fur in the fashion of the time were shown at the London industrial exhibition , the Great Exhibition , in 1851 . The Hudson's Bay Company demonstrated the variety of furs coming from America . Red foxes and cross foxes were mainly exported to Russia and China for lining and trimmings. Mink fur is mentioned for the first time as "mainly liked by women". Lynx skins were also used for food, other types of fur were needed in various European areas for regional costumes. Another exhibitor recommends raccoon, but also lynx, mink and gray fox for lining the Schuba coats , a Hungarian traditional jacket, "exclusively for men, in Russia and all of Germany".

Less conspicuous was the men's faux fur, which has dominated winter men's fashion more and more since the second half of the 19th century and has been preserved in its type, without the name faux fur, until today. Depending on the general fashion, it was longer or shorter, the fabric colors were mostly restrained. When doing winter sports, the gentleman probably wore a fur-lined jacket with a fur collar and cuffs, and fur-lined gloves were also in use. Until the first half of the 19th century, sleeveless coats remained popular, with the fur trim mostly continuing below the fur collar in the edges of the coat. From 1810 to the 1860s, the fashion magazines depicted it as a characteristic item of clothing in any length, completely edged with fur and a small fur collar.

During this time the fur sewing machine was invented , which made processing much cheaper. This also had an effect on the fur lining, which was often laboriously sewn together from small furs. Lively patterned hamster, Susliki - and Burundukfelle or monochrome mole skins were light lining materials. From fur waste particularly inexpensive food to work, in the Greek fur Closer city Kastoria inside but often sewed and its surroundings as well as in northern China until well into the 20th century, still with his hand, both districts from which the pre-assembled for further processing today fur lining come .

For sledding in appropriate areas, there was some time particularly warm lined, long coats, as well as the so-called coachman fur or driver's fur . This was often designed as a livery for the servant, in two rows with metal buttons and cuffs made of fur. For drivers who are particularly exposed to the cold, it was usually lined with thick sheepskins, and the collar was often studded with raccoons or beavers. The landowners in eastern Germany in particular had fur-lined coats made of sturdy fabric for sleigh and carriage rides, and back linings, muskrats, cheap mink and martens, nutrias and light lambskins were widely used. Especially in Wroclaw there were special companies that manufactured the majority of these furs. The feet and legs of the passengers were kept warm by high, fur-lined footmuffs that were above knee height, mainly lined with sheepskin, in the better versions with Australian opossum , wallaby or wolf skin. The outside was made of leather, velvet or grosgrain fabric. The travel blankets were also often lined with fur, depending on their ability with sheepskins, country foxes, wolves, lynxes or skunks .

Since the first motor vehicles were still unheated and open, the driver, who was still rare at the time, now also needed an item of clothing that was particularly warm, the motorist's coat . Under the name, however, a fur to be worn with the hair facing outwards was understood, mostly long-haired with a rather martial appearance. The women's car coats, on the other hand, were made of fabric, fur-lined and trimmed. The Deutsche Reichsbahn also placed large orders for its drivers because the passenger trains were not yet heated.

The price list "Winter 1913/1914" of the large and traditional fur trading company Heinrich Lomer on the Leipziger Brühl gives an indication of the fur worn before the outbreak of the First World War . At the same time, the list gives an impression of the variety and gradation of the different coat qualities.

In technical terms, the color term "blue" means a particularly dark, usually somewhat bluish winter coat. The opposite designation is "red", for the less appreciated lighter summer skins. "Smoke" skins are particularly thick-haired. “Rinds” are low-quality, not fully grown or in summer pelts. He offered the furriers on prefabricated fur feed boards:

- Fehrücken lining , in 14 quality, type and price levels, from 30 (lower) to 225 marks (extra dark blue)

- Fehkopf food, from 30 (natural, lighter and reddish) to 130 marks (natural, extra dark and dark)

- Fehwammen lining ( Weissenfelser Arbeit), from 8 (red and lower) to 55 marks (extra dark blue fine)

- Muskrat back lining , from 45 (lower) to 135 marks (extra dark great smoke)

- Muskrat lining, from 35 to 45 marks

- Brown or black muskrat lining, from 28 to 100 marks

- Dyed and electrically depilated strips of Sealbisamfell (length 100 cm, width 35 cm), from 25 to 45 marks; Seal muslin sponges 20 to 35 marks

- Civet cat food , from 135 (lower) to 270 marks (best smoke fine)

- Hamster food , bars (good) 15 to 21 marks; Rotunda 8 (minor) to 13 Mark (good)

- Landiltis fodder , from 175 (lower) to 475 marks (good smoke dark)

- Kolinsky food , from 100 (flatter, large or small good) to 175 marks (natural fine smoke large); Sable-like colored from 80 to 125 marks

- Mink lining , from 125 (rind lining ) to 1700 marks (extra dark, very fine)

- Nutria feed , 110 (lesser) to 260 marks (fine smoke); Sealnutria feed 150 to 200 marks

- Australian opossum back food , 125 (lighter or reddish) to 260 marks (dark fine blue)

- Australian possum side food, 15 to 28 marks (various grades)

- Dyed astrakhan linings , from 30 (lower) to 250 marks (finely patterned)

- Sable side lining , from 100 to 450 marks

- Sable-claw fodder, from 150 to 450 marks

- Sable throats lining, from 70 to 160 marks.

