Otto III's prayer book

The Prayer Book of Otto III. , also as the royal prayer book of Otto III. or known as the Pommersfeld prayer book , is a medieval manuscript that is one of the main works of Ottonian book illumination . The manuscript has been kept in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich since 1994 under the signature Clm 30111 . The between 984 and 991 and for the private use of the young King Otto III. certain manuscript is the only surviving prayer book of a king of the Ottonian period. The manuscript's texts and book art convey a monastic ideal of rulers.

description

The book

With a format of 15 × 12 cm, the codex is unusually small, but it is extremely well equipped. The 44 parchment leaves are written on with gold ink on a painted purple ground . The book decoration consists of five full-page miniatures and a total of 25 small gold initials with red outlines and blue inner backgrounds. The script is a regular Carolingian minuscule ; some headings are done in Capitalis rustica . The writing surface measures 9.5 × 7.5 cm and is framed by a vermilion bordered gold strip. The average of 14 to 15 lines per page were drawn with a stylus.

Since 1950 the manuscript has been bound in two wooden book covers covered with blue, patterned velvet, which are held together by two buckles with leather loops. This binding replaced a black velvet binding, which was also not original. The book block has a gilt edge on why a rebinding in Baroque is suspected.

The manuscript is largely complete. It contains all the essentials that can be expected in a prayer book for the private devotion of a lay person. However, individual sheets of paper may have been lost, although care was taken to keep the prayer book in a complete condition. On fol. 31r an isolated end of prayer has been carefully deleted above; the beginning of the prayer must have been on a lost cover sheet. Presumably, the outer double blade is at position fol. 31-36 have been lost; this is supported by the fact that the situation closes today with a rubric for a morning prayer, which is based on fol. 37r, however, no morning prayer follows. The layout is I + 2 IV + II + IV + 2 III + I.

The text

The codex is a king's private prayer book and therefore belongs to a type of manuscript that has seldom been handed down. Besides the prayer book of Otto III. only the prayer book of Charles the Bald (Munich, Treasury of the Residence , inv.no.4) and a psalter that was written for the private use of Ludwig the German (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. theol. lat. fol. 58 ). There was no fixed canon or a text template for private prayer books.

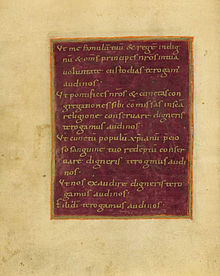

After the first miniature, the manuscript begins with Psalms 6 , 31 , 37 , 50 , 101 , 129 and 142 , the so-called penitential psalms . The belief expressed in the penitential psalms was that man was sinful and that his distance from the exalted majesty of God was irreconcilable, so that he needed saints and angels as mediators and intercessors. After a rubric there follows an All Saints' Litany ; A total of 81 saints are called upon for assistance. The intercessions of the litany cover many concerns, including peace and unity, true repentance, and the remission of sins. For himself, the praying implores contrition of heart and the gift of tears, protection from eternal damnation, God's mercy and in awareness of his royal rank and the responsibility of the ruler:

“Ut me famulum tuum et regem indignum et omnes principes nostros in tua voluntate custodias, te rogamus audi nos”

"That you guard me, your unworthy servant and king, and all our princes, as it is your will, we ask you, answer us."

After the three times Kyrie and the Lord's Prayer , four closing prayers and the second miniature follow. Fol. 21v, the reverse of the Majestas, is blank, but shows the purple inscription on the other side. On fol. 22r is followed by an introduction to the prayer, which is followed by prayers to the saints, the apostles, Mary, God the Father, Christ, the Holy Spirit and the Trinity as well as an indulgence prayer, a morning prayer, a kyrie and collection prayer , prayers for worshiping the cross and prayers for entering and leaving the church connect. After the last prayer, it says Explicit Explicit liber and the blessing Tu rex vive feliciter. Amen (You, King, live happily. Amen). The manuscript closes with the dedication picture and the dedication poem.

The prayers were not written specifically for the recipient of the manuscript. Several prayers, such as that to God the Father fol. 26v, are taken from Libellus precum of the late 8th century, ascribed to Alcuin . The compilation of the prayers in Otto III's prayer book. is without a direct model and does not correspond to any surviving medieval prayer book.

In addition to the actual text of the prayer book, the codex on fol. 1r., Which was originally empty, contains the ownership entry of a Duriswint in a script dated to the 11th century; the same hand wrote an extract from the genealogy of Christ on the last page.

