Essedum

The Essedum is the Latin name for a chariot , as it was used by the Celts in armed conflicts. The corresponding Celtic word is essedon. It was a two-wheeled chariot drawn by two horses, each manned by a fighter and a handlebar.

Since every Celtic warrior had to pay for the weapons himself, the two-wheeled chariot was also reserved for an upper social class, while the majority of the fighters formed the foot troops. The burial with a chariot or with parts of the same thus underscored the social rank of the deceased.

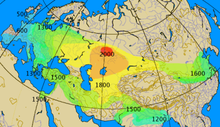

The Celtic Esseda were the last chariots used in battles. On the European mainland they were made between 700 and 100 BC. Used in Britain and Ireland until 200 AD.

development

The Celtic chariot originally comes from the Orient , the earliest users could have been the Mitanni . It was used by the Greeks and Romans as a racing and triumphal car (Latin biga ) and occasionally as a touring car (in a modified form with a driver's seat ). The word essedum contains the Latin 'en' = in and 'sedere' = to sit. In comparison to the carrus (lat. = Four-wheeled cart, cart) it is primarily a combat device.

In the Hallstatt period , the four-wheeled car was predominant, which, because of its difficult and clumsy handling, served more as a cult car and as a show car for representation. In the princely burial place of Vix and the hill grave near Eberdingen-Hochdorf it is archaeologically tangible. In the Latène period , the two-wheeled chariot was primarily used in the now increasing armed conflicts both with their own related tribes and with neighboring foreign peoples.

The Romans first made it in 295 BC. At the Battle of Sentinum Acquaintance with this Celtic military equipment. With rattling chariots and carts, the Celts, allied with the Samnites, Etruscans, Umbrians, etc., made a threatening breach in the Roman ranks, because the horses of the Romans shied and passed because of the unusual noise. Quintus Fabius was able to turn the battle fate in favor of the Romans, after first the Samnites and then the Gauls were defeated from the flanks.

The chariot was also used in the battle of Telamon on the Etruscan coast north of Cosa in 225 BC. Used. The Gallic Boier and Insubrian were defeated by the Romans after initial successes.

Description and use

The Sicilian Diodorus , who lived in the last century BC and was a contemporary of Caesar , gives a description of the two-wheeled carriage drawn by two horses . According to his account, the Celts still used it mainly when traveling, because at that time the chariot was no longer in use in battles on the mainland. He was driven by a driver and a fighter, and when they intervened in combat they first threw spears, then the fighter dismounted and fought on foot with a sword. Caesar undertook in 55 BC His first expedition to Britain , where he made his own experience with the Gallic chariot, as it was no longer used in combat on the mainland. Caesar vividly describes the effect and mode of combat of this weapon of war. The loud roar of the wheels alone causes initial confusion. Then the charioteers drive in all directions across the battlefield and hurl their projectiles. Then the warrior jumps to the ground and continues to fight on foot, while the charioteer drives a little out of the battle and positions himself so that he can return from there at any time to pick up the fighter and get him out of the danger zone. In this way the charioteer can also bring replacements into battle. The drivers are so skilled that they can maneuver the car even on sloping terrain. Caesar also reports that the crews could, if necessary, run back and forth over the drawbar to the yoke.

Images on Gallic and Roman coins from that period and images on grave steles in Padua confirm the depictions of Diodorus and Caesar. The side delimitation of the car body is interesting: semicircular, arched, with both a single and double hoop they offer support for the crew, and on the coin of the Remer the two arches are again braced in a Y-shape. The car body is open to the front and back .

Locations

In total, about 200 Celtic chariot graves are known to archaeologists. The most important site is on the northeastern bank of Lake Neuchâtel with the La Tène settlement . In addition to extensive (approx. 2500) other finds, wagon parts, harness and yokes from the 3rd and 2nd centuries were also found, which led to the delimitation of Hallstatt from the name La Tène .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Titus Livius : From Urbe Condita - Liber X-28 ("essedis carrisque") [1]

- ↑ Polybios : Historien - 2.29

- ↑ Diodor : Libraries - 5.29

- ^ Gaius Iulius Caesar : De Bello Gallico - 4, 33