Korean alphabet

| Korean alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Font | alphabet | |

| languages | Korean | |

| inventor | King Sejong | |

| Emergence | 1443 | |

| Usage time | 1446 until today | |

| Used in |

Korea China |

|

| Officially in |

North Korea South Korea People's Republic of China |

|

| ancestry | possibly z. T. from the 'Phagspa script Korean alphabet |

|

| particularities | Letters are combined into syllables | |

| Unicode block |

U + AC00..U + D7AF U + 1100..U + 11FF U + 3130..U + 318F |

|

| ISO 15924 | hillside | |

|

||

The Korean alphabet ( 한글 Han'gŭl, Hangŭl , Hangul , or Hangeul or 조선 글 Chosŏn'gŭl ) is a letter font that was developed for the Korean language . It is neither a logographic font like the Chinese characters nor a syllabary font like the Japanese hiragana or katakana . The modern Korean alphabet consists of 19 consonant letters and 21 vowel letters, which can be reduced to 14 characters for consonants and 10 characters for vowels. The individual letters are combined syllable by syllable so that each syllable fits into an imaginary square. The Korean alphabet was created in the 15th century and, with minor changes, is now the official script for Korean in North Korea, South Korea, and the People's Republic of China.

In this article the pronunciation is always given in IPA . Phonetic transcriptions are in square brackets […], phonological transcriptions between slashes /… /; Speech syllables are separated by a period. Transliterations of Korean spellings are in angle brackets ‹…›.

Names

|

"Folk writing ": [ əːn.mun ], 언문 / 諺 文 |

|

Chosŏn'gŭl : [ ʦo.sən.ɡɯl ], 조선 글 / 朝鮮글 |

|

"Our script": [ u.ri.ɡɯl ], 우리 글 |

|

Hangeul (Han'gŭl) : [ haːn.ɡɯl ], 한글 |

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the script was mostly called "Volksschrift".

In North Korea and China the script is called Chosŏn'gŭl , after the state name [ ʦo.sən ] 조선 / 朝鮮 or after the name of the ethnic group in China, or simply "our script".

In South Korea the font is z. Sometimes called "our script" just like in North Korea and China, but mostly Hangeul , corresponding to the state name [ haːn.ɡuk̚ ] 한국 / 韓國 (Han'guk) ; this name was first used by the linguist Chu Sigyŏng ( 周 時 經 ; 1876-1914).

shape

The modern alphabetical order of Korean letters, as well as their names, are slightly different in North Korea and South Korea.

Consonants

The following table lists the consonant letters with the McCune-Reischauer - (MR), the Yale - and the so-called " revised Romanization " (RR) of the South Korean Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

| Letter | phoneme | Name (North Korea) | MR | Yale | RR | Notation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㄱ | / k / | ki.ɯk̚ | 기윽 | k / g | k | g / k |

|

| ㄴ | / n / | [ni.ɯn] | 니은 | n | n | n |

|

| ㄷ | / t / | [ti.ɯt̚] | 디읃 | t / d | t | d / t |

|

| ㄹ | / l / | [ɾi.ɯl] | 리을 | r / l | l | r / l |

|

| ㅁ | / m / | [mi.ɯm] | 미음 | m | m | m |

|

| ㅂ | / p / | [pi.ɯp̚] | 비읍 | p / b | p | b / p |

|

| ㅅ | / s / | [si.ɯt̚] | 시읏 | s | s | s |

|

| ㅇ | / ŋ / (/ o /) | [i.ɯŋ] | 이응 | - / ng | - / ng | - / ng |

|

| ㅈ | / ʦ / | [ʦi.ɯt̚] | 지읒 | ch / j / t | c | y / t |

|

| ㅊ | / ʦʰ / | [ʦʰi.ɯt̚] | 치읓 | ch '/ t | ch | ch / t |

|

| ㅋ | / kʰ / | [kʰi.ɯk̚] | 키읔 | k '/ k | kh | k |

|

| ㅌ | / tʰ / | [tʰi.ɯt̚] | 티읕 | t '/ t | th | t |

|

| ㅍ | / pʰ / | [pʰi.ɯp̚] | 피읖 | p '/ p | ph | p |

|

| ㅎ | / h / | [hi.ɯt̚] | 히읗 | H / - | H | H / - |

|

| ㄲ | / k͈ / | [tøːn.ɡi.ɯk̚] | 된 기윽 | kk / k | kk | kk / k | |

| ㄸ | / t͈ / | [tøːn.di.ɯt̚] | 된 디읃 | dd / d | dd | dd / d | |

| ㅃ | / p͈ / | [tøːn.bi.ɯp̚] | 된비읍 | pp / p | pp | pp / p | |

| ㅆ | / s͈ / | [tøːn.si.ɯt̚] | 된 시 읏 | ss / t | ss | ss / t | |

| ㅉ | / ʦ͈ / | [tøːn.ʣi.ɯt̚] | 된지 읒 | cch / t | cc | yy / d | |

These are the order and the names in North Korea. The letter ㅇ is only as / ŋ / performed on the end of a syllable in this order; Words in which it acts as a vowel carrier at the beginning of the syllable are placed under the vowels at the end of the alphabet. In North Korea the letter designations are phonologically completely regular / C i.ɯ C /, where C stands for the respective consonant. Some letters in South Korea have other names that go back to Ch'oe Sejin (see below): ‹k› ㄱ means [ki.jək̚] 기역 , ‹t› ㄷ [ti.ɡɯt̚] 디귿 and ‹s› ㅅ [si.ot̚ ] 시옷 .

