Tail turning

In the fur industry, with a few exceptions, every hairy animal tail is called a tail. The tail turn was over several decades an important craft branch of the German fur industry , a Glossary calls using even as at times risen to gigantic proportions . The remnants of fur that fell off during fur processing were used for this . After the Second World War it quickly declined in importance; one of the last German tail-twists gave up his self-employed profession in Leipzig at the age of 90 before 1984. In 2009, the now 102-year-old Herta Böttger from Frankfurt stated that she was the only woman in Europe who could still master this craft. She also came from Leipzig, where she had learned the trade from her father in his feudal pig factory. Nothing seems to be known about a tail turning shop that may still exist or be revived outside of Germany.

General

Garnishings of hairy fur tails, the tails, always played a more or less important role in fur fashion. Since the earliest Middle Ages, the most noticeable and most frequent use of the ermine tail on "tailed" ermine clothing. Ermine fur was part of the clothing reserved for the knightly class and the doctors. The “pure white” of the ermine winter fur, also in a figurative sense, has led to it being a symbol of purity and flawlessness for centuries as a mark of princely or judicial power. To this day, the white fur with the characteristic black dots on the tail is part of many coronation regalia .

The materials of the tail Dreher were leftovers, among others, fox fur , rabbit fur , Kaninfellen , goat skins , wolf skins or the like. Tails were also turned from whole goat skins, which were traded under the name "Fuchslinschweife". Around 1900 the otherwise less popular civet cat skins were suddenly in great demand; they were dyed skunk-like, cut into narrow strips and twisted into tails and served as a replacement for the expensive fox tails.

The mechanical equipment of the factories consisted essentially of the same machines as those of the fur trimmers and fur dyers , with the exception of the welding lathe and, to a much lesser extent, however . These were centrifuges , Läutertonnen , Shakes Onnen and color barrels.

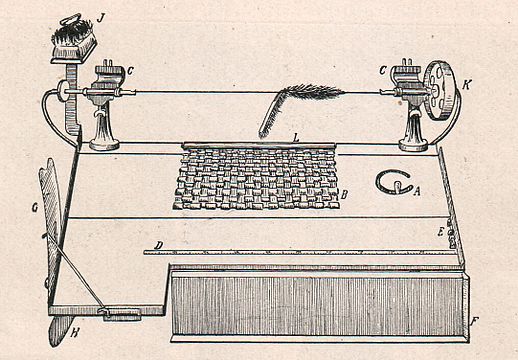

A furrier magazine described the tail and boad lathe after 1900:

- When twisting up boas made of smoky fur, such as bears, wolves, fox tails, etc., a strong string or a wide solid band is usually used as filling, which is coated with dissolved rubber. After the lower end of the boas has been sewn to the cord, the fur tape begins to be rolled up from below. By letting the fur tape roll up tightly with one hand, you can brush the hair down with the other so that as little as possible is stuck between the rings.

- However, if a boa is made of flatter fur, such as pecans or sable tails, it is first necessary to make a filling using a wooden stick, which gives the boa the necessary strength. It is always advisable to first turn the fur band onto the rod as a test to see the effect of the finished boa. If the rod has been found to be of sufficient strength, rub it a little with soap and clamp it in the machine. A strip of atlas or a smooth, firm ribbon is now stretched over the rod with pins and a thread is rolled over it. Then the needles are pulled out, rubber is put on and the boa is turned on. After it has dried sufficiently, the stick is pulled out and the resulting empty space is filled with wool that is the same size as the wooden stick, inserted using a heavy needle. Then the two halves are sewn together and the ends are closed by attaching a suitable piece. Twisted boas must always be carefully combed out and coated several times.

The snake-shaped fur boas and feather boas that ended in a point were particularly popular in the 1880s. Feh-tail boas were relatively cheap compared to those made from ostrich feathers or other natural products, they were often made up to a length of 2.75 meters.

