Persian Claw

Persian claws, the fur paws of the Karakul sheep , are an important article in the fur industry, depending on the fashion. In the period after World War II , when Persians were the main item in fur fashion in the Federal Republic of Germany , coats and jackets made from Persian claw were not just a cheaper substitute for Persians. Furs made from Persian claws are lighter than those made from whole pelts. With the appropriate combination of the claws and the use of leftover fur (Persian pieces), you can create your own looks. Their material value is determined by the hair drawing and the correct section of the claws from the fur.

General

The term claw for fur leg parts is actually only the skins of Hufträger, including the Persian or Karakulfell . This is why the fur industry has repeatedly argued that all extremities from other types of fur should be referred to as paws. But as early as 1895, the processing of fox “steal” and sable “steal” was described; Even an Austrian fur lexicon from 1950 makes no difference, in addition to Persian or Karakul claws and foal claws , it also mentions fox claws as an example .

The fur of the Russian Persian is curly in its historical type, which is still bred to a lesser extent today. The claws, on the other hand, are more flamed and moiré. In contrast, the Swakara Persians from Namibia, which have been in greater demand in the western world since the Second World War (1939–1945), have a moiré pattern in their torso. For the most part, their claws have almost no markings, they were less in demand in the past and had little or almost no value.

Karakul sheep are mostly bred black, the skins are usually also colored black. In addition to artificial coloring, there are natural colors:

- as other main colors gray ("natural Persian") and sur (golden brown)

- brown in the three main shades: red and light brown, brown and dark brown

- halali (chalili), two-colored, these are brown karakul with black sides and pump .

- odd , uniform gray-blue-brownish skins

- sedinoi , dark and black-gray karakul with a narrow, gray back center line

- gulgas (guligas), brown and white hairs in various shades of color.

The Persian claws are almost always not processed directly into coats or jackets, but from semi-finished products , so-called Persian claw bodies, which are assembled into bars in advance .

Natural Swakara raw fur with claws

History, processing

Ancient statues from the Hittite period show kings with headgear, which, according to the way they are depicted, indicate Persians. Tobacco dealer Francis Weiss wrote that areas north of the Oxus ( Amu Darja ) have always been of great importance to the noble lambs. The first news about the production of Persian coats dates back to 1869, when the emir of Bukhara gave the Russian tsar three furs made of gray karakul skin as a gift. The image of a Persian coat is known for the first time from 1898, here referred to as a long jacket; a French magazine showed a broad-tailed model with a sable collar .

From Samara , a large gathering place for lambs, it is said that the legs of the lambs were already being processed there at the same time, so that the fur, traded as Persian claw in the German-speaking area, was already in fashion. The Russian traveler Peter Simon Pallas wrote in 1771: “Most of the fine lambskins that are sold in Russia undisputedly come from here; just like the paws of the lambs here from those Kalmyks women, to whom they are included in payment, first put together in straps and then in furs and sold cheaply. In order to get a cheap and sewing thread for themselves, these women pull the threads of Russian linen cut up by a yard and sew the common goods with it, since otherwise they take in front of them split animal tendons, which are much more durable. "

The idea of using the claws in modern Persian fur fashion is said to have originated in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century, until then, according to Jäkel, the Persian remains were unused.

In 1902 Paul Larisch described the processing of the much flatter and barely marked claws of the Persian broadtail skins , not to be confused with the later bred broadtail Persian (Swakara): The sloping heads and claws are combined into special panels. The claws usually diagonally in a zigzag shape . Karakul or Persian pieces represent a very special value. The furrier will rarely sell the rubbish, but rather put it together himself in the quiet time, since he will achieve a much higher profit with it than by selling the pieces, which are probably also very well paid for (1928). With the Persian, practically every part, no matter how small, is recycled, and the curl structure makes sorting relatively uncomplicated. For the Persian claw bodies, curly pieces are often processed in order to achieve an appealing striped effect, at the same time it makes the price of the more expensive claws cheaper. Occasionally, in times of low wages, the non-moiré tips of the claws were cut off and processed into bodies with a very low rating. The curly legs are knocked off and often come with the Persian piece bodies. The most popular bodies are usually those made from Persian claws, the heaviest ones are made from Persian head pieces.

In November 1932, the Leipzig fashion house Schüler offered Persian coats for 575 marks in an advertisement, Persian claw coats cost 340 marks.

After the Second World War, the Persian was considered a classic “German” fur until it was replaced by the mink in the 1970s. The fur scraps that accumulated in the German and Austrian workshops were still processed in-house in the summer months when there was little work, in particular the relatively large Persian claws, which therefore require less working time. Persian claw coats made up a significant share of sales not only in department stores but also in fur retailers. In Germany, Austria and other countries, there was a separate house industry with the production of Persian claw boards or directly finished Persian claw coats and jackets. However, with the economic miracle, the German workshops were very quickly used to capacity and the wage level elsewhere was soon so high that it was usually more economical to export all the pieces from the furriers to Greece.