Władysław Daniłowski, coat with Halbpersianer (1863)

Birdskin Lining Cape (ca.1882, Metropolitan Museum of Art )

Corduroy men's Ulster with lambskin lining and wombat collar (1910)

Jennie Churchill with Tibetan lamb lining (before 1914)

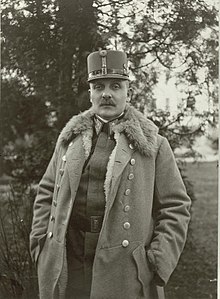

Kaiser Wilhelm II with nutriage-lined cape (1914)

Fur lining production and sales using the example of Frankenberg in Saxony, 1895

While outer fur began to dominate fur fashion at the turn of the 20th century, in 1895 the author of a detailed description of skinning in the Saxon town of Frankenberg , then around 12,000 inhabitants, understood fur-lined garment under fur as a matter of course: “Furs apart from the skin, require a cover into which the lining and the trimmings are attached. "

The furriers' calculation for a man's fur looked something like this (a little more was usually earned on women's fur):

| 14 to 15 sheepskins for the feed at 1.50 marks | 22.50 marks |

| 2 large or 4 small sheepskins for the sleeves | 5.00 marks |

| 7 muskrats for collars, flaps and cuffs at 2.50 marks | 17.50 marks |

| 2 ¾ meters of cloth for the cover of 7 marks | 19.25 marks |

| Tailor's fee for making the cover | 7.00 marks |

| = Direct cost, without furrier wages and without imputed and other ancillary costs | 71.25 marks |

|---|

The fur was sold for 90 marks at best.

The working time that the furrier needed to produce was two days.

However, in Frankenberg with its five furriers at the time, the orders for fur lining had declined dramatically in the past thirty years, "the furrier workshop was deserted". While the fur-lined coat was a necessity for many citizens up until then, passenger transport by mail cars and wagons had been almost completely replaced by the railroad, which was better protected when traveling. The railway connection to Chemnitz , which was completed in 1869, also enabled the Frankenbergers to shop in a much larger city with better-equipped fur shops, and local customers were even sought out from Leipzig and Dresden. The churches and other public facilities had meanwhile been provided with heating systems. The previously mostly heavy and medium and thus larger and cheaper sheepskin qualities were therefore no longer in demand. Light lambskins were only used for a small part of women's and men's furs, while women's coats were also lined with feignons, saddlebacks, muskrats and hamsters. Another loss of income was that the furriers no longer made this small-skin lining from individual skins, with the exception of the seldom requested muskrat lining, but from prefabricated food boards that were mainly sewn together by women in poorly paid manual labor in factories or at home. Since the earnings from the furrier were not enough, the Frankenberg furriers were always, as in other places of comparable size, at the same time cap makers and operated the purchase and sale of native raw hides . They also tanned (tanned) most of the native skins themselves.

The desolation of skinning was also related to a change in fashion that had taken place in the fur trimmings, the coverings and also in the small furs, the so-called haberdashery goods. Men's furs were traditionally trimmed with fur around the neck, over the chest and around the front edge of the sleeves, they had collars, pocket flaps and lapels made of fur. With women's furs, the trim ran around the entire top and front edge, as well as around the ends of the sleeves. In the 1860s and 1870s, almost no winter coat was made without a trim. With women's jackets it was usually narrow, with half-length and long coats it was sometimes almost the width of the length of a muskrat. Since the end of the 1980s, a small part of the men's fur was worked as a "fur skirt" without any trimmings. The half-length and long women's fur extended towards the end of the 1870s and the beginning of the 1880s to become the “waist and bike coat ”. In the case of the latter, the stocking disappeared immediately, in the case of the former gradually. In 1895 only a few waistcoats were occupied, the jackets, however, had retained the trim. The demand for the "tumbling overcoats" had risen not insignificantly, but that for the jackets had fallen extraordinarily. Less than the fourth part of the jackets was produced at the time, "a development which the furrier never tires of complaining and which has robbed him of an abundance of work and earnings". With the tailored coats, ready-made clothing came onto the market for the first time, initially only covered with fur, usually with Russian, cheap, not very durable but "eye-catching" black rabbit fur , later also lined, preferably with cheap boots. Because of the low price, these finished goods were bought well, not in Frankental itself, where there were no clothing stores, but in Chemnitz.

While the trimmings were less in demand, the variety of fur types used for them increased. In the 1860s muskrat, beaver, bokhara [Bukhara ?, according to today's understanding identical to Russian Persian], astrakhan, Persian (“three fine sheepskin sorts”) and Virginian otter were used , in the 1870s mink fur and polecat fur were added . At that time, women's coats were mostly lined with rabbit fur , the better and half-length jackets with muskrat. While Kanin disappeared with the decline in jacket production in favor of natural-colored and dyed muskrat, mink and polecat were also added to women's fur in the 1870s, later skunks and the black-dyed, velvety-sheared "sealbisam". Together with Sealbisam, the rabbit fur also returned as a black-dyed, sheared "Sealkanin". Due to the variety of fur types, the furriers could only buy smaller amounts of fur at less favorable conditions. The furrier had previously supplied the lambskin lining for the fur boots. However, felt boots had become so fashionable that they were no longer in demand.

