Villa Romana del Casale

| Villa Romana del Casale | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

|

| View from the west, in the foreground the thermal baths |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (i), (ii), (iii) |

| Reference No .: | 832 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1997 (session 21) |

The Villa Romana del Casale (Roman Villa of Casale) is a late Roman villa urbana near the town of Piazza Armerina in the free municipal consortium of Enna in Sicily . It is often referred to simply as the Villa del Casale or the Villa of Piazza Armerina . The villa is an important monument of Roman Sicily and famous for its floor mosaics. In 1997, UNESCO declared the Villa Romana del Casale a World Heritage Site .

overview

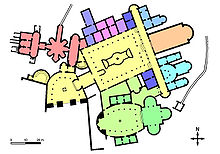

The complex of buildings of the Villa del Casale covers about 1.5 hectares. Around 45 rooms are still preserved today. The remains of the villa can be divided into four adjacent areas with different orientations:

- a monumental entrance area with three arches and a polygonal courtyard,

- a central area with a rectangular peristyle , garden and water basin, the surrounding rooms and a basilica,

- a complex with an elliptical peristyle, the surrounding spaces and a triclinium ,

- a thermal bath with access from the northeast corner of the rectangular peristyle and from the entrance area.

The floor of almost all rooms of the property is covered with mosaics of colored tesserae , which cover a total area of around 3,500 m² and consist of around 120 million individual stones, more than in any other known building of the Roman Empire. The stylistic differences between the mosaics of the different areas are very clearly visible. However, this does not indicate an execution in different epochs, but rather different workshops that used different model albums (master books ). The style of the mosaics reveals the influence of North African artists who may also have carried out the work.

Each of the four areas of the villa is on its own level due to the slope of the property and has its own directional axis. Despite the obvious asymmetry in the floor plan, the villa is the result of an organic and unified project. Based on common models of private housing at the time (villa with peristyle, hall with apses and three-aisled hall), a number of changes were introduced to give the entire complex both originality and impressive monumentality. The unity of the building fabric is also attested by the well thought-out routing and the subdivision into public and private areas. Two aqueducts from the east and north-west supplied the complex with water.

location

The villa is located five kilometers southwest of today's Piazza Armerina in the Casale district on a semicircular plateau on the left slope of a small valley below Monte Mangone , through which a tributary of the Gela flows. At the time it was built, it was six kilometers north of the Philosophiana farming settlement . The highway from Akragas (today's Agrigento ) to Catania ran 300 meters away . There was an older building at this point from which remains of thermal baths and other structures, but no mosaics, were found.

Historical background

During the first two centuries of the Roman Empire , Sicily had suffered a period of depression caused by the latifundia production system based on slave labor . City life was in decline, the land was deserted and the wealthy owners did not live on their property, as the lack of leftover homes seem to indicate. For rural Sicily, however, a new era of prosperity dawned at the beginning of the fourth century. Trading posts and peasant settlements reached their peak of expansion and activity. An obvious indication of change is the granting of a new title to the governor of the island, who instead of corrector was now called consularis .

The increasing prosperity was due on the one hand to the increasing importance of the provinces of Africa and Tripolitania for grain deliveries to Italy. As a result, Sicily played a central role on the new trade routes between the two continents. On the other hand, the wealthier classes, i.e. knights ( equites ) and senators , began to leave life in the city behind and to retreat to estates in the country. So the owners took care of their lands themselves, which were no longer cultivated by slaves but by colons . Considerable sums of money were expended to enlarge, beautify and make more comfortable the extra-urban residences or villas . Examples include the Villa del Casale, the Villa Romana del Tellaro , the Villa Romana di San Biagio and the Villa Romana di Patti .

Dating and owner

The identity of the builder and owner has long been debated and many different hypotheses have been formulated. Closely related to this is the question of dating, whereby in addition to a stylistic classification of the mosaics and other findings, especially coin and ceramic finds are of importance. A clear, precise dating is not possible, however, and the proposals extend to almost the entire 4th century AD. Traditionally, most researchers have tended to date to the first decades of the century. According to Roger JA Wilson, for example, the villa was “probably between 310 and 325 AD ". Petra C. Baum-vom Felde, on the other hand, suggested dating these works to the second half of the fourth century based on her investigations into the geometric mosaics of the villa, which Brigitte Steger, for example, joined on the basis of further analyzes. The villa itself is probably older, but in its first few decades it was much smaller and not yet decorated with mosaics. However, this late dating also has some inconsistencies and is therefore not generally recognized.