The sleeves, shoulder collars, capes and stoles made of twisted tails were also grateful to wear. Philipp Manes noticed a large scarf that still looked like new after twenty years. In the beginning, the tails were also put together by hand on strings. It was imperative that these cords were made of the best material, that they were perfectly smooth and that they did not contain the slightest knot. So they paid the high price of 3.50 marks for 500 grams of cord at the time.

The tail lathe for the furrier has been described elsewhere as follows:

- When processing the furs, the furrier uses a simple rotating device, by means of which he winds together a roller body that looks like a round brush by winding thin strips of fur from rabbit dewlaps, goats etc. in a spiral. The axis of this cylinder is formed by a hemp thread. The device can be attached to any sewing machine frame and operated using its pedal mechanism.

In his memoirs, the Leipzig tobacco merchant Walter Krausse writes about the founder of his company, the very innovative tobacco merchant Friedrich Erler : “ Ob Gottl. Friedr. Erler also invented the tail lathe, on which another, now independent, industry later built up, I couldn't find out. A machine that is still available at our company and appears to be rather original would suggest this. "

Initially there were only individual tail twists, some larger productions existed in Berlin in the 1870s / 1880s. According to a statement from 1913, however, the tail and boat twists were already “lively buyers of natural frog tails, next to the price-making fur speculators without specialist knowledge, who were already invented at the time”.

The trade in pieces of fur has always been largely carried out by Greek traders who exported the goods they bought in Germany to their home in the two furrier towns of Kastoria and the nearby Siatista . Around 1911, the production of imitation ermine tails and skunks tails was entirely in Greek hands, skunks tails soon made considerable competition for the more expensive feudal tails. A tail industry of its own developed, especially in Leipzig, and in the maximum period after 1900 26 companies were involved in it. The best-known of these were Otto Jähnichen & Co., L. Nomis & Co., Gebr. Jahresling, G. Berger, Buslik G. mb H., Raja Werke AG, etc. Apart from the manufacture of goat tails, the Berlin tail production also relocated Leipzig and from there served the entire world market, the big buyer was initially England, in America people only began to show significant interest in it in the early 1920s. In 1897, however, Max Rabe from Leipzig advertised his twisted squirrel and fox tails and fur tires in an American trade journal. In 1929 there were still 16 welding factories in Leipzig. The companies B. Buslik, Leon Nomis and S. Goldstaub later also gained importance as clothing manufacturers. For many of the companies, the Nazi persecution of the Jews meant the end. The main reporter on the German tobacco industry including the tail turning shop, Philipp Manes, was also transferred from the Theresienstadt ghetto to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp on the last transport and murdered there.

With the decline of the tailed ermine fashion, twisted frog tails became the more important trade item, the frog tail twists formed a separate branch of fur manufacture. " Several thousand hardworking hands " were busy providing the whole world with this special item. The tobacco dyer Wilhelm Prätorius introduced this branch of industry in Leipzig at the end of the 1840s, while his foreman Wilhelm Seidler, who after the early death of Praetorius " also took possession of the business with the hand of the widow Prätorius ", continued the business. The company still existed in 1940, where it was continued under the old name of the head master of the furrier guild Oscar Wencke " in the spirit of the founder ".