The fashion of the cover had also changed in terms of shape and type of fabric. Until well into the 1870s, women's and men's coats were not made to the waist, they were "sack furs". The men's fur covers, which have always been made by tailors, got “a little cut”, the women's waistcoat completely replicated the body shape, the “wheel” partially replicated. As the pattern became more complicated, the manufacture of women's sleeves also shifted to the ladies' tailor. The furriers were left with the production of the jacket covers that were going out of fashion, even the jacket covers that were just becoming topical at the time, he could not make himself. Since the bag-like furs of one size fit more customers than the new, body-hugging shapes, the furriers could hardly prefabricate finished sleeves or furs in the summer months because of the higher sales risk.

The cover for men used to consist of dark green, later dark blue cloth. This had no effect on the furrier, who continued to source the fabric in whole or half bales from the factories. In the beginning mostly black cloth, later partly velvet and "an extraordinary amount of plush" were used for the women's fur. In the mid-1880s, ready-made fabrics became fashionable for women, especially for furs that were worked to the waist. The variety and the sudden change of fabric patterns made it too risky for the furriers to keep these fabrics in stock. This led to the emergence of a middleman who kept these materials in stock - which inevitably led to a further reduction in earnings for the furrier.

However, the previously rare repair work, which until then had often been carried out by the tailors, had increased. A particularly large number of furs had also been bought in the 1860s to 1870s. During this time, the furriers were busy in summer and winter, sometimes with the help of the wife and another helper, two in winter, working into the night. The services included replacing old fur covers with new ones, redesigning them in line with the latest fashions, repairing damage caused by moth damage, and more. In addition to caring for the fur parts that were kept in storage over the summer , this work was the main occupation of the furriers during the warm season. Now the furriers could do the work almost alone, even in winter. The constant increase in "patchwork" could "not remotely" replace the losses.

The manual work, which once represented the almost exclusive turnover of the Franconian furriers, had degenerated into a sideline in 1895. Because of the competition from the factories, hats and caps were rarely made in their own workshops. The earnings from the headgear were by no means better, the furrier bought a children's hat for 25 pfennigs and then sold it on for 30 pfennigs. Whereby hats were often left lying around with the rapid change in fashion. Despite all the hardships, the existence of the profession of furrier in Frankenberg was seen as safe.

Between two world wars, World War II

In the 1920s, the first leather jackets and coats were also lined with fur, at that time mainly for use as driver's fur . A decade later, men's fashion became more elegant and fur largely disappeared inward, instead of flashy pelts the short-haired varieties were used. In the 1930s, sales of fur linings had also decreased significantly, and fur-lined women's coats had been almost completely replaced by fur coats. Skinning and tailoring were mixed up at the time, there was a lot of staff and dressing up again. Maggy Rouff even lined travel coats with leopard fur, but the fur remained clearly visible in the large musketeer cuffs that contrasted with a very small collar.

Russia, 1921: Fyodor Iwanowitsch Chalyapin with beaver skin,

on the right a lambskin-lined dust coatKing Ferdinand of Romania in a fur-lined cape and his wife Queen Maria (1922)

Coat with astrakhan lining (France, 1922)

Beach suit and " summer fur " (Italy, "Parisian model", 1930)

After the Second World War

In February 1947 Christian Dior New Look created an elegant clothing line for women that disappeared during the war. At about the same time began "the age of mink fur", only in Germany for a few decades more ousted by the southwest African Persian fur ( Swakara ). The fur fashion shifted completely to the outer fur, fur linings were for a time only rarely made. In the 1950s, Dior showed off a mink-lined raincoat.

Erica Pappritz , the controversial chaperone of the late German post-war period, issued a special recommendation in 1956: “In principle, however, we should refrain from wearing a coat that has no fur lining with a fur collar. On the other hand, it is by no means a mistake if you do not see the fur lining of a well-made city coat and thus its character from the outside, because the wearer has given up a collar ”.

Around the mid-1990s, Karl Lagerfeld merged two materials that were even more different in value, sable and a denim that was already a bit worn. The short jackets were quickly copied in mink or with the cheaper, less provocative rabbit fur, some were lined with fur, but mostly only covered with fur. In the 1960s, fur fashion spread around the world and also embraced the younger generations. Cheaper fur and rising incomes made it affordable for almost everyone, especially in prosperous Germany. In Vienna, Austria, fashion, and with it fur fashion, was consistently a little more opulent than in apparently more sober Germany.

A German market study in 1978 showed that 20 percent of the 506 men surveyed owned an item of clothing with fur (including lambskin), 17 percent of those surveyed had a jacket or coat with the fur inside.

Since around the end of the 1980s, fur has increasingly lost its importance in fashion. A series of unusually warm winters, accompanied by anti-fur campaigns, gradually spoiled the Central European population for buying fur. The existing pelts were preferably converted into inner linings. In accordance with global warming, fur linings have become lighter, velvet weasels and velvet mink, Fehwamme, muskrat, nutria and the lighter types of fur pieces have since been preferred materials for inner fur. Since the beginning of the 21st century, there has been more and more trimmings again, especially on hoods, mainly with fox and raccoon.