With regard to the owner, the hypothesis that had prevailed for a long time was published in 1952 by Hans Peter L'Orange and later also taken up by Josef Polzer and Gino Vinicio Gentili (1959). According to them, the owner of the villa was the Emperor Maximian (from 285 AD Caesar in the west, 286–305 Augustus ), who retired here after his abdication. A key argument in favor of this was that three of the villa's mosaics show officials with specific headgear. It is the pileus pannonicus , a special form of the pileus with which the emperors of the Tetrarchy liked to portray themselves in order to emphasize their origins in the Danube region, and which can also be seen, for example, in the Venetian tetrarch group . In the period that followed, however, historical studies showed that Maximian spent his last years in Campania and not in Sicily. In 1973, Heinz Kähler suggested that the villa could also have belonged to his son Maxentius , who ruled as emperor from 305-312 AD; Salvatore Settis (1975) and Gino Vinicio Gentili shared this view .

In the villa of Piazza Armerina, however, an imperial residence is not necessarily to be seen. In recent decades, excavations have shown that owning such impressive buildings with a representative character was nothing unique and was quite common among the Roman aristocracy. It was also emphasized that the pileus Pannonicus appears in depictions of the Illyrian emperors of the time around 300, but was ultimately simply an attribute of soldiers and military. The themes of the mosaics in the Villa Romana del Casale nevertheless point to the Roman elite of the beginning of the fourth century, to the pagan religion as well as to connections to the senatorial class and take a stand against the politics of Constantine . Therefore, since the 1980s, various high-ranking senators have been considered as clients of the villa.

One hypothesis identifies the owner with a distinguished person of the Constantinian era, Lucius Aradius Valerius Proculus , governor of Sicily from 327 and 331 and consul in 340. The games he organized in Rome in 320 while holding the praetur were so impressive that her fame went on for a long time. Perhaps the representations in some of the villa's mosaics (the “course of the great hunt” and the “circus games” in the gymnasium of the thermal baths) should remind of this event. Another suggestion holds two other governors of Sicily, Betitus Perpetuus Arzygius (presumably officiated between 312 and 324) and Domitius Latronianus (officiated 314), for the clients. It was also Caeionius Rufius Albinus proposed as owner of the villa, or at least a former prefect of Rome , about the family of Sabucii . Finally, in 2017 Brigitte Steger pleaded for the large extension of the villa, to which most of the structures and mosaics visible today, to go back, to the Sicilian governor from 364/365 and later consuls, city prefects and historians Virius Nicomachus Flavianus .

Excavations

The villa was still in use during the Byzantine rule in Sicily, as shown by restoration work on the mosaics. Then an Arab settlement emerged on the site, which was destroyed by the Normans in the second half of the 12th century. In 1761 the villa was rediscovered. When interest in old buildings reawakened in the 18th century, the ruins of the villa were initially thought to be remains from the Arab era and were called "Casale dei Saraceni". The British Consul General Robert Fagan began digging in 1808. In 1881 the first systematic excavations took place under Luigi Pappalardo, during which, for example, parts of the mosaic floor of the triclinium were exposed.

It was not until the 20th century that the entire complex was uncovered in three excavation periods. The excavation began in 1929 under Paolo Orsi after the municipality had acquired part of the site. The triclinium was excavated. After the mosaics had been photographed, Orsi had them backfilled to protect them from weathering. Further excavations took place from 1935 to 1941 under Giuseppe Cultrera after the municipality had acquired further parts of the site. They too focused on the triclinium and its surroundings. However, the mosaics were not filled in again, but preserved. In the third excavation period from 1950 to 1954 under Gino Vinicio Gentili , the remaining parts of the villa were uncovered. Other smaller excavations were carried out in 1970 under Andrea Carandini and 1983–1985. Further research excavations took place between 2004 and 2014 when the protective roofs over the exposed walls were replaced.

conservation

The mosaics are superbly preserved as they were spilled in the 12th century by landslides that caused the ceilings and part of the walls to collapse. In addition to the floors, the walls have been preserved at a height of two to eight meters. They consist entirely of bonded with mortar rubble stone , the local pieces with irregular brown rock was disguised. The mosaics are now protected by a building that mimics the ancient villa. The building is fully roofed; Visitors get access via walkways that are located on the ancient walls and from which one can look down into the rooms from above at the mosaics. In 1991, a landslide buried nearby structures; In 1995, vandals launched a paint attack.

