History of Naples

The Italian city of Naples has a long and eventful, to a substantial extent from foreign domination and oppression embossed history to look back. In the buildings and museums , but also in the cultural peculiarities of the city, traces from almost all periods of this long development can be found to this day.

antiquity

Italians

Before the founding of the Greek colonies , the Campania region was populated by Italian peoples: the Oscans , Samnites and the immigrant Etruscans .

Greeks (700 BC-326 BC)

- Pithekoussai and Cumae

The first Greek settlement in Campania emerged from 770 BC. On the island of Ischia . The name of the city was Pithekoussai , but it is still not clear whether it was the first Greek colony or just a city with a Greek trading base. The Greeks who lived in Pithekoussai came from the Greek island of Evia , just like the founders of the first polis on the Italian mainland. Around 740 BC. The influential Greek colony Cumae was founded here.

- Parthenope (or Paleopolis )

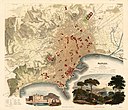

Around 700 BC BC the Greeks from Cumae founded another settlement, namely Parthenope (later also Paleopolis , i.e. "old city") in what is now the city of Naples. Parthenope was on the seaside hill Pizzofalcone (also called Monte Ecchia ) and the small island of Megaride adjoining it . The Port of Parthenope was in the northwest of the city.

- Neapolis

Since about 500 BC A second city began to emerge in the northeast of the port of Parthenope. From then on, the city of Parthenope also bears the name Paleopolis , which means something like "old city". The second city, in the area of today's old town, was named Neapolis , the "new city".

Only remnants of the city wall and a few other functional structures have been discovered on buildings from the Greek period. Remains of the Greek city wall can still be seen in Piazza Bellini today. Like many other Greek colonies, Neapolis was built according to a grid-shaped plan that goes back to the city planner Hippodamos . Today's city lies above the Greek one, but the streets of the old town still follow the same course as they did then. Three main streets (the Plateiai , in Roman times: Decumani ) crossed the Greek city from west to east and were connected by many small alleys (the Stenopoi , Latin: Cardi ). The main square of the Greek city, the Agora , was located on today's Piazza San Gaetano, the fortress ( Acropolis ) on the Caponapoli hill in the north-western corner of the Greek city.

The city soon became one of the most prosperous Greek cities in southern Italy (→ Magna Graecia ). An with the expanding Rome 326 BC The treaty of alliance concluded in the 3rd century BC contributed to a long relative independence. But in the Roman civil wars (88-82 BC) Naples was on the wrong side and was subsequently incorporated under Sulla as a dependent provincial city of the Roman Empire.

The Etruscans in Central Italy around 500 BC Chr.

Where the Piazza San Gaetano is today, the Greek agora and the Roman forum used to be

Excavations under the Chiesa di Sant'Agnello Maggiore , where the Acropolis of Naples was located

Romans (326 BC-476)

In the 4th century BC Naples began to become a city of the Italians , although the Greeks stayed and continued to form an influential ethnic group. Around the birth of Christ, Strabon describes Naples as a Campanian-Greek city that still had many institutions of a polis (Strab. Geograph. 5,4,7), and when Emperor Nero visited the place, he spoke Greek to the inhabitants ( Suetonius , Nero 20.2f.). Inscriptions prove that Greek remained the official language for a long time, even in Roman times; Latin only began to gain acceptance in the 2nd century AD. In 241 BC However, the independent coinage of the city stopped, which can be seen as a sign that the city had lost influence compared to other cities.

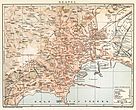

The main Roman square ( forum ) was located where today's Piazza San Gaetano is . Around this forum there was the Temple of the Dioscuri, two of the original columns of which are integrated into the current facade of the Basilica di San Paolo Maggiore , and the Roman market ( Macellum ), the remains of which can be seen under the church of San Lorenzo Maggiore . In the north of the forum, remains of the Roman theater of Naples found under residential buildings are accessible. Right next to this larger theater was a smaller, covered theater ( Odeon ). In the west of Naples, along the Posillipo hill , only tiny remnants of luxury villas of the upper class were built.

