Ban on images in Islam

The ban on images in Islam (especially in Sunni Islam) is the result of a controversial discussion in traditional Islamic literature and jurisprudence about the legitimacy of images of people and animals, both in the secular and in the religious field. The Arabic term for pictorial representations is Arabic صورة ، صور sura, pl. suwar , DMG ṣūra, pl. ṣuwar 'picture, drawing, figure, statue', and Arabic تمثال, تماثيل timthal, Pl. tamathil , DMG timṯāl, Pl. tamāṯīl 'pictorial representation, statue', the latter mostly three-dimensional.

The Koran and pictorial representations

The Koran does not contain a ban on images . In some verses of the Qur'an, Allah is portrayed as the greatest sculptor and creator: Sura 3 , verse 6; Sura 7 , verse 11; Sura 40 , verse 67. In Sura 59 , verse 24 he is praised as “the creator, creator and designer”. In the Koran exegesis , the above Koran passages are not associated with a ban on images, it is about divine attributes ( ṣifāt Allāh ) and almighty creative power.

In this context, also in Islamic theological literature, sura 5 , verse 90 and sura 6 , verse 74 are also cited , which, however, are obviously not directed against images as such, but rather against their worship and thus against polytheism and idolatry . The effectiveness of and compliance with the Islamic ban on images are still there to the present day, but are generally more derived from the traditional collections than from the Book of Revelation. “Especially in the sacred area, i. H. In the mosques and in the Koran manuscripts there are hardly any pictures of living beings. "

Bishr Farès finally pointed out that the Islamic scholar al-Qurtubī , for example, claimed in his Qur'an commentary Tafsīr Aḥkām al-Qur habeān that the prohibition on the production of images was based on individual Koranic stories such as the one according to which Solomon made images of the jinn and Jesus formed doves out of clay in order to then bring them to life, has not been undisputed.

Image hostility and prohibition in the hadith literature

The first written evidence against pictorial representations is only in the hadith literature in the late 8th century, in the Muwaṭṭaʾ al-Muwatta ' /الموطأof Mālik ibn Anas verifiable. When Umm Habiba and Umm Salama - two wives of Muhammad - reported about the Māriya Church in Abyssinia and the images there to the Prophet shortly before his death, he is said to have replied, according to tradition:

“If a pious man dies among them, they build a place of prayer over his grave and put these images in it. Such people are the worst creatures before God on the day of resurrection. "

With the emergence of the canonical collections of hadiths , the authors of which died between 870 and 915, further sayings of Muhammad came into circulation that expressed his personal aversion to pictorial representations. In the four books of the Shiites there are also traditions hostile to images. A precisely described and required punishment for the production and use of pictorial representations in this world is not handed down in the hadith either; the hell punishment threatened only in the afterlife is intended to deter people from producing pictures and sculptures and from owning them. The German orientalist Rudi Paret has compiled some hadiths with similar content that is hostile to images and in a study devoted to this question presented the possible origins of the discussions about the prohibition of images among Islamic scholars. On the basis of the canonical collections of traditions, he compiles fourteen variants of tradition, which more or less speak in favor of a ban on images and which document the discussions about them.

In the chronological classification of the hadith materials, the accompanying circumstances described there result in some historically usable fixed points that are important in the dating questions of the discussions. The following hadith qudsi is updated during the visit to the house of Marwan ibn al-Hakam , in which images were placed. Thereupon the companion of the prophet Abū Huraira († 679) quoted the saying:

"And who is more outrageous than whoever prepares to create as I [God] create ..."

This view, according to which such a creative power is peculiar to God alone, is documented several times in Islamic literature; it is based on the Koran, in which God speaks to Jesus:

"And (at that time) when you, with my permission, created something out of clay that looked like birds, and blew into them so that, with my permission, they were (after all real) birds ..."