In the Greek regional district of Kastoria , especially in the city of Kastoria , the furriers began to specialize in the assembly of the remains of the skin processing as early as the first half of the 18th century, later also in the smaller town of Siatista, which is not far away . Even today, a large part of the so-called pieces of fur , including the Persian claws, go to Kastoria, where they are put together to make plates, panels and bodies. From there they are exported for further processing, although in the last few decades the Castorian furriers have abandoned the mere piece processing and many companies also produce finished fur on a large scale (see fur leftovers # Kastoria and Siatista ). Fur leftovers are now largely exported to Asia, especially to China, to countries with an even lower wage level than in Greece. In China, fur processing, including the production of pieces of fur boards, also has a very long tradition.

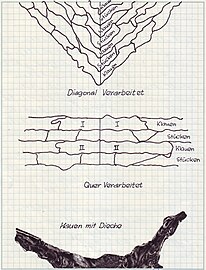

Shortly before 1955, serial production of Persian claw bodies began in the GDR after trade contracts for the delivery of fine fur skins had been concluded with the Soviet Union in 1951 . The ready-made parts manufactured by VEB Pelzbekleidung Delitzsch differed from the panels manufactured in Greece, for example. In the GDR, the claws were sorted into right and left as well as different, also different black, color finishes. The claws were then moistened and stretched out the next day, the ideal size should be 3 by 15 centimeters. As with the fur sorting, a preliminary and a fine range were created. About two to four kilograms of claws were needed for a body. In the pre-range, a distinction was made between smooth and moiré hoofs, but above all in seven hair length differences (smoking differences), extremely flat claws were not suitable for processing. During the fine sorting, the claws were placed one behind the other on cardboard for the seamstress and sorted. The flat side was placed against a recorded line. Up to a strip width of seven to eight centimeters, the claws on the smokier, more curly side were supplemented with fur remnants. It is the side on which the thief was previously , also called nakedness, an almost bald spot between the leg part and the body skin. The claws were edged with the skinning knife and the pieces adjusted. After sewing a ribbon about 36 meters long was created. These stripes enabled individual adaptation to the respective pattern, lengthways, crossways, parquet and diagonal processing were possible. Such work was awarded a gold medal in 1981 at the International Fur Congress in Liptovský Mikuláš , Hungary.

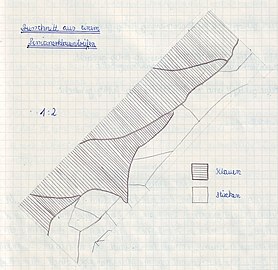

- Persian claw processing. From the workshop weekly book of a furrier apprentice, 1960 (sketches).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and Rauhwarenkunde, Volume XX . Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950, p. , Keyword “Persian Claws” .

- ↑ Heinrich Hanicke: Handbook for furrier Heinrich Hanicke. Instructions for the efficient operation of skinning . 1895, plate 65.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and Rough Goods, Volume XIX . Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950, p. , Keyword “stealing” .

- ^ Francis Weiss: The Sheep Aristocracy. In: All about fur. Issue 9, Rhenania-Fachverlag, Koblenz, September 1978, pp. 74-77.

- ↑ Wolf-Eberhard Mourning: Karakulschafzucht. Association of allotment gardeners, settlers and small animal breeders, Berlin Central Association, specialization: noble fur breeders (publisher), 1967, p. 9.

- ↑ Peter Simon Pallas: Journey through the various provinces of the Russian Empire . Imperial Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg 1771-1776, first volume, page 150. Reprinted by the Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, 1967.

- ↑ Friedrich Jäkel: Der Brühl from 1900 to World War II, 3rd cont. In: "Around the Pelz" No. 3, March 1966, Rhenania-Verlag, Koblenz, p. 200

- ↑ Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: The furrier craft . Part II, self-published in Paris, approx. 1902/1903, p. 58.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma jun .: The furrier's practice . Published by Julius Springer, Vienna 1928, pp. 234–237.

- ^ In: General Jüdisches Familienblatt , No. 45, Leipzig November 25, 1932, p. 1.

- ↑ Editor: Mink clothing - the hit for over ten years. In: Pelz International. Issue 4, Rhenania-Fachverlag, Koblenz, April 1984, p. 34.

- ^ Johannes Fiedler: Development and variants of piece production. Processing of karakul claws and pieces . Lecture on the occasion of the XIII. Fur Congress 1988 in Sofia, Bulgaria. In: Brühl No. 6, November / December 1988, VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, pp. 10-11.