Like the Christians in the capital of the empire, the early Christian community of Naples was exposed to sporadic persecution. As in Rome, the early Christians in Naples retreated in catacombs like the hypogea on Via dei Cristallini , which the community used as a burial place and place of remembrance (but not as a place of refuge, as was previously believed). This state of affairs only finally changed when the young faith advanced from the persecuted religion to the state cult following the Edict of Tolerance in Milan . The catacombs have been preserved to this day and can be visited.

After Jordanes (Getica, 156), the Goths of Alaric moved through Campania and Lucania, i.e. to 410, and after the renewed sacking of Rome by the Vandals, these also moved through Campania after 455, as Paul Diaconus reports. However, they did not plunder Naples, but Capua and Nola (Hist. Rom. 14, 16-17). According to Paulus Deacon, they were unable to conquer Naples because of the strong walls, but they deported numerous residents of the surrounding area.

Ancient thermal baths in the Museo dell'Opera di Santa Chiara

Odoacer (476–493) and the Ostrogoths (493 – approx. 542)

After 476 the military leader Odoacer ruled Italy first, and in 493 Theodoric the Great then established Ostrogothic rule over the rump of Western Rome.

Byzantines (c. 542–763)

From 535 onwards, under the general Belisarius, the Eastern Romans temporarily conquered all of Italy on behalf of Emperor Justinian in the course of the Renovatio imperii - the attempt to restore the Roman Empire. Naples, the majority of which sided with the Ostrogoths , fell after a hard battle when Belisarius men penetrated the city through the aqueducts . With the Eastern Roman rule, the Greek language spread again in southern Italy and Sicily (until the 11th century).

middle Ages

Duchy of Naples (763–1139)

When the Lombards invaded Italy soon after Justinian's death in 568 and thus heralded the beginning of the Middle Ages, the Eastern Romans and Byzantines nevertheless managed to maintain their influence in Naples for a long time. Only in connection with the iconoclasm of the 8th century did the city change fronts and move closer to the Roman Catholic Church, which was allied with the Lombards . As a result, the Neapolitan duchy, which had already emerged in the 7th century, gained a certain autonomy, but still formally belonged to Byzantium.

In a more regional conflict (with Benevento ) the dukes of Naples called the Sicilian Arabs to the mainland around 835. The alliance lasted half a century, and Naples became a starting point for the spread of Islam in Italy and its cultural influences, which the sensitive observer can still perceive in the south of the country. Overall, the last century and a half of the first millennium were marked by continued prosperity for the city, together with the fleets of the Maritime Republic of Amalfi and the Duchy of Gaeta , which were allied at times , Naples dominated the sea trade in the Mediterranean before the Venetians and Genoese .

Normans (1139–1197)

In 1139, after tough resistance, Naples fell into the hands of the Normans and became part of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily . The Normans knew how to merge the different, Eastern Roman-Byzantine, Arab and Western roots of the region into a unique and independent cultural conglomerate through a skilful domestic policy.

Staufer (1197-1266)

The Norman rule lasted 55 years. In 1194 the Hohenstaufen came under Heinrich VI. in their place by taking advantage of a dynastic weakness of the Normans and seizing southern Italy in a short campaign. Heinrich's son and successor Friedrich II founded the University of Naples , which bears his name today, the first state university in Europe.

Anjou (1266–1442)

The Hohenstaufen rule in Naples did not last long after Frederick's death (1250). Charles I of Anjou conquered the so-called " Kingdom of the Two Sicilies " as a fief of the Pope after his coronation in Rome in 1266. After bitter disputes with the Hohenstaufen heirs, Konradin , the last male Hohenstaufen, was beheaded in Naples in 1268.

After the island of Sicily was lost to the Anjou in the aftermath of the Sicilian Vespers in 1282, they concentrated entirely on their continental possessions and made Naples the residence of their kingdom. Even if their rule, which lasted until 1442, was marked by brutal repression in domestic politics, they ensured an economic and cultural heyday of the city and took fundamental urban planning measures to modernize it. During this period, Naples, along with Florence, became the leading center in the fields of business, science, art and architecture in Italy and Europe. Numerous buildings erected under the Anjou still bear witness to the economic prosperity and cultural splendor of the city at that time.