Detailed description

Monumental entrance and vestibule

The property was accessed via a 27.75 m wide arch of honor with three passageways up to 6 m high and decorated with paintings of a military character. There are two water basins in front of the two middle pylons .

The first, horseshoe-shaped courtyard was surrounded by marble columns with Ionic capitals, and in the center are the remains of a square fountain. From the original design of the floor there is a remnant of a two-tone mosaic in a scale pattern on the northern edge. To the west of the courtyard, the lower-lying stable and a semicircular latrine can still be seen.

A few steps lead from the entrance to the vestibule : In the middle of a geometrically patterned floor there is a partially preserved arrival scene in two registers . In the upper one, a man with a crown of leaves on his head and a candlestick in his right hand, flanked by two young men with branches in their hands, seems to be waiting for the arrival of an important guest. In the lower register, some boys recite or sing with open writing boards ( diptychs ) in their hands. Scientists have seen it as a religious scene or a festive welcome for the owner to move into his home.

Rectangular peristyle

The vestibule leads to the first peristyle with columns of the Corinthian order typical of the third century . The floor mosaic shows a plait garland that divides the floor into square fields. In these, surrounded by a circular laurel garland, the animal heads of many different species can be found (big cats, antelopes, bulls, wild goats, horses, deer, wild donkeys, ibex, an elephant and an ostrich). The orientation of the heads changes in two places: Towards the entrance from the vestibule and at the feet of the access stairs to the hall with the apse on the eastern side. These changes probably had the purpose of highlighting the two routes inside the building: to the left of the entrance one got to the private rooms in the northern area and the other direction led to the hall with the apse on the eastern side and to the area of the triclinium with the oval peristyle.

Rooms on the north side of the large peristyle

Along the northern side of the peristyle there are rooms for various purposes. First three service rooms, which served as a kitchen, and behind that two more that belonged to the nearby apartment of the gentlemen. They have floors with mosaics of a geometric pattern. The design schemes can be found in the repertoire of North African mosaics: It is believed that these patterns used in the villa were developed in Rome or Italy and then reached Africa , or that they were developed by North African artists between the late second and early third centuries.

The following two rooms, which are located in this arm of the peristyle and whose walls are painted, were probably bedrooms ( cubicula ) with the associated anteroom. In one of the rooms, six pairs of people are depicted on the mosaic floor, facing each other in two registers. The interpretation is unclear: Some historians saw the episode of abduction, perhaps the here Rape of the Sabines , while others, because of the lack of representation of violence and superiority of the male characters here rather the representation of a peasant dance to mark the spring festival in honor of the goddess Ceres see . The design of the heads, the clothing and the jewelry are very detailed in accordance with the art of late antiquity. The figures are shown in frontal view, the movement is only suggested by the waving clothes. The line on which the upper figures stand should represent a shadow.

The second bedroom is decorated with a floor mosaic with fishing erotes with richly decorated boats and clothes. On their foreheads, the erotes have a V-shaped symbol of uncertain interpretation, which is found in North African mosaics of the fourth century. The erotic theme is repeated several times in the rooms of the villa, as is the motif of the country houses on the lake in the background. The Eros that empties the basket of fish and the other that threatens a fish with a trident can also be found elsewhere.

The next room, located on the north side of the peristyle, was perhaps a winter dining room ( coenatio ). This room is larger than the others, has an entrance with two pillars and contains the floor mosaic of the “little hunt”. Twelve scenes are shown in four registers:

In the top register, a hunter and his dogs are chasing a fox. Below is a sacrificial scene for Diana between two men who are carrying a wild boar tied to a pole and a third man who is carrying a goat. In the third register two men watching poultry in the branches of a tree, next to it a large scene with a banquet by the owner with his pages in the forest and a hunter threatening a hare with a venabulum (spear). Below the catch of three deer with a net and the dramatic scene of a wild boar that injured a man in a swamp. It is worth mentioning two slaves who are hidden behind a stone: one tries to hit the animal with a stone, the other holds his hand in front of his forehead in fear.