The doubled characters used to reproduce the tense consonants were formerly known throughout Korea as "hart" ( [tøːn] 된 ); in North Korea they are still called that, in South Korea they are now called "double" ( [s͈aŋ] 쌍 / 雙 : [s͈aŋ.ɡi.jək̚] 쌍기역 , [s͈aŋ.di.ɡɯt̚] 쌍디귿 etc.).

There are several common alphabetical orders in South Korea, all of which are based on the following scheme:

| ㄱ ( ㄲ ) | ㄴ | ㄷ ( ㄸ ) | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ ( ㅃ ) | ㅅ ( ㅆ ) | ㅇ | ㅈ ( ㅉ ) | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ |

| ‹ K › (‹ k͈ ›) | ‹ N › | ‹ T › (‹ t͈ ›) | ‹ L › | ‹ M › | ‹ P › (‹ p͈ ›) | ‹ S › (‹ s͈ ›) | ‹ Ŋ › / ‹Ø› | ‹ ʦ › (‹ ʦ͈ ›) | ‹ ʦʰ › | ‹ Kʰ › | ‹ Tʰ › | ‹ Pʰ › | ‹ H › |

The character ㅇ is always used in this order, regardless of whether it stands for / ŋ / or only serves as a vowel carrier at the beginning of the syllable. Whether a consonant character is doubled at the beginning of a word or not is ignored in the sorting; in the case of otherwise identical words, the word is followed by the double consonant sign. Double consonant characters and consonant combinations at the end of a word are either ignored or sorted separately, in the following order:

| ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄳ | ㄴ | ㅧ | ㄹ | ㄺ | ㄻ | ㄼ | ㄽ | ㄾ | ㄿ | ㅀ | ㅂ | ㅄ | ㅅ | ㅆ |

| ‹ K › | ‹ K͈ › | ‹ Ks › | ‹ N › | ‹ Ns › | ‹ L › | ‹ Lk › | ‹ Lm › | ‹ Lp › | ‹ Ls › | ‹ Ltʰ › | ‹ Lpʰ › | ‹ Lh › | ‹ P › | ‹ Ps › | ‹ S › | ‹ S͈ › |

Combinations of consonants at the end of a syllable are called "Untergestell" ( [pat̚.ʦʰim] 받침 ), e.g. B. [ɾi.ɯl ki.ɯk̚ pat̚.ʦim] or [ɾi.ɯl ki.jək̚ pat̚.ʦim ] for ‹lk› ㄺ .

Vowels

The vowel letters and combinations of letters have no special names. The vowel length is meaningful in Korean; however, the Korean script does not distinguish between long and short vowels .

| Letter | phoneme | McC-R | Yale | RR | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㅏ | / a / | a | a | a |

|

| ㅑ | / yes / | ya | ya | ya |

|

| ㅓ | / ə / | O | e | eo |

|

| ㅕ | / jə / | yŏ | ye | yeo |

|

| ㅗ | / o / | O | O | O |

|

| ㅛ | / jo / | yo | yo | yo |

|

| ㅜ | / u / | u | wu | u |

|

| ㅠ | / ju / | yu | yu | yu |

|

| ㅡ | / ɯ / | ŭ | u | eu |

|

| ㅣ | / i / | i | i | i |

|

| ㅐ | / ɛ / | ae | ay | ae |

|

| ㅒ | / jɛ / | yae | yay | yae |

|

| ㅔ | / e / | e | ey | e |

|

| ㅖ | / each / | ye | yey | ye |

|

| ㅚ | / ø / | oe | oy | oe | |

| ㅟ | / y / | ue | wi | wi | |

| ㅢ | / ɰi / | ŭi | uy | ui | |

| ㅘ | / wa / | wa | wa | wa | |

| ㅝ | / wə / | Where | we | Where | |

| ㅙ | / wɛ / | wae | way | wae | |

| ㅞ | / we / | we | wey | we |

This is the order of the vowel letters in North Korea. The order in South Korea is as follows:

| ㅏ | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ |

| < A > | ‹ Ɛ › | ‹ Yes › | ‹ Jɛ › | ‹ Ə › | ‹ E › | ‹ Jə › | ‹ Each › | ‹ O › | ‹ Wa › | ‹ Wɛ › | ‹ Ø › | ‹ Yo › | ‹ U › | ‹ Wə › | ‹ We › | ‹ Y › | ‹ Ju › | ‹ Ɯ › | ‹ ɰi › | ‹ I › |