The house of Marwan - from 662 to 669 and from 674 to 677 governor of Medina - is well-known and its building history is documented in literature. Another tradition leads to the same time:

“Those who make these images will be punished on the day of the resurrection. One will say to them: 'Bring to life what you have created!' ... "

This saying is said to have caused the early Koran exegist Mujāhid ibn Jabr († 722) to even declare the pictorial representation of fruit-bearing trees to be reprehensible and to justify his view with the above hadith qudsi : "And who is more outrageous than whoever prepares to to create as I (God) create ... "

Another tradition, which is passed down several times in the canonical collections of traditions, is related to the above hadith:

“He who takes a picture will be required on the day of resurrection to breathe life breath (rūḥ) into him. But he won't be able to do that. "

The Melchite theologian Theodor Abū Qurra († around 820) quotes this saying almost literally.

All in all, the hadiths discussed by Paret thus offer clues for starting the discussions about the ban in the last decades of the 7th and beginning of the 8th century. This, however, "does not stand in the way of the fact that details of the implementing provisions were only discussed and decided in later legal literature, such as the question of the degree to which the image of a living being is no longer destroyed by the prohibition." KAC Creswell and Oleg Grabar , however, did not begin the discussion about a ban on images until the late second half of the 8th century.

Historical documentation

According to older sources, the famous historian at-Tabarī , whose work falls into the late 9th century, reports that after the Arab conquest of Ctesiphon (al-Mada'in), the general Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas moved into the abandoned, magnificent palace of Sassanid ruler (Kisra) entered and expressed his admiration for the colonnade by reciting a passage from the Koran ( Sura 44 , verse 25-26).

“Then he said the morning prayer there, not the communal prayer, but instead prayed eight body bows ( rukūʿ ) one after the other. He made the place (thus) a place of prayer, in which plaster figures, foot soldiers and riders were. Neither he nor the (other) Muslims took offense, they left (the characters) as they were. Sa'd completed the prayer on the day he entered the (city), wanting to reside there. The first Friday prayer that was performed in Iraq for all (Muslims) was in Ctesiphon in the safari of the year 16 (March 637). "

According to this report, there was no ban on images at the time of the first conquests. Because not even the narrators of this event seem to have taken offense at the fact that their ancestors created an Islamic place of prayer out of a place with images. The aversion to pictorial representations, which can only be proven later, is not documented among the first Umayyads ; under the caliph Mu'awiya I - ruled between 661 and 680 - portraits of rulers can be found on Arabic coins. It was only with the coin reform in the first half of the 8th century that an attitude hostile to images gradually took hold. While the last Umayyad coin - under Sassanid influence - with the image of the caliph Abd al-Malik dates from the year 703, the coins of the following period only bear Arabic inscriptions.

The pictorial representation of people took place primarily in two phases of Islamic history: while the first includes the Umayyad and early Abbasid rule between the 7th and 10th centuries, the second began under the Fatimids in 10/11. Century and reached its climax in the illumination of the late 12th and 13th centuries in Islamic Mesopotamia .

The initiative to build the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem also goes back to 'Abd al-Malik, the interior of which is characterized by rich climbing elements and mosaics based on the Byzantine model.

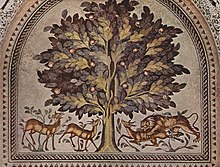

His successors Hisham and al-Walid II ruled between 724 and 744 and were the builders of the magnificent Khirbat al-Mafjar خربة المفجر / Ḫirbatu ʾl-mafǧar - called “Hisham Palace” - near Jericho , a desert palace which, with its lavish representations in mosaics and sculptures, is one of the most beautiful witnesses of Islamic architecture from the first half of the 8th century. Many of the sculptures, the caliph, half-naked women, hunting scenes, all under Byzantine - or Nabatean - influence, and parts of the Musallā place of prayer المصلى / al-muṣallā are on display today in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. Another example is Qusair 'Amra with his frescoes of unclothed women from the same period. Al-Hakam II. ( D. 976) had in Madinat az-zahra' مدينة الزهراء / madīnatu ʾz-zahrāʾ near Córdoba set up a fountain decorated with human figures.