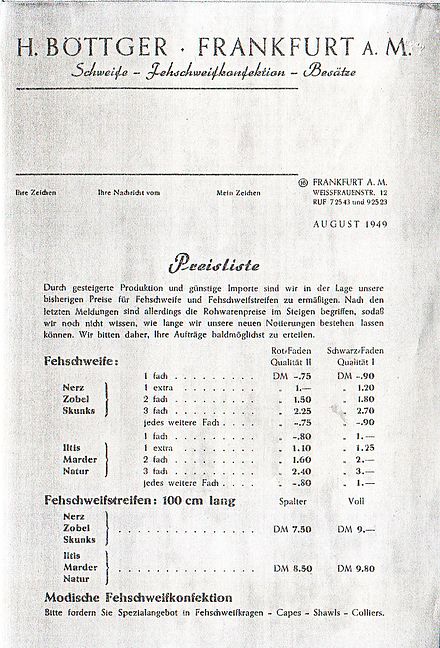

Another particularly important feh-tail turning shop was that of W. Grünreif, who had acquired his knowledge from Wilhelm Praetorius. He was able to keep his business running exclusively with this special work. The parent company in Leipzig employed an average of 300 people in its own factory. The company soon had something of a monopoly in the tobacco industry for small-scale confectionery, with sales of up to 85 percent, especially to England, Italy, Switzerland and the northern states. Because of the increased export share especially after the First World War, a subsidiary was set up in London. After the death of the founder, Robert Töpfer continued the business on a larger scale. Robert Töpfer was also killed in the devastating air raid on Leipzig in 1943, and the business premises with all the warehouses were completely destroyed. His daughter, Herta Böttger, continued the company. During the time of material scarcity, she switched the company to using rabbit waste "after lengthy trials". After the Second World War, the company, now based in Frankfurt am Main, was the last still active tail turning shop in the German Federal Republic.

- Necklaces made of twisted tails with rosettes

The development of the frog tail mills was shown as an example of how much the Leipzig tobacco industry could change and adapt to new needs. With fashion, the level and mode of employment of this specialty industry changed significantly. From the mid-1880s onwards, all of the trophy tails that were commercially available were used for boas. In 1896, the processing of shorter, twisted frog tail necklaces began, which ended in rosettes of trimmings or later branched into several tails. R. Töpfer, the co-owner of the W. Grünreif company, made an invention in 1919 that was important for the production of trousers. It made it possible to use twisted frog tails as a surface to make attractive collars, scarves, capes and sleeves. Since he did not have the process patented, it quickly found imitators.

Up until World War I , most of the raw frog tails were bought in Russia, where there were large miscarriage factories. A comparatively small part was only cut off in Germany. In both cases, the tails were sorted according to the regions of origin. The proceeds from the sale of a tail temporarily covered the dressing costs of the false hide. In the 1920s, Töpfer tried again to persuade the now state-owned Russian fur traders to offer the frog tails separately so that the manufacturers could be supplied with goods as evenly as possible. At that time, the skins were no longer sold so quickly in the trade and remained with the tails, resulting in a shortage of goods for the tail turner, which also led to considerable price fluctuations. The Russians rejected the request on the grounds that "the tails must remain on the skins so that buyers can recognize the provenance of the skins on the tail".

Larger feudal factories processed an astonishing 12,000 tails per day. When these quantities were no longer sufficient, fox tails were used for the same purpose. As early as 1989, the company L. Walters Successor AG colored. in Markranstädt 1,200,100 fox tails, next year there were only 500,000. Initially, the companies had largely specialized in crooks or fox tails, but starting around 1930 they manufactured both products in their factories. At that time people began to eulanize the tails, make them moth-proof. Towards the end of the 19th century, fur necklaces came into fashion, fur shawls in the shape of animals, and they almost completely replaced fur and feather boas.

The frog tails were separated from the raw fur by the tobacco dealer or the dresser before the tanning . The tail turner gave them to dressing , usually also for subsequent dyeing . On the tail lathe, they were then turned 1 to 15 times into tails of various strengths, giving them a fuller appearance. The twisted tails or tail boas were hung in the cellar to dry and straighten their hair and then leveled with scissors. Tails with the highest material consumption were the strongest. In the early years, each starch compartment was charged at a groschen (10 pfennigs). The strips were made up to a meter in length and bought by the trophy tail, which made capes, trimmings, trimmings, etc. from them. The furrier around 1900 also used tail turning in his workshop. The frog tail is two-line, which means the hair goes in two directions. To make it more beautiful, he pulled a string of string through the dampened tail and twisted it. This made the tail look round and the hair fell evenly on all sides. In order not to get too short, he often cut two or three tails into one long tail beforehand.