Blocks of syllables

|

Initial: [ʦʰo.səŋ] 초성 / 初 聲 Nucleus: [ʦuŋ.səŋ] 중성 / 中 聲 Final: [ʦoŋ.səŋ] 종성 / 終 聲 |

The individual letters are put together to form more or less square blocks, each corresponding to a syllable. There are three positions in every written syllable: initial, nucleus and final. In the case of syllables that begin with a vowel, the first position is filled with the character ㅇ . The second position is filled with a vowel or diphthong letter. The third position is either filled with a consonant letter or remains empty.

Depending on the shape of the letters, the written syllables are composed differently:

For ‹ i › ㅣ and the vowel signs derived from it, the sign for the initial consonant is on the left. Examples - ‹ ha ›, ‹ hi ›, ‹ he ›:

With ‹ ɯ › ㅡ and the vowel signs derived from it, the sign for the initial consonant is at the top. Examples - ‹ ho ›, ‹ hɯ ›, ‹ hu ›:

In the case of the diphthong signs, which have both a long horizontal and a long vertical line, the sign for the initial consonant is at the top left.

Examples - ‹ hwa ›, ‹ hɰi ›, ‹ hwe ›:

The characters for the final consonant are underneath.

Examples - ‹ hak ›, ‹ hok ›, ‹ hwak ›:

The letters change their shape a little when they are put together so that the syllable roughly fits into a square.

spelling, orthography

Modern spelling is essentially morphophonemic ; That is , every morpheme is always spelled the same, even if the pronunciation varies.

However, some phonologically distinctive features are not distinguished in the script. The length or shortness of vowels is a difference in meaning, but is not expressed in Scripture: The Word / pəːl / 벌 "Bee" for example, is written the same way as the word / pəl / 벌 / 罰 "penalty" . The tense pronunciation of consonants is not always expressed in the scriptures / Kan ɡ a / 강가 / 江가 "Riverside" is the same as written / Kan K a / 강가 / 降嫁 "Marriage under the Stand ".

When the script was created, the letters were essentially arranged into blocks according to the spoken syllables. Later - especially after a suggestion from 1933 - it was no longer written according to spoken syllables, but morphophonemically. Examples:

- [ haːn.ɡu.ɡin ] “(South) koreans” is written ‹ han.ku k .in › 한국인 (instead of ‹ han.ku. k in › 한구 긴 ) because it comes from the morphemes / haːn / + / ku k / "(South) Korea" and / in / "Mensch" exists.

- [ Cape ] "price" is < cape s > 값 written, for example, when the Nominativsuffix / i / should occur, the word [is Ch. s i ] spoken (and written ‹ kap s .i › 값 이 ). The phoneme / s / belongs to the tribe, although it (if the word is used without suffix) is not realized at the end of a word.

- [ ki. pʰ ɯn ] “to be deep” is written ‹ ki pʰ .ɯn › 깊은 (instead of ‹ ki. pʰ ɯn › 기픈 ) because the stem is / ki pʰ / and / ɯn / is a suffix, i. H. that / pʰ / ᄑ belongs to the tribe. The principle applies to all derivatives:

Morphophonemischer sound change is generally not taken into account in Scripture (except - in the South Korean spelling - the allophones of / l / ㄹ , see Section varieties ).

White space and punctuation

Words are separated by spaces, with all suffixes and particles written together with the preceding word. Essentially the same punctuation marks are used as in European languages.

Writing direction

The blocks of syllables were originally written in columns from top to bottom, as in the Chinese script, and the columns were arranged from right to left. From a European perspective, books were therefore read “from behind”. In modern printed matter, however, the direction of writing is from left to right, as in European languages, in lines that are arranged from top to bottom.

Varieties

|

“Cultural language”: [ mun.hwa.ə ] 문화어 / 文化 語 “Standard language”: [ pʰjo.ʣu.nə ] 표준어 / 標準 語 |

There are some differences in spelling between North and South Korea. In the standard variety of North Korea ( "cultural language"), the phoneme is / l / in Sino Korean words and always at the beginning of a syllable and word inside [ ɾ ] spoken and written. In the standard variety South Korea ( "Standard Language") it will often according to certain rules either realized or not [ n ] speaking and in some cases written (the letters) so:

| North Korea | South Korea | Chinese | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| [ ɾ jək̚.s͈a ] ‹ ɾ jək.sa › 력사 |