The hunt ( venatio ), as it is shown here, was certainly part of the daily life of the landlord. The sacrifice for Diana, who was responsible for a successful end to the hunt, recalls Hadrian's sacrificial scene on the Arch of Constantine . The composition of the representation is typical of late antiquity: the victim and the helpers are shown in frontal view, the branches of the trees are symmetrical on both sides of the scene and a tent ( velarium ) creates a space of respect for the main person. Their function is analogous to the ciborium of the early Christian churches. The hunting scene comes from the repertoire typical of the entire western Mediterranean region, which is neatly and symmetrically arranged around the central episodes of the sacrifice and the banquet. The composition seems to come from the North African repertoire. There are similarities to the mosaic style of the " House of Horses " in Carthage and, because of the compositional and iconographic properties, to a villa in Hippo . It is possible that the mosaic laying masters came from the Roman province of Africa , perhaps from Carthage.

The course of the great hunt

From the rear, eastern part of the peristyle , you get to the “passage of the great hunt”, 65.93 meters long and 5 meters wide, both sides of which are closed off by apses . This corridor represents a connecting and separating link between the public and the private part of the villa. It leads to the large basilica and the stately rooms. Its importance is underscored by the portico , through which one reaches the peristyle from the center, and by a slight elevation. Two steps lead from the north and south arms of the peristyle into the corridor, followed by a third to the basilica.

Contrary to its name, the theme of the floor mosaic is a major animal trapping campaign for the games in Rome: no animal is killed and the hunters only use their weapons for defense. On the basis of the different technical characteristics and the obvious breaks in the composition of the mosaic, there are seven different scenes executed by two different groups of mosaicists.

The first three scenes are executed in small (5–6 mm), very regular square stones with colored glazes. There are only a few different rocks, but about twenty-five different colors.

The remaining scenes in the southern half of the corridor are made of larger stones (6–8 mm) and are less detailed. There are several types of rock and a total of fifteen different colors.

The stylistic difference between the two parts of the hallway is quite obvious. While the figures in the southern half are dry, schematic and poor in volume, those in the northern half are plastic and lifelike in the representation of the people and animals. Possibly the southern half was the work of a more conservative workshop, faithful to the stylistic canon of the third century and the figural language of the West, while the northern half was carried out by a more progressive workshop, whose diction is more in keeping with the fourth century. Presumably these artists processed Greek or Asia Minor influences.

The first scene shows the capture of various animals, each of which appears to be depicted in a different province in Africa . Tripolitania is an exception . Soldiers, who can be recognized by their clothing in the mosaic, catch a leopard in Mauritania using a method as described in the Historia Augusta : a bait lures it into a trap. In Numidia , riders in saddles catch an antelope. In Bizacena , a wild boar is caught in a swamp that may be identified as Lacus Tritonis south of Hadrumetum .

In the second scene in a harbor in front of a luxurious building in the background, perhaps a beach villa, a rider, possibly an employee of the imperial post office, supervises the transport of a heavy load. Four men carry some animals tied up or packed in boxes on their shoulders, an overseer whips a slave and other servants drag ostriches and antelopes onto a ship. Research agrees that the port of Carthage is shown here, at the port forum of which there was an octagonal building and a temple with semicircular portico in the Antonine period, which resemble the architecture in the background of this scene.

In the third scene, which is in front of the entrance to the auditorium with the apse, you can see a piece of land between two seas. In the center, a group of three people watch animals being unloaded from two ships coming from two sides. Because of the prominent position in this group one saw the representation of the tetrarchs or Maxentius (son of the tetrarch Maximian ) with two high officials, or also a procurator ad elephantos (imperial representative for the animals in the games) with two employees. The land between the two seas is surely Italy , and it may represent Ostia, the port of Rome. The simultaneous unloading of the two ships is an example of the narrative style typical of late antiquity.

The fourth scene shows the animals being shipped in an eastern port, perhaps in Egypt , as the depictions of an elephant, a tiger and a dromedary suggest. The hunters wear trousers in an oriental style.

The fifth scene depicts the trapping of rhinos on the Nile . Typical red flowers and characteristic pagoda buildings can be seen.

The sixth scene shows in the upper part the fight between wild animals and a lion who attacks a man and is therefore killed. Below, a person of high age with an honorable and authoritarian expression, flanked by two soldiers with shields, awaits the arrival of a mysterious box that could contain the griffin depicted at the end of the corridor.

The seventh scene shows the capture of a tiger in India with a ruse handed down by Claudian and St. Ambrose . A crystal ball is thrown at the tiger. The animal sees its own reflection in the ball, thinks it sees one of its young and turns its attention away from the hunters, who can catch it without difficulty. The last episode, which has caught the attention of many researchers because of its uniqueness, shows the capture of a gryphon with a human bait.

