Maximilian III Joseph

Maximilian III Joseph Karl Johann Leopold Ferdinand Nepomuk Alexander of Bavaria , Max III for short . Joseph (born March 28, 1727 in Munich , † December 30, 1777 ibid), from the Wittelsbach family, was elector of Bavaria from 1745 until his death. Since Bavaria proved to be too weak for a great power policy in the style of its predecessors, the elector concluded a separate peace with Austria's Archduchess Maria Theresa soon after he came to power and orientated himself towards Habsburg in foreign policy . In the Seven Years' War , in which Bavaria was allied with Austria and France , he tried to get out of the conflict as soon as possible and made a significant contribution to the declaration of neutrality of the Holy Roman Empire . As a result - because of his childlessness - his main focus was on clarifying the succession in spa Bavaria and the Electoral Palatinate .

In terms of domestic policy, it was necessary to reduce the country's immense debt burden. He carried out limited administrative reform. The codification of Bavarian law was more important. He also pursued a policy of economic development and state development . As an absolutist ruler, he tried to limit the influence of the estates and to place the church under the influence of the state as much as possible. Under his reign compulsory schooling was introduced and the elector proved to be a patron of art and science. After his death the Bavarian War of Succession broke out.

family

Max III. Joseph was the son of Emperor Charles VII and Maria Amalies of Austria , the daughter of Emperor Joseph I. On the occasion of his birth, the Annenkirchen in Munich received special support from his father, and the foundation stone for the monastery church of St. Anna im Lehel was laid .

He himself married Princess Maria Anna of Saxony , daughter of King August III , on July 9, 1747 in Munich . of Poland and his wife Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria . The marriage remained childless.

Early years

From 1742 he experienced formative youth in Frankfurt am Main at his father's imperial court , which after the loss of Bavaria resembled an exile . The Jesuit Daniel Stadler and the constitutional law teacher Johann Adam von Ickstatt had a major influence on his upbringing . Stadler remained his confessor and advisor for many years. Ickstatt also continued to exert a great influence on the elector. Max III. Joseph studied at the University of Ingolstadt .

On the day of his death, January 20, 1745, by virtue of imperial authority, his father declared Max III, who was not yet 18 years old. Joseph came of age, which meant that he could take the throne as Bavarian Elector without a guardian and spa administrator . Duke Clemens Franz or Max Joseph's later father-in-law, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland August III., Would have been possible guardians .

Elector of Bavaria

Foreign policy

After the father's death in the middle of the War of the Austrian Succession , the Munich court first tried to continue the anti-Habsburg and pro-French great power politics. One even thought of Max III. To have Joseph succeed his father as emperor. Of his father's conference ministers, Törring and Preysing and, half-heartedly, Fürstenberg, spoke out in favor of it, while Königsfeld and Praidlohn advised caution. However, France's willingness to support Bavarian politics was also much less than initially assumed. The Empress-Widow, Count Seckendorff and almost all the higher military and civil servants pushed for peace with Austria.

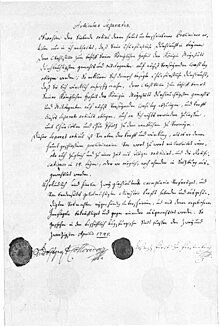

After troops of the Habsburg Monarchy attacked Bavaria on March 23, 1745, occupied parts of northern Bavaria in a coup d'état and caused the Bavarian allies a loss-making defeat in the Battle of Pfaffenhofen on April 15, the elector had to accept the hopelessness of his ambitions and closed on April 22 Maria Theresa the Peace of Füssen . In doing so, he renounced the previous great power policy and promised to elect Franz Stephan of Lorraine for the emperor election . For this, he was confirmed to have full ownership of Bavaria. The payment of 40,000 guilders to Bavaria within two weeks, which was agreed in a secret clause, alleviated the Electorate's acute financial distress for the time being. Until the election of the new emperor, Elector Maximilian III. Joseph, after consultation with Karl Theodor von der Pfalz, became the imperial vicariate from February 1745 . The vicariate coins minted in Munich show the bust of the elector and the double-headed eagle with the Bavarian coat of arms on the reverse.

After France failed to provide funding, Bavaria was dependent on subsidies from Austria, Great Britain and the Netherlands . At the mediation of Maria Theresa, it therefore concluded ten-year subsidy agreements with the sea powers in 1746. In terms of foreign policy, this forced it entirely on the side of Austria and its allies. Bavaria had to provide an auxiliary corps, which was deployed in the Netherlands until the Peace of Aachen in 1748.