In the interior of the Ka'ba there were also sculptures that the Meccan scholar 'Ata' ibn Abi Rabah, who died in 736, had seen himself: the figures of Jesus and Mary are not until 692, during the fire of the Ka'ba under the “Counter-caliph” Abdallah ibn az-Zubair , was destroyed.

The edict of the Umayyad caliph Yazid ibn 'Abd al-Malik on the destruction of images in Christian churches on his national territory in the year 721 or 722 is to be seen in connection with the Byzantine iconoclasm that sparked at that time .

Islamic jurisprudence

Since neither the Koran nor the Hadith literature provide clear evidence for a ban on images in Islam, Islamic jurisprudence ( fiqh ) was required to make legally binding regulations on this issue. Islamic legal scholars hold three, sometimes controversial, views on the visual representation of humans and animals:

- Representations are not forbidden, haram , unless they are used as objects of religious worship - next to the only God. The representation of God is of course taboo, the description of his attributes and his essence in theological writings is not the subject of jurisprudence.

- Depiction of objects that “cast shadows”, ie sculptures, is prohibited, drawings of the same on paper, walls, in textiles are not prohibited, but reprehensible ( makruh ). If people or animals are headless or not completely depicted in other respects, but cast shadows, they are allowed. The shadow theater widespread in the Orient and North Africa is legalized under Islamic law, as the characters are perforated and therefore cannot have a “soul” (peace).

- the representation of living beings, humans and animals, is prohibited in every respect.

All three directions can cite from the hadith literature corresponding statements traced back to Mohammed as the basis of argumentation for their teaching.

Several hadiths, both sayings of the prophets and statements of the companions of the prophets , relate to the chess game schatrandsch /شطرنج / šaṭranǧ apart. The ban on the game of chess is justified because it uses pieces that cast shadows and because the game (lahw) itself distracts from prayer. On the other hand, the shadow play that emerged at the time of Saladin is tolerated, as the figures are “perforated” ( muṯaqqab ) and are therefore not living beings.

Another object the representation of which is prohibited in Islam is the cross (salib)صليب / ṣalīb , the symbol of the Christians. It is not only the symbol of the rum, the Byzantines , the enemies of Islam, but is destroyed on the day of the resurrection of Isa bin Maryam himself - at least that is what several hadiths traced back to the prophet in the canonical collections of traditions say . According to other traditions, the prophet is said to have had the cross in his surroundings and the patterns of the same removed from clothing, which was probably brought to the Arabs by Christian traders.

The same state of mind is expressed in a hadith obtained from Ahmad ibn Hanbal , in which Muhammad is made to speak as follows:

"God has sent me as grace and guidance to humanity and commanded me to destroy the wind and string instruments, the idols, the cross and the Jahiliyya customs."

Even in the oldest writings of Islamic jurisprudence, the public setting up of the cross by the non-Muslim population living under Islamic rule in the areas where Muslims settled is sharia law.

Like pictorial representations of people, animals and objects that “cast shadows”, the Muslim may not make a cross, order its production or trade with it.

In general it can be stated that the pictorial representation in art and architecture is avoided the more

- the building or work of art is closer to the religious area (e.g. the mosque and its inventory),

- The environment (client, artist, ruler) in which a building or work of art is created is more strictly religious,

- more people can access the area in which a building or work of art is located.

One can assume “that the prohibition of images, which theologians have handed down, formulated legally and within certain limits also monitored, was observed above all in sacred art: particularly, of course, in mosques, but also in other public buildings Gravestones and, as far as book art is concerned, in Koran manuscripts. ”However, this applies with restrictions. Several images have been preserved in a copy of the Koran acquired in Istanbul in 1930. The unknown copyist who made the book in 1816 was a student of a certain Dāmād ʿUṯmān ʿAfīf Zādeh († 1804). The black and white drawings were added to the Quran text later and depict episodes from the life of Muhammad among his companions .