Modern times

Aragonese (1442–1501)

In 1442 the Aragonese king Alfonso defeated the last ruler of the Anjou. Under the Aragonese, the economic ties between Naples and the Iberian Peninsula were intensified, the economy as a whole promoted and the city became a center of the Italian Renaissance .

Spanish Habsburgs (1501–1647 and 1648–1713)

At the beginning of the 16th century, after only a short episode of French rule, the city and kingdom of Naples were annexed as a province to the Spanish- Habsburg Empire. This marked the beginning of the era of the Spanish viceroys of Naples , under which the city should reach the lowest point of its economic and political development.

In just 100 years, the city's population had grown from around 40,000 in 1450 to around 210,000 in 1550, and Naples was the largest city in Italy and after Paris, ahead of Venice (160,000 inhabitants) and Milan (70,000 inhabitants) second largest metropolis in Europe. One of the few capable viceroys, Pedro Álvarez de Toledo , succeeded in his tenure between 1532 and 1553 to some extent to master this demographic problem by implementing appropriate urban development measures. He had the existing building stock increased and a new city quarter ( Quartieri Spagnoli ) built west of the Via Toledo named after him . However, these measures could only be implemented through tough tax and repressive domestic policies. It was de Toledo who introduced the Spanish Inquisition in Naples.

Moreover, the time of the viceroys was marked by an increasing intensification of class antagonisms. The main focus of the Spanish crown was on the Iberian heartland and the colonies. The few investments that were made in the city benefited only the haves, the urban nobility, the clergy and the Spanish officials, while the common population became increasingly impoverished. Nowhere in western Europe at that time were the social differences more pronounced than in Naples.

Republic of Naples (1647-1648)

After there had been a first revolt at the time of the Toledo in 1547 and subsequent unrest, the social tensions finally erupted in the Masaniello uprising of 1647, which led to the first short-lived Neapolitan republic in 1647/48.

Due to the balance of power, Spanish rule was naturally soon restored, and after another minor rebellion in 1649, the Neapolitans surrendered to their fate. In addition to all of this, the city was hit by the devastating " Great Plague " in 1656 , which killed around half of the 300,000 inhabitants. Mass graves were no longer sufficient, the victims were burned in large "purgatory".

Austrian Habsburgs (1713–1734)

The Spanish Habsburgs were replaced by the Austrian Habsburgs in 1713, which changed little for the Neapolitans.

Bourbons (1734–1799 and 1799–1806)

A clear improvement in the situation did not occur until the Bourbons , who had acquired the Spanish throne as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1712, also took over southern Italy from the Austrians in 1735. Under Charles VII , who ruled the newly formed Kingdom of the Two Sicilies from 1735 to 1759 and then from 1759 to 1788 as Charles III. in Spain, an effective reform policy was launched. Charles VII, a representative of the Enlightenment , cleared the ranks of the corrupt and decadent nobles and ecclesiastical dignitaries, made structural changes in the cityscape and promoted cultural life. His son and successor Ferdinand IV (with interruptions 1759-1825), however, lagged significantly behind his father's format, so that the city soon returned to the old conditions before the events emanating from France should shake Europe and thus also Naples.

Parthenopean Republic (1799)

At the beginning of 1799, French revolutionary troops moved into Naples under General Jean-Étienne Championnet ; the king had fled to Palermo beforehand. Neapolitan patriots then proclaimed the Parthenopean Republic , which, however, met with little approval from large sections of the uneducated population. With their resistance and the intervention of the English under Horatio Nelson , the republican experiment ended again in the same year. The Bourbone returned to Naples, and the Republicans were followed by cruel persecution, which killed almost the entire intellectual elite of Naples.