In the apses of the north and south ends of the corridor, which served as narthices or chalcidica (waiting areas), there are two female figures. The poorly preserved northern figure holds a spear in his right hand and is flanked by a lion and a leopard. It is perhaps the personification of Mauritania , or, more broadly, Africa . The other female figure has olive-green skin. The animals around them, a small-eared elephant, a tiger and a phoenix indicate a personification of India . Formidines , red ribbons, which Indian hunters used to capture tigers, hang from the branches, which are also shown .

The depiction of a hunt or animal trapping is a relatively obvious subject for a hunting lodge and generally belongs to the typical iconographic repertoire of royal or aristocratic glorification . What makes the hunt in Piazza Armerina unique, however, is the representation of well-known areas of land from west to east, with personifications and characteristic animal species for each region. So this mosaic is read like a map . This is an imperial attribute: it was believed that the possession of maps could in a certain way increase the influence of the sovereign over those areas. In addition, one of the recurring themes of imperial glorification was the spread of imperial glory and honor to the remotest borders of the world. This explains the importance of mythical creatures such as the griffin and the phoenix as symbols of the most distant and mysterious lands. The reasons for this choice of topic could only be clarified with the secure identification of the owner of the villa.

In terms of style, the mosaic of the “great hunt” fits perfectly into the artistic environment of the fourth century. Indeed, there are a number of expressive modules found on the Arch of Constantine in Rome, such as the hairstyles of the characters, the division of the scenes into two opposite registers, the frontal representation, the two-dimensionality and the hierarchical proportions in which the narrative style the dimensions of landscape elements are reduced to a minimum. The careful decorations, the attention to detail, the lively choice of colors (in the clothes of the servants, hunters and officials, in the feathers of the ostriches) anticipate the developments in Byzantine art, in which brocade fabrics and jewelry cover the human figure. This rich decoration already conceals the fundamental loss of the sense of organic naturalism, as shown by the use of shadows that fall by chance and that certainly differ from the original models, for example in the hooves of the ox pulling the cart in the middle of the mosaic.

The Basilica

At the rear of the great hunt hallway, in the middle, is the access to a great hall with an apse, raised by four steps and highlighted by two columns .

The public function of this auditorium, in which the owner probably held an audience and received visitors, is made very clear by the special design of the floor with slabs of colored marble and porphyry. The hall is at the end of an ascending path that starts at the monumental entrance. The course of the great hunt represents a further step on the increasingly splendid way to the basilica. A comparison with similar examples, the “Villa of Portus Magnus ” in Algeria from the third century, the “ Roman Villa of Fishbourne ” in Sussex , the "Praetorium" by Lambaesis and the Constantine Basilica in Trier assigns this apparently superfluous corridor the function of a waiting room. A similar solution was found in the narthex of Christian churches in the following centuries , especially in various buildings in the Greco - Aegean region, which are dated between the end of the fourth and fifth centuries, when the narthex, connected to the eastern arm of the Atrium doubled this in length, just like the course of the great hunt at the peristyle. These similarities have led to hypothetical statements about an actual “liturgical” function of the basilica and the associated rooms, similar to the audience ceremonies of the imperial court in late antiquity.

The stately rooms in the eastern part

On the side facing the basilica, the two stately suites of rooms are located on the corridor of the great hunt. One is to the north, closer to the servants' rooms, and is smaller in size. It probably belonged to the family, i.e. the landlady or the owner's son. The other is more richly decorated and probably belonged to the owner himself.

Rooms north of the basilica

The first room functions as an anteroom. The floor is adorned with the story of Ulysses how he outsmarted Polyphemus when he handed him a wine goblet. Paintings of the same content on the Palatine Hill could indicate an imitation. In any case, it is an indication of the owner's cultural background and his ties to Rome.

A room with an apse adjoins the anteroom. Possibly it can be identified as a dining room ( triclinium ) or as a cubiculum with an alcove-shaped bed in the apse. On the walls there are representations of erotes and on the floor there is a geometric mosaic in which there are circles with allegories of the four seasons and fruit baskets. The apse is decorated with a scale-shaped motif with sophisticated and very naturalistic elements.