In the larger companies, the individual operations were specialized, and the finished product had passed through up to ten pairs of hands by the time it was dispatched. There were "girls" who just cut open the leather, called slits. Others sorted the tails together by hair length (smoke) and color (laying women), still others sewed the tails together (seamstresses). More workers made the sewn longer and shorter strips ready for the lathe operator.

The brush ears of the false fur were also used. Colored black, they served as the end of the twisted, imitation ermine tails.

On July 14, 1921, the Vereinigung Deutscher Schweiffabrikanten, e. V. (VDP) was founded to represent the interests of the industry. When it was founded, it had 12 companies, in 1927 there were 34 companies. 10 of the members were based in Leipzig, 24 abroad.

The company Fr. W. Förster , Leipzig, Boa and Schweiffabrik, founded in 1893 , brought one to the novelty exhibition in 1926 in addition to its specialties in feh, fox, goat, foxtail, wolf, opossum and raccoon tails ("scales") new article on the market under the name "Skunksette trim strips", available in all modern colors. - In 1925 the tobacco wholesaler Jonni Wende offered twisted fox tails for 3 to 6 Reichsmarks, natural ones for 4 to 7 Reichsmarks.

Shortly after the beginning of the 1930s, the demand for tails began to decline to an extent that was threatening for the companies concerned. With the help of emigrated employees, but also with the help of Leipzig sweat manufacturers, sweat factories were set up in London, Paris, Brussels and most recently in Prague, while England, formerly a major buyer, had set up customs barriers. In addition, the fashion direction had become unfavorable for the use of tails, instead of small parts, fur jackets and coats were sold. The change could be seen in the drop in tail prices: In the years 1926 to 1931 ½ kilo tails cost around 50 marks (more or less), in 1934 the same goods were available for around 3 to 5 marks, i.e. around the 15th Part of the award that has existed for many years. The proportion of wages now made up more than half of the value of goods. The tail turner also complained that a large part of their orders now came from furriers who were looking for a tail that would match an old, perhaps dyed and faded, old fur necklace - and then possibly sent it back because the furrier did not consider it to be good enough to match the color who felt hair length or quality. The Leipzig fur refiner Walter Starke pointed out around 1939 that when re-dyeing furs, the twisted tails had to be removed beforehand, "twisted tails disintegrated during dyeing".

The Leipzig tail turner Max Schödel describes in 1984 how he made tails , mainly from leftover rabbit fur , despite material problems in the GDR's shortage economy . The appropriately sorted pieces of fur were cut into strips one centimeter wide and sewn together. Such a three-meter-long strip consisted of about 80 pieces, the product twisted from it was then about one meter long. The material prepared in this way was wrapped in damp cloths for several hours to make the leather quicker. The turning was done on the special machine. The thread clamped there was coated with glue, as was the leather side of the fur strip. The two tensioning devices were driven mechanically via a belt transmission, with a step, similar to a foot-operated sewing machine. The work required great care and dexterity so that the strip wrapped itself evenly and tightly around the thread. The maximum length for a tail with full utilization of the machine width was three meters. After taking it out of the machine, the loose hair was pounded out and the fur was dampened. The tail lathe used by Schödel was around 100 years old.

- "Universal workbench with inserted knocking shaft and tail turning device" (1914)

As a knocking machine

use

As mentioned, ermine tails were originally used as a symbol of status and status on clothing made from ermine fur, later often also on clothing made from misfelt , a somewhat lower class clothing. On old pictures and on old sculptures, especially of St. John Nepomuk , patron saint of bridges, on his cloak, the mozzetta made of Fehfell, different sometimes Feh-, sometimes ermine tails can be found.

