Sintashta culture

| Prehistoric cultures of Russia | |

| Mesolithic | |

| Kunda culture | 7400-6000 BC Chr. |

| Neolithic | |

| Bug Dniester culture | 6500-5000 BC Chr. |

| Dnepr-Don culture | 5000-4000 BC Chr. |

| Sredny Stog culture | 4500-3500 BC Chr. |

| Ekaterininka culture | 4300-3700 BC Chr. |

| Fatyanovo culture | around 2500 BC Chr. |

| Copper Age | |

| North Caspian culture | |

| Spa culture | 5000-3000 BC Chr. |

| Samara culture | around 5000 BC Chr. |

| Chwalynsk culture | 5000-4500 BC Chr. |

| Botai culture | 3700-3100 BC Chr. |

| Yamnaya culture | 3600-2300 BC Chr. |

| Afanassjewo culture | 3500-2500 BC Chr. |

| Usatovo culture | 3300-3200 BC Chr. |

| Glaskovo culture | 3200-2400 BC Chr. |

| Bronze age | |

| Poltavka culture | 2700-2100 BC Chr. |

| Potapovka culture | 2500-2000 BC Chr. |

| Catacomb tomb culture | 2500-2000 BC Chr. |

| Abashevo culture | 2500-1800 BC Chr. |

| Sintashta culture | 2100-1800 BC Chr. |

| Okunew culture | around 2000 BC Chr. |

| Samus culture | around 2000 BC Chr. |

| Andronovo culture | 2000-1200 BC Chr. |

| Susgun culture | around 1700 BC Chr. |

| Srubna culture | 1600-1200 BC Chr. |

| Colchis culture | 1700-600 BC Chr. |

| Begasy Dandybai culture | around 1300 BC Chr. |

| Karassuk culture | around 1200 BC Chr. |

| Ust-mil culture | around 1200–500 BC Chr. |

| Koban culture | 1200-400 BC Chr. |

| Irmen culture | 1200-400 BC Chr. |

| Late corporate culture | around 1000 BC Chr. |

| Plate burial culture | around 1300–300 BC Chr. |

| Aldy Bel culture | 900-700 BC Chr. |

| Iron age | |

| Baitowo culture | |

| Tagar culture | 900-300 BC Chr. |

| Nosilowo group | 900-600 BC Chr. |

| Ananino culture | 800-300 BC Chr. |

| Tasmola culture | 700-300 BC Chr. |

| Gorokhovo culture | 600-200 BC Chr. |

| Sagly bashi culture | 500-300 BC Chr. |

| Jessik Beschsatyr culture | 500-300 BC Chr. |

| Pazyryk level | 500-300 BC Chr. |

| Sargat culture | 500 BC Chr. – 400 AD |

| Kulaika culture | 400 BC Chr. – 400 AD |

| Tes level | 300 BC Chr. – 100 AD |

| Shurmak culture | 200 BC Chr. – 200 AD |

| Tashtyk culture | 100–600 AD |

| Chernyakhov culture | AD 200–500 |

The Sintashta culture (English Sintashta culture , scientifically Sintašta culture ) is an archaeological culture of the Bronze Age , which according to radiocarbon dates from Kuz'mina (2007) to 2800–1650 BC. BC, according to Anthony (2007) narrower to 2100–1800 BC. Is dated. It is partially combined with simultaneous groups for the Sintaschta-Petrowka culture or the Sintaschta-Arkaim culture .

The earliest chariots were found in the graves of the eponymous site of Sintaschta . The Sintashta people engaged in intensive copper mining and significant bronze production. The Sintashta culture was traditionally viewed as the early phase of the Andronovo culture .

origin

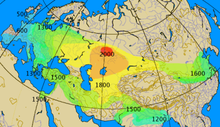

The Sintashta culture developed from the interaction of two previous cultures. Its immediate predecessor in the Ural - Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture , an offshoot of the cattle breeding pit grave or Yamnaja culture , whose members between 2800 and 2600 BC. Immigrated to this region. Some Sintashta cities were built over old Poltawka settlements or near Poltawka burial grounds. Motifs from Poltawka ceramics can be found on Sintashta ceramics. The material culture of the Sintaschta also shows influences of the late Abashevo culture .

The first Sintashta settlements appear around 2100 BC. The swampy plains around the Urals and on the upper Tobol, which were previously used as winter retreats, now became more and more important for survival. Under this pressure, the Poltawka and Abaschewo began to settle permanently in fortified structures in the river valleys, although they avoided the hilltops that were more easily defended. The Abashevo culture was characterized by warfare between the various tribes, which was intensified by the struggle for scarce resources. This led to the construction of numerous fortifications as well as the development of the chariot. The disputes between the tribal groups are reflected in the high number of injuries in the Sintashta tombs.