Today, almost exclusively light materials are used as outer fabrics for coats, such as microfibre - cotton and silk fabrics, and wool fabrics for jackets and vests. To a much lesser extent, leather clothing is also lined with fur.

Coat with mink lining by Farah Pahlavi (1957)

Women's velvet feh costume , men's coat with velvet mink lining (2006)

Men's jacket, camouflage-dyed, sheared red fox , turned (2020)

Fur lining in local costume and in non-industrialized cultures

The European rural population almost exclusively used regionally available fur types for their fur clothing. As a rule, she wore lambskins, which, especially in Hungary, Romania and other eastern countries, were often decorated on the outside with braids, braids and very ornate embroidery. The peasants' jackets, which they wore to work at home and did not take off under their coats, like the festive jackets, were lined with fur. The women also wore a fur-lined outer garment, which was often more richly trimmed than that of the men and often also had fur lapels and pockets. Swedish, Russian or Polish farmers, on the other hand, usually preferred sheepskin without a fabric cover, with the leather side facing out. In most of the European folk costumes, women wore a variety of short bodice jackets that were lined and trimmed with fur in winter. Their fashionable form emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the course of the 19th century the differences between traditional costumes and fashionable clothing shifted in favor of fashion, especially in the cities, with peasant fur still in use. In the not quite eastern areas, such as Poland, the fur-lined, half-length or long cloth coat predominated among the rural population. In the rest of Central and Western Europe, too, there were characteristic landscape differences in cut and color, as well as in the decorative ingredients, the cuffs, borders, and braids.

Until the 18th century the official dress of civil objects was the Schaube , significantly, also Ehrrock named after the talar-like robes of officials had disappeared in the fashion they were long gone. It was usually lined with brown fur. The Saxon police order of 1612 stipulated that only “ locksmiths , mayors and those to be reckoned with” were allowed to use tree and stone marten, but that the other councilors should be satisfied with wolf and fox except for stocking their caps. The Saxon dress code of 1750 already allows the mayors and councilors as well as "graduates and professors of the university" to black foxes, sables and the like.

The 1st Wuerttemberg Police Order of 1549 demands under threat of punishment: “The peasants in the country shouldn't let anyone else wear bad fur from lambs, goats and the like and let it be disguised. Common citizens (that is, the townspeople), artisans and shopkeepers in towns are not allowed to wear disguised clothes, not even martens or the like, delicious food, but rather allow themselves to be contented with rough fur lining, as are their wives and children. If, however, a craftsman is elected in court and council in a city and used for other honorable offices, he may wear fox and the like for simpler furs, their wives fennel . ”Depending on their rank, officials were permitted to wear more valuable types of fur. Only aristocrats were allowed to wear even more expensive clothing and fur.

In the far north, fur linings have always been one of the foundations of people who have penetrated there, in order to be able to survive at temperatures well below freezing, often for months. Loose fur clothing, if necessary with the hair inwards and with a second layer with the hair outwards, ensured that body heat was retained. The parkas of the Inuit are particularly beautifully decorated , with the peculiarity of the Amauti with its flared back, which merges into a hood in which the Eskimo woman carries her toddler with her.

Chukchi (1913)

Fur lining in the ruler's regalia

- For the production and adaptation of a prince's coat to the following generations, see as an example the → King's coat of William I of the Netherlands , from 1815 to today.

Even attitudes of class, office and dignity emerged from fashion attire and then solidified or typified into fixed forms in which they only participate in a limited fashion change. In accordance with your supra-individual character, symbolizing office, status or dignity, the nature, composition and layout have been precisely defined over time. This also applied to the fur that was used in each case.

The most elaborate of the fur-lined garments is the princely coat, in which the ruler appears on the day of his enthronement and in which he can also be depicted for posterity. It is made of purple velvet or silk and is lined and trimmed with ermine, the symbol of immaculate purity. The princely coat emerged from the commonly used medieval coat forms and has developed over time into the huge pompous coat that can only be worn on festive occasions, the train of which has to be worn by several people. From the second half of the 12th millennium, fashion preferred fur linings and trimmings, and ermine gradually became the fur of princely people. The ermine collar that appeared in the 14th century and which reached to the shoulders on the long coat, buttoned on the right shoulder, remained characteristic of the princely coat after it had disappeared from fashion in the 15th century. In other respects, too, the princely coat remained largely unaffected by the change in fashion. The development was not regionally limited, but was roughly the same in all European ruling houses. Differences can be found in the increase in the solemn and representative, for example in German princely coats. At the coronation act and on other representative occasions, the wife of the ruling ruler wore a princely lady's mantle, usually without the large ermine collar. There are also many examples of fur linings and trimmings, preferably made from ermine, in the costumes of the knightly orders. The Knights of St. Georg in Nivelles Abbey in Brabant, Belgium, wore "a long, ermine-lined, black velvet coat" over their white dress, which was trimmed with gray work on the lower hem .