In more recent times, around the 19th century, fur fashion became more and more bourgeois, it became more affordable, furs were now generally worn with the hair facing outwards, and ermine and misfelt were no longer reserved for high-ranking personalities. By 1900 almost every ermine fur was garnished with tails. There were fur scarves that had up to 14 attached heads ("plastered heads") and tails. Fur necklaces, animal-shaped scarves with heads, paws and tails, were also very fashionable. Since the natural tails were often useless for this, they had to be imitated from leftover fur. Around the 1920s, the twisted tails began to be processed further into collars, capes, scarves and other small parts.

Fur tails have been used to different degrees as pendants on key chains, bags and other everyday objects in the last few decades. In the 1970s, a fox's tail was a symbol for “ chubby ” Opel Manta drivers who used it to decorate their car antennas. Even a bonanza bike wasn't actually complete without a red fox tail at the same time. Given the currently strong demand for fur tails, it is rather surprising that this branch of trade, at least in China, the current main production country for fur, has apparently not been revived (2013).

- Tail uses - twisted tails are hard to distinguish from the natural ones

Foxtail boa. Dancer Therese Elßler

(1808–1878)

annotation

In the fur literature, an "unnatural tail twist when processing fur" is also described. This is not about the tail twisting discussed above, but about the observation that with raw, but especially with tanned skins, the tails often twist in a spiral (screw-like) shape, especially with long-haired tails. This is particularly noticeable with the red fox. It is most likely caused by uneven shrinkage of the tail skin during drying or by twisting out the tail body when removing flesh.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XXI. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1951. Keywords "tail twister", "tail manufacture"

- ↑ Helga Frester: Tail turning - a forgotten trade? In “Brühl” September / October 1984, VEB Fachbuchverlag Leipzig, pp. 29–30, it was quoted: “Max Schödel - Pelzbesatz ” read on his company sign in Leipzig's fur district.

- ↑ Pelzmarkt, Newsletter of the German Fur Association , Frankfurt / Main, August 2009, p. 6.

- ↑ Paul Larisch : Hermelin: Purity and Justice. In “The furriers and their characters”, 1928. Self-published, Berlin, pp. 48–51

- ↑ Note: The Pelzlexikon XXI also calls kid skins ( twisted from whole goat skins, kid skins (foxlin tails) ), these are the skins of young goats. It is not immediately apparent how tails, especially fox tail imitations, can be made from them. A mention of Philipp Manes is even more confusing ?: “ The use of the goat was not limited to the production of blankets, the tail manufacturer devoted all his attention to it, goat tails were used in large quantities for cheap clothing - they only cost a few pfennigs. “Philipp Manes 2: The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story . Berlin 1941 Volume 3. Copy of the original manuscript, p. 18 ( G. & C. Franke collection )

- ↑ a b c Emil Brass : From the realm of fur . 1st edition, publisher of the “Neue Pelzwaren-Zeitung and Kürschner-Zeitung”, Berlin 1911, p. 236 (Greek fur pieces dealers), 238 (Fehschweife), 576 (civet cat fur).

- ↑ a b c d Robert Töpfer: The technique of tail fabrication. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt , Leipzig March 31, 1939, p. 3.

- ^ Paul Larisch / Josef Schmid: Das Kürschner-Handwerk, self-published in Paris . III. Part, Second Revised Edition, p. 56.

- ↑ a b c d BPB: The German Squirrel-Tail Trade - W. Grunreif's Progress . In: The British Fur Trade , April 1927, p. 55.

- ^ A b c d Philipp Manes : The German fur industry and its associations 1900-1940, attempt at a story. Berlin 1941 Volume 1. Copy of the original manuscript, pp. 19, 21-22 ( G. & C. Franke collection ).

- ↑ a b c Without indication of the author: Fehschweife . Reprinted in Die Pelzmotte No. 3, Rifra-Verlag Murrhardt, March 1983, pp. 22-23. Primary source: The fur industry , born in 1926.