From 1754 Bavaria pursued a policy of rapprochement with France under the ministers Preysing and Seinsheim , which led to the Compiègne Treaty in 1756 after the expiry of the treaties with Great Britain and the Netherlands . In it, Bavaria pledged itself against subsidies of 300,000 guilders annually not to provide the Reich with any troops against France and to strive for the neutrality of the Reich in the event of a war between France and Austria. The newly gained foreign policy room for maneuver was lost in the same year as a result of the Renversement des alliances with the merger of Austria and France. In view of the financial situation and a weak army, an independent foreign policy was hardly conceivable.

Max III. Joseph acted cautiously on the side of France and Austria during the Seven Years' War . A lasting weakening of Prussia was not in the Bavarian interest, as this country offered the only counterweight to the Habsburg monarchy. He tried as much as possible to stay out of the war. Apart from the Circle troops , he put only a small force of 4,000 men. The Elector brought the auxiliary force back in 1758/1759 and tried to get out of the conflict. Together with Karl Theodor von der Pfalz, he contributed to the fact that the empire declared itself neutral. However, this only succeeded when France and Great Britain made peace with one another. When the war in 1759 made it dangerous for Max Joseph's brother-in-law, the Elector of Saxony Friedrich Christian, to stay in Dresden again , he fled with his family to Munich, where he was hospitable and stayed for two years. In relation to Prussia, Max III declared. Joseph declared himself neutral in 1762 and in February 1763 the empire also decided to be neutral towards both warring sides. This was one of the factors that led to the Peace of Hubertusburg . A clear turn against Austria was not connected with this. The elector even married his sister Maria Josepha to Joseph II in 1765. When Emperor Franz I Stephans died in 1765, his son Joseph II was already German king, so there was no further vicariate of the elector. Due to the early death of Maria Josepha in 1767, the marriage did not have any direct political effects, but it strengthened the potential inheritance claim of Habsburg in the event of the Wittelsbach spa line becoming extinct.

After it was clear that he and his wife would have no heirs, the regulation of the succession in favor of the Palatinate line of the Wittelsbach family became the main task of the elector. Through the house contract of Pavia , the Wittelsbach family split in 1329 into an older Palatinate and a younger Bavarian line. Finally, it was possible to move all lines of the Wittelsbach house to a common agreement. On September 22, 1766, the Electors Max III signed. Joseph and Karl Theodor initiated a renewal of the hereditary brotherhood, in which Bavaria and the Palatinate were treated as an indivisible joint property for the first time. In 1771 it was agreed that Bavaria and the Palatinate as a whole should fall to the respective head of one of the surviving lines.

Domestic politics

Especially after the end of the Seven Years' War he devoted his attention to the internal consolidation of Bavaria. Maximilian Franz Joseph von Berchem became the first minister . As an enlightened prince, Max III stayed. Still caught up in a patrimonial understanding of the state, he viewed the state as his private property. An urgently needed reform of the state administration was therefore not carried out.

The elector tried, however, to improve the state apparatus. In 1750 a court council order was issued and the secret conference was reintroduced in 1764. With the creation of the foreign department under Berchem, a step towards a specialist ministry was taken. However, there was no comprehensive administrative reform. The consequent step towards ministerial departments or even the post of leading minister was not taken. Although the elector listened to advisers, he basically clung to the prince's direct rule.

The legal codification of both civil and criminal law under the direction of Council Chancellor Wiguläus von Kreittmayr was of great importance . For this reform, too, the main motive was the hoped-for cost savings through shorter procedures and greater legal certainty. With the Codex Maximilianeus Bavaricus Criminalis , Bavaria got a formally groundbreaking penal code, which was divided into a general and a special part and in which elementary criminal law terms such as attempt , aiding and abetting and complicity were defined with previously unknown clarity. In terms of content, however, the Codex was backward-looking and thus contrasted with the cautious modernization of criminal law in Prussia and Austria, inspired by the ideas of the Enlightenment . The torture was not abolished, nor crimes such as witchcraft and heresy . The death penalty , which varied depending on the offense, continued to include the particularly cruel execution methods of burning alive and wheeling .

In view of the poor financial situation of the country, the main focus was on economical housekeeping and the promotion of the economy. For example, the deer hunting park was closed as early as 1745 and Max III founded it in 1747. Joseph founded the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory , which soon became world famous thanks to Franz Anton Bustelli . In 1755, in the imperial city of Buchhorn, a transshipment point for the export of salt to Switzerland was found. The numerous other measures to renovate the household include the establishment of a faience factory in Friedberg Castle in 1754 and the construction of a silk filatorium (textile factory) at the Munich court garden in 1762 by Lespilliez . Not all projects showed sustainable success. In addition, there was a well-planned population policy, which included a ban on emigration, which was only relaxed for the poor even in the economic crisis of the 1770s, and a policy of land development . For example, previously unusable bog areas were drained. In order to better plan government activities, a land survey was carried out in 1752/60 . The Dachsberg folk description began in 1771 . This was the first time that systematic population and trade statistics were produced for Bavaria. When a bad harvest caused a great famine in 1770, the elector had grain distributed from farm estates to alleviate the hardship, took out loans in Holland and even sold some of the jewels in the treasury. With the support of the estates, the elector succeeded in at least partially paying off the immense national debt and in consolidating the state finances. Max Joseph could not profit financially from the death of his uncle, the Cologne elector Clemens August von Bayern , he was defeated in 1767 in an inheritance dispute before the Imperial Court of Justice . Nevertheless, the elector was able to reduce Bavaria's debt burden by half in the course of his government.