The regalia of the Doges of Venice and Genoa, which bore a certain resemblance to the garb of the highest ecclesiastical dignitaries, were similarly elaborate. As with the clerical Mozetta, a distinction was made here between a summer and a winter costume. Often their regalia were not only lined with ermine, but were particularly conspicuously trimmed with the long-haired lynx dewlap, the white, mostly black-speckled belly of the lynx skin .

The mozetta is a shoulder collar that reaches to the elbow and is worn over the choir shirt, usually for higher clergymen of the Catholic Church. The papal Easter and winter mozetta are also covered with ermine. The red velvet winter mozetta, lined with ermine and trimmed, was last used by Pope Benedict XVI. , Bourgeois Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, seen, also the hermelin-lined Camauro cap .

Fur lining in military uniform and in war clothing

With the advent of firearms, soldier armor lost its importance and instead “the soldier struts along in clothing that has become more martial”. It was not until around the time of the Thirty Years' War that officers probably wore the overcoat with trimmings, known as the Hongroline , the name indicates the Hungarian origin of the garment with the characteristic trimmings. The hussar regiments set up in the European armies based on the Hungarian model adopted this Hungarian costume. This was especially true for the dolman , later the fur hung over the longer husarka or attila , a short sleeve jacket with rich lacing and trimmings. The fur color was mainly white or gray, or it had the black color of the Persian, usually tinted in addition.

The officers in particular were free at any time to have their coats lined with fur, as long as the winter outfit of the branches of service did not already have fur-lined coats. In Russia, senior officers wore valuable coats trimmed with sable fur. Instead of fur lining, fur vests were also worn under outer clothing, especially in the Luftwaffe.

In times of war, fur lining became a necessity even for ordinary soldiers, without its representative function, which it had together with the trimmings in the upper ranks. A full fur suit was even suggested for pilots, a jumpsuit to be worn under clothing. In England there was the Sidcot suit , named after the pilot Sidney Cotton , which came into civilian use in 1917 and, with some modifications, enjoyed some popularity for twenty years. The Sidcot is a three-layer suit made of waterproof silk with an inner lining, collar and cuffs made of fur, the outer shell made of Burberry . Like the civilian travel bags with fur lining, there were field bags for the soldiers.

During World War II American furriers worked in the campaign "fur vests project" loose to wear fur lining for the GIs . During the Second World War, Joseph Goebbels , Reich Propaganda Leader and Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, announced for the first time the “collection of wool, fur and winter things for the front”. The population was called upon to make appropriate donations in kind. Jews were expressly threatened with death if their furs were not delivered. The collected furs were also turned into lining by furriers and fur seamstresses ,

French infantry arquebusier (18th century)

Carl of Prussia with sable lining (1852)

Indian cavalryman (1857)

Pilot in a fur-lined flight jacket and trousers

(USA, 1921)

Cleaning bins for US fur military clothing

(World War I)In Recklinghausen, furriers work on furs worn during the Second World War to make fur for the soldiers on the Eastern Front

Hermann Göring , Sable Trim and Fur Lining (1942)

Preferred types of fur

Presumably every type of fur that is sold to the fur trade has also been used as inner lining. However, certain preferred types of fur can be identified. Depending on the degree of cold in the landscape, more or less warming, i.e. usually long or short-haired varieties, are fed. If the outer fabric or the leather coat to be fed is strong and heavy, the fur lining should usually be particularly light. For the Central European climate, lighter types of fur, i.e. the skins of smaller fur animals, are preferred anyway. Inexpensive types of fur are naturally more frequently used than expensive ones, especially food from the remains of the fur processing are a very good alternative that is grateful in terms of durability.

All of the types of fur that are mainly used for feeding are prefabricated as semi-finished fur products by handicraft businesses, which are mostly located in certain centers . The tablets are also sold under the name fur lining in tobacco wholesalers.

A lot of inner linings are made from worn furs by the furrier on behalf of customers. If the fur of a fur is rubbed through age and wearing and is otherwise not as attractive as the new fur, it is usually still very suitable as a lining material. By incorporating it into fashionable poplin, microfibre or silk coats, inner fur is made from “noble” types of fur that the owner would otherwise not have bought for price reasons.

mink

Apart from sheepskin and lambskin , mink fur is currently the most widely used material in fur clothing. It is at the top of the shelf life and is available in many natural colors and can also be dyed in any fashionable color. Almost one hundred percent of it comes from breeding and is available in quantities regulated by the market. It is used as a lining for very high-quality, mostly elegant coats. Much more common are foods made from the cheaper mink paws, mink nourkulemi (rear part of the belly) and mink thiliki (chest part behind the front paws, particularly light).

sable

Sable fur linings are the epitome of luxury. The English fur expert George C. Cripps described it in 1913 as the perfect material for a fur lining, "it is light, warm and elegant". However, his additional statement applies that if a pure color was not so important, it would not be very expensive either, thanks to improved fur finishing methods, it no longer applies.

As with mink, feedings from the waste from coat, jacket or trimming processing are much more common. The trade names are the same as for mink fur. When combined with trimmings or trimmings made of sable fur, the result is the same look as a piece of fabric lined and trimmed with sable, at a much lower price.

