Marcus Harmelin

| Marcus Harmelin

|

|

|---|---|

| legal form | Sole proprietorship, OHG |

| founding | 1830 |

| Seat | Leipzig , London |

| Branch | Tobacco and bristle trade |

The tobacco goods trading company Marcus Harmelin was connected to the Leipziger Brühl for 120 years, probably longer than any other company . The name Harmelin, probably an erroneous spelling of the royal fur ermine , points to an even longer tradition of the fur trade in the family. The quarter around Leipziger Strasse Brühl was once one of the three world trade centers for tobacco products (skins).

According to the family tradition of Marcus (Mardochai) Harmelin (* 1796: † 1873), the company's founder was when he was awarded the brokerage position of his father Jacob (* 1770; † 1825). The company had its heyday under Joachim (* 1843 - † 1922) and his son Moritz (* 1868 - † 1923). For racial reasons, the company of the Jewish family under Max Harmelin (* 1895, † 1951) was liquidated by the National Socialists. The history of the company largely reflects the ups and downs until the fall of the once mighty fur market around the Leipziger Brühl.

Company history

The Harmelin family comes from the then Polish town of Brody (now Ukraine), and they had a fur trade there as early as 1750. In Lesznower Gasse, Marcus had a “handsome building” built with business premises and an apartment. Since 1779, Brody had been a free trade town with preferential tariffs and a predominantly Jewish population. Like Nizhny Novgorod and Irbit , the “ fur city ” was a main hub for Eastern European tobacco products.

Jacob Harmelin was the first family member to visit the Leipzig Trade Fair. In 1818, just three years after the Jews were admitted to this post in Leipzig, he became a mess broker (Messmäkler) and thus an auxiliary official of the city with special rights. He set up a makeshift warehouse in the house at Zum Blauen Harnisch , Brühl 71 (at that time No. 490/96). The Brody Jews had their own prayer room in the building. His main trade items were the inexpensive hare skins , while otherwise more valuable types of skin were traded at the Brühl . There was not much money to be made with it, but he made an important entry into the Leipzig fur market.

In 1830, Marcus got his late father's brokerage position in Leipzig. In 1845 he moved his apartment and warehouse to the house at Ritterstraße 20 (later No. 38) belonging to the market helper Karl Heinrich Jentzsch , to the first floor of the Commichau packer . It was not until 1837 that a state law allowed Jews to settle in Saxony. It was only because Marcus was a broker that he was able to establish Leipzig's first Jewish tobacco shop. His son-in-law Isaack Barbasch († August 1, 1895), son of a Brodyer tobacco shop , became a partner . In 1868, Joachim Garfunkel , who was married in, moved to Leipzig with his young wife Blume (* August 4, 1843) in the house "Zum Heilbrunnen", Brühl 71 (later No. 35), owned by the tobacco merchant Nathan Haendler , where the Leipzig business premises were also relocated. The headquarters stayed in Brody for a long time, partly because of the proximity to the fur supplier Russia, and also because of the still existing anti-Jewish attitude of Leipzig politics. However, as the rail network expanded, the classic fur hubs of the east, including Brody, lost their importance. In 1873 Marcus Harmelin died in Brody while he was about to close his camp there. The year before he had been naturalized in Leipzig and entered in the commercial register.As a Jew, he had to show a guarantee of 4,000 thalers in cash for this, although he had had quarters and storage facilities in the city for decades and had been free to trade since 1861. Isaack Barbasch left the company by mutual agreement in 1868. He founded his own company under his name in Leipzig, which he continued until his death.

The economically most successful years lay between 1880 and 1914. Joachim Garfunkel and his son Joseph had been given responsibility for purchasing in Russia, and Joachim had been attending the trade fair in Nizhny Novgorod regularly since the 1850s. Joseph had taken over this from 1889. He often drove further east than his father, in 1892 to Irbit, the world's largest fur market at the time. In addition to the skins, bristles were a specialty item of the company, and Harmelin was the most important supplier in Europe. At the instigation of the company, the City Council of Leipzig decided on May 31, 1890 to hold two special markets for bristles in addition to the previous bristle fairs. From 1880 until the liquidation, the company address was Brühl 47 (Krafts Hof). Joachim and Moritz Harmelin began to invest economic surpluses in real estate. First they bought the houses at Brühl 47 and 51 as well as Richard-Wagner-Straße 8. On the "strip" acquired in 1908, the architect Emil Franz Hänsel built the houses Nikolaistraße 57 to 59 ( Harmelin-Haus ). The building complex comprised the largest inner courtyard of all, the so-called "courtyards" typical of many tobacco shops' houses, but this was called the "Rauchwarenhaus". The Brühl was largely a pure business district, the owners of the company lived at Nordplatz 2, in one of the preferred residential areas. Moritz Harmelin was appointed a full-time member of the Commercial Statistics Advisory Board of the Reich Statistical Office in Berlin in 1907, and he regularly attended its meetings. The Harmelin company was one of the founding members of the Association of Leipzig Tobacco Companies, which was registered with the Royal District Court in 1909 .