The miniatures

Crucifixion and Deesis

The first miniature shows the crucifixion on the verso side , flanked at the bottom by Mary and the Evangelist John , at the top by the personifications of Sol and Luna . The recto side is divided into two registers. In the upper part, Christ stands in the sense of Deesis between John the Baptist and Mary, who turn to him. Below is a bareheaded young lay person in a prayer position between Saints Peter and Paul , identified by their attributes . He wears a garment trimmed with gold braids, over it a short cloak called chlamys , the purple color of which identifies him as a king. Insignia, such as a crown, are missing. In the text accompanying the crucifixion, the person praying asks the rex regis ( King of kings , meaning Christ) for the enlightenment of heart and body in the sense of following the cross. The prayer is:

“Deus qui crucem ascendisti et mundi tenebras inluminasti tu cor et corpus meum inluminare dignare qui cum patre et spiritu sancto vivas et regnas deus per omnia secula seculorum. Amen."

“God, who climbed the cross and enlightened the darkness of the world, want to illuminate my heart and body, who you, God, live and rule with the Father and the Holy Spirit for eternity. Amen."

The prayer is composed of contemplation and request and integrates the viewer into the miniature. The young king depicted on the opposite side is at the same time the observer of the Succession of the Cross and an object of personal observation.

Otto in Proskynesis and Maiestas

The verso shows the same young king as the Deesis picture in deep Proskynesis , a gesture of humble adoration. He wears the purple lamys and a breast band with gold interweaving, which may have been influenced by the Loros of the Byzantine imperial costume, but no regalia. It lies in front of a stately architecture with a central archway and a tower towering above it, in which a figure stands with a raised sword. His gaze is directed to the Maiestas depicted on the recto side. The swordtail behind him is dressed in a blue tunic and purple lamys, identical to the king. Like the king, he is gifted with the vision of the Maiestas.

On the opposite side, Christ is enthroned in the mandorla held by two angels . He is sitting on a golden segment of a circle, his feet resting on a rainbow. He is dressed in a green-pink tunic with a purple clavi (stripes that are derived from the costume of Roman nobles) and a golden pallium . The right hand is raised in blessing, in his left hand he is holding a book. There are four golden stars in the corners of the image. Christ's gaze is on the King who persists in prayer. The Maiestas is not a Maiestas Domini , but an Engelmaiestas. It stands for the exalted Son of God who appeared in the vision.

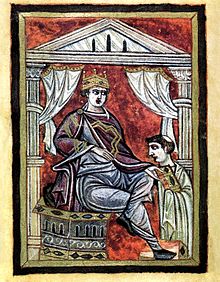

Dedication image

The final picture, opposite of which is a dedication text on the recto, shows the king enthroned. Over the tunic he wears the purple lamys with gold ornaments and a four-sided, box-shaped crown. He sits cross-legged on an ornate box throne under a pediment supported by two columns. From the right, a canon in simple clothes, who is represented significantly smaller in terms of the perspective of meaning and presents the book, approaches him . Opposite the picture is the hexametric dedication poem:

“Hunc satis exiguum, rex illustrissime regum / Accipe sed vestra dignum pietate libellum / Auro quem scripsi, signis variisque paravi / Multiplici vestro quia mens mea fervet amore / quapropter suplex humili vos voce saluto / Et precor, ut tibi vita salus perporeque potestas / Tempore potestas sit vite, donec translatus ad astra / cum Christo maneas, virgeas cum regibus almis ”

“Accept, exalted King of Kings, this humble little book, but worthy of our admiration for you, which I have written in gold and decorated with various pictures, because my heart burns with love for you. Therefore I greet you on my knees with humble words and ask that you will receive salvation and lasting power for your life until you will be caught up in the stars with Christ together with the kings in heaven. "