Another room that also leads to the anteroom is another cubiculum with an alcove. The floor is patterned with polygonal shapes, stylized stars and allegories of the seasons in circles surrounding a medallion with a couple in love. The pair of lovers represents Adonis and Aphrodite. The passage by the alcove shows scenes of children playing, while the alcove itself has a geometric decoration.

Rooms south of the basilica

These rooms lead over a forward horseshoe-shaped peristyle with Ionic columns and a fountain in the middle onto the passage of the Great Hunt. On the floor there is a mosaic with a view of the harbor, which is arranged around fishing erotes. The choice of themes is similar to that of one of the northern rooms. There is a stylistic difference between the northern and southern halves of this mosaic. In the south there are fewer trees, the sea is depicted with straight lines rather than zigzag lines and the buildings in the background can be seen from the front and are not connected to one another. Obviously different templates were used here.

At the back of the peristyle is a large apse-like room that may be the owner's library. The mosaic floor shows the poet Arion of Lesbos , who attracts sea animals, tritons and nereids with his song . In the apse the head of the Ocean is depicted, surrounded by many different fish. The helmet-like hair ornament of the Nereids gave information about the period of origin because of its similarity to the coin depictions of the empresses of the Constantinian dynasty . The arrangement and meaning of the scene are very similar to the mosaic of Orpheus in the room south of the large rectangular peristyle.

On the left side of the horseshoe-shaped peristyle there are two connected rooms, a bedroom with a rectangular alcove and an anteroom.

In the anteroom there is a mosaic of the competition between Eros and Pan , attended by boys and girls who may be relatives of the owner. On a table in the background lie crowns, the prizes for the winner. This is a rather unknown episode in mythology, but it was part of the host's culture. This theme can be found in the early Christian basilica of Aquileia , which was built around the same time.

In the bedroom there is a mosaic with hunting children. The scenes are arranged in several registers, the spaces in between are filled with sprawling branches with leaves and fruits and birds. Among the humorous scenes, that of the falling boy biting the calf by a rat and that of the boy fleeing from a rooster, a motif that can be found in medieval depictions of Arcadia .

On the opposite side there are two similar rooms, an anteroom and a bedroom with an alcove closed off by an apse.

The so-called children's circus mosaic covers the floor of the anteroom. In the arena, four carts pulled by birds and driven by children compete against each other. A child with a palm frond in hand has the task of honoring the winner. One interpretation recognizes here the allegory of the course of the four seasons. The representation of the sun and moon in chariots on the Arch of Constantine in Rome is similar .

The bedroom is decorated with an agone : children singing or reciting can be found on three registers. Here, too, as in the mosaic of Eros and Pan, the table with the victory crowns can be found in the background. In the apse, two girls weave garlands of flowers and leaves, which could refer to a spring festival in honor of Ceres .

In the mosaics of these rooms there is a synthesis of the entire iconographic program of the villa: cunning and poetry (Eros and Arion) triumph over sheer force (Pan and the sea animals); the hunting theme (the hunting children); the circus (the children on the carts); Poetry and Music (Agone, which draws on the contest between Eros and Pan and the scenes with Arion and Orpheus).

Spaces south of the rectangular peristyle

Directly adjacent to the stairs that lead to the corridor of the great hunt, there are two service rooms on the south corridor of the large peristyle, which were originally laid out with geometrically patterned mosaics. In a later construction phase, one room was equipped with a mosaic, which became known as the “mosaic of the girls in bikini ”. Ten young women can be seen playing sports on two registers.

The arrangement of the elements in the hall of Arion in the northern stately rooms is identical to that of the Orpheus mosaic in a room with an apse located behind the center of the portico. Its importance is emphasized by the entrance flanked by two pillars and the fountain in the middle of the room. Maybe it's a music room or a library. At the center of the mosaic is the mythical poet Orpheus , surrounded by more than 50 different animals, including a phoenix . There is a close conceptual connection between the scene of Arion and that of Orpheus: Both show the control of the force of nature (the sea animals and the wild beasts) through poetry and song, i.e. with the spirit. This theme is also taken up in the depiction of the victory of Odysseus over Polyphemus by List in the vestibule of the northern apartment. In the mentality of the time, musicality was part of wisdom, and wild animals were often a metaphor for human passions, for example with Lactantius .

The elliptical peristyle with the triclinium

From the corridor of the great hunt, from the stately rooms and from the south-eastern part of the great peristyle, one arrives at a single complex consisting of an oval peristyle with columns ( xystus ) and a large room with three apses ( trichora ). On both sides of the peristyle there are three small rooms, of which the middle one is accessible from the peristyle. On the remaining side there is an apse with a fountain ( nymphaeum ).