[ j ək̚.s͈a ] ‹ j ək.sa › 역사 |

歷史 | "History" |

| [ toŋ. ɾ ip̚ ] ‹ tok. ɾ ip › 독립 |

[ toŋ. n ip̚ ] ‹ tok. ɾ ip › 독립 |

獨立 | "Independence" |

| [ ɾ o.doŋ ] ‹ ɾ o.toŋ › 로동 |

[ n o.doŋ ] ‹ n o.toŋ › 노동 |

勞動 | "Job" |

In South Korea this breaks the morphophonetic principle in favor of an approximation of the pronunciation:

| North Korea | South Korea | Chinese | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| [ nj ə.ʣa ] ‹ nj ə.ʦa › 녀자 |

[ j ə.ʣa ] ‹ j ə.ʦa › 여자 |

女子 | "Woman" |

| [ miː. ɾ ɛ ] ‹ mi. ɾ ɛ › 미래 |

[ miː. ɾ ɛ ] ‹ mi. ɾ ɛ › 미래 |

未來 | "Future" |

| [ ɾ ɛː.wəl ] ‹ ɾ ɛ.wəl › 래월 |

[ n ɛː.wəl ] ‹ n ɛ.wəl › 내월 |

來 月 | "next month" |

Other words are also used in North Korea and South Korea e.g. T. each written differently.

Use of Chinese characters

|

Chinese characters: [ haːn.ʦ͈a ] 한자 / 漢字 (Hancha, Hanja) |

At present, a combination of Chinese characters - Korean Hanja - and the Korean alphabet is sometimes used in South Korea ; in North Korea, Chinese characters are practically no longer used.

According to a royal decree of 1894, all government documents were to be written using the Korean alphabet only. However, the decree was hardly followed. At least two newspapers appeared in the Korean alphabet only, but other newspapers used Chinese characters for loanwords from Chinese and the Korean alphabet for all-Korean words, suffixes and particles. This mixed spelling became generally accepted.

In North Korea, the use of Chinese characters in everyday life was abolished in 1949. Later a certain number of Chinese characters were sometimes taught in schools; however, they are practically not used in print products and in everyday life.

The South Korean National Assembly passed a law in 1948 that stipulated the exclusive use of the Korean alphabet. This was followed in the school system, but not in the media and other areas of society. Presidential decrees followed in 1956 and 1957, which also had little success. In 1964, the Ministry of Education mandated that 1,300 common Chinese characters be taught in schools. In 1970 the use of Chinese characters in documents and school books was again banned. From 1972 1,800 Chinese characters were again taught in secondary schools and in 1975 corresponding school books were published. However, newspapers and scientific publications are usually not limited to these 1,800 Chinese characters.

In texts that are otherwise written exclusively with the Korean alphabet, Chinese characters are sometimes used to clarify the etymology or the meaning of proper names and homophones . The name in the passport was given in Latin, Korean and, a few years ago, also in Chinese characters.

history

Older writings

Originally, the only written language in Korea was Classical Chinese .

From the early Koryŏ dynasty , a system called [ hjaŋ.ʦʰal ] 향찰 / 鄕 札 (“native letters”) was used to write purely Korean texts using Chinese characters.

|

[ riː.du ] 리두 / 吏 讀 , 吏 頭 [ riː.do ] 리도 / 吏 道 [ riː.mun ] 리문 / 吏 文 |

Around 692 AD, Minister Sŏlch'ong 薛 聰 is said to have invented or systematized the official script Ridu. This system was mainly used to write proper names, songs and poems as well as notes on Chinese-language texts. Korean words were written either according to the rebus principle with Chinese characters with a similar meaning ( logograms ; see synonymy ) or with Chinese characters with a similar pronunciation ( phonograms ; see homonymy ):

| Korean | Ridu | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| / pəl / "bright" | 明 | according to the meaning of the Chinese character for míng "bright" |

| / pam / "night" | 夜 | according to the meaning of the Chinese character for yè "night" |

In the 13th century, simplified Chinese characters called Gugyeol ([ ku.ɡjəl ] 구결 / 口訣 or to [ tʰo ] 토 / 吐 ) were used to annotate Chinese texts or to reproduce Korean syllables aloud .

New font

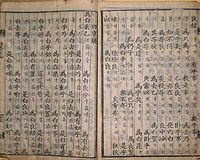

In the middle of the 15th century, King Sejong finally created an alphabet made up of 17 consonant and 11 vowel signs. The script is presented in the work The Right Sounds to Instruct the People ( 訓 民 正音 ), which is attributed to King Sejong himself. At the same time, the commentary appeared explanations and examples of the correct sounds for teaching the people ( 訓 民 正音 解 例 ) by scholars of the Royal Academy of Worthy ( 集賢 殿 ). Both books are written in Chinese.