Art historical findings

Dating and localization

The collection of saints in the litany contains numerous saints who come from the diocese of Mainz and had their focus of veneration there, including Ferrucius , Albanus , Theonestus and Aureus , which suggests that they originated in Mainz . It is uncertain whether the codex was written at the cathedral or in the monastery of St. Alban . The recipient of the manuscript is not named in this, which made dating difficult. Due to his depiction in the Deesis picture as a beardless youth and some rubrics aimed at a still young king, only Otto III., Heinrich IV. And his sons Heinrich V and Konrad were considered as recipients . From the intercession "that you preserve me, your unworthy servant and king and all our princes, as it is your will" it was concluded that the king must have ruled independently at a young age, which is why the sons of Henry IV were rejected as recipients because they only attained royal dignity as adults. Due to the Byzantine influence in the miniatures, Otto III. Descent from the Byzantine Theophanu and the fact that her chancellor and confidante Willigis was Archbishop of Mainz, the recipient was identified as Otto III. and the dating between his coronation as king in 983 and the death of Theophanu in 991. The palaeographical dating to this period is also certain: the writer of the prayer book also made a gospel book, which today only survives as a fragment (Epinal, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 201) which is also localized to Mainz. Hartmut Hoffmann also identified him as one of three writers in the Evangelistar BAV Reg. Lat. 15, now kept in the Vatican , in which he only follows fol. 1r and 2v have written. According to Hoffmann, the master of the Registrum Gregorii , who is perhaps the best illuminator of Ottonian art , also worked on this evangelist .

Archbishop Willigis is presumed to be predominantly the commissioner of the prayer book. Hoffmann pointed out, however, that the scripsi in the dedication poem cannot be translated as I have had it written and that Willigis would certainly have found more talented painters and better scribes for such a gift. The donor of the prayer book appears in the dedication picture as a cleric, and according to the wording he was very familiar with the king. Based on this, Hauke considers that the prayer book could have been a gift from Bernwards von Hildesheim . Bernward had been appointed tutor of Otto in 987 by Theophanu, possibly at the suggestion of Willigis, who had ordained him deacon and priest around 985, which he remained until his ordination as Bishop of Hildesheim in 993. Otto and Bernward remained friends until Otto's early death.

The pictorial program of the manuscript

There was no specific decoration program for private prayer books, in contrast to the other private prayer and devotional book, the Psalter. Most of the surviving early medieval prayer books have no images or only have more or less elaborate initials. Text and miniatures of Otto III's prayer book. follow a certain plan, the miniatures are an integral part of the manuscript. They structure the handwriting, at the same time they serve for devout contemplation. The content of the miniatures is based on the medieval understanding of rule centered on Christ, which understands kingship as an office conferred by God.

Winterer points out that the role of the abbot, as laid down in the Rule of Benedict , was also seen as a guideline for royal action. That is why the influence of monastic meditation literature, namely the figure poem De laudibus sanctae crucis by Hrabanus Maurus , can be seen several times in the prayer book . Like this work, the prayer book begins with the crucifixion and a representation of the ruler. Also in the picture of the king praying in Proskynesis an influence of the pictorial poem Hrabanus' can be determined, which contains a miniature of the poet worshiping the cross in this posture. The cross, which is venerated by Hrabanus and in the adoration image in the prayer book of Charles the Bald, which is also influenced by Hrabanus' pictorial poem, is replaced by Christ in Otto's prayer book, who promises Otto co-rule in heaven. Only with the image of the throne does the king leave the humble, monastic role. The pictures in the prayer book show the king in his enlightenment process: After the request for enlightenment, as expressed in the text of the crucifixion picture, the humble representative of Christ on earth is granted the vision of Christ in the devotional picture. In the final picture, the king accepts the manuscript, with the dedication text opposite emphasizing his piety and enlightenment and wishing him constant royal power. The pictures therefore reflect ideas of royal rule.

Deesis

The Deesis motif comes from Byzantium; the representation in Otto III's prayer book. is the earliest example of this type of picture in occidental illumination. The request with which Mary and John turn to Christ in the miniature must be understood as an intercession for the ruler, who is included in the heavenly hierarchy through his depiction in the lower picture field, and his rule, which is under Christ's protection. The apostles Peter and Paul are in the miniature as personal patrons of Otto, but also have a reference to Rome. They are representatives of the church, patron saints of the city of Rome and thus the guarantors of its rule. The background colors of the Deesis representation are also significant: The actual Deesis stands in front of a deep dark blue, which characterizes the heavenly spheres; the purple ground of the lower register marks the sphere of the ruler appointed by God.

Proskynesis and Maiestas

The rather rare distribution of an image of worship on two opposite pages already appeared in the prayer book of Charles the Bald and appears around the same time as the prayer book of Otto III. in the Everger Epistular .