Metal fabrication

The Sintashta economy is based primarily on copper metallurgy. Copper ores from the nearby mines, such as Vorovskaya Yama , were brought to the Sintashta settlements and processed into copper and arsenic bronze . Remains of smelting furnaces and slag were found in excavated buildings at the sites in Sintaschta, Arkaim and Ust'e. Much of the metal was destined for export to the cities of the oasis culture of Central Asia. This metal trade linked the steppe region for the first time with the ancient urban civilizations of the Middle East: the empires and city-states of Iran and Mesopotamia were important markets for metal. Horses and chariots, ultimately probably Indo-Iranian-speaking people from the steppe to the Middle East, probably came through these trade routes.

Ethnic and Linguistic Identity

The people of the Sintashta culture may speak Proto -Indo-Iranian . This assumption is primarily based on similarities between sections of the Rig Veda , a religious Indian text containing ancient Indo-Iranian hymns transmitted in Vedic Sanskrit , and the funerary culture of the Sintashta as discovered by archaeologists.

Due to their origins from tribes who emigrated from the Urals, it might also be too brief to describe the bearers of the Sintashta culture as an exclusively Indo-Iranian ethnic group, and apparently other Indo-European-speaking groups were also involved in their formation. Early Indo-Iranian loanwords in Ural also suggest that Finno-Ugric tribes have been around since around 3000 BC. Were neighboring.

literature

- David W. Anthony: The Horse, the Wheel and Language. How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the modern World. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ et al. 2007, ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0 .

- David W. Anthony: The Sintashta Genesis: The Roles of Climate Change, Warfare, and Long-Distance Trade. In: Bryan K. Hanks, Katheryn M. Linduff (Eds.): Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia. Monuments, Metals and Mobility. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-51712-6 , pp. 47-73, doi : 10.1017 / CBO9780511605376.005 .

- Bryan K. Hanks: Late Prehistoric Mining, Metallurgy, and Social Organization in North Central Eurasia. In: Bryan K. Hanks, Katheryn M. Linduff (Eds.): Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia. Monuments, Metals and Mobility. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-51712-6 , pp. 146-167, doi : 10.1017 / CBO9780511605376.010 .

- Bryan K. Hanks, Katheryn M. Linduff (Eds.): Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia. Monuments, Metals and Mobility. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-51712-6 .

- Ludmila Koryakova: Sintashta-Arkaim Culture . The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). 1998. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- Ludmila Koryakova: An Overview of the Andronovo Culture: Late Bronze Age Indo-Iranians in Central Asia . The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). 1998. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- PF Kuznetsov: The emergence of Bronze Age chariots in eastern Europe. In: Antiquity. Vol. 80, No. 309, 2006, ISSN 0003-598X , pp. 638-645

- Elena E. Kuz'mina: The Origin of the Indo-Iranians (= Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series , Vol. 3). Brill, Leiden et al. 2007, ISBN 978-900-416-054-5 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The dates in the table are taken from the individual articles and do not always have to be reliable. Cultures in areas of other former Soviet republics were included.

- ↑ EE Kuz'mina (2007), Appendix two.

- ↑ Anthony: The Sintashta Genesis. 2009, p. 374 f.

- ↑ Koryakova: An Overview of the Andronovo Culture. 1998.

- ↑ Koryakova: Sintashta-Arkaim Culture. 1998.

- ^ Kuznetsov: The emergence of Bronze Age chariots in eastern Europe. In: Antiquity. Vol. 80, No. 309, 2006, pp. 638-645.

- ↑ Hanks, Linduff (Ed.): Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia. Monuments, Metals and Mobility. 2009.

- ^ A b Anthony: The Horse, the Wheel and Language. 2007, pp. 390-391.

- ^ Anthony: The Horse, the Wheel and Language. 2007, p. 383 f.

- ^ Anthony: The Horse, the Wheel and Language. 2007, p. 391.

- ^ Anthony: The Horse, the Wheel and Language. 2007, pp. 435-418.

- ^ Anthony: The Horse, the Wheel and Language. 2007, pp. 408-411.

- ↑ Kuz'mina: The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. 2007, p. 222.

-

↑ Häkkinen, Jaakko (2012): Uralic evidence for the Indo-European homeland .

Häkkinen, Jaakko (2012): Early contacts between Uralic and Yukaghir .