- ↑ A. Ginzel: Machines and apparatus for the refinement of tobacco products . In: "Der Rauchwarenmarkt" No. 3/4, Leipzig January 16, 1942, p. 7

- ^ Walter Krausse: Fifty years as a merchant in the imperial trade fair city of Leipzig . Self-published Leipzig April 1941, p. 60. Note: Erler, who had previously worked independently as a furrier and retailer, founded the fur dyeing company Sieglitz & Co in 1876 together with the chemist Adolph Sieglitz, and later the seal brown dyeing factory Erler & Co, which he soon gave up. The parent company ran under the name of the company's founder Friedr until after the Second World War. Erler.

- ^ H. Werner: The furrier art. Publishing house Bernh. Friedr. Voigt, Leipzig 1914, p. 25.

- ↑ Advertisement in: Cloaks and Furs No. 10 . New York, April, 1897, p. 47. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Kurt Nestler: Tobacco and fur trade . Max Jänecke Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1929, p. 8

- ↑ Carl Hülsse Rauchwaren - Fehschweiffabrik Wilh. Seidler . In Walter Lange (Hsgr.): The 100 year old Leipzig , "REGE" Deutscher Jubiläums-Verlag, Leipzig, 1928/1929, p. 239.

- ^ "B / B" [Rolf Böttger]: Company history retrospect on a letterhead from H. Böttger KG, Frankfurt am Main, Oberweg 46 office, undated, 2 sheets, G. & C. Franke collection (a letter enclosed among other things According to February 17, 1974, the author is Rolf Böttger, his manuscript for a lecture at the Federal Pelzfachschule in Frankfurt am Main → Fehschweife, letter Rolf Böttger, Frankfurt, to Richard Franke, Murrhardt, 1974 ).

- ↑ Christian Franke / Johanna Kroll: Jury Fränkel ’s Rauchwaren-Handbuch 1988/89 . 10th revised and supplemented new edition. Rifra-Verlag, Murrhardt 1988, p. 181 .

- ↑ Robert Töpfer: Situation of the tail production . In: Die Pelzkonfektion , February 1930, p. 27.

- ^ Paul Pabst: The tobacco shop . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the High Philosophical Faculty of the University of Leipzig, Berlin 1902, p. 79.

- ↑ Paul Cubaeus, Alexander Tuma: The whole of Skinning . 2nd revised edition, A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna, Leipzig 1911. pp. 317-318

- ↑ Dr. Paul Schöps among others: Semi-finished products from Fellwerk . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , Vol. X / New Series 1959 No. 2, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., P. 62

- ↑ Heinrich Hanicke: Handbook for furrier . Published by Alexander Duncker, Leipzig 1895, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Gisela Unrein: A master furrier from Brühl remembers (VI) - In conversation with August Dietzsch . In Brühl No. 29, May 3, 1988, p. 29 ISSN 0007-2664

- ^ Gottlieb Albrecht: The fur market of Leipzig with special consideration of its tobacco trade . Inaugural dissertation at the Faculty of Law and Economics of the Thuringian State University of Jena. Bottrop 1931, pp. 25-26. Note: The entry in the register of associations at the Leipzig District Court took place on October 18, 1921.

- ^ New items exhibition of the Reichsbund der Deutschen Kürschner . In: Kürschner-Zeitung No. 15, Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, May 21, 1926, p. 556.

- ↑ Jonni Wende company brochure, Rauchwaren en wholesale, Hamburg, Düsseldorf, Leipzig, New York, August 1925, p. 14.

- ↑ From the circles of the fur industry: The struggle for existence of the tail industry . In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 28, Leipzig, April 11, 1934.

- ↑ Walter Starke: Guide for the furrier with a price list . Leipzig, undated, probably 1938, p. 11 (→ table of contents) .

- ↑ einestages.spiegel.de: Bonanza wheels: pornography and fox tail . Retrieved January 8, 1913.

- ↑ K. Toldt: Unnatural tail twist when processing fur . Publishing house Dr. Paul Schöps, Leipzig 1937 → Book cover .