Proskynesis was unusual in Western court ceremonies, but it was part of the liturgy in the veneration of the cross. According to the Mainz King's Order , which passed on the coronation ceremony of the East Franconian Empire , the king was lying in a cross pose in front of the altar during the litany. As an iconographic motif, Proskynesis comes from Byzantium as a visible expression of the thought that the ruler acts as a vassal and representative of Christ. Proskynesis in front of the cross in western illumination is in turn influenced by the depiction of Hrabanus Maurus in his figure poem De laudibus sanctae crucis .

An allusion to a city could be hidden in the architecture, namely Aachen. This is particularly supported by the unusually prominent wall character, which does not correspond to the conventional formulas for sovereignty for interiors, such as columns, gables and curtains. In contrast, Saurma-Jeltsch sees the architectural representation as the surface projection of a church building in which the prayer process takes place. The arcade arch serves both as a national emblem and as a sign that the events were taking place in the center of the room in which the sword-bearer stands behind the praying king. Saurma-Jeltsch suspects that the sword-wielding figure could be a doubling of the ruler. Swordtails are more common as accompanying figures in depictions of rulers, but not in devotional images. The sword was a symbol of rule, taking over the sword during the coronation ceremony made the king a “defensor ecclesiae”, a defender of the faith.

The Majestas depiction shows the influence of Byzantine depictions of the Ascension; Lauer refers, for example, to the dome mosaic in Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki , in which the posture of Christ and the angels is almost identical. Through his humble prayer, the king receives the vision of Christ giving him his blessing. The gaze directed at Christ lifts the king up despite the humility - he is evidently worthy of the contemplation of Christ.

Dedication picture and dedication poem

Compared to the other miniatures in the manuscript, the image of the throne appears less successful; possibly the painter, who was able to fall back on familiar motifs for the Crucifixion, Deesis and Majestas, was confronted with an unfamiliar task because Byzantine art does not know dedication images. It is noticeable that the aedicula , characterized by its white color as marble , under which the king is enthroned, overlaps the frame. Lauer thinks it is possible that the painter copied them from another context. The clergyman who hands over the book is inserted inorganically and has no eye relationship with the king. The king's posture and gestures do not match, the king is not sitting firmly on the throne, but seems to be balancing on its front edge. The painter may have drawn on various models. In the type, an influence of the second dedication image from a manuscript of the De laudibus sanctae crucis (Vatican, BAV, reg. Lat. 124), which was in Mainz when the prayer book was written, is possible.

Through the aedicule, the dedication image is approximated to an image of a ruler . The motif of the aedicula was occasionally used in pictures of rulers, more often in pictures of evangelists. The painter could also have adopted the aedicule from Carolingian book illumination. The figure of the king also shows references to Carolingian book illumination; his posture is closely related to that of the evangelist Luke the Lorsch Gospel, even the folds under or behind the hip.

history

Otto III. probably used the prayer book until the end of his life. After the death of Otto III. in 1002 the manuscript may have come into the possession of one of his sisters who headed important women's colleges. The name entry of Duriswint, about which is no longer known, could have been made in one of these pens. Later, the exact time is not known, the manuscript came into the possession of the Counts of Schönborn and was kept in the private apartments of the Counts at Weissenstein Castle in Pommersfelden before it came to the castle library under the signature Hs. 2490.

In 1847 Ludwig Konrad Bethmann reported for the first time in an essay about the manuscript, the recipient of which he assumed was Heinrich IV .

In 1897, Joseph Anton Endres and Adalbert Ebner (1861–1898) provided the first detailed description, which continued to be attributed to Heinrich IV. In 1950 the Codex was restored and rebound, attempting to restore the original condition that had been changed when it was rebound. The identification of Otto III. Carl Nordenfalk (1907–1992) received the manuscript in 1957 .

In 1994 Karl Graf von Schönborn-Wiesentheid sold the manuscript for 7.4 million German marks to a funding coalition from the Federal Republic of Germany, the Cultural Foundation of the Federal States , the Free State of Bavaria and the Bavarian State Foundation in order to be able to use the proceeds to renovate Pommersfelden Castle. Since then, the codex has been in the Bavarian State Library under the signature Clm 30111.

facsimile

Otto III's prayer book was made available to a wider public as a facsimile in 2008 . The codex is also available in digital form from the Bavarian State Library on the Internet.

literature

- Wolfgang Irtenkauf : The litany of the Pomeranian royal prayer book. In: Studies on illumination and goldsmithing in the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Hermann Karl Usener. Publishing house of the art history seminar at the University of Marburg an der Lahn, Marburg 1967, pp. 129-136.

