History of printing

The beginnings of the history of printing can be found in East Asia , Babylon and Rome . The oldest printed books have been in block printing method produced completely in which each individual page in a printing block cut from wood and was then peeled off. It is not yet the book form as we know it today. The printing press , with all its economic, cultural and scientific historical implications developed in the form known today as a cultural formative information and communication technology in Europe. With the further development of Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century , the art of book printing spread throughout Europe in just a few decades and throughout the world in the centuries thereafter.

It is said that movable type made of metal and wood were widespread in large parts of Asia, but printing with movable type, as it was later developed in Germany, could not establish itself in China. This also means that the effects of wood type and block printing in China cannot be compared with those of letterpress printing in Europe: The printing process in Asia did not allow mass printing like the one invented by Gutenberg.

However, the interplay between the production of paper, which began in East Asia more than a thousand years earlier, and that of printing plates or letters centuries before Gutenberg, “meant that by the beginning of the 19th century there were more printed Chinese pages than in any other language the world together. "

Antiquity to the Middle Ages

Antiquity

The principle of printing, insofar as it is only understood to mean the embossing of characters for a communication or recording of facts, can be traced back to the early days. In the tombs of Thebes and Babylon are bricks have been found embossed with inscriptions; Fired clay cylinders completely covered with characters by means of engraved shapes represented the place of the chronicles for the ancient Assyrians . In Athens , maps were engraved in thin copper plates. Roman potters stamped the dishes they made with the names of the orderers or with the indication of the purpose for which they were intended. Wealthy Romans gave their children alphabets made of ivory or metal to help them learn to read. And a saying by Cicero relates to these carved individual letters and how they can be put together , which in clear terms contains the principle of the type set. Another millennium and a half passed before it was actually invented. In ancient times (outside of China) there was not only a lack of paper . The requirements of the educated and learned could be satisfied by the art of copying, which was especially cultivated by the Romans and especially practiced by slaves .

China

Book printing, which, according to Stanislas Julien ( Documents sur l'art d'imprimerie ) , is said to have been invented by the Chinese as early as 581 AD , is not book printing in our sense, but a forerunner, wood panel printing . According to Chinese sources, Julien explains that in 593 the ruling emperor Wen Di ordered all unpublished writings to be collected, cut in wood and published.

The earliest example of a block print on paper was discovered in 1974 during an excavation in what is now Xi'an , the capital of Chang'an from the Tang dynasty. It is a Dharani Sutra printed on hemp paper , which is dated between 650 and 670. A Lotus Sutra that was printed between 690 and 699 was also recovered.

The oldest Chinese block print dated with a colophon is a printed version of the Diamond Sutra found in Dunhuang . The pages glued together in a roll are dated 868. This distinguishes the document owned by the British Museum from older Chinese, Korean and Japanese block prints, which are dated from the age of stone or wooden pagodas in which they were kept.

The East Asia Department of the Bavarian State Library purchased a copy of the Baoqieyintuoluojing 宝 箧 印 陀罗尼 经 in the 1980s, 84,000 of which were in the bricks used to build the famous Leifeng Pagoda in 975 on the West Lake near Hangzhou. The Buddhist texts became visible when the temple collapsed in 1924. The paper roll had already been mounted on silk before it was purchased.

A work by Shen Kuo refers to the invention of printing with movable type in the 11th century : In the Meng Xi Bi Tan ( Chinese 夢溪筆談 ; German: "Brush entertainments on the dream brook") he describes the method of Bi Sheng , which however not enforced. Wang Zhen (1260–1330) later used movable wooden letters .

Only Emperor Kangxi , who came to power in 1661, had movable characters produced again at the suggestion of Jesuit missionaries , but only to a small extent. A later emperor had the letters cut in copper melted down due to a lack of money, and in the 19th century, books were still being made in China as wood board prints, as they had been 1000 years earlier. Material evidence of early book printing with mobile letters in China does not seem to be found to this day.

Korea

The oldest Korean block prints are Buddhist spells, dharani from a pagoda of the Bulguksa temple in Gyeongju from the first half of the 8th century.

The Tripitaka Koreana , a Buddhist canon created in Goryeo , which was printed in 6000 volumes with 81,258 wood printing blocks , is also considered a tremendous cultural achievement . Due to the number of printing blocks, it is usually called eighty thousand tripitaka (八萬 大 藏經) in East Asia . The production of all the wood printing blocks took 16 years (1236–1251). It is particularly noteworthy that all of the printing blocks in a well-ventilated historic building of the Haeinsa monastery are still in very good condition. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek has retained an early copy of chapters 69 and 81 of the Mahāprajña-parāmitā and the three-volume Hongmyǒng chip (弘 明 集).

In Korea , individually cut metal letters were probably developed as early as 1232.

The invention and use of metal letters in Korea occurred during the time of Goryeo . The exact date of the invention can no longer be traced with absolute certainty. The 11th century is sometimes mentioned, other sources date it to the 12th century. An author of this period mentions in his work published in 1239, which was published as a wood print, that metal letters were used before 1232. The famous scholar Yi Gyubo ( Kor. 李奎 報 , 1168–1241) also wrote in his masterpiece “Donggukisanggukjip” ( 東 國 李 相 國 集 ; Collected Works of Minister Yi of Goryeo) that 28 copies of the “Sangjeongyemun” ( 祥 定 禮文 ; ritual texts) were printed with metal letters.

One of the early still preserved printed works made of metal letters from Goryeo, “Baegun hwasang chorok buljo jikjisimcheyojeol” ( 白雲 和 尙 抄錄 佛祖 直指 心 體 要 節 or “Jikjisimgyeong” for short ( 直指 心 經 ); selected sermons by Buddhist sages and Seon masters ) , which was printed in the Heungdeoksa Temple in Cheongju, dates back to 1377. It is in the French National Library in Paris. The book is further proof that metal type was already common in the Goryeo dynasty. This second volume of the anthology of the Zen teachings of great Buddhist priests, Jikji for short , from Korea, printed in July 1377 , is the oldest known example of letterpress printing with movable metal type and, like the 42-line Gutenberg Bible, has been on the UNESCO register since 2001 World document heritage "Memory of the World".

Another source can be found in the book "Goryeosa" ( 高麗 史 ; story of Goryeo), in which it is stated that King Gongyang dass 讓 in 1392 the official authority "Seojeokwon" ( 書籍 院 ; book and publication center) the responsibility and supervision granted for all matters relating to the use of metal type and letterpress printing.

The Bavarian State Library owns a drug catalog printed in 1433 "with clay letters" for the medical work "Hyangyak jipseongbang" 鄉 藥 集成 方 , written on behalf of King Sejong , with the title "Hyangyak chipsŏngpang mongnok" 鄉 藥 集成 方 目錄 . (Bayerische Staatsbibliothek # Korean Collection) (Sign .: L.cor. M 7) Sejong also became known through the development of the Korean alphabet he initiated .

Japan

The oldest surviving prints in Japan were made by order of the Shōtoku - Tennō (764-770) with copper or wood blocks. She supposedly had a million paper rolls placed in small wooden pagodas printed, which is why these were also called Millionpagoda Dharani , Hyakumantō Darani . These were distributed to ten Japanese monasteries. Around 40,000 are still preserved, which is why many also ended up abroad. In Germany there is one copy in Berlin ( Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin ), two in Munich ( Deutsches Museum , Bayerische Staatsbibliothek ) and one in Mainz ( Gutenberg Museum ).