Max III. As an absolutist prince, Joseph was opposed to the traditional class privileges. This attitude was also evident towards the Catholic Church . He was personally pious and around 1747 had the Oberammergau Passion Play forbidden by his clergyman on the grounds that “the greatest secret of our holy religion does not belong on the stage”. His piety did not prevent him from placing the church under state influence as far as possible. The church council was expanded in 1768 to an administration of state church sovereignty. In addition, the elector endeavored to tax church property. The Jesuit order was repealed in 1773 .

In 1748 he restricted the rights of cities and markets. He also endeavored to at least economically integrate the imperial cities of Regensburg and Augsburg . The elector was in a permanent conflict with the landscape ordinance as a representative of the estates. Advised by his former teacher Ickstatt, he tried twice in vain to remove this body. The resistance was so great that Ickstatt even had to leave the farm at times. A main reason for failure was that Max III. Joseph was financially dependent on the estates. At the end of his rule, a representative new building for the state estates , the New Landscape Building in Munich, was built.

Promoter of the arts and sciences

Max III. Joseph was a friend of the arts and a patron of the sciences. However, in contrast to his predecessors, he was no longer able to finance large new construction projects due to the mountain of debt caused by them. Essentially, he had to limit himself to restoring or completing older buildings. In this context, the Cuvilliés Theater was a rococo masterpiece . He also commissioned François de Cuvilliés with the “Stone Hall” in the main building of Nymphenburg Palace , which was completed in 1756, and in 1768 with the completion of the facade of the Theatine Church . Some rooms in Schleißheim Palace were also redesigned. For the residence in the capital, only the electoral rooms of Johann Baptist Gunetzrhainer were built in a modest way for the time. A new wing planned by Cuvilliés on the east side of the residence, which has been unsightly since the demolition of the remaining parts of the Neuveste, was not realized due to a lack of funds. The general mandate of the Elector of October 4, 1770, in which he practically forbids the Rococo as a “ridiculous” ornament for country churches and demands a “noble simplicity” is famous.

Max III. Joseph was regarded as a man who enjoyed celebrating, loved going to the opera, was enthusiastic about the theater and hunting. For Max Joseph's limited resources, the fact that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's employment was rejected by the Elector, who himself was musical and composed, was rejected for reasons of cost. Mozart's work La finta giardiniera was only premiered in the Salvatortheater in Munich . However, Max Joseph's influential director Seeau was not hired for Mozart either.

The founding of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts and the Bavarian Academy of Sciences were of lasting importance . He thereby contributed to the fact that the education in Bavaria gained in importance. Although Max Joseph, composed of enlightened educational reformer Heinrich Braun , the compulsory education had prescribed in the Electorate of Bavaria already in 1771, a six-year legal compulsory education could be enforced only 1,802th

Like all Wittelsbachers, the young Max Joseph had to complete a technical apprenticeship as well as a scientific apprenticeship - he decided on an apprenticeship as a turner and devoted himself particularly to ivory , some of his work being preserved in the castles. Max Joseph's wood turning cabinet can still be seen in Nymphenburg Palace today .

Death and succession

Due to the lack of male descendants, the rule of the Bavarian Wittelsbach family was drawing to a close and the succession became the subject of general attention in European diplomacy. The Bavarian Prince Clemens died in 1770 , so apart from the Elector there were no more male Wittelsbachers from the Bavarian line. Numerous princes had previously occupied ecclesiastical bishoprics and thus could not produce any legitimate heirs. Max Joseph's food was tried by a taster with every course - the elector was too afraid of being poisoned.

At the beginning of December 1777 the elector fell ill without initially worrying the court and its foreign diplomats. His personal physician Sänftl initially treated the disease as measles . Elector Max III died at the end of December. Joseph the "beloved" after three weeks of suffering from smallpox . He had always refused a smallpox vaccination for himself, which he had prescribed for his subjects. His death was received with sadness and consternation by the population. Max Joseph was buried in the Theatine Church in Munich. His heart was buried separately and is located in the Chapel of Grace in Altötting .