Bonapartists (1806-1815)

In the winter of 1805/06 Ferdinand IV was ousted by Napoleon Bonaparte , who first installed his brother Joseph (1806-1808) and then his brother-in-law Joachim Murat (1808-1815) as kings of Naples. The latter in particular initiated extensive social reforms and quickly became very popular with the local population.

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (1816–1860)

With the fall of Napoleon, however, the episode soon ended. Ferdinand returned to Naples and implemented a consistent policy of restoration that also removed the last traces of French reform efforts. The Neapolitans, however, who had briefly benefited from the reforms and now suffered the restorative policies of the Bourbons, began to make friends with the ideas of the Risorgimento from northern Italy for the creation of an independent Italy.

Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946)

On September 7, 1860, after the conquest of southern Italy , Giuseppe Garibaldi entered Naples to the cheering of the population, and on October 21, 1860, the Neapolitans voted in a plebiscite with an overwhelming majority for annexation to the Kingdom of Italy . Francis II , the last Bourbon ruler, had fled the city to the fortress of Gaeta , announced his surrender on February 13, 1861 and was declared deposed. On March 17, 1861, the United Kingdom of Italy was officially proclaimed a constitutional monarchy .

Many Neapolitans, however, identified only to a very limited extent with the new Italian state. State authority - regardless of who exercised it - was essentially a synonym for oppression and foreign rule for many southern Italians. The south, the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, was economically significantly underdeveloped compared to the former northern Italian states - mainly due to centuries of mismanagement by the rulers. Many development projects and funding measures of the new central government benefited mainly the north of the country, while the south was rather neglected and economically heavily burdened by an unjust and tough tax policy. Necessary reforms to eliminate the problems established during the Bourbon rule (e.g. land reform) did not take place. The government had only achieved a formal, political agreement in the country, but failed in the task of unifying the country internally. The backwardness of the south was in a way cemented. The north prospered economically in the first decades after the founding of the kingdom and soon caught up with the leading European industrial nations, while the south remained in poverty and agony. This is one of the reasons for the formation of the north-south divide in Italy, which is still in effect today. Naples, too, developed into a typical Mezzogiorno city , characterized by poverty, crime, the shadow economy and mafia-like structures that extend into the highest political and economic centers of power.

In 1884, as a result of the disastrous infrastructural and hygienic conditions, Naples fell victim to a devastating cholera epidemic. Emergency measures initiated in Rome in 1885 to rehabilitate the slums remained obsolete. An industrialization that began at the beginning of the 20th century with quasi-planned economy methods was almost inevitably doomed to failure due to poor planning, a lack of infrastructure and money seeping into dark sources and did not lead to any improvement in the economic situation. This led to the first major waves of emigration to northern Italy, Argentina and, above all, the USA.

In this situation, fascism found significantly more supporters in southern Italy than in the north of the country. In 1922, shortly before the march on Rome , a large fascist congress was held in Naples. After Mussolini came to power , the problems in southern Italy were initially overlaid, concealed and pushed into the background by the imperial aspirations of the fascists and later by the Second World War . During the Second World War, the city was repeatedly the target of heavy Allied bombing raids . These 105 attacks resulted in around 1,000 civilian deaths, even though the population sought protection in the underground cistern system of Naples. Many art-historically valuable buildings, including a number of churches, were destroyed or badly damaged. After Mussolini's deposition and arrest on July 25, 1943, Naples was occupied by Wehrmacht troops and the Neapolitans were briefly exposed to the German terror regime. In tough partisan battles by the Resistance , the city managed to free itself on its own ( four days from Naples ) before the arrival of the Allies on October 1, 1943, and to drive the occupiers out of the city.

The ensuing American occupation provided the city with a brief period of relative prosperity. The needs of the GI and the abundance of dollars were the ideal breeding ground for Naples' underground economy. The Camorra regained strength.

Republic of Italy

In the referendum of 1946 on the future form of government, the inhabitants of Naples, in contrast to the majority of the country, voted to retain the monarchy. During the subsequent constitution of the Italian republic , Enrico de Nicola, a Neapolitan, was elected its first president.