Numerous examples in Islamic art show that there can be no question of an absolute ban on images in Islam: representative rooms, palaces and baths are just as inconceivable in secular construction as they are in edifying literature ( adab ), e.g. B. in the Makamen of al-Hariri , or in the fable Kalīla wa Dimna . The representation of living beings is also common in medical and scientific works from the Arab-Islamic cultural area.

Islamic images of Muhammad

The portrayal of the prophet is assessed differently in the Islamic cultural area. In connection with the great importance of the word , as it were as a carrier of revelation, the avoidance of pictorial representations leads to a dominant role of writing (calligraphy) and ornament in Islamic art. The writing itself often becomes an ornament, or ornaments are designed in a manner similar to writing.

Images of Muhammad are therefore rare; they are found mainly as illumination in Persian and Ottoman manuscripts. Images of this kind first appeared from the second half of the 13th century in the empire of the Mongolian Ilkhan who converted to Islam . Muhammad's night journey was a particularly popular motif. Initially, the pictures showed a representation of Muhammad's face, often surrounded by a halo or a flaming aureole; From the 16th century onwards there was a move to hide his face behind a veil out of piety or to depict Muhammad only as a flame. The illuminations were not part of public life, but were used for the private edification of rulers and wealthy patrons who had these pictures made for themselves. In Iran , on the other hand, you can find popular pictures of Mohammed today, which are sold as postcards or posters.

Islamic iconoclasm

In history there have been numerous iconoclastic destruction of images from other cultures and religions by Muslims; The Buddhist , Hindu and Jain sites in northern India have suffered a great deal (see e.g. Quwwat-ul-Islam-Mosque in Delhi ).

Recent examples are:

- the destruction of the Buddha statues of Bamiyan and of frescoes and other exhibits of the Buddhist religion in the museum in Kabul by Islamist- motivated terrorist attacks by the Taliban in 2001

- the attacks by Taliban militias with explosives in northwestern Pakistan on Buddha statues of the Gandhara culture that are thousands of years old , among others at Manglore and Jehanabad in 2007

- the destruction of Assyrian and Parthian sculptures by terrorists assigned to the so-called Islamic State in the Museum of Mosul in 2015

- the destruction of the archaeological sites of Nimrud in 2015

- the demolition of the most important ancient ruins of Palmyra by terrorists in 2015

- the destruction of the Islamic cultural heritage in Saudi Arabia

See also

literature

- Rudi Paret : The Islamic Ban on Images and the Schia , in: Erwin Gräf (ed.), Festschrift Werner Caskel , Leiden 1968, pp. 224–232

- Rudi Paret: Text documents on the Islamic ban on images . In: The artist's work. Studies offered to H. Schrade. Stuttgart 1960, pp. 36-48

- Rudi Paret: The Islamic ban on images . In: J. Iten-Maritz (ed.): The Orient Carpet Seminar . No. 8 (1975).

- Rudi Paret: The emergence of the Islamic ban on images. In: Art of the Orient. Vol. XI, 1/2 (1976-1977). Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden. Pp. 158-181

- KAC Creswell: Lawfulness of Painting in Early Islam . In: Ars Islamica, Vol. 11-12 (1946), pp. 159-66.

- E. García Gómez: Anales palatinos del califa de Córdoba al-Hakam II , por ʿĪsā ibn Aḥmad al-Rāzī. Madrid 1967

- Ignaz Goldziher : On the Islamic ban on images. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG), 74 (1920), p. 288

- Wilhelm Hoenerbach : The North African shadow theater . Mainz 1959

- Snouck Hurgronje: Kissjr 'Amra and the ban on images . In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG) vol. 61 (1907) p. 186 ff.

- Mohsen Mirhmedi: Prolegomena to a systematic theology of the Koran. Dissertation, Free University of Berlin, 2000. Chap. 4: On the relationship between ethics and representation - the ban on images. Pp. 74-106 ( online ).

- Nimet Şeker: Photography in the Ottoman Empire , Würzburg 2010.

- AA Vasiliev: The Iconoclastic Edict of the Caliph Yazid II. AD 721 . In: Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Nos. 9 and 10 (1955-1956), pp. 23-47

- Reinhard Wieber: The game of chess in Arabic literature from the beginning to the second half of the 16th century. Walldorf-Hessen 1972 (contributions to the linguistic and cultural history of the Orient, 22). Diss. Bonn 1972

- The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition , Brill, Leiden: Vol. 8, p. 889 ( ṣūra ); Vol. 10. P. 361 ( taṣwīr )

- Silvia Naef: Images and ban on images in Islam , CH Beck, Munich, 2007

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christoph Sydow: Myth of ban on images

- ↑ “It is He who forms you in the wombs as He wills. There is no god but Him, the mighty, the wise. "(Translation by Max Henning)

- ↑ “And verily, We created you; then We formed you; [...] "(translation by Max Henning)

- ↑ “It is He who created you out of dust, then out of a drop of seed, then out of clotted blood, then He lets you emerge as little children. [...] "(translation by Max Henning)

- ↑ “O you who believe, behold, the wine, the game , the images, and the arrows [used in drawing lots] are an abomination of Satan's work. Avoid them; maybe you are doing well. "(translation by Max Henning)

- ↑ “And (remember) when Abraham said to his father Azar: 'Do you accept images of gods? See, I see you and your people in an obvious error. '"(Translation by Max Henning)

- ^ Oleg Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art , Yale University Press, New Haven, 1987, p. 79.

- ↑ Rudi Paret: Symbolism of Islam. In: Ferdinand Herrmann (Ed.): Symbolism of Religions . Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1958, p. 13.

- ^ Bishr Farès, Philosophy et jurisprudence illustrées par les Arabes , in: Mélanges Louis Massignon , Volume 2, Damascus: Institut Français de Damas, 1957, pp. 101ff.

- ↑ Rudi Paret: The emergence of the Islamic ban on images . In: Art of the Orient, XI 1/2 (1976–1977), p. 162. Franz Steiner Verlag. Wiesbaden; In the Muwatta 'review by Abū Muṣʿab, Vol. 2. No. 1974. 2. Edition. Beirut 1993.

- ↑ Rudi Paret, The Islamic Ban on Images and the Schia , in: Erwin Gräf (Ed.), Festschrift Werner Caskel. Dedicated to his seventieth birthday on March 5, 1966 by friends and students , Brill, Leiden, 1968.

- ↑ The Islamic ban on images and the Shia . Pp. 224-238. Addenda to this in: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG), Vol. 120 (1970), pp. 271-273.

- ↑ Rudi Paret: The emergence of the Islamic ban on images. In: Art of the Orient. Vol. XI, 1/2 (1976-1977). Franz Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden. Pp. 158-181

- ↑ Ignaz Goldziher: On the Islamic ban on images. In: Journal of the German Oriental Society (ZDMG), Volume 74 (1920), p. 288 ( online )

- ↑ Rudi Paret, op. Cit. 165 and note 7

- ↑ Rudi Paret, op. Cit. 166-167; on the hadith see ibid. p. 162

- ↑ Ignaz Goldziher (1920), p. 288 after Ahmad ibn Hanbal , Mālik ibn Anas u. a.

- ↑ Rudi Paret, op. Cit. 162 and note 4

- ↑ a b Rudi Paret, op. Cit. 177

- ↑ KAC Creswell, The Lawfulness of Painting in Early Islam , in: Ars Islamica , Vol. 11-12 (1946), pp. 160f.

- ↑ Oleg Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art , p. 83.

- ↑ Koran, Sura 44, verses 25-26: "How many gardens and springs did they leave, 26 And fields of seed and noble places." (Translation by Max Henning)

- ↑ Rudi Paret: “The Islamic Ban on Images”. In: J. Iten-Maritz (ed.): The Orient Carpet Seminar . No. 8 (1975).

- ↑ Philip Grierson : "The Monetary Reform of 'Abd al-Malik". In: Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (JESHO), 3 (1960), pp. 241-264; esp. 243 and 246.

- ^ Eva Baer: The human figure in early islamic art: some preliminary remarks. In: Muqarnas 16 (1999), p. 32

- ^ Myriam Rosen-Ayalon: The Early Islamic Monuments of the al-Haram al-Sharif . An Iconographic Study. Qedem. Monographs of the Institute of Archaelogogy. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. 28 (1989). Bes. Color Plates I – XVI. without images of humans or animals.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 5 p. 10.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 1, p. 608; Eva Baer: The human figure in early islamic art: some preliminary remarks. In: Muqarnas 16 (1999), pp. 33-34

- ↑ See: E. García Gómez (1967) - Index.

- ↑ About him see in detail: Harald Motzki: The beginnings of Islamic jurisprudence . Their development in Mecca up to the middle of the 2nd / 8th centuries Century. Treatises for the Customer of the Orient (AKM), Vol. L, 2. Stuttgart 1991. pp. 70ff

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 9, p. 889; according to the city history of Mecca by al-Azraqī (d. 865)

- ^ AA Vasiliev: The Iconoclastic Edict of the Caliph Yazid II. AD 721 . In: Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Nos. 9 and 10 (1955-1956), pp. 23-47; The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 9, p. 889; Rudi Paret (1975)

- ↑ See: al-mausūʿa al-fiqhiyya . Kuwait 2004 (4th edition), vol. 12, p. 92ff; The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, suffering. Vol. 8, p. 889 (ṣūra); Vol. 10, p. 361 (taṣwīr).

- ↑ See: al-mausūʿa al-fiqhiyya . Kuwait 2004. Vol. 35, pp. 269-271; R. Wieber, Das Schachspiel ... , p. 48 ff.

- ↑ See: CF Seybold: On the Arabic shadow play . In: Journal of the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (ZDMG), 56 (1902), pp. 413-414

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Brill, Leiden, Vol. 8, p. 980 with reference to the collection of al-Bukhari and Ahmad ibn Hanbal

- ↑ See: al-mausūʿa al-fiqhiyya . Kuwait 2004. Vol. 12, p. 88.

- ^ E. Fagnan: Le livre de l'impôt foncier . Paris 1921, pp. 218-19; d. i. the French translation of the Kitab al-Kharaj by Abu Yusuf .

- ↑ al-mausūʿa al-fiqhiyya . Kuwait (4th edition), 2004, vol. 12, pp. 88 and 91.

- ↑ Rudi Paret (1975), p. 3.

- ^ Richard Gottheil: An Illustrated Copy of the Koran. Paris. Libr. Orientaliste Paul Geuthner 1931. From: Revue des Études Islamiques (1931)

- ↑ a b c Carl W. Ernst: Mohammed consequences: Islam in the modern world . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, September 11, 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-54124-1 , pp. 104, 215 (accessed on December 3, 2011).

- ↑ Kees Wagtendonk: Images in Islam . In: Dirk van der Plas (ed.): Effigies dei: essays on the history of religions . BRILL, 1987, ISBN 978-90-04-08655-5 , pp. 120-124 (accessed December 1, 2011).

- ↑ a b c d Freek L. Bakker: The challenge of the silver screen: an analysis of the cinematic portraits of Jesus, Rama, Buddha and Muhammad . BRILL, September 15, 2009, ISBN 978-90-04-16861-9 , pp. 207-209 (accessed December 1, 2011).

- ↑ FE Peters : Jesus and Muhammad: Parallel Tracks, Parallel Lives . Oxford University Press, November 10, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-974746-7 , pp. 159-161 (accessed December 1, 2011).

- ^ Christiane Gruber: Representations of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting . In: Gülru Necipoğlu (ed.): Muqarnas . BRILL, October 31, 2009, ISBN 978-90-04-17589-1 , p. 253 (accessed December 3, 2011).

- ↑ Contemporary reports on temple destruction under the Mughal ruler Aurangzeb