The arcade of the peristyle is covered with a mosaic with acanthus garlands in which there are animal busts. The side rooms are decorated with mosaics of erotes who fish in the southern rooms and who are busy harvesting grapes in the north: in front of a country house, two erotes carry baskets full of grapes to two others who have prepared the wine press.

The floor of the next side room is covered with a mosaic with tendrils, grapes and erotes; in the center there is a medallion with a male bust, perhaps representing the personification of autumn. This mosaic is very similar to a mosaic made only a few years later in the mausoleum of Constantina in Rome. This depiction, which also adorns the porphyry sarcophagus of Constantina, was very common in the eastern Mediterranean, where it can be found in Jordanian churches until the late sixth century .

The room with the three apses was a banquet hall ( coenatio ) for the winter. The entrance with granite columns is accessible from the peristyle via four steps. The mosaic in the middle of the room is not completely preserved, it shows the deeds of Hercules . In the north apse the hero is taken into Olympus, in the south the transformation of the nymph Ambrosia into a vine and in the east the fight of Hercules against the giants.

Between the central mosaic and the apses there are scenes from the Metamorphoses , namely the transformation of Daphne into a laurel tree, Cyparissus into a cypress and Andromeda and Endymion into stars.

The complex of representations refers to the heroic apotheosis of the demigod . This is a motif often used in imperial propaganda as an allusion to the divinity of the emperor.

The thermal baths

Directly from the monumental entrance of the villa one arrives at a thermal bath complex , which could also be visited by non-residents and which was built over an older bathhouse, which explains its asymmetrical orientation. The access from the courtyard to the palaestra was through two vestibules with geometric mosaics.

Another access from the western corner of the large peristyle was reserved for the residents of the villa. This asymmetrical room is furnished with a bench built along the walls and probably served as a changing room. The floor mosaic shows the lady of the house with two children and two servants. From here you can also get to the Palaestra (15 × 6 m), which ends in two apses and is decorated with a circus mosaic. The Circus Maximus in Rome is shown in great detail , in which a race with four quadriga takes place, in which the green party ( Prasina ) wins.

This is followed by the frigidarium , on the wall of which there are six niches, two of which serve as entrances. In the south there is a small rectangular room with three small apses and in the north a swimming pool, also with an apse. The mosaic of the central room again shows a scene with fishing erots, nereids , tritons and seahorses, the representation of which adapts to the octagonal shape of the room. In the niches, which perhaps served as changing rooms, people are depicted who, supported by slaves, are getting dressed and undressed. The walls were covered with marble.

This is followed by a small room with a mosaic depicting a massage, from which one enters an oblong room with apses, which must have been the tepidarium , in which there is a poorly preserved mosaic depicting athletes. One of the ends of the room leads into three heated rooms, the caldariums .

literature

- Petra C. Baum-vom Felde: The geometric mosaics of the villa at Piazza Armerina. Kovač, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0940-2 .

- Andrea Carandini, Andreina Ricci, Mariette de Vos: Filosofiana. The villa of Piazza Armerina. The image of a Roman aristocrat at the time of Constantine. Palermo 1982.

- Luciano Catullo: The ancient Roman villa of the hamlet of Piazza Armerina in the past and present. Morgantina . Arione, Messina 1999 (large format).

- Gino Vinicio Gentili: Piazza Armerina . In: Richard Stillwell et al. a. (Ed.): The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1976, ISBN 0-691-03542-3 .

- Biagio Pace: I mosaici di Piazza Armerina. Gherardo Casini Editore, Rome 1955.

- Umberto Pappalardo, Rosaria Ciardiello: The splendor of Roman mosaics. The Villa Romana del Casale near Piazza Armerina in Sicily. Philipp von Zabern (Scientific Book Society), Darmstadt 2018, ISBN 978-3-8053-4880-5 .

- Salvatore Settis : Per l'interpretazione di Piazza Armerina. In: Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome. Antiquité. Volume 87, Number 2, 1975, pp. 873-994 ( online ).

- Brigitte Steger: Piazza Armerina. La villa romaine du Casale en Sicile (= Antiqva. Volume 17). Picard, Paris 2017, ISBN 978-2-708-41026-8 ( detailed scientific review ).