Ermine and weasel

Ermine, with its pure white winter fur still also the fur of kings, no longer has the meaning in fur fashion that it had for centuries until the beginning of the 20th century. For feeding purposes, the not completely white, more or less reddish colored, seasonal transitional skins are preferred. Above all, the skins that do not produce an attractive pattern when put together are usually colored in very dark colors, such as dark brown, especially black, because of the color balance. Smaller quantities of reddish-brown summer fur are produced, which are also used for fur lining.

The weasel pelts, which are similar to the summer hermelin except for the missing tail tip and the smaller coat size, come from Asia today. Usually the upper hair is plucked out and the fur colored, which is how they are refined as "velvet weasels" in stores.

Rabbit

The rabbit fur has long been a symbol of cheap fur. Taken from nature, it is also abundant thanks to its massive increase, its almost worldwide occurrence and the re-enactment, because it is mostly perceived as a troublemaker. Unfortunately, the fur of the wild rabbit has the disadvantage that it has a tendency to hair when worn, which is particularly uncomfortable with an inner lining. In doing so, they brought the skins of domestic rabbits into disrepute, which, especially when shorn, have good wearing properties and make for a very warm and grateful lining. In addition, house rabbits are bred in many very attractive colors and can be colored to any color. The fur of the Rex rabbits in particular makes a particularly attractive trim material. After the private rabbit breeding in Europe has declined with increasing prosperity, a beautiful rabbit fur has the price of a low-priced mink fur.

Muskrat

Muskrat, especially the lighter peritoneum, the muskrat, is an ideal material for feeding purposes. The fur of the dyke and bank pests has an excellent durability and is caused by the state-ordered hunting of the muskrat anyway. Most of the time, however, it is not put to use, in the Netherlands the considerable accumulation there is probably largely completely destroyed by official order. Sheared, mostly also colored, the fur is sold as "velvet bisam".

hamster

Hamster fur is the classic lining material for a man's coat. It is particularly light, it is considered the most vividly drawn fur animal in Europe, the high-quality fur lining is sufficiently conspicuous and still looks quite conservative. In most countries, however, the hamster is now under species protection. Formerly heavily persecuted as an agricultural pest, modern agriculture has now almost completely stolen its habitat. The center of German hamster fur processing was in the Harz region until the GDR era .

Feh

Fehfell , formerly the fur of upscale classes, results in an even more conspicuous lining fur than that of the hamster. While the back fur of the Russian squirrel is reservedly gray and fully in the hair, its ventral side is flat and white. When dividing the fur, a piece of the dark fur side is always left on the dewlap used for fodder purposes, which results in a very characteristic pattern that has also found its way into the design of the coat of arms as the " heraldic feh " in its various compositions.

For simultaneous trimming and trimming, it is advisable to use the back fur.

Burunduki, Susliki, Viscacha

Burunduki skins, Susliki skins and Viscacha skins, all skins of very small animals, come from the hunting of agricultural troublemakers; hunting for fur purposes would not be financially worthwhile. With a correspondingly high general income of the population resident in the areas of origin, the hunted animals, which are regarded as pests, are not used. Because of their low weight and flat hair, these skins are particularly suitable as lining in areas with milder climates. The price of fur was also often subsidized by hunting premiums, which in Germany and other countries also applied to hamsters, for example.

Fur scraps

The fur residues that fall off during fur processing represent a major part of the fur lining. Almost every part of the skin is prefabricated as semi-finished fur products for further processing by specialized furrier companies or in home work into fur bodies, fur panels or fur linings .

Mainly:

- Front and rear paws (called "claws" from sheep and goat skins, for example " Persian claw", but these are seldom used for inner lining), often also under terms such as "mink claw" and "sable claw"

- different side parts of the skins ("sides", "thiliki", "nourkulemi")

- End pieces ("heads" and "pumps")

- Tails , as far as hairy ("tails")

- Curly fur remnants and other fur remnants are put together to form piece bodies.

Due to the attack, most of the current pieces of fur linings come from the waste from mink fur processing.

processing

In the past, the furrier used to feed in very simply cut pieces of fabric to save time, without a previous, precisely fitting cut using a pattern. Starting from the back, he attached the fur with stop stitches to the fabric stitching to the side seam, as well as the front parts, beginning at the front edge. In the neck holes he adjusted the lining, also along the side seam and in the shoulders, where he pulled the fur edges against each other . It was even said that the furriers of the Balkans cut the lining with the pocket knife and starting in the back, without any side seams, the fur lining, still "in the presence of the suspicious customer", in whose coat there was more stitching than sewing.

However, the exact removal of the pattern from a customer's coat has always been considered a particularly difficult and carefully performed furrier job. Up until the 1970s, the budding German master furrier had to prove that he was not only able to remove the pattern to fit, but also mastered the art of fitting ("knocking on") an inner lining himself. Although at that time the furrier usually no longer sewed himself and the feeding of the finished fur lining was now mostly entirely the responsibility of the fur seamstress who worked for the furrier .

The tailor's area of responsibility was largely separate from that of the furrier. Either the customer came to the furrier with the finished coat to be filled and lined, or the tailor brought the unlined, custom-made work over to the completion with fur lining and fur collar, possibly with the pattern. Only the clothing industry offered fully lined furs for retail as early as 1900. It was not until around the 1970s that furriers themselves began to produce fabric coats and jackets for fur linings in large numbers.