In the first decades of the young republic, nothing essential changed for the Neapolitans about the precarious conditions in the city. This led to further large waves of emigration. Between 1950 and 1970 alone, around 800,000 people left the city and the province. Once again, northern Italy and the USA, but also the Federal Republic of Germany as a flourishing economic wonderland, were the preferred destinations of the emigrants.

The government in Rome directed billions in subsidies into the region via the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno ("Treasury for the South"), which was founded to build the south, but billions in subsidies also seeped away in dark channels or were due to recent bad planning, which the existing ignored economic and infrastructural conditions, literally squandered. In the first four and a half decades of its post-war history, Naples experienced an unprecedented amalgamation of economy, politics and Camorra for Europe in the second half of the 20th century, and the city's name became synonymous with corruption, building speculation and illegal enrichment. The protagonist of this policy was the long-time mayor of the city, Achille Lauro , in Naples in particular in the 1950s . Having come into possession of a naval and financial empire through dubious methods, he used the position of mayor primarily to further expand his economic and political power. Nevertheless, as a typical populist with a pronounced Panem-et-Circenes policy , he was very popular with the population.

The compulsory deposition of Lauros by decree of the central Roman government did not change anything fundamental about the Neapolitan conditions. His successors were almost exclusively of a similar streak, whether they were Christian Democrats or Socialists. It was only in the framework of the general Italian renewal process from 1992 onwards that the situation in Naples also changed, and the era of corrupt local politicians came to an end. In 1993 Antonio Bassolino was elected mayor by the center-left alliance L'Ulivo against Alessandra Mussolini ( Alternativa Sociale ). In his term of office, which lasted until 2001, the city experienced a rapid and never thought possible upswing. Corruption was systematically fought, the influence of the Camorra at least curbed. Restoration work on the cityscape and redevelopment measures have been initiated. In 1994, Naples was the venue for the G7 summit , and in 1995 the centro storico (old town) was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO . When he was re-elected in 1997, Bassolino received 73% of the vote, and in 2000 he also became President of the Campania Region. Since 2001 his party colleague and successor Rosa Russo Iervolino has continued the local politics he started. Recently, however, the problems in Naples began to worsen again. In May 2011, Luigi de Magistris ran as the top candidate of a left-wing liberal party alliance for local elections in Naples. He surprisingly relegated Mario Morcone, the representative of the Partito Democratico of Mayor Rosa Russo Iervolino (who was no longer up for election), to third place and thus moved into the runoff election for mayor against Giovanni Lettieri, the candidate of the center-right Alliance, in which he prevailed with 65 to 35 percent. On July 18, 2011, he then resigned his mandate as a MEP.

See also

literature

- Giuseppe Galasso: Napoli capitale. Identità politica e identità cittadina. Studi e ricerche 1266-1860. Naples 1998

- Christoff Neumeister : The Gulf of Naples in antiquity. A literary travel guide. Munich 2005

- Dieter Richter : Naples - biography of a city. Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-8031-2509-X

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Christoph Höcker: Gulf of Naples . DuMont, Cologne 1999, p. 81

- ^ Christoph Höcker: Gulf of Naples . DuMont, Cologne 1999, p. 81.

- ^ Christoph Höcker: Gulf of Naples . DuMont, Cologne 1999, p. 81

- ↑ "... egressi per Campaniam et Lucaniam simili clade peracta ..."

- ↑ “Relicta itaque urbe per Campaniam sese Wandali Maurique effundentes cuncta ferro flammisque consumunt, quicquid superesse potest diripiunt, captam nobilissimam ciuitatem Capuam, ad solum usque deiciunt captiuant praedantur. Nolam nihilo minus urbem ditissimam aliasque quam plures pari ruina prosternunt. "

- ↑ On Pedro Álvarez de Toledo ( Memento of the original of May 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ About the bombing of Naples ( Memento of the original from June 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Materials on resistance under the German occupation on the partigiani.de page .

- ^ List of the Neapolitan mayors from 1900 to 1997 on the interviu.it page

- ↑ De Magistris batte Lettieri 2 a 1. Retrieved May 30, 2011 .