- Roger JA Wilson: Piazza Armerina. Granada, London 1983, ISBN 0-246-11396-0 .

- Roger JA Wilson: Piazza Armerina. In: Terakazu Akiyama (ed.): The Dictionary of Art . Volume 24: Pandolfini to Pitti. Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-517068-7 .

Web links

- Official site (in Italian) with a map

- Side of the UNESCO (in English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Roger JA Wilson: Piazza Armerina. In: Akiyama, Terakazu (ed.): The dictionary of Art. Volume 24: Pandolfini to Pitti. Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-517068-7 .

- ↑ a b c d e Luciano Catullo: The ancient Roman villa of the hamlet of Piazza Armerina in the past and present . Arione, Messina 1999.

- ↑ Petra C. Baum-vom Felde: The geometric mosaics of the villa at Piazza Armerina. Kovač, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-8300-0940-2 , pp. 419-449.

- ^ Brigitte Steger: Piazza Armerina. La villa romaine du Casale en Sicile. Picard, Paris 2017, ISBN 978-2-708-41026-8 , pp. 46–58.

- ↑ See, among others, Roger JA Wilson: Review of “Brigitte Steger: Piazza Armerina. La villa romaine du Casale en Sicile. Paris 2017 “ BMCR 2020-03-17, accessed April 11, 2020.

- ^ Hans Peter L'Orange: È un palazzo di Massimiano Erculeo che gli scavi di Piazza Armerina portano alla luce? In: Symbolae Osloenses. Volume 29, 1952, pp. 114-128.

- ↑ Heinz Kähler: The Villa of Maxentius near Piazza Armerina (= Monumenta Artis Romanae. Volume 12). Mann brothers, Berlin 1973.

- ↑ Andrea Carandini, Andreina Ricci, Mariette de Vos: Filosofiana. La Villa di Piazza Armerina. Immagine di un aristocratico romano al tempo di Costantino. Flaccovio, Palermo 1982.

- ^ Giacomo Manganaro Perrone: Note storiche e epigrafiche per la villa (praetorium) del Casale di Piazza Armerina. In: Sicilia Antiqua. Volume 2, 2005, pp. 173-191. On terms of office, see Arnold Hugh Martin Jones , John Robert Martindale, John Morris : Fasti. In: The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire (PLRE). Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1971, ISBN 0-521-07233-6 , p. 1096.

- ↑ Salvatore Calderone: Contesto storico, committenza e cronologia. In: Giovanni Rizza (Ed.): La Villa Romana del Casale di Piazza Armerina. Atti della IV Riunione Scientifica della Scuola di Perfezionamento in Archeologia Classica dell'Università di Catania (Piazza Armerina, September 28th - October 1st, 1983). Università di Catania, Istituto di Archeologia, Catania 1988, pp. 45-57.

- ↑ Patrizio Pensabene: Risultati complessivi degli studi e degli scavi 2004–2014. In: Derselbe, Paolo Barresi (ed.): Piazza Armerina, Villa del Casale: scavi e studi nel decennio 2004–2014. 2 volumes, “L'Erma” di Bretschneider, Rome 2019, pp. 711–761, here p. 713 and p. 730.

- ^ Brigitte Steger: Piazza Armerina. La villa romaine du Casale en Sicile. Picard, Paris 2017, ISBN 978-2-708-41026-8 , pp. 58-73.

- ↑ Carmine Ampolo include: La Villa del Casale a Piazza Armerina. Problemi, saggi stratigrafici ed altre ricerche. In: Mélanges de l'école française de Rome. Volume 83, Number 1, 1971, pp. 141-281 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Patrizio Pensabene, Paolo Barresi (ed.): Piazza Armerina, Villa del Casale: scavi e studi nel decennio 2004–2014. 2 volumes (= Bibliotheca archeologica. Volume 60). “L'Erma” di Bretschneider, Rome 2019.

- ^ Salvatore Settis: Per l'interpretazione di Piazza Armerina. In: Mélanges de l'Ecole française de Rome. Antiquité. 87, 2, 1975, pp. 873–994, here, pp. 903–905 Fig. 19 (PDF)

- ↑ P. Baum-vom Felde: On the interpretation of a geometrical-figurative mosaic floor of the late Roman villa near Piazza Armerina. In: Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 31/2, 2005, pp. 67-105.

Coordinates: 37 ° 21 ′ 53 ″ N , 14 ° 20 ′ 5 ″ E