If the sleeves are also lined with fur, care must be taken with smooth-haired fur, especially with stiff upper hair, that the hair does not twist or push up the sleeves when worn. Processing in the opposite direction can remedy this: alternately up and down the hair, or forwards and backwards.

- Removing a pattern for a fur lining

Lighter fur linings are usually connected to the cover by a simple warped seam . For thick-leather or long-haired or thick-haired pelts, an open-edged warped seam is used or needling is preferred, so that the otherwise formed seam beads do not press outwards onto the cover.

Fur lining, processing and fur consumption in 1930

The furrier Hermann Deutsch wrote in 1930:

"Since fur linings are usually purchased ready-made, I limit myself to listing the main types along with the number of fur and rows [number of rows of fur on top of each other]:

- Beaver lining , 2 lines, Grotzen forward, working against the hair [hair blowing upwards], about 9 to 10 skins.

- Beaver side lining , mostly 3 heights.

- Muskrat back lining , approx. 60 to 70 skins.

- Muskrat lining , from large dewlaps about 60 to 70, from smaller dewlaps about 130 pelts.

- Muskrat and pump food , assembled in the known manner.

- Backs , about 110 to 125 skins, both smooth and curved and recently also in tips, put together like a mosaic.

- Fehwamme , mostly only in panels of 80 to 90 furlets, whereby 2 panels are equal to a rotunda.

- Fox food , both natural and colored, 2 rows about 13 skins.

- Fox claw lining , always worked with the tip of the paw on the wide section, the individual longitudinal lines only made of left and right paws so that the hairstyle goes down.

- Hamster food, May hamsters 3 to 3 ½ rows, about 48 to 54 skins. Autumn hamsters are significantly lower in quality, the individual skins are also much smaller, usually 5 to 6 rows, around 70 to 80 skins.

- Polecat lining , 3 rows, 42 to 54 pelts.

- Genette , 3 lines, mostly 19 heads.

- Lammfellfutter to driving furs , skins 7 to 8.

- Schmaschen , about 25 skins.

- Marmot . The number of skins as well as the height of the skin depends on the type of skin.

- Mink lining , partly made from 2, but mostly from 3 heights, approx. 24 to 40 skins.

- Nutria feed , 3 to 5 rows, about 20 to 36 skins.

- Sable fodder is hardly available in stores today. In this context, however, I would like to mention the sable and marten throats, claws and side lining. "

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt: change of Pelzmoden in earlier centuries . In: Das Pelzgewerbe Nr. 3, Berlin et al. 1968, pp. 37-40.

- ↑ a b c Eva Laue: The interior finish . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , 1958, No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 264-271.

- ^ Francis Weiss: The debut of the fur coat . In: Marco - Information from the Fränkische Pelzindustrie Märkle & Co., Messen 1974 , p. 40.

- ^ A b Marie Louise Steinbauer, Rudolf Kinzel: Marie Louise Pelze . Steinbock Verlag, Hannover 1973, pp. 149, 193.

- ↑ a b c d e Eva Nienholdt: Fur in the costume of the early and high Middle Ages . In: The fur industry No. 3, Leipzig. et al. 1955, pp. 91-96.

- ↑ Eva Laue: The interior finishing . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , 1959, No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 34-35.

- ^ PN Sprengel's arts and crafts in tables . 2nd collection, 2nd edition, Verlag der Buchhandlung der Realschule, Berlin 1782, p. 456.

- ^ Karl Schädler: The guild regulations of the furriers in Deggendorf from June 7, 1459 . In: Die Pelzwirtschaft No. 8, Berlin August 8, 1962, pp. 24-25.

- ^ Collection of laws and ordinances for the ducal Braunschweigische Land . Volume 44, p. 55.

- ↑ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: The furrier craft . Part I, No. 3–4, chapter The furrier trade . Larisch and Schmid publishing house, Paris 1902, p. 85.

- ↑ Illustration of the common-useful main stands From which regents and their servants who were assigned in times of peace and war, bit all artists and craftsmen . Pp. 616-617.

- ↑ a b c d Reinhold Stephan, Bochum: On the history of the tobacco goods trade in antiquity and the Middle Ages and the development of the Russian-Asian region from 16.-18. Century . Inaugural dissertation at the University of Cologne 1940, pp. 14, 30–31, 66–67. Table of contents .

- ↑ a b c Paul Larisch : The furriers and their characters . Self-published, Berlin 1928, pp. 49, 70–71.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Elizabeth Ewing: Fur in Dress . BT Batsford Ltd, London 1981, pp. 23, 28, 30-31, 82, 84, 102, 120, 123-124, 135 (English).

- ↑ Eva Nienholdt: Fur in European clothes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 2, Leipzig et al. 1955, p. 70.

- ↑ Joh. E. Fischer: Siberian history from the discovery of Siberia to the conquest of this country by Russian weapons . St. Petersburg 1768 p. 319f. Secondary source Reinhold Stephan, p. 23.

- ↑ a b c C. Gahlen: The furrier in the style change of the time . In: Kürschnerzeitung , Leipzig October 1, 1933, pp. 604–609.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Elspeth M. Veale: The English Fur Trade in the Later Middle Ages . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1966, pp. 109, 134-136, 141, 144-147, 176 (English).