The first work written in the new alphabet was the songs of the dragons flying into the sky ( 龍飛 御 天歌 ), which celebrates the founding of the Chos Chn dynasty and the predecessors of Sejong:

| 불휘 기픈 남 ᄀ ᆞ ᆫ ᄇ ᆞ ᄅ ᆞ 매 아니 뮐 ᄊ ᆡ | A tree with deep roots is not bent by the wind, |

| 곶 됴코 여름 하 ᄂ ᆞ 니 | flowers profusely and bears fruit. |

| ᄉ ᆡ 미 기픈 므른 ᄀ ᆞ ᄆ ᆞ 래 아니 그츨 ᄊ ᆡ | Water from a deep spring does not dry up in a drought, |

| 내히 이러 바 ᄅ ᆞ 래 가 ᄂ ᆞ 니 | becomes a stream and flows into the sea. |

| (from the songs of the dragons flying into the sky ) | |

The first Buddhist text in the new script was the episodes from the life of the Buddha (釋 譜 詳 節), followed by the melodies of the moon shining on a thousand rivers (月 印 千 江 之 曲) and the pronunciation dictionary The correct rhymes of the land in East (東 國 正 韻) - all three works date from 1447.

In 1449 the first book in the new alphabet was printed with metal letters . However, it is not preserved.

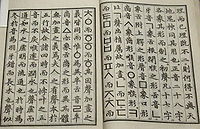

In 1527 Ch'oe Sejin 崔世珍 (1478? –1543) rearranged the letters in his Chinese textbook Hunmong Chahoe 訓 蒙 字 會 and gave some consonants names, the first syllable of which begins with the corresponding sound and the second syllable of corresponding sound ends:

- ㄱ ‹ k › 其 役 / ki.jək /

- ㄴ ‹ n › 尼 隱 / ni.ɯn /

- ㄷ ‹ t › 池 末 / ti.kɯt /

- ㄹ ‹ l › 梨 乙 / li.ɯl /

- ㅁ ‹ m › 眉 音 / mi.ɯm /

- ㅂ ‹ p › 非 邑 / pi.ɯp /

- ㅅ ‹ s › 時 衣 / si.əs /

- ㆁ ‹ ŋ › 異 凝 / ŋi.ɯŋ /

modernization

The vowel letter ㆍ ‹ ɐ ›, the three consonant letters ㅿ ‹ z ›, ㆆ ‹ ʔ › and ㆁ ‹ ŋ › (also at the beginning of the syllable; coincided with ㅇ ), the combinations ㅸ , ㅹ , ㆄ , ㅱ , ㆅ , ᅇ and the numerous Consonant clusters at the beginning of the syllable were later abolished because the corresponding sounds or sound sequences no longer exist in modern Korean. For which sounds these signs originally stood is a matter of dispute; some were only used for Chinese or Sinocorean words. For Chinese words there were originally modified versions of the letters ㅅ < s >, ㅆ < S >, ㅈ < ʦ >, ㅉ < ʦ͈ > and ㅊ < ʦʰ > (namely ᄼ , ᄽ , ᅎ , ᅏ and ᅔ and ᄾ , ᄿ , ᅐ , ᅑ and ᅕ ) as well as many combinations of vowel signs that are no longer used today.

Fifteenth-century Korean was a tonal language and the tones were originally marked in the script by dots to the left of the block of syllables. These tone symbols were later also abolished, although the corresponding phonemes are also partly reflected in modern Korean (as vowel length).

Prohibition

Shortly after Korea was incorporated into the Japanese Empire in 1910, Japanese was introduced as the sole national language. With the exception of a few newspapers, the use of the Korean language and script was banned and superseded by Japanese, and from 1942 to 1945 it was no longer taught in schools.

present

Between 2009 and 2012 there were efforts to establish Hangul for the Cia-Cia language in Sulawesi , but this was abandoned in favor of a Latin version of the language.

Letter shapes

According to the traditional representation, the graphically simplest consonant signs are simplified illustrations of the speech tools when pronouncing the corresponding sounds. According to research by Gari L. Ledyard, the characters for the phonetically simplest consonants are derived from the 'Phagspa script .

Legends

There are numerous legends about writing and how it came about. Legend has it that it was inspired by the latticework on traditional Korean doors; According to another legend of the patterns that silkworms eat in mulberry leaves.

tradition

The three original basic vowel signs are supposed to represent heaven ( ㆍ ‹ ɐ ›), earth ( ㅡ ‹ ɯ ›) and humans ( ㅣ ‹ i ›) according to cosmological ideas . All other vowels and diphthongs are derived from them. The dot later became a short line in these combinations. Only the combinations still used today are listed below:

- ㅣ < i > → ㅏ < a > → ㅑ < yes >

- ㅣ ‹ i › → ㅓ ‹ ə › → ㅕ ‹ jə ›

- ㅡ ‹ ɯ › → ㅗ ‹ o › → ㅛ ‹ jo ›

- ㅡ ‹ ɯ › → ㅜ ‹ u › → ㅠ ‹ ju ›

Further derivatives, followed by ㅣ ‹ i ›:

- ㅏ < a > → ㅐ < ɛ >

- ㅑ < yes > → ㅒ < jɛ >

- ㅓ ‹ ə › → ㅔ ‹ e ›

- ㅕ ‹ jə › → ㅖ ‹ je ›

- ㅡ ‹ ɯ › → ㅢ ‹ ɰi ›

- ㅗ ‹ o › → ㅚ ‹ ø ›

- ㅜ ‹ u › → ㅟ ‹ y ›

Further derivatives, preceded by ㅗ ‹ o ›:

Further derivatives, preceded by ㅜ ‹ u ›:

The graphically simplest five consonant signs are intended to represent the position of the speech tools when pronouncing the corresponding sounds:

- ㄱ ‹ k › is supposed to represent the root of the tongue blocking the throat (seen from the left).

- ㄴ ‹ n › is intended to represent the tip of the tongue that touches the alveoli (seen from the left).

- ㅁ ‹ m › is supposed to represent the lips .

- ㅅ ‹ s › is supposed to represent the incisors .

- ㅇ ‹ Ø › is intended to represent a cross section through the neck .

According to this idea, the two letters ㄱ ‹ k › and ㄴ ‹ n › are simplified representations of how the corresponding consonants were pronounced, and the other three letters ㅁ ‹ m ›, ㅅ ‹ s › and ㅇ ‹ Ø › simplified representations of the speech organs involved . The remaining consonant signs are derived from these letters:

- ㄱ ‹ k › → ㅋ ‹ kʰ ›

- ㄴ ‹ n › → ㄷ ‹ t › → ㅌ ‹ tʰ ›

- ㅅ ‹ s › → ㅈ ‹ ʦ › → ㅊ ‹ ʦʰ ›

- ㅇ ‹ Ø › → ㆆ ‹ ʔ › → ㅎ ‹ h ›

This would be the first and only time that articulatory features have been incorporated into the design of a font. However, this assumption is controversial.

'Phagspa

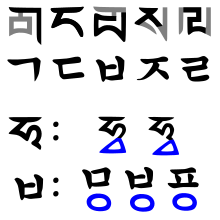

Bottom lines: In the 'Phagspa script, the characters for w, v and f are derived from the letter h with w underneath ; the Korean equivalents are formed by the letter p and its derivatives with a circle below it.

The Korean alphabet was not created in an intellectual vacuum . King Sejong was well versed in traditional Chinese phonology and studied the scriptures of neighboring countries in Korea.

According to Gari K. Ledyard and other linguists , at least the phonetically simplest five characters ( ㄱ ‹ k ›, ㄷ ‹ t ›, ㄹ ‹ l ›, ㅂ ‹ p › and ㅈ ‹ ʦ ›) are from the corresponding characters of the ' Phagspa script (ꡂ ‹ g ›, ꡊ ‹ d ›, ꡙ ‹ l ›, ꡎ ‹ b › and ꡛ ‹ s ›), which in turn refer to the Tibetan script (ག ‹ ɡ ›, ད ‹ d ›, ལ ‹ l ›, བ ‹ b › and ས ‹ s ›) goes back.

According to this theory, the Korean script could ultimately be traced back to the same Semitic origin as the scripts of India , Europe and Southeast Asia as well as Hebrew and Arabic ; four of the five letters mentioned would therefore be related to their Greek (Γ, Δ, Λ, Β) and Latin equivalents (C, D, L, B).

pressure

Modern printing companies used letters for blocks of syllables, not for individual letters. Up to 2500 letters were therefore required for the sentence.

computer

In the data processing on computers usually are not individual letters, but each considered whole syllable combinations as units and encoded. Since there are thousands of possible syllables, the input is made letter by letter via the keyboard and special software converts the letter-by-letter input into a syllable-by-syllable coding and representation.

Unicode

All 11,172 possible syllable combinations that are used to write modern Korean were encoded syllable for syllable in Unicode . The Korean script is divided into four areas in Unicode: whole syllables (“ Hangul Syllables ”, U + AC00 to U + D7A3); Initial consonants, vowel nuclei and final consonants (“ Hangul Jamo ”, U + 1100 to U + 11FF); modern and no longer used letters for backward compatibility with EUC-KR (“ Hangul Compatibility Jamo ”, U + 3131 to U + 318E); and half-width letters (parts of “ Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms ”, U + FFA0 to U + FFDC).

input

There are several Korean keyboard layouts . The most common keyboard layout in South Korea is called [ tuː.bəl.sik̚ ] 두벌식 (Transliteration: Dubeolsik ). With this assignment, the consonant signs are struck with the left hand and the vowel signs with the right hand.

transcription

Until recently, the two most common systems for transcribing Korean into Latin script were the McCune-Reischauer transcription and the Yale transcription . The Yale transcription is mainly used in linguistic works and z. Sometimes used in textbooks, the McCune-Reischauer system in all other scientific publications.