The Korean letterpress, Chōsen kokatsujiban ( Japanese 朝鮮 古 活字版 ) was not imported to Japan until the end of the 16th century, where it was only used for East Asian texts for 30 years. Whereas at the same time the Gutenberg technique was introduced by European missionaries, but was reserved for Christian and Western texts. These old letter prints are valued today in Japan as bibliophile incunabula. The Bayerische Staatsbibliothek lists nine such Japanese old letter prints (1991). Among them is one of the luxury prints by the painter Hon'ami Kōetsu ( 本 阿 弥 光 悦 ), which were called Sagabon ( 嵯峨 本 ), and a complete sentence by Kan'ei Gogyokoki ( 寛 永 御 行 幸 記 ), which depicts the visit of the Tennōs depicts the Shogun , the illustrations being printed with movable stamps, Katsuga ( 活 画 ).

middle Ages

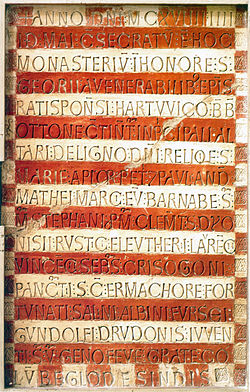

Some examples of knowledge of the typographical principle are known from the Middle Ages, such as B. the 1119 made in 1119 with stamping inscription in Regensburg. In the Cathedral of Cividale in northern Italy there is a silver altarpiece of the Patriarch Pilgrim II (1195–1204), whose Latin inscription was made with the help of letter punches. According to the art historian Angelo Lipinsky, this technique can also be found between the 10th and 12th centuries in storage and lip dispensaries of the Byzantine cultural sector , with which the Venetian Seafarers' Republic had close trade relations.

In the English Chertsey Abbey , the remains of a paving made of letter bricks were found, which were laid in the 13th century using the Scrabble principle. The technique has also been documented for the Zinna monastery near Berlin and the Aduard monastery in the Netherlands .

The period that followed did not offer a suitable basis for great inventions either, but it prepared one. What was left of learning after the fall of the Roman Empire and the Great Migration had almost exclusively sought the peace and protection of the monasteries . The Crusades, however, brought a fresher spiritual life, a certain interest in things beyond their own castle or city walls among the lay public, and from this gradually a desire for instruction and education of the spirit arose. This desire grew stronger as secular universities were established by free-minded rulers . The activity of the monks copying books was no longer sufficient for this. Their own copyists' guild formed alongside them, and this was probably the first reason for the so-called letter painters and map makers , from which in turn form cutters and letter printers emerged . This activity, which can be traced back to the beginning of the 13th century , was initially geared to the needs of the great mass of the people and adapted to their understanding. The focus was placed on the visual representation. The explanation by words was a very simple and irrelevant one.

But soon they were given a larger space, often in the form of tapes that wafted from the mouths of the people involved, until books were finally printed, albeit of a very small size, without any pictures, only with text. To make the printing plates, thin metal plates were first used, into which the drawing was engraved. Either only the outlines were left raised and everything else was cut away, or the reverse procedure was followed, i.e. only the outlines were cut into the plate so that they appeared white when printed, while the body of the figure and its surroundings were black had to stay. The process known as “Schrotmanier” produced the same result: Instead of cutting out the outlines, they were punched into the plate with punches so that they appeared as dense rows of small dots when printing. This was a practice that probably originated in the workshops of gold and silver workers. As the demand for pictorial representations became more and more generalized, there was a transition from metal plates to cheaper and easier-to-work wooden plates. The knife took the place of the burin, but the result could only be less good, partly because of the lengthways cut of the wood. The panels produced in this way are called wooden panels. The first one to be dated was a great Christophorus from 1423. Another woodcut kept in the royal library in Brussels , which shows the Mother of God with the Christ child, bears the date 1418. However, its authenticity has often been questioned. Whether these prints were actually prints, that is, produced with the help of a press, or rather were not produced only with the help of a grater, is a controversial issue in research. It is not unlikely that some form cutters used the press, others only the grater. But the fact is that those of their products that still exist are only printed on one side of the paper.

Of the books that have been printed without illustrations, as wood panel prints, the best known is a school book called Donat , a short excerpt in primer form from the linguistic theory of the Roman grammarian Aelius Donatus . However, it has not been proven that the printing of these donations took place a long time before the invention of letterpress printing, while it is certain that wooden panels were still used for their production than had been known to print with movable types for decades. Technical evidence even justifies the conclusion that typographically produced donations were overprinted on wood and the panels were then cut according to them. This is a process that can be explained by the fact that it was easier for the numerous book printers to cut entire plates with writing than to produce the individual types or to procure and assemble them. These panels also made smaller editions possible and their constant renewal if necessary, which was very worthy of protection given the preciousness of the parchment and the paper. Dutch letter printers appear to have repeatedly used the overprint process. However, there is evidence of wood panel prints in 1475 (Donate of Konrad Dinkmuth in Ulm), 1482 and still 1504.

Gutenberg, the inventor

Beginnings

Johannes Gensfleisch , named Gutenberg after the family residence of his parents ( Hof zum Gutenberg ), probably had to leave his hometown Mainz with his parents in the early 20s of the 15th century because of the unrest that broke out between nobles and citizens . He had stayed in Strasbourg . Only the arrest of the Mainz city clerk who happened to be in Strasbourg in 1434 gives certainty about his stay. It took place because of a considerable interest debt, which the magistrate of Mainz refused to pay to Gudenberg or Gutenberg, as the New High German spelling is. When the Mainz authorities promised payment, Gutenberg immediately released the town clerk. In 1439 a larger trial was negotiated against him by the heirs of Andreas Dritzehn, with whom he had concluded a contract, probably around 1435, to teach him and Andreas Heilmann how to cut stones (jewels, semi-precious stones). And since Gutenberg had also entered into a business relationship with a Hans Riffe in 1437 for the operation of mirror making (metal casting) for the healing trip to Aachen , Aachener Heiligtumsfahrt , it is clear from this that he had a special inclination and skill in and in the art-industrial professions (metalworking) must have had a well-founded reputation. The fact that he may have already dealt with the idea of his invention of the art of printing at that time seems to emerge from multiple statements of the witnesses in the process. The invention of printer's type in the form and quality which alone enable its composition for printing, as well as the invention of a corresponding color for this impression, were long planned. There is thus almost no doubt that those unclear, probably intentionally veiled statements in the Dritzehn process refer to the first beginnings of the art of printing. However, it is not certain whether he actually practiced it there, although the “Donatus” remnant, which is in the National Library in Paris, is Gutenberg's Strasbourg press product.

The contract with Fust

Documents about his money operations have shown that Gutenberg was in Strasbourg until March 1444. From then until 1448 all messages are missing. The first after that concerns a loan that he had received from a Mainz relative, Arnold Gelthuss, when he returned to Mainz. His efforts in Strasbourg had evidently been in vain, and with the loss of the trust his friends had placed in him, his fortune and credit had also been lost, so that his return to Mainz may have been a forced rather than a voluntary one. Here, however, he immediately resumed his attempts at printing. The fact that they must have come a long way shows that he soon managed to find support in the rich Mainz citizen Johann Fust . He signed a contract with him on August 22nd, 1450, according to which Fust Gutenberg gave a loan of 800 guilders in gold at 6 percent interest, but he was supposed to “do the work”, while all his tools would serve as pledge for Fust. If they did not agree, Gutenberg had to return the 800 guilders to Fust, but his tools would then be mortgage-free. In addition, Fust was supposed to pay 300 guilders a year “for costs, rabble wages, house rent, parchment, paper, ink, etc.”. This was a condition that he never met. On December 6, 1452, Gutenberg had to raise 800 guilders from Fust again.

Gutenberg's first prints

What Gutenberg has created in the meantime cannot be precisely determined. Presumably he was busy making the types for the 42-line Bible. These were used in the printing of a “Donat”, the remainder of which bears the handwritten date 1451, as well as, in addition to another smaller type, were used to print letters of indulgence , of which a considerable number of copies have survived. That these could not have been printed from wooden panels is irrefutably proven by the occurrence of an inverted letter in one of them.

The assumption that Gutenberg first used movable wooden letters has long since been rejected because their application would have been technically impossible, quite apart from the immense and time-consuming effort of cutting each one of the thousands of types. It is more likely that he first cut the type stamps out of wood, molded them in sand and then poured them. Soon, however, he will also have abandoned this inadequate and slow process and cut his dies into the hardest possible metal, which he then converted into molds or matrices for casting the types by hammering into a softer one. The regularity and evenness of the letters in the 42-line Bible speaks for it. The font is therefore no less an invention of Gutenberg than that of the printing press, because before him, as already mentioned, the form cutters and letter printers had probably without exception used the rubbing device to produce their one-sided prints. The 42-line Bible as well as the 36-line and the Psalter of 1457 are such perfect printing achievements and show such a precise fit of the pages to one another (register) that they can only have been produced on a printing press. The printing color, which in the wooden panel prints before Gutenberg usually appears in a matte earth brown, was adapted and perfected by him for his purposes.