- Hartmut Hoffmann : Book art and royalty in the Ottonian and early Salian empires (= writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica . Volume 30). Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-7772-8638-9 .

- Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on the Ottonian Mainz book painting. Dissertation Bonn 1987.

- Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (Ed.): Otto III's prayer book. Clm 30111. (= Patrimonia. Volume 84). Bavarian State Library, Munich 1995.

- Sarah Hamilton: Most illustrious king of kings. Evidence for Ottonian kingship in the Otto III. prayerbook. In: Journal of Medieval History 27, 2001, pp. 257-288.

- Klaus Gereon Beuckers : The Ottonian donor image. Image types, motives for action and donor status in Ottonian and Early Sali donor representations. In: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.): Die Ottonen. Art - architecture - history. Imhof, Petersberg 2002, ISBN 3-932526-91-0 , pp. 63-102.

- Christoph Winterer: Monastic meditation versus princely representation. Thoughts on two profiles of Ottonian book illumination. In: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.): Die Ottonen. Art - architecture - history. Imhof, Petersberg 2002, ISBN 3-932526-91-0 , pp. 103-128.

- Elisabeth Klemm: The Ottonian and early Romanesque manuscripts of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek . (= Catalog of the illuminated manuscripts of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich. Volume 2). Reichert, Wiesbaden 2004, pp. 222-223, no. 202 ( digitized version ).

- Lieselotte E. Saurma-Jeltsch : The prayer book Otto III. To the ruler as an admonition and promise into eternity. In: Frühmedalterliche Studien 38, 2004, pp. 55–88.

-

Otto III's prayer book Commentary on the facsimile edition of the manuscript Clm 30111 of the Bavarian State Library in Munich. Facsimile-Verlag, Lucerne 2008, ISBN 978-3-85672-115-2 , therein:

- Hermann Hauke: The prayer book of Otto III. History, codicological and content description. Pp. 13-62.

- Elisabeth Klemm: Commentary on Art History. The book type - the early medieval prayer book. An overview. Pp. 13-62.

Web links

- Digitized at the Bavarian State Library

- Entry in the online catalog of the Bavarian State Library

- Iconographic indexing of the miniatures in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database , with links to the digital edition of the Bavarian State Library

Remarks

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ The digitized version of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek shows a different cover. Hermann Hauke, Otto III's prayer book. , Luzern 2008, p. 25 mentions that the velvet cover from 1950 shows strong signs of wear.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Elisabeth Klemm: Otto III's prayer book. (= Patrimonia Vol. 84) 1995, p. 40.

- ↑ Elisabeth Klemm: Otto III's prayer book. (= Patrimonia , Vol. 84). 1995, p. 41.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 27.

- ↑ Sarah Hamilton: Most illustrious king of kings. Evidence for Ottonian kingship in the Otto III. prayerbook . In: Journal of Medieval History Vol. 27, 2001, pp. 257–288, here: p. 271.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Sarah Hamilton: Most illustrious king of kings. Evidence for Ottonian kingship in the Otto III. prayerbook . In: Journal of Medieval History Vol. 27, 2001, pp. 257–288, here: p. 266.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ Christoph Winterer: Monastic Meditatio versus Princely Representation. Considerations on two profiles of Ottonian book illumination in: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.); The Ottonians. Art - Architecture - History , Petersberg 2002, pp. 103–128, here: p. 127.

- ^ Lieselotte E. Saurma-Jeltsch: The prayer book of Otto III. To the ruler as an admonition and promise into eternity . In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 38, 2004, pp. 55–88, here: p. 75.

- ^ Lieselotte E. Saurma-Jeltsch: The prayer book of Otto III. To the ruler as an admonition and promise into eternity . In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 38, 2004, pp. 55–88, here: p. 74.

- ↑ Critically edited by Gabriel Silagi, Bernhard Bischoff (Ed.): Die Ottonenzeit, Part 3 (= Monumenta Germaniae Historica Poetae Latinii Medii Aevi , Volume 5.3). Munich 1979, pp. 633–634 No. 4: Dedication of Otto III's prayer book. .

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book , Lucerne 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Wolfgang Irtenkauf: The litany of the Pommersfeld royal prayer book in: Studies on illumination and goldsmithing of the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Hermann Karl Usener , Marburg 1967. p. 129.