The Yale transcription essentially follows the spelling with Korean letters; the phonemes / n / and / l / at the beginning of the syllable in Sino-Korean words, which in South Korea z. T. are not pronounced, are denoted with the superscript letters n and l and the phoneme at the end of the syllable, which causes a strained pronunciation of the following consonant in compounds, is transcribed as q. Long vowels are identified by a length sign (horizontal line above the vowel letter).

The McCune-Reischauer transcription is more closely based on the phonetic realization.

Neither the Yale nor the McCune-Reischauer transcription can be derived directly from the Korean script without knowledge of the language.

In 1984 the South Korean Ministry of Culture and Tourism issued a new transcription system which is essentially based on the McCune-Reischauer transcription (" revised Romanization ").

See also

- Unicode block of Hangeul syllable characters

- Hangeul Day , Korean Alphabet Remembrance Day

- Korean schools in Germany

literature

- Young-Key Kim-Renaud (Ed.): The Korean alphabet. Its history and structure . University of Hawaii Press, 1997.

- Gari Keith Ledyard: The Korean Language Reform of 1446. The Origin, Background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet . University of California Press, 1966. (Reprinted by Singu Munhwasa, 1998)

- S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2-30.

- Kim Sang-tae, Kim Hee-soo, Kim Mi-mi, Choi Hyun-se (eds.): History of Hangeul . Seoul, National Hangeul Museum , 2015.

Web links

- Korean in Omniglot (English)

- Digital Hangeul Museum (Korean and English)

- Korean virtual keyboard. Write Korean characters online (English); accessed March 1, 2014.

References and comments

- ↑ Iksop Lee, S. Robert Ramsey: The Korean Language . SUNY Press, 2000, ISBN 0-7914-4832-0 , p. 75

- ^ Tale of Hong Gildong . World Digital Library. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ↑ The Great Brockhaus in twelve volumes . FA Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 16 1979, vol. 6, p. 454.

-

↑ A broad transcription is used according to the following scheme:

Bilabial Alveolar Post-alveolar Velar Palatal Glottal nasal / m / / n / / ŋ / Plosives

und

easy / p / ( [ p ] ~ [ b ] ) / t / ( [ t ] ~ [ d ] ) / ʦ / ( [ ʦ ] ~ [ ʣ ] ) / k / ( [ k ] ~ [ ɡ ] ) curious; excited / p͈ / / t͈ / / ʦ͈ / / k͈ / aspirated / pʰ / / tʰ / / ʦʰ / / kʰ / Fricatives easy / s / / h / curious; excited / s͈ / Liquid / l / ( [ l ] ~ [ ɾ ] ) Approximant / w / / ɰ / / j / The pronunciation of / ʦ / is between [ʦ] and [ʧ], that of the corresponding voiced allophone between [ʣ] and [ʤ] etc .; / s / is before / a / , / ə / , / o / , / u / , / ɯ / , / ɛ / , / e / and / ø / z. T. easily aspirated as [ S ] spoken before / i / and / y / weak palatalised against [ ɕ ] (Wilfried Herrmann, Chŏng Chido: Textbook of modern Korean language . Buske, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-87548-063-5 , p. 10). Transcription of the vowels and diphthongs :

front central back ung. ger. ung. ger. ung. ger. closed / i / ㅣ

/ ɰi / ㅢ

/ y / ㅟ

/ ɯ / ㅡ / u / ㅜ

/ ju / ㅠ

half closed / e / ㅔ

/ ø / ㅚ

/ o / ㅗ

/ jo / ㅛ

medium / ə / ㅓ

half open / ɛ / ㅐ

open / a / ㅏ

- ↑ For example in numerous publications by 한글 학회 , 한길사 and 나라말 .

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 129; S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2–30, here p. 26 f.

- ^ A b Samuel E. Martin: Reference Grammar of Korean. A Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language . Tuttle Publishing, 2006, p. 21 f.

- ^ Samuel E. Martin: Reference Grammar of Korean. A Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language . Tuttle Publishing, 2006, p. 7 f .; Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 142 f.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 144.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 79.

- ↑ Ho-Min Sohn: Orthographic Divergence in South and North Korea: Toward a Unified Spelling System . In: Young-Key Kim-Renaud (Ed.): The Korean alphabet. Its history and structure . University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pp. 193-217; Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 146 ff.

- ↑ Florian Coulmas: The writing systems of the world . Wiley-Blackwell, 1991, pp. 122, 242 f.

- ↑ a b c d Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 145.

- ↑ a b Ho-min Sohn: The Korean Language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 77.

- ↑ Christa Dürscheid : Introduction to Script Linguistics . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, p. 89; Insup Taylor, Maurice M. Taylor: Writing and literacy in Chinese, Korean and Japanese . John Benjamin, Amsterdam 1995, pp. 223, 245.