Loss of printing to Fust

Soon after the completion of the 36-line Bible, of which probably only a small edition had been printed, the printing of another, also in Latin, but with smaller types, which is now called 42-line, began. It was, however, not yet completed when Fust approached him with the demand that Gutenberg should repay him all the capital he had borrowed, along with interest. The fact that Fust knew that it was difficult to repay Gutenberg at the time, as well as the entire version of the contract, made Fust suspect that he had been interested in his invention from the start, but in monetary matters impractical Gutenberg and with him also his invention completely in his own hands. He succeeded completely after he had a substitute for the technical continuation in Peter Schöffer instead of Gutenberg. Schöffer, a beautiful scribe from Gernsheim, may only have been employed in Gutenberg's printing works as illuminator and rubricator of the finished printed sheets in order to add the capital letters in the empty places, perhaps he was also active as a type draftsman or typesetter.

After Fust had succeeded in having Gutenberg revoke the printing works and all finished prints, Schöffer took his place and eventually became Fust's son-in-law. In October 1455, Fust filed his lawsuit for repayment of 2,026 guilders including interest and compound interest (he pretended to have borrowed part of the money "from Christians and Jews "). On November 6th, in the great “Refender” of the Franciscans, the verdict was passed, condemning Gutenberg to billing and payment or, if the latter was not possible, Fust exercised his contractual rights.

Continue work

Gutenberg, although almost 60 years old, remained unbroken, as he had succeeded in his invention. This circumstance soon provided him with other material help: Konrad Humery, Mainz city counsel and city clerk , became his financier. The types of the 36-line Bible, probably not made with Fust's money, seem to have been taken over to the new printing company he was now setting up, and with these or similar types he initially printed smaller undated fonts while simultaneously working on the Cut to the smaller type, which was used to produce his great work, the “ Catholicon ” (“ Joannis de Janua summa quae vocatur Catholicon ”), a grammatical-lexical compilation. The work comprises 748 folio pages of 2 columns with 66 lines on each and bears the year of completion, 1460, but not the name of Gutenberg, as this is not found in any of his prints, which can only be explained by the assumption that either the master was enough of himself in his work and his success meant more to him than all the applause in the world, or - that he was not allowed to call himself publicly as a printer, he did not want to attract unsatisfied believers from earlier periods to his neck and do his work again seriously endanger.

Retirement

When Mainz was stormed on October 28, 1462 by Adolf von Nassau , the opposing bishop Diethers von Isenburg , to whom the Mainz team stood, the Fust and Schöffersche printing works went up in flames. Whether Gutenberg continued to print in Mainz afterwards or whether he had already relocated his printing works to Eltville in the Rheingau , where the Nassauer court held and where they then took over his maternal relatives, Nikolaus and Heinrich Bechtermüntze, cannot be historically proven. nor what has been printed under his own direction. However, a number of small books are likely to be fully justified ascribed to him.

Gutenberg retired on January 18, 1465. Elector and Bishop Adolf von Nassau accepted him by decree for life as court servant for the “pleasant and willing service that his dearly loyal Johannes Gutenberg rendered to him and his pen”. As a result, Gutenberg was relieved of all material worries about the future, but did not enjoy the rest for long. He died in the first days of February 1468, as can be seen in the book of the dead of the Dominican monastery in Mainz, which was only found again in 1876 and in whose church the grave of the Gensfleisch family was located. The tomb itself has remained undiscovered since the church was destroyed by the French when Mainz was bombarded in 1793.

Successor to Gutenberg

Gutenberg's print shop, which had been dedicated to the Humery, was transferred to the Bechtermüntze, from which it came to the brotherhood of common life, the so-called Kogelherren zu Mariathal, near Eltville, in whose hands it remained until 1508. In that year it was sold by them to Friedrich Hewmann, printer in the Kirschgarten in Mainz.

After Fust took over Gutenberg's printing house in 1455, he took Peter Schöffer as a partner, and in 1457 they published the Mainz Psalter , which is still regarded as an extraordinary printing achievement today . This was also the first printing work to name the printer and the place of printing and to specify the year and date of publication. The text is printed with a large missal type and adorned with magnificent initials in two colors. A second edition of the work was completed on August 29, 1459. Four more editions followed in 1490, 1502 and 1516, the latter by Schöffer's son Johann. The later editions, however, do not resemble the completion of the first, and this circumstance, as well as the short period between the publication and the forced resignation of Gutenberg, suggests that it was the inventor himself who drew up the plan for the Psalter, the preparatory work carried out and maybe even printed part of the work himself. The character and beauty of the font also speak for Gutenberg's authorship. Of the large initials printed in two colors, the exact manufacture of which has often aroused the admiration of scholars and experts, it has recently been proven with reasonable certainty that they were not produced in the now common way of simultaneous two-color printing, but that one Painted colors on the types cut in metal with a brush and then printed them at the same time as the previously blackened text. Of Fust and Schöffer's larger printed works, the "Rationale Durandi", the "Constitutiones Clementis", which was completed on October 6, 1459, dated June 25, 1460, and a Latin Bible of August 14, 1462, printed with the text type of the "Constitutiones". However, none of these types are as perfect in cut and cast as the fonts produced by Gutenberg. There is little evidence of their activity after the storming of Mainz from the years 1462–1464, even if the use of the Bible type shows that the printing house could not have been completely destroyed in the house fire. It was not until 1465 and 1466 that larger printed works were brought back: “Bonifacius VIII. Liber sextus decretalium”, “Cicero de officiis” and the “Grammatica vetus rhythmica”. But Fust had already traveled to Paris in 1462 to sell his Bibles there, had found a very courteous reception with the king himself, set up a book store there and returned in 1466 to where he probably died of the plague in late summer of the same year . After Fust's death, Schöffer remained at the head of the print shop and now appeared for the first time with the claim to the invention of the art of book printing in his prints, which only came to perfection through his perfecting of the font. His claims fall apart before critical technical research, because the types cut and cast by him are far behind Gutenberg's achievements in number and quality.

Even further than Peter Schöffer, who died at the beginning of 1503, his descendants went in denial of Gutenberg. His son Johann followed him in the management of the print shop, and his name appears for the first time in the final text of "Mercurius Trismegistus" of March 27, 1503. The second son, Peter Schöffer the Younger , left Mainz in 1512 and initially went to a print shop to Worms and then to Strasbourg, where he appears as a printer in 1532. His son Ivo succeeded his uncle Johann zu Mainz in 1531 and continued the business until 1552. With his death, the Fust-Schöffer printer family died out, and the printing works came to Balthasar Lips through his widow. Why the Mainz Johann own son Johann, who had moved to Herzogenbusch in Holland (called Jan Janszoon there), did not return to take over his father's printing company is not clear. This Mainz Johann, however, with his lies contributed a lot to the confusion of the history of the invention of the art of printing, because while Peter Schöffer still dared not deny Gutenberg as the first inventor, even if he played himself as an improver and finisher of the art of printing, Johann Schöffer said as early as 1509 that his grandfather Johann Fust was the inventor. And in 1515, in the “ Breviarium historiae Francorum ”, he repeated this list very extensively, forgetting or suggesting that the world had forgotten that in his dedication to the “ Roman History ” of Livy dedicated to Emperor Maximilian he had asked his patron to "To accept this book that was printed in Mainz, the city where the wonderful art of printing was first invented by the artful Johann Gutenberg in 1450".

technology

Printing process

The printing process in traditional letterpress with old presses consisted of several phases. After the printing form , on which all the elements to be printed are raised, had been set, it was lifted into place. To do this, the press master took the form and placed it in the cart on the press table. It had to be in such a way that the frames lay exactly on the bars of the form. This was especially important when it came to the perfecting . The process was known as registering. An unprinted sheet of paper was then attached to the lid.