- ↑ Elisabeth Klemm: Otto III's prayer book. (= Patrimonia Vol. 84). 1995, p. 73.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Hartmut Hoffmann: Book Art and Kings in the Ottonian and Early Salic Empire , Stuttgart 1986 ( Writings of Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Volume 30), p. 261; Ulrike Surmann, in: Dies., Joachim M. Plotzek (Ed.): Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Liturgy and devotion in the Middle Ages. [Exhibition catalog Erzbischöfliches Diözesanmuseum Köln], Stuttgart 1992, p. 88, doubts the registrum master's authorship, but acknowledges his influence.

- ↑ Hartmut Hoffmann: Book Art and Kings in the Ottonian and Early Salian Empire , Stuttgart 1986 ( Writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica , Volume 30), pp. 235–236.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 57.

- ↑ Hans Jakob Schuffels: Bernward Bishop of Hildesheim. A biographical sketch. In: Michael Brandt / Arne Eggebrecht (eds.): Bernward von Hildesheim and the age of the Ottonians , Volume 1, Mainz / Hildesheim 1993, pp. 29–43, 34.

- ^ Elisabeth Klemm: The book type. The early medieval illuminated prayer book , Lucerne 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Elisabeth Klemm: The book type. The early medieval illuminated prayer book , Lucerne 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Elisabeth Klemm: The book type. The early medieval illuminated prayer book , Lucerne 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Elisabeth Klemm: The book type. The early medieval illuminated prayer book , Lucerne 2008, p. 100.

- ↑ Christoph Winterer: Monastic Meditatio versus Princely Representation. Considerations on two profiles of Ottonian illumination in use in: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.), Die Ottonen. Art - Architecture - History , Petersberg 2002, pp. 103–128, here: p. 126.

- ↑ Christoph Winterer: Monastic Meditatio versus Princely Representation. Considerations on two profiles of Ottonian illumination in use in: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.), Die Ottonen. Art - Architecture - History , Petersberg 2002, pp. 103–128, here: p. 127.

- ^ Klaus Gereon Beuckers: The Ottonian donor image. Image types, motives for action and donor status in Ottonian and Early Salian donor representations In: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.), Die Ottonen. Art - Architecture - History , Petersberg 2002, pp. 63–102, here: p. 73.

- ^ Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on the Ottonian Mainzer Illumination , Bonn 1987, p. 65.

- ↑ Elisabeth Klemm: Otto III's prayer book. (= Patrimonia Vol. 84). 1995, p. 58.

- ^ Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on the Ottonian Mainzer Illumination , Bonn 1987, p. 36.

- ↑ Elisabeth Klemm: Otto III's prayer book. (= Patrimonia Vol. 84). 1995, p. 59.

- ^ Lieselotte E. Saurma-Jeltsch: The prayer book of Otto III. To the ruler as an admonition and promise into eternity . In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 38, 2004, pp. 55–88, here: pp. 74–75.

- ^ Lieselotte E. Saurma-Jeltsch: The prayer book of Otto III. To the ruler as an admonition and promise into eternity . In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien Vol. 38, 2004, pp. 55–88, here: p. 76.

- ^ Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on the Ottonian Mainzer Illumination , Bonn 1987, p. 46.

- ^ Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on the Ottonian Mainzer Illumination , Bonn 1987, p. 36.

- ^ Klaus Gereon Beuckers: The Ottonian donor image. Image types, motives for action and donor status in Ottonian and early Salian donor representations In: Klaus Gereon Beuckers, Johannes Cramer, Michael Imhof (eds.): Die Ottonen. Art - Architecture - History , Petersberg 2002, pp. 63–102, here: p. 73.

- ^ Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on the Ottonian Mainzer Illumination , Bonn 1987, p. 79.

- ^ Rudolf Ferdinand Lauer: Studies on Ottonian Mainzer Illumination , Bonn 1987, p. 78.

- ^ Elisabeth Klemm: The book type. The early medieval illuminated prayer book , Lucerne 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 59.

- ↑ Ludwig Conrad Bethmann: Journey through Germany and Italy in the years 1844–1846 , in: Archive of the Society for Older German History, Vol. 9, 1847, pp. 513–515, here: p. 515.

- ^ Joseph Anton Endres, Adalbert Ebner: A royal prayer book of the eleventh century In: Festschrift for the eleven hundredth anniversary of the Campo Santo in Rome , Freiburg / Br. 1897, pp. 296-307.

- ^ Hermann Hauke: Otto III's prayer book. , Lucerne 2008, p. 42.