- ↑ The Great Brockhaus in twelve volumes . FA Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 16 1979, Vol. 6, p. 454; Iksop Lee, S. Robert Ramsey: The Korean Language . State University of New York Press, 2000, p. 48 ff.

- ↑ Modern reading and writing styles in South Korea: Idu 이두 , Ido 이도 , Imun 이문 .

- ↑ The Great Brockhaus in twelve volumes . FA Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 16 1979, Vol. 6, p. 454; Florian Coulmas: The writing systems of the world . Wiley-Blackwell, 1991, p. 116 f .; Florian Coulmas: The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems . Wiley-Blackwell, 1999, p. 225; Seung-Bog Cho: On Idu. In: Rocznik Orientalistyczny 46: 2 (1990), pp. 23-32.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 124.

- ↑ Ho-min son: Korean . Taylor & Francis, 1994, p. 5.

- ↑ Punghyun Nam: On the Relations Between 'Hyangchal' and 'Kwukyel' . In: Young-Key Kim-Renaud (Ed.): Theoretical Issues in Korean Linguistics . Center for the Study of Language and Information, 1994, 419-423; Insup Taylor, Martin M. Taylor: Writing and literacy in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese . John Benjamin, 1995, p. 106; Florian Coulmas: The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems . Wiley-Blackwell, 1999, pp. 273, 280; Iksop Lee, S. Robert Ramsey: The Korean Language . State University of New York Press, 2000, pp. 51 f .; 구결 학회 www.ikugyol.or.kr .

- ↑ a b c Hánguó guólì guóyǔyuàn 韩国国立 国语 院 (ed.), Hán Méi 韩梅 ( transl .): Xùn mín zhèng yīn « 训 民 正音 ». Shìjiè túshū chūbǎn gōngsī 世界 图书 出版 公司 , Beijing 2008.

- ↑ The Great Brockhaus in twelve volumes . FA Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 16 1979, vol. 6, p. 454.

- ↑ The modern Korean spelling of the title is ‹ hun min ʦəŋ ɯm › 훈민정음 , but the title was originally written ‹ • hun min • ʦjəŋ ʔɯm › • 훈민 • 져 ᇰ ᅙ ᅳ ᆷ (see illustration). Many computer systems currently in use, however, do not correctly combine the individual Korean letters into syllables.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 129.

- ↑ a b Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 136.

- ↑ a b Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 138.

- ↑ With the Korean word for “end”, / kɯt / 귿 (from which the modern word [ kɯt ] 끝 comes from ), instead of the Sinocorean reading / mal / 말 for 末 .

- ↑ The Korean word for "clothes" / əs / 엇 , the Sino Korean reading / instead ɰi / 의 for 衣 , because there is no Sino Korean word on / s / ends.

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2-30, here p. 25; Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Sejong Institute withdrawal to leave Cia-Cia out in cold. In: koreatimes.co.kr. Retrieved May 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Adoption of Hangeul by Indonesian Tribe Hits Snag - The Chosun Ilbo (English Edition): Daily News from Korea - national / politics> national. In: english.chosun.com. Retrieved May 26, 2019 .

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2–30, here p. 25.

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2-30, here p. 24; Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 13.

- ^ Gari Ledyard: The International Linguistic Background of the Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People . In: Young-Key Kim-Renaud (Ed.): The Korean alphabet. Its history and structure . University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pp. 31-87, here p. 40; S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2-30, here p. 23; Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 13.

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2–30, here p. 23.

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2–30, here p. 24.

- ↑ Florian Coulmas: Writing systems . Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 157.

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2-30, here p. 25; see. Gari Ledyard: The International Linguistic Background of the Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People . In: Young-Key Kim-Renaud (Ed.): The Korean alphabet. Its history and structure . University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pp. 31-87.

- ↑ Including Yi Ik, Yu Hi and Yi Nung-hwa; see. Lee Sangbaek: The origin of Korean alphabet (sic) “Hangul” . Ministry of Culture and Information, Republic of Korea, 1970, p. 9.

- ^ Gari Ledyard: The International Linguistic Background of the Correct Sounds for the Instruction of the People . In: Young-Key Kim-Renaud (Ed.): The Korean alphabet. Its history and structure . University of Hawaii Press, 1997, pp. 31-87, here pp. 43 ff.

- ^ S. Robert Ramsey: The Invention and Use of the Korean Alphabet . In: Ho-min Sohn (Ed.): Korean language in culture and society . University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp. 2-30, here p. 29; Jeon Sang-woon: Printing Technology . In: A History of Science in Korea (Korean Studies Series 11). Jimoondang, 1998.

- ↑ How to type Korean / Hangul on your computer (Windows Vista) . Video on Youtube. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ Ho-min son: The Korean language . Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 149.

- ^ Samuel E. Martin: Reference Grammar of Korean. A Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language . Tuttle Publishing, 2006, p. 9 ff.