- ^ Francis Weiss: The Sheep Aristocracy. In: All about fur. Issue 9, Rhenania-Fachverlag, Koblenz, September 1978, pp. 74-77.

- ^ Dorothee Backhaus: Breviary of fur . Keysersche Verlagsbuchhandlung Heidelberg - Munich, 1958, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ a b Eva Nienholdt: Fur in the costume of the early and high Middle Ages . In: The fur industry No. 5, Leipzig. et al. 1955, pp. 163-169.

- ↑ a b c d e Eva Nienholdt: Furs on the ruler's robe , on secular and spiritual religious and official costumes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 3, Berlin et al. 1958, pp. 132-138.

- ↑ a b c Eva Nienholdt: fur in the fashion of the 16th century . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 1, Berlin, Leipzig 1956, pp. 17-25.

- ↑ a b c Eva Nienholdt: Fur in the fashion of the 18th century . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 6, Berlin, Leipzig 1956, pp. 235–245.

- ↑ Jürgen Rainer Wolf (Ed.): The cabinet accounts of the Electress Anna Maria Luisa of the Palatinate (1667-1734) . Klartext-Verlag, Essen 2015, p. 1141, ISBN 978-3-8375-1578-7 .

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: The history of the skinning . Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1967, p. 204.

- ↑ a b c d Eva Nienholdt: Fur in the fashion of the 19th century . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 2, Berlin, Leipzig 1957, pp. 81–90.

- ^ A b Andrew Bolton: The Lion's Share . In: Wild Fashion Untamed . The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2005, pp. 49, 63, 73, ISBN 1-58839-135-3 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); ISBN 0-300-10638-6 (Yale University Press) (English).

- ^ Johann Heinrich Zedler: Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 27, p. 220.

- ↑ a b Simon Greger: The art of furrier in all its activities at the level of present perfection . In: New scene of the arts and crafts , 130th volume, 4th edition. Bernhard Friedrich Voigt, Weimar 1883, pp. 199–200, 220 ( → title page ).

- ↑ a b c d Eva Nienholdt: Fur in folk and national costumes . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 1, Berlin et al. 1958, pp. 30–40.

- ↑ a b c Anna Municchi: The man in the fur coat . Zanfi Editori, Modena 1988, pp. 20, 38, 48-49, 51, 61-62, ISBN 88-85168-18-3 .

- ↑ a b Friedrich Jäkel: The Brühl from 1900 to World War II , 3rd continuation. In: Rund um den Pelz No. 2, February 1966, p. 82.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and Rough Goods, Volume XXI . Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1951, p. 131, keyword “rind” .

- ^ Price list Heinrich Lomer, Rauchwaren, Leipzig, Brühl 42, Winter 1913/1914 , pp. 11–29.

- ^ Albin König: The furrier in Frankenberg in Saxony . 1895, pp. 313-341. In: Writings of the Verein für Socialpolitik. LXIII. Investigations into the situation of the craft in Germany . Volume 2, Part 1, Kingdom of Saxony , published by Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1895.

- ^ Fritz Hempe: Handbook for furriers . Verlag Kürschner-Zeitung Alexander Duncker, Leipzig 1932, p. 166. → Table of contents .

- ↑ Anna Municchi: Ladies in Furs 1900–1940 . Zanfi Editori, Modena 1992, p. 122 (English) ISBN 88-85168-86-8

- ^ Author collective: Der Kürschner. Technical and textbook for the furrier trade. 2nd revised edition. Vocational training committee of the central association of the furrier trade (ed.), JP Bachem publishing house, Cologne 1956, p. 73. → Book cover and table of contents .

- ^ Karlheinz Graudenz, Erica Pappritz: New label . German Book Association, Berlin 1967, p. 176. Quoted from: Karlheinz Graudenz, Erica Pappritz: New label, Südwest-Verl., Munich 1956.

- ^ David G. Kaplan: World of Furs . Fairchield Publications. Inc., New York 1974, p. 21 (English).

- ↑ Primary source OA Haseloff: Pelz in Deutschland - a representative statistical study of motivation, behavior and the market . Berlin 1978. Quoted from: Matthias Zeidler: Analysis of the tobacco product market in the Federal Republic of Germany - market structure, market behavior and market results . Diploma thesis, 7th semester in Business Administration, March 1, 1982, Frankfurt am Main. Appendix 7.3.

- ^ Gotthilf Kleemann: The furrier trade in Göppingen . In: Alt-Württemberg No. 1, Heimatgeschichtliche Blätter der IWZ, 1968, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ a b Eva Nienholdt: Fur in the war costume and uniform . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 6, Berlin et al. 1958, pp. 271–276.

- ↑ George R. Cripps: About Furs . Daily Post Printers, Liverpool 1913, p. 99. (English) ( table of contents ).

- ^ "Eh.": Skinning and finishing in Southeast Europe . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 20, Berlin, May 15, 1936, p. 5.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and Rough Goods, Volume XVIII . Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1949, p. 55, keyword “food” .

- ^ Hermann Deutsch: The modern skinning. Manual for the furrier, dyer, bleacher, cutter and garment maker . A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna / Leipzig 1930. pp. 315-316.