Then the paint was mixed and spread on a stone. With two Printers bales color was taken from the stone and rubbed on the printing form. In order for the ink to be absorbed by the paper, the sheet had to be moistened a day before printing. Inking the printing form was difficult in that it was not allowed to apply too much or too little pressure on the sentence to be inked, as otherwise individual types could separate from the sentence.

Then the frame was folded onto the arch. Without a frame, stops had to be attached to get a fitting angle for the lid. The stops consisted of two wooden or metal blocks and thus always kept the printed sheet in the same position. Tissues were placed between the paper and the lid as an intermediate layer. These were held in place by the inner lid. Without this intermediate layer, the crucible would crush the types . After the lid was pressed onto the mold, printing was done . For this purpose, a spindle with thread and point, which ran through a guide, the so-called bushing, was directed onto an iron plate. This plate is the crucible . The crucible was always smaller than half a sheet of paper. Crucible and can are connected by cords. The spindle itself turned in wood or metal threads in a crossbeam connecting the two large uprights of the press. The plunger was inserted through a hole in the spindle. The spindle and thus also the crucible could be moved up and down with the press lever. So the rotation of the spindle could not be transferred to the board, which presses the paper onto the printing form. Otherwise the paper would shift and smear the paint. The opposite side of the press bar was a stable table in which the cart could be moved back and forth on rails. To print, the lid was folded down and the cart pushed under the crucible. A jerky movement of the kid printed.

After pressing, the cart was moved out again and the lid and frame folded up. The sheet was removed and hung up to dry or stapled to the cover for reverse printing. If the status of the typesetting deviates from the norm, it becomes apparent that there were no hinge-like connections between the printing forme and the foundation on the one hand and the cover on the other.

A signature was already attached to the B42 , manufactured by Johannes Gutenberg , in order to keep track of things while the work was being printed, as several people often worked on one work in different rooms. The signing took place either before printing with the provision of the material on the press ready for printing or after printing between the laying out and hanging up of the printed sheet.

After printing, the form had to be unhooked and all the components used, for example the set and printer pads, had to be cleaned.

A distinction is made between single- phase and two-phase pressure . With single-phase printing, only one sheet is printed at a time. With two-phase printing, two folio pages are placed side by side in the press and printed one behind the other. This has the advantage that the cart only needs to be moved a little further when printing the second sheet instead of having to perform two complete printing processes.

finishing

There is hardly any information about what the lifting of the finished printing form looked like. Furthermore, it is only assumed what material the base was made of and whether it was used directly in the press or with a base on the foundation. Since the foundation, the cover and the printing forme were initially separate elements of the press, the cover could be prepared outside the press. First the elevator was attached. This consisted of several moistened paper layers. The printed sheet was then needled. To do this, loose pins were pinned to the board. From the 16th century , thin nails were attached to the lid for this process. Finally, the set was trimmed, that is, parts that were too weakly printed were underlaid with small pieces of paper.

Development of the printing press

The press for book printing developed in the 15th century from presses for winery, textile printing and paper production and consisted of wood until the 19th century . They worked on the principle of printing flat on flat.

The early wooden press

In the 15th century, wooden screw presses were used for pressing and winemaking, for pressing paper and for various pressing processes. The most important components of a press were two vertical beams standing on short foot beams, which later developed into press walls. These were connected horizontally in at least two places in order to be able to keep the connection required for printing. A first crossbeam was attached to the upper end of the vertical beam. The second cross beam was attached to the lower end of the press in such a way that the spindle only filled about half of the hole in the beam when it reached its lowest position, which was the case with the contact pressure. This was possible because both bars had a hole for the spindle. In addition, a press had a press lever which enabled the spindle to be pulled up and down. A cover board lay loosely on the substrate and the printing form . This first basic construction was not really suitable for printing and was continuously improved.

Gutenberg's printing press

Johannes Gutenberg changed the wood press in such a way that it could be used for effective and productive printing. He placed the table between the press walls so that it protruded as far as possible on the working side. The pan moved up and down to prevent the ink from smudging. The crossbeams were set lower. As a result, the upper spindle could be guided better. Instead of the beam, a strong board, the so-called bridge, was used. A rectangular opening was made in the middle to allow the vertically movable bush to be installed. A recessed ring was cut in the spindle under the hole. In turn, the rifle hung, which could be moved up and down in the opening. At the bottom was the crucible. The spindle settled on the platen during the printing process. It was important to maintain a certain distance between the crucible and the printing form so that when the pressure is applied, the crucible can lower onto the printing form and print correctly. During the printing process, the mold and the foundation were pushed together under the crucible. The correct position was fixed with stops, for example with wooden blocks. If the pulling rod (press lever) is pulled, the spindle is lowered. At the same time, the can and thus the crucible are lowered. In this way, the contact pressure was transferred from the spindle to the lid via the crucible. The lid was slightly larger than the crucible and could cover half a sheet (later, i.e. after 1460/1470, two half sheets of the front or reverse). It was important that the lid was made of warp-free, strong wood. This ensured the correct translation of the sentence when printing on the substrate . The base for the printing form consisted of a flat stone or metal plate.

A press was usually so large that the contact pressure that could be achieved with it was sufficient to print a folio page.

The wooden press in the 16th century

In the 16th century the press was further improved. The cart was driven with a crank and the spindle beams were adjustable by means of lag screws. The crank did not have to be released between the kid pull and kid push. This made the printing process faster. The contact pressure became less and the print format smaller. The crucible was firmly attached to the can to prevent it from tipping over. This uneven placement of the crucible had mainly occurred when the set of the side to be printed had free corners that were not to be printed or the cart was not properly positioned under the crucible. In the course of time, four crucible hooks were attached with cords. Instead of wood, parts made of metal were now processed in the press.

At the end of the 16th century, a press consists of two press walls that stand vertically on feet and are connected to each other by crossbars. The press is attached to the upper part by means of supports and bolts. The spindle sits vertically between the press walls and is in turn attached to the top of the nut. The spindle leads down through the bushing with the tip on the fitting of the crucible. The metal spindle made printing easier in that it could be oiled. It ran lighter than a wooden spindle and hardly transmitted any vibrations to the press when it was turned.

The iron crucible was now as big as the entire area to be printed and fastened with rings. These had developed from the crucible hooks. This led to a more secure hold of the individual metal parts and the tilting of the crucible and the associated damage to the set could be prevented. The spindle was also made of metal and had a handle. The press boy was thus also made of iron. This brought some advantages. The kid could now be bent so that the printer no longer had to lean far over the printing table. Furthermore, the kid had more elasticity. This enabled the printer to influence the contact pressure to a certain extent.

The printing table was under the pan. This consisted of two horizontal rails on which the cart ran. This in turn was connected to the rails by iron clips. The cart could be moved back and forth with a hand crank. The printing form was placed on a marble or stone plate and fastened at the corners with angle iron. The large and the smaller lid are connected by hinges.

In 1507 the first printer's signature appeared in a book that Jodocus Badius Ascensius from Ghent had printed in Paris.

The invention of type printing

Johannes Gutenberg improved the inventions that had been made up to then and merged them into a uniform work process.

The cities that expanded printing technology in addition to Mainz were Strasbourg , Bamberg and Haarlem in Holland.

Johann Mentel, Strasbourg

Strasbourg asserted its claims in two ways. One calls us Johann Mentel (Mentelin) from Schlettstadt as the first printer and inventor. This property was first assigned to him in 1520 by Johann Schott, his son-in-law and heir of the Mentel printing house. The chroniclers Specklin and Spiegel believed him and, through the chronicles they wrote, contributed significantly to the spread of Schott's false statements.

Mentel was a fine or gold scribe who acquired his citizenship in Strasbourg as early as 1447 and probably became acquainted with him during Gutenberg's stay there and was later recruited by him to Mainz as an assistant in the drawing and production of the types. He was able to learn letterpress printing. But he must have returned to Strasbourg very soon. Presumably, the termination of the business relationship between Gutenberg and Fust in 1455 was the cause. Joh. Philipp von Lignamine zu Rome writes in 1474 that Mentel had owned a printing works in Strasbourg since 1458, where he printed 300 sheets a day, "in the manner of Fust and Gutenberg". In the Freiburg University Library there is indeed a printed Latin Bible, the first part of which, concluding with the Psalter , has been given the date 1460 by the rubricator, while the second at the end of the Apocalypse bears the year 1461 in the hand of the same rubricator .