For Emperor Joseph II, who looked at the Bavarian legacy, the death of Max Joseph at this point was probably rather inconvenient:

"[...] I receive the news that the Elector of Bavaria played the trick on us to die."

he wrote to his Minister Kaunitz . With Max Joseph, the Bavarian line of the Wittelsbach family died out in the male line. Now, with Karl Theodor, the Palatinate line of the Wittelsbach family succeeded him. The agreements of the house union had designated Munich as the residence, at the same time the Palatinate electoral dignity was extinguished and the Bavarian one remained in accordance with the provisions of the Peace of Westphalia. Karl Theodor had no internal relationship with Bavaria and was willing to swap it first partially for the front of Austria and later entirely for the Austrian Netherlands . After a short War of the Bavarian Succession , which cost Bavaria the Innviertel , Karl Theodor continued to try to swap Bavaria for areas close to his native Rhenish lands. The widow of Max Joseph and Clemens, Maria Anna of Saxony and Maria Anna von Pfalz-Sulzbach , saw threatening the Bavarian independence had, however, with Frederick II. Of Prussia and Karl Theodor heir Charles II. August von Pfalz-Zweibrücken in touch and the Prussian king threatened both Bavaria and Austria with war if Karl Theodor's plan was carried out. Emperor Joseph II shied away from another war with Prussia and finally abandoned his plans for good in 1785, after Friedrich had brought the Prince League into being that year .

Awards (selection)

- House Knight Order of Saint George (Bavaria) (Grand Master)

- Order of the Golden Fleece (Knight)

Pedigree

| Pedigree of Elector Maximilian III. from Bavaria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great-great-grandparents |

Elector |

Duke |

Jakub Sobieski (1590–1646) |

Henri de la Grange d'Arquien (1613–1707) |

Emperor Ferdinand III. (1608–1657) |

Elector Philipp Wilhelm of the Palatinate (1615–1690) |

Georg Fürst von Calenberg (1582–1641) |

Eduard von der Pfalz (1625–1663) |

| Great grandparents |

Elector |

King |

Emperor Leopold I (1640–1705) |

Johann Friedrich Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1625–1679) |

||||

| Grandparents |

Elector Maximilian II. Emanuel of Bavaria (1662–1726) |

Emperor Joseph I (1678–1711) |

||||||

| parents |

Emperor Charles VII (1697–1745) |

|||||||

|

Elector Maximilian III. |

||||||||

literature

- Karl Theodor von Heigel : Maximilian III. Joseph . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 21, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1885, pp. 27-30.

- Alois Schmid : Maximilian III. Joseph. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 485-487 ( digitized version ).

- Alois Schmid: Reform absolutism, Elector Max III. Joseph , in: Journal for Bavarian State History 54, 1991, 39–76.

- Andreas Kraus : History of Bavaria: from the beginning to the present. Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09398-1 , pp. 353-363.

Web links

- Literature by and about Maximilian III. Joseph in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Maximilian III. Joseph in the German Digital Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alois Schmid: Max III. Joseph and the European Powers. The foreign policy of the Electorate of Bavaria from 1745–1765 . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-53631-1 , p. 151 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Schmid: Max III. Joseph . Munich 1987, p. 34 f . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Schmid: Max III. Joseph . Munich 1987, p. 150 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Schmid: Max III. Joseph . Munich 1987, p. 78 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Max Spindler: Handbook of Bavarian History . Ed .: Andreas Kraus. 2nd revised edition. tape 2 . Old Bavaria. The territorial state from the end of the 12th century to the end of the 18th century. Beck, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-406-32320-0 , p. 1200 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ A b Sebastian Frank: 1756 VII 21 Compiègne neutrality and subsidy agreement. (No longer available online.) In: European peace treaties of the premodern online. Leibniz Institute for European History Mainz, formerly the original ; Retrieved September 23, 2013 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Schmid: Max III. Joseph . Munich 1987, p. 311 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Spindler: Handbook of Bavarian History . Munich 1988, p. 1203 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hans Rall: Kreittmayr. Personality, work and continuation . In: Journal for Bavarian State History (ZBLG) . No. 42 . Beck, Munich 1979, p. 51 ( digitized version [accessed September 29, 2013]).

- ^ Rall: Kreittmayr . Munich 1979, p. 50 ( digital-sammlungen.de ).

- ^ Rall: Kreittmayr . Munich 1979, p. 52 ( Digitale-sammlungen.de ).

- ↑ Winfried Müller: Max III. Joseph . In: Alois Schmid and Katharina Weigand (eds.): The rulers of Bavaria . 25 historical portraits of Tassilo III. until Ludwig III. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-48230-9 , pp. 273 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ http://www.sueddeutscher-barock.ch/ Nymphenburg Palace

- ↑ Friedrich Weissensteiner: The great rulers of the House of Habsburg (2016)

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Karl I. Albrecht |

1745–1777 |

Charles II. Theodore |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Maximilian III Joseph |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Elector of Bavaria (1745–1777) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 28, 1727 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Munich |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 30, 1777 |

| Place of death | Munich |