Max Harmelin took over the company after Joachim and Moritz Harmelin died in 1922 and 1923 during the difficult times of hyperinflation . The tobacco industry was in a general recession and the bristle trade practically collapsed. In 1920 the company also merged with Ostrabor Rauchwaren & Borsten GmbH. merged, from which it was only able to separate again in 1930. The substantial real estate ownership helped bridge the difficult period in which many other tobacco shops had to give up. In 1925, Max Hermelin had shops built on the attractive business side of Richard-Wagner-Straße, which he rented out, followed by the eastern half of the same property in 1929. In the mid-1920s, the Brühl experienced a new, very significant boom and the company also recovered.

In 1930, in the year of the 100th anniversary, the facades of the houses Brühl 47 and 51 were renewed and a commemorative publication was published. The Marcus Harmelin Foundation was established for travel grants or similar further training measures, alternately for civil servants from the city of Leipzig and Leipzig merchants and employees, preferably the tobacco shop.

In December 1933, after the National Socialists came to power, Max Harmelin joined the Reich Association of Jewish Front Soldiers; in June 1935 he applied for the cross of honor for his service at the front in World War I. In the end he only managed to leave the country “on time”. In the spring of 1933, the Saxon Minister of Justice imposed a ban on Max Bruder, the lawyer Wilhelm Harmelin. He joined the company as a partner. In August 1935 Wilhelm was accused of “ racial disgrace ”. He was sent to the Sachsenburg concentration camp near Chemnitz. He was released after nine months. During the imprisonment the company was hit in its economic nerve, import restrictions brought the trade in fur and bristles almost completely to a standstill. As a result, the company limited itself primarily to property management and rental. In March 1939 Wilhelm Harmelin, the managing director and partner of Ostrabor Ltd. London was to leave for England. The Leipzig company was liquidated as a Jewish company.

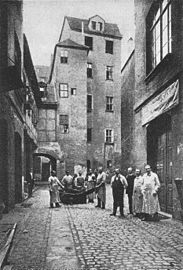

"Krafts Hof" decorated with furs

( German Gymnastics Festival 1913)

- Façade decoration on the Harmelin House (photos from 2003)

See also

literature

- Josef R. Ehrlich: The way of my life - memories of a former Hasid . Rosner, 1874 . Last accessed October 1, 2018. --- Joseph Ehrlich, then a student of Brodyer " Yeshiva ", has an impressive description of life "in the house of wealthy muskrat leave Trader Marcus Hermelin" [Harmelin] in the Leznower alley early 1850s .

Web links

supporting documents

- ↑ a b c d e f g Wilhelm Harmelin: Hundred Years of Marcus Harmelin 1830-1930 . Festschrift of the company.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Walter Fellmann : Family Harmelin . In: Ephraim Carlebach Foundation (ed.): Judaica Lipsiensia. Edition Leipzig 1994, pp. 271-273. ISBN 3-361-00423-3 .

- ^ A b c Wilhelm Harmelin: Jews in the Leipziger Rauchwarenwirtschaft. In: Tradition , No. 6, December 1966, Verlag S. Bruckmann, Munich, pp. 249–282.

- ↑ Barbara Kowalzik: Jewish working life in the inner Nordvorstadt Leipzig 1900-1933. Leipziger Universitätsverlag 1999, p. 120.

- ↑ juden-in-sachsen.de: Harmelin, Max. ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 7, 2015

- ↑ www.juedischesleipzig.de: Monika Gibas, Cornelia Briel, Petra Knöller, Steffen Held: Boycotted and "Aryanized": The example of the M. Joske & Co. department store and the Marcus Harmelin tobacco shop. Leipzig 2007. Accessed November 7, 2015.

- ^ Wilhelm Harmelin: Brody, the old fur town in Galicia - its importance for the Leipzig tobacco industry . In: Das Pelzgewerbe , 1966 No. 4, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., P. 181.