Schott was probably only induced to give false information by the example of Fust and the Creator. In the 18th and 19th centuries he found devout followers and representatives in Schöpflin (“Vindiciae typographicae”, Strasbourg 1760), Oberlin (“Exercice public de bibliographie”, that. 1801), Lichtenberger (“Initia typographica”, that. 1811 ), after a Parisian doctor, Jacques Mentel, an alleged descendant of the Strasbourg printer, had refreshed the already forgotten story to glorify himself in the 17th century . But Johann Mentel died in 1478 and was buried in the cathedral in Strasbourg. The first Strasbourg print, dated 1471, with a printed date, the “Decretals” of Gratian , does not bear his name, but that of his contemporary Heinrich Eggestein or Eckstein. Mentel's first dated work is from 1473.

Albrecht Pfister, Bamberg

Even more generally than for Mentel, Albrecht Pfister zu Bamberg did not always appear as the first inventor, but rather as a co-inventor of the art of printing at the same time as Gutenberg. The printing of the 36-line Bible was himself regarded as his work until the end of the 19th century. Only after serious comparative studies of the typeface character of the types used by the first book printers and the relative quality of their printed products have been made that a work by Gutenberg, namely his first large, the 42-line Bible, has been recognized and the agreement The types of the same with the few prints of a small size that bear the name Pfister consequently explain that Pfister, like Mentel, was a student of Gutenberg who also left Mainz when Gutenberg handed over his printing works to Fust in 1455. Mentel bought Gutenberg's types that had been used to print the text of the 36-line Bible.

The fact that Pfister did not cut or cast them himself is proven by the fact that he only used this one type for all of his prints, even when it had already become very inconspicuous through use. Pfister's German prints show that this type must have served to print an extensive Latin work earlier, in which all the letters occurring in Latin are worn out, but the ones that are only used in German (k, w, z) appear new and sharp . Pfister's prints, insofar as they can really be recognized as having been made by him, are, with the exception of one, richly illustrated with woodcuts . Before he resorted to type printing, their creator was his profession as a form cutter.

The fact that several copies of the 36-line Bible were discovered in Bamberg and its vicinity suggests that there must have been closer relationships between him and Gutenberg. Finding these Bibles and the statement by Paul of Prague from 1463, which seems to have been intended to explain the word “libripagus” for a kind of encyclopedia, “that during his presence in Bamberg a man cut the whole Bible into wooden panels and I printed it on parchment within four weeks, ”are conclusive evidence of Pfister's printing of the 36-line Bible. It can only mean a “Biblia pauperum” (17 folio sheets with woodcuts) in Latin and German editions, because an entire Bible has never been cut in wood. At that time it would not have been possible to produce such a comprehensive work in print in the short time mentioned. The works that have a date and Pfister's name are a second edition of “Boners Edelstein”, 1461. This is the first book in German which clearly shows the place and year of printing , as well as “The Book of Four Histories” from the year 1462. After this year there are no more printed works with his name. The year of his death is unknown. When he started to print in Bamberg cannot be determined either. Because of the family resemblance of his prints, he is ascribed the "Eyn manung d 'cristeheit widd' die Durcke", but this has to be moved back to the year 1455 with reference to general history, further questions remain unanswered. It is possible that he himself printed the “Manung” in Mainz under Gutenberg's direction. Their small size and the lack of all woodcuts in this work seem to indicate this.

Laurens Janszoon Coster, Haarlem

Of greater importance for the history of the invention of the art of printing, if only because it has found far more general dissemination and more numerous adherents than the above theory, the claims that Holland, and especially Haarlem , made for Laurens Janszoon Coster have been . Two printers in the city, van Zuren and Coornhert , who founded a printing house there in 1561, first tried, probably based on existing old wooden plate prints, to claim Haarlem as the place where the art of printing was invented . A book that van Zuren is said to have written about it has never been found and was only mentioned by Scriver in 1628 in his "Lavre-Crans voor Lavrens Coster" by title. In the preface to the “Officia Ciceronis” published by him, Coornhert describes the invention as “first made at Haarlem, although only in a very crude way”, without naming an inventor. The Florentine Luigi Guicciardini did the same in his “Descrittione di tutti i paesi bassi”, completed in Antwerp in 1566 . This work, which was soon (1567–1613) translated into German, French, Dutch, English and Latin, contributed greatly to the spread of Haarlem's claims. However, they were only given a rounded, solid form by the historiographer of the states of Holland, the doctor Hadrian de Jonghe, called Junius († June 16, 1575), who wrote a Dutch national history between 1566 and 1568 under the title: "Batavia", which was printed at Leiden in 1588 . While his three contemporaries are still uncertain and do not name an inventor, he mentions the following:

Then 128 years ago (i.e. 1438 if you count back from the year in which he began to write his "Batavia", or 1440 if you consider the year of completion) a man named Lourens Janszoon in Haarlem was looking back called “Coster” on his stand as a sexton, who once cut out letters from beech bark while taking a walk in the wood in front of the town to pass the time , put them together into words and then printed them in ink as toys for the children of his son-in-law Thomas Pieterzoon . The writers' usual, easily flowing ink had proven unsuitable for printing, and with the help of this son-in-law he had succeeded in inventing a better and thicker color. The first books that were created in this way were only printed on one side, but the unprinted pages were glued together. One of them, written in the vernacular, is the "Spieghel onzer behoudenis" (the Dutch edition of the "Speculum salutis"). Gradually, the inventor Coster switched from beech wood types to lead and from these to tin due to the greater durability of the material. The new art had the well-deserved applause from the people, the printed books had found many buyers and thus brought prosperity to the inventor. As a result, Coster had to increase the number of his workers and assistants, among whom there was then a certain Johannes (also a Faustus is mentioned in an unclear way). This had proven to be a very unfaithful servant, because as soon as he was sufficiently instructed in type casting and typesetting and whatever else belonged to the art, he seized the first favorable opportunity, and for this the holy Christmas Eve seemed to him the most suitable, when everyone else attended the service to sneak into the study, pack up guys and tools and flee quickly. He first went to Amsterdam , then to Cologne and finally to Mainz, where he felt so safe that he opened a printing house himself, which brought him ample income in just a short year. It was around 1442, when he is said to have already printed and published the “Doctrinal” of Alexander Gallus with the same types that Coster had used in Haarlem.

Belief in this theory persisted for a long time. A combination of various circumstances led to this result. The frivolous forgery of Junius found ground in the nationality of the Dutch. But their closest and most ardent propagators were scholars. Some of them, who felt the weaknesses of Junius' fable, tried to add to them. The fight for and against Coster has in part been waged with great bitterness. However, it was only Antonius van der Linde who opposed the Haarlem claims in 1869 in a series of essays, which he then published in an improved and expanded form in 1870 under the title: “The Haarlem Coster Legend”, was decisive In 1878 his main work: "Gutenberg, Geschichte und Erdichtung" (Stuttgart) followed. Concerning Haarlem in particular, he proves that the first book printed there, which this city bears as the place of printing and as the printing year 1485, was "Dat suffer Jesu", but the printer called himself Jacob Bellaert von Zierikzee. The 32 woodcuts contained in the work had already been used a year earlier by Gerard Leeu zu Gouda to print the same book. In 1473 Dierik Martens zu Aalst in Flanders and Nicolaus Kettelaer and Gerhard de Leempt in Utrecht were already printing. So Haarlem does not even have the right to claim that it was the first city in Holland that historically demonstrably owned a printing company. The testimony of a bookbinder, Cornelis, in favor of Coster does not stand before historical criticism, as does the family tree of a certain Gerrit Thomaszoon, kept in the museum in Haarlem, who is said to have been a descendant of Coster's motherly side, but who was an innkeeper in Haarlem . Exact research in the Haarlem city archives and church registers about the person Coster has only shown that around 1446 a man of this name lived in Haarlem who ran a shop for salt, candles, oil, soap, etc., but started an inn in 1456 and this one operated until 1483, after which he moved from Haarlem unknown. No historical events are known of Lourens Janszoon Coster, the inventor of the art of printing in honor of a monument that was unveiled in Haarlem in 1856.

Multicolor printing

Initially, the red printing for rubrications and the printing of the book decorations were carried out in a separate printing process. Larger images can be easily colored in the printing form and printed. The printing block of each initial was composed of several parts made of metal. It consisted of the actual letter and the ornamentation . The latter was made up of several parts and made up a so-called ornamental block. This had a multi-line recess for inserting the letter.

Separate metal plates were made for printing initials and woodcuts . There were two ways to print images and colors in one print with the text.

On the one hand, after the set was completed, the typesetter was able to remove all parts to be printed in color from the set and color them separately. The text has been colored black. After coloring all parts, the set was reassembled. This process was repeated each time the sentence was colored again. The prerequisite for this option was a device that allowed individual letters to be removed without moving the entire set.

The second option was to collect the sentence, including the initials, etc. in the press. Then a template was created, which covered the types to be colored red and the initials. First, the uncovered areas were colored blue, as this corresponded to the smallest area to be colored. Then a second stencil was placed and the printing form was colored red. Finally, the black color was added. The stencils were made of parchment or thin sheet metal. This option was more time-saving than the first mentioned.

Picture printing

In the 15th century the picture printing was based on wood and metal sections in the high-pressure principle made. Most of the time these prints were black. First, the printing blocks were drawn as contours and then colored. The coloring was done either freehand or using a template.

At the end of the 15th century there was a differentiation in the design, in the insertion of drawings and in the gray values. Especially Albrecht Dürer coined this time. The text and image were now printed one after the other. The technical problem was to get the same height of the printing block and types, to find a suitable printing ink for both elements and to develop a locking technique for the entire form. Printing the individual elements one after the other brought with it the problem that the text and the image overlapped. Conversely, however, there is no clear evidence that the two parts overlap that the printing took place in two steps.

Spread of the invention

In the 15th century, the invention of the printing press spread very quickly. This was mainly possible due to the well-developed trade routes.

- 1458 first printer in Strasbourg

- 1462 in Vienna

- 1464 in Basel

- 1465 in Cologne

- 1467 in Eltville

- 1468 in Augsburg

- 1470 in Nuremberg

- 1472 in Ulm

- 1473 in Spain and England

- 1593 in Mexico

While there were still 17 printing locations in 1470, their number increased to 204 printing locations by 1490. By 1500 there were 252 printing locations, of which 62 were in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . In the early days of printing, average print runs of 150 to 250 copies were achieved. About 77% of all incunabula appeared in Latin. (Figures from Wittmann, Reinhard: Geschichte des Deutschen Buchhandels, p. 27). Initially, mainly letters of indulgence , calendars , donations and books were printed. Over time, large companies such as Anton Koberger's in Nuremberg emerged. This employed up to 100 workers on 24 presses. In the 16th century the printing of Luther's writings made up almost a third of the total print run. Until the 18th century, the method of hand-setting with movable type and printing remained almost unchanged.

The advent of the printing press led to a restructuring of the workshops. Now skilled workers in various professions became necessary. A new kind of intellectual exchange became possible.

The printer brought together all the work carried out. His area of responsibility was raising money and the components needed for printing. He hired workers, surveyed the book market, and issued newsletters and leaflets. At the beginning, the printer also had to take care of the sale of his products, which the bookkeepers did later . A division of labor between the technical department and the finance department started early on.

Germany

In Germany before 1462, apart from Mainz, only Strasbourg and Bamberg owned book printing plants in the Upper German-speaking area . Cologne received the next one from Ulrich Zell, who presumably turned there immediately after the storming of Mainz and began to print, even though Zell's first known and dated print dates from 1466. Cologne also became the starting point for the spread of printing in the Low German- speaking area to the Netherlands and Northern Germany . Eltville, which Gutenberg's printing house received, belonged to Mainz and can therefore hardly be named as an independent printing site. In 1468, however, one printed in Augsburg ( Günther Zainer ), Lübeck ( Lucas Brandis ) and Pilsen (in Bohemia ). In 1470 Nuremberg received its Johann Sensenschmid, who initially had Heinrich Keffer from Mainz as a partner. Sensenschmid moved to Bamberg, probably around 1480, where no printer seems to have worked after Pfister up to that point. In Nuremberg, however, the mathematician Regiomontanus printed in 1472–1475 and Anton Koberger or Koburger in 1473–1513 , who was called “the king of book printers” after the great expansion of his business and the excellence of his work.

Printing works also appeared: 1471 in Speyer , 1473 in Eßlingen , Laugingen, Merseburg and Ulm , 1475 in Blaubeuren , Breslau , Burgdorf , Lübeck and Trient , 1476 in Rostock ( Johann Snell ), 1478 in Eichstätt and Prague , 1479 in Würzburg , wherever Bishop Rudolf II von Scherenberg had appointed the Eichstätter book printer Georg Reyser, whose first work printed there, the “Breviarium Dioc. Herbipolensis ”, was also the first work in Germany to be illustrated by a copper engraving . Leipzig did not get its first print shop until 1481 through Andreas Friesner, former partner and proofreader of Sensenschmids zu Nürnberg. Vienna's first prints are dated 1482, but without the name of the printer; Johann Winterburger from Winterburg near Kreuznach is considered the first . In the same year, Johann Schauer first printed in Munich ; The printing press also found its way into Erfurt and Passau in 1482, a year later in Magdeburg , 1485 in Heidelberg and Regensburg , 1486 in Stuttgart , Münster , Brno and Schleswig , and 1491 in Hamburg . Although a number of larger German cities, in which the art of book printing later achieved excellent development ( Frankfurt am Main , Wittenberg , Dresden , Berlin, etc.) did not receive printing works until the beginning of the 16th century, at the end of the 15th century Gutenberg's invention and their products are already known everywhere and distributed throughout the entire German Empire.

Italy

It spread in Italy with even greater speed . As early as 1480, when there were only 23 cities with printing presses in Germany, Italy had 40. The first was built in the Monastery of Subiaco in 1464 by Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheym , whose most famous printing is the “Lactantius”. In 1467 they moved their printing works to Rome . Ulrich Han (Ulricus Gallus) had already settled here. His first print bears the year 1467. The number of Roman printing works increased steadily, so that by 1500 there were already 37 printers, 25 of them German. The number of printing works in Venice was even greater during the same period . There Johann von Speier (Johannes de Spira) introduced the art of printing in 1469, soon followed by Nikolaus Jenson from Tours , the pioneer of antiquatype , and Aldus Pius Manutius , who became famous for his classic editions, the so-called Aldinen . Filippo de Lavagna first printed in Milan in 1469; initially with him, from 1471 alone Antonio Zaroto, soon also Waldarfer from Regensburg. Foligno , Verona , Treviso , Bologna , Ferrara , Naples , Florence , Cremona , Messina saw the first prints in the same years, along with many other, less important Italian cities, whereby the strikingly large number of Germans who founded and first operated the printing works everywhere , most impressively described the invention itself as a German one. The first complete Arabic printing house in Italy was built by Gregor Gregorio from Venice at Fano at the expense of Pope Julius II .

France

France , which had become aware of Gutenberg's invention as early as 1458 and had sent Jenson to Mainz so that he could learn the art of printing, and saw Fust with his products on the Paris market as early as 1462, did not receive its first presses until 1470. Johannes Heynlin , called von Stein (Jean de la Pierre, Lapidarius) after his birthplace Stein (today Königsbach-Stein), and Guillaume Fichet , teacher at the Sorbonne , called the typographers Ulrich Gering, Martin Crantz and Michael Friburger (von Kolmar) to Paris, where they in built a workshop for the Sorbonne and delivered the first Parisian print in 1470 with “ Gasparini Pergamensis epistolarum opus”. This was followed by a Latin Bible, but the three printers soon seem to have separated, because in 1478 Gering printed alone and later had Wilhelm Maynyal and Bartholomäus Remboldt as collaborators. The second printing press in Paris was built by Petrus Caesaris (Emperor). At the time of Gerings death (1510) there were already more than 20. Gilles Gourmont was the first to print Greek and Hebrew works (1507–1508). The most famous book printers in Paris and France emerged over the centuries from the Badius, Stephanus (Etienne), Wechel and Didot families. The State Book Printing Office in Paris, 1640 under Louis XIII. founded, has contributed a lot to the development of printing in France; but this did not spread as rapidly across the country as it did in Germany and Italy. Guillaume le Roy and Buyer were the first printers in Lyon in 1473 . This was followed by Angers (1477), Chablis (1478), Toulouse and Poitiers (1479), Caen (1480) and others. a. in the following years.

Holland and Belgium

In all probability, Holland and Belgium received the art of printing from Cologne , and the first printing location to be proven by existing prints with the year and printer name is Aalst in East Flanders , where Dierick Martens (Theoderich Maertens) worked from 1473 to 1476. He first used a peculiar Dutch Gothic type with many corners and sharp edges and only later replaced it with one with rounded shapes. It is true that Johann von Westphalen, who was the first printer to appear in Löwen in 1474 , was said to have printed at Aalst before him; but there is no authentic evidence for this. Utrecht, however, undisputedly has the most justified claims to be regarded as the first printing location in Holland, since, as recent research has shown, it can be assumed that all the prints were made here on which the Dutch based their claims for Coster. Although none of these prints bears the name and year, important moments point to 1471, and the fact that the woodcuts of the "Speculum salutis", the main work of the unknown printer, were also used by the printer Johannes Veldener, who worked in Utrecht in 1478, but disappear after him seems to speak for it. The prints of this unknown printer are less forerunners of the art of book printing than the products of an inexperienced book printer who was apparently only a form cutter and wood board printer and who tried so well to put the little knowledge of the book printing company he might have to practical use he could, a circumstance which also makes the lack of printer name and place of printing on all of his works explainable. The first book prints received from the well-known cities of the Netherlands: 1475 Bruges , Colard Mansion; 1476 Brussels (Brotherhood of Living Together); 1477 Gouda , Gerard Leeu; Deventer , Richard Paffroad, and Delft , Jacob Jacobzoon; 1482 Antwerp , Matt. van der Goes. Haarlem appeared in 1483 as the 21st city in the Netherlands to receive a printer in Jacob Bellaert. The art of printing in Antwerp flourished in the 16th century thanks to Christoph Plantin, whose printing works drew the eyes of the entire learned world as the “eighth wonder of the world”. It remained in the hands of his family and successors for three centuries and, after it became the property of the city, forms the very special Musée Plantin. Amsterdam , which only had its first print shop in 1500, later became famous as a printing site alongside Leiden thanks to the Elzevir printer family, which flourished in both places from 1592 to 1680.

England, Scotland, Ireland

After England the art of printing from Cologne and Bruges was brought by William Caxton, an outstanding member of the merchant guild of London . His profession had taken him to Bruges, but whether he learned the art of printing here or in Cologne or in the Weidenbach Abbey near Cologne is just as open a question as where the first book in English, the collection of sagas “Recueil des histoires de Troyes ”, printed by him around 1471. In 1477 he had already returned to London and printed here as the first book "The dictes and sayings of the philosophers" in the district of the Abbey of Westminster . Simultaneously with him (1480 and 1481), John Lettou, William Machlinia (Wilhelm von Mecheln, 1481–1483) and, as Caxton's successor, Wynkyn de Worde from Lorraine, printed in London. Theodorich Rood or Rudt from Cologne first printed in 1478 in Oxford . In the Abbey of St. Albans from 1480–1486 an unknown printer worked, who referred to himself only as the "Schoolmaster of St. Albans". All other well-known cities in England did not receive printing presses until the 16th century or later.

The art of printing was introduced to Scotland in 1507. Walter Chepman and Andrew Millar were the first printers at the Scottish residence.

In Ireland , 100 years after its invention, in 1551, Humphrey Powell was the first to print.

Finland

First Book of Finland is of the Lübeck incunabula printers Bartholomew Ghotan produced Missale Aboense .

Switzerland

Beromünster in the canton of Lucerne (1470) was the first place of printing in what is now Switzerland , and Helias Helye , canon of the monastery there, was the first printer . The first book he completed on November 10, 1470 was the "Mammotrectus" by the Marchesino da Reggio, a dictionary to explain the Bible. In the 19th century, however, it was proven that the first printing from Basel can be dated back to 1468, as in the documents of the University of Basel as early as the early 60s of the 15th century a number of men who later became book printers are recorded were active, among them Ulrich Gering, one of the first three book printers appointed to Paris in 1469. The first printer named is Berthold Ruppel or Rippel von Hanau, a student of Gutenberg and one of the two “printer servants” (Bertolff von Hanauve) who had been sent by him to attend the negotiations of the Fustian trial against him in the large “Refender” . But there is only one print of his that bears his name and Basel, where he acquired citizenship, as the place of printing: the “Repertorium vocabulorum” by Magister Konrad von Mure . Adam Steinschaber from Schweinfurt first printed in Geneva in 1478. In Zurich, the first printing company worked from 1479–1481 in the Predigerkloster there ( Predigerkloster Zürich ). It gained a special reputation as a place of printing through Christoph Froschauer (1490–1564). The spread of the art of printing did not advance too rapidly in Switzerland during the 16th century. It came to Schaffhausen in 1577 , to St. Gallen in 1578 , and to Freiburg im Üechtland in 1585 . Einsiedeln , which owned the largest printing works in Switzerland in the 19th century, which belonged to the Benziger brothers , received the first printing works like numerous other Swiss towns in 1664.

Spain and Portugal

As in Italy, Germans were the apostles of Gutenberg's invention in Spain . A collection of 36 poems printed in Valencia in 1474 in honor of the Blessed Virgin is considered to be the earliest book printed in Spain. Four years later, in 1478, there is a printer's name, Lambert Palmart (1476–1494), at the end of a Bible that was published in a limousine translation. Matthias Flander printed in Saragossa in 1475, with Paul Hurus from Constance as the next successor; in Seville in 1477 three Spaniards were the first printers, followed by three Germans. 1478 Germans also printed the first books in Barcelona . In 1496, Granada saw its first printers in Meinrad Ungut and Hans Pegnitzer from Nuremberg. Pegnitzer had already printed in Seville beforehand. The art of printing found its way into Madrid in 1500; favored by the court, it soon flourished to a high degree.

In Portugal , printing was introduced by Jews. In 1489 Rabbi Zorba and Raban Eliezer of Rabbi Mosis Machmonides printed the Hebrew commentary on the Pentateuch in Lisbon with rabbinic types. Latin and Portuguese books were not printed until 1495 by Nikolaus from Saxony and Valentin from Moravia. Leiria in 1492, Braga in 1494, Coimbra in 1536, Viseu in 1571 and Porto in 1622 were given to printers .

Hungary, Czech Republic, Poland, Russia

Towards the east, the art of printing at Ofen in Hungary was welcomed by King Matthias Corvinus in 1472 , where the German Andreas Hess printed the “Chronica Hungarorum” at the expense of the court. In 1534 a second printing company was founded in Kronstadt . After that the expansion progressed more rapidly, and before the end of the century a sizeable number of Hungarian cities had printing presses.

In Bohemia , a "Trojan Chronicle" ( Kronika Trojánská ) printed in Pilsen is dated 1468 in the text, but today the information is mostly based on the handwritten original. The first prints in the Czech language, also from Pilsen, are two editions of the New Testament from 1476. In Prague the “Trojan Chronicle” was printed in 1487 and in 1488 the complete Bible. By 1500, over 30 prints in the Czech language have survived, including two complete editions of the Bible, three editions of the New Testament, three Psalter, etc. In Brno , Latin books have been published since 1484. Since 1512, printing in Hebrew has also been used in Prague (1518 and 1525 Pentateuch) and since 1517 also in Cyrillic ( Francysk Skaryna ). Several hundred editions are known from the 16th century, including magnificent picture books and the six-volume Kralitz Bible ( Bible kralická ).

In Poland , the first printing house was in 1491 to Krakow founded by Schweipolt Fiol , allegedly a pupil Koburgers in Nuremberg. Jewish typographers printed here with success from 1517, just as the Jews and the Jesuits in Poland, Lithuania and Galicia in general earned their credit for spreading and promoting the art of printing. In 1593 the first printer in Lemberg was Matthias Bernhart . Warsaw , where a traveling printer was temporarily active in 1580, did not get a permanent printing press until 1625.

Russia's first printing company is said to have been in operation in Chernigov in 1493 , but there are no more detailed data on this. Moscow got its first printer through a power ruling from Tsar Ivan the Terrible . In 1563 he ordered Ivan Fedorov, who had been a deacon at one of the Kremlin churches until then , “to make prints of handwritten books, as this would enable every orthodox Christian to read the holy books fairly and undisturbed as a result of the faster work and the lower price to speak and act according to them ". It is not known whether Fedorov was already involved in printing. The first completed printed work, an Acts of the Apostles , was dated March 1, 1564. The imperial printer, however, soon had to flee from the persecution of the copyists and came to Ostroh in Volhynia , where he finished printing the first Bible in Russian in 1583 . The art of printing in Russia only developed more vigorously under Peter the Great , who had fonts cut and cast in Holland and established the synodal book printing plant in Moscow in 1704, and in 1707 also released the printing company, which had previously been a state and church monopoly, to private individuals. Saint Petersburg received presses in 1710 immediately after its establishment. The tsar had them brought in from Moscow. No. 1 of the "Petersburger Zeitung" is dated May 11, 1711; the first book was completed in 1713. In 1588 a printer appointed by the German magistrate, Nikolaus Mollin, printed in Riga . In all other Russian cities and monasteries, printing was not practiced until the 17th century.

In Scandinavia , printing spread very quickly, which was also due to the high level of education of the population.

In Sweden , a traveling book printer was printing in Stockholm in 1474 . Johann Snell , a Lübeck resident, set up the first permanent printing house in 1483. In 1486, the printer Bartholomäus Ghotan , who also came from Lübeck, set up his own office in Stockholm for the first time . In 1495 they printed in Vadstena monastery , in 1510 in Uppsala , but not in old Lund before 1663 .

Norway's first print shop was in Trondheim in the mid-16th century , and Oslo saw the first in 1644.

In Denmark , the art of printing is said to have found its way to Odense on Zealand in 1482 through the same Johann Snell, who settled in Stockholm a year later . In Copenhagen Gottfried von Ghemen printed a Donat in 1490.

In Iceland , Bishop Jens Areson at Holum had the Swede Matthiesson printed the “Breviarium Nidorosiense” in 1531. In 1584, the first edition of the Icelandic Bible, illustrated with woodcuts, was published, printed by Hans Jensen .

In Greenland , the first printing press was set up around 1860 in the Moravian colony of Godthaab.

Turkey and Greece

In Turkey and Greece it was Jews who secretly practiced the art of printing, which Sultan Bajesid II had forbidden on the death penalty in 1483, in 1490. Ahmed III. finally gave permission in 1727 to set up a printing works in Istanbul , for which the tireless promoter of the same, Ibrahim Efendi, even cast the types according to samples obtained from Leiden in Holland.

Jews had already printed in Smyrna in 1658, likewise in Salonika in 1515 , in Adrianople in 1554 and in Belgrade in 1552 . In Greece proper, migrating Jews also printed in the 16th century. A printing company was founded in Corfu not earlier than 1817 . In Athens the first press was a gift from Lord Stanhope. Ambroise Firmin Didot gave Nauplia a printing shop as a gift, and Lord Byron set up a printing workshop at Missolunghi during the siege.

Southeast Europe

In the Obod monastery near Cetinje , the priest monk Makarije ran his first printing press around 1493, but it did not last long. After the monastery was destroyed by the Ottomans in 1496, Makarije moved to Wallachia , where he ran a new printing workshop in 1508. The first book was printed in Târgovişte in 1510 . Trojan Gundulić , originally from Dubrovnik , organized a printing workshop in Belgrade in 1552 in which the first Church Slavonic Bible was printed in what is now Serbia. A “prince” Radiša Dmitrović began to work, after whose death Gundulić took over the printing workshop and continued work. The monk Mardarije directed the printing.

Asia

In the non-European countries, missions contributed as much to the spread of the art of printing as trade and science .

In China and Japan it was missionaries who first used Gutenberg's invention. The Japanese letter prints, Kirishitanban ( Japanese キ リ シ タ ン 版 , Eng. "Christian prints "), which the Jesuits produced in Nagasaki at the end of the 16th century on a press imported from Goa, are considered to be great treasures. Only one copy exists in public libraries in Germany. The Bavarian State Library keeps the first volume of the Giya do pekadoru ぎ や ・ ど ・ ぺ か ど る (translated Guia de pecadores ) from 1599. The second volume came into the archive of the Jesuits in Rome.

This was also the case in Goa in the middle of the 16th century. And in 1569 a London mission company sent a full print shop and skilled workers to Trankebar. Rangoon , Singapore , and Malacca were given printing works by missionaries. After Calcutta a printing company first attained in 1778 by the Sanskrit researcher Charles Wilkins. In Madras you already printed six years earlier, and Bombay saw 1792 printer within its walls worked. From the Philippines , Manila is said to have taken up the art of printing as early as 1590. The first printing appeared in Batavia in 1668, in Ceylon in 1737, in Sumatra in 1818. In Persia , two printing works were not set up until 1820, in Tehran and Tabriz . In Syria , it was mainly the monasteries of Lebanon where printing was carried out. But Jews are said to have printed in Damascus as early as the 16th century . A master of the arts was the Melchite priest Abdallah Ben Zacher in the Mar-Hanna monastery, who in 1732 cut and cast his types himself and built his presses like the prototypographers of the first century of the invention.

From the Asian-Russian cities, printers received: Tbilisi 1701, Sarepta 1808, Astrakhan 1815, Kazan at the beginning of the 19th century, but in 1808 an institution for the printing of Turkish , for the needs of the Islamic Tatars . The art of printing has also found its way into the larger Siberian cities; Tomsk , Jenisseisk and Irkutsk printed government newspapers and for the needs of the administration towards the end of the 19th century, as did Blagoveshchensk on the Amur and Tashkent in Central Asia ( Uzbekistan ).

America

In America, it was Mexico whose capital, Mexico City , saw the first printing press. The German Johann Cromberger printed there in 1544. Jesuits printed in Lima in Peru in 1585 , in Puebla in 1612 and in Quito around the same time . And Brazil then had printing presses, although older prints are not known there and the earliest not go back beyond the beginning of the 19th century. Buenos Aires got the first printing house in 1789, Montevideo in 1807, Valparaíso in 1810, Santiago de Chile in 1818. In the West Indies , printing was done in Haiti as early as the beginning of the 17th century .

In the British colonies of North America , Halifax received the first press in 1766. In Québec , too, printing began before the War of Independence began . From what is now the United States , Massachusetts received the first press. A preacher, Glover, had taken the printer from England but died during the crossing, and it was left to his widow to set it up in Cambridge in 1638. John Daye took over the management of the printing house, followed in 1649 by his assistant Samuel Green. Philadelphia received a press from W. Bradford in 1686; the second printer there was Samuel Keimer, known as Benjamin Franklin's brother . Franklin himself, the most famous of all book printers after Gutenberg, did not produce any typographically excellent prints. Germantown saw the German Christoph Sauer as the first printer in 1735, who first printed a German newspaper, then in 1743 a German Bible. He also founded the first type foundry in America. W. Bradford, driven out of Philadelphia by Pietists , moved to New York in 1693, where he founded the first printing house and was involved in the founding of America's second paper mill , having previously participated in the first. The creation of the "New York Gazette" (1728) was also his work. After the end of the war of freedom, the art of printing spread over a large part of the Union states in the 18th century; but even during that time it had already promoted the cause of freedom mightily. The art of printing only crossed the Mississippi, the “Far West”, in the 19th century. California received its first presses in San Francisco in 1846 , Oregon in 1853 and Vancouver Island in 1858. And in New Echota, Arkansas , the Cherokee chief Seequah-yah published the “Cherokee Phoenix” in English and Cherokee in 1828 , for which he entered himself Had invented the alphabet